name: A Philosophical History of Freedom goal: Discover the evolution of freedom through the ages, from ancient philosophers to modern challenges. objectives:

- Analyze the political philosophies of freedom and power.

- Trace the historical origins of freedom from Antiquity to the Middle Ages.

- Examine the rise and decline of freedom from the 19th to the 20th century.

A Journey Through the Philosophical History of Freedom

A Philosophical History of Freedom explores freedom throughout history. Damien Theillier examines two political philosophies: freedom and power. He analyzes thinkers such as Frédéric Bastiat, Lord Acton, Karl Marx, and Murray Rothbard, shedding light on their views on production, plunder, class struggle, and the State.

The course goes back to the origins of freedom in Antiquity, with the Greeks and Romans, through the Middle Ages, where human freedom is discussed in religious and political contexts. It shows how ideas of freedom evolved with the birth of universities and the first forms of capitalism in Italian cities.

From the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, the course examines the rise of freedom, marked by religious tolerance and economic freedom, culminating in 1776 with major events like the Philadelphia Congress. The 19th and 20th centuries witness the peak and decline of freedom, facing criticisms of capitalism and the dangers of collectivism, putting into perspective the contemporary challenges for freedom.

Introduction

Course Overview

Welcome to PHI201!

This course invites you to explore the evolution of freedom throughout history by analyzing the major schools of thought that have shaped it. You will discover how the concept of freedom has been constructed over the centuries, either in opposition to or collaboration with power, through a historical journey from Antiquity to contemporary debates.

Section 1: Freedom or Power

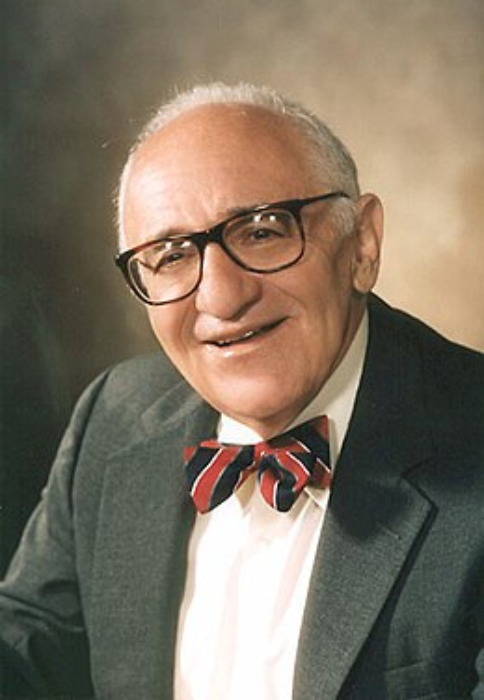

We will begin with an overview of the two major political philosophies that have

marked history: freedom and power. This section will examine the visions of thinkers

such as Frédéric Bastiat on production versus spoliation, Lord Acton who sees

freedom as the driving force of history, Karl Marx with his theory of class struggle,

and Murray Rothbard who opposes the state to society. This conceptual introduction

will provide a framework of analysis for the historical periods.

Section 2: The Origins of Freedom: Antiquity

Here, we will return to the roots of philosophical thought with the Greeks, who

invented critical rationality, and the Romans, who laid the foundations of modern

law. We will also examine the fall of Rome as a pivotal moment that redefined

political and social organization around the notion of freedom.

Section 3: The Origins of Freedom: The Middle Ages

The Middle Ages are often seen as a dark period, but we will discover that it

actually laid the foundations of modern freedom. We will study the assertion

of human freedom, the debates between reason and faith, the birth of the sovereign

state, the biblical ethics valuing the individual, and the first outlines of

capitalism that appear at this time.

Section 4: The Rise of Freedom: From the Renaissance to the Enlightenment

This section will focus on the emergence of religious tolerance and economic

freedom, which gained momentum during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment.

We will also analyze the importance of the year 1776, which marked a major turning

point with key events for the free world, before diving into the era of revolutions

that redefined the very notion of freedom.

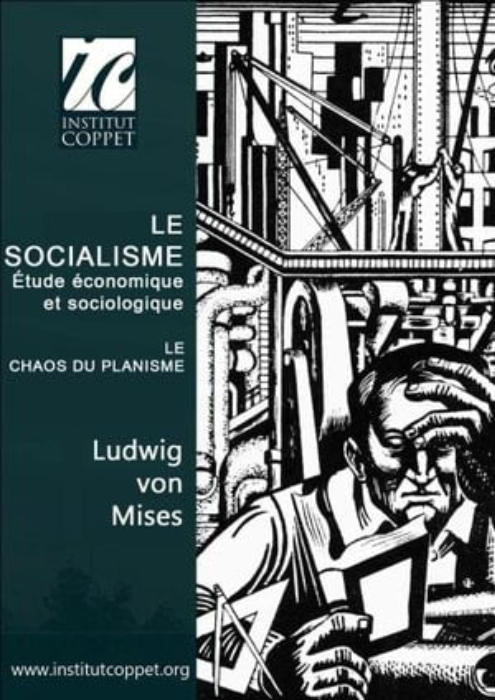

Section 5: Apex and Decline: From the 19th to the 20th Century

We will continue by studying the upheavals of the 19th and 20th centuries, highlighting

the strengths and weaknesses of democracy, Marxist critiques of capitalism, and

the Austrian response to these criticisms. We will also explore warnings about

the dangers of collectivism through major works such as "The Road to Serfdom".

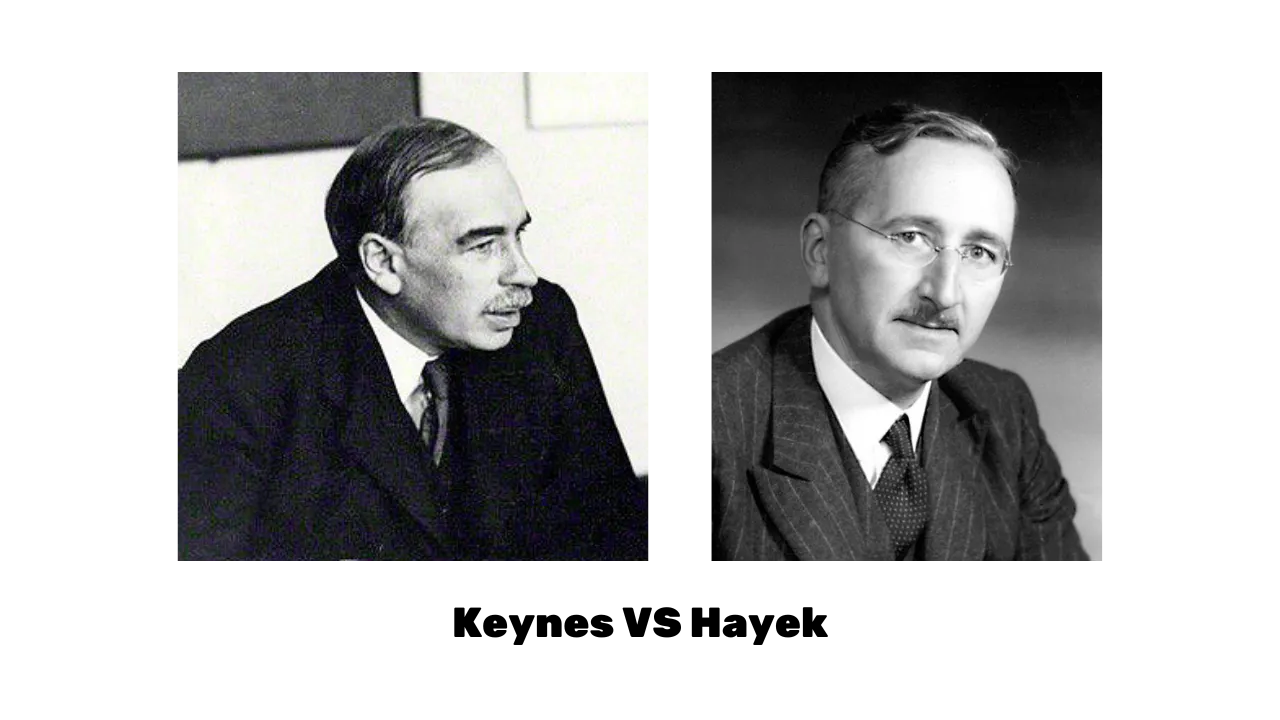

Section 6: The Rise of the Welfare State in the 20th Century

Finally, this section will examine how the welfare state gradually took precedence

over the ideas of economic freedom, notably through the triumph of Keynes and

the abandonment of the gold standard. We will conclude by emphasizing the importance

of ideas in shaping the course of history and the role freedom still plays in

our modern societies.

Ready to embark on this unique philosophical journey on the quest for freedom? Let's go!

Freedom or Power

There are only two political philosophies

Why title this course: a history of freedom? Because we need to understand the relationship between ideas and events, to better judge our era and act with discernment. It is in the past that we find the elements for a better understanding of what freedom is and the reasons why we must cherish it.

When the past no longer illuminates the future, the spirit walks in darkness (Alexis de Tocqueville - Democracy in America.)

At the same time, Auguste Comte said: "One does not fully know a science

until one knows its history." This truth could be applied to the idea of

freedom. Indeed, freedom is not a new idea. It is a legacy passed down

through generations. The entire history of civilization bears witness to a

relentless struggle for freedom.

However, the goal of this course is not only to shed light on the history of freedom but also, and more importantly, to develop critical judgment. Indeed, history alone is not enough to judge the present and the future. It needs to be accompanied by critical reflection and a judgment on the mistakes of the past. This is the contribution of philosophy. That is why I have titled this course: a philosophical history of freedom. It is indeed about exploring how philosophers have conceived of freedom throughout the ages.

