name: The History of Bitcoin's Creation goal: Discover the history of the origins, launch, and early developments of Bitcoin. objectives:

- Understand the technical context in which Bitcoin emerged

- Grasp how Bitcoin was designed by Satoshi Nakamoto

- Know the events that marked the launch of the system and its development

A Dive into the History of Bitcoin's Creation

Welcome to this course dedicated to the history of Bitcoin's creation! As a user, you might have wondered where the tool you are using comes from. Moreover, you may not understand the references sometimes made to the people and events that have marked the short history of cryptocurrency. Finally, studying this history will allow you to better understand Bitcoin itself, by exposing the context that shaped its slow formation.

In this course, you will discover the journey of its design, launch, and initial economic construction. In the first part, we will look at the technical context in which the concept of Bitcoin emerged. In the second part, we will focus on its birth and bootstrapping. In the third part, we will study how Bitcoin gained magnitude in terms of economic use, mining production, and software development. In the fourth part, we will simply follow how Satoshi Nakamoto, the creator of Bitcoin, gradually disappeared and how the community took over, making cryptocurrency a truly collective project.

This course is, of course, centered on the figure of Satoshi Nakamoto, whose words and actions you will discover, but it also involves other characters who participated in the development of Bitcoin during its first years of existence. You will thus get to know individuals like Hal Finney, Martti Malmi, Laszlo Hanyecz, Gavin Andresen, Jeff Garzik, or Amir Taaki, who were essential pioneers in this growth. We hope that this dive into the history of Bitcoin's beginnings will be beneficial to you!

Introduction

Course overview

85290407-1aa3-4cb4-890a-aed23441afb7 Welcome to the HIS201 course! This course aims to tell you the story of the creation of Bitcoin in a way you've never read before. It is often overlooked, despite being filled with fascinating details. We will endeavor to describe it in all its complexity, from its conception by Satoshi Nakamoto to his early disappearance and the handover to the community.

Brief Overview

Bitcoin was designed by an individual (or a group) using the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto. On October 31, 2008, he shared a white paper describing his model via an obscure email mailing list on the Internet. On January 8, 2008, he implemented his concept by publishing the software's source code and launching the network by mining the first blocks of the chain. Eager to attract a critical number of users, he promoted his creation across various communication channels.

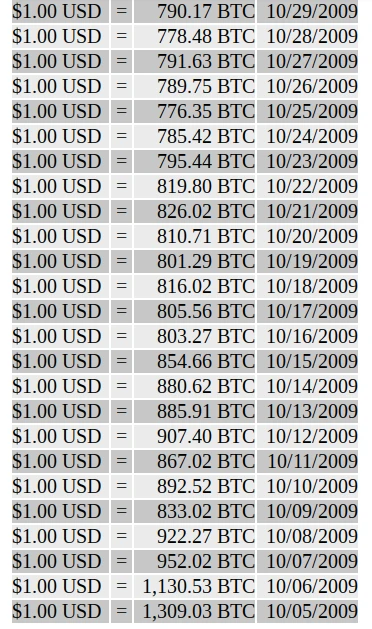

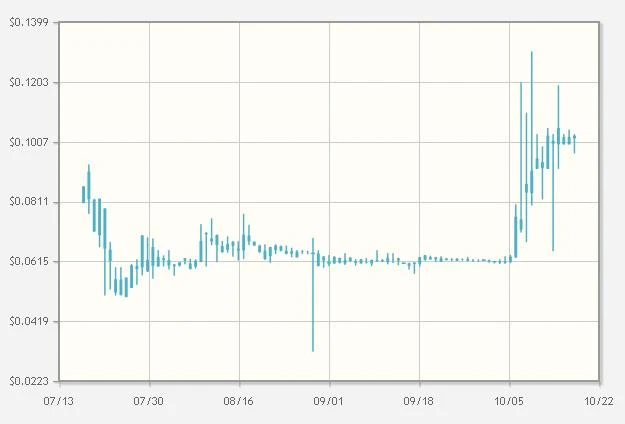

After a difficult start, the system's bootstrapping finally took place in October 2009, when the unit of account – also called bitcoin – gained a price. The first merchant services began to appear at the beginning of 2010, starting with exchange services that bridged to the dollar. It was also around this time that mining with a graphics card, more efficient, was initially implemented, and the first exchange for a physical good, specifically a pizza, took place, following the initiative of Laszlo Hanyecz.

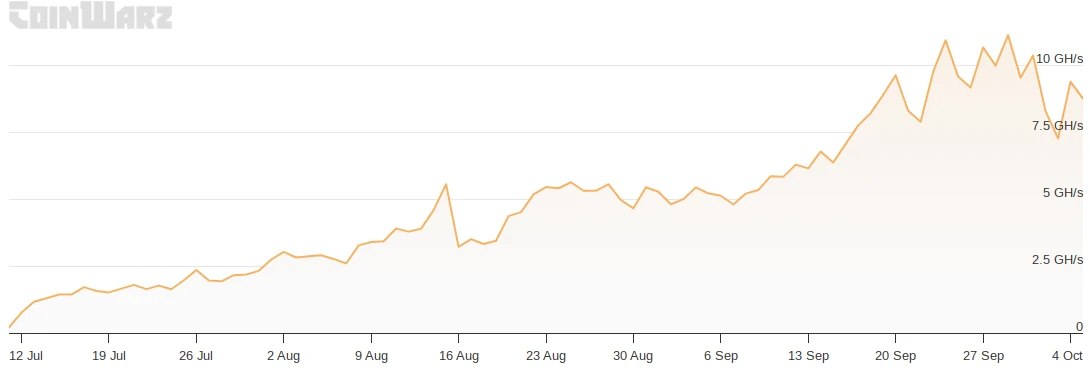

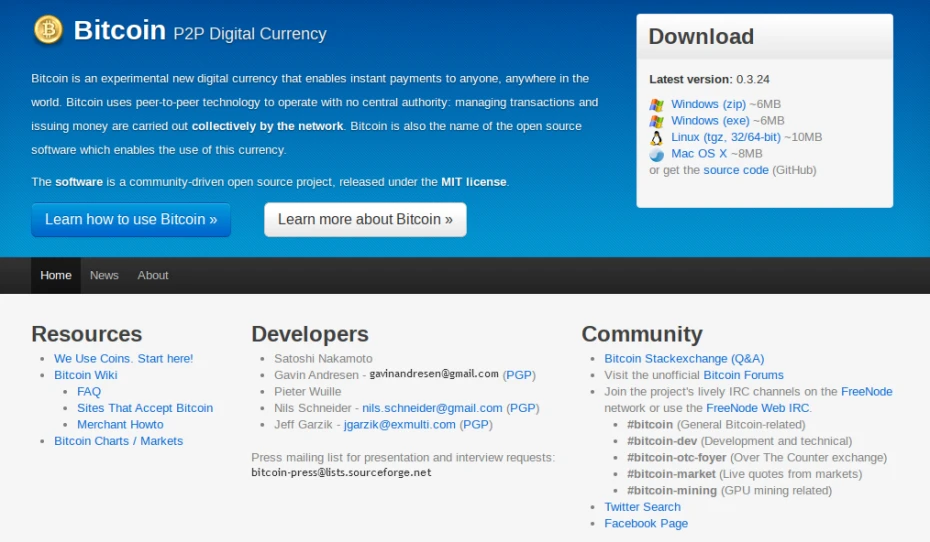

The project really took off during the summer of 2010, following the publication of an article on the very popular site Slashdot. The exchange with the dollar, Bitcoin mining, and the software development significantly improved during this period. From the fall, Satoshi Nakamoto gradually began to withdraw, stopping public writing and gradually delegating his tasks. He eventually disappeared completely in the spring of 2011, after handing over his access to his right-hand men, Martti Malmi and Gavin Andresen. The community finally took over and managed to carry the project to what it is today.

Besides this narrative, Bitcoin also has a prehistory. Indeed, it is not an object that came out of nowhere. Its creation is part of a specific context: the search for a way to transcribe the properties of cash into cyberspace. In particular, the technical elements that compose it are the result of decades of research and experimentation that preceded it. Bitcoin is based on:

- Digital signature, stemming from asymmetric cryptography born in 1976;

- Distributed consensus, developed in the 1980s following the early developments of the Internet;

- Document timestamping, invented in the early 90s with the emergence of the first strong hash functions;

- Proof of work, described and implemented during the 90s.

In designing Bitcoin, Satoshi Nakamoto was greatly inspired by the eCash model, a concept proposed by cryptographer David Chaum in 1982 and implemented through his company DigiCash in the 90s. This model, which relied on the blind signature process, allowed users to make exchanges in a relatively confidential manner. However, it was based on a centralized network of banks that intervened to prevent double spending. Therefore, when DigiCash went bankrupt, the system collapsed. Bitcoin corrected this problem by eliminating the need for a trusted third party.

