name: Theoretical Introduction to the Lightning Network goal: Discover the Lightning Network from a technical perspective objectives:

- Understand the operation of the network's channels.

- Familiarize yourself with the terms HTLC, LNURL, and UTXO.

- Assimilate the management of liquidity and the fees of the LNN.

- Recognize the Lightning Network as a network.

- Understand the theoretical uses of the Lightning Network.

A Journey to Bitcoin's Second Layer

Dive into the heart of the Lightning Network, an essential system for the future of Bitcoin transactions. LNP201 is a theoretical course on the technical workings of Lightning. It unveils the foundations and mechanisms of this second-layer network, designed to make Bitcoin payments fast, economical, and scalable.

Thanks to its network of payment channels, Lightning enables rapid and secure transactions without recording each exchange on the Bitcoin blockchain. Throughout the chapters, you will learn how the opening, management, and closing of channels work, how payments are routed through intermediary nodes securely while minimizing the need for trust, and how to manage liquidity. You will discover what commitment transactions, HTLCs, revocation keys, punishment mechanisms, onion routing, and invoices are.

Whether you are a Bitcoin beginner or more experienced user, this course will provide valuable information to understand and use the Lightning Network. Although we will cover some fundamentals of Bitcoin's operation in the first parts, it is essential to master the basics of Satoshi's invention before diving into LNP201.

Enjoy your discovery!

Introduction

Course Overview

Welcome to the LNP201 course!

This training aims to provide you with an in-depth technical understanding of the Lightning Network, an overlay network designed to facilitate fast and often low-cost Bitcoin transactions. You will gradually discover the fundamental concepts that govern this system, from opening payment channels to routing techniques and liquidity management.

Section 1: Fundamentals

We will start with a general introduction to the Lightning Network, establishing

essential foundations about Bitcoin, its addresses, UTXOs, and how transactions

work. This fundamental review is necessary to understand how the Lightning Network

relies on the underlying blockchain mechanisms to operate securely.

Section 2: Opening and Closing Channels

In this section, we will explore the channel opening process, which is the cornerstone

of the Lightning Network. You will learn how commitment transactions are created,

the role of revocation keys for security, and how channels can be closed either

collaboratively or unilaterally. Each step will be explained precisely and technically

to help you grasp all the subtleties.

Section 3: A Liquidity Network

The Lightning Network is not limited to individual channels; it is a real payment

network. We will see how transactions can be routed through intermediary nodes

using HTLCs. This section will also introduce you to the challenges of inbound

and outbound liquidity.

Section 4: Lightning Network Tools

This section presents practical tools of the Lightning Network, such as Invoices, LNURL, and Keysend. You will also learn

how to manage your channels' liquidity, an essential aspect to ensure smooth

payments and maximize the efficiency of your transactions on Lightning.

Section 5: Going Further

Finally, we will conclude the training by recapping the concepts covered and

paving the way for more advanced topics for those who wish to deepen their knowledge

of the Lightning Network.

Ready to uncover the technical mechanisms of the Lightning Network? Let’s dive in!

The Fundamentals

Understanding the Lightning Network

The Lightning Network is a network of payment channels built on top of the Bitcoin protocol, aiming to enable fast and low-cost transactions. It allows the creation of payment channels between participants, within which transactions can be made almost instantly and with minimal fees, without having to record each transaction individually on the blockchain. Thus, the Lightning Network seeks to improve Bitcoin's scalability and make it usable for low-value payments.

Before exploring the "network" aspect, it is important to understand the concept of a payment channel on Lightning, how it works, and its specifics. This is the subject of this first chapter.

The Concept of Payment Channel

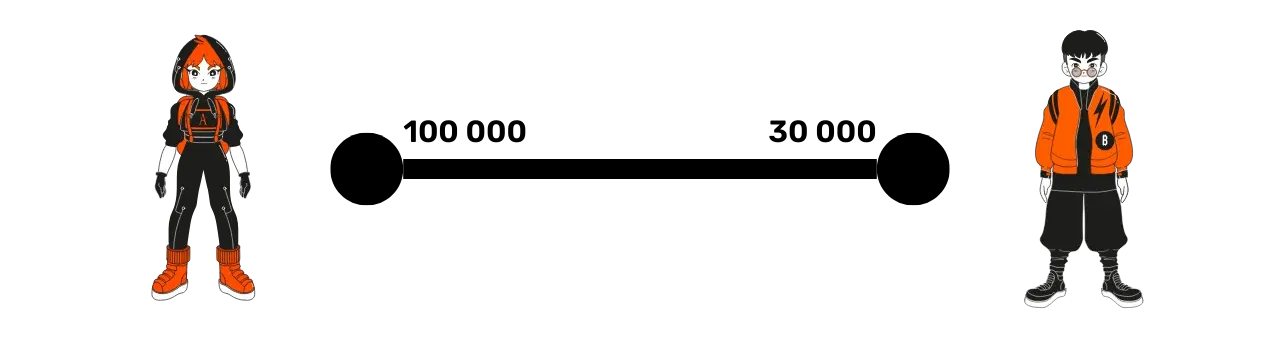

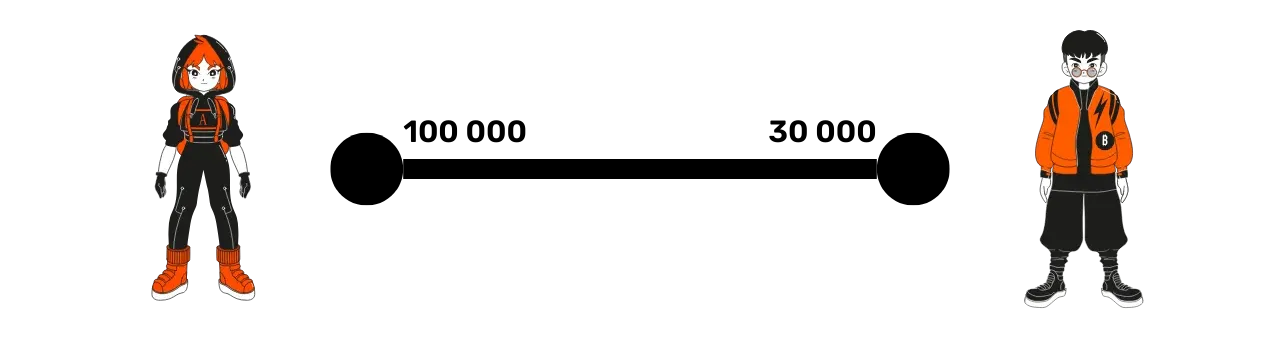

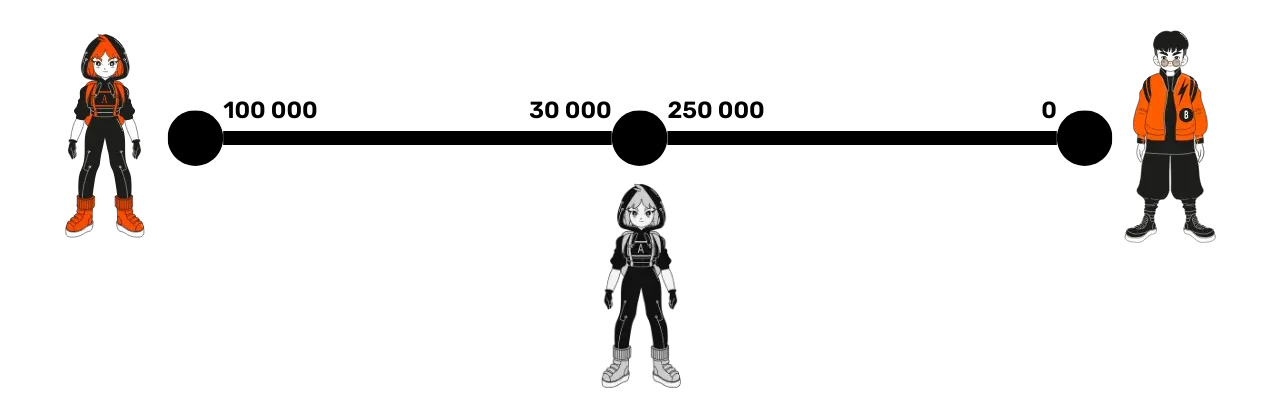

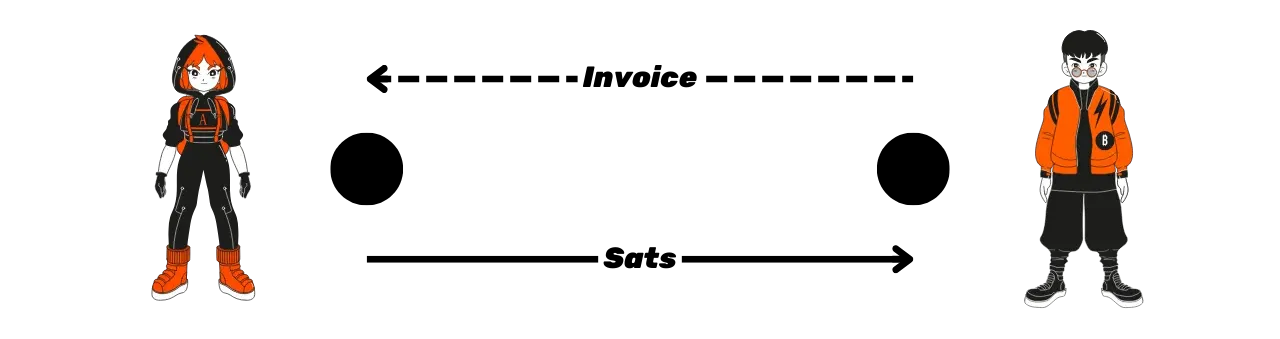

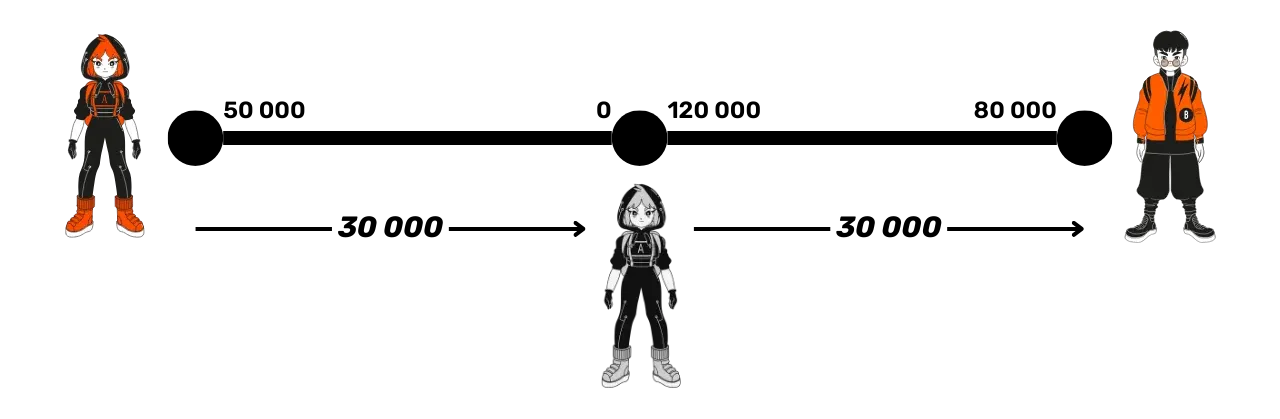

A payment channel allows two parties, here Alice and Bob, to exchange funds over the Lightning Network. Each protagonist has a node, symbolized by a circle, and the channel between them is represented by a line segment.

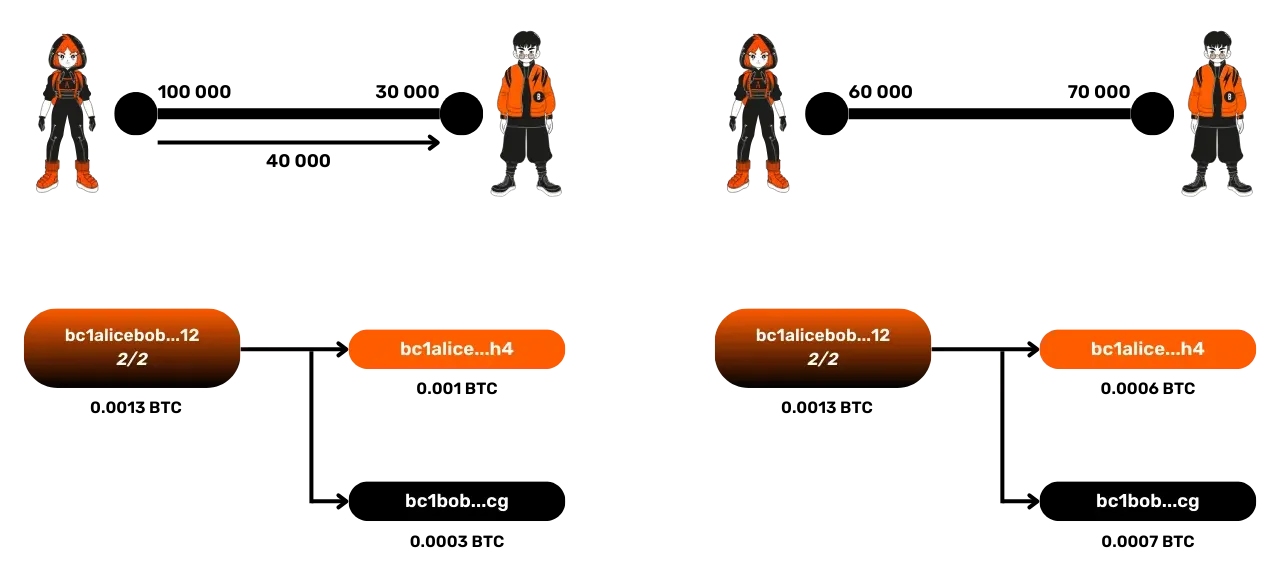

In our example, Alice has 100,000 satoshis on her side of the channel, and Bob has 30,000, for a total of 130,000 satoshis, which constitutes the channel capacity.

But what is a satoshi?

The satoshi (or "sat") is a unit of account on Bitcoin. Similar to a cent for the euro, a satoshi is simply a fraction of Bitcoin. One satoshi is equal to 0.00000001 Bitcoin, or one hundred millionth of a Bitcoin. Using the satoshi becomes increasingly practical as the value of Bitcoin rises.

The Allocation of Funds in the Channel

Let's return to the payment channel. The key concept here is the "side of the channel". Each participant has funds on their side of the channel: Alice 100,000 satoshis and Bob 30,000. As we've seen, the sum of these funds represents the total capacity of the channel, a figure set when it is opened.

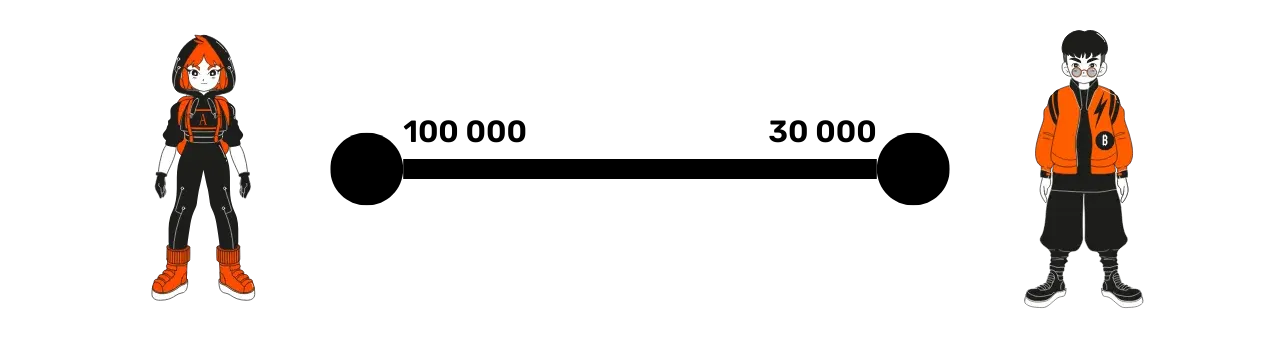

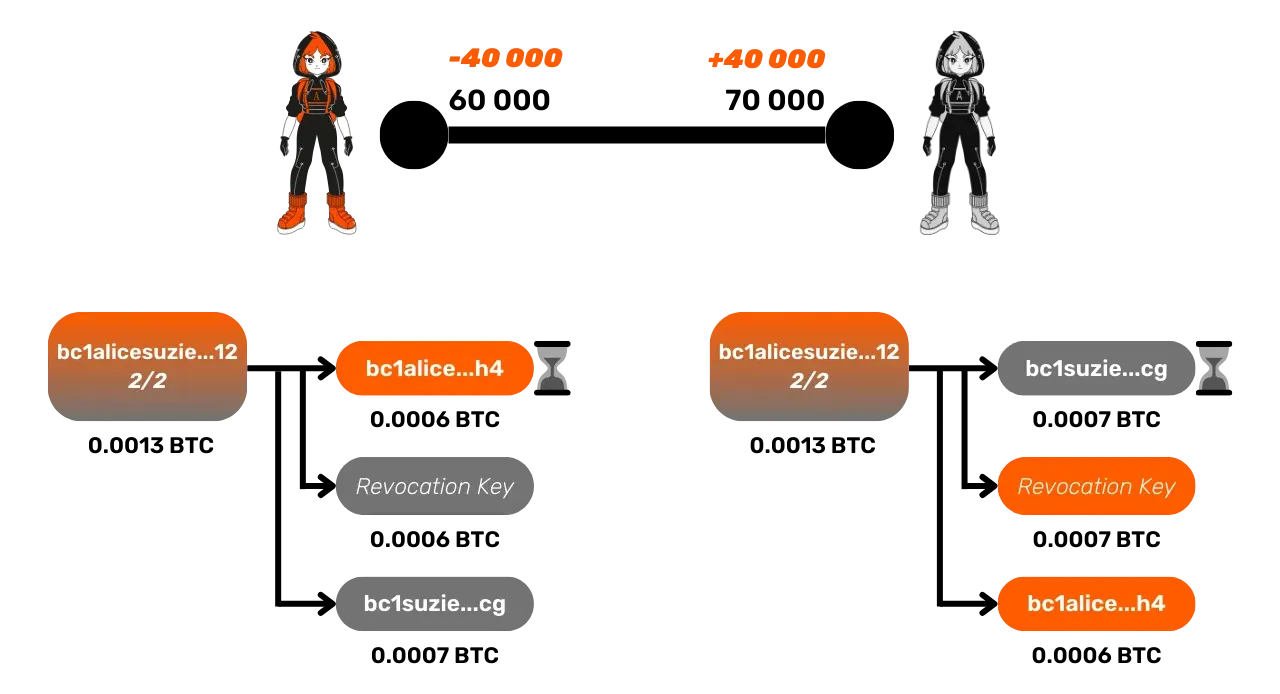

Let's take an example of a Lightning transaction. If Alice wants to send 40,000 satoshis to Bob, this is possible because she has enough funds (100,000 satoshis). After this transaction, Alice will have 60,000 satoshis on her side and Bob 70,000.

The channel capacity, at 130,000 satoshis, remains constant. What changes is the allocation of funds. This system does not allow sending more funds than one possesses. For example, if Bob wanted to send back 80,000 satoshis to Alice, he could not, because he only has 70,000.

Another way to imagine the allocation of funds is to think of a slider that indicates where the funds are in the channel. Initially, with 100,000 satoshis for Alice and 30,000 for Bob, the slider is logically on Alice's side. After the transaction of 40,000 satoshis, the slider will move slightly towards Bob's side, who now has 70,000 satoshis.

This representation can be useful for imagining the balance of funds in a channel.

The Fundamental Rules of a Payment Channel

The first point to remember is that the channel capacity is fixed. It's somewhat like the diameter of a pipe: it determines the maximum amount of funds that can be sent through the channel at once. Let's take an example: if Alice has 130,000 satoshis on her side, she can only send a maximum of 130,000 satoshis to Bob in a single transaction. However, Bob can then send these funds back to Alice, either partially or in full.

What's important to understand is that the fixed capacity of the channel limits the maximum amount of a single transaction, but not the total number of possible transactions, nor the overall volume of funds exchanged within the channel.

What should you take away from this chapter?

- The capacity of a channel is fixed and determines the maximum amount that can be sent in a single transaction.

- The funds in a channel are distributed between the two participants, and each can only send to the other the funds they own on their side.

- The Lightning Network thus allows for the rapid and efficient exchange of funds, while respecting the limitations imposed by the capacity of the channels.

This is the end of this first chapter, where we have laid the groundwork for the Lightning Network. In the coming chapters, we will see how to open a channel and delve deeper into the concepts discussed here.

Bitcoin, Addresses, UTXO, and Transactions

This chapter is a bit special since it will not be directly dedicated to Lightning, but to Bitcoin. Indeed, the Lightning Network is a layer on top of Bitcoin. It is therefore essential to understand certain fundamental concepts of Bitcoin to properly grasp the functioning of Lightning in the subsequent chapters. In this chapter, we will review the basics of Bitcoin receiving addresses, UTXOs, as well as the functioning of Bitcoin transactions.

Bitcoin Addresses, Private Keys, and Public Keys

A Bitcoin address is a series of characters derived from a public key, which is itself calculated from a private key. As you surely know, it is used to lock bitcoins, which is equivalent to receiving them in our wallet.

The private key is a secret element that should never be shared, while the public key and the address can be shared without security risk (their disclosure only represents a risk to your privacy). Here is a common representation that we will adopt throughout this training:

- The private keys will be represented vertically.

- The public keys will be represented horizontally.

- Their color indicates who possesses them (Alice in orange and Bob in black...).

Bitcoin Transactions: Sending Funds and Scripts

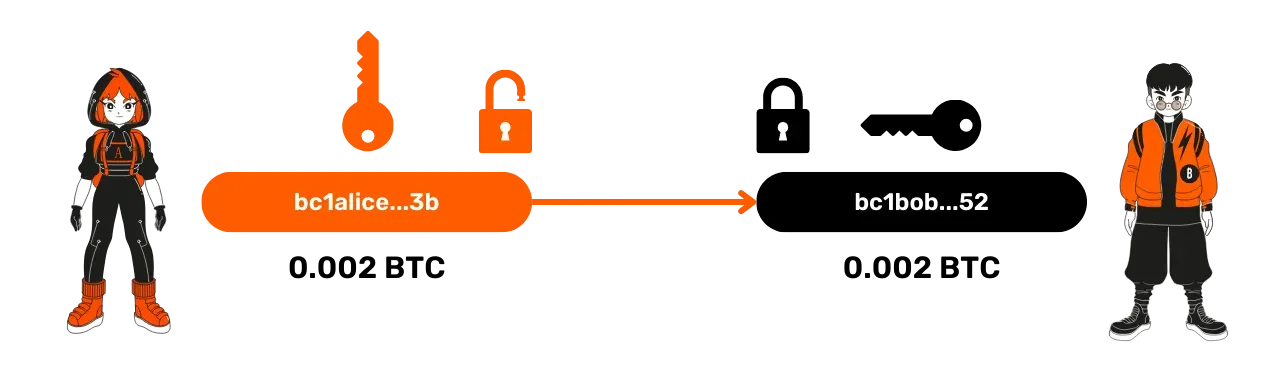

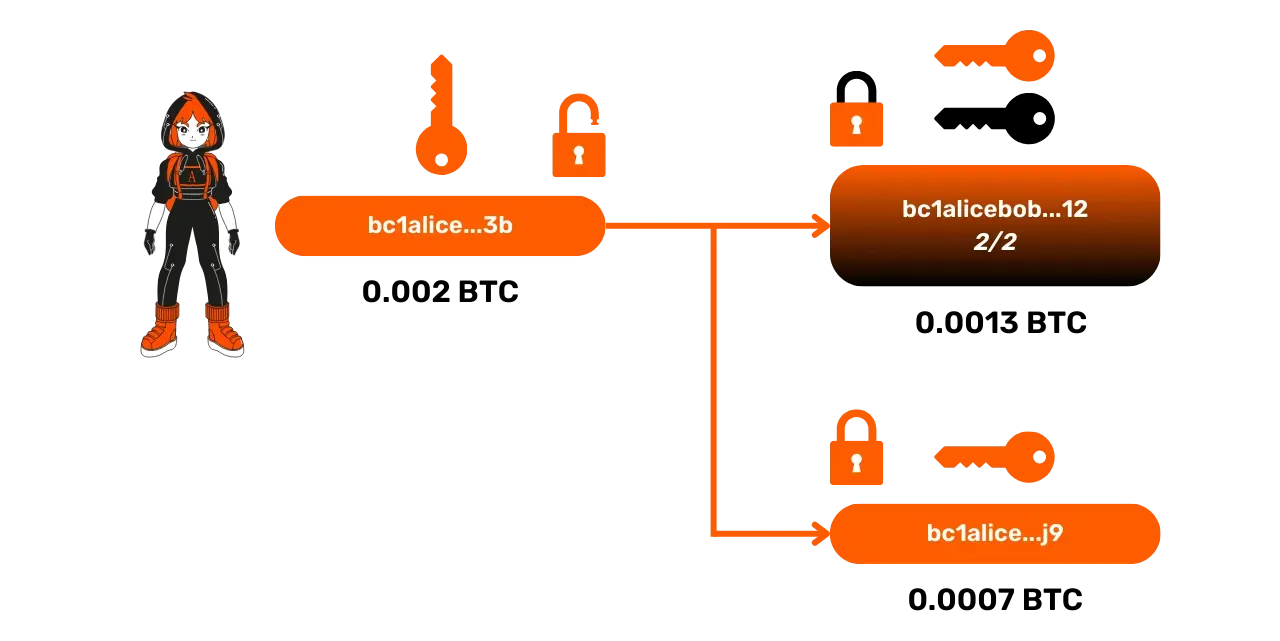

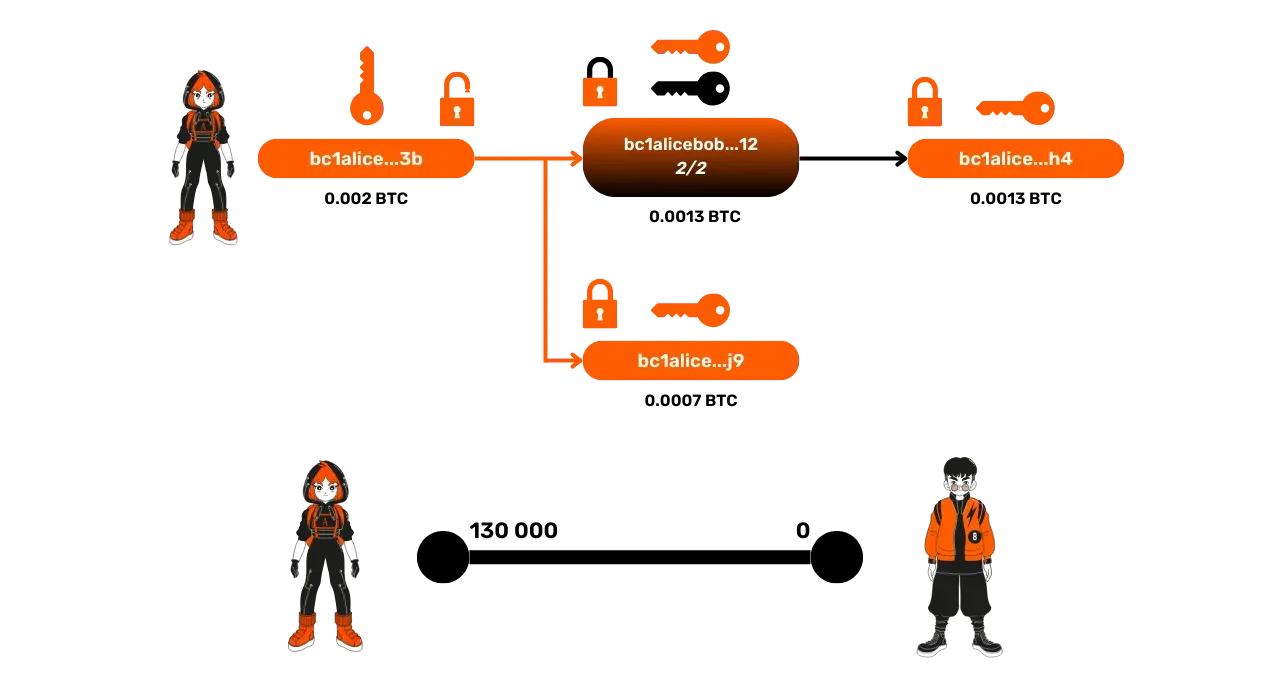

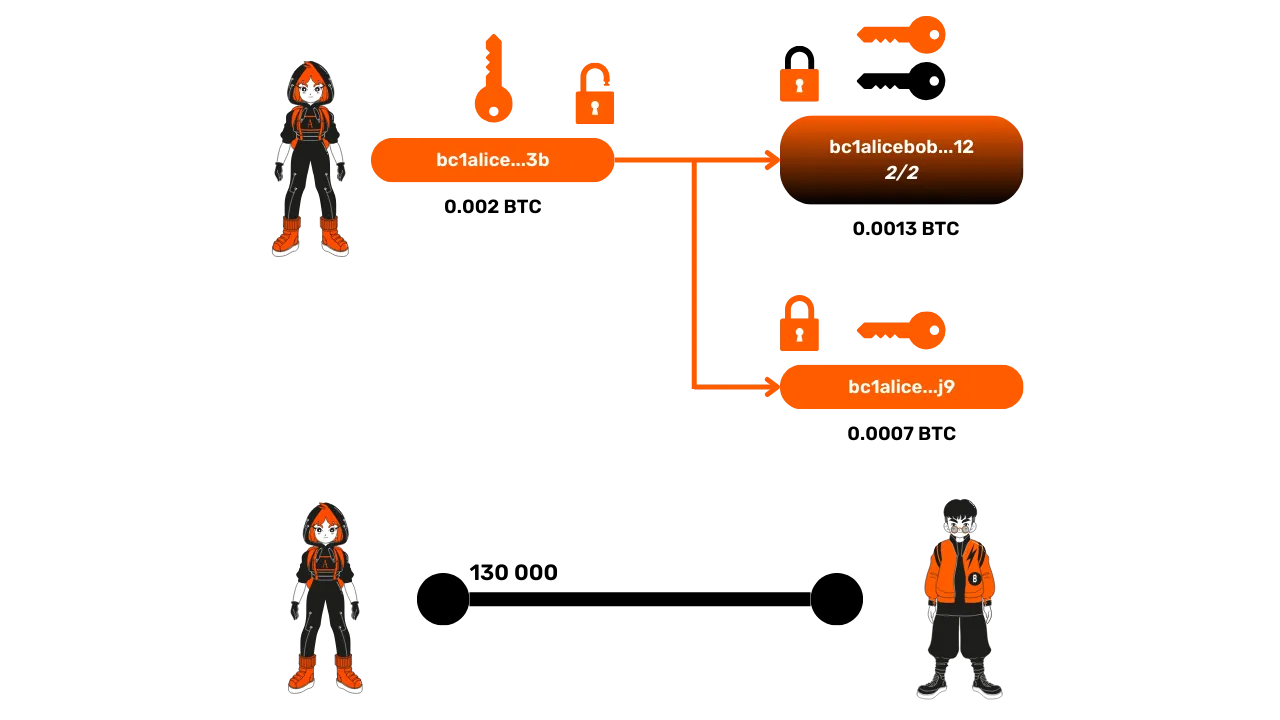

On Bitcoin, a transaction involves sending funds from one address to another. Let's take the example of Alice sending 0.002 Bitcoin to Bob. Alice uses the private key associated with her address to sign the transaction, thereby proving that she is indeed able to spend these funds. But what exactly happens behind this transaction? The funds on a Bitcoin address are locked by a script, a kind of mini-program that imposes certain conditions to spend the funds.