The task of philosophy

From its origins, it has a dual purpose:

- Firstly, it is to give meaning to vague and confused concepts. What is good, true, just, beautiful? Just as history's function is to illuminate the past, so philosophy is the art of correctly defining concepts. That is why we need to start in this course by understanding what freedom is.

Freedom is a concept that covers a multitude of variants, which are as many possible declinations of the same reality: political freedom, economic freedom, freedom of conscience, of speech, religious freedom, freedom of association, etc. What reality are we talking about?

Freedom can be simply defined as the power of choice, with what belongs to oneself. It is an inherent faculty of the human being. It is a reality that is essentially individual. Only the individual can think and act, that is, make choices. This does not mean that the individual is alone, that he owes nothing to others. On the contrary, he lives in society and must cooperate with others for his own good. But everyone remains free to cooperate or not and must assume the responsibility for their choices.

The notion of responsibility is corollary to freedom because every choice has consequences. The responsible person is the one who assumes the costs of their own choices and does not shift this cost onto others. In other words, freedom is demanding. It is a moral notion that implies rights but also duties towards others, including the duty to respect their freedom.

- Secondly, philosophy is normative, unlike history, which is merely descriptive. Thus, political philosophy is distinct from political sciences. Political philosophy is normative, meaning it prescribes values and judges human actions by a criterion of justice. On the other hand, political sciences are content to describe regimes, to make the history of institutions, without making value judgments.

Philosophy of freedom and philosophy of power

From this perspective, there are only two kinds of political philosophies: the philosophy of freedom and the philosophy of power.

- The philosophy of freedom is based on the natural right of property and asserts that the sole purpose of the law is to protect private property and contracts. Everyone should be able to do as they wish with what belongs to them, provided they do not harm anyone. It is a philosophy that defends equal freedom for all to dispose of oneself and one's property under the condition of responsibility. It is the philosophy of the free market.

- The philosophy of power justifies the authority of certain collective entities such as the State or society to decide the limits to be placed on the market and property, and therefore on freedom. In this framework, it is up to the law to organize the economy, health, housing, culture, education... This constructivist philosophy has always had its defenders, in the name of collective interest, equality, protection, and well-being.

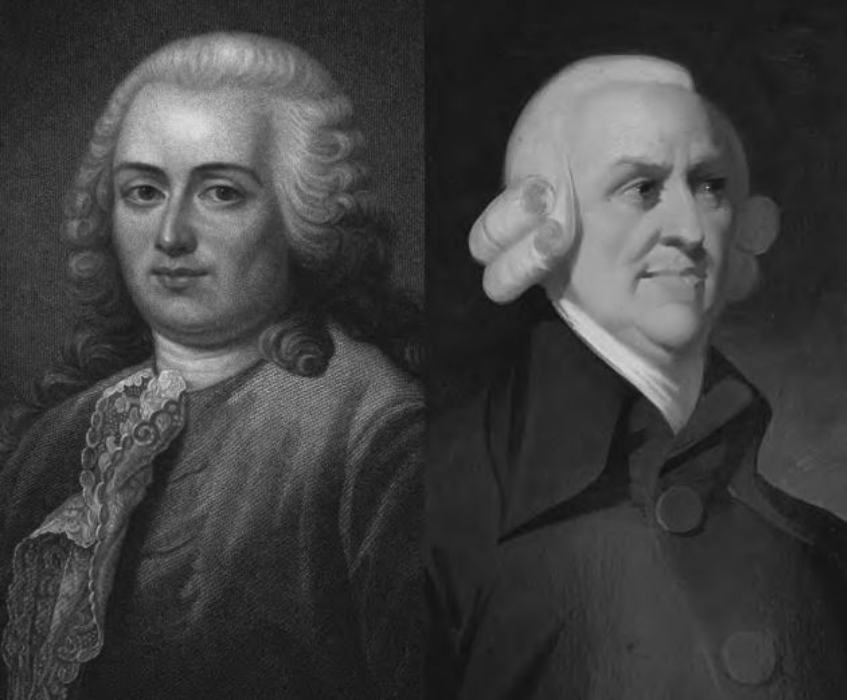

The antagonism between these two philosophies exists in all eras. But we can illustrate it with the philosophy of the Enlightenment. There is clearly a dividing line between two types of thinkers.

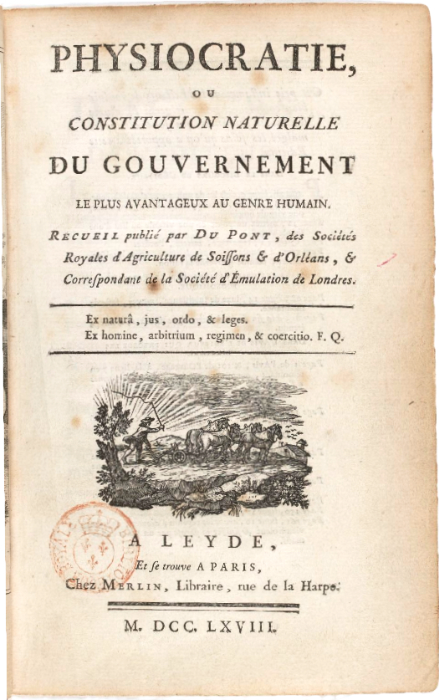

Those who defend the first philosophy in France are the Physiocrats, with François Quesnay at their head. They call themselves physiocrats (the name comes from the Greek Physis, which means nature, and Kratos, which means rule) because they develop an economic and social thought based on the natural rights of man. For them, society, people, and properties exist prior to laws. In this system, Bastiat explains,

It is not because there are laws that there are properties, but because there are properties that there are laws. (Property and Law).

For Turgot and Say, disciples of Quesnay, there exists a natural law, independent of the whims of legislators, which is valid for all men and predates any society. This philosophy comes directly from medieval scholasticism, the Stoics, Aristotle, and Sophocles. The unwritten laws are both prior to and superior to written laws because they stem from human nature and reason.

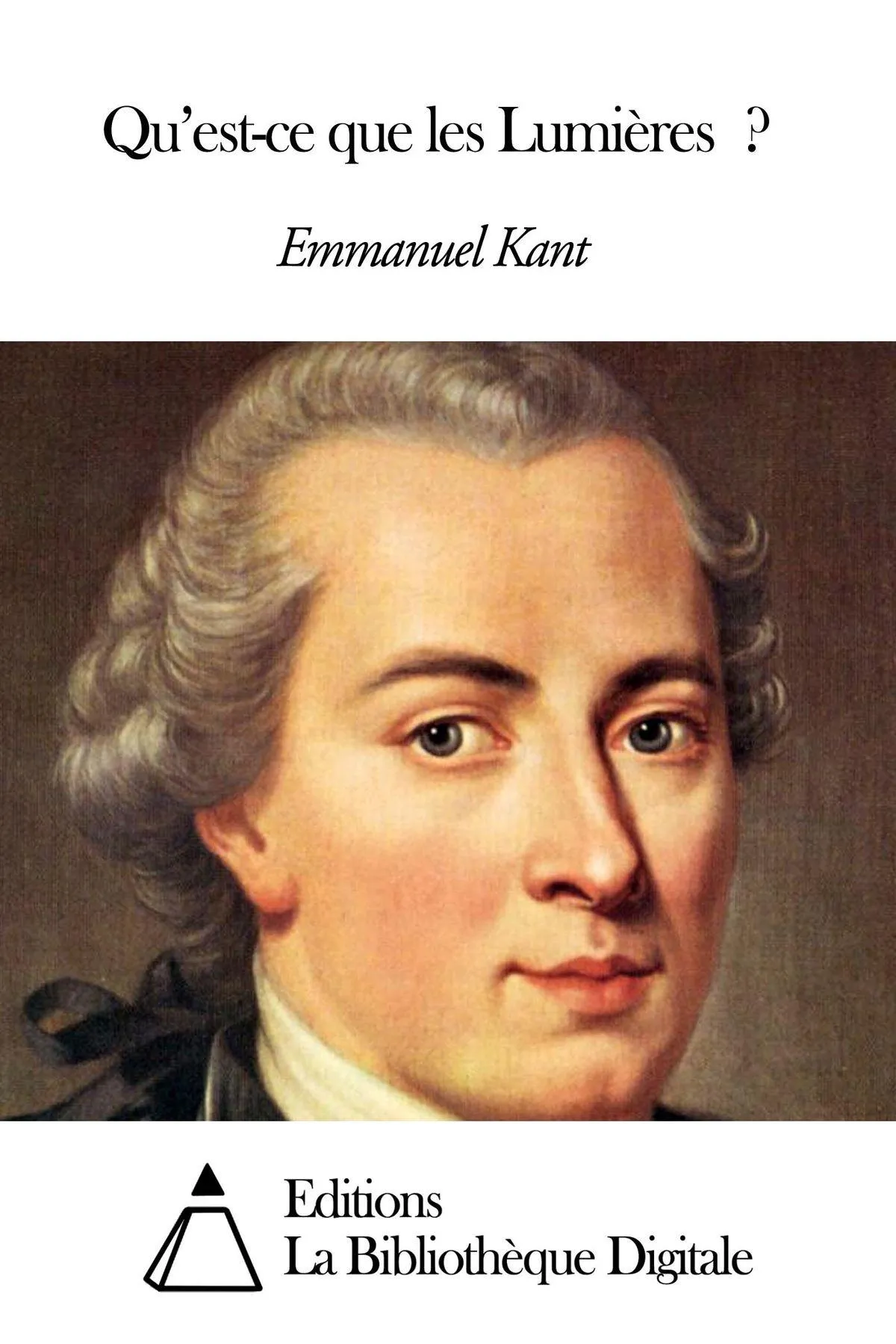

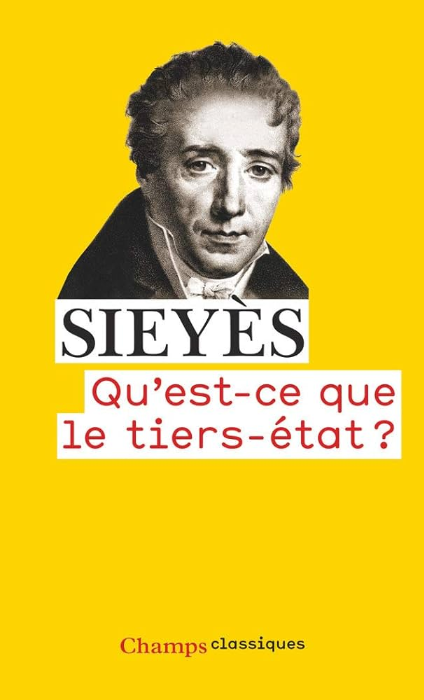

The second philosophy is found among authors like Rousseau, Robespierre, or Kant,