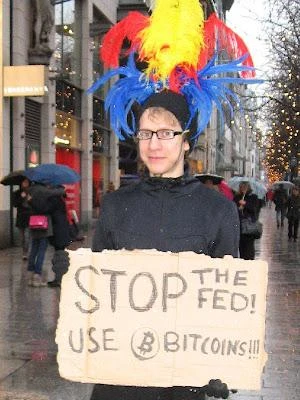

Bitcoin emerged in a particular context: the closure by the U.S. federal government of private currency systems, such as the digital gold currency e-gold in 2008 and the Liberty Reserve system in 2013. By relying on a model that distributed risk among its participants, similar to peer-to-peer sharing systems like BitTorrent, Satoshi Nakamoto created a robust model of digital currency that could withstand direct assaults from the state.

The creation of Bitcoin was also in the context of the state closure of private currency systems such as e-gold and Liberty Reserve. It constituted a robust model of digital currency that could resist direct assaults from the U.S. federal government. By distributing risk among its participants, similar to peer-to-peer sharing systems like BitTorrent, it ensured its own survival.

Finally, the Bitcoin project is the heir to the ethos of the cypherpunk movement, a movement of rebel cryptographers from the 90s, who sought to preserve the privacy and freedom of people on the Internet through the proactive use of cryptography. Bitcoin is in line with projects like b-money, bit gold, or RPOW imagined by these individuals at the end of the 90s and the beginning of the 2000s. Satoshi Nakamoto mentioned them, although he was not aware of them before designing Bitcoin and probably was not part of the original movement.

Course Outline

This course is divided into four parts, which respectively focus on the origins of Bitcoin (3 chapters), its slow emergence (3 chapters), its initial rise (3 chapters), and the formation of its community (4 chapters). In total, it includes 12 chapters which are as follows (the concerned period is also specified):

- eCash: Chaumian electronic cash (1976–1998)

- Private Digital Currencies (1996–2013)

- Decentralized Models Before Nakamoto (1982–2012)

- The Birth of Bitcoin (August 2008–Jan. 2009)

- Presentation to the World (Jan. 2009–Oct. 2009)

- The Bootstrapping of Cryptocurrency (Oct. 2009–Apr. 2010)

- Graphics Cards, Pizzas, and Free Bitcoins (Apr. 2010–June 2010)

- The Great Slashdotting (June 2010–July 2010)

- The First Technical Troubles (July 2010–Sept. 2010)

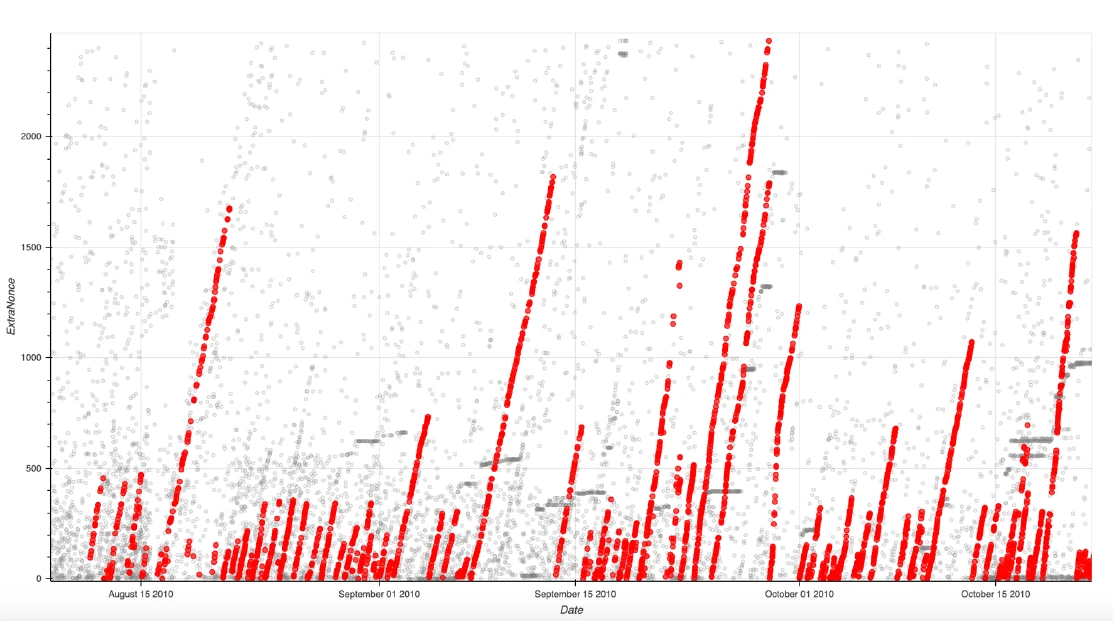

- The Digital Gold Rush (Sept. 2010–Oct. 2010)

- The Blossoming of the Ecosystem (Oct. 2010–Dec. 2010)

- The Disappearance of Satoshi (Dec. 2010–Apr. 2011)

- The Community Takes Over (Apr. 2011–Sept. 2011)

Details

All dates and times are given according to the UTC time zone (corresponding to the Greenwich Meridian) and may thus differ from American dates. It is likely that Satoshi Nakamoto was in the United States when working on his project. However, Bitcoin is an international project, which notably included contributions from Finnish developer Martti Malmi (Eastern European Time, UTC+2 / UTC+3), and we will therefore refer to the universal time zone. Thus, we say that the effective launch of the main network took place on January 9 at 2:54 AM, rather than January 8 at 6:54 PM, which corresponds to the East Coast time zone (Pacific Time, UTC-8 / UTC-7).

The content is partially adapted from the French book L'Élégance de Bitcoin (2024), written by the author of this course. In addition to direct sources archived on the Internet, we rely on a number of reference works. Here are the main ones:

- The Genesis Book by Aaron van Wirdum, published in 2024;

- Digital Gold by Nathaniel Popper, published in 2014;

- The Book of Satoshi by Phil Champagne, published in 2014;

- Digital Cash by Finn Brunton, published in 2019;

- This Machine Kills Secrets by Andy Greenberg, published in 2012.

Note that for non-English version of this course, most quotes come from American English and have been translated for the occasion. The term coin is generally translated as "unit" (and not "piece") when it refers to the unit of account.

Ready to explore the incredible saga of Bitcoin's creation? Then let’s dive together into this extraordinary story!

The Origins of Bitcoin

eCash: Chaumian Digital Cash

Before delving into the actual story of Bitcoin's creation by Satoshi Nakamoto, it is appropriate to discuss what preceded it. We will address the topic in three stages: first, we will introduce the concept of Chaumian digital cash commonly called eCash; then, we will talk about private currencies based on centralized systems such as e-gold; finally, we will describe the technical models that were imagined before the implementation of the robust distributed system that is Bitcoin.

Let's start with the first concept, eCash. eCash stems from the work of David Chaum, an American computer scientist and cryptographer born in 1955, considered a pioneer in the field of anonymous communications and a forerunner of the cypherpunks. He made a major contribution to the development of cryptography in the 1980s. He developed his model of digital cash (known as "Chaumian") at the same time and attempted to implement it in the 1990s through his company DigiCash.

David Chaum's action followed a conceptual revolution: the unveiling of asymmetric cryptography in 1976 by Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman. The idea of digital currency also emerged from this seminal discovery. Besides concealing the information contained in a message, asymmetric cryptography allowed the establishment of signature processes. It thus became possible for a person to mathematically prove that they were the owner of a certain amount of digital account units.

In this chapter, we will study what asymmetric cryptography has contributed, how David Chaum used it to design eCash, and how his concept was subsequently implemented.

The Emergence of Modern Cryptography

Cryptography is the discipline aimed at securing communication in the presence of malicious third parties by ensuring the confidentiality, authenticity, and integrity of the transmitted information. For centuries, the sole method of concealing the content of a message involved a type of encryption that relied on a unique key for both encrypting and decrypting the message. This is known as symmetric cryptography. The Caesar cipher, which involves replacing each letter in a text with another letter a fixed distance away in the alphabet, is the most well-known example (the chosen distance then becomes the key). With the development of telecommunications and the construction of the first calculating machines and computers during the 20th century, encryption algorithms have become significantly more complex. However, even though this type of cryptography works very well, it has one major drawback: the need to exchange the key in a secure manner before communication can take place.