The most common script requires a signature with the private key associated with the address. When Alice signs a transaction with her private key, she unlocks the script that blocks the funds, and they can then be transferred. The transfer of funds involves adding a new script to these funds, stipulating that to spend them this time, Bob's private key signature will be required.

UTXOs: Unspent Transaction Outputs

On Bitcoin, what we actually exchange are not directly bitcoins, but UTXOs (Unspent Transaction Outputs), meaning "unspent transaction outputs".

A UTXO is a piece of bitcoin that can be of any value, for example, 2,000 bitcoins, 8 bitcoins, or even 8,000 sats. Each UTXO is locked by a script, and to spend it, one must satisfy the script's conditions, often a signature with the private key corresponding to a given receiving address.

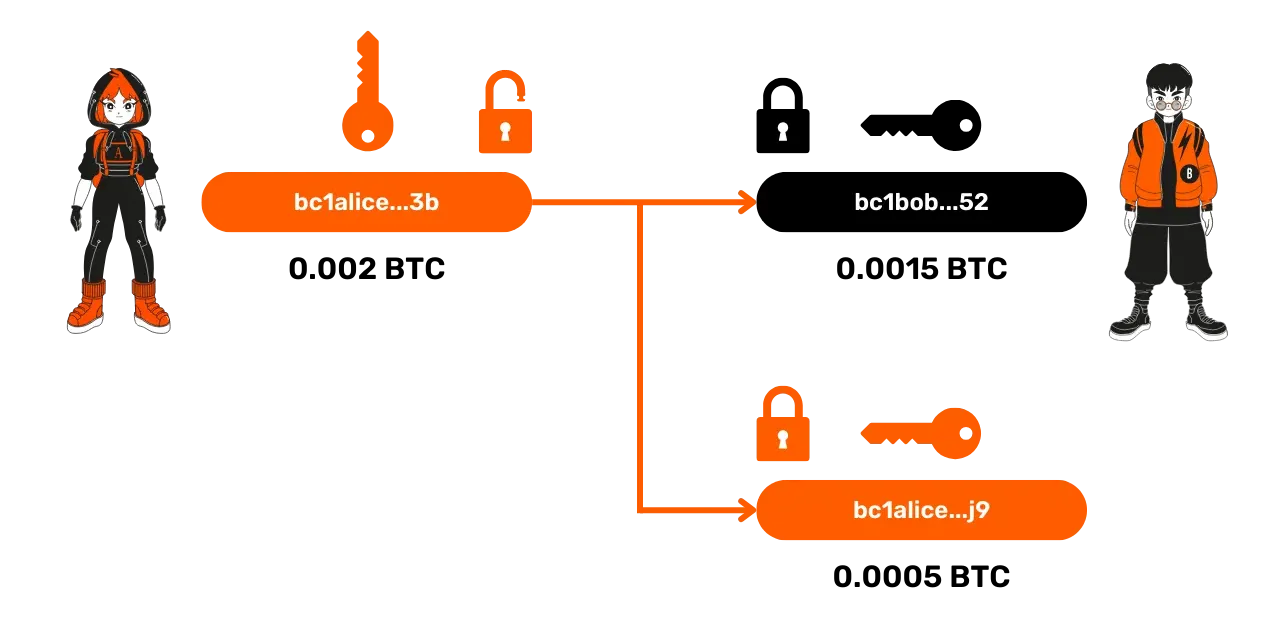

UTXOs cannot be divided. Each time they are used to spend the amount in bitcoins they represent, it must be done in its entirety. It's a bit like a banknote: if you have a €10 bill and you owe the baker €5, you can't just cut the bill in half. You have to give him the €10 bill, and he will give you €5 in change. This is exactly the same principle for UTXOs on Bitcoin! For example, when Alice unlocks a script with her private key, she unlocks the entire UTXO. If she wishes to send only a part of the funds represented by this UTXO to Bob, she can "fragment" it into several smaller ones. She will then send 0.0015 BTC to Bob and send the remainder, 0.0005 BTC, to a change address.

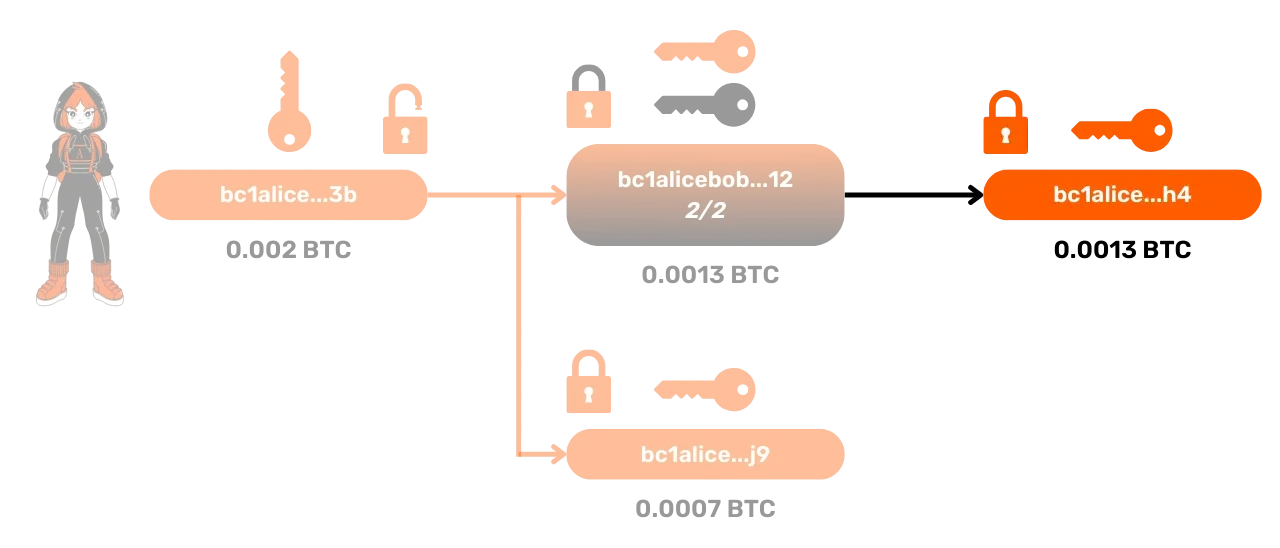

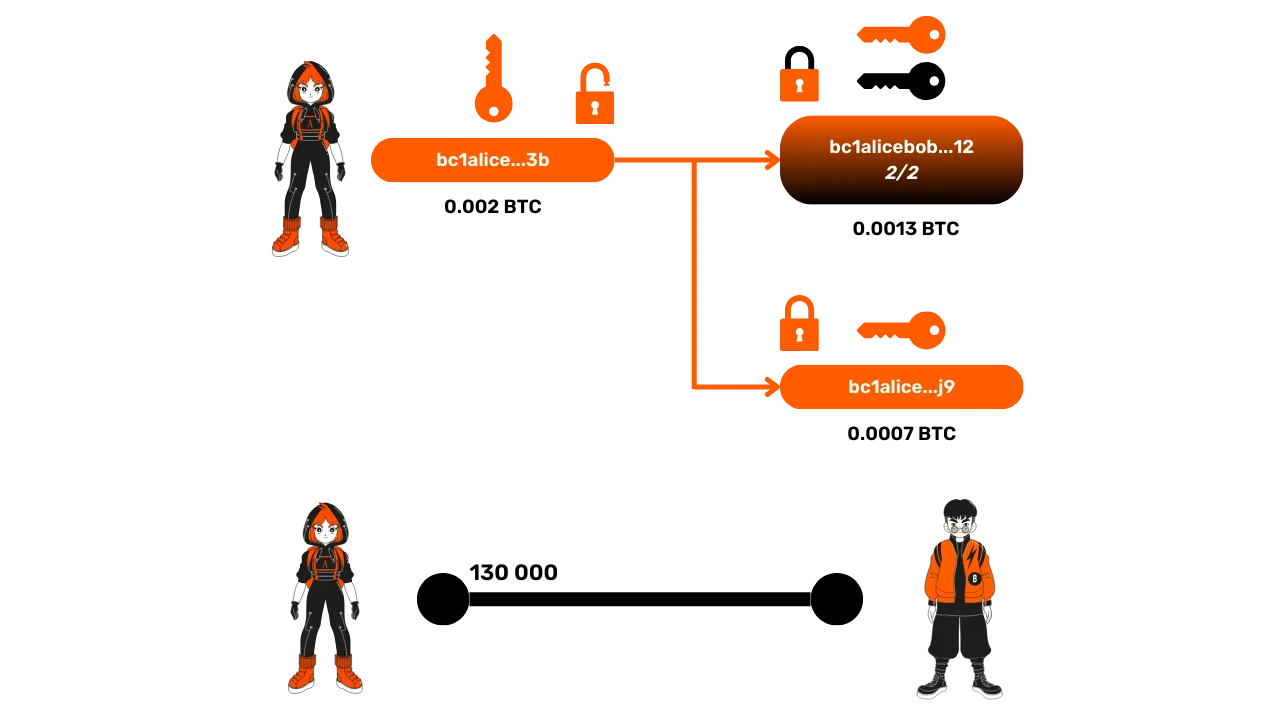

Here is an example of a transaction with 2 outputs:

- A UTXO of 0.0015 BTC for Bob, locked by a script requiring Bob's private key signature.

- A UTXO of 0.0005 BTC for Alice, locked by a script requiring her own signature.

Multi-signature Addresses

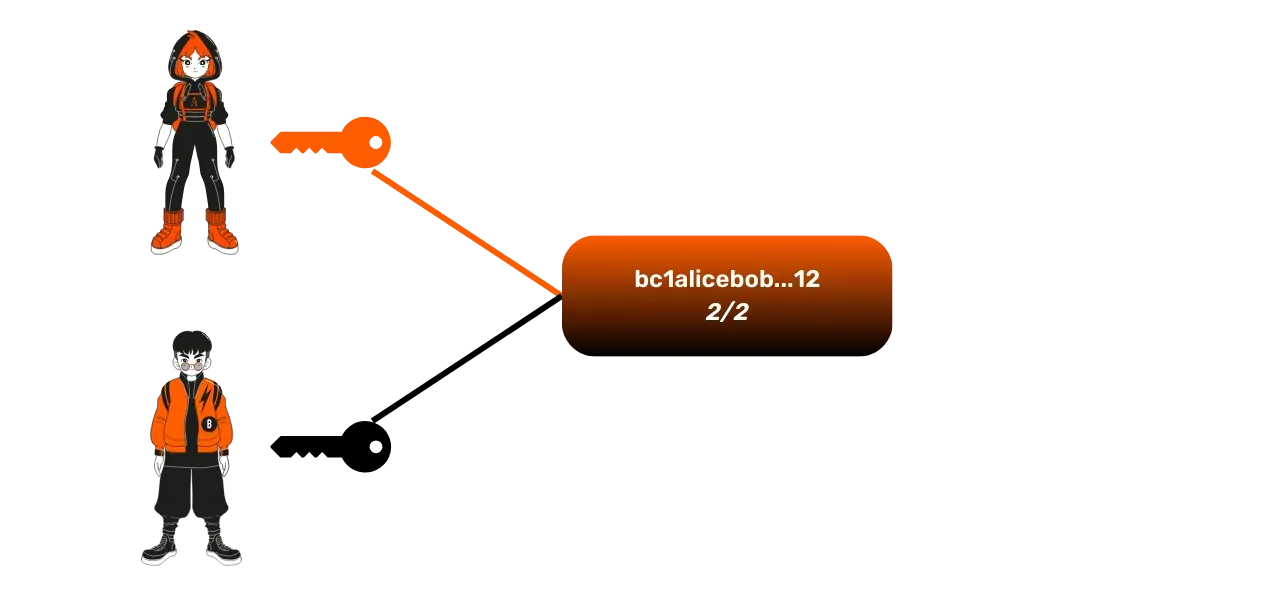

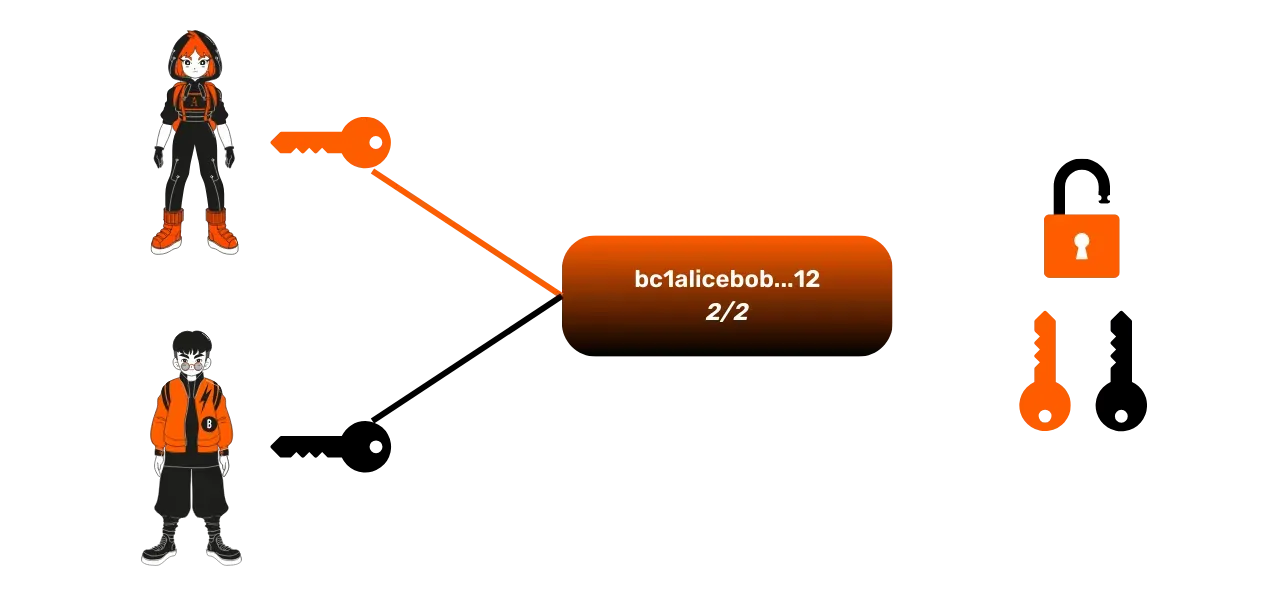

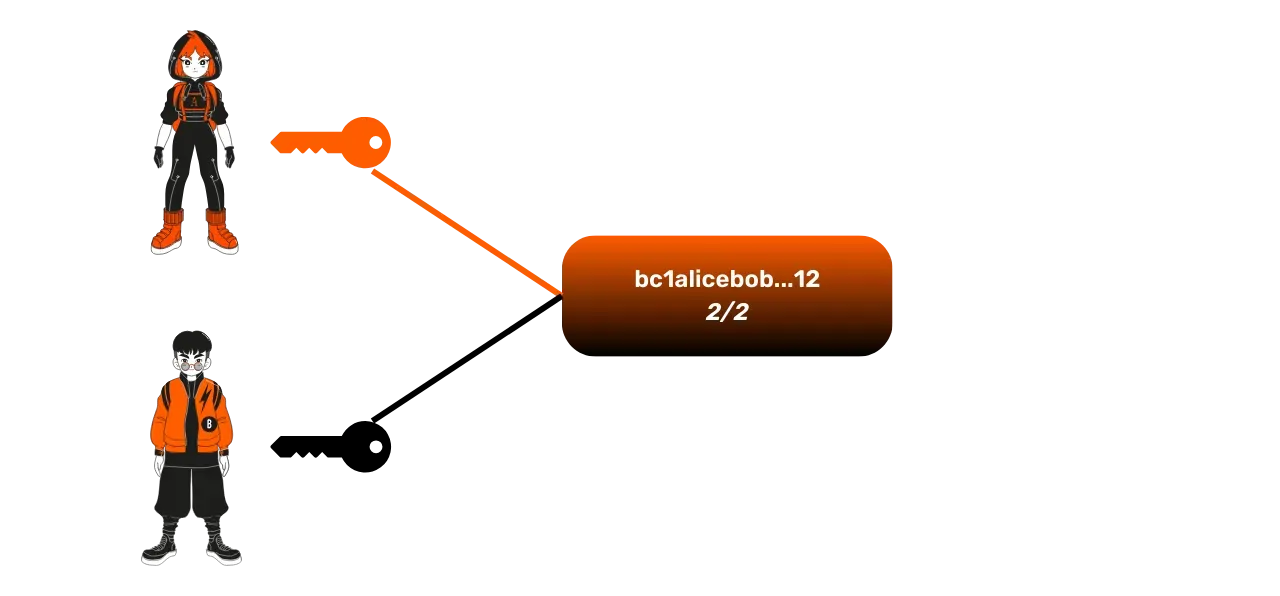

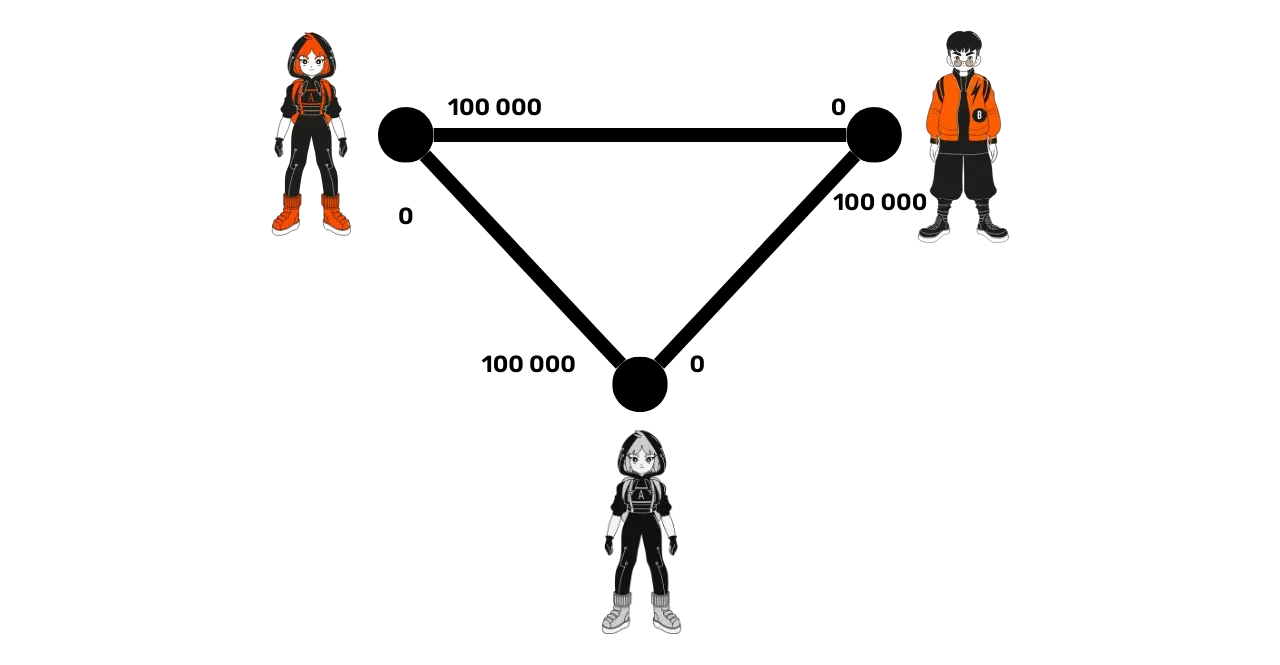

In addition to simple addresses generated from a single public key, it is possible to create multi-signature addresses from multiple public keys. A particularly interesting case for the Lightning Network is the 2/2 multi-signature address, generated from two public keys:

To spend the funds locked with this 2/2 multi-signature address, it is necessary to sign with the two private keys associated with the public keys.

This type of address is precisely the representation on the Bitcoin blockchain of payment channels on the Lightning Network.

What should you take away from this chapter?

- A Bitcoin address is derived from a public key, which is itself derived from a private key.

- Funds on Bitcoin are locked by scripts, and to spend these funds, one must satisfy the script, which generally involves providing a signature with the corresponding private key.

- UTXOs are pieces of bitcoins locked by scripts, and each transaction on Bitcoin consists of unlocking a UTXO and then creating one or more new ones in return.

- 2/2 multi-signature addresses require the signature of two private keys to spend the funds. These specific addresses are used in the context of Lightning to create payment channels.

This chapter on Bitcoin has allowed us to review some essential notions for what follows. In the next chapter, we will specifically discover how the opening of channels on the Lightning Network works.

Opening and Closing Channels

Channel Opening

In this chapter, we will see more precisely how to open a payment channel on the Lightning Network and understand the link between this operation and the underlying Bitcoin system.

Lightning Channels

As we saw in the first chapter, a payment channel on Lightning can be compared to a "pipe" for exchanging funds between two participants (Alice and Bob in our examples). The capacity of this channel corresponds to the sum of the available funds on each side. In our example, Alice has 100,000 satoshis and Bob has 30,000 satoshis, giving a total capacity of 130,000 satoshis.

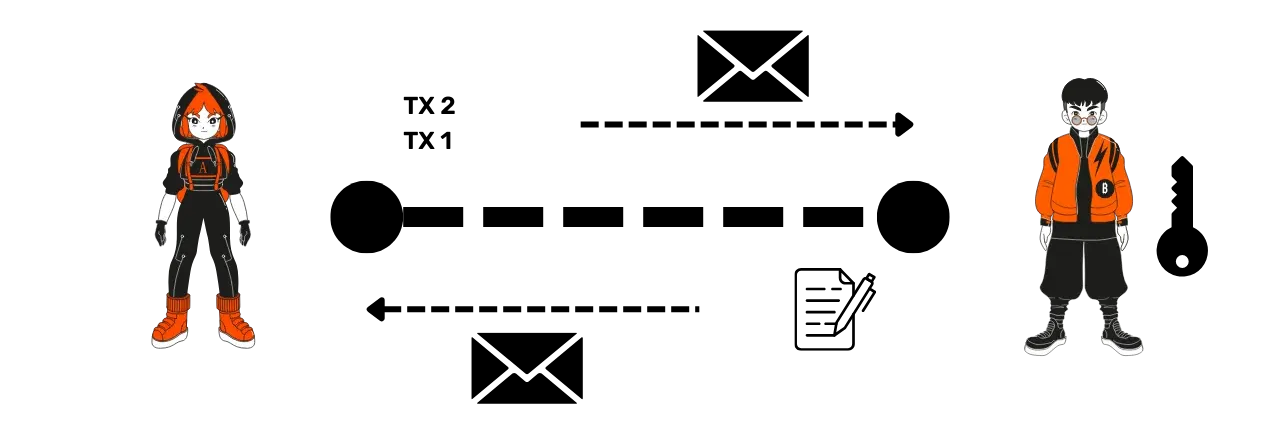

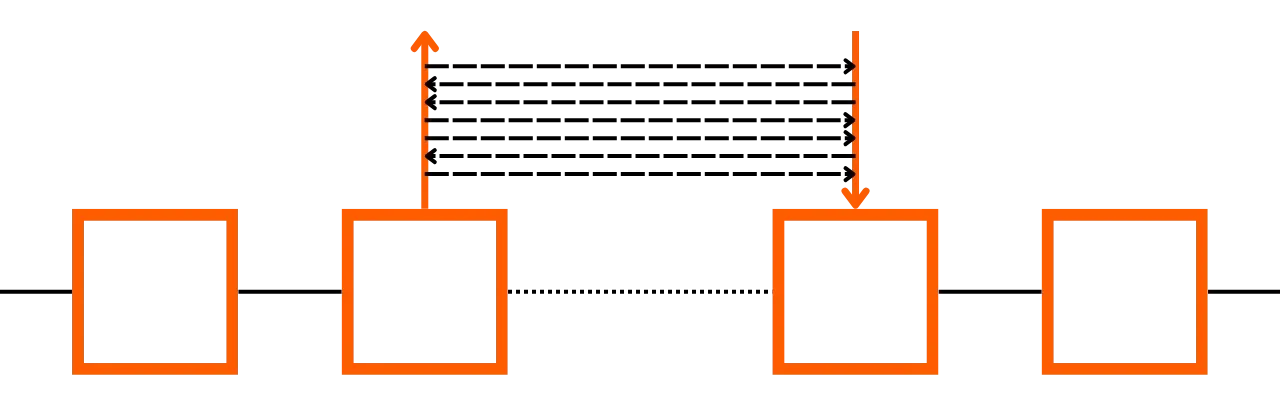

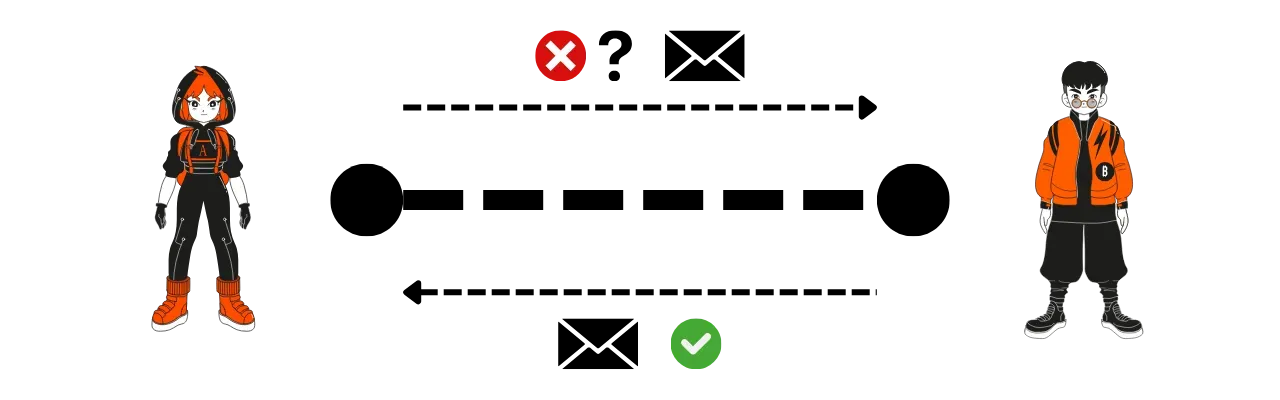

Levels of Information Exchange

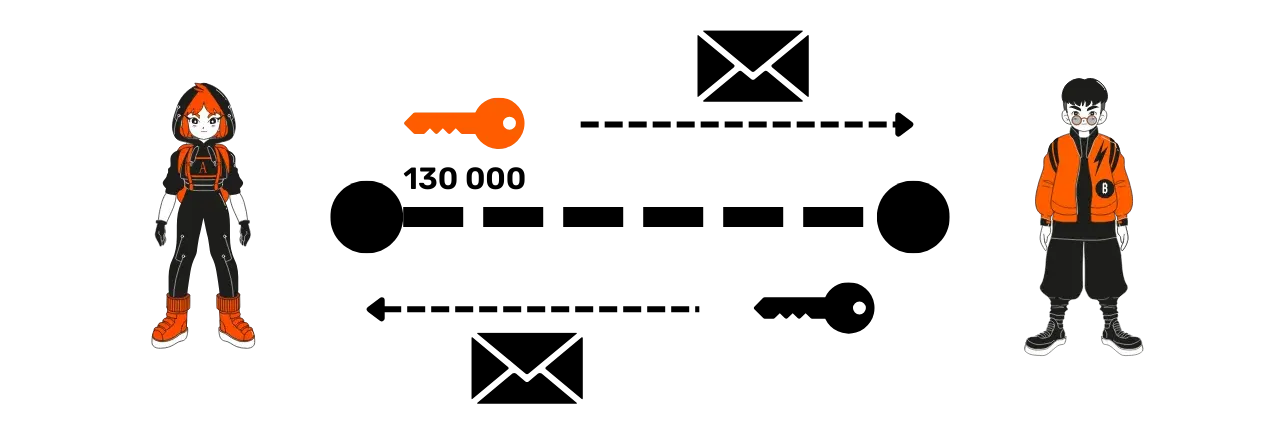

It's crucial to clearly distinguish the different levels of exchange on the Lightning Network:

- Peer-to-peer communications (Lightning protocol): These are the messages that Lightning nodes send to each other to communicate. We will represent these messages with dashed black lines in our diagrams.

- Payment channels (Lightning protocol): These are the paths for exchanging funds on Lightning, which we will represent with solid black lines.

- Bitcoin transactions (Bitcoin protocol): These are the transactions made onchain, which we will represent with orange lines.

It's worth noting that a Lightning node can communicate via the P2P protocol without opening a channel, but to exchange funds, a channel is necessary.

Steps to Open a Lightning Channel

- Message exchange: Alice wants to open a channel with Bob. She sends him a message containing the amount she wants to deposit in the channel (130,000 sats) and her public key. Bob responds by sharing his own public key.

- Creation of the multisignature address: With these two public keys, Alice creates a 2/2 multisignature address, meaning that the funds that will later be deposited on this address will require both signatures (Alice and Bob) to be spent.

- Deposit transaction: Alice prepares a Bitcoin transaction to deposit funds on this multisignature address. For example, she may decide to send 130,000 satoshis to this multisignature address. This transaction is constructed but not yet published on the blockchain.

- Withdrawal transaction: Before publishing the deposit transaction, Alice constructs a withdrawal transaction so she can recover her funds in case of a problem with Bob. Indeed, once Alice publishes the deposit transaction, her sats will be locked on a 2/2 multisignature address which requires both her signature and Bob's signature to be unlocked. Alice protects against this loss risk by constructing the withdrawal transaction that allows her to recover her funds.

- Bob's signature: Alice sends the deposit transaction to Bob as proof and asks him to sign the withdrawal transaction. Once Bob's signature is obtained on the withdrawal transaction, Alice is assured of being able to recover her funds at any time, as only her own signature is now needed to unlock the multisignature.

- Publication of the deposit transaction: Once Bob's signature is obtained, Alice can publish the deposit transaction on the Bitcoin blockchain, thereby officially opening the Lightning channel between the two users.

When is the channel open?

The channel is considered open once the deposit transaction is included in a Bitcoin block and it has reached a certain depth of confirmations (number of following blocks).

What should you remember from this chapter?

- Opening a channel starts with the exchange of messages between the two parties (exchange of amounts and public keys).

- A channel is formed by creating a 2/2 multisignature address and depositing funds into it via a Bitcoin transaction.

- The person opening the channel ensures they can recover their funds through a withdrawal transaction signed by the other party before publishing the deposit transaction.