who embody the republican tradition for which the sovereignty of the general

will is the true source of law. A contemporary of Quesnay, Rousseau is an anti-physiocrat.

For him, the legislator must organize society, like a mechanic who invents a

machine from inert matter.

The second philosophy is found among authors like Rousseau, Robespierre, or Kant,

who embody the republican tradition for which the sovereignty of the general

will is the true source of law. A contemporary of Quesnay, Rousseau is an anti-physiocrat.

For him, the legislator must organize society, like a mechanic who invents a

machine from inert matter.

"He who dares to undertake the establishment of a people," says Rousseau, "must feel capable of changing, so to speak, human nature, of transforming each individual who, by himself, is a perfect and solitary whole, into part of a greater whole from which this individual receives, in a way, his life and being." (Social Contract)

From this perspective, the legislator's mission is to organize, modify, even abolish property if he deems it good. For Rousseau, property is not natural but conventional, like society itself. In turn, Robespierre establishes the principle that "Property is the right of every citizen to enjoy and dispose of the portion of goods guaranteed to him by law." There is no natural right to property; there are only an indefinite number of possible and contingent arrangements.

Frédéric Bastiat: production versus spoliation

When one opens textbooks, Bastiat noted, one learns that humanity would be doomed to nothingness without the intervention of power:

"It suffices to open, almost at random, a book of philosophy, politics, or history to see how deeply rooted in our country is this idea, born of classical studies and the mother of Socialism, that humanity is an inert matter receiving from power life, organization, morality, and wealth; — or worse, that humanity itself tends towards its degradation and is only stopped on this slope by the mysterious hand of the Legislator." (The Law).

In other words, the cultural prejudice dominating Western philosophy as well as historiography is that we owe everything to power: freedom, health, education, security, prosperity. Humanity is described as "inert matter" that takes shape thanks to the legislator.

But the reality of power is quite different according to Bastiat. Power is oppression. He writes: Open the annals of humanity at random! Consult ancient or modern history, sacred or profane, and ask yourself where all these wars of race, class, nations, and families come from! You will always get this unvarying answer: From the thirst for power. (Parliamentary Incompatibilities)

It is the thirst for power that is at the root of all forms of oppression in history. In a letter to Mrs. Chevreux, dated June 23, 1850, Bastiat outlines the phases of oppression: "Times of struggle, over who will seize the State; and times of truce which will be the ephemeral reign of triumphant oppression, a harbinger of a new struggle." First, the conquest of power through war, then the establishment of a State that subsists by plundering the wealth of its citizens.

History is thus a struggle between two principles: freedom and oppression:

Freedom! That is, in the end, the harmonious principle. Oppression! That is the dissonant principle; the struggle of these two powers fills the annals of mankind. (Economic Harmonies, conclusion of the original edition).

What is oppression?

In a word, it is plunder. Bastiat sketches the main types of plunder that come from the ruling elites: war, slavery, theocracy, and monopoly. Indeed, according to him: "There are only two ways to acquire the necessities for the preservation, embellishment, and improvement of life: PRODUCTION and PLUNDER." (The Physiology of Plunder)

What is the difference between production and plunder? Here is Bastiat's answer:

To produce, one must direct all one's faculties towards the domination of nature; for it is nature that must be fought, tamed, and enslaved. That is why iron converted into a plow is the emblem of production. To plunder, one must direct all one's faculties towards the domination of men; for it is they who must be fought, killed, or enslaved. That is why iron converted into a sword is the emblem of plunder. (Economic Harmonies, War).

In other words, production is power over nature. Plunder is power over men. However, there are two forms of plunder: legal and illegal. Illegal plunder is the theft or crime committed by one citizen against another. It is the action of the bandit or the swindler. However, the worst form of plunder is that which is accomplished by law: "There are people who think that plunder loses all its immorality provided it is legal. As for me, I cannot imagine a more aggravating circumstance." (What is Seen and What is Not Seen).

Bastiat tells us there are still two forms of legal plunder:

External plunder is called war, conquests, colonies. Internal plunder is called taxes, positions, monopolies. (Cobden and the League, Introduction).

In The Physiology of Plunder, he elaborates:

The true and equitable law of men is: Freely debated exchange of service for service. Plunder consists of banning by force or by deceit the freedom of debate in order to receive a service without rendering one. Plunder by force is exercised as follows: One waits for a man to produce something, then snatches it from him, weapon in hand. It is formally condemned by the Decalogue: Thou shalt not steal. When it happens from individual to individual, it is called theft and leads to prison; when it's from nation to nation, it is called conquest and leads to glory.

History of Plunder

Historically, ruling elites have always lived off plunder. Bastiat notes:

Force applied to plunder is the basis of human annals. To trace its history would be to reproduce almost entirely the history of all peoples: Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes, Persians, Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, Goths, Franks, Huns, Turks, Arabs, Mongols, Tartars, not to mention the Spaniards in America, the English in India, the French in Africa, the Russians in Asia, etc.

(Economic Sophisms, Conclusion of the first volume). Plunder, in its most brutal form, armed with torch and sword, fills the annals of human history. What are the names that summarize history? Cyrus, Sesostris, Alexander, Scipio, Caesar, Attila, Tamerlan, Muhammad, Pizarro, William the Conqueror; this is naive plunder through conquests. To it belong the laurels, monuments, statues, and triumphal arches. (Economic Harmonies, conclusion of the original edition). The history of the world is the history of how one group of people plundered others, often systematically, through war, slavery, theocracy. Nowadays, it is the monopoly, that is, economic privileges distributed by the State to its clients.

A few days before his death in Rome in 1850, Bastiat confided to his friend Prosper Paillottet:

An important task for political economy is to write the history of Plunder. It is a long history in which, from the beginning, appear conquests, migrations of peoples, invasions, and all the disastrous excesses of force in conflict with justice. From all this, there are still living traces today, and it is a great difficulty for the solution of questions posed in our century. We will not arrive at this solution until we have clearly established in what and how injustice, taking its share among us, has entrenched itself in our customs and in our laws.

(P. Paillottet, Nine Days Near a Dying Man)

Lord Acton: Freedom is the Engine of History

It is known, history is written by the victors. Attention is often focused on the conquest of power, on the lives of leaders in power, and on the conflicts that oppose them to those who wish to take their place.

This is particularly true of textbooks intended for public schools and written by professors employed by the State. This is not the case for a work in two volumes written by a historian from Cambridge in the 19th century, Lord Acton. His full name is John Emerich Edward Dalberg, Baron of Acton (1834-1902). He is the author of History of Liberty in Antiquity and Christianity. His work is considered one of the most important on the subject, and he dedicated a large part of his career to it. His work, although unfinished, is a powerful warning against the dangers of power abuse, and his advocacy for freedom and individual responsibility remains relevant today.

This author is best known for his maxim: "Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely." A formula that echoes that of Montesquieu in The Spirit of the Laws:

It is an eternal experience that every man who has power is tempted to abuse it.

Acton's Thesis

For Acton, the conflict between liberty and power is the central theme of human history, and liberty is the driving force of progress and the evolution of societies. Acton sought to understand the factors that contributed to the rise of liberty in the West. His goal was to identify the conditions necessary for its preservation and development. He studied philosophical ideas, social structures, and political contexts that favored its emergence over time.

His central thesis is that "liberty is established by the conflict of powers." According to Acton, for centuries after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Catholic Church was the only force capable of challenging the authority of feudal lords, monarchs, and emperors. This power struggle between the Church and the State proved crucial for the rise of liberty. Europe had a strong God and a weak power, due to the ongoing quarrel, in the Middle Ages, between popes and kings. In contrast, China had a weak deity and a strong bureaucratic power.

By liberty, I mean the assurance that every man will be protected, when he does what he believes to be his duty, against the influence of authority and majorities, of custom and opinion. The State is competent to set duties and to distinguish between good and evil only in its own immediate sphere.

(Lord Acton) In other words, freedom is the right for individuals to follow their own conscience, and it is not the state's role to dictate a person's conduct in philosophical, moral, and religious matters. Friedrich Hayek had initially considered naming the Mont Pelerin Society the "Acton-Tocqueville Society," in tribute to two thinkers he deeply admired: Lord Acton and Alexis de Tocqueville. Ultimately, it was the name of the location where the Society's first meeting was held, Mont Pelerin in Switzerland, that was chosen.