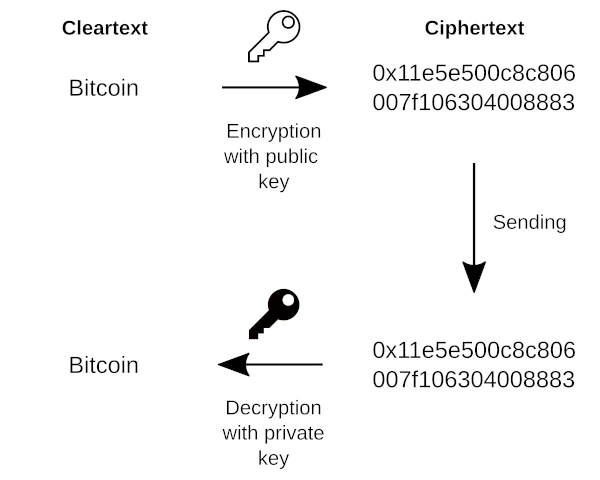

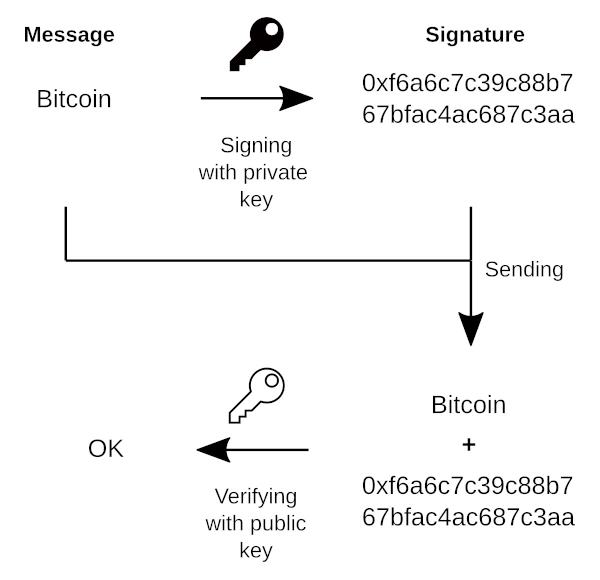

To solve this problem, asymmetric cryptography, also known as public key cryptography, was developed. It relies on two distinct keys: a private key, which is supposed to remain secret, and a public key, which is derived from the private key. Theoretically, the private key cannot be easily found from the public key, which means the latter can be shared with everyone without concern.

This type of cryptography allows for the implementation of both encryption algorithms and signature processes. Asymmetric encryption involves using the public key as an encryption key and the private key as a decryption key. The user generates a pair of keys, keeps the private key, and shares the public key with their correspondents so they can send messages. This type of encryption is analogous to a mailbox that the recipient uses to receive letters and of which only they possess the key.

Digital signatures, on the other hand, rely on using the private key as a signature key and the public key as a verification key. The user generates a pair of keys, signs a message with the private key, and sends it to their correspondents, who can verify its authenticity using the public key. Thus, they never need to know the private key.

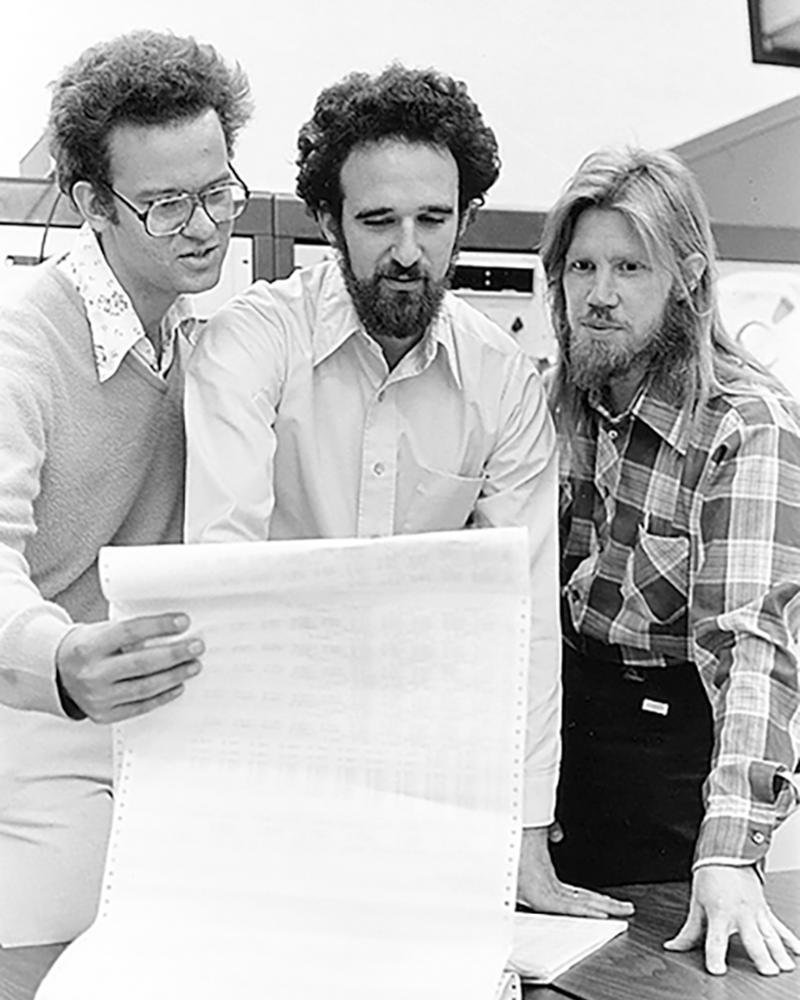

Asymmetric cryptography was independently discovered by several researchers during the 1970s. However, the first to present what they had found were Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman, two cryptographers from Stanford University. In November 1976, they published a paper titled "New Directions in Cryptography" in the journal IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, which described a key exchange algorithm (intended for the transmission of secret keys for symmetric encryption) as well as a digital signature process. In the introduction of this paper, they wrote:

"We stand today on the brink of a revolution in cryptography. The development of cheap digital hardware has freed it from the design limitations of mechanical computing and brought the cost of high-grade cryptographic devices down to where they can be used in commercial applications such as remote cash dispensers and computer terminals. In turn, such applications create a need for new types of cryptographic systems which minimize the necessity of secure key distribution channels and supply the equivalent of a written signature. At the same time, theoretical developments in information theory and computer science show promise of providing provably secure cryptosystems, changing this ancient art into a science."

Here is a photograph from 1977, taken by Chuck Painter for the Stanford News Service, where you can see Whitfield Diffie (on the right) and Martin Hellman (in the center). The person on the left is the cryptographer Ralph Merkle, who was on the verge of making the same discovery.

The article by Diffie and Hellman paved the way for a multitude of innovations. One of these was the RSA cryptosystem, which was designed in 1977 by cryptographers Ronald Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman (who gave it their names) and patented by MIT in 1983. This system allows both the encryption and signing of messages, thanks to the interchange of the roles of the keys. RSA was publicly presented for the first time in an article by Martin Gardner published in the magazine Scientific American in August 1977, which was titled "Mathematical Games: A new kind of cipher that would take millions of years to break."

The discovery of asymmetric cryptography also motivated the creation of one-way functions, characterized by making the calculation of an image (forward direction) very easy and obtaining a pre-image (reverse direction) very difficult. In particular, it led to the development of the first cryptographic hash functions, which transformed a variable-size message into a fixed-size digest. Between 1989 and 1991, several hashing algorithms (MD2, MD4, and MD5) were thus designed by Ronald Rivest for MIT.

The basic cryptographic elements of Bitcoin stem from this research. The ECDSA signature scheme, allowing the authorization of spending a traditional transaction, was created in 1992 for NIST. The SHA-256 hash function, used in multiple places in the protocol, was published in 2001 as part of the SHA-2 algorithm suite made public by the NSA. For more information on this topic, you can refer to the course Crypto 301 presented by Loïc Morel.

Blind Signatures and Electronic Cash

This revolution in the field of cryptography also inspired the young David Chaum, a computer scientist from the West Coast and then a doctoral student at the University of Berkeley. He quickly became passionate about privacy protection. He was indeed very concerned about the future of freedom and confidentiality in a society that was becoming increasingly computerized.

David Chaum in the 90s (source: Elixxir)

David Chaum in the 90s (source: Elixxir)

In his foundational article, "Security Without Identification: Transaction Systems to Make Big Brother Obsolete" published in 1985 in Communications of the ACM, he wrote:

"The foundation is being laid for a dossier society, in which computers could be used to infer individuals' life-styles, habits, whereabouts, and associations from data collected in ordinary consumer transactions. Uncertainty about whether data will remain secure against abuse by those maintaining or tapping it can have a 'chilling effect,' causing people to alter their observable activities. As computerization becomes more pervasive, the potential for these problems will grow dramatically."

This obsession with privacy protection explains his interest in the field of cryptography, to which he contributed as early as 1979. In 1981, he described the foundations of anonymous communication through mix networks, which would notably serve email relay services (Mixmaster) and the Tor anonymous network. In 1982, he participated in the founding of the International Association for Cryptologic Research (IACR) at the annual CRYPTO '82 conference. That same year (and this is what interests us here), in an article titled "Blind Signature for Untraceable Payments" he published the blind signature process, which is at the heart of his privacy-respecting digital currency model: eCash.

As David Chaum explained in a press release in 1996:

"Ecash is a digital form of cash that works on the Internet where paper cash can't. Like cash, it offers consumers true privacy in what they buy."