In the next chapter, we will explore the technical workings of a Lightning transaction within a channel.

Commitment Transaction

In this chapter, we will discover the technical functioning of a transaction within a channel on the Lightning Network, that is, when funds are moved from one side of the channel to the other.

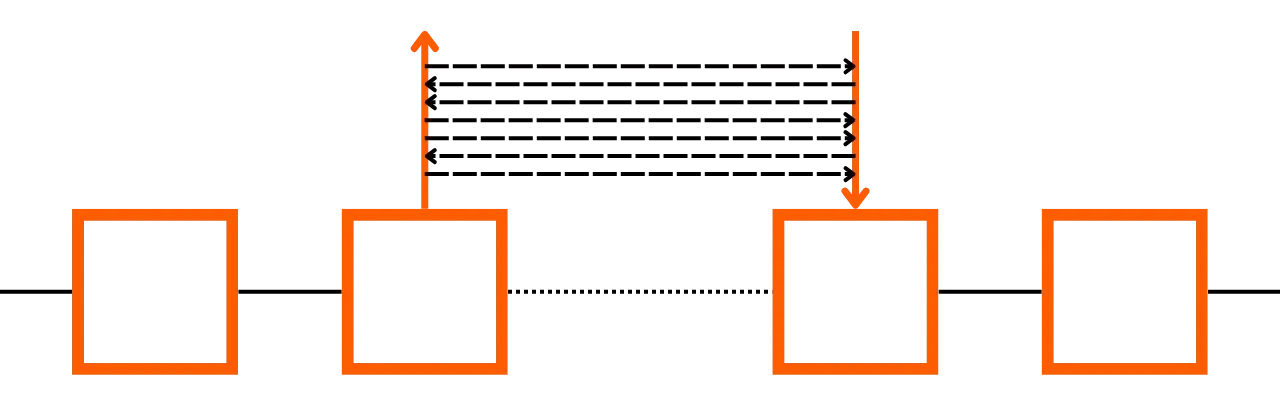

Reminder of the channel lifecycle

As seen previously, a Lightning channel begins with an opening via a Bitcoin transaction. The channel can be closed at any time, also via a Bitcoin transaction. Between these two moments, an almost infinite number of transactions can be performed within the channel, without going through the Bitcoin blockchain. Let's see what happens during a transaction in the channel.

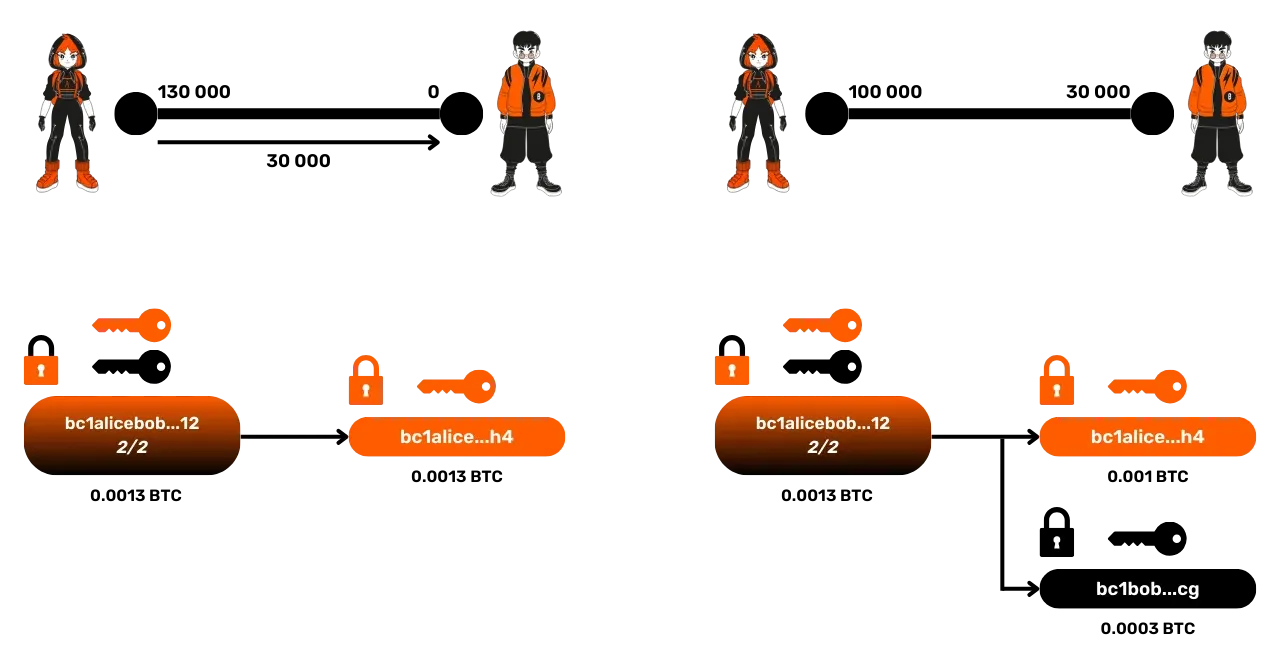

The initial state of the channel

At the time of opening the channel, Alice deposited 130,000 satoshis on the multisignature address of the channel. Thus, in the initial state, all the funds are on Alice's side. Before opening the channel, Alice also had Bob sign a withdrawal transaction, which would allow her to recover her funds if she wished to close the channel.

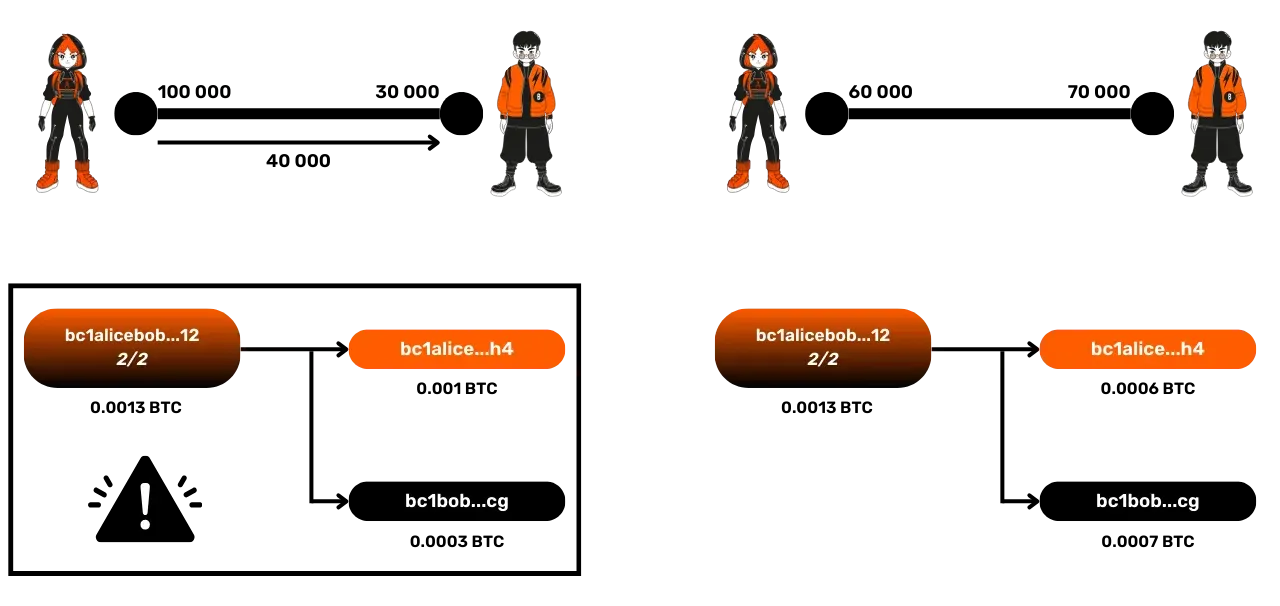

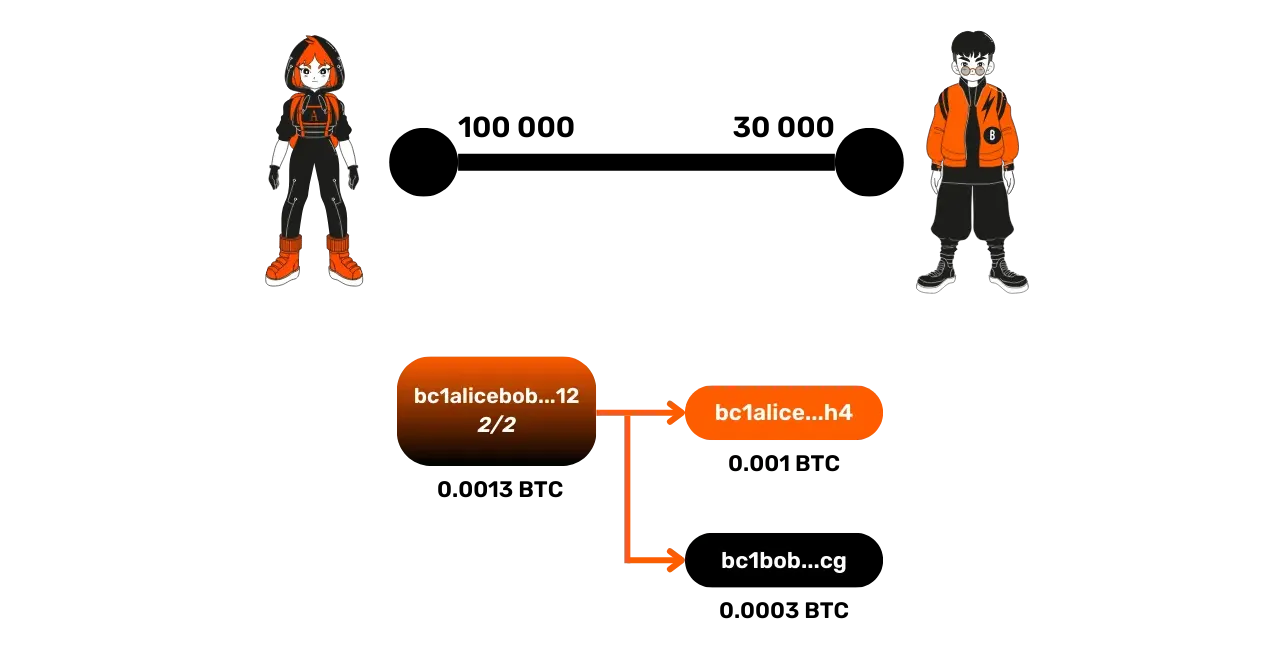

Unpublished Transactions: The Commitment Transactions

When Alice makes a transaction in the channel to send funds to Bob, a new Bitcoin transaction is created to reflect this change in the distribution of funds. This transaction, called a commitment transaction, is not published on the blockchain but represents the new state of the channel following the Lightning transaction.

Let's take an example with Alice sending 30,000 satoshis to Bob:

- Initially: Alice has 130,000 satoshis.

- After the transaction: Alice has 100,000 satoshis, and

Bob 30,000 satoshis. To validate this transfer, Alice and Bob create a new unpublished Bitcoin transaction that would send 100,000 satoshis to Alice and 30,000 satoshis to Bob from the multisignature address. Both parties construct this transaction

independently, but with the same data (amounts and addresses). Once

constructed, each signs the transaction and exchanges their signature with

the other. This allows either party to publish the transaction at any time

if necessary to recover their share of the channel on the main Bitcoin

blockchain.

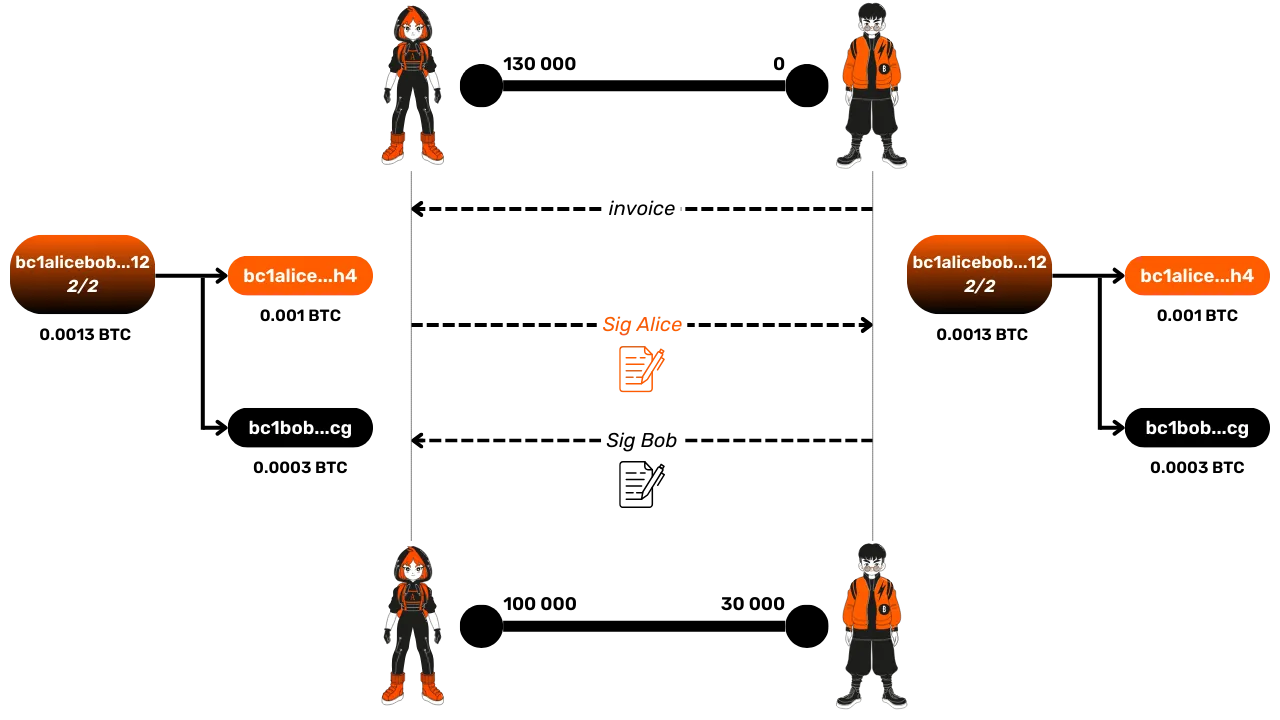

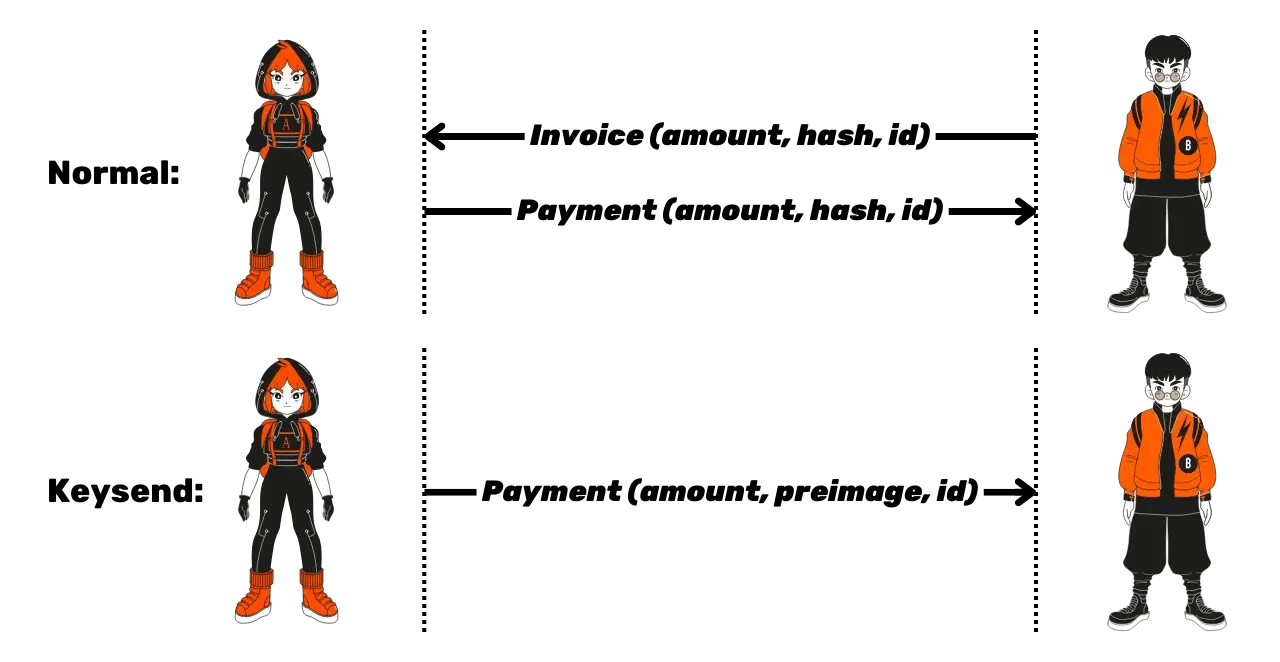

Transfer Process: The Invoice

When Bob wants to receive funds, he sends Alice an invoice for 30,000 satoshis. Alice then proceeds to pay this invoice by starting the transfer within the channel. As we have seen, this process relies on the creation and signing of a new commitment transaction.

Each commitment transaction represents the new distribution of funds in the channel after the transfer. In this example, after the transaction, Bob has 30,000 satoshis and Alice has 100,000 satoshis. If either of the two participants decided to publish this commitment transaction on the blockchain, it would result in the closing of the channel and the funds would be distributed according to this last distribution.

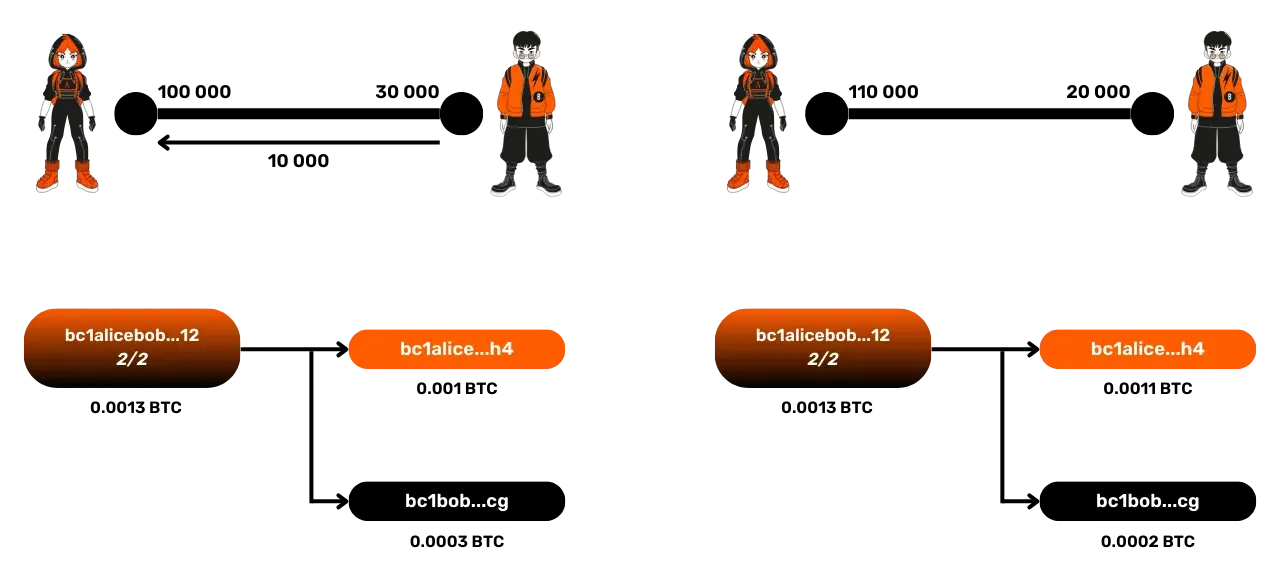

New State After a Second Transaction

Let's take another example: after the first transaction where Alice sent 30,000 satoshis to Bob, Bob decides to send 10,000 satoshis back to Alice. This creates a new state of the channel. The new commitment transaction will represent this updated distribution:

- Alice now has 110,000 satoshis.

- Bob has 20,000 satoshis.

Again, this transaction is not published on the blockchain but can be at any time in case the channel is closed.

In summary, when funds are transferred within a Lightning channel:

- Alice and Bob create a new commitment transaction, which reflects the new distribution of funds.

- This Bitcoin transaction is signed by both parties, but not published on the Bitcoin blockchain as long as the channel remains open.

- The commitment transactions ensure that each participant can recover their funds at any time on the Bitcoin blockchain by publishing the last signed transaction.

However, this system has a potential flaw, which we will address in the next chapter. We will see how each participant can protect themselves against an attempt to cheat by the other party.

Revocation Key

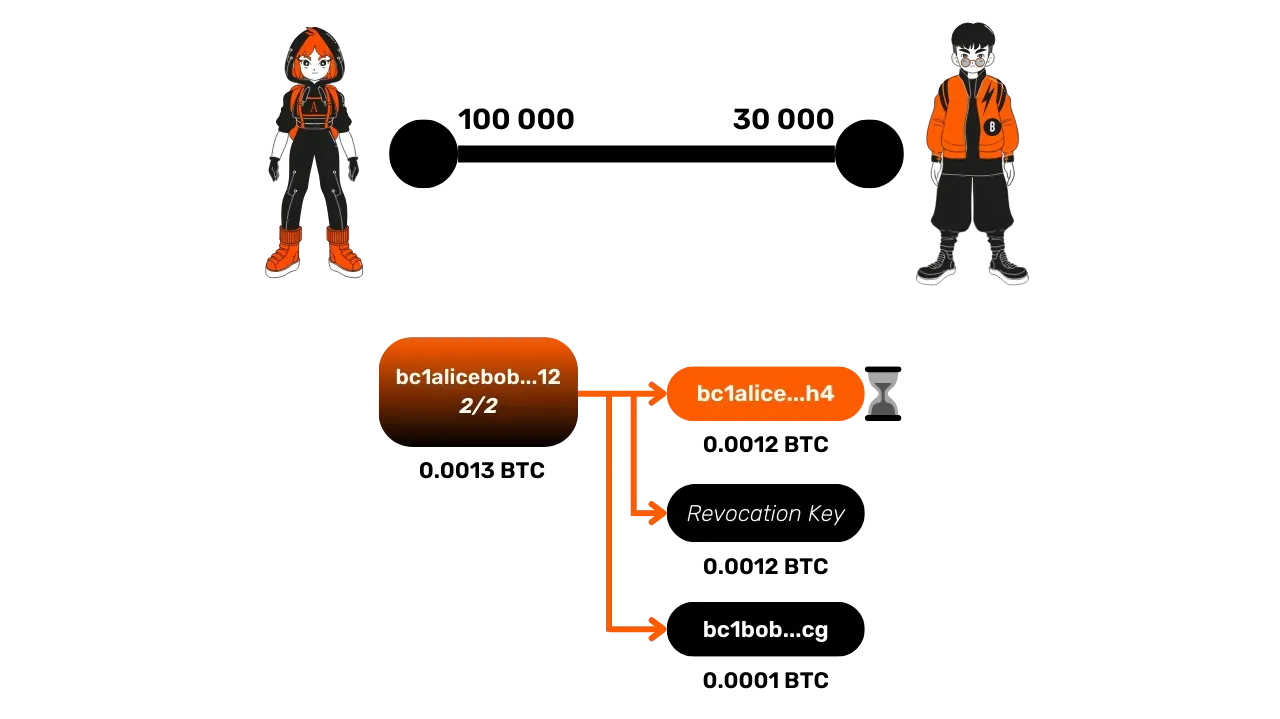

f2f61e5b-badb-5947-9a81-7aa530b44e59 :::video id=1d850f23-eff1-4725-b284-ce12456a2c26::: In this chapter, we will delve deeper into how transactions work on the Lightning Network by discussing the mechanisms in place to protect against cheating, ensuring that each party adheres to the rules within a channel.

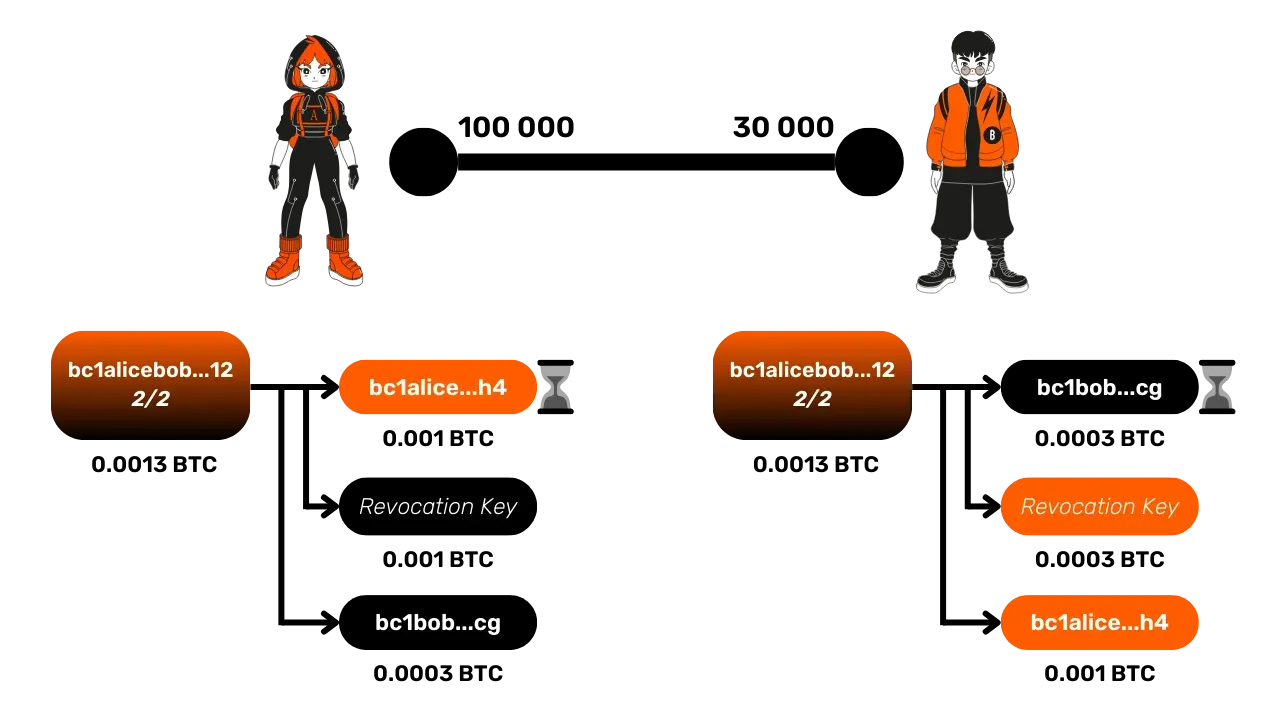

Reminder: Commitment Transactions

As previously seen, transactions on Lightning rely on unpublished commitment transactions. These transactions reflect the current distribution of funds in the channel. When a new Lightning transaction is made, a new commitment transaction is created and signed by both parties to reflect the new state of the channel.

Let's take a simple example:

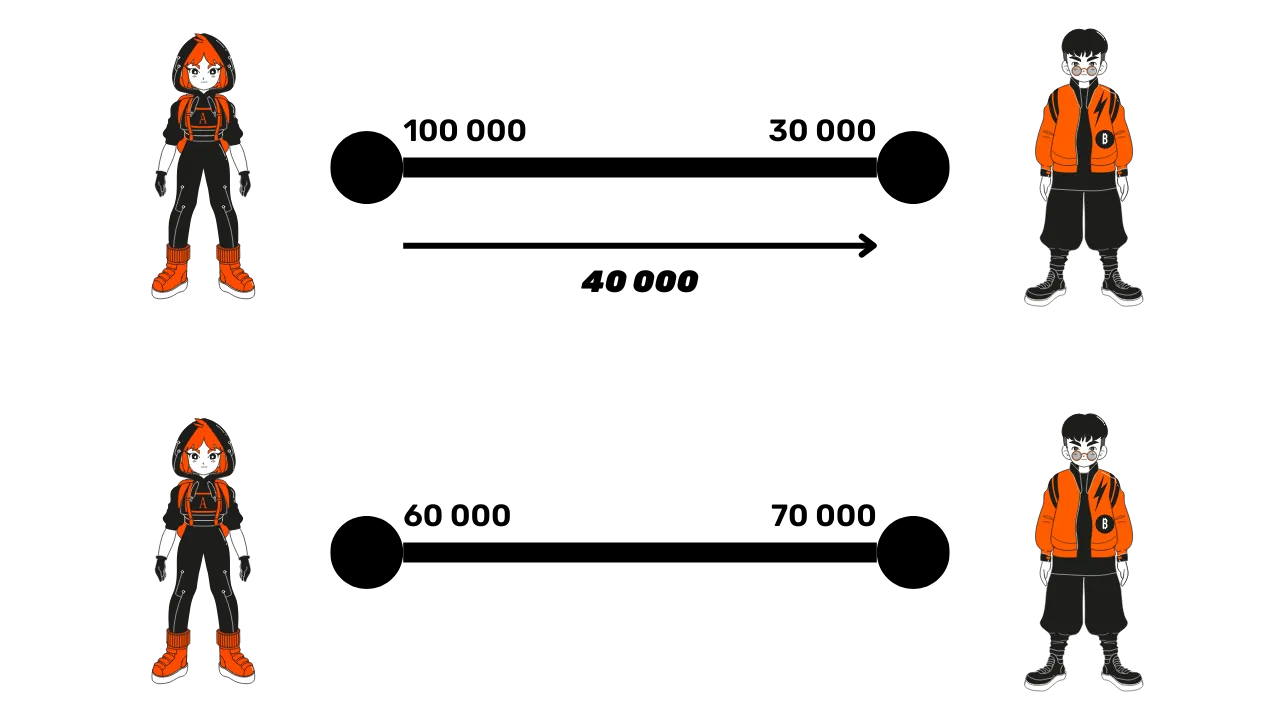

- Initial state: Alice has 100,000 satoshis, Bob 30,000 satoshis.

- After a transaction where Alice sends 40,000 satoshis to

Bob, the new commitment transaction distributes the funds as follows:

- Alice: 60,000 satoshis

- Bob: 70,000 satoshis

At any time, both parties can publish the latest commitment transaction signed to close the channel and recover their funds.