Voltaire and Condorcet

But the idea that freedom in Europe was born from internal struggles among various claimants to power, preventing the establishment of absolute domination, is not unique to Acton. It can already be found in thinkers such as Voltaire and Condorcet.

Thus, Voltaire, in his Philosophical Letters, attributes English freedom to conflicts between kings and nobles which prevented any excessive concentration of power. And he notes:

If there were only one religion in England, its despotism would be to be feared; if there were only two, they would cut each other's throats; but there are thirty, and they live in peace and happiness. (On the Presbyterians)

Condorcet, in his Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind, attributes the decentralized structure of power in Italy to the rivalry between the pope and the emperor, which allowed many independent city-states to survive.

This thesis is also found in a monumental work dating from 1983: Law and Revolution: The Formation of the Western Legal Tradition, by Harold J. Berman (French translation by Raoul Audouin, published by the University of Aix en Provence Bookstore in 2002). Berman's analysis highlights the crucial role of legal pluralism in the history of the West. This system, far from being a mere source of complexity, was a driver of development, freedom, and innovation, shaping the Western legal traditions enduringly.

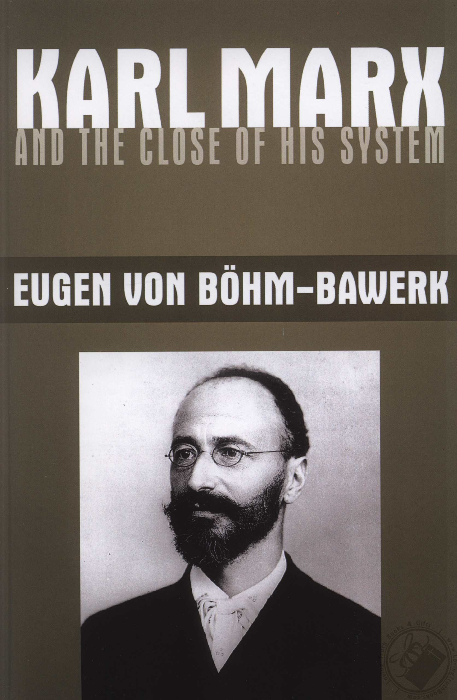

Marx: History as Class Struggle

438100e6-a385-55c6-b2c5-ad192c564757 Another perspective on history does

exist, however. It has been quite successful and long enjoyed the support of

Western intellectuals and representatives from the Global South. This is the

socialist and Marxist view of history.

It explains Europe's extraordinary growth primarily through the progress of technology combined with the "primitive accumulation" of capital, stemming from imperialism, slavery, the triangular trade, the expropriation of small peasants, and the exploitation of the working class. The conclusion is clear. This exceptional European growth was achieved at the expense of millions and millions of slaves and oppressed individuals.

Initially, Marx is right about one thing: history is the history of class struggles and exploitation. The quote is well-known, it's the first sentence of the first chapter of the Communist Manifesto: "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles." Marx himself acknowledged that he had borrowed his theory of class struggle from earlier authors:

I have no credit for discovering classes and class struggles in modern society. Long before me, bourgeois historians had described the historical development of this class struggle and bourgeois economists the economic anatomy of classes.

(Letter to J. Weydemeyer, March 5, 1852).

But he is mistaken about a fundamental point regarding the working class: it is not capital that produces exploitation. In other words, the class struggle does not take place within production but between those who pay taxes and those who collect them.

According to Marx, exploitation is a process that consists of extracting a portion of the value created by the worker without paying for it, which allows capitalists to make a profit. In other words, exploitation would be a mechanism that allows capitalists to enrich themselves by stealing the labor of the proletariat.

This analysis reflects a misunderstanding of surplus value and the cooperative and dynamic nature of economic life. Indeed, the profit that the entrepreneur receives is compensation for the risk they take, and the worker or employee is not a slave. In a competitive situation, they can accept or refuse a contract with their employer. They make a choice that reflects a cost-benefit analysis.

The Industrial Revolution in Question

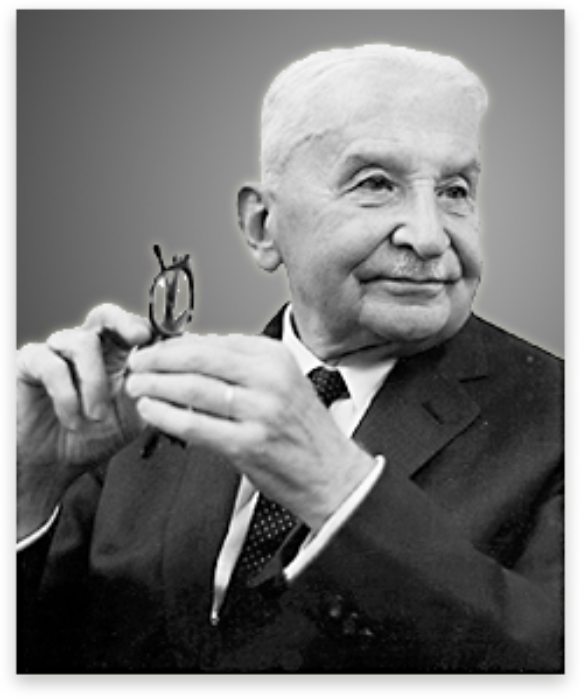

In fact, the Marxist analysis distorts the historical reality of the

Industrial Revolution. Ludwig von Mises clarified this issue in his

economics treatise Human Action (see especially the chapter titled Popular Interpretation of the Industrial Revolution) as well as in a series of lectures published under the title: Economic Policy: Thoughts for Today and Tomorrow. (Also worth reading, The Anti-Capitalistic Mentality here and here).

Mises explains that jobs in factories, although miserable by our standards, represented the best possible opportunity for workers of the time.

Let's read an excerpt from Human Action:

In the first decades of the industrial revolution, the living standards of factory workers were scandalously low compared to the conditions of their contemporaries from the upper classes, and compared to the present situation of industrial crowds. Working hours were long, the sanitary conditions of the workshops deplorable. The working capacity of individuals quickly exhausted. But the fact remains, that for the surplus population that the appropriation of communal grazing lands (enclosures) had reduced to the worst misery, and for whom there was literally no place within the framework of the reigning production system, factory work was salvation. These people flocked to the workshops, for the sole reason that they absolutely needed to improve their standard of living.

Mises adds that the improvement of the human condition was thus made possible by the accumulation of capital:

The radical change in situation that has conferred upon the Western masses the present standard of living (a high standard of living indeed, compared to what it was in pre-capitalist times, and to what it is in Soviet Russia) was the effect of capital accumulation through saving and wise investment by far-sighted entrepreneurs. No technological improvement would have been achievable if the additional material capitals required for the practical use of new inventions had not been made feasible by saving beforehand. Regarding Marxist historiography, we can also refer to Friedrich Hayek in Capitalism and the Historians (University of Chicago Press, 1954) and his chapter titled "History and Politics". According to Hayek, it was not industrialization that made workers miserable, as the dark legend of capitalism propagated by Marxism claims. He notes: The real history of the connection between capitalism and the rise of the proletariat is almost the opposite of what these theories of the expropriation of the masses suggest.

Before the Industrial Revolution, most people lived in rural societies and depended on agriculture for their survival. They had little to sell in the market, which limited their opportunities and their standard of living. Everyone expected to live in absolute poverty and envisioned a similar fate for their descendants. No one was outraged by a situation that seemed to be inevitable.

With the advent of industrialization, new opportunities emerged, creating a growing demand for labor. For the first time, people without land or significant resources could sell their labor to factories and manufactures in exchange for a wage, ensuring security for the future.

This new access to income allowed them to feed and house themselves, even in rapidly expanding cities. Thus, the Industrial Revolution fostered a population explosion that would not have been possible under the economic stagnation conditions of the pre-industrial era.

This is how, Hayek remarks, "economic suffering became both more visible and seemed less justified, because general wealth was increasing faster than ever before."

Therefore, the worker was not exploited, even if wages were low, due to the abundance of labor fleeing the countryside.

In reality, exploitation only makes sense as an aggression against private property. In this sense, exploitation is always the act of the State. For the State is the only institution that obtains its revenues through coercion, that is, by force. Thus, the real exploitation, as we have seen with Bastiat, is that of the productive classes by the class of state officials. It would be more accurate to say that the history of all society up to our days is nothing but the history of the struggle between plunderers and the productive classes.

The "European Miracle"

Subsequently, a more nuanced historical analysis than that of Marx allows us to challenge the idea of a predatory Europe, which owes its success solely to imperialism and slavery. By delving into comparative economic history, some contemporary historians have sought the origins of Europe's development in what distinguished it from other major civilizations, particularly those of China, India, and Islam. These characteristics have been explored by David Landes, Jean Baechler, François Crouzet, and Douglass North. These researchers have attempted to understand what is referred to as the "European miracle." They focused their attention on the fact that Europe was a mosaic of divided and competing jurisdictions, where, after the fall of Rome, no central political power was capable of imposing its will.

As Jean Baechler, a member of the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences, says in The Origins of Capitalism (1971):

The first condition for the maximization of economic efficiency is the liberation of civil society from the State (...) The expansion of capitalism owes its origin and raison d'être to political anarchy.

In other words, the great "non-event" that dominated Europe's destiny was the absence of a hegemonic empire, like the one that dominated China.