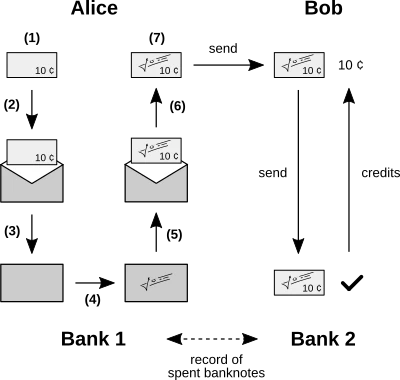

The eCash model is a digital currency concept that allows customers to make payments that are relatively confidential. It is a form of cash, in the sense that users can hold digital notes directly, rather than in an account managed by a trusted third party. However, the system relies on servers, called banks or mints, which issue and replace users' notes with each transaction. When a note is transferred, the recipient sends it to their bank, which is responsible for verifying it and giving them one or more others in return. The banks each maintain a register of spent notes to prevent double spending. Each eCash system is overseen by a central authority that issues authorizations.

Digital notes can be issued without guarantee or can be backed. In the first case, they form a base currency that must acquire value in itself. In the second case, they are backed by another currency (typically the dollar), and the user can return their notes to their bank at any time to recover the corresponding amount.

In its technical operation, the eCash model is based on the blind signature process, which allows a signer to sign something without seeing what they are signing. Each note is generated by a user, then signed by a bank to ensure its authenticity, without the bank being able to identify the note. Each note represents a specific amount of monetary units (denomination), and each bank in the system has a private key to sign each type of denomination. The mathematical procedure involved (which we will not describe here) is analogous to the signing of a physical note on carbon paper placed in a sealed envelope.

Here is an illustration of the different steps involved in the creation and replacement of a Chaumian note (from L'Élégance de Bitcoin):

The actions (each corresponding to a mathematical operation or an information transmission) are as follows:

- A user named Alice creates a carbon paper note;

- She places it in a sealed envelope;

- Alice sends the envelope containing her note to the bank and communicates the desired denomination;

- The bank signs the envelope indicating the quantity of units the note represents, which has the effect of signing the carbon paper note inside;

- The bank returns the envelope to Alice;

- Alice opens the envelope to retrieve her signed note.

- It verifies that the bank's signature is authentic. The transfer of the signed note is done by giving it to another user of the system whom we will call Bob. The steps are as follows:

- Alice sends the note to Bob;

- Bob verifies that it has indeed been signed by Alice's bank;

- He immediately sends the received note to his bank;

- Bob's bank checks that the note has not already been used and, if so, signs a new note or credits Bob's account (if there is backing).

All this implies that no bank in the system can link the payment to Alice's identity, which explains why we talk about customer confidentiality. The merchant (here, Bob) is, however, obliged to go through a bank to confirm the payment, and his bank can therefore be aware of the amounts received. Moreover, the system depends on a trusted third party – the central authority that designates the participating banks – which makes it fragile by design.

Implementations of eCash

In 1990, David Chaum founded his own company, DigiCash B.V., to implement his idea of electronic cash. This company was based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and held the patents for his invention. At that time, the Internet was still in its infancy (the Web was still under development) and e-commerce did not exist; thus, the eCash model constituted a formidable opportunity.

However, it was not David Chaum's company that first tested the model: it was the cypherpunks who implemented it without regard for the patents and who did not ask for permission to do so. Thus, a protocol named Magic Money was proposed on the cypherpunks mailing list on February 4, 1994, by an anonymous developer going by the name Pr0duct Cypher. This protocol allowed for the creation of one's own currency by operating an email server that served as an eCash mint. The cypherpunks had fun with it, creating all sorts of units of account like Tacky Tokens, GhostMarks, DigiFrancs, and NexusBucks. However, the utility of these tokens was minimal, and exchanges were very rare. On the side of DigiCash, after a few years of development, a prototype was presented in May 1994 at the first international conference on the World Wide Web at CERN in Geneva. The company then conducted a trial that began on October 19 of that year, with the issuance of units called "CyberBucks" which were not backed by any other currency. Various merchants accepted CyberBucks as part of this experiment. The cypherpunks also took to it, using it to conduct real exchanges. Thus, CyberBucks acquired value on the market. However, this value collapsed when eCash was deployed in the traditional banking system.

Photo (blurry) of the DigiCash team in 1995: David Chaum is on the far left (source: Chaum.com)

Photo (blurry) of the DigiCash team in 1995: David Chaum is on the far left (source: Chaum.com)

The introduction of eCash into the banking system began in October 1995 with the start of DigiCash's partnership with Mark Twain Bank, a small bank in Missouri. Unlike the case of CyberBucks whose exchange rate was floating, the unit of account was backed by the US dollar. Between 1996 and 1998, six banks followed Mark Twain Bank: Merita Bank in Finland, Deutsche Bank in Germany, Advance Bank in Australia, Bank Austria in Austria, Den norske Bank in Norway, and Credit Suisse in Switzerland. The press then promised a bright future for this system.

Nevertheless, things did not go as planned. Due to his stubborn and suspicious nature, David Chaum wanted to keep control over his company and refused partnerships with major financial players like ING and ABN AMRO, Visa, Netscape, and Microsoft. He left his position in 1997, and the same year the company moved its headquarters to California. During 1998, the partner banks announced they were abandoning eCash. DigiCash eventually went bankrupt in November 1998, ending this implementation of Chaumian electronic cash.

The Legacy of David Chaum's Model

The development of the eCash model, however, was not fruitless. It laid the groundwork for multiple initiatives. During the 1990s, other technical solutions for making payments on the Internet took advantage of the trend started by eCash: this was the case with CyberCash, First Virtual, or Open Market, which benefited from the disadvantages of credit card payments, which were impractical, costly, and insecure at the time. Micropayment systems also emerged, such as CyberCoin (managed by CyberCash), NetBill, and MilliCent. These systems never really took off, but they paved the way for the development of PayPal starting in 1999, a case that we will discuss in the following chapter. Other alternative centralized systems also appeared in parallel, such as e-gold and Liberty Reserve. These managed private digital currencies and benefited from the legal ambiguity that could exist in cyberspace. We will also talk about this in the next chapter.

Then, eCash inspired the cypherpunks who developed their own models such as b-money, bit gold, and RPOW. They added proof of work and other elements, which were later found in Bitcoin. We will study these concepts in Chapter 3.

Finally, David Chaum's model significantly influenced Satoshi Nakamoto when he developed his concept of currency. This is evidenced by the multiple references in the white paper (the title, the description of the problem in section 2, the name of the PDF sent to Wei Dai in August 2008), as well as his private and public interventions. In this sense, eCash is the main predecessor of Bitcoin, even if it is not the only one.

With Bitcoin, Satoshi Nakamoto created a robust and confidential digital currency, real electronic cash. In doing so, he realized the prediction of Milton Friedman, Nobel Prize in Economics and founder of the Chicago School, who said in an interview with the National Taxpayers Union Foundation in 1999:

"I think that the Internet is going to be one of the major forces for reducing the role of government. The one thing that's missing, but that will soon be developed, is a reliable e-cash, a method whereby on the internet you can transfer funds from A to B without A knowing B or B knowing A."

Private Digital Currencies

In the previous chapter, we explored the first form of electronic cash that emerged from the advent of the Internet and modern cryptography: David Chaum's eCash model. This model significantly influenced Satoshi Nakamoto and was a key milestone on the path that led to Bitcoin. However, the story of cryptocurrency's origins doesn't end with eCash; it also includes the experiments with private currencies operating on the Internet, developed from the late 1990s.

In this chapter, we will look at what was done in the realm of private currencies in the United States. We will first discuss the case of the Liberty Dollar. Then, we will examine centralized systems like e-gold and Liberty Reserve. Finally, we will talk about PayPal, whose approach is different, but nonetheless serves as an illuminating example of the model based on a trusted third party.

In all cases, these systems were eventually shut down by authorities or had to comply with financial regulations. This is why Satoshi Nakamoto, who had a good understanding of these systems, deeply understood the need for an alternative system not to rely on a central authority.

Monetary Freedom in the United States and the Liberty Dollar

The history of the United States was characterized by a great monetary plurality from its beginnings. From the 17th century to the mid-19th century, the English colony turned independent republic indeed allowed the free circulation of foreign currencies (the US dollar was not officially created until 1792), as well as the private minting of gold and silver coins. A relative banking freedom also prevailed between 1837 and 1863.

However, things changed with the Civil War, won by the Union, in a process of centralizing power. Thus, a law from Congress on June 8, 1864, prohibited the private minting of coins. This law, which has become section 486 of title 18 of the United States Code (18 U.S. Code § 486), stated: "Anyone, except as authorized by law, who manufactures, circulates, or attempts to circulate or pass, coins of gold, silver, or other metals, or metal alloys, intended to be used as current currency, whether they resemble coins of the United States or foreign countries, or are of original design, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned for no more than five years, or both."

To enforce these restrictions, a government agency was founded in 1865 by Abraham Lincoln: the Secret Service. The initial mission of the Secret Service was to combat counterfeiting and financial fraud in general. Indirectly, it served to strengthen the federal state's seigniorage by entrusting the monopoly on currency production to the United States Mint.