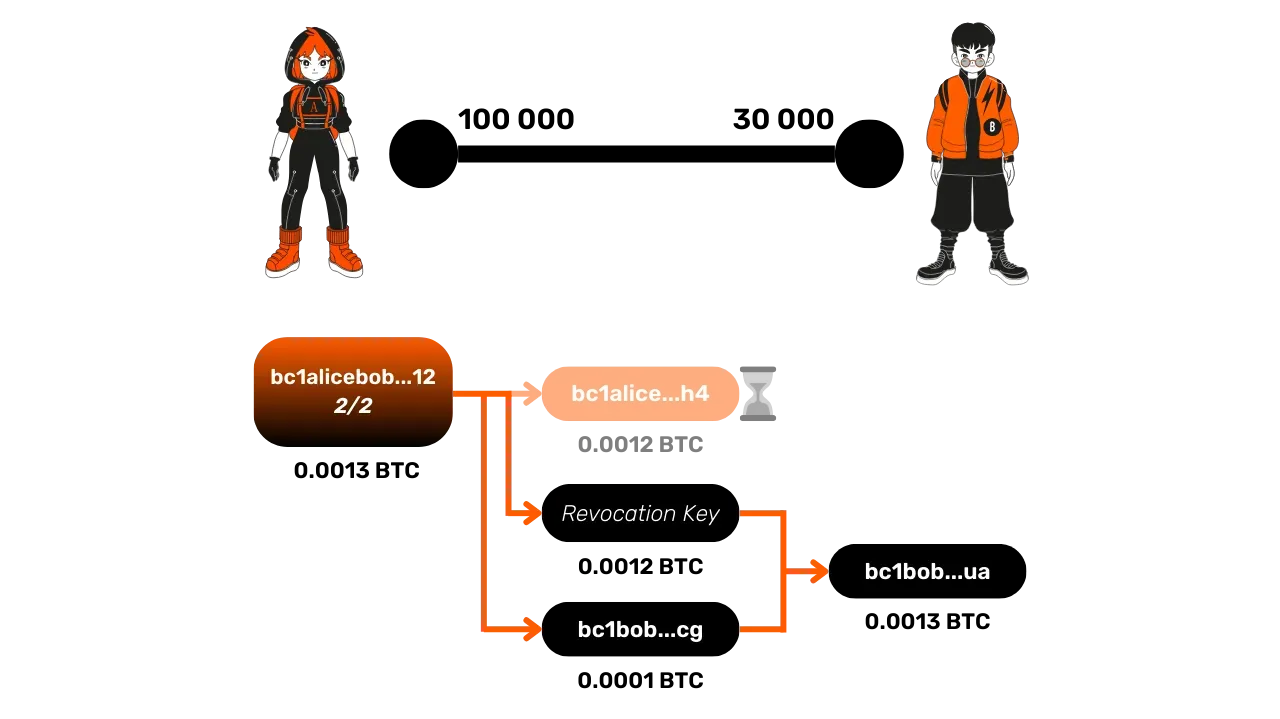

The Flaw: Cheating by Publishing an Old Transaction

A potential problem arises if one of the parties decides to cheat by publishing an old commitment transaction. For example, Alice could publish an older commitment transaction where she had 100,000 satoshis, even though she now only has 60,000 in reality. This would allow her to steal 40,000 satoshis from Bob.

Even worse, Alice could publish the very first withdrawal transaction, the one before the channel was opened, where she had 130,000 satoshis, and thus steal the entire channel's funds.

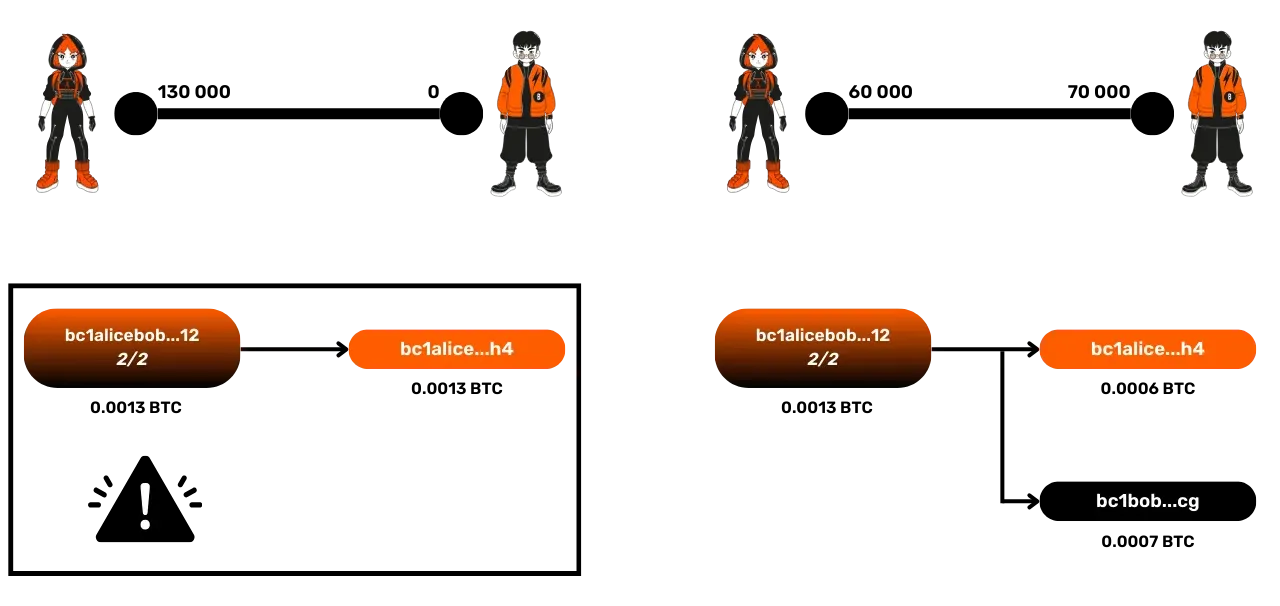

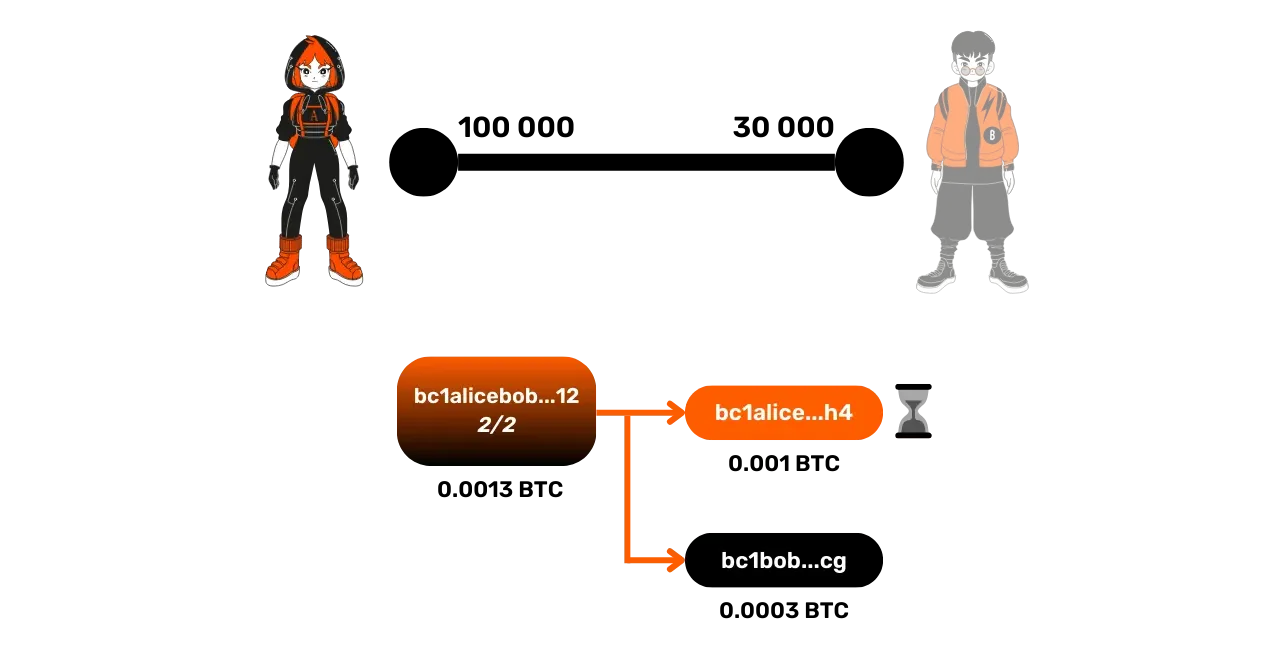

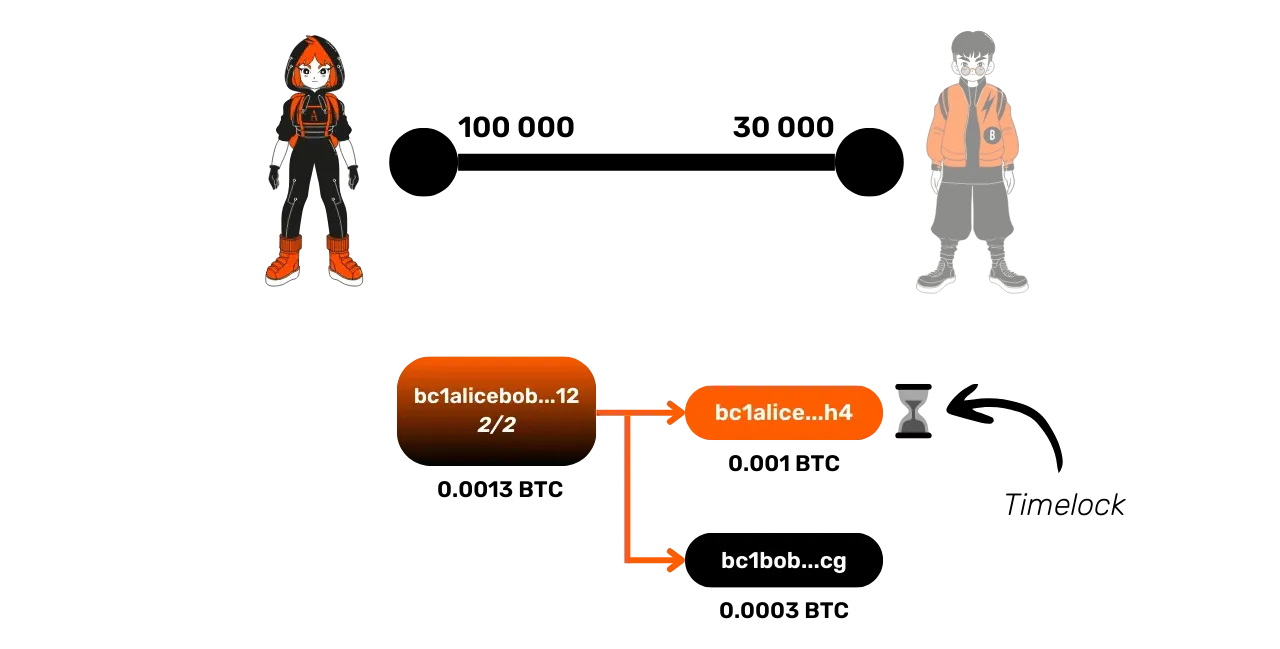

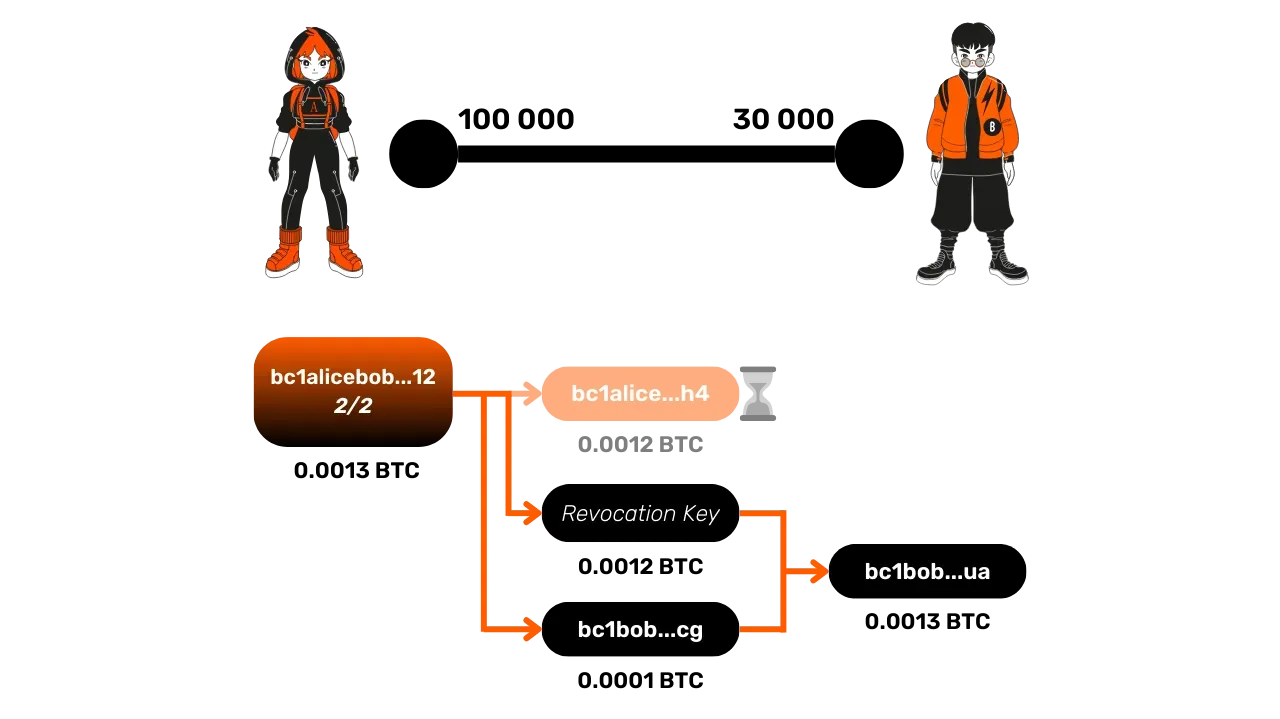

Solution: Revocation Key and Timelock

To prevent this kind of cheating by Alice, on the Lightning Network, security mechanisms are added to the commitment transactions:

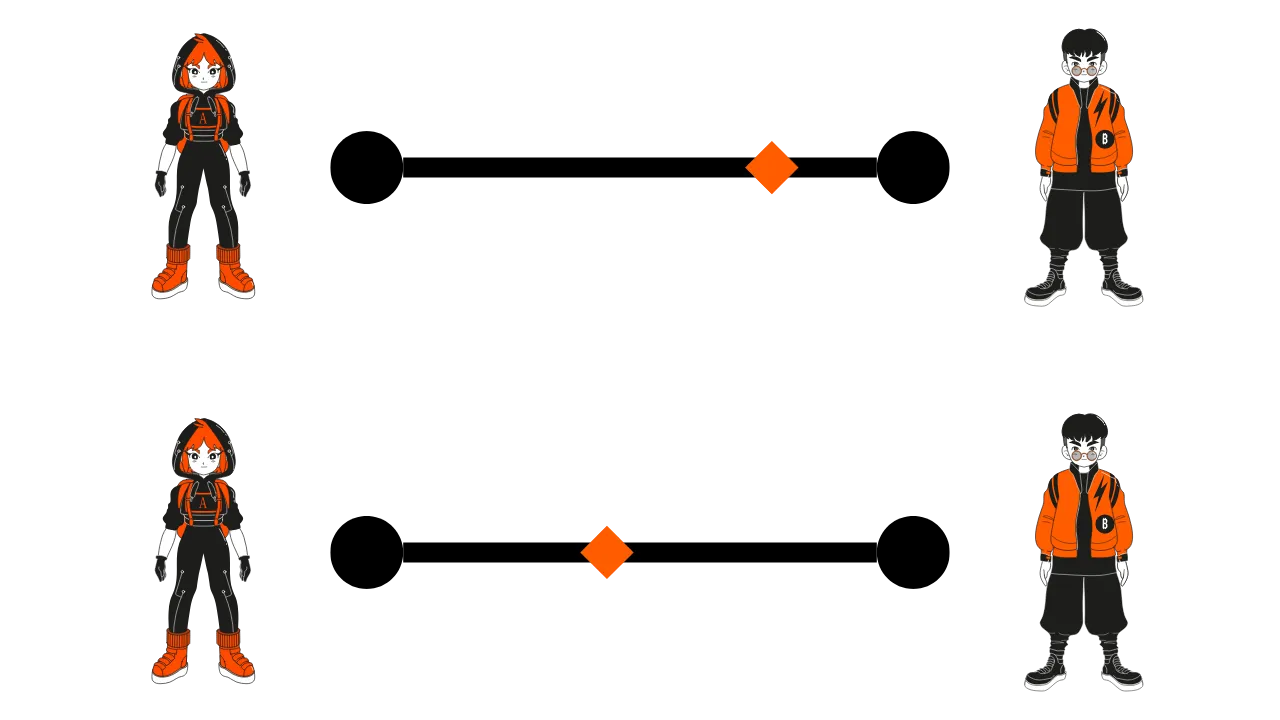

- The timelock: Each commitment transaction includes a timelock for Alice's funds. The timelock is a smart contract primitive that sets a time condition that must be met for a transaction to be added to a block. This means that Alice cannot recover her funds until a certain number of blocks have passed if she publishes one of the commitment transactions. This timelock starts to apply from the confirmation of the commitment transaction. Its duration is generally proportional to the size of the channel, but it can also be manually configured.

- Revocation Key: Alice's funds can also be immediately spent by Bob if he possesses the revocation key. This key consists of a secret held by Alice and a secret held by Bob. Note that this secret is different for each commitment transaction. Thanks to these 2 combined mechanisms, Bob has the time to detect Alice's attempt to cheat, and to punish her by retrieving his output with the revocation key, which for Bob means recovering all the funds of the channel. Our new commitment transaction will now look like this:

Let's detail the functioning of this mechanism together.

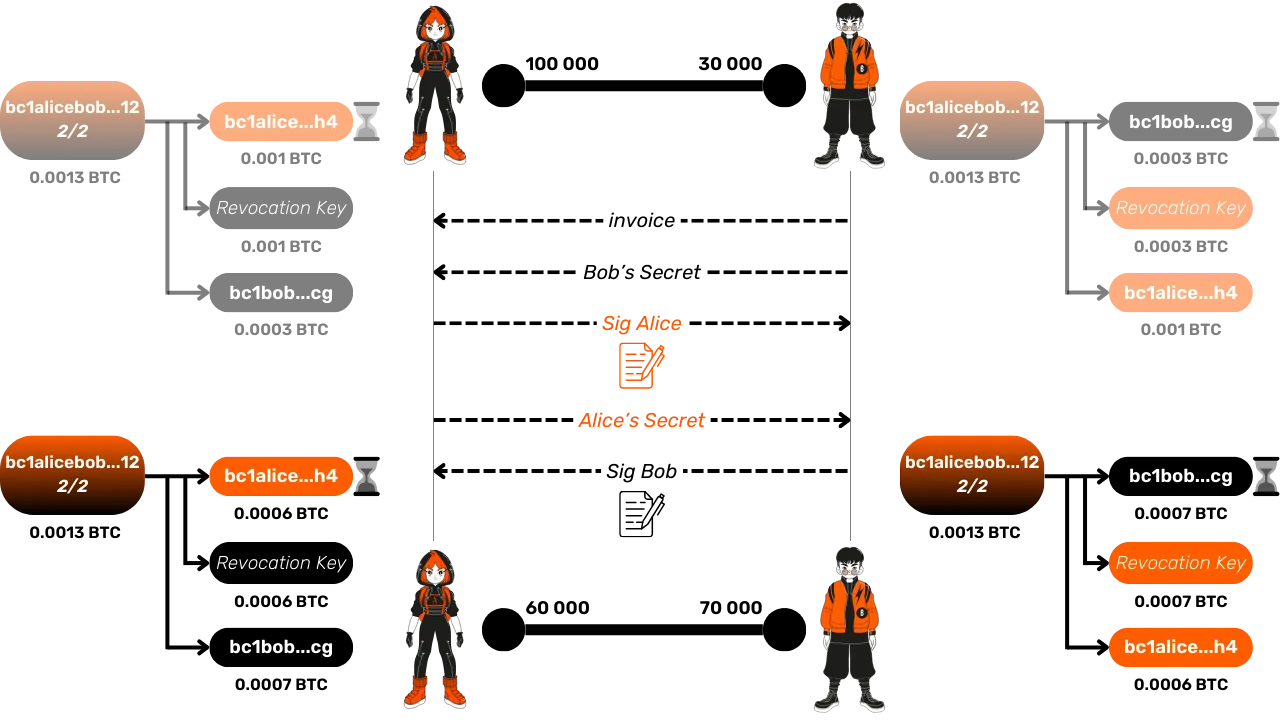

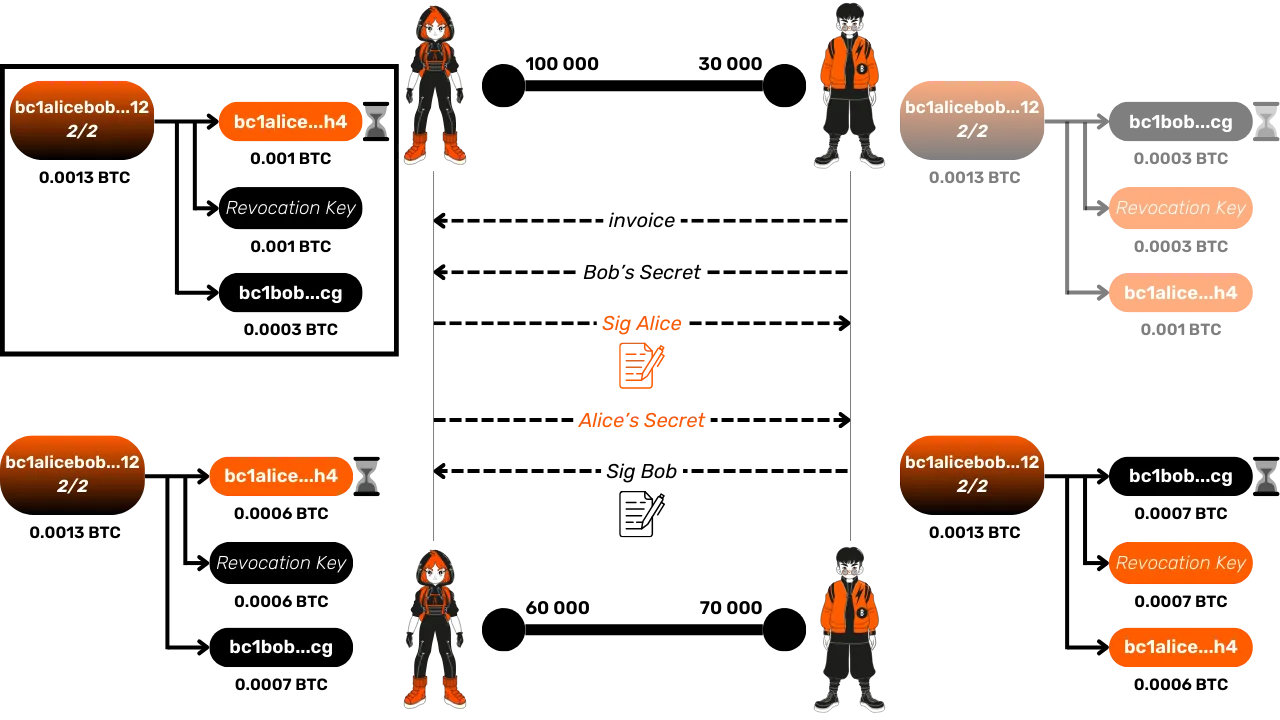

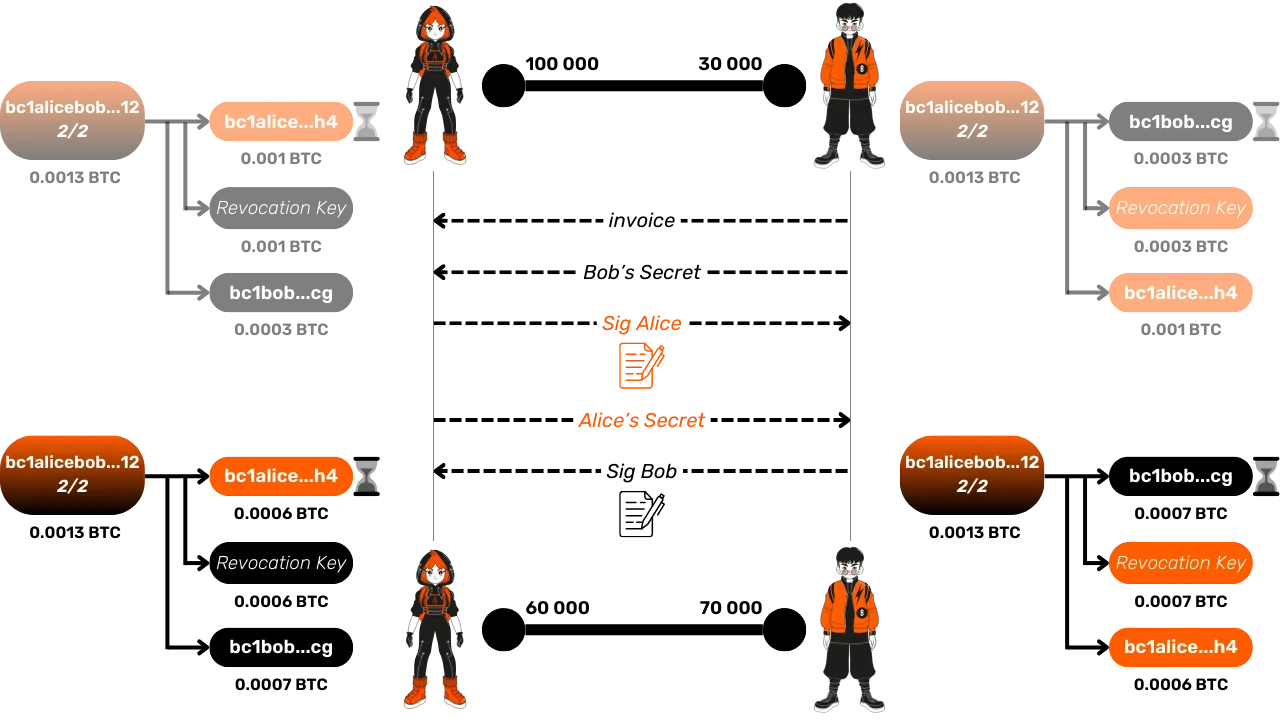

Transaction Update Process

When Alice and Bob update the state of the channel with a new Lightning transaction, they exchange in advance their respective secrets for the previous commitment transaction (the one that will become obsolete and could allow one of them to cheat). This means that, in the new state of the channel:

- Alice and Bob have a new commitment transaction representing the current distribution of funds after the Lightning transaction.

- Each has the other's secret for the previous transaction, which allows them to use the revocation key only if one of them tries to cheat by publishing a transaction with an old state in the Bitcoin nodes' mempools. Indeed, to punish the other party, it is necessary to hold both secrets and the other's commitment transaction, which includes the signed input. Without this transaction, the revocation key alone is useless. The only way to obtain this transaction is to retrieve it from the mempools (in the transactions waiting for confirmation) or in the confirmed transactions on the blockchain during the timelock, which proves that the other party is trying to cheat, whether intentionally or not.

Let's take an example to understand this process well:

- Initial State: Alice has 100,000 satoshis, Bob 30,000 satoshis.

- Bob wants to receive 40,000 satoshis from Alice via their Lightning

channel. To do this:

- He sends her an invoice along with his secret for the revocation key of his previous commitment transaction.

- In response, Alice provides her signature for Bob's new commitment transaction, as well as her secret for the revocation key of her previous transaction.

- Finally, Bob sends his signature for Alice's new commitment transaction.

- These exchanges allow Alice to send 40,000 satoshis to Bob on Lightning via their channel, and the new commitment transactions now reflect this new distribution of funds.

- If Alice attempts to publish the old commitment transaction where she still owned 100,000 satoshis, Bob, having obtained the revocation key, can immediately recover the funds using this key, while Alice is blocked by the timelock.

Even if, in this case, Bob has no economic interest in trying to cheat, if he does so anyway, Alice also benefits from symmetric protection offering her the same guarantees.

What should you take away from this chapter?

The commitment transactions on the Lightning Network include security mechanisms that reduce both the risk of cheating and the incentives to do so. Before signing a new commitment transaction, Alice and Bob exchange their respective secrets for the previous commitment transactions. If Alice tries to publish an old commitment transaction, Bob can use the revocation key to recover all the funds before Alice can (because she is blocked by the timelock), which punishes her for attempting to cheat.

This security system ensures that participants adhere to the rules of the Lightning Network, and they cannot profit from publishing old commitment transactions.

At this point in the training, you now know how Lightning channels are opened and how transactions within these channels work. In the next chapter, we will discover the different ways to close a channel and recover your bitcoins on the main blockchain.

Channel Closure

In this chapter, we will discuss closing a channel on the Lightning Network, which is done through a Bitcoin transaction, just like opening a channel. After seeing how transactions within a channel work, it is now time to see how to close a channel and recover the funds on the Bitcoin blockchain.

Reminder of the channel lifecycle

The lifecycle of a channel begins with its opening, via a Bitcoin transaction, then Lightning transactions are made within it, and finally, when the parties wish to recover their funds, the channel is closed through a second Bitcoin transaction. The intermediate transactions made on Lightning are represented by unpublished commitment transactions.

The three types of channel closure

There are three main ways to close this channel, which can be called the good, the brute, and the truant (inspired by Andreas Antonopoulos in Mastering the Lightning Network):

- The Good: the cooperative closure, where Alice and Bob agree to close the channel.

- The Bad: the forced closure, where one of the parties decides to close the channel honestly, but without the other's agreement.

- The Ugly: the closure with cheating, where one of the parties attempts to steal funds by publishing an old commitment transaction (any but not the last one, which reflects the actual and fair distribution of funds).

Let's take an example:

- Alice owns 100,000 satoshis and Bob 30,000 satoshis.

- This distribution is reflected in 2 commitment transactions (one per user) that are not published, but could be in the event of channel closure.

The Good: the cooperative closure

In a cooperative closure, Alice and Bob agree to close the channel. Here's how it goes:

- Alice sends a message to Bob via the Lightning communication protocol to propose closing the channel.

- Bob agrees, and the two parties make no further transactions in the channel.

- Alice and Bob negotiate together the fees of the closing transaction. These fees are generally calculated based on the Bitcoin fee market at the time of closure. It is important to note that it is always the person who opened the channel (Alice in our example) who pays the closing fees.

- They construct a new closing transaction. This transaction resembles a commitment transaction, but without timelocks or revocation mechanisms, since both parties are cooperating and there is no risk of cheating. This cooperative closing transaction is therefore different from commitment transactions.

For example, if Alice owns 100,000 satoshis and Bob 30,000 satoshis, the closing transaction will send 100,000 satoshis to Alice's address and 30,000 satoshis to Bob's address, without timelock constraints. Once this transaction is signed by both parties, it is published by Alice. Once the transaction is confirmed on the Bitcoin blockchain, the Lightning channel will be officially closed.

The cooperative closure is the preferred method of closing because it is fast (no timelock) and the transaction fees are adjusted according to the current Bitcoin market conditions. This avoids paying too little, which could risk blocking the transaction in the mempools, or overpaying unnecessarily, which leads to unnecessary financial loss for the participants.

The Bad: the forced closure

When Alice's node sends a message to Bob's asking for a cooperative closure, if he does not respond (for example, due to an internet outage or a technical problem), Alice can proceed with a forced closure by publishing the last signed commitment transaction. In this case, Alice will simply publish the last commitment transaction, which reflects the state of the channel at the time the last Lightning transaction took place with the correct distribution of funds.