It is this radically decentralized Europe that produced parliaments, diets, and Estates-General. It gave birth to charters like the famous Magna Carta of the English, but it also produced the free cities of Northern Italy and Flanders: Venice, Florence, Genoa, Amsterdam, Ghent, and Bruges. Finally, it developed the concept of natural law, as well as the principle that even the Prince is not above the law, a doctrine rooted in the medieval universities of Bologna, Oxford, and Paris, extending to Vienna and Krakow. In conclusion of this chapter, Europe's economic and cultural takeoff was not due to the conquest and exploitation of the rest of the world. It dominated the world thanks to its economic progress. What has been called "imperialism" is the consequence, not the cause, of Europe's economic progress. But to return to Lord Acton, what distinguishes Western civilization even more from all others is its affirmation of the value of the individual. In this sense, freedom of conscience, especially in religious matters, has been a fundamental pillar of this civilization. We will return to this in the following section.

Murray Rothbard: State versus Society

In the last chapter of Anatomy of the State (translated into French as L’anatomie de l’Etat, by Résurgence editions), Murray Rothbard proposes a theory of history. This very short chapter is titled: History, a race between state power and social power. According to Rothbard, history can be understood as a perpetual conflict between two fundamental principles:

- Peaceful cooperation and production, which represent voluntary exchange and the creation of wealth through labor and innovation.

- Coercive exploitation and predation, embodied by the domination of the State, which appropriates the fruits of individuals' labor by force.

Referring to Albert J. Nock, Rothbard uses the terms "social power" and "state power" to designate these two opposing forces:

- Social power: emerges from the cooperation and ingenuity of free individuals, leading to economic progress and prosperity. It is a power over nature, the creative capacity of man to transform nature into resources and knowledge, for the collective good of society.

- State power: is imposed through coercion and violence, seeking to control and exploit society for its own benefit. It is a power exercised over man. It consists of "draining the fruits of society for the benefit of non-productive (in fact, anti-productive) leaders."

The State as a Parasite

Rothbard considers the State as a parasite that lives at the expense of the productive society. It seizes "command posts" strategically to appropriate wealth and power. Monopoly of force, justice, education, infrastructure. And he adds, "In the modern economy, money is the essential command post." For Rothbard, the principle of freedom should also apply to money. If we are in favor of freedom in other sectors, if we want to protect property and the person against the intrusion of the State, our most urgent task must be to explore the possibility of a free market for money. (See on this point his essay: State, What Have You Done with Our Money? Translation by Stéphane Couvreur for the Institut Coppet, 2011).

The Failure of Attempts to Limit the State

Rothbard warns against the idea that written constitutions, by themselves, could guarantee freedom and the limitation of power:

The last centuries were times when men tried to impose constitutional and other limits on the State, only to find that such limits, like all other attempts, had failed. Of all the many forms that regimes took over the centuries, of all the concepts and institutions that were tried, none succeeded in keeping the State under control.

A written constitution certainly has many advantages, but it is a serious mistake to assume that it would be sufficient. Indeed, the majority party, with its power, can adopt an extensive interpretation to increase its power. Without concrete mechanisms to enforce rights, and faced with a dominant party determined to extend its power, constitutions risk becoming ineffective, misleading tools.

The 20th Century: A Century of Retreat

According to Rothbard, history is not a linear process, but rather an oscillation between the advancement of social power and the resurgence of control by the State:

- Periods of freedom: when social power flourishes, freedom, peace, and prosperity increase.

- Periods of state domination: when the State gains the upper hand, leading to oppression, war, and regression.

From the 17th century to the 19th century, in many Western countries, there were periods of acceleration of social power and a corresponding increase in freedom, peace, and material well-being. But Rothbard reminds us that the 20th century was marked by a resurgence of State power, with dire consequences: an increase in slavery, war, and destruction:

During this century, the human race faces, once again, the virulent reign of the State; the State now armed with the creative power of man, confiscated and perverted for its own ends. What is a free society, after all? It's a society without monopoly. In his work of political philosophy, Ethics of Liberty (1982), Rothbard answers: "a society in which there is no legal possibility of coercive aggression against an individual's person or property." This is why, according to him, political philosophy, which must define the principles of a just society, boils down to one single question: "Who legitimately owns what?"

For Rothbard, social order can prevail if it is the product of the generalization of contractual procedures for the free exchange of property rights, by privatizing all economic activities and even sovereign functions (central bank, courts) and by resorting to competition among protection agencies.

And he adds:

We have now tasted all the variants of statism, and they have all failed. Everywhere in the Western world at the beginning of the 20th century, business leaders, politicians, and intellectuals had started to call for a "new" mixed economy system, of state domination, in place of the relative laissez-faire of the previous century. New panaceas, attractive at first glance, like socialism, the corporatist state, the Welfare-Warfare state, etc., have been tried and all have manifestly failed. The arguments in favor of socialism and state planning now appear as pleas for an aged, exhausted, and failed system. What is left to try but freedom?

(Ethics of Liberty)

The origins of freedom: Antiquity

The invention of critical rationality by the Greeks

The experience of Athenian democracy has left a lasting mark on the history of political thought and continues to inspire ideals of democracy and citizen participation in today's world.

Athenian democracy was characterized by lively public debate on city affairs, which primarily took place in the agora, the marketplace. This mode of operation, based on reason and critical discussion, sharply contrasted with earlier practices where laws and customs were considered sacred and immutable, handed down by ancestors and protected by the gods.

The birth of politics with the city

Athenian democracy represents a major break from past traditions. Indeed, in

earlier societies, there could not be "politics" in the sense of a

discussion about social rules, since these were imposed in a transcendent

manner by myth.

Historian Jean-Pierre Vernant writes:

The emergence of the polis constitutes, in the history of Greek thought, a decisive event. Certainly, in terms of intellectual development and in the realm of institutions, its full consequences would only be realized in the long term; the polis would go through multiple stages, various forms. However, from its advent, which can be placed between the 8th and 7th centuries, it marks a beginning, a true invention; through it, social life and relations among men take on a new form, the originality of which the Greeks would fully feel. (...) What the polis system implies first and foremost is an extraordinary preeminence of speech over all other instruments of power. It becomes the political tool par excellence, the key to all authority in the state, the means of command and domination over others. (...) A second characteristic of the polis is the nature of full publicity given to the most important manifestations of social life. One could even say that the polis exists only insofar as a public domain has emerged, in two different, yet interconnected senses of the term: a sector of common interest, as opposed to private affairs; open practices, established in broad daylight, as opposed to secret procedures. (...) Henceforth, discussion, argumentation, controversy become the rules of the intellectual game, as well as the political game. The constant control of the community is exercised over the creations of the mind as well as over the state's magistracies.

(Jean Pierre Vernant, The Origins of Greek Thought, Paris, P.U.F, 1962)

The Greek word "polis," which gives "politics" in French, means the city-state. When Aristotle writes that "man is by nature a political animal," it does not mean he is made for power. By politics, he refers to the faculty men have to deliberate in the public square to determine what is just and unjust.

This novelty is based on the fundamental distinction between two terms in the Greek language, "phusis" and "nomos," which designate two types of laws:

- Phusis is the law of nature (which gives the word "physics" in French).

- Nomos is human law (a term found in the word "autonomy," which means "to obey one's own law"). The City emerges with the idea that the law (nomos) is of human origin, that it can be freely modified by humans, unlike nature, and can apply to all. The Greeks then become aware of the autonomy of the social and political order in relation to the natural order. This marks the appearance of politics: the ongoing discussion about the very rules of social life. From now on, problems will be resolved through concerted action and not by an immutable sacred order.

And Jean-Pierre Vernant adds:

Greek reason is the one that, in a positive, reflective, methodical way, allows us to act upon men, not to transform nature. Within its limits as in its innovations, it is the daughter of the city.

The Idea of Freedom Under the Law

Social harmony is not produced by the intentional action of the gods, but by the obedience of all citizens to the same impersonal law. Power is no longer the affair of priests, it has become the affair of all. Thus emerges the notion of equality before the law: "isonomia," but also rhetoric. Mastery of speech was essential to convince one's fellow citizens in assemblies and courts.

For Aristotle, tyranny is obedience to a man, and freedom is obedience to the law. He is credited with this quote:

To desire the rule of law is to desire the exclusive reign of reason. To desire instead the rule of a man is to add that of a wild beast, for desire and anger distort the judgment of rulers, even if they are the best of men.

According to him, laws, being impersonal and permanent, guarantee justice and equality for all citizens.

Cicero, the famous Roman orator and philosopher of the 1st century BC, took up this idea: "We are slaves of the laws so that we may be free" (De Republica, Book III, chapter 13). In this passage, Cicero develops an argument in favor of a republic governed by laws, rather than by one man or a small group of men. The idea of the republic is one that comes from Greek philosophy. It has often been contrasted with democracy, deemed too risky. Plato titled his main work of political philosophy: The Republic, and he judges democracy very harshly. When the people govern, there is a strong risk of imposing the law of their desires and confusing the good with the pleasant. Hence the tragic death of Socrates, condemned to death by a popular jury, manipulated by the sophists. Plato learned all the lessons from this.

Aristotle would use the term republic to designate the just constitution, the one that aims for the common interest and treats citizens as free men. A true regime of freedom is one where the law is general, equal for all, anonymous, and not a personal command.

The idea of freedom under the law is also found in the Anglo-Saxon term "Rule of Law".

Political Freedom

It can be said that the Greeks invented the concept of political freedom, in opposition to tyrannical domination. The Greeks of that era considered slavery to be a natural institution and that slaves did not have the same status as citizens. This may seem contradictory to the idea of freedom, but for them, freedom was linked to citizenship and not to the absence of slavery.