The situation became even more restricted afterward. The central bank, called the Federal Reserve of the United States, was created in 1913, following the banking panic of 1907. Then, the classic gold standard was abandoned in 1933 as part of F.D. Roosevelt's New Deal, with Executive Order 6102 which prohibited individuals and companies located in the United States from holding gold. The reference to gold in the monetary system was finally abandoned in 1971 when Richard Nixon announced the end of the dollar's convertibility into gold internationally. With the repeal of the gold possession ban and the development of the Internet starting in the 1970s, the idea of deploying private currencies re-emerged. This was the case with Bernard von NotHaus, who launched the Liberty Dollar in 1998, a currency based on gold and silver that could be found in the form of silver coins and representative notes. The system was managed by a non-profit organization called NORFED (acronym for National Organization for the Repeal of the Federal Reserve and Internal Revenue Code). Starting in 2003, the Liberty Dollar was also available in digital form, through an account system similar to e-gold (see the following section). The system experienced a certain level of success. Besides the circulating coins, NORFED's vaults contained about 8 million dollars in precious metals to ensure the currency's convertibility, including 6 million to back the digital unit.

Liberty Dollar (10 dollars) in silver from 2003 (source: Numista)

Liberty Dollar (10 dollars) in silver from 2003 (source: Numista)

In September 2006, the U.S. Mint issued a press release, written jointly with the Department of Justice, in which it concluded that the use of NORFED's coins violated section 486 of title 18 of the United States Code and constituted "a federal crime." Consequently, after an FBI raid on NORFED's premises in 2007, the violations were held against NotHaus and his associates, who were arrested in 2009 and tried in March 2011. In 2014, Bernard von NotHaus was sentenced on appeal to six months of house arrest and three years of probation.

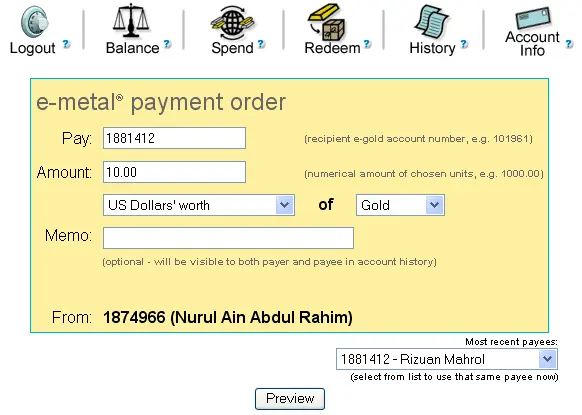

e-gold: Gold on the Web

An emblematic example of private electronic currency is the e-gold system. It was what is known as a "digital gold currency," meaning a currency electronically transferred and fully backed by an equivalent amount of gold stored securely. It was co-founded by Douglas Jackson and Barry Downey in 1996. Douglas Jackson was an American oncologist living in Florida, who was a follower of the Austrian economist Friedrich von Hayek and wanted to create a "better money" with e-gold. The principle was that each unit of e-gold could be converted into real gold. The gold reserves were managed by a company located in the United States called Gold & Silver Reserve Inc. (G&SR). The computer system was managed by a second company, e-gold Ltd., registered in Saint Kitts and Nevis in the Caribbean. Gold was not the only metal involved: users could also hold and exchange e-silver, e-platinum, and e-palladium, built on the same model.

The e-gold system took advantage of the nascent Web, and in particular the very recent Netscape browser. Each client could access their account from the website, rather than having to operate dedicated software. For the time, the platform was very high-performing, utilizing a real-time gross settlement system inspired by interbank transfer. Here is what sending e-gold looked like in 2005 (image from a tutorial of the time):

The e-gold system met with great success: at its peak in 2006, it guaranteed 3.6 tons of gold, worth more than 80 million dollars, processed 75,000 transactions per day, for an annualized volume of 3 billion dollars, and managed more than 2.7 million accounts. This success was abruptly halted following the intervention of the State. After an investigation conducted by the Secret Service, Douglas Jackson, his two companies, and his associates were indicted on April 27, 2007, by the Department of Justice for facilitating money laundering and operating a money transfer business without a license. In November 2008, Douglas Jackson was found guilty and was sentenced to 3 years of probation, including 6 months of house arrest under electronic surveillance. After an unsuccessful attempt to obtain a license, e-gold was forced to permanently shut down in November 2009.

Other systems were created following the same model. We can mention GoldMoney, founded by James Turk and his son in February 2001, which has today adapted to financial regulations. e-Bullion, the system founded by James Fayed in July 2001, closed its doors in 2008. Finally, one of the last digital gold currencies was Pecunix, which was founded in Panama by Simon Davis in 2002 and ceased operations in 2015, as part of an exit scam.

Liberty Reserve, the Alternative to the Federal Reserve

Another example of a centralized private currency system is Liberty Reserve, which allowed its users to hold and transfer electronic currencies pegged to the US dollar, the euro, or gold. This system was created by Arthur Budovsky, an American of Ukrainian origin, and Vladimir Kats, a Russian immigrant from Saint Petersburg. In 2006, Arthur Budovsky expatriated to Costa Rica, then considered a tax haven, where he registered his company, Liberty Reserve S.A.

Liberty Reserve logo in 2009 (source: Wikimedia)

Liberty Reserve logo in 2009 (source: Wikimedia)

The system was quite similar to e-gold, except that the funds (primarily in dollars) were held in offshore bank accounts, rather than in private vaults. Liberty Reserve greatly benefited from the shutdown of e-gold in April 2007 following the indictment of Douglas Jackson and his associates. In May 2013, according to the U.S. Department of Justice, the platform had over one million users worldwide, including more than 200,000 in the United States, and processed 12 million financial transactions annually, for a combined volume of more than $1.4 billion. The use was primarily for criminal activities, but was not limited to these: Liberty Reserve was also used by Forex traders or for overseas transfers.

However, the system eventually met the same fate as e-gold. In 2009, the Costa Rican Superintendencia General de Entidades Financieras took an interest in Liberty Reserve, asking it to obtain a license (which the company failed to do). Then, in November 2011, the U.S. FinCEN issued a notice stating that the system was "used by criminals to conduct anonymous transactions to move money globally." Finally, Liberty Reserve was shut down at the end of an international operation: on May 24, 2013, Arthur Budovsky and his main associates were indicted and arrested in different jurisdictions (Spain, United States, Costa Rica) and the main site was seized by the Department of Justice. In 2016, after being extradited to the United States, Arthur Budovsky was sentenced to 20 years in prison for money laundering.

This example thus shows that jurisdictional arbitrage is not enough to protect currency from state intervention.

PayPal and Peter Thiel's Vision

Finally, we must discuss the case of PayPal. Although its creators did not intend to make it a currency independent of the existing system, they nonetheless envisioned that this product would have an effect on society, in line with the disruptive ideology of Silicon Valley. The PayPal product was developed by Confinity Inc., co-founded in December 1998 in San Francisco by Max Levchin and Peter Thiel, who had met a few months earlier at Stanford University. The company, initially called FieldLink, aimed to develop secure payment systems on PalmPilot handheld computers.

PayPal was created in October 1999 by an engineer of the company. It allowed for easy and fee-free payments between email addresses and was intended for the transfer of simple payments between individuals ("pay pal"). Its business model was based on earning interest from the funds of clients held in banks, which covered operating costs and rewarded shareholders. Thus, it was a service built on top of the banking system, similar to Liberty Reserve.

As the Internet bubble was at its peak, the product experienced rapid growth from the first months, notably thanks to its referral system. This success caught the attention of competitors, who had much more capital, copied the idea, and launched their own version of the service, to the detriment of Confinity. This is why the company had to merge with one of them, the online bank X.com owned by Elon Musk, to become PayPal Inc. in March 2000.

The original vision of PayPal was revolutionary, in line with Peter Thiel's libertarian vision. Here is what he said in the fall of 1999, as reported by Eric Jackson in 2012 in The PayPal Wars:

"Of course, what we're calling 'convenient' for American users will be revolutionary for the developing world. Many of these countries' governments play fast and loose with their currencies. They use inflation and sometimes wholesale currency devaluations, like we saw in Russia and several Southeast Asian countries last year, to take wealth away from their citizens. Most of the ordinary people there never have an opportunity to open an offshore account or to get their hands on more than a few bills of a stable currency like U.S. dollars. Eventually, PayPal will be able to change this. In the future, when we make our service available outside the U.S. and as Internet penetration continues to expand to all economic tiers of people, PayPal will give citizens worldwide more direct control over their currencies than they ever had before. It will be nearly impossible for corrupt governments to steal wealth from their people through their old means because if they try, the people will switch to dollars, Pounds, or Yen, in effect dumping the worthless local currency for something more secure."