This transaction includes a timelock for Alice's funds, making the closure slower.

Also, the fees of the commitment transaction may be unsuitable at the time of closure, as they were set when the transaction was created, sometimes several months before. Generally, Lightning clients overestimate fees to avoid future problems, but this can lead to excessive fees, or conversely too low.

In summary, forced closure is a last resort option when the peer no longer responds. It is slower and less economical than a cooperative closure. Therefore, it should be avoided as much as possible.

The cheat: cheating

Finally, a closure with cheating occurs when one of the parties tries to publish an old commitment transaction, often where they held more funds than they should. For example, Alice might publish an old transaction where she owned 120,000 satoshis, while she actually owns only 100,000 now.

Bob, to prevent this cheating, monitors the Bitcoin blockchain and its mempool to ensure Alice does not publish an old transaction. If Bob detects a cheating attempt, he can use the revocation key to recover Alice's funds and punish her by taking the entire funds of the channel. Since Alice is blocked by the timelock on her output, Bob has time to spend it without a timelock on his side to recover the whole sum on an address he owns.

Obviously, cheating can potentially succeed if Bob does not act within the time imposed by the timelock on Alice's output. In this case, Alice's output is unlocked, allowing her to consume it to create a new output to an address she controls.

What should you take away from this chapter?

There are three ways to close a channel:

- Cooperative Closure: Fast and less expensive, where both parties agree to close the channel and publish a tailored closing transaction.

- Forced Closure: Less desirable, as it relies on publishing a commitment transaction, with potentially unsuitable fees and a timelock, which slows down the closure.

- Cheating: If one of the parties tries to steal funds by publishing an old transaction, the other can use the revocation key to punish this cheating.

In the upcoming chapters, we will explore the Lightning Network from a broader perspective, focusing on how its network operates.

A Liquidity Network

Lightning Network

In this chapter, we will explore how payments on the Lightning Network can reach a recipient even if they are not directly connected by a payment channel. Lightning is, indeed, a network of payment channels, which allows funds to be sent to a distant node through the channels of other participants. We will discover how payments are routed across the network, how liquidity moves between channels, and how transaction fees are calculated.

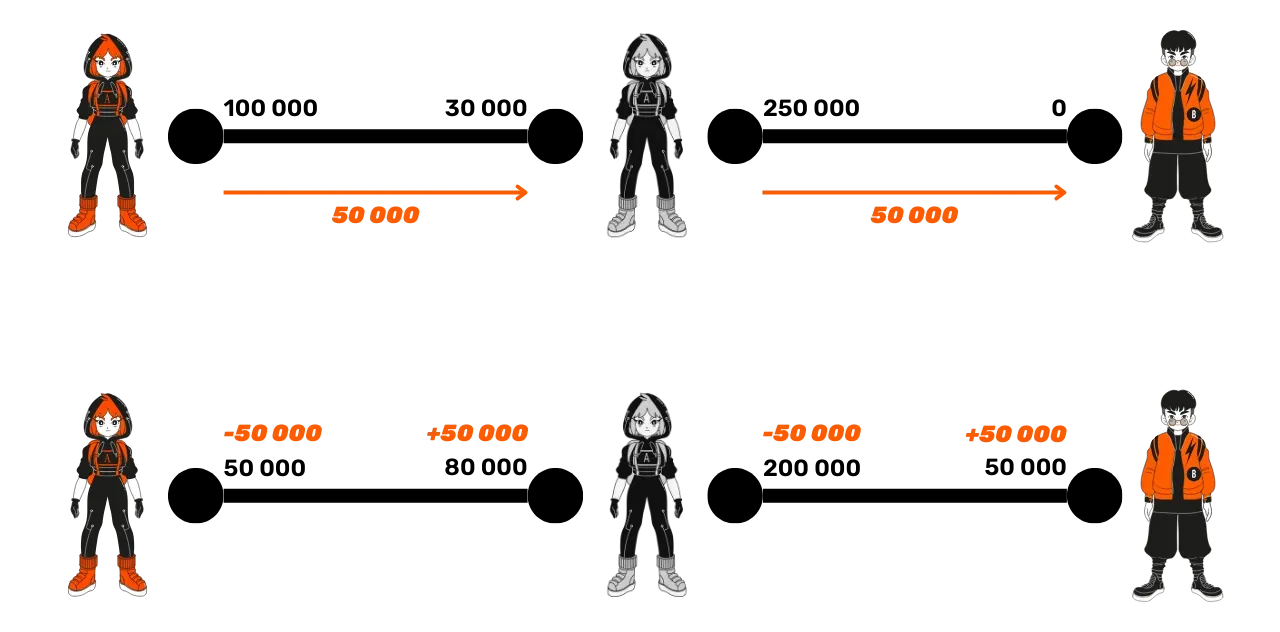

The Network of Payment Channels

On the Lightning Network, a transaction corresponds to a transfer of funds between two nodes. As seen in previous chapters, it is necessary to open a channel with someone to perform Lightning transactions. This channel allows for an almost infinite number of off-chain transactions before closing it to reclaim the on-chain balance. However, this method has the disadvantage of requiring a direct channel with the other person to receive or send funds, which implies an opening transaction and a closing transaction for each channel. If I plan to make a large number of payments with this person, opening and closing a channel becomes cost-effective. Conversely, if I only need to perform a few Lightning transactions, opening a direct channel is not advantageous, as it would cost me 2 on-chain transactions for a limited number of off-chain transactions. This case might occur, for example, when wanting to pay with Lightning at a merchant without planning to return.

To solve this problem, the Lightning Network allows for routing a payment through several channels and intermediary nodes, thus enabling a transaction without a direct channel with the other person.

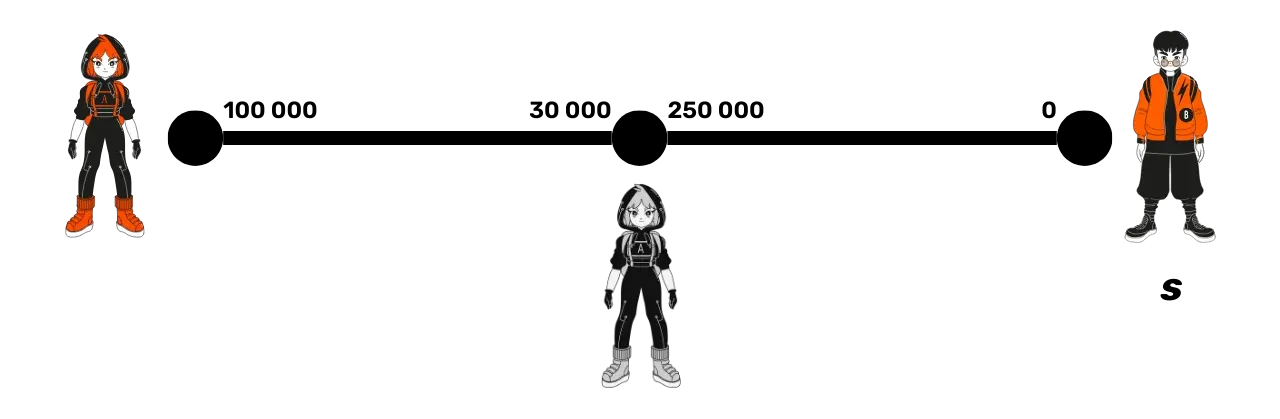

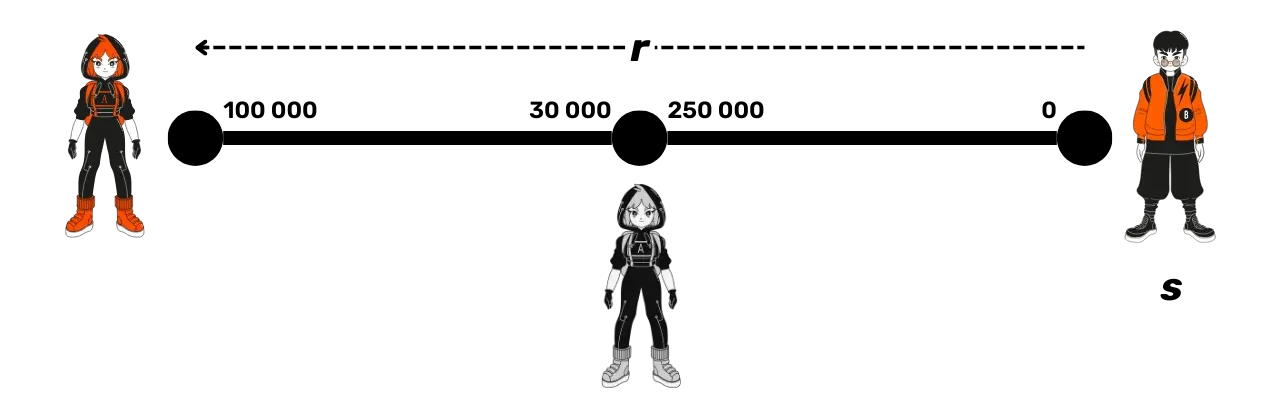

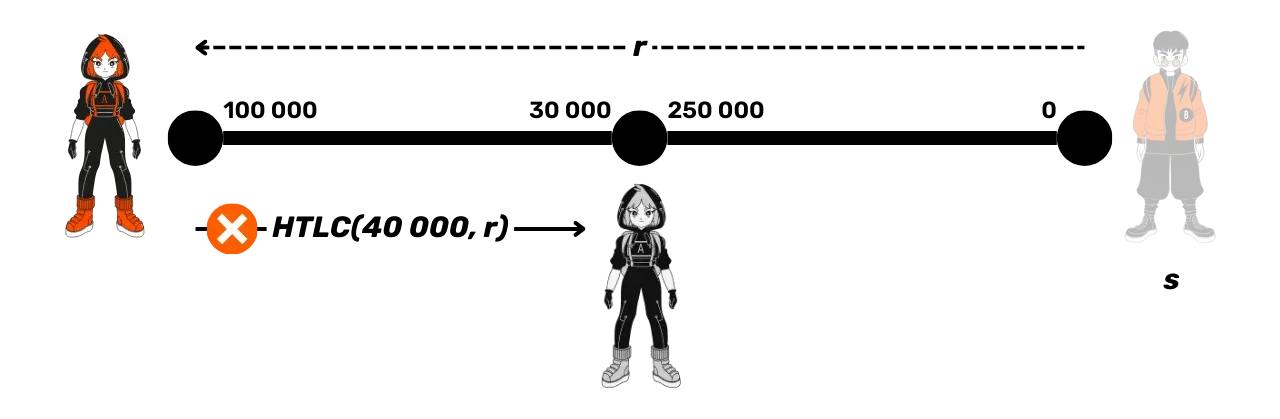

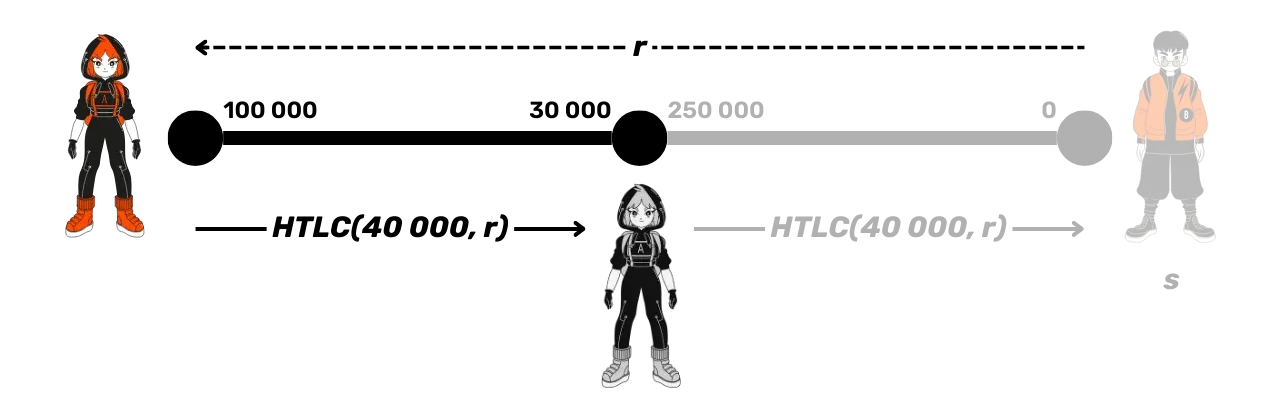

For example, imagine that:

- Alice (in orange) has a channel with Suzie (in gray) with 100,000 satoshis on her side and 30,000 satoshis on Suzie's side.

- Suzie has a channel with Bob in which she owns 250,000 satoshis and where Bob has no satoshis.

If Alice wants to send funds to Bob without opening a direct channel with him, she will have to go through Suzie, and each channel will need to adjust the liquidity on each side. The sent satoshis remain within their respective channels; they don't actually "cross" the channels, but the transfer is made via an adjustment of the internal liquidity in each channel.

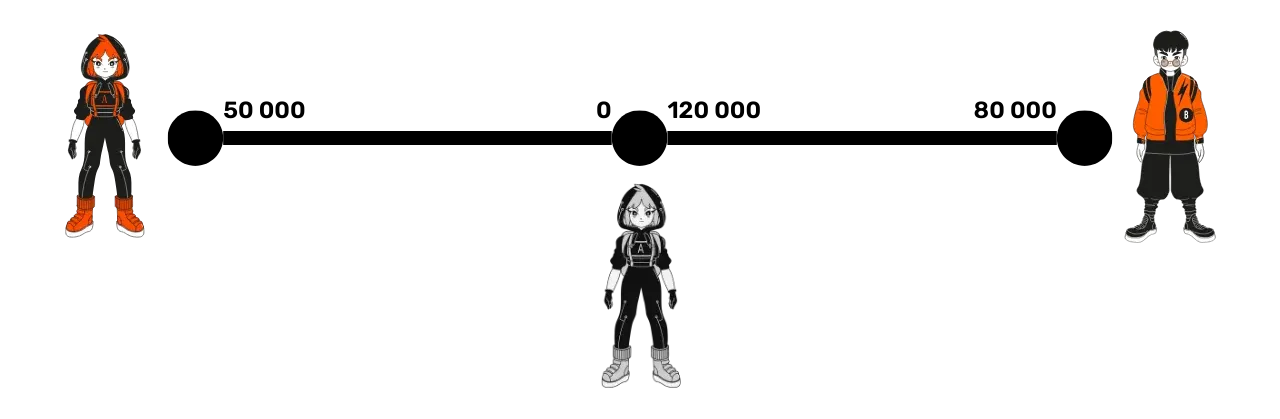

Suppose Alice wants to send 50,000 satoshis to Bob:

- Alice sends 50,000 satoshis to Suzie in their common channel.

- Suzie replicates this transfer by sending 50,000 satoshis to Bob in their channel.

Thus, the payment is routed to Bob via a movement of liquidity in each channel. At the end of the operation, Alice ends up with 50,000 sats. She has indeed transferred 50,000 sats since initially, she had 100,000. Bob, on his side, ends up with an additional 50,000 sats. For Suzie (the intermediate node), this operation is neutral: initially, she had 30,000 sats in her channel with Alice and 250,000 sats in her channel with Bob, a total of 280,000 sats. After the operation, she holds 80,000 sats in her channel with Alice and 200,000 sats in her channel with Bob, which is the same sum as at the start.

This transfer is thus limited by the available liquidity in the direction of the transfer.

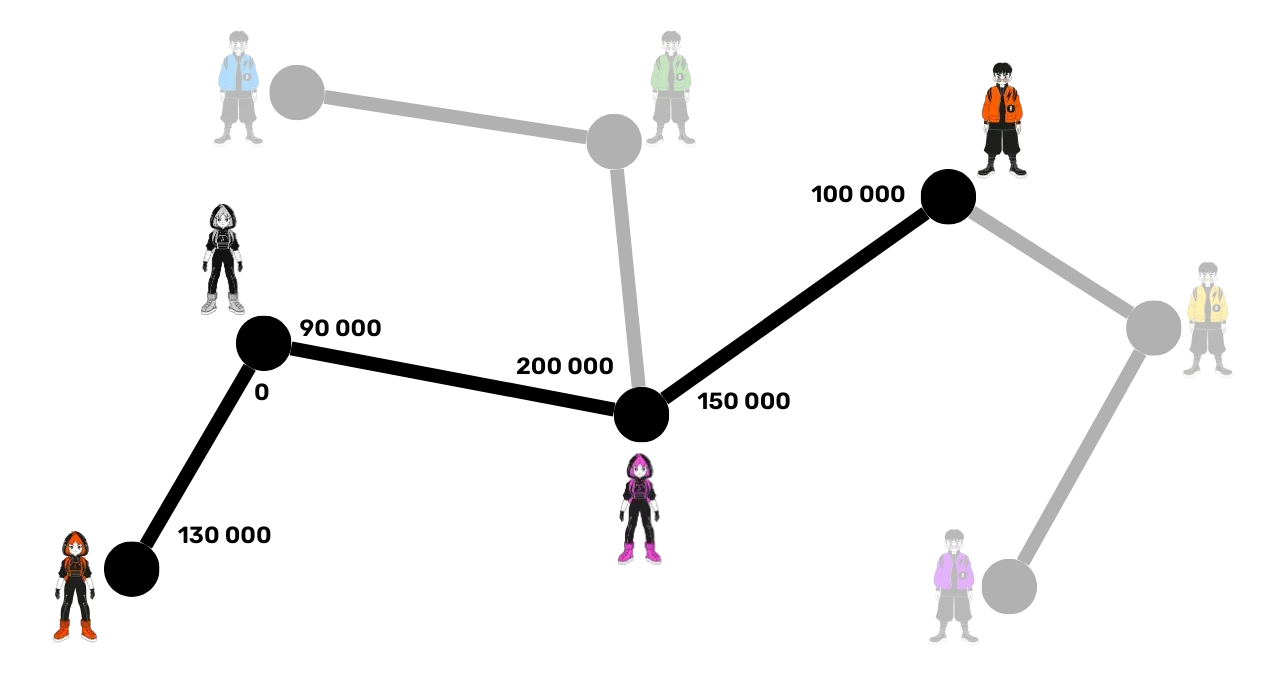

Calculation of the Route and Liquidity Limits

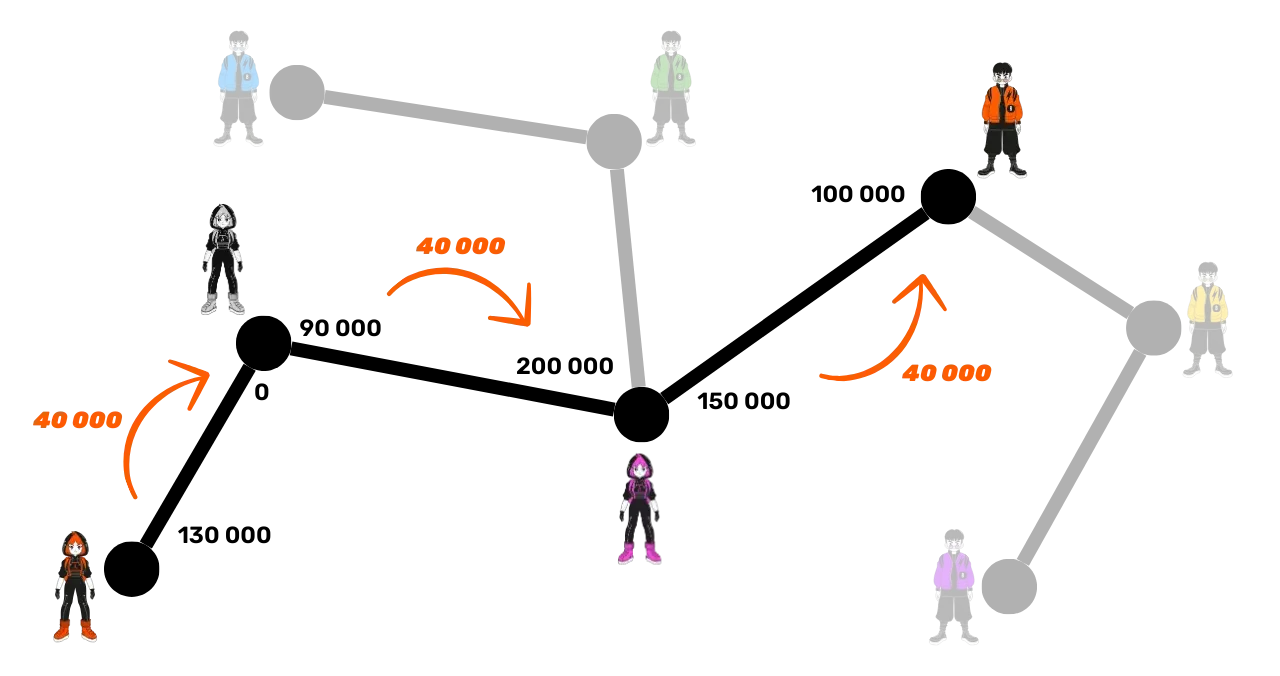

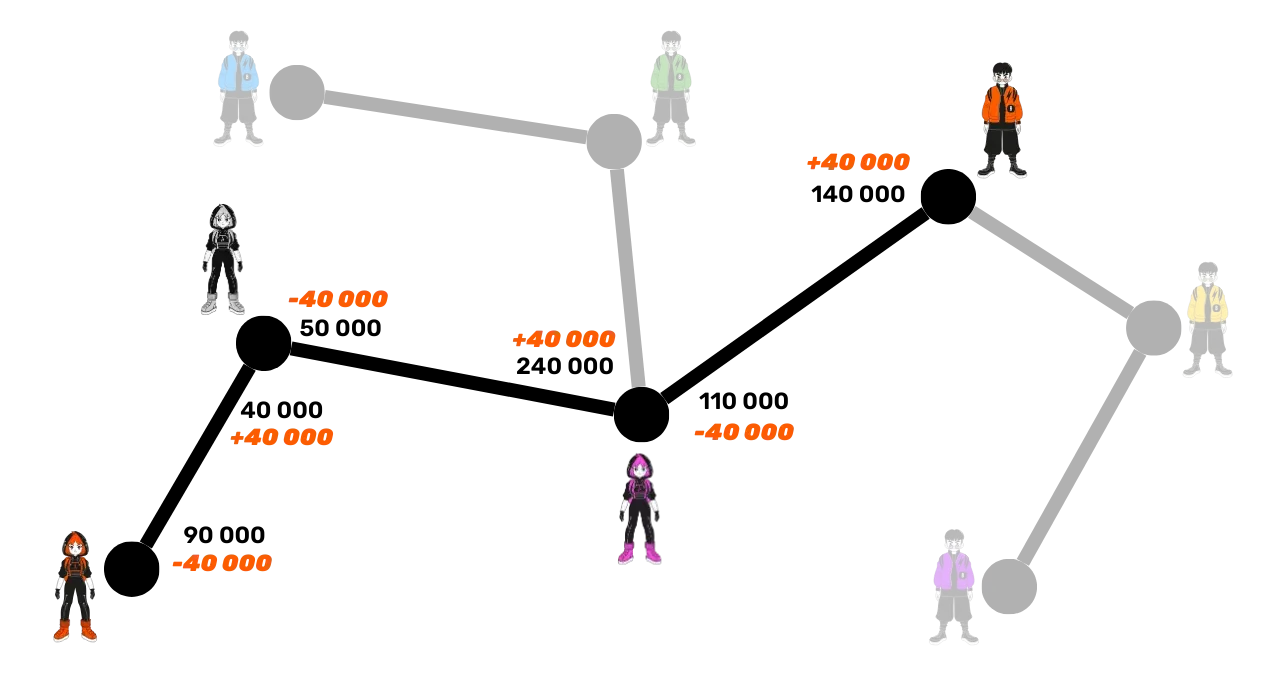

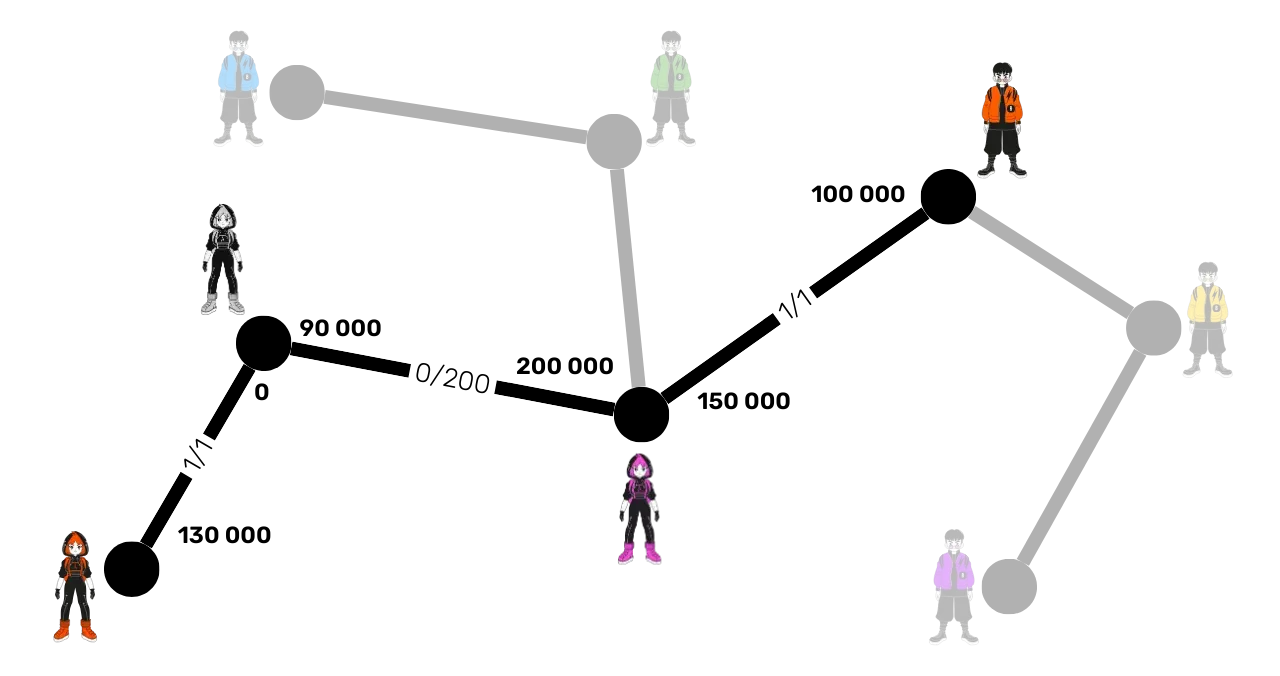

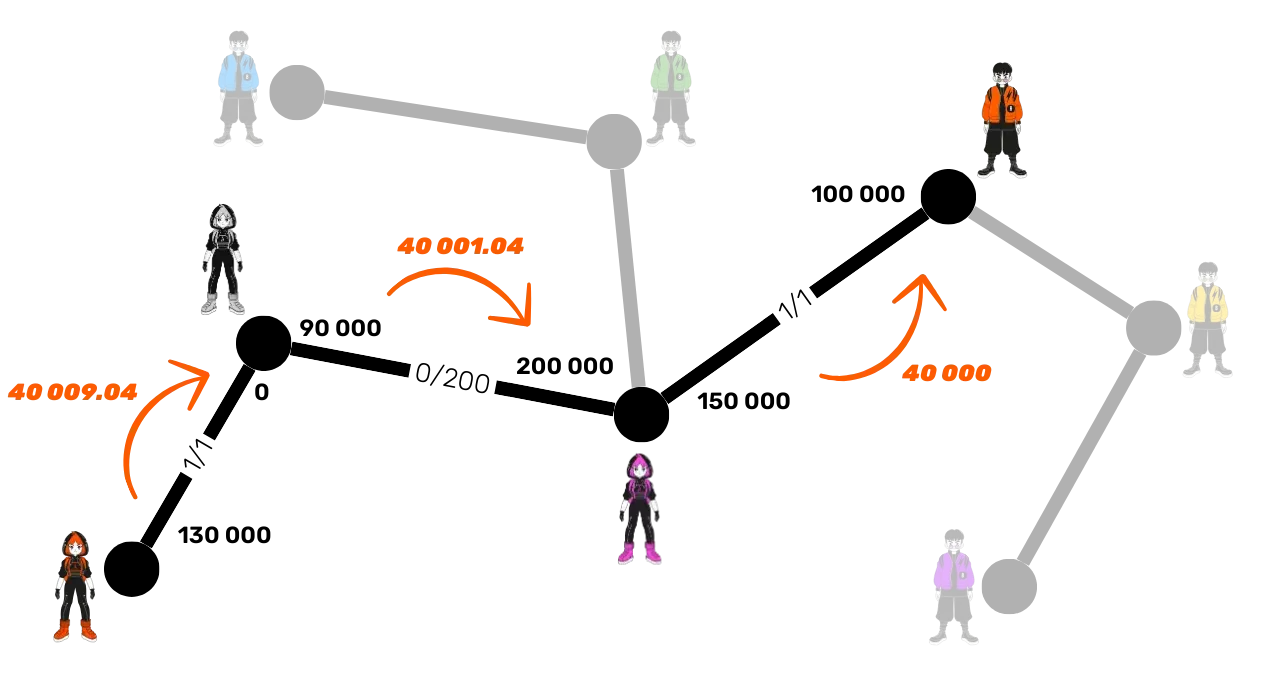

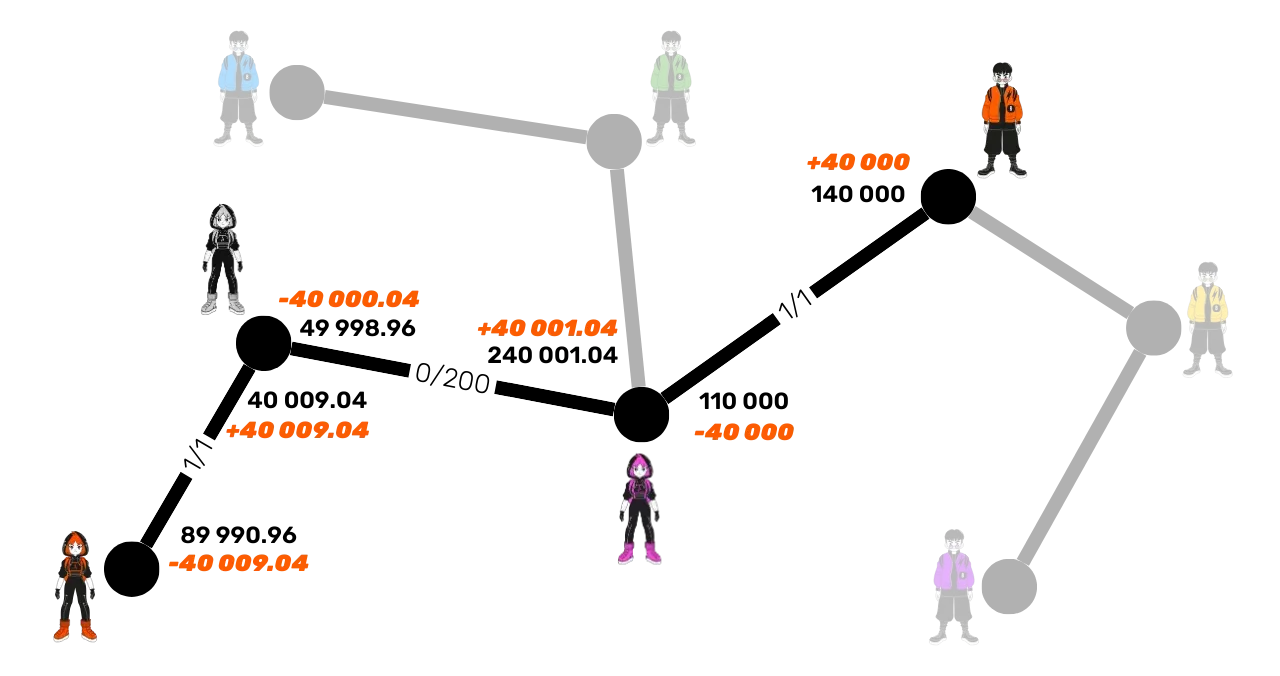

Let's take a theoretical example of another network with:

- 130,000 satoshis on Alice's side (in orange) in her channel with Suzie (in gray).