Herodotus, in Historia and Aeschylus in his tragedy The Persians, brilliantly illustrate the contrast between the absolute and tyrannical monarchy of Xerxes and the spirit of freedom of the Greeks. This people, characterized by the absence of masters and the refusal to submit to slavery by barbarians, no matter how numerous, finds its strength in the law, the "nomos", its true master that guarantees its freedom. And this law emanates from the will of all.

According to Jacqueline de Romilly: The Greeks themselves seem to have measured this originality and became aware of it at the beginning of the 5th century, in the shock that opposed them to the Persian invaders. And the first fact that struck them was that there was a political difference between them and their adversaries, which commanded everything else. The Persians obeyed an absolute sovereign, who was their master, whom they feared, and before whom they prostrated themselves: these practices were not common in Greece. There is an astonishing dialogue in Herodotus, which opposes Xerxes to a former king of Sparta. This king announces to Xerxes that the Greeks will not yield because Greece always fights against enslavement to a master. It will fight, no matter the number of its adversaries. For, if the Greeks are free, "they are not free in everything: they have a master, the law, which they fear even more than your subjects fear you."

(Ancient Greece at the Discovery of Freedom, Paris, Editions de Fallois, 1989)

Herodotus is convinced that a people of free men is a people who obeys a law and not a master, as in the Persian empire where only one man is free and all the others are slaves. This is true for Athens, a democracy, but it is also true for Sparta. The king does not create the law, he does not impose his will. He ensures the respect of the law, he is at its service and he dies, if necessary, to defend it.

The Quest for Truth and Pluralism

Moving away from mythological thought, Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes, and later Democritus and Empedocles, were the first to seek to understand phusis (nature) through reason and not through supernatural entities.

The fundamental principle posited by these early Pre-Socratic philosophers is that the elements of the kosmos (the universe) hold in place because they are all equally subject to the same "law of nature" (phusis) that can be stated in a universal and necessary manner. The universe is rational, it constitutes a structured whole, which man can discover with his reason (the "logos" as opposed to the "mutos", the myth).

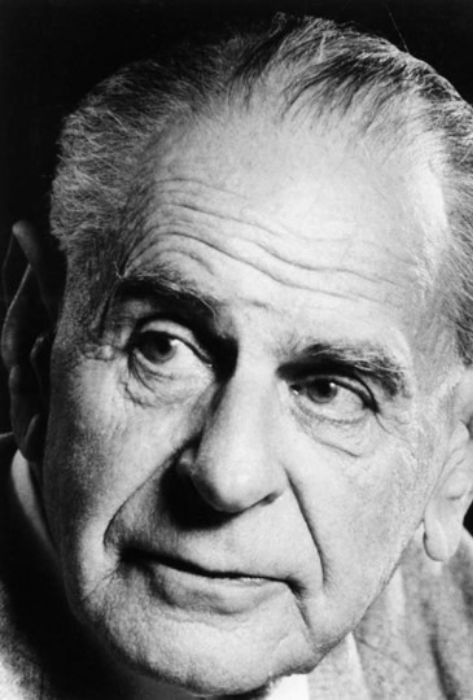

According to Karl Popper, we owe to the philosophers of ancient Greece, particularly the Pre-Socratics, the invention of critical rationalism, that is, the Western tradition of critical discussion, the source of scientific thought and pluralism. He explains this in a chapter of Conjectures and Refutations titled "Return to the Pre-Socratics": Regarding the first signs of the existence of a critical attitude, of a new freedom of thought, they appear in Anaximander's critique of Thales. This is a quite singular phenomenon, the thinker whom Anaximander criticizes is his master, his compatriot, one of the Seven Sages, the one who founded the Ionian School. According to tradition, Anaximander was only fourteen years younger than Thales, and he likely formulated his critiques and presented his new concepts during his master's lifetime (they died, it seems, a few years apart). However, no evidence of dissent, quarrel, or schism is found in the sources.

These elements indicate, according to him, that it was Thales who originated this new tradition of freedom, based on an original relationship between master and disciple. Thales was able to tolerate criticism and, moreover, he established the tradition of acknowledging it. Popper identifies here a break from the dogmatic tradition, which allows only a single school doctrine, to replace it with pluralism and fallibilism.

Our attempts to grasp and discover the truth are not definitive but are capable of improvement, our knowledge, our body of doctrine are conjectural in nature, they are made of assumptions, hypotheses, and not of certain and final truths.

The only means we have to approach the truth are criticism and discussion. From ancient Greece, therefore, comes this tradition:

Which consists of formulating bold conjectures and exercising free criticism, a tradition that was at the origin of the rational and scientific approach and, consequently, of this Western culture that is ours and the only one that is founded on science even if, obviously, this is not its only basis.

The invention of law by the Romans

The Roman Empire was a vast cosmopolitan entity. At its peak, around 117 AD, it was an immense multiethnic and multilingual state:

- In the west, it extended from Great Britain (present-day England) to Spain, passing through Gaul (present-day France) and the north of Africa.

- In the north, it reached the Rhine and the Danube, encompassing parts of Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria.

- To the south, it bordered the Mediterranean Sea, including Italy, Greece, the Balkans, Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt, and Cyrenaica (part of present-day Libya).

- To the east, it extended to Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) and Armenia.

From then on, the Romans advanced the development of law far beyond the Greeks, who lived in small, ethnically homogeneous city-states. Under the Roman Republic, there was already legal protection of property and individual rights.

Indeed, the function of law was to make peaceful cohabitation and exchange among people possible, by delineating the boundaries of "mine" and "yours."

Private property took on a new dimension in Roman civilization that it had not known before, even in Greek civilization.

Roman law would become the foundation of all modern Western laws during the Middle Ages and up to our times.

The protection of individual rights

Finally, Roman law placed great importance on the rights and freedoms of individuals, and Roman citizens were proud of their citizen status. The Law of the Twelve Tables (450 BC) constituted the first corpus of written laws accessible to all Roman citizens, both patricians and plebeians. This codification helped to clarify and standardize the law, which was previously scattered and often customary, ensuring a certain level of transparency in the application of the right to marry, buy, sell, etc.

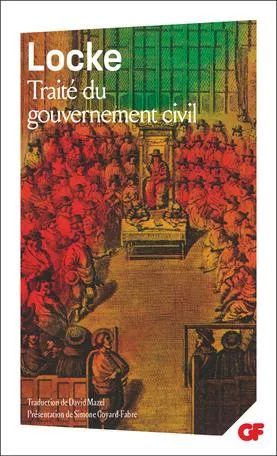

This law corresponds astonishingly to the fundamental natural rights as theorized by John Locke two thousand years later. It allows for the protection of individual rights against arbitrariness and abuses of power.

Certainly, women, slaves, and foreigners were still excluded from the full protection of the law. Nevertheless, the Law of the Twelve Tables represented a significant progress and a basis for the further development of individual rights extended to all.

The Law of the Twelve Tables notably places particular importance on property rights:

- It defines the different types of property (land, movable, etc.)

- It breaks down property into usus (right of use), fructus (right to receive the fruits), and abusus (right to alienate)

- It specifies the conditions for the acquisition, transmission, and protection of these goods.

In summary, it contributes to securing transactions and protecting individuals against arbitrary expropriations, with the possibility of recourse in case of dispute.

The Birth of Humanism and Private Life

What one is depends on what one has. Being is not as independent of having as is sometimes said because what we possess distinguishes us from what others possess. And our life belongs to us, we first own our faculties, our body before owning material goods.

In Roman society, everyone could increasingly differentiate themselves from others and thus become the actor of their own life. Man now plays a unique role, and Cicero uses the word "persona" to designate him. The "persona" was a mask worn by Roman actors, but it also referred to the legal and social personality of an individual. The notion of persona implied that individuals were distinct entities with their own rights and responsibilities. The concept of the individual human person (the ego) with its inner life and unique destiny was born, and it would develop with Christianity.

Moreover, Roman literature and philosophy contain many examples of reflections on the nature of the individual, happiness, wisdom, and life in society.

Seneca and the Happy Life

A model of balance in thought is Seneca, a Roman Stoic philosopher who wrote about the importance of virtue, reason, and self-control. A contemporary of Jesus, he was at the same time a tutor to Nero, a wealthy banker, and a famous Roman writer.

The Treatise on the Happy Life (De Vita Beata) is a plea for Stoic morality. Happiness, says Seneca, "is a free soul [...] inaccessible to fear [...] for whom the only evil is moral indignity." A disciple of Socrates, the Stoic sage does not fear physical evil, death, or even suffering injustice. For him, the only evil is moral evil. Therefore, the supreme good lies in virtue.

However, pleasure is not incompatible with virtue:

The ancients prescribed living the best life, not the most pleasant, in such a way that pleasure is not the guide of right will, but its companion on the road.

That's why the wise man does not reject the gifts of fortune:

He does not love riches, he prefers them; he does not welcome them into his heart, but into his house; he does not reject what he possesses, he dominates them and wants them to provide his virtue with ample matter.

Seneca goes even further. For the wise man, riches are the occasion and the means to exercise virtue: In poverty [...] there is only one kind of virtue: not to falter or let oneself be depressed; amidst wealth, temperance, generosity, discernment, economy, and magnificence have free rein.

The Concept of a Higher Law

The term "human rights," which many jurists rally around, implicitly subscribes to the idea of a higher law because it targets rights linked to humanity itself before any positive legislation. Without this superior moral norm, there would no longer be a critical authority capable of interpreting and questioning the legal order.