Peter Thiel on October 20, 1999, during his speech in Oakland, California for

the Independent Institute (source: Youtube)

Peter Thiel on October 20, 1999, during his speech in Oakland, California for

the Independent Institute (source: Youtube)

However, things did not evolve in the desired direction, and PayPal had to comply with all sorts of financial regulations, to the point that the service is now famous for its payment censorship and account freezes all around the world. It was naive to believe that such a system could challenge the established power.

Centralized Alternatives and Bitcoin

Thus, we observe that attempts to create centralized services as alternatives to the existing system have all eventually been halted, in one way or another. The disadvantage of these models is that they rely on a trusted third party, which can go bankrupt, abscond with the funds, or be controlled by the authorities. In the latter case, the service in question faces a dilemma: adapt by complying with financial regulations, as GoldMoney and PayPal did, or perish by refusing to comply, a fate suffered by e-gold, Liberty Reserve, and the Liberty Dollar. The closure of these systems was contemporary with the creation and early days of Bitcoin. Consequently, Satoshi Nakamoto and the early users of Bitcoin were well aware of them. As for Satoshi, he was aware of the model used by e-gold and mentioned Pecunix and Liberty Reserve several times in his public and private interventions.

It is because of this fragility of centralized systems that proponents of freedom – including notably the cypherpunks – sought to create a decentralized currency. It was necessary to find a way to avoid placing the entire system's infrastructure on a single point. That's why several "trust-minimizing" models emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s, before the discovery of Bitcoin. The next chapter will be dedicated to these models.

Decentralized Models Before Nakamoto

Bitcoin represents a decentralized model of digital currency. In doing so, it avoids the need for a trusted third party, which would constitute a single point of failure in the system. As shown by the examples of eCash, digital gold currencies, and Liberty Reserve, the centralization of a system intending to be an alternative to the existing system inevitably leads to its closure, in one way or another. Bitcoin, however, was not the first concept of decentralized currency to have been proposed. Since the late 1990s, such models had been described by the cypherpunks, who were obsessed with freedom and privacy of individuals on the Internet, and who believed (like David Chaum) that monitored systems led to a dystopian future. They called for "writing code" and considered "electronic money" as an essential element to their ideal. (original: "Cypherpunks write code. (...) We are defending our privacy with cryptography, with anonymous mail forwarding systems, with digital signatures, and with electronic money.")

In this chapter, we will study the emergence of various foundational technical elements that were later used in Bitcoin: distributed consensus, timestamping, and proof of work. Then, we will talk about b-money, bit gold, and RPOW, respectively designed by cypherpunks Wei Dai, Nick Szabo, and Hal Finney. Finally, we will discuss the case of Ripple, whose model is slightly different, but which has its place in the history of Bitcoin's creation.

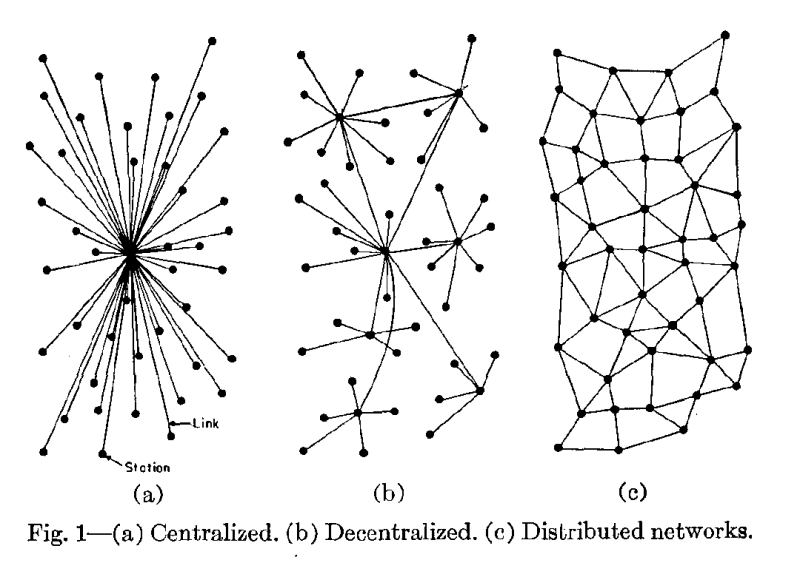

Distributed Consensus

With the emergence of computers in the 1950s, the possibility of connecting them to each other appeared. This is how the first computer networks were formed, leading to the development of the Internet, the "network of networks," in the 1970s. The question of the infrastructure of these networks inevitably arose. That's why the Polish-American computer scientist Paul Baran, in his foundational 1964 article (describing packet switching), listed three types of networks: the centralized network, relying on a single node; the distributed network, where each point is a node; the decentralized (non-distributed) network, relying on a distributed network of multiple nodes.

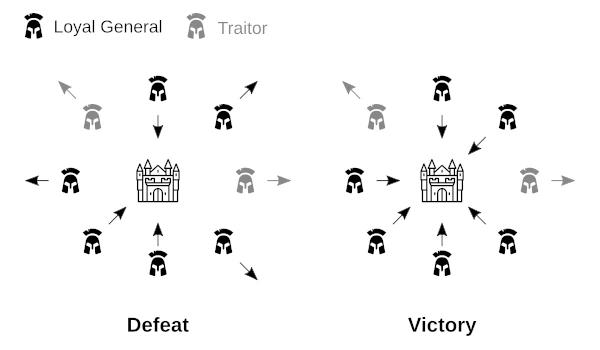

Two pure models can be derived from these considerations: the client-server model, where a central server responds to the requests of clients, and the peer-to-peer model, where each node has the same role in the system. This latter model was particularly useful for file sharing in the 2000s, with the creation of BitTorrent and other similar protocols. The Tor network is decentralized, not purely peer-to-peer. A problem encountered in distributed architectures is the issue of distributed consensus, commonly referred to as the Byzantine Generals Problem, which was formalized by Leslie Lamport, Robert Shostak, and Marshall Pease in a paper published in 1982. This problem addresses the challenge of transmission reliability and the integrity of participants in peer-to-peer systems, and it applies in cases where the components of a computer system need to agree.

The problem is stated in the form of a metaphor involving generals of the Byzantine Empire's army, who are besieging an enemy city with their troops intending to attack and can only communicate via messengers. The goal is to find a strategy (i.e., an algorithm) that can manage the presence of traitors and ensure that all loyal generals agree on a battle plan so that the attack is successful. Here is an illustration (source: L'Élégance de Bitcoin):

Solving this problem is important for distributed systems that would manage a unit of account. Such systems indeed require that participants agree on the ownership of account units, that is, on who owns what.

Before Bitcoin, the problem was solved absolutely by so-called "classical" algorithms that required the nodes to be known in advance and that two of them be honest. The most well-known among these is probably the consensus algorithm PBFT (acronym for Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance), which was developed by Miguel Castro and Barbara Liskov in 1999 and allowed a given number of participants to agree by managing thousands of requests per second with a latency of less than one millisecond.

With the Bitcoin consensus algorithm, Satoshi Nakamoto solved it in a probabilistic manner, allowing for the removal of certain constraints by sacrificing the strict finality of transactions. On November 13, 2008, he wrote that "the proof-of-work chain is a solution to the Byzantine Generals' Problem."

Document Timestamping

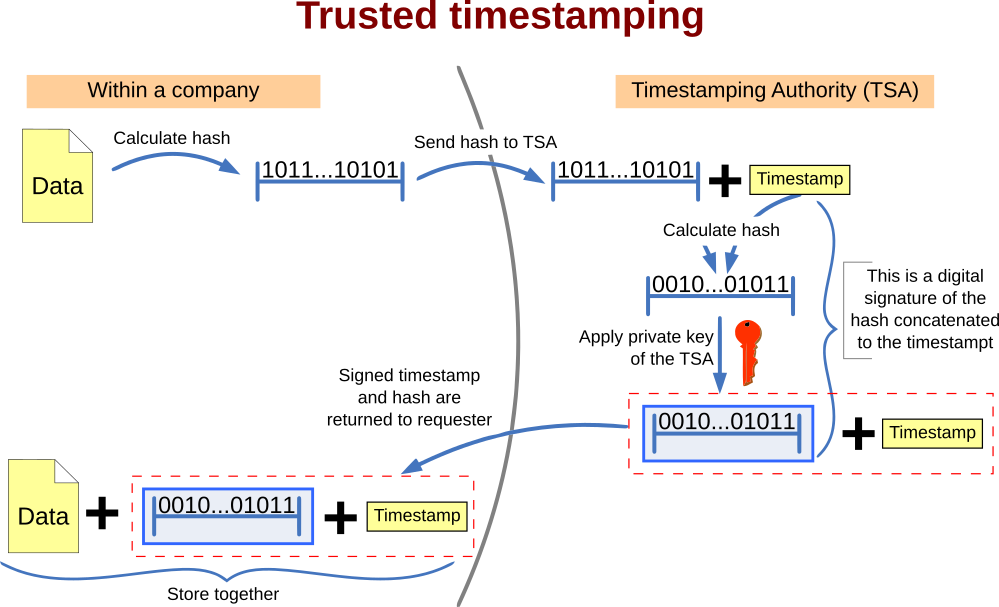

Timestamping is a technique that involves associating a date and time with information such as an event or a document. From a legal perspective, this can, for example, ensure the existence of a contract before a given date. In the real world, there are numerous ways to timestamp something, such as sending a document in a sealed envelope or recording a timeline in a notebook. However, timestamping is particularly useful in the digital world, where files (text, image, audio, or video) are easily modifiable. Timestamping can be performed by centralized services, which are responsible for saving received documents (or their fingerprints) and associating them with the date and time of receipt. This is referred to as trusted timestamping.