- 90,000 satoshis on Suzie's side and 200,000 satoshis on Carol's side (in pink).

- 150,000 satoshis on Carol's side and 100,000 satoshis on Bob's side.

The maximum Alice can send to Bob in this configuration is 90,000 satoshis, as she is limited by the smallest liquidity available in the channel from Suzie to Carol. In the opposite direction (from Bob to Alice), no payment is possible because Suzie's side in the channel with Alice contains no satoshis. Therefore, there is no route usable for a transfer in this direction. Alice sends 40,000 satoshis to Bob through the channels:

- Alice transfers 40,000 satoshis to her channel with Suzie.

- Suzie transfers 40,000 satoshis to Carol in their shared channel.

- Carol finally transfers 40,000 satoshis to Bob.

The satoshis sent in each channel remain in the channel, so the satoshis sent by Carol to Bob are not the same as those sent by Alice to Suzie. The transfer is made only by adjusting the liquidity inside each channel. Moreover, the total capacity of the channels remains unchanged.

As in the previous example, after the transaction, the source node (Alice) has 40,000 satoshis less. The intermediate nodes (Suzie and Carol) retain the same total amount, making the operation neutral for them. Finally, the destination node (Bob) receives an additional 40,000 satoshis.

The role of the intermediate nodes is therefore very important in the functioning of the Lightning Network. They facilitate transfers by offering multiple paths for payments. To encourage these nodes to provide their liquidity and participate in routing payments, routing fees are paid to them.

Routing Fees

The intermediate nodes apply fees to allow payments to pass through their channels. These fees are set by each node for each channel. The fees consist of 2 elements:

- "Base fee": a fixed amount per channel, often 1 sat by default, but customizable.

- "Variable fee": a percentage of the transferred amount, calculated in parts per million (ppm). By default, it is 1 ppm (1 sat per million satoshis transferred), but it can also be adjusted.

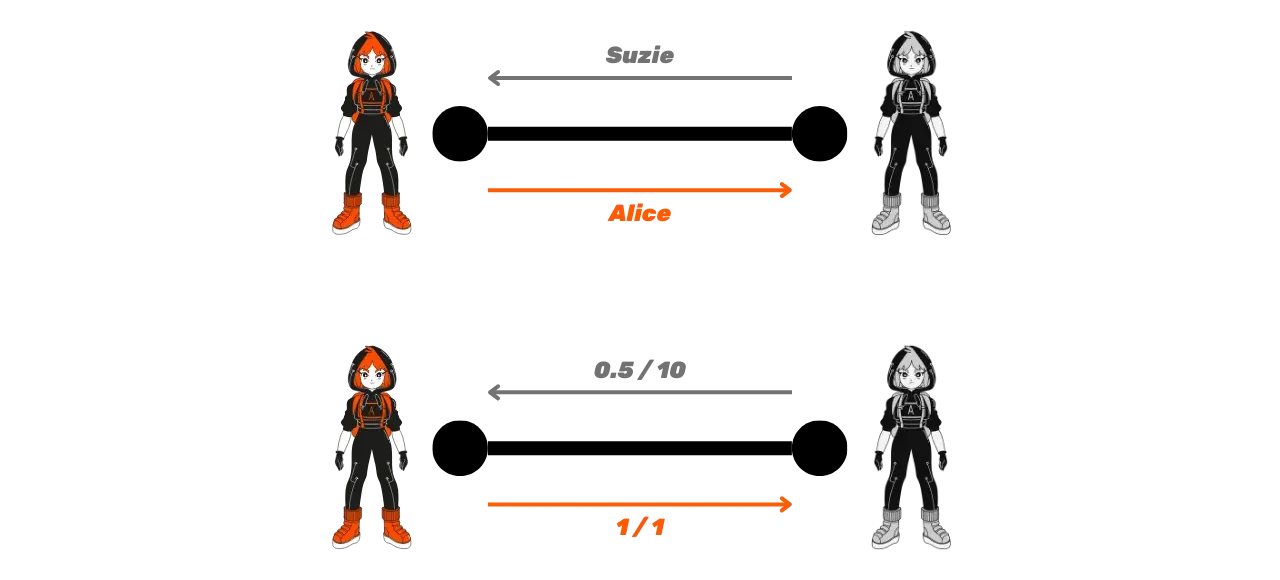

The fees also differ depending on the direction of the transfer. For example, for a transfer from Alice to Suzie, Alice's fees apply. Conversely, from Suzie to Alice, Suzie's fees are used.

For example, for a channel between Alice and Suzie, we could have:

- Alice: base fee of 1 sat and 1 ppm for variable fees.

- Suzie: base fee of 0.5 sat and 10 ppm for variable fees.

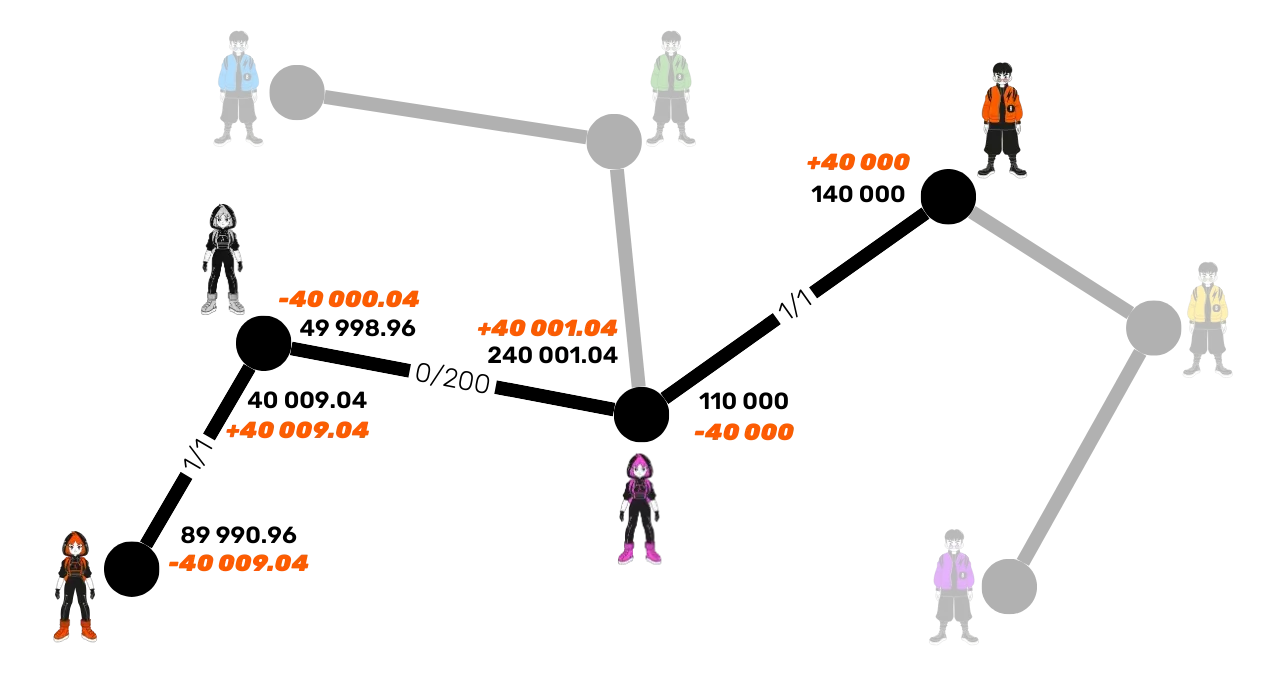

To better understand how fees work, let's study the same Lightning Network as before, but now with the following routing fees:

- Channel Alice - Suzie: base fee of 1 satoshi and 1 ppm for Alice.

- Channel Suzie - Carol: base fee of 0 satoshi and 200 ppm for Suzie.

- Carol - Bob Channel: base fee of 1 satoshi and 1 ppm for

Suzie 2.

For the same payment of 40,000 satoshis to Bob, Alice will have to send a little more, as each intermediary node will deduct its fees:

Carol deducts 1.04 satoshis on the channel with Bob:

f*{\text{Carol-Bob}} = \text{base fee} + \left(\frac{\text{ppm} \times \text{amount}}{10^6}\right)f*{\text{Carol-Bob}} = 1 + \frac{1 \times 40000}{10^6} = 1 + 0.04 = 1.04 \text{ sats}Suzie deducts 8 satoshis in fees on the channel with Carol:

f*{\text{Suzie-Carol}} = \text{base fee} + \left(\frac{\text{ppm} \times \text{amount}}{10^6}\right)f*{\text{Suzie-Carol}} = 0 + \frac{200 \times 40001.04}{10^6} = 0 + 8.0002 \approx 8 \text{ sats}

The total fees for this payment on this path are therefore 9.04 satoshis. Thus, Alice must send 40,009.04 satoshis for Bob to receive exactly 40,000 satoshis.

The liquidity is therefore updated:

Onion Routing

To route a payment from the sender to the recipient, the Lightning Network uses a method called "onion routing". Unlike the routing of classical data, where each router decides the direction of the data based on their destination, onion routing works differently:

The sending node calculates the entire route: Alice, for example, determines that her payment must go through Suzie and Carol before reaching Bob.

Each intermediary node knows only its immediate neighbor: Suzie only knows that she received funds from Alice and that she must transfer them to Carol. However, Suzie does not know if Alice is the source node or an intermediary node, and she also does not know if Carol is the recipient node or just another intermediary node. This principle also applies to Carol and all other nodes on the path. Onion routing thus preserves the confidentiality of transactions by masking the identity of the sender and the final recipient. To ensure the transmitting node can calculate a complete route to the recipient in onion routing, it must maintain a network graph to know its topology and determine possible routes. What should you take away from this chapter?

On Lightning, payments can be routed between nodes indirectly connected through intermediary channels. Each of these intermediary nodes facilitates the liquidity relay.

Intermediary nodes receive a commission for their service, consisting of fixed and variable fees.

Onion routing allows the transmitting node to calculate the complete route without intermediary nodes knowing the source or final destination.

In this chapter, we explored payment routing on the Lightning Network. But a question arises: what prevents intermediary nodes from accepting an incoming payment without forwarding it to the next destination, with the aim of intercepting the transaction? This is precisely the role of HTLCs that we will study in the following chapter.

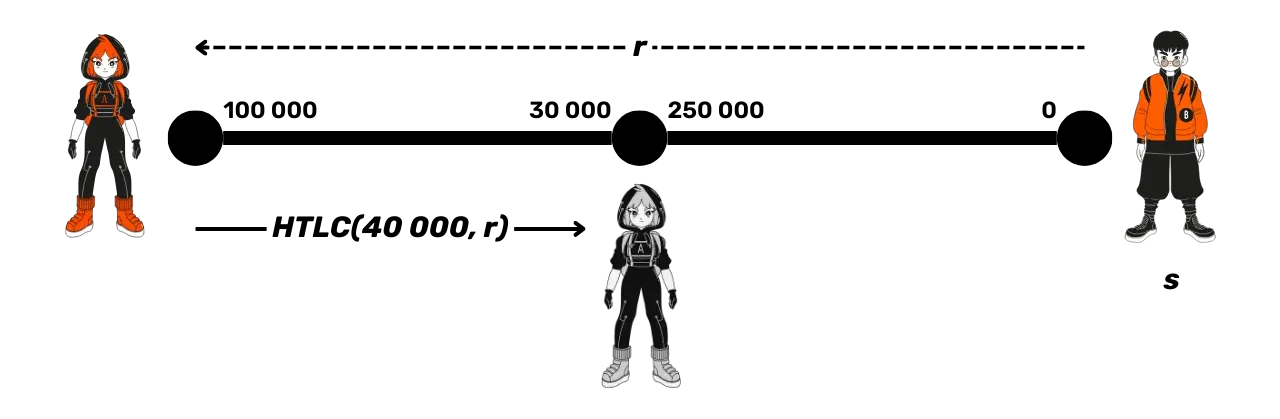

HTLC – Hashed Time Locked Contract

In this chapter, we will discover how Lightning allows payments to transit through intermediary nodes without needing to trust them, thanks to HTLC (Hashed Time-Locked Contracts). These smart contracts ensure that each intermediary node will only receive the funds from its channel if it forwards the payment to the final recipient, otherwise, the payment will not be validated.

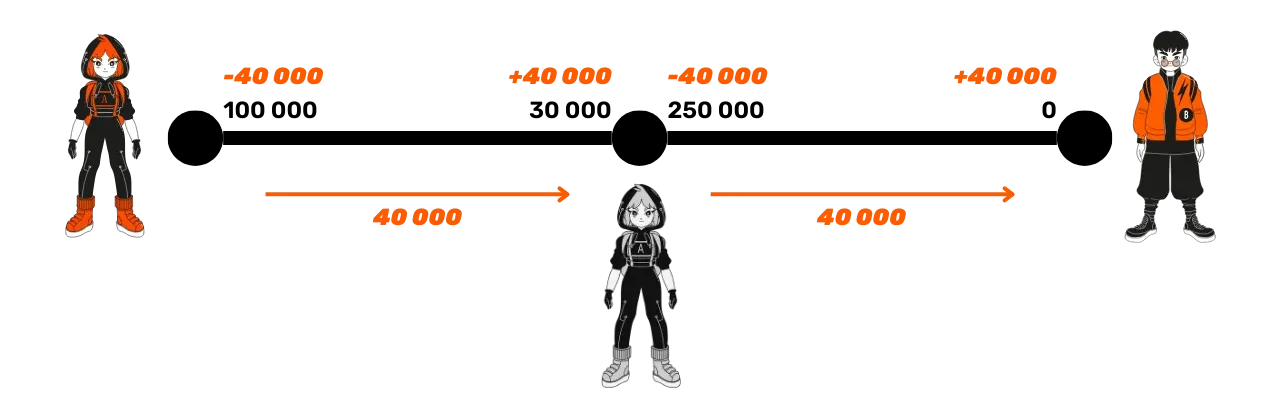

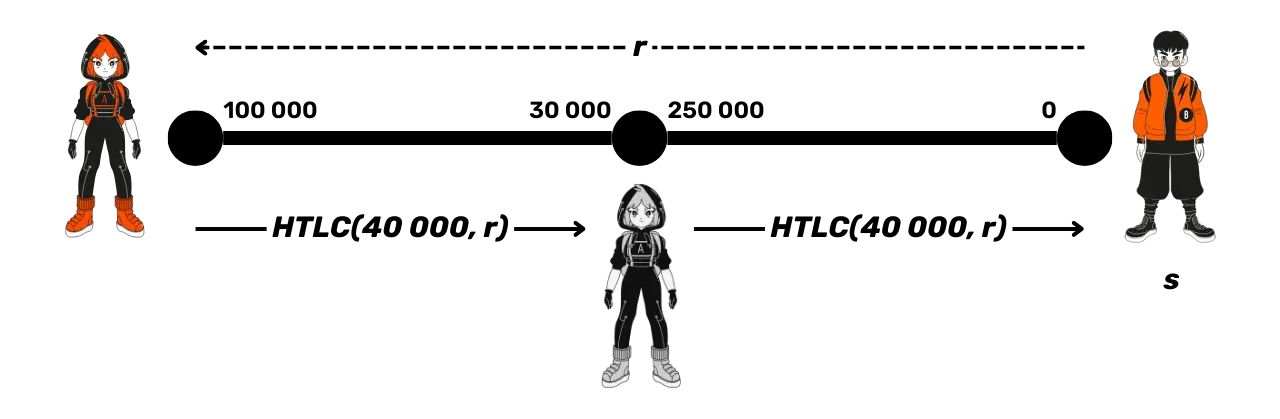

The issue that arises for payment routing is therefore the necessary trust in intermediary nodes, and among the intermediary nodes themselves. To illustrate this, let's revisit our simplified Lightning network example with 3 nodes and 2 channels:

- Alice has a channel with Suzie.

- Suzie has a channel with Bob.

Alice wants to send 40,000 sats to Bob but she does not have a direct channel with him and does not wish to open one. She looks for a route and decides to go through Suzie's node.

If Alice naively sends 40,000 satoshis to Suzie hoping that Suzie will transfer this sum to Bob, Suzie could keep the funds for herself and not transmit anything to Bob.

To avoid this situation, on Lightning, we use HTLCs (Hashed Time-Locked Contracts),

which make the payment to the intermediary node conditional, meaning Suzie must

meet certain conditions to access Alice's funds and transfer them to Bob.

To avoid this situation, on Lightning, we use HTLCs (Hashed Time-Locked Contracts),

which make the payment to the intermediary node conditional, meaning Suzie must

meet certain conditions to access Alice's funds and transfer them to Bob.

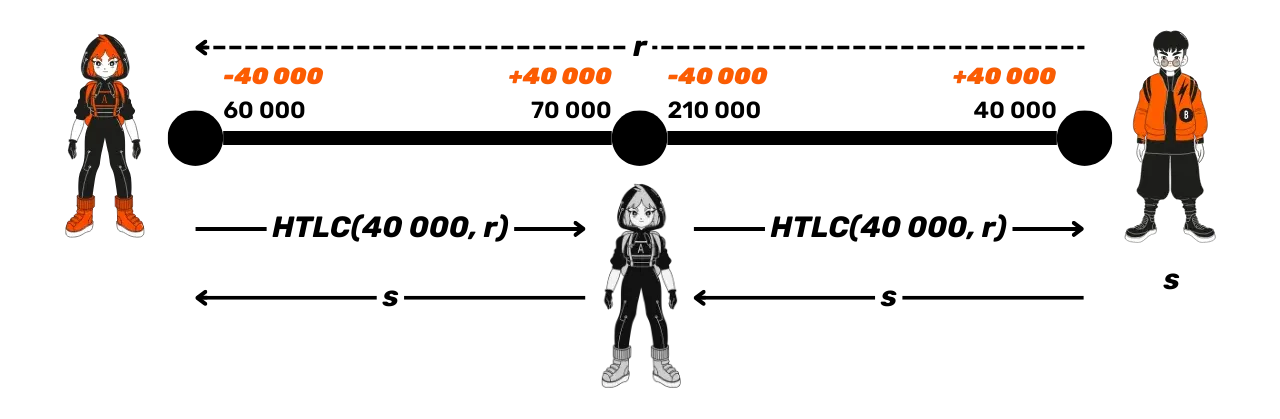

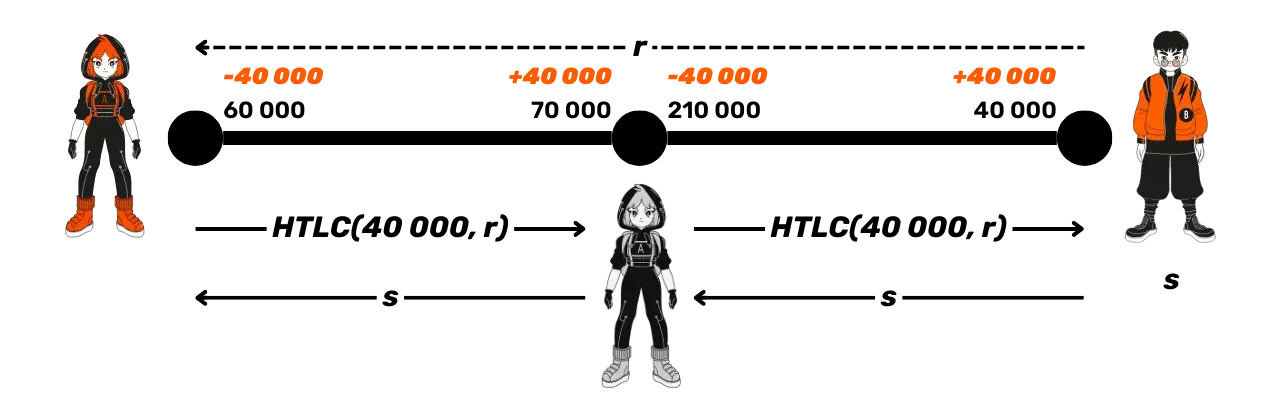

How HTLCs Work

An HTLC is a special contract based on two principles:

- Access condition: The recipient must reveal a secret to unlock the payment due to them.

- Expiration: If the payment is not fully completed within a defined period, it is canceled, and the funds return to the sender.

Here's how this process works in our example with Alice, Suzie, and Bob:

Creating the secret: Bob generates a random secret noted as s (the preimage), and calculates its hash noted as r with the hash function noted as h. We have:

r = h(s)Using a hash function makes it impossible to find s with only h(s), but if s is provided, it's easy to verify that it corresponds to h(s).

Sending the payment request: Bob sends an invoice to Alice asking for a payment. This invoice notably includes the hash r.

Sending the conditional payment: Alice sends an HTLC of 40,000 satoshis to Suzie. The condition for Suzie to receive these funds is that she provides Alice with a secret s' that satisfies the following equation:

h(s') = r

Transferring the HTLC to the final recipient: Suzie, to obtain the 40,000 satoshis from Alice, must transfer a similar HTLC of 40,000 satoshis to Bob, who has the same condition, namely that he must provide Suzie with a secret s' that satisfies the equation:

h(s') = r

Validation by the secret s: Bob provides s to Suzie to receive the 40,000 satoshis promised in the HTLC. With this secret, Suzie can then unlock Alice's HTLC and obtain the 40,000 satoshis from Alice. The payment is then correctly routed to Bob.

This process prevents Suzie from keeping Alice's funds without completing the

transfer to Bob, as she must send the payment to Bob to obtain the secret s and thus unlock Alice's HTLC. The operation remains the same even

if the route includes several intermediary nodes: it is simply a matter of repeating

Suzie's steps for each intermediary node. Each node is protected by the conditions

of the HTLCs, because unlocking the last HTLC by the recipient automatically

triggers the unlocking of all other HTLCs in a cascade.

This process prevents Suzie from keeping Alice's funds without completing the

transfer to Bob, as she must send the payment to Bob to obtain the secret s and thus unlock Alice's HTLC. The operation remains the same even

if the route includes several intermediary nodes: it is simply a matter of repeating

Suzie's steps for each intermediary node. Each node is protected by the conditions

of the HTLCs, because unlocking the last HTLC by the recipient automatically

triggers the unlocking of all other HTLCs in a cascade.

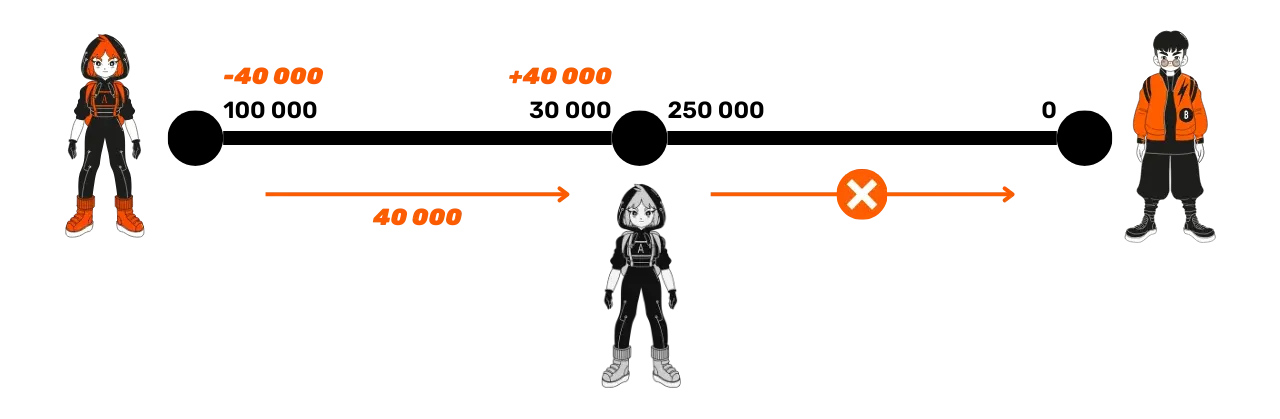

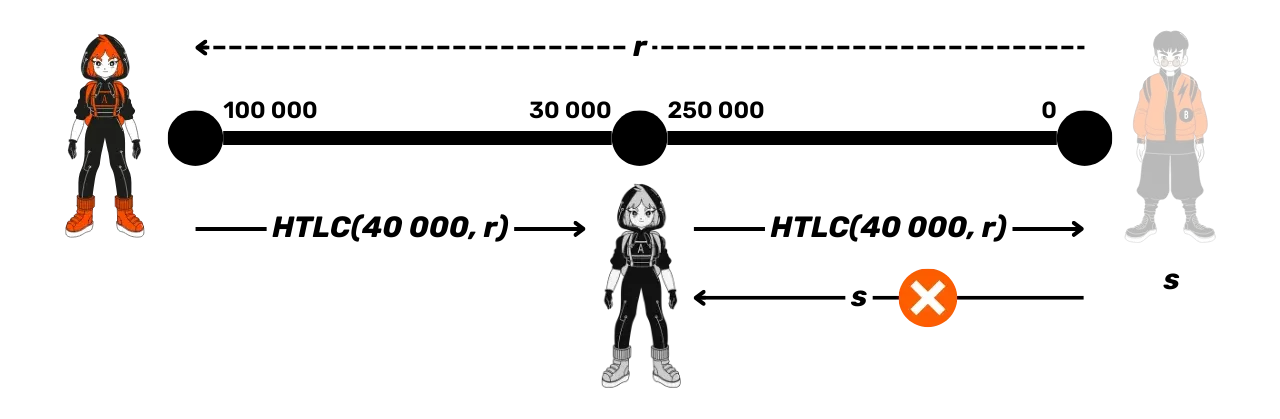

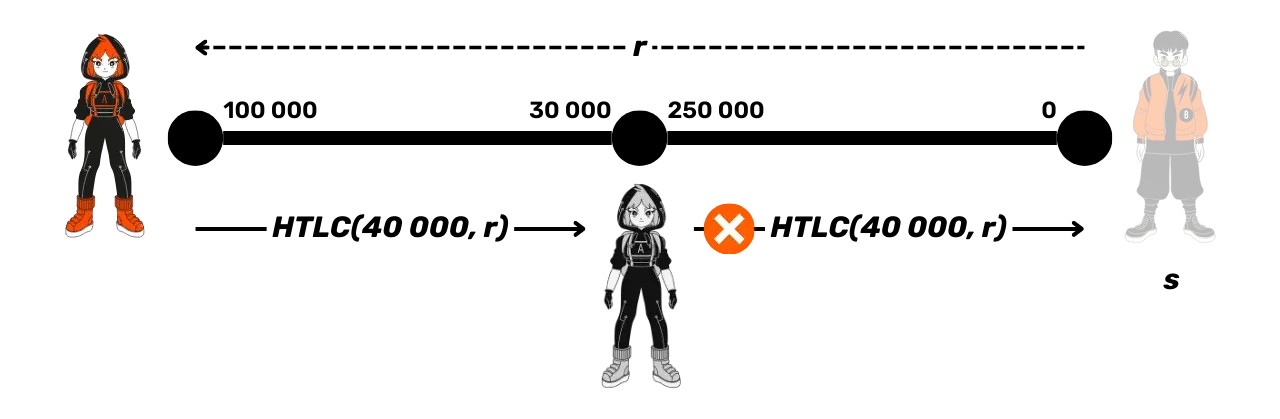

Expiration and management of HTLCs in case of problems

If during the payment process, one of the intermediary nodes, or the recipient node, stops responding, especially in case of an internet or power outage, then the payment cannot be completed, because the secret needed to unlock the HTLCs is not transmitted. Taking our example with Alice, Suzie, and Bob, this problem occurs, for example, if Bob does not transmit the secret s to Suzie. In this case, all the HTLCs upstream of the path are blocked, and the funds they secure as well.

To avoid this, HTLCs on Lightning have an expiration that allows for the removal of the HTLC if it is not completed after a certain time. The expiration follows a specific order since it starts first with the HTLC closest to the recipient, and then progressively moves up to the transaction's issuer. In our example, if Bob never gives the secret s to Suzie, this would first cause Suzie's HTLC towards Bob to expire.

Then the HTLC from Alice to Suzie.

If the order of expiration was reversed, Alice could recover her payment before Suzie could protect herself from potential cheating. Indeed, if Bob comes back to claim his HTLC while Alice has already removed hers, Suzie would be at a disadvantage. This cascading order of HTLC expiration thus ensures that no intermediary node suffers from unfair losses.