This idea reminds us that the Prince (just like political leaders) does not possess justice itself but is himself subject to a law that surpasses him and must regulate his judgment.

This is what philosophers of Antiquity, especially the Romans like Cicero or the Stoics, called natural law. Its origins can be found in Greek thought, with Sophocles and Aristotle.

Aristotle distinguishes between natural justice and legal justice. Natural justice is what is universally valid, in every place and at all times. It is an unwritten law, known through reason. Legal justice is what is in itself indifferent but becomes mandatory for everyone as a result of a conventional choice and is written in a legal text. In other words, a distinction is made between natural law and positive law.

The playwright Sophocles, in his play Antigone, stages a conflict between divine law and human law. Antigone refuses to obey King Creon's decree that forbids the burial of her brother, arguing that divine laws, immutable and superior, take precedence over human laws.

When Antigone disobeys Creon, she opposes positive law to obey her moral and religious conscience. If there is only positive law, says Aristotle, Creon is always right, even when he is wrong. But if we maintain the regulatory idea of a natural or divine law, Antigone can stand up when the time comes and invoke against an unjust law, the superior right of the unwritten law.

Cicero and Natural Law

Cicero lived in the 1st century BC and is considered the greatest orator of the Latin language under the Roman Empire. He is also a moral and political philosopher close to the Stoics. His essays have been read by educated Europeans for many centuries.

In his treatise On the Laws (De Legibus), he reflects on

the foundation of law. According to him, positive law, the set of

conventions or written laws adopted by a society, cannot establish justice

worthy of the name. There exists a natural justice, inscribed in human

reason: "law has a foundation in nature itself." To say that just and unjust

are the result of a convention is to say that truth is decreed. However,

truth cannot be decreed, even by the majority, it guides our judgments.

Cicero also rejects utility as the foundation of law. Indeed, he writes:

In his treatise On the Laws (De Legibus), he reflects on

the foundation of law. According to him, positive law, the set of

conventions or written laws adopted by a society, cannot establish justice

worthy of the name. There exists a natural justice, inscribed in human

reason: "law has a foundation in nature itself." To say that just and unjust

are the result of a convention is to say that truth is decreed. However,

truth cannot be decreed, even by the majority, it guides our judgments.

Cicero also rejects utility as the foundation of law. Indeed, he writes:

If justice is the obedience to written laws and to the institutions of peoples and if, as those who maintain it say, utility is the measure of all things, he will despise and break the laws, who believes to see his advantage in it. Thus, no more justice, if there is not a nature of justice at work; if it is based on utility, another utility overturns it. If, therefore, the right does not rest on nature, all virtues disappear. What becomes, indeed, of liberality, love of country, respect for things that must be sacred to us, the will to serve others, the willingness to recognize service rendered? All these virtues arise from the inclination we have to love men, which is the foundation of law.

Therefore, according to him, there is a universal justice, inscribed in reason and nature. Cicero writes in the De Republica:

The true law is right reason in agreement with nature; it is of universal application, unchanging and eternal; it invites to duty by its commands and turns away from the wrong path by its prohibitions […]. Neither the Senate nor the people have the power to dispense us from obeying it […]. It is not one thing at Athens and another at Rome, not one thing today and another tomorrow. But it is a single and same law, eternal, immutable, in force at all times and among all peoples […]. Whoever does not obey this law flees from himself and despises his own human nature.

This law is superior to the legislations in force, hence, "it cannot be invalidated by other laws, nor can any of its precepts be derogated, nor can it be entirely abrogated," adds Cicero. Political power has no hold on it.

Neither truth nor justice can be decreed, even by the majority, for otherwise they become the object of all manipulations. Therefore, even if the ruler is the people, it is not right to transgress the principles of natural law. Asserting that law cannot be reduced to merely the statutes enacted by the legislature, Cicero aimed to fight against legislative arbitrariness and propose a political morality. This idea has had a lasting influence on Western thought.

The Fall of Rome

Why did Rome decline and ultimately fall? Many like to think that the Roman Empire collapsed suddenly, under the impact of barbarian invasions. However, the causes of the Roman Empire's collapse are to be found much earlier, in imperialism and economic and monetary dirigisme.

In 1734, in his Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and of Their Decline, Montesquieu developed an original and unified thesis to explain the rise and fall of Roman power: the freedom gained under the Republic and then lost under the Empire. From the moment Roman domination expanded, freedom was lost, and decadence set in.

The Roman Empire was a parasitic military regime, which could only survive through a constant influx of plundered wealth from outside, prisoners reduced to slavery, and stolen lands.

Indeed, the enrichment of the Roman aristocracy came only from the booty of invasions and not from any creation of value. But with the end of conquests and the diminishing returns from plundering, the administration had to resort more and more to tax increases to satisfy its need for wealth, which led to a general impoverishment of the Empire's population.

Bread and Circuses

Around 140, the Roman historian Fronto wrote:

Roman society is primarily concerned with two things, its food supplies and its spectacles.

Gladiator fights, chariot races, and theatrical performances, often free, attracted huge crowds and allowed the elites to win the favor of the people. The power provided games to its citizens, but also wheat, bread, pork, and olive oil. This strategy served as a political strategy to ease social tensions, divert attention from economic problems, and strengthen the power of the emperors.

Under the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius (from 138 to 161), the Roman bureaucracy reached gigantic proportions. But as tax revenues were not sufficient to fund the administration and garrisons, emperors began to issue more and more currency by reducing the amount of silver in each coin. The Denarius, the main currency of Rome, saw its silver content drop from 100% to 0.5% between 235 and 284 AD. With the devaluation of the currency, prices increased uncontrollably, leading to a decrease in consumption, trade, and confidence.

The fall of the Roman Empire was a slow process, directly linked to the bankruptcy of a corrupt monetary system. The hyperinflation that ensued caused the economy to collapse and led to the loss of people's confidence in the currency.

Then political instability was added to the economic instability, with more than 50 different emperors on the throne in 50 years.

Price Control

A classic example of interventionism emerged in Rome when Emperor Diocletian wanted to cap prices. Interventionism is defined as the action of a power that goes beyond its role of maintaining order and protecting citizens. It is an attempt to control the market, aiming to modify prices, wages, interest rates, and profits.

The repeated monetary emissions by successive emperors to cope with the increase in military expenditures had caused a surge in prices. In 301, Diocletian proclaimed the Edict of Maximum in an attempt to cap them. It was a failure.

Ludwig von Mises describes this episode, which well illustrates the harmful effects of interventionism: Roman Emperor Diocletian is well-known for having been the last Roman emperor to persecute Christians. Roman emperors, in the latter part of the third century, had only one financial method, which was to debase the currency. In these primitive times, before the invention of the printing press, inflation itself was primitive, so to speak. It involved fraud in the minting of coins, especially silver, until the color of the alloy was changed and the weight significantly reduced. The result of this debasement of the currencies, coupled with the corresponding increase in circulation, was a rise in prices, followed by an edict of price control. And the Roman emperors did not hold back in enforcing the laws; they did not consider death too severe a penalty for a man who had asked for too high a price. They enforced price controls, but as a consequence, they brought down society. This eventually led to the disintegration of the Roman Empire, and also to the breakdown of the division of labor. (Economic Policy, Reflections for Today and Tomorrow)

From Liberalism to Socialism

Following in the footsteps of Montesquieu, Philippe Fabry demonstrates that Rome experienced a trajectory from liberalism to socialism. Philippe Fabry is a historian of law, institutions, and political ideas. He has taught at the University of Toulouse 1 Capitole and is the author of several books, including Rome, from Liberalism to Socialism, 2014.

Was Rome the greatest liberal power of the ancient world? Did it then fall into a form of socialism? Let's first define the terms:

Liberalism: trust in the action of individuals, producing a spontaneous order, just because it results from their voluntary interactions, through the free play of the market and the respect for their inalienable rights.

Socialism: the organization by the State of society considered as a whole, through the planning of production and consumption.

The thesis of Philippe Fabry's book is that "the fall of the Roman Empire is the consequence of the deadlock into which imperial socialism had led the ancient world." It was the dirigisme of the Roman imperial state that led to its collapse. The Roman Republic, which was the greatest liberal power of the ancient world, lasted from 510 BC to 23 BC, nearly 500 years. However, gradually, the civic collegiality that characterized the Roman Republic disappeared in favor of personal power embodied by emperors who adopted the style of government of the oriental potentates of ancient Egypt and Persia. Breaking with a previously moderate foreign policy, Rome suddenly subdued vast populations through war, providing streams of slaves to wealthy Roman investors, ruining the middle classes. In return, the Roman population demanded more and more subsidies.

In the early days of its greatness, each Roman considered himself as the main source of his income. What he could voluntarily acquire in the market was the source of his livelihood. Rome's decline began when a large number of citizens discovered another source of income: the political process or the redistributive state.

Romans then abandoned freedom and personal responsibility in exchange for promises of privileges and wealth distributed directly by the government. Citizens adopted the idea that it was more advantageous to obtain income through political means rather than through labor.

Philippe Fabry summarizes:

the observed weaknesses of the imperial system […] are those of all totalitarian regimes: "Absolute priority given to maintaining the system in place, inefficiency in economic production, corruption, cronyism.

And he adds:

In total, the economic, political, artistic, and religious life under the Roman Empire in the 4th century must have been quite similar to what it was under Brezhnev in the USSR (and in the worst moments under Stalin) or to what it can be today in North Korea: the entire population of the Roman world was regimented by imperial socialism and suffered, directly or indirectly, its effects.