In 1991, a confidential and secure timestamping technique was proposed by Stuart Haber and Scott Stornetta, two researchers working for Bell Communications Research Inc. (commonly called "Bellcore"), an R&D consortium located in New Jersey. In their paper, titled "How to time-stamp a digital document", they described how a certified timestamping service could use a one-way function (such as the MD4 hash function) and a signature algorithm to increase the confidentiality of client documents and the reliability of the certification. In particular, the idea was to chain the information by involving the previous timestamp in the application of the one-way function.

Example of certified timestamping (source: Wikimedia)

Example of certified timestamping (source: Wikimedia)

Haber and Stornetta implemented their idea by publishing cryptographic fingerprints (resulting from hashing the useful data) in the classified ads of the New York Times starting in 1992. They then founded their own company in 1994, Surety Technologies, with the aim of fully dedicating themselves to this activity. They are thus known for creating the first timestamp chain, with the previous fingerprint being taken into account in the calculation of the new fingerprint to be published in the newspaper, which foreshadowed the Bitcoin blockchain. Three papers by Haber and Stornetta were cited by Satoshi Nakamoto in the Bitcoin white paper: the previously mentioned 1991 paper, a paper from 1993 that improved upon the protocols proposed in the earlier one, notably through the use of Merkle trees, and a paper from 1997 that presented a way to universally name files using one-way functions. Also cited was a paper describing a new timestamping system written in 1999 by Henri Massias, Xavier Serret-Avila, and Jean-Jacques Quisquater, three men working for the cryptography research group at the Catholic University of Louvain, in Belgium.

Proof of Work and Hashcash

Proof of work is a process that allows a computer device to demonstrate in an objective and quantifiable manner that it has expended energy, in order to be selected for access to a service or privilege. It is essentially a mechanism to resist Sybil attacks, which makes it difficult for an attacker to excessively multiply identities to disrupt or take control of any reputation system.

The concept of proof of work was first described in 1992 by computer scientists Cynthia Dwork and Moni Naor, who were then working at the IBM Almaden research center, located south of San Jose in California. In a research paper titled "Pricing via Processing or Combatting Junk Mail", they presented a method to combat spam in email inboxes. The model consisted of forcing users to solve a cryptographic puzzle for each email sent, in order to limit the ability to send mass emails while allowing occasional senders not to be hindered. However, they never went as far as to implement their idea. With the popularization of the Internet in the 1990s, the problem of unwanted email became increasingly pressing, including on the mailing list of the cypherpunks. This is why the concept by Dwork and Naor was implemented by the young British cypherpunk Adam Back in 1997 with Hashcash, an algorithm producing simple proofs of work using a hash function. More specifically, it involves finding a partial collision of the considered hash function, that is, obtaining two messages that have a footprint starting with the same data bits (note: from version 1.0 released in 2002, it involves discovering a partial collision for the zero print, namely finding a pre-image whose footprint starts with a determined number of binary zeros). Since the hash function is one-way, such an achievement can only be realized by testing the different possibilities one by one, which requires an energy expenditure.

Adam Back in 2001 (source: archive of Adam Back's personal page)

Adam Back in 2001 (source: archive of Adam Back's personal page)

But the cypherpunks did not limit themselves to considering proof of work as a simple means of limiting spam; they also wanted to use it as a way to guarantee the cost of producing a digital currency. Thus, in 1997, Adam Back envisaged this idea himself, but he was aware that the proofs of work thus obtained could not be transferred in a fully distributed manner (because of the double-spending problem) and that it was therefore necessary to go through a centralized system like eCash. Similarly, in 1996, cryptographers Ronald Rivest and Adi Shamir described MicroMint, a centralized micropayment system whose coins were supposed to be impossible to counterfeit thanks to the production of proofs of work.

A good arrangement had to be found that would allow such a model to function robustly and sustainably. This is what the cypherpunks Wei Dai, Nick Szabo, and Hal Finney tried to develop with their respective protocols – b-money, bit gold, and RPOW – which we will examine next. And this is what Satoshi Nakamoto ended up doing by including Hashcash in his design of Bitcoin.

b-money: the decentralized stablecoin

The first protocol to emerge from the cypherpunk movement was b-money, a decentralized digital currency model conceptualized by Wei Dai in 1998. He was a young Chinese-American cryptographer living in Seattle and working for Microsoft, who got involved in the mailing list starting in 1994. He notably made a name for himself by creating the open-source Crypto++ library, which was later used in Bitcoin software.

Wei Dai published the descriptive text of b-money on November 26, 1998, on his personal page and shared the link to the cypherpunk mailing list the same day. In his email, he described b-money as "a new protocol for monetary exchange and contract enforcement for pseudonyms."

In his concept, the system was based on an untraceable peer-to-peer network. Each participant was identified by a "digital pseudonym," that is, a public key, and each transaction message was signed by the sender and encrypted for the recipient. Each participant maintained a database that listed the amounts of b-money units held by each pseudonym.

Currency creation was open to all participants and was done through proof of work by broadcasting the solution to a known and previously unsolved computational problem. The number of units created depended on the cost of this effort expressed relative to a standard basket of goods (including, for example, precious metals), in order to maintain the unit's value around a "stable" equilibrium point. The system also offered the possibility to create and execute contracts directly on the network, thanks to a rudimentary escrow process.

Although quite ingenious, the concept of b-money presented by Wei Dai was not entirely functional. It thus had major flaws such as vulnerability to Sybil attacks on the network (anyone could theoretically add new nodes to the network), network centralization in the case where servers would be pre-selected, and the issue related to the stabilization of the unit of account (who decrees the observable prices on the market?). After its publication on the list, b-money caught the attention of the cypherpunks, and in particular that of Adam Back. However, Wei Dai never implemented his model, not only because it was dysfunctional, but also due to the disillusionment of the cryptographer towards crypto-anarchy. Nevertheless, b-money ended up being cited in the Bitcoin white paper, making it one of its precursors.

bit gold: digital gold before Bitcoin

The second model to have emerged from the ideas of the cypherpunks was the idea of bit gold imagined by Nick Szabo in 1998. He was an American computer scientist of Hungarian origin, who had notably worked as a consultant for DigiCash for six months. A cypherpunk, he is known for having formalized the notion of smart contract in 1995.

In 1994, Nick Szabo had created a private mailing list called libtech-l, which aimed, as its name suggests, to host discussions on liberatory techniques, allowing the protection of individual freedoms against the assaults of authorities. Cypherpunks like Wei Dai and Hal Finney had access, as well as economists Larry White and George Selgin, proponents of Hayekian currency competition and free banking.

Nick Szabo in 1997 (source: Adrien Chen)

Nick Szabo in 1997 (source: Adrien Chen)

It was on the libtech-l list that Nick Szabo initially described his concept, before hosting a draft of a white paper in 1999 on his personal website. He then presented bit gold in 2005, in an article published on his blog, Unenumerated.

The protocol was supposed to manage the creation and exchanges of a virtual resource called bit gold. Unlike e-gold, which was guaranteed by physical gold, or b-money theoretically indexed to a basket of goods, bit gold was not to be backed by any other asset, but possess an unforgeable scarcity intrinsic to it, thus constituting an entirely digital gold. The central element of the protocol was that money creation was done through proof of work: bits of bit gold were created using the computing power of computers, and each solution was calculated from another, leading to the formation of a chain of work proofs. The date and time of production of these work proofs were certified using multiple timestamp servers. The system relied on a public registry of property titles, referencing the possessions and exchanges of users, who were identified by their public keys and authorized transactions using their private keys. The registry was verified and maintained by a network of servers called the "property club," coordinated by a classic consensus algorithm called Byzantine Quorum System.

The resemblance of bit gold to Bitcoin is striking. The three constituent elements of the system (the production of work proofs, their timestamping, and the management of the property registry), which were separate in bit gold, are found in Bitcoin as a single concept: the blockchain. This is why many have seen it as a draft of Bitcoin and speculated that Nick Szabo could be Satoshi.

However, the visions of the two men diverged. In bit gold, the way digital gold pieces were produced meant they were not fungible, meaning they could not be mixed with each other: they had to be evaluated on an external market to the system to be used as a basis for a real homogeneous unit of account. The bit gold model was thus conceived as a settlement system for managing a rare reserve currency, on top of which a free banking economy would be built, if possible using the Chaumian model. Thus, in April 2008, in a comment on his blog, Nick Szabo was still asking for help to implement his concept. However, this implementation never took place.

RPOW: Reusable Proofs of Work

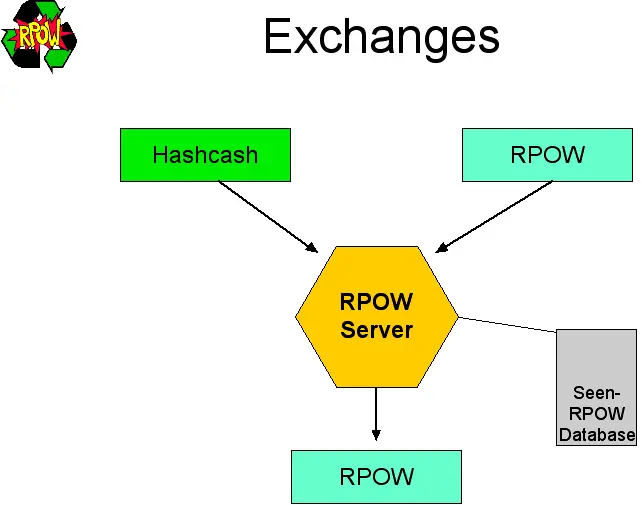

The third system to emerge from the minds of the cypherpunks is the RPOW system, an abbreviation for Reusable Proofs of Work, developed by Hal Finney in 2004. Hal Finney was an American computer scientist and cryptographer who lived in the Los Angeles area. A cypherpunk from the early days, he was passionate about the ideas of David Chaum and his famous eCash model. He had been working since 1996 on the development of the PGP encryption software with Phil Zimmermann.

To design his RPOW system, Hal Finney took the ideas behind eCash and bit gold. The uniqueness of his system was that it was based on a transparent server that allowed the transfer of work proofs produced by Hashcash. This server used the IBM 4758 Secure Cryptographic Coprocessor, a high-security tamper-resistant element, which allowed, through an authentication process designed by IBM, to verify which programs were running on the machine. An external user could thus ensure at any time that the RPOW server was running the correct program, whose code was also publicly available.

The reusable proof of work tokens were managed by the server, which was responsible for signing them using RSA encryption. They were created by producing a proof of work via Hashcash, or from a previous RPOW token. During a payment, the sender gave their RPOW tokens to the recipient who would promptly communicate with the server to receive one or more new tokens, whose total value was equal to the input value. The operation of RPOWs was thus similar to that of digital tickets in eCash.

Here is an illustration designed by Hal Finney himself:

Hal Finney not only designed the model but also personally implemented it. On August 15, 2004, he announced the launch of the RPOW system on the cypherpunks mailing list, in addition to documenting its operation on the dedicated website (rpow.net). He then presented it at the CodeCon 2005 conference held in San Francisco, where he discussed the potential uses for proof-of-work tokens, namely: value transfer, spam regulation, commerce in video games, online gambling like poker, and anti-leeching on file-sharing protocols like BitTorrent. However, RPOW had intrinsic flaws that may explain why it did not achieve the expected success:

- Its security model was rather weak, as it relied on a centralized server;

- Its monetary policy (based on hashing) was not particularly attractive due to the exponential increase in computing performance.

Thus, the actual use of RPOW was anecdotal, but Hal Finney deserves credit for "paving the way" (original: "carried this torch") to Bitcoin by setting up an experimental proof of concept, four years before the arrival of Satoshi Nakamoto.

Ripple: The Decentralization of Credit

Another lesser-known predecessor model of Bitcoin, but nonetheless significant here, is the distributed credit protocol Ripple, designed by Canadian developer Ryan Fugger in 2004. The young Canadian was inspired by the concept of the local exchange trading system (LETS), something he had experienced in Vancouver before designing his protocol. He published the Ripple white paper on April 14, 2004, and then implemented it through a proof of concept called RipplePay, which operated on a central server and allowed users to connect with just an email address.

Ryan Fugger circa 2010 (source: Crunchbase)

Ryan Fugger circa 2010 (source: Crunchbase)

The concept of Ripple was based on the idea that money was essentially made

up of IOUs, that is, credit. It was about establishing a peer-to-peer

network whose links would be credit relationships between people. Payments

were then made by routing a series of loans, with all participants acting as

bankers lending money to each other. Alice could pay David 10 by lending10 to Bob, and asking Bob to do the same to Carole, then Carole to do

the same to David: David's account was then credited with $10 from Alice's

creation of money. The system worked somewhat by ripples, which explains the

name of the project.

Here is an introductory video of Ripple made in 2011:

Despite the enthusiasm of its community and a few thousand users, Ripple had major flaws that prevented it from being successful. In particular, it suffered from the "problem of decentralized commitment": during a payment, participants could not commit in a secure way to ensure the loan chain, a problem that would be solved later by Lightning. (original: "the problem of the decentralized commit")

Seeing that his project was going nowhere, Ryan Fugger handed over the reins of Ripple to the leaders of the company OpenCoin Inc., Chris Larsen and Jed McCaleb, in November 2012. The company was renamed Ripple Labs in 2013. They made it into a protocol significantly different from the initial concept, based on a consensus algorithm and on a native unit of account, the XRP. Ryan Fugger eventually changed the name of his proof of concept to Rumplepay in 2020 to avoid confusion.

Ripple was, so to speak, contemporary with Bitcoin, and it turns out that many people interested in the latter were also interested in the former. Indeed, Ripple constituted an innovative model, based on a distributed architecture, a characteristic shared with Bitcoin. On this subject, Satoshi Nakamoto wrote that "Ripple is unique in that it spreads trust rather than concentrating it."

Bitcoin, the culmination of a quest

Thus, by the end of the 2000s, all the constituent elements of Bitcoin were known, and several attempts to combine them had been made. However, the proposed assemblies were not convincing. The cypherpunks, in particular, gradually lost interest in this issue, believing that the design of a truly decentralized digital currency was impossible. Satoshi Nakamoto proved them wrong.

Bitcoin indeed constitutes an ingenious assembly of all these concepts. It is based on digital signature, stemming from the asymmetric cryptography proposed by Diffie and Hellmann in 1976. It is "electronic cash" as intended by David Chaum's eCash model implemented in the 90s. With its innovative consensus algorithm, it robustly solves the Byzantine Generals' Problem, stated by Lamport, Shostak, and Pease in 1982. With the management of its blockchain on a peer-to-peer network, it is a form of "distributed timestamp server," revisiting the concept by Haber and Stornetta from 1991. For the selection of transaction blocks and for the production of units, it makes use of proof of work, using a process similar to Hashcash, proposed by Adam Back in 1997. Finally, in its design, it recalls the projects of b-money, bit gold, RPOW, and Ripple, to which Satoshi Nakamoto paid tribute, in one way or another.

Bitcoin thus forms the culmination of a quest for cybercurrency, a currency existing entirely on the Internet and not at the mercy of states. In the rest of this course, we will recount how it came to life and what were the significant events of its early years. This story is unique and will surely interest you if you have come this far. Be ready!

The Slow Emergence of Bitcoin

The Birth of Bitcoin

After learning where Bitcoin came from, we will now focus on its history itself. This has been the subject of numerous articles, podcasts, and videos over the years, so much so that it has almost become a sort of founding myth. As we have seen, Bitcoin is inseparable from the context in which it was created; the same is true for the events that took place during its early years, which have shaped what it is today, with its qualities and flaws. Bitcoin was created by Satoshi Nakamoto, an unknown individual claiming to be Japanese, who took the time to thoughtfully design it before unveiling it to the public. Subsequently, they did everything to ensure that Bitcoin was launched under the best conditions, that it was well presented in discussions, and that it was used by an increasing number of people. Ultimately, the creator's effort lay as much in the economic initiation of the system as in its initial design, if not more.

This chapter deals with the birth of Bitcoin, which took place between the fall of 2008 and the winter of 2009. This period was marked by two major events: the publication of the white paper, the foundational document that explains the technical workings of the system, on October 31, 2008; and the launch of the prototype network on January 9, 2009, just over two months later. We will thus focus on Satoshi Nakamoto's actions during this period and the few interactions he had with Bitcoin's early adopters and first detractors.

The Discovery

According to his own testimony, Satoshi Nakamoto began working on Bitcoin during the spring of 2007. After conducting various research on the topic of digital currencies, he eventually found a way to solve the double-spending problem without the need for a trusted third party. For over a year, he kept his model a secret, wanting to refine it to ensure its robustness. As he wrote later:

"At some point, I became convinced there was a way to do this without any trust required at all and couldn't resist to keep thinking about it. Much more of the work was designing than coding."

To ensure it functioned correctly, Satoshi programmed a prototype before drafting the white paper. This approach is the opposite of what is usually done within the academic community, where concepts are formally presented in scientific papers before being implemented. The creator of Bitcoin stated:

"I actually did this kind of backwards. I had