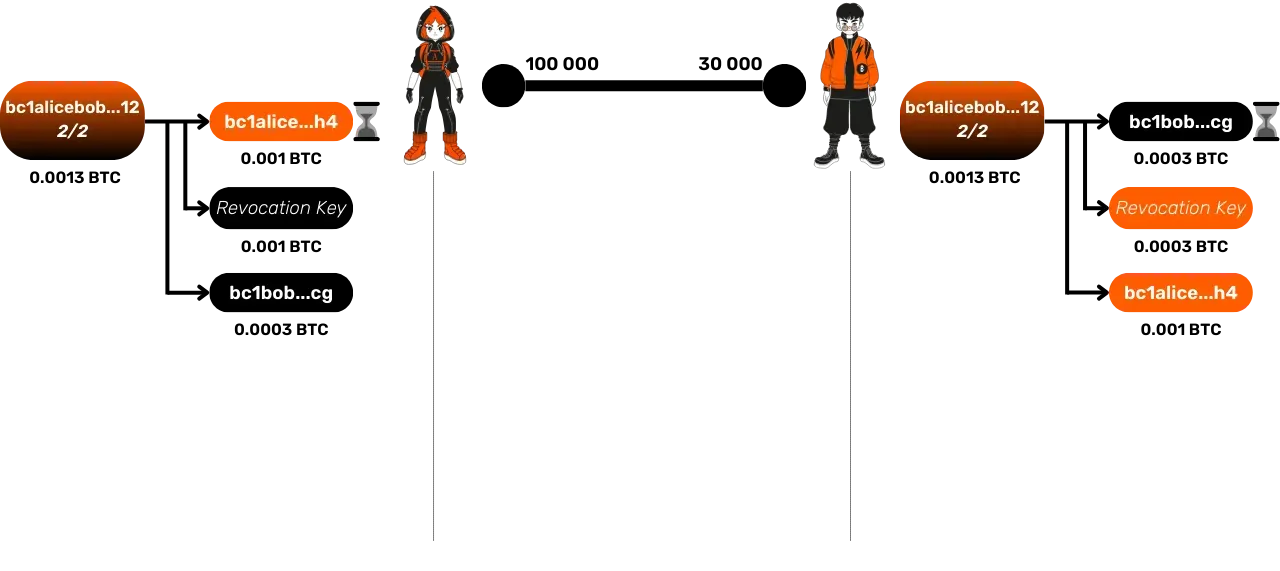

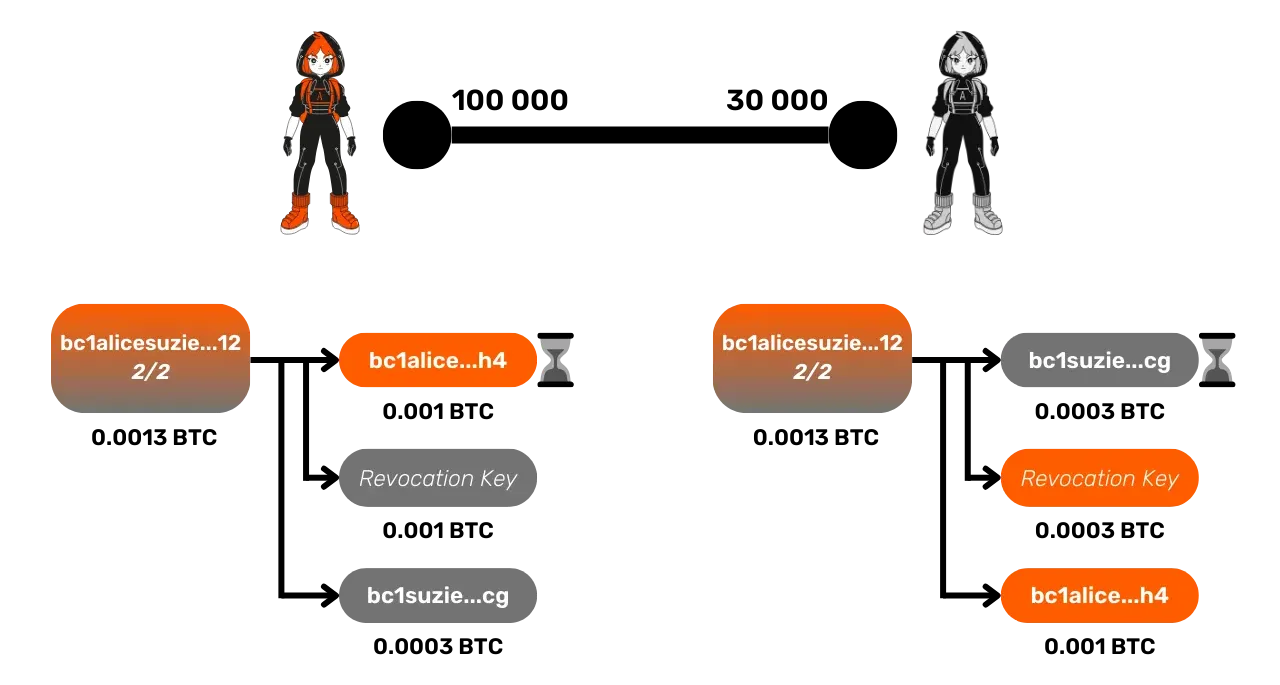

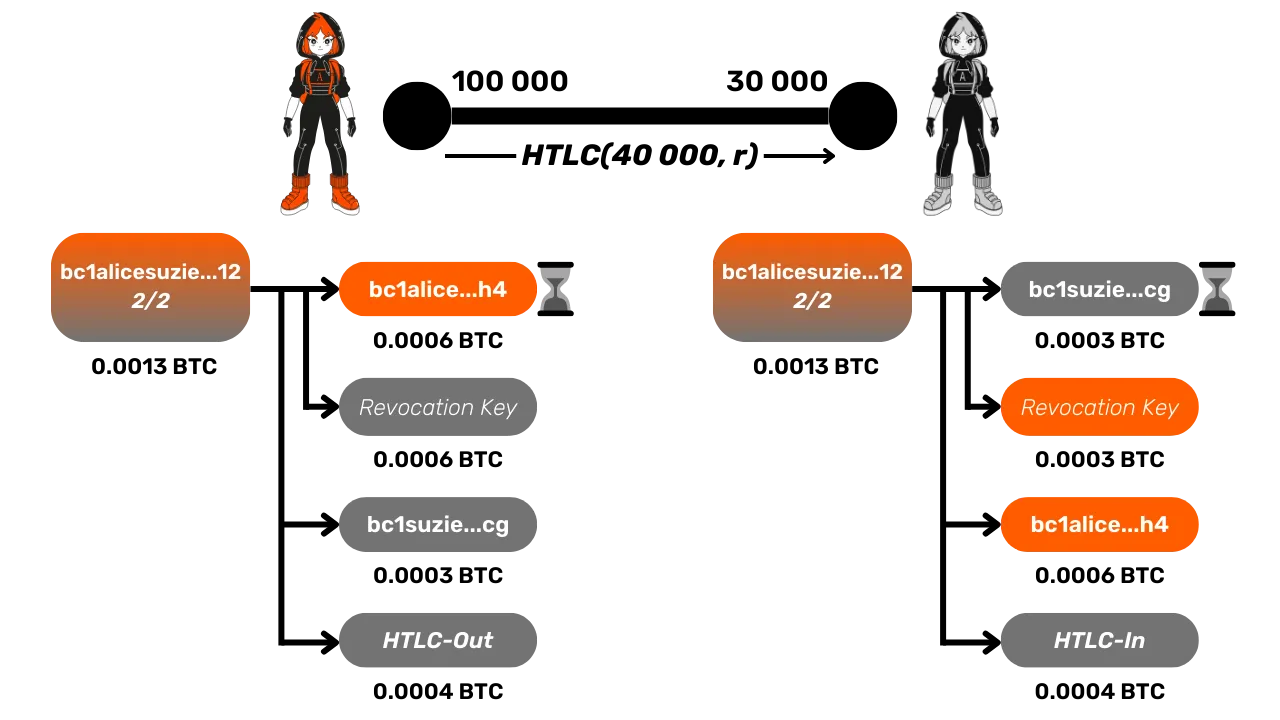

Representation of HTLCs in commitment transactions

Commitment transactions represent HTLCs in such a way that the conditions

they impose on Lightning can be transferred to Bitcoin in the event of a

forced channel closure during the lifespan of an HTLC. As a reminder,

commitment transactions represent the current state of the channel between

the two users and allow for a unilateral forced closure in case of issues.

With each new state of the channel, 2 commitment transactions are created:

one for each party. Let's revisit our example with Alice, Suzie, and Bob,

but look more closely at what happens at the channel level between Alice and

Suzie when the HTLC is created.

Before the start of the 40,000 sats payment between Alice and Bob, Alice has 100,000 sats in her channel with Suzie, while Suzie holds 30,000. Their commitment transactions are as follows:

Alice has just received Bob's invoice, which notably contains r, the hash of the secret. She can thus construct an HTLC of 40,000 satoshis with Suzie. This HTLC is represented in the latest commitment transactions as an output called "HTLC Out" on Alice's side, since the funds are outgoing, and "HTLC In" on Suzie's side, since the funds are incoming.

These outputs associated with the HTLC share exactly the same conditions, namely:

- If Suzie is able to provide the secret s, she can unlock this output immediately and transfer it to an address she controls.

- If Suzie does not possess the secret s, she cannot unlock this output, and Alice will be able to unlock it after a timelock to send it to an address she controls. The timelock thus grants Suzie a period to react if she obtains s.

These conditions apply only if the channel is closed (i.e., a commitment transaction is published on-chain) while the HTLC is still active on Lightning, meaning the payment between Alice and Bob has not yet been finalized, and the HTLCs have not yet expired. Thanks to these conditions, Suzie can recover the 40,000 satoshis of the HTLC owed to her by providing s. Otherwise, Alice recovers the funds after the expiration of the timelock, because if Suzie does not know s, it means she has not transferred the 40,000 satoshis to Bob, and therefore, Alice's funds are not owed to her.

Furthermore, if the channel is closed while several HTLCs are pending, there

will be as many additional outputs as there are ongoing HTLCs. If the

channel is not closed, then after the expiration or success of the Lightning

payment, new commitment transactions are created to reflect the new, now

stable, state of the channel, that is, without any pending HTLCs. The

outputs related to the HTLCs can therefore be removed from the commitment

transactions.

Finally, in the case of a cooperative channel closure while an HTLC is active, Alice and Suzie stop accepting new payments and wait for the resolution or expiration of the ongoing HTLCs. This allows them to publish a lighter closing transaction, without the outputs related to the HTLCs, thereby reducing fees and avoiding the wait for a possible timelock.

What should you take away from this chapter?

HTLCs enable the routing of Lightning payments through multiple nodes without having to trust them. Here are the key points to remember:

- HTLCs ensure the security of payments through a secret (preimage) and an expiration time.

- The resolution or expiration of HTLCs follows a specific order: then from the destination towards the source, in order to protect each node.

- As long as an HTLC is neither resolved nor expired, it is maintained as an output in the most recent commitment transactions.

In the next chapter, we will discover how a node issuing a Lightning transaction finds and selects routes for its payment to reach the recipient node.

Finding Your Way

In the previous chapters, we saw how to use other nodes' channels to route payments and reach a node without being directly connected to it via a channel. We also discussed how to ensure the security of the transfer without trusting the intermediary nodes. In this chapter, we will focus on finding the best possible route to reach a target node.

The Problem of Routing in Lightning

As we have seen, in Lightning, it is the payment-sending node that must calculate the complete route to the recipient, because we use an onion routing system. The intermediary nodes do not know either the point of origin or the final destination. They only know where the payment comes from and to which node they must transfer it next. This means that the sending node must maintain a dynamic local topology of the network, with the existing Lightning nodes and the channels between each, taking into account openings, closures, and state updates.

Even with this topology of the Lightning Network, there is essential information

for routing that remains inaccessible to the sending node, which is the exact

distribution of liquidity in the channels at any given moment. Indeed, each channel

only displays its total capacity, but the internal

distribution of funds is only known to the two participating nodes. This

poses challenges for efficient routing, as the success of the payment

depends notably on whether its amount is less than the lowest liquidity on

the chosen route. However, the liquidities are not all visible to the

sending node.

Even with this topology of the Lightning Network, there is essential information

for routing that remains inaccessible to the sending node, which is the exact

distribution of liquidity in the channels at any given moment. Indeed, each channel

only displays its total capacity, but the internal

distribution of funds is only known to the two participating nodes. This

poses challenges for efficient routing, as the success of the payment

depends notably on whether its amount is less than the lowest liquidity on

the chosen route. However, the liquidities are not all visible to the

sending node.

Network Map Update

To keep their network map up to date, nodes regularly exchange messages through an algorithm called "gossip". This is a distributed algorithm used to spread information in an epidemic manner to all the nodes in the network, which allows for the exchange and synchronization of the global state of the channels in a few communication cycles. Each node propagates information to one or more neighbors chosen at random or not, these, in turn, propagate the information to other neighbors and so on until a globally synchronized state is achieved.

The 2 main messages exchanged between Lightning nodes are as follows:

- "Channel Announcements": messages signaling the opening of a new channel.

- "Channel Updates": update messages on the state of a channel, particularly on the evolution of fees (but not on the distribution of liquidity).

Lightning nodes also monitor the Bitcoin blockchain to detect channel closing transactions. The closed channel is then removed from the map since it can no longer be used to route our payments.

Routing a Payment

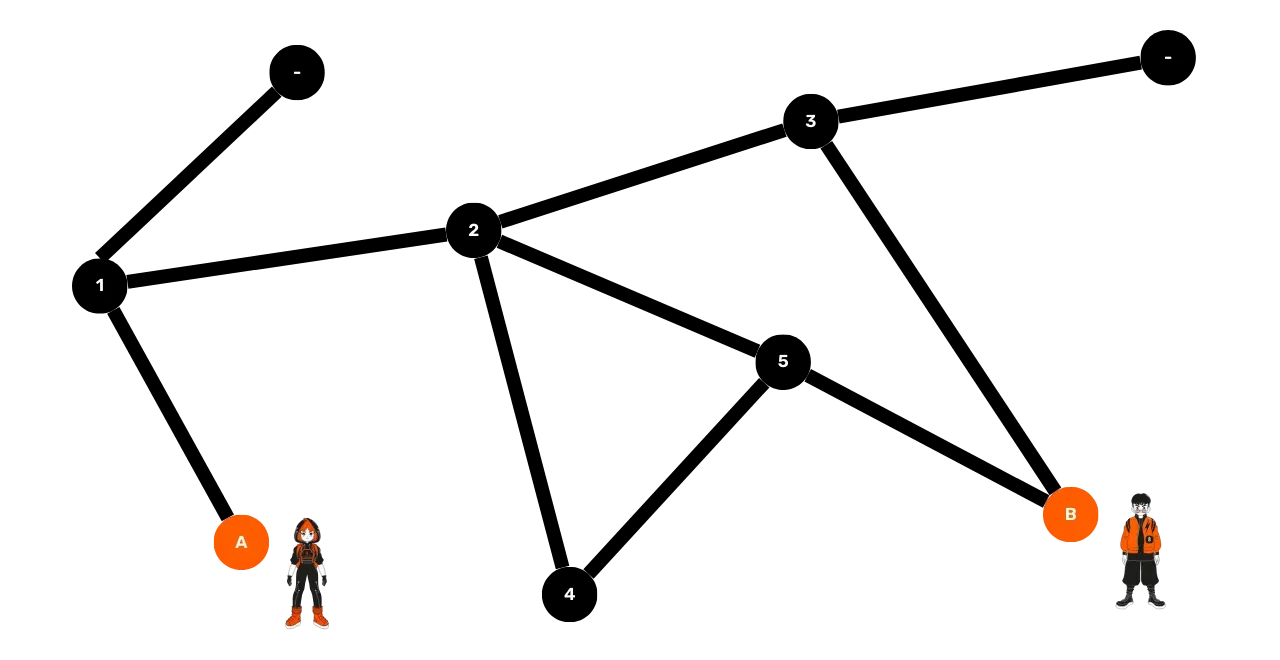

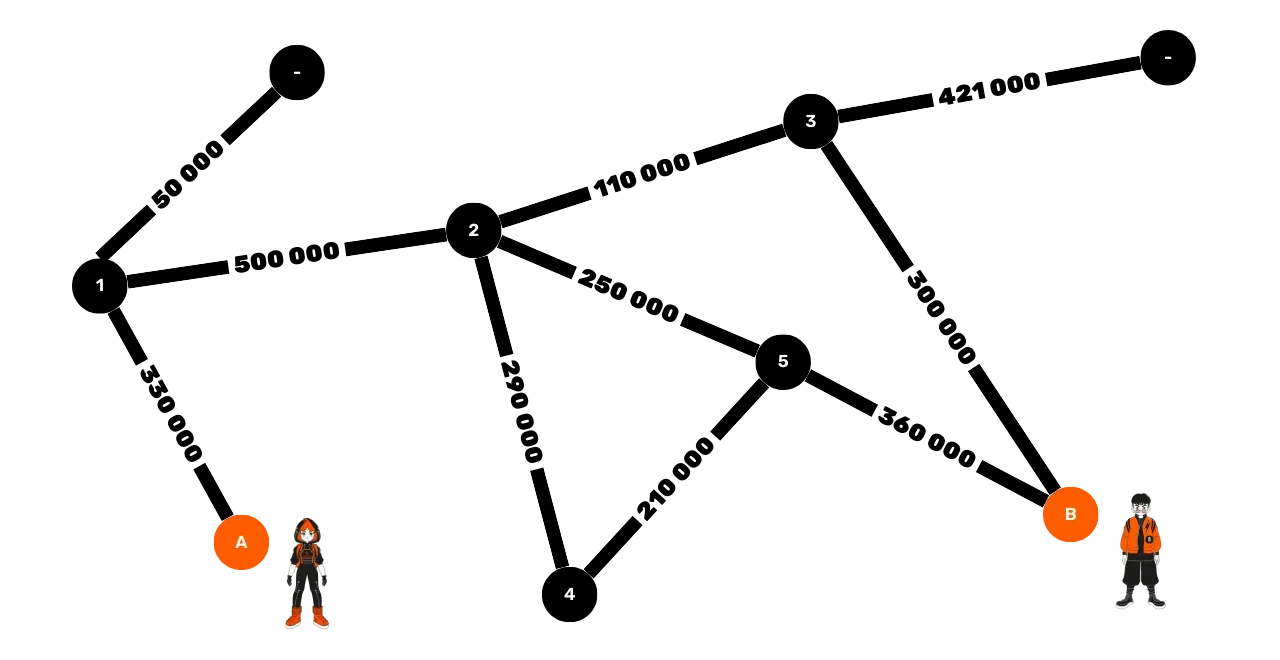

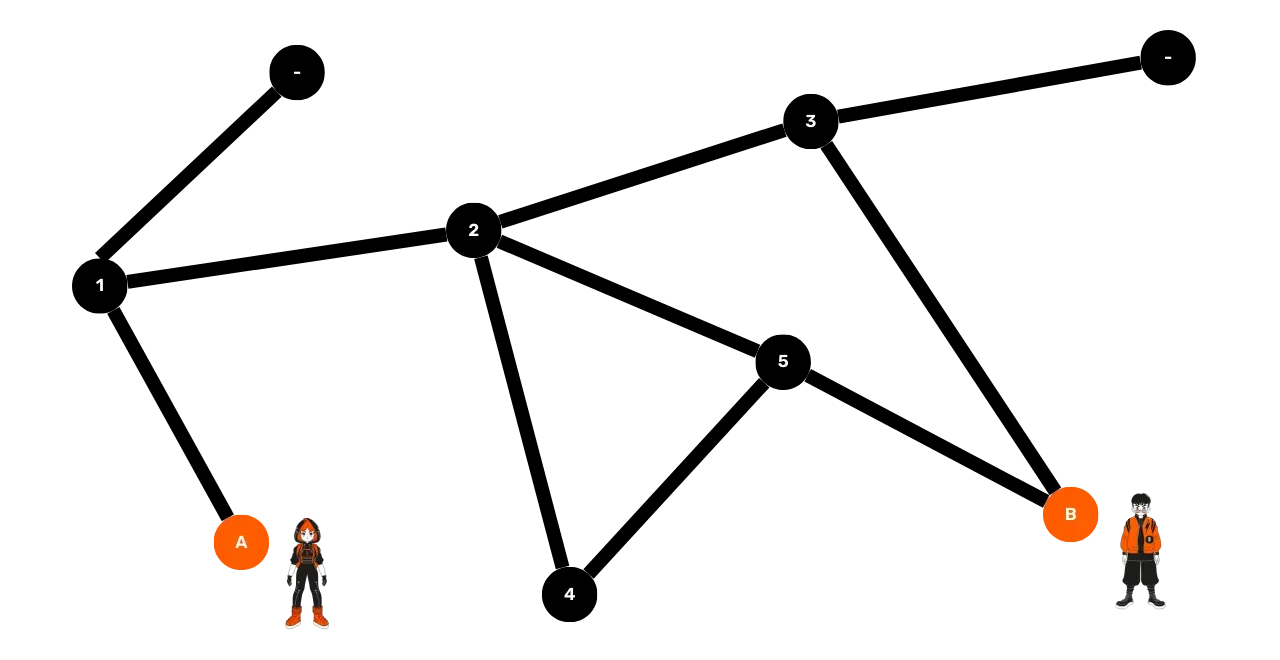

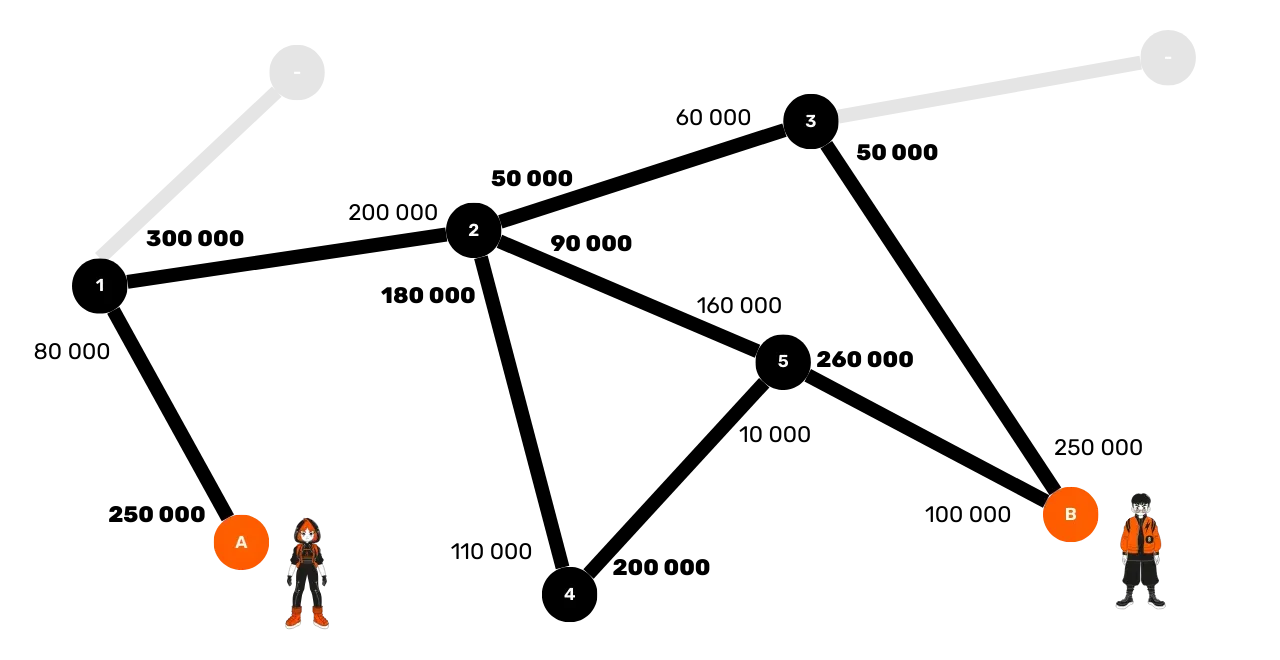

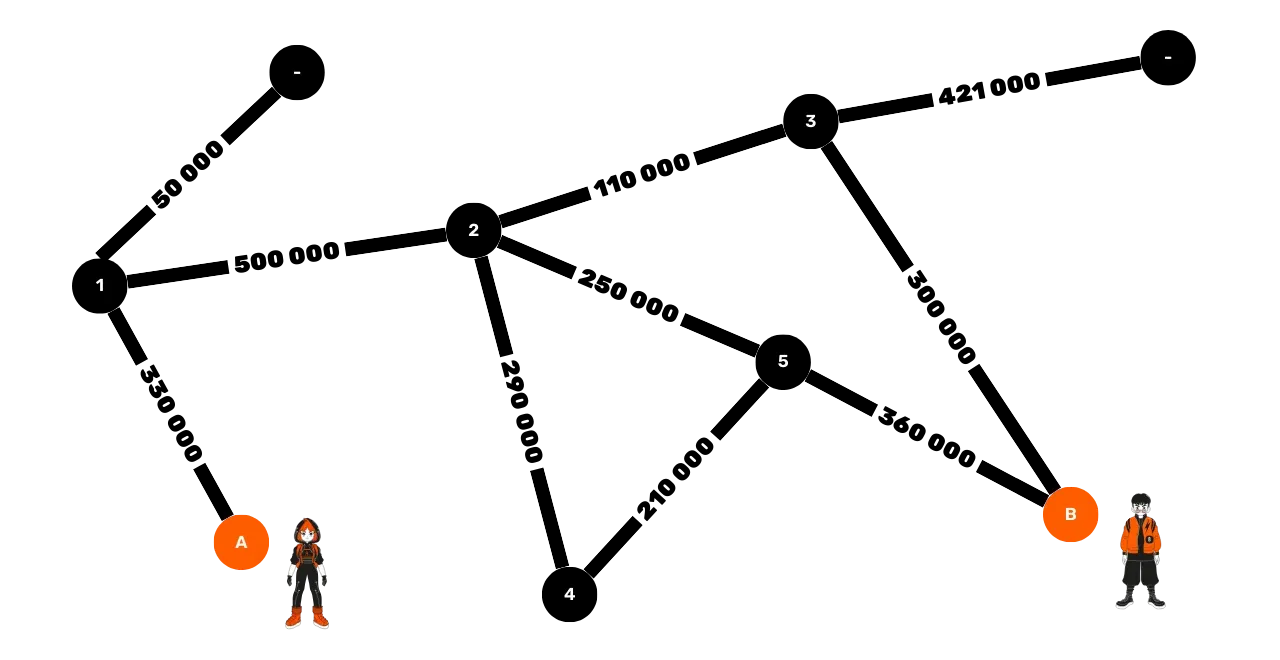

Let's take an example of a small Lightning Network with 7 nodes: Alice, Bob, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. Imagine that Alice wants to send a payment to Bob but must go through intermediary nodes.

Here is the actual distribution of funds in these channels:

- Channel between Alice and 1: 250,000 sats on Alice's side, 80,000 on 1's side (total capacity of 330,000 sats).

- Channel between 1 and 2: 300,000 sats on 1's side, 200,000 on 2's side (total capacity of 500,000 sats).

- Channel between 2 and 3: 50,000 sats on 2's side, 60,000 on 3's side (total capacity of 110,000 sats).

- Channel between 2 and 5: 90,000 sats on side 2, 160,000 on side 5 (total capacity of 250,000 sats).

- Channel between 2 and 4: 180,000 sats on side 2, 110,000 on side 4 (total capacity of 290,000 sats).

- Channel between 4 and 5: 200,000 sats on side 4, 10,000 on side 5 (total capacity of 210,000 sats).

- Channel between 3 and Bob: 50,000 sats on side 3, 250,000 on side Bob (total capacity of 300,000 sats).

- Channel between 5 and Bob: 260,000 sats on side 5, 100,000 on side Bob (total capacity of 360,000 sats).

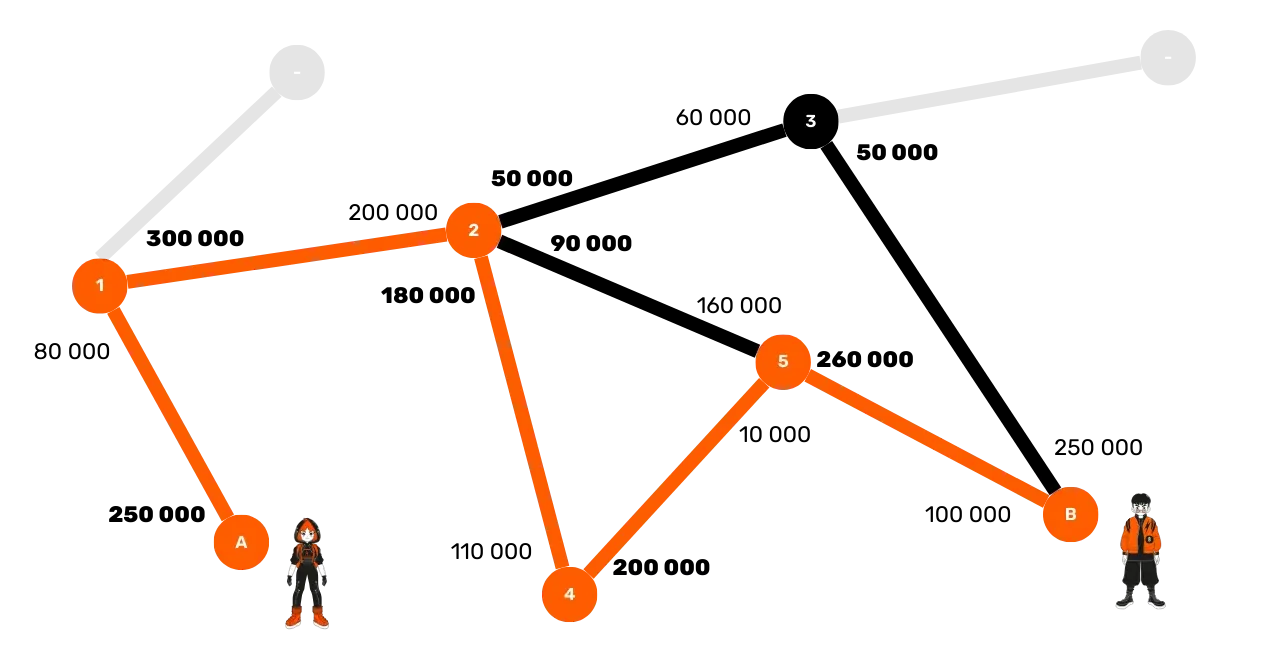

To make a payment of 100,000 sats from Alice to Bob, the routing options are

limited by the available liquidity in each channel. The optimal route for

Alice, based on the known liquidity distributions, could be the sequence Alice → 1 → 2 → 4 → 5 → Bob:

But since Alice does not know the exact distribution of funds in each channel, she must estimate the optimal route probabilistically, taking into account the following criteria:

- Probability of success: a channel with a higher total capacity is more likely to contain sufficient liquidity. For example, the channel between node 2 and node 3 has a total capacity of 110,000 sats, so it is unlikely to find 100,000 sats or more on the side of node 2, although it remains possible.

- Transaction fees: in choosing the best route, the sending node also considers the fees applied by each intermediate node and seeks to minimize the total routing cost.

- Expiration of HTLCs: to avoid blocked payments, the expiration time of HTLCs is also a parameter to consider.

- Number of intermediate nodes: finally, more broadly, the sending node will seek to find a route with the fewest possible nodes to reduce the risk of failure and limit Lightning transaction fees.

By analyzing these criteria, the sending node can test the most probable routes and attempt to optimize them. In our example, Alice could rank the best routes as follows:

Alice → 1 → 2 → 5 → Bob, because it's the shortest route with the highest capacity.Alice → 1 → 2 → 4 → 5 → Bob, because this route offers good capacities, although it is longer than the first.Alice → 1 → 2 → 3 → Bob, because this route includes the channel2 → 3, which has very limited capacity, but remains potentially usable.