The origins of freedom: the Middle Ages

The affirmation of human freedom

The Christian idea of freedom developed in the medieval theology of Saint Augustine in the 4th century, to Saint Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century. What is this idea?

Freedom is implicated in the idea of sin

Right from the start, Christianity teaches that sin is a personal matter, not inherent to the group, but that each individual must take responsibility for their own salvation. "God has endowed his creature, with free will, the capacity to do wrong, and thereby, the responsibility for sin," asserts Saint Augustine in his treatise on free will, De Libero Arbitrio. Sin cannot exist without freedom. Indeed, the Christian God is a judge who rewards "virtue" and punishes "sin". But this conception of God is precisely incompatible with fatalism because a person could not be guilty and make their mea culpa if they were not first free to determine their own behavior. To acknowledge one's moral fault, one's guilt, is to recognize that one could have acted differently.

"Why do we do wrong?" asks Saint Augustine. If I am not mistaken, the argument has shown that we act this way through the free will of the will. But this free will to which we owe our ability to sin, we are convinced, I wonder if He who created us did well to give it to us. It seems, indeed, that we would not have been exposed to sin if we had been deprived of it; but it is to be feared that, in this way, God also appears as the author of our bad actions. (De libero arbitrio, I, 16, 35.)

If God wanted man to be able to do wrong, isn't He then indirectly responsible for evil? Why did God want the possibility of evil? Saint Augustine answers:

the free will without which no one can live well, you must recognize that it is a good, and that it is a gift from God, and that those who misuse this good should be condemned rather than saying of the one who gave it that he should not have given it.

Saint Augustine's response to the problem is to say that God is responsible for the possibility of evil but not for its realization. He wants the possibility of evil because this possibility is necessary for freedom without which there is no responsibility, that is, no access to the dignity of moral life.

But the realization of moral evil is the work of man, who makes bad use of his freedom, and not of God who wants man to choose the good.

In summary, freedom is a good because it allows one to order oneself to the good and to God who is the absolute good, but it necessarily and simultaneously implies the possibility to choose evil and to reject God.

God does not do good in our place

In medieval theology, providence is not a constant intervention of God in

the lives of men, as if God acted in our place and without our consent. On

the contrary, God gives to each creature, according to its nature, faculties

that allow it to provide for itself and thus reach its full development. God

does not do the good for the creature in its stead.

And the higher we go in the scale of beings, from mineral to man, the more God delegates to his creature the power to act on its own. He entrusts man with the freedom to govern himself and to govern the world with his reason, according to the virtue of prudence.

Thus, Saint Thomas writes (Summa contra Gentiles, III, 69 and 122):

To take away from the perfection of creatures is to detract from the perfection of divine power (...) God is offended by us only because we act against our own good.

Providence, therefore, gives us the means to be our own providence. And he adds:

A man can direct and govern his actions. Therefore, the rational creature participates in divine providence not only by being governed but also by governing.

For man to make the best possible use of his freedom, God gives him a tool which is his reason and a manual to enlighten him which is natural law.

Natural law expresses itself in us through inclinations such as the love of truth, obedience to reason, or the famous golden rule: "Do not do unto others what you would not want done unto you." These inclinations are, according to him, innate. Indeed, Saint Thomas writes, "it must be considered that natural justice is that towards which the nature of man inclines."

However, this inner light is not enough to act well. The development of concrete norms of action and their application to specific situations is necessary. It then falls to jurists to define these norms, in accordance with natural law: these are human laws. But natural law is superior to human law and it imposes itself universally, including on Princes.

According to Saint Thomas:

Through the knowledge of natural law, man directly accesses the common order of reason, before and above the political order to which he belongs as a citizen of a particular society. Therefore, there exists a right prior to the formation of the State, a set of general principles that reason can articulate by studying the nature of man as God created it. This right imposes itself on the monarch, on power, which must then respect it. And the laws enacted by political authority are binding only insofar as they conform to natural law.

Reason and faith: an open competition

In the Middle Ages, reason and faith compete for access to truth. Following Abélard and Albert the Great, Thomas Aquinas, in the 13th century, chose to defend the rights of reason and its autonomy in relation to faith.

He borrows from Aristotle's thought the idea of an autonomous natural order, independent of the celestial order. This natural order is indeed transcended by the supernatural order, but it exists separately and is prior to it. Therefore, for him, there are two ways to access the truth about the world and particularly about God:

- On one hand, reason, which starts from nature, from sensible experience, which develops ideas and reaches rational certainties through its reasoning.

- On the other, faith which starts from a Revelation, that is, a sacred text inspired by God. The approach is the opposite, it is not reality or a human characteristic (thought) that leads to certainties but truths given from above by God that will explain reality.

How then to reconcile the two? In the Middle Ages, two traditions of articulating the relationship between reason/faith can be identified: mysticism and religious rationalism.

The rivalry between mysticism and religious rationalism

Mysticism consists of excluding reason from faith. Faith is absolute, beyond reasoning, and should never be subjected to reason. If it contradicts reason, that's normal, and trying to fit revealed truths into the framework of reason is heresy. God is well beyond reason, in other words, there is no point in trying to explain Him. Therefore, philosophy is very poorly regarded. God would even be beyond human language: He would be the unnameable, the wholly Other. His will is absolute and arbitrary. Therefore, one should not seek to understand why God did this or that, obedience is the only appropriate attitude. In Islam, it is also said that one should not represent God or give Him an image. In the Christian world, a mystic like Meister Eckhart notably wrote in a Sermon: "All things have a why, but God has no why." For mystics, the only valid philosophy is the one that comes directly from Revelation. Anything that does not come from it is neither true nor false but devoid of any truth value. The direct opposite of this thought is the one that states that only reason is right, and that all faith is nonsensical. This is absolute rationalism, which leads to atheism. However, such a current did not yet emerge in the Middle Ages.

For proponents of religious rationalism, there is a complementarity between reason and faith: this is the middle position. The truth can be known both by faith and by reason. And so, what is true in faith must also be true in reason, and vice versa. The truth is one but it is accessible in two ways. Therefore, there are two sciences that cannot contradict each other but complement one another: natural science or philosophy and sacred science or theology. If this is not the case, if a contradiction appears between reason and faith, it is either that one reasons poorly, or that one misinterprets the Scriptures.

Thus, for Thomas Aquinas, "Faith is the assent of reason moved by the will in the absence of evidence." In other words, reason is capable of apprehending the world and God, rationally, up to a certain point. At this point, it encounters no more evidence. The will can then choose to believe, and thus go further towards the truth by faith, or not to believe. But faith is not a leap into the absurd, it is not a humiliation of reason.

This is the middle position, which seeks to reconcile faith and reason. True rationalism is not to reject everything that reason does not understand but to think about the limits of reason. What goes beyond reason is not necessarily against reason. A quote from Pascal in the Pensées illustrates this mindset very well: "Two extremes: to exclude reason, to admit only reason."

The Birth of Universities

The Christian Middle Ages were marked, at the beginning of the 13th century, by the birth and multiplicity of universities in the West. A university is a community of students and masters from the same city under the control of the Church and comprising in principle four faculties: arts, theology, law, medicine. Theology is conceived as a science, on the model of Greek science.

In 1200, Philippe-Auguste established the University of Paris, which quickly

became the most renowned university in Europe. In 1257, Robert de Sorbon founded

a college of theology at the University of Paris, which would later be called

the Sorbonne. A new method of teaching and research known as scholasticism (from

schola, school) emerged within these universities. It involved the "disputatio,"

a kind of contradictory debate in front of an audience. A thesis was proposed,

followed by objections to which a response had to be provided. Once all arguments

were exhausted, the master would resolve the debate with a reasoned solution.

In 1200, Philippe-Auguste established the University of Paris, which quickly

became the most renowned university in Europe. In 1257, Robert de Sorbon founded

a college of theology at the University of Paris, which would later be called

the Sorbonne. A new method of teaching and research known as scholasticism (from

schola, school) emerged within these universities. It involved the "disputatio,"

a kind of contradictory debate in front of an audience. A thesis was proposed,

followed by objections to which a response had to be provided. Once all arguments

were exhausted, the master would resolve the debate with a reasoned solution.

Among the great Aristotelian masters who marked this era, we can mention Albert the Great (1200-1280) and Thomas Aquinas (1224-1274). The latter, by establishing reason in its rights, highlighted the specificity and autonomy of philosophical wisdom in relation to theology. Just as grace presupposes nature and fulfills it, faith presupposes and perfects reason.

From then on, religious rationalism would definitively prevail over mysticism.

Religion and Politics: The Birth of the Sovereign State

In the Middle Ages, the Church and Christian monarchies inherited a political model from the Roman Empire, which historians call the theologico-political system, meaning a system where power is sacred, i.e., where the political leader is also a religious leader.

This is why medieval societies are characterized by politico-religious unanimism. Political power bases its legitimacy, authority, and unity on the Christian (or Muslim) faith. It considers itself the guardian of cultural and religious orthodoxy and treats as pariahs those who stray from this unanimity. In this context, even if a certain tolerance could be conceded to those who detach from the common cultural vision (such as Jews), no right to pluralism could be recognized for them. It was not until the end of the Middle Ages, with the conquest of America, that the problem of civil liberties became crucial to the Church and saw the emergence of a first philosophy of law that affirmed and protected individual freedoms, legitimized pluralism, and condemned state coercion.

Saint Augustine and the Theocratic Temptation

The question of the relationship between politics and religion took shape

with Saint Augustine's work Civitas Dei (The City of God).

In it, he explains that two spheres coexist: Two loves have thus made two

cities: the love of self to the contempt of God, the earthly city; the love