Payment Execution

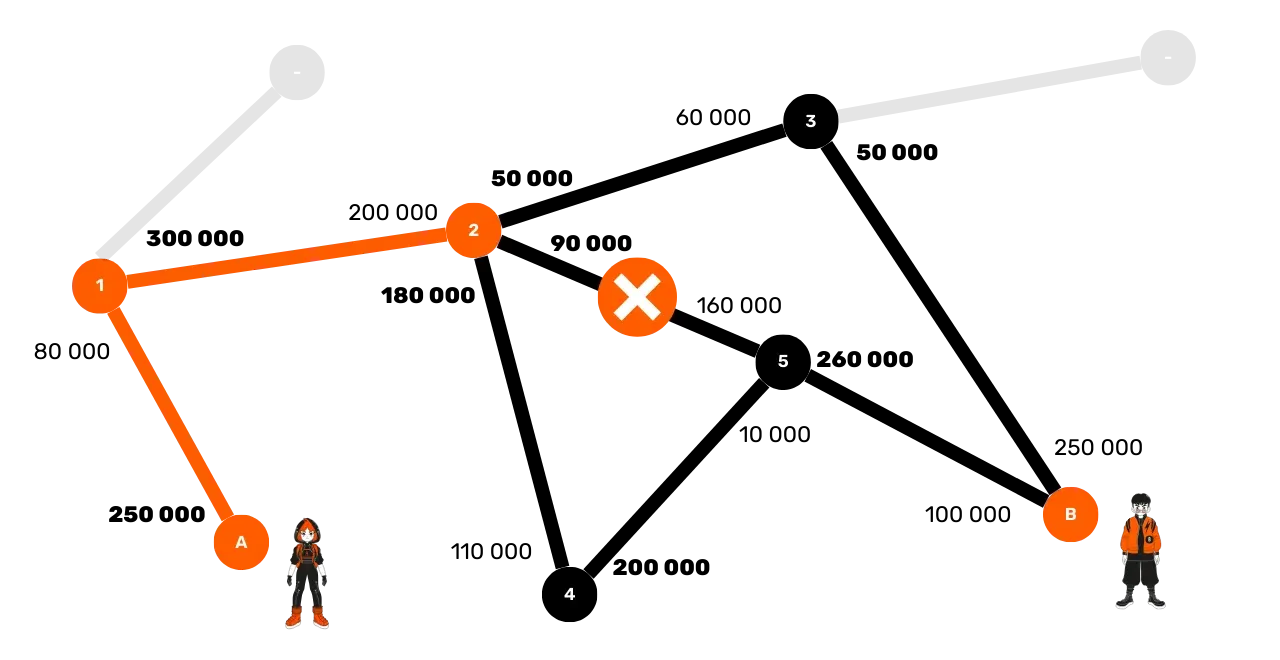

Alice decides to test her first route (Alice → 1 → 2 → 5 → Bob). She therefore sends a HTLC of 100,000 sats to node 1. This node checks

that it has sufficient liquidity with node 2, and continues the

transmission. Node 2 then receives the HTLC from node 1, but realizes it

does not have enough liquidity in its channel with node 5 to route a payment

of 100,000 sats. It then sends an error message back to node 1, who

transmits it to Alice. This route has failed.

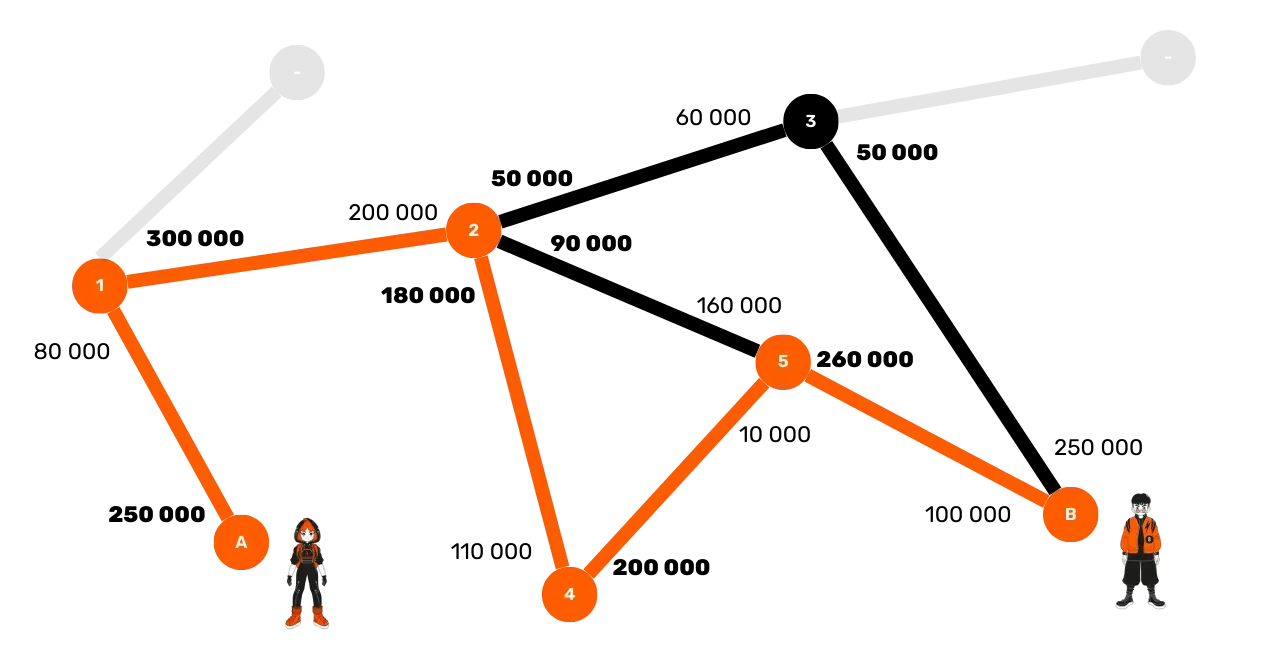

Alice then attempts to route her payment using her second route (Alice → 1 → 2 → 4 → 5 → Bob). She sends a HTLC of 100,000 sats to node 1, who transmits it to node 2,

then to node 4, to node 5, and finally to Bob. This time, the liquidity is

sufficient, and the route is functional. Each node unlocks its HTLC in

cascade using the preimage provided by Bob (the secret s), which

allows Alice's payment to Bob to be successfully finalized.

The search for a route is conducted as follows: the sending node starts by identifying the best possible routes, then attempts payments successively until a functional route is found.

It's worth noting that Bob can provide Alice with information in the invoice to facilitate routing. For example, he can indicate nearby channels with sufficient liquidity or reveal the existence of private channels. These indications allow Alice to avoid routes with little chance of success and to first attempt the paths recommended by Bob.

What should you take away from this chapter?

- Nodes maintain a map of the network topology through announcements and by monitoring channel closures on the Bitcoin blockchain.

- The search for an optimal route for a payment remains probabilistic and depends on many criteria.

- Bob can provide indications in the invoice to guide Alice's routing and save her from testing unlikely routes.

In the following chapter, we will specifically study the functioning of invoices, in addition to some other tools used on the Lightning Network.

The Tools of the Lightning Network

Invoice, LNURL, and Keysend

e34c7ecd-2327-52e3-b61e-c837d9e5e8b0 :::video id=309c3412-506e-4189-ad46-5e5088c55008:::

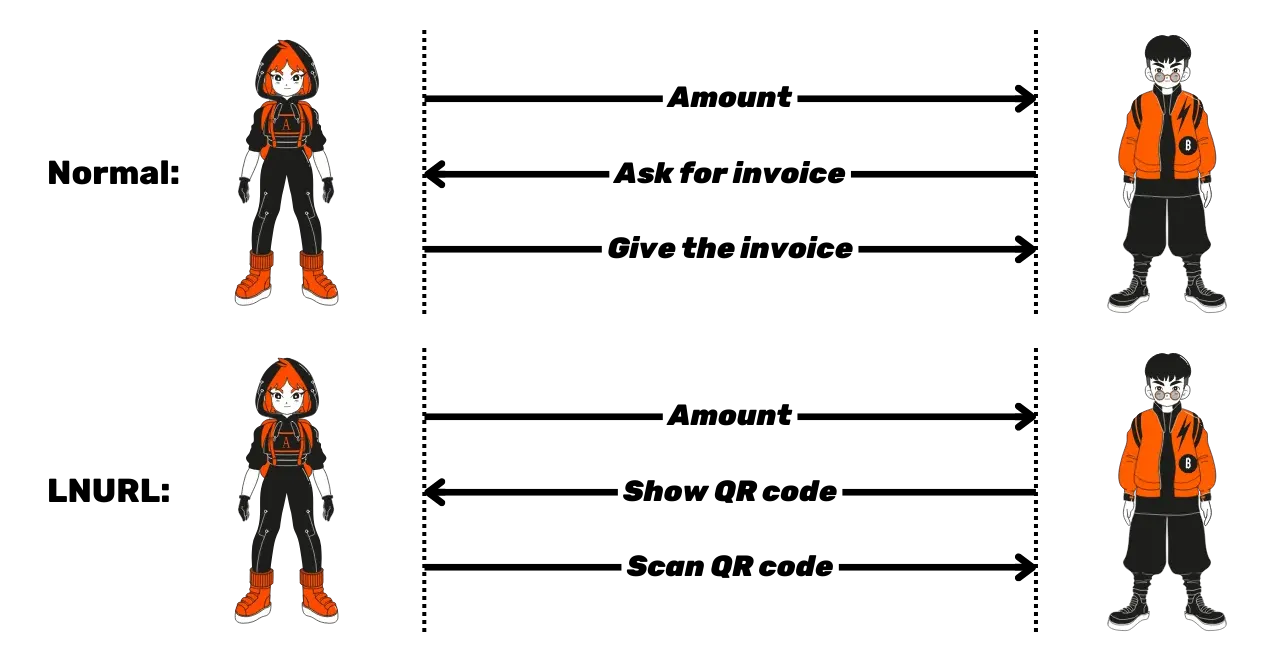

In this chapter, we will take a closer look at the operation of Lightning invoices, that is, payment requests sent by the recipient node to the sender node. The goal is to understand how to pay and receive payments on Lightning. We will also discuss 2 alternatives to classic invoices: LNURL and Keysend.

The Structure of Lightning Invoices

As explained in the chapter on HTLCs, each payment begins with the generation of an invoice by the recipient. This invoice is then transmitted to the payer (via a QR code or by copy-pasting) to initiate the payment. An invoice consists of two main parts:

- The Human Readable Part: this section contains clearly visible metadata to enhance the user experience.

- The Payload: this section includes information intended for machines to process the payment.

The typical structure of an invoice starts with an identifier ln for "Lightning", followed by bc for Bitcoin, then the amount of

the invoice. A separator 1 distinguishes the human-readable part

from the data (payload) part.

Let's take the following invoice as an example:

lnbc100u1p0x7x7dpp5l7r9y50wrzz0lwnsqgxdks50lxtwkl0mhd9lslr4rcgdtt2n6lssp5l3pkhdx0cmc9gfsqvw5xjhph84my2frzjqxqyz5vq9qsp5k4mkzv5jd8u5n89d2yc50x7ptkl0zprx0dfjh3km7g0x98g70hsqq7sqqqgqqyqqqqlgqqvnv2k5ehwnylq3rhpd9g2y0sq9ujyxsqqypjqqyqqqqqqqqqqqsqqqqq9qsq3vql5f6e45xztgj7y6xw6ghrcz3vmh8msrz8myvhsarxg42ce9yyn53lgnryx0m6qqld8fql

We can already divide it into 2 parts. First, there's the Human Readable Part:

lnbc100u

Then the part intended for the payload:

p0x7x7dpp5l7r9y50wrzz0lwnsqgxdks50lxtwkl0mhd9lslr4rcgdtt2n6lssp5l3pkhdx0cmc9gfsqvw5xjhph84my2frzjqxqyz5vq9qsp5k4mkzv5jd8u5n89d2yc50x7ptkl0zprx0dfjh3km7g0x98g70hsqq7sqqqgqqyqqqqlgqqvnv2k5ehwnylq3rhpd9g2y0sq9ujyxsqqypjqqyqqqqqqqqqqqsqqqqq9qsq3vql5f6e45xztgj7y6xw6ghrcz3vmh8msrz8myvhsarxg42ce9yyn53lgnryx0m6qqld8fql

The two parts are separated by a 1. This separator was chosen

instead of a special character to allow for easy copy-pasting of the entire

invoice by double-clicking.

In the first part, we can see that:

lnindicates that it's a Lightning transaction.bcindicates that the Lightning network is on the Bitcoin blockchain (and not on the testnet or on Litecoin).100uindicates the amount of the invoice, expressed in microbitcoins (umeaning "micro"), which here equals 10,000 sats.

To designate the payment amount, it is expressed in sub-units of bitcoin. Here are the units used:

Millibitcoin (denoted

m): Represents one-thousandth of a bitcoin.1 \, \text{mBTC} = 10^{-3} \, \text{BTC} = 10^5 \, \text{satoshis}Microbitcoin (denoted

u): Also sometimes called "bit", represents one-millionth of a bitcoin.1 \, \mu\text{BTC} = 10^{-6} \, \text{BTC} = 100 \, \text{satoshis}Nanobitcoin (denoted

n): Represents one-billionth of a bitcoin.1 \, \text{nBTC} = 10^{-9} \, \text{BTC} = 0.1 \, \text{satoshis}Picobitcoin (denoted

p): Represents one-trillionth of a bitcoin.1 \, \text{pBTC} = 10^{-12} \, \text{BTC} = 0.0001 \, \text{satoshis}

The Payload of an Invoice

The payload of an invoice includes several pieces of information necessary for processing the payment:

- The timestamp: The moment of the invoice's creation, expressed in Unix Timestamp (the number of seconds that have elapsed since January 1, 1970).

- Hashing the Secret: As we saw in the section on HTLCs, the receiving node must provide the sending node with the hash of the preimage. This is used in HTLCs to secure the transaction. We referred to it as "r".

- The Payment Secret: Another secret is generated by the recipient, but this time it is transmitted to the sending node. It is used in onion routing to prevent intermediate nodes from guessing whether the next node is the final recipient or not. This thus maintains a form of confidentiality for the recipient with respect to the last intermediate node on the route.

- The Recipient's Public Key: Indicates to the payer the identifier of the person to be paid.

- The Expiration Duration: The maximum time for the invoice to be paid (1 hour by default).

- Routing Hints: Additional information provided by the recipient to help the sender optimize the payment route.

- The Signature: Guarantees the integrity of the invoice by authenticating all the information.

The invoices are then encoded in bech32, the same format as

for Bitcoin SegWit addresses (format starting with bc1).

LNURL Withdrawal

In a traditional transaction, such as a store purchase, the invoice is generated for the total amount to be paid. Once the invoice is presented (in the form of a QR code or string of characters), the customer can scan it and finalize the transaction. The payment then follows the traditional process that we studied in the previous section. However, this process can sometimes be very cumbersome for the user experience, as it requires the receiver to send information to the sender via the invoice.

For certain situations, like withdrawing bitcoins from an online service, the traditional process is too cumbersome. In such cases, the LNURL withdrawal solution simplifies this process by displaying a QR code that the recipient's wallet scans to automatically create the invoice. The service then pays the invoice, and the user simply sees an instant withdrawal.

LNURL is a communication protocol that specifies a set of functionalities designed to simplify interactions between Lightning nodes and clients, as well as third-party applications. The LNURL withdrawal, as we have just seen, is thus just one example among other functionalities. This protocol is based on HTTP and allows the creation of links for various operations, such as a payment request, a withdrawal request, or other functionalities that enhance the user experience. Each LNURL is a bech32 encoded URL with the lnurl prefix, which, once scanned, triggers a series of automatic actions on the Lightning wallet. For example, the LNURL-withdraw (LUD-03) feature allows withdrawing funds from a service by scanning a QR code, without the need to manually generate an invoice. Similarly, LNURL-auth (LUD-04) enables logging into online services using a private key on one's Lightning wallet instead of a password.

Sending a Lightning Payment without an Invoice: Keysend

Another interesting case is the transfer of funds without having received an invoice beforehand, known as "Keysend". This protocol allows sending funds by adding a preimage in the encrypted payment data, accessible only by the recipient. This preimage enables the recipient to unlock the HTLC, thus retrieving the funds without having generated an invoice beforehand.

To simplify, in this protocol, it is the sender who generates the secret used in the HTLCs, rather than the recipient. Practically, this allows the sender to make a payment without having had to interact with the recipient beforehand.

What should you take away from this chapter?

- A Lightning Invoice is a payment request consisting of a human-readable part and a machine data part.

- The invoice is encoded in bech32, with a

1separator to facilitate copying and a data part containing all the information necessary to process the payment. - Other payment processes exist on Lightning, notably LNURL-Withdraw to facilitate withdrawals, and Keysend for direct transfers without an invoice.

In the following chapter, we will see how a node operator can manage liquidity in their channels, to never be blocked and always be able to send and receive payments on the Lightning Network.

Managing Your Liquidity

In this chapter, we will explore strategies for effectively managing liquidity on the Lightning Network. Liquidity management varies depending on the type of user and context. We will look at the main principles and existing techniques to better understand how to optimize this management.

Liquidity Needs

There are three main user profiles on Lightning, each with specific liquidity needs:

- The Payer: This is the one who makes payments. They need outgoing liquidity to be able to transfer funds to other users. For example, this could be a consumer.

- The Seller (or Payee): This is the one who receives payments. They need incoming liquidity to be able to accept payments to their node. For example, this could be a business or an online store.

- The Router: An intermediary node, often specialized in routing payments, that must optimize its liquidity in each channel to route as many payments as possible and earn fees.

These profiles are obviously not fixed; a user can switch between payer and payee depending on the transactions. For example, Bob could receive his salary on Lightning from his employer, placing him in the position of a "seller" requiring incoming liquidity. Subsequently, if he wants to use his salary to buy food, he becomes a "payer" and must then have outgoing liquidity.

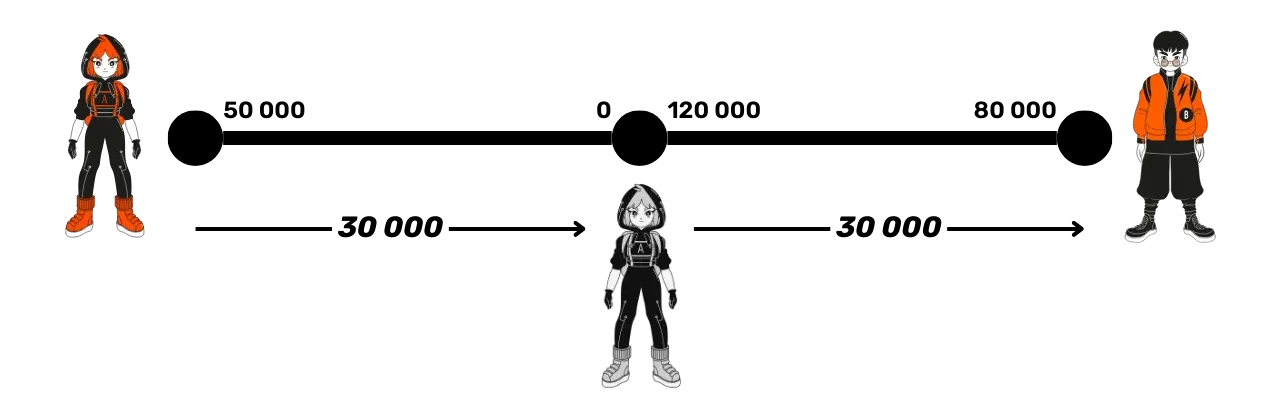

To better understand, let's take the example of a simple network composed of three nodes: the buyer (Alice), the router (Suzie), and the seller (Bob).

Imagine that the buyer wants to send 30,000 sats to the seller and that the payment goes through the router's node. Each party must then have a minimum amount of liquidity in the direction of the payment:

- The payer must have at least 30,000 satoshis on their side of the channel with the router.

- The seller must have a channel where 30,000 satoshis are on the opposite side to be able to receive them.

- The router must have 30,000 satoshis on the payer's side in their channel, and also 30,000 satoshis on their side in the channel with the seller, to be able to route the payment.

Liquidity Management Strategies

Payers must ensure to maintain sufficient liquidity on their side of the channels to guarantee outgoing liquidity. This proves to be relatively simple, as it is enough to open new Lightning channels to have this liquidity. Indeed, the initial funds locked in the multisig on-chain are entirely on the payer's side in the Lightning channel at the start. The payment capacity is thus assured as long as channels are opened with enough funds. When the outgoing liquidity is exhausted, it is enough to open new channels. On the other hand, for the seller, the task is more complex. To be able to receive payments, they must have liquidity on the opposite side of their channels. Therefore, opening a channel is not enough: they must also make a payment in this channel to move the liquidity to the other side before they can receive payments themselves. For certain Lightning user profiles, such as merchants, there is a clear disproportion between what their node sends and what it receives, since the goal of a business is primarily to collect more than it spends, in order to generate a profit. Fortunately, for these users with specific incoming liquidity needs, several solutions exist:

Attracting channels: The merchant benefits from an advantage due to the volume of incoming payments expected on their node. Taking this into account, they can try to attract routing nodes that are looking for income from transaction fees and who might open channels towards them, hoping to route their payments and collect the associated fees.

Liquidity movement: The seller can also open a channel and transfer some of the funds to the opposite side by making fictitious payments to another node, which will return the money in another way. We will see in the next part how to carry out this operation.

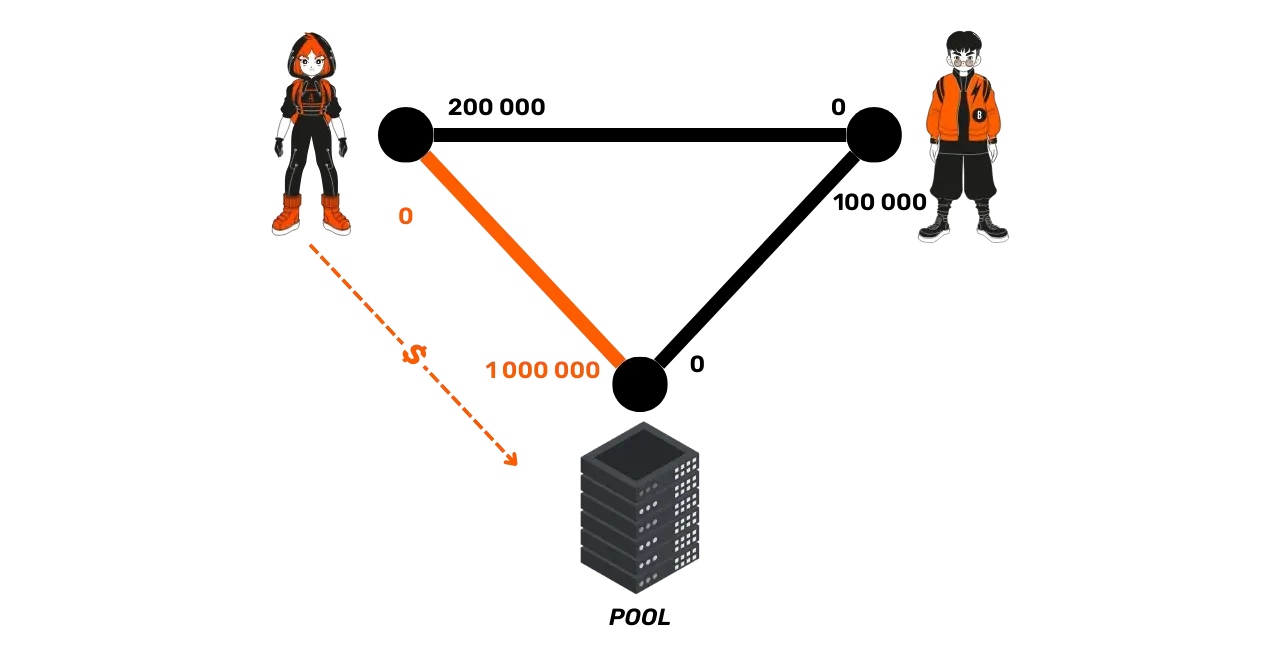

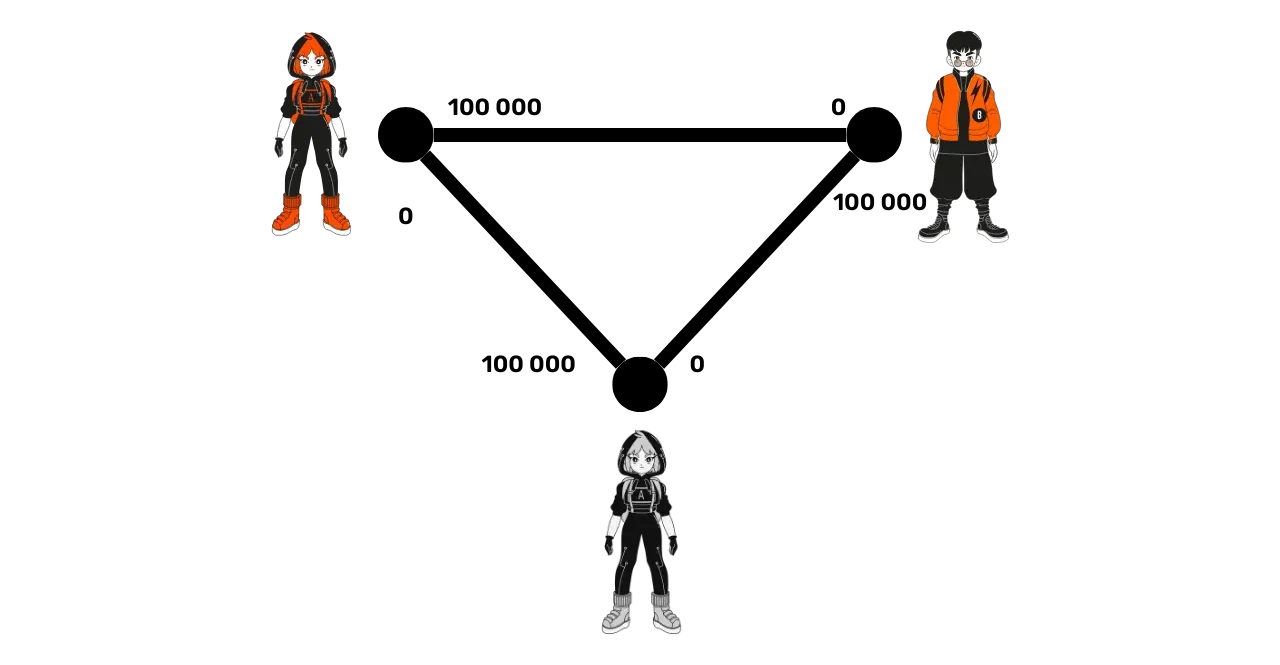

Triangular opening: Platforms exist for nodes wishing to open channels collaboratively, allowing each to benefit from immediate incoming and outgoing liquidity. For example, LightningNetwork+ offers this service. If Alice, Bob, and Suzie want to open a channel with 100,000 sats, they can agree on this platform for Alice to open a channel towards Bob, Bob towards Suzie, and Suzie towards Alice. In this way, each has 100,000 sats of outgoing liquidity and 100,000 sats of incoming liquidity, while having only locked up 100,000 sats.

- Buying channels: Services for renting Lightning channels also exist to obtain incoming liquidity, like Bitrefill Thor or Lightning Labs Pool. For example, Alice can buy a channel of one million satoshis towards her node in order to be able to receive payments.

Finally, for routers, whose goal is to maximize the number of payments processed and the fees collected, they must:

- Open well-funded channels with strategic nodes.

- Regularly adjust the distribution of funds in the channels according to the network's needs.

The Loop Out Service

The Loop Out service, offered by Lightning Labs, allows for moving liquidity to the opposite side of the channel while reclaiming the funds on the Bitcoin blockchain. For example, Alice sends 1 million satoshis via Lightning to a loop node, which then returns those funds to her in on-chain bitcoins. This balances her channel with 1 million satoshis on each side, optimizing her capacity to receive payments.

Therefore, this service enables incoming liquidity while reclaiming one's bitcoins on-chain, which helps to limit the immobilization of cash needed to accept payments with Lightning.

What should you take away from this chapter?

- To send payments on Lightning, you must have enough liquidity on your side in your channels. To increase this sending capacity, simply open new channels.

- To receive payments, you need to have liquidity on the opposite side in your channels. Increasing this receiving capacity is more complex, as it requires others to open channels towards you, or to make (fictitious or real) payments to move the liquidity to the other side.

- Maintaining liquidity where desired can be even more challenging depending on the use of the channels. That's why tools and services exist to help balance the channels as desired.

In the next chapter, I propose to review the most important concepts of this training.

Go Further

Course Summary

In this final chapter marking the end of the LNP201 training, I propose to revisit the important concepts we have covered together.

The goal of this training was to provide you with a comprehensive and technical understanding of the Lightning Network. We discovered how the Lightning Network relies on the Bitcoin blockchain to perform off-chain transactions, while retaining the fundamental characteristics of Bitcoin, notably the absence of the need to trust other nodes.

Payment Channels

In the initial chapters, we explored how two parties, by opening a payment channel, can conduct transactions outside of the Bitcoin blockchain. Here are the steps covered:

- Channel Opening: The creation of the channel is done through a Bitcoin transaction that locks the funds in a 2/2 multisignature address. This deposit represents the Lightning channel on the blockchain.

2. Transactions in the Channel: In this channel, it is then

possible to carry out numerous transactions without having to publish them

on the blockchain. Each Lightning transaction creates a new state of the

channel reflected in a commitment transaction.

2. Transactions in the Channel: In this channel, it is then

possible to carry out numerous transactions without having to publish them

on the blockchain. Each Lightning transaction creates a new state of the

channel reflected in a commitment transaction.

- Securing and Closing: Participants commit to the new state of the channel by exchanging revocation keys to secure the funds and prevent any cheating. Both parties can close the channel cooperatively by making a new transaction on the Bitcoin blockchain, or as a last resort through a forced closure. This latter option, although less efficient because it is longer and sometimes poorly evaluated in terms of fees, still allows for the recovery of funds. In case of cheating, the victim can punish the cheater by recovering all the funds from the channel on the blockchain.

The Network of Channels

After studying isolated channels, we extended our analysis to the network of channels:

- Routing: When two parties are not directly connected by a channel, the network allows for routing through intermediary nodes. Payments then transit from one node to another.

- HTLCs: Payments transiting through intermediary nodes are secured by "Hash Time-Locked Contracts" (HTLC), which allow for the funds to be locked until the payment is completed end-to-end.

- Onion Routing: To ensure the confidentiality of the payment, onion routing masks the final destination to intermediary nodes. The sending node must therefore calculate the entire route, but in the absence of complete information on the liquidity of the channels, it proceeds through successive trials to route the payment.

Liquidity Management

We have seen that liquidity management is a challenge on Lightning to ensure the smooth flow of payments. Sending payments is relatively simple: it just requires opening a channel. However, receiving payments requires having liquidity on the opposite side of one's channels. Here are some strategies discussed:

Attracting Channels: By encouraging other nodes to open channels towards oneself, a user obtains incoming liquidity.

Moving Liquidity: By sending payments to other channels, liquidity moves to the opposite side.

- Using Services like Loop and Pool: These services allow

for rebalancing or buying channels with liquidity on the opposite side.

- Collaborative Openings: There are also platforms available for connecting to perform triangular openings and to have incoming liquidity.

Final Section

Reviews & Ratings

38814c99-eb7b-5772-af49-4386ee2ce9b0 true

Final exam

7ed33400-aef7-5f3e-bfb1-7867e445d708 true

Conclusion

afc0d72b-4fbc-5893-90b2-e27fb519ad02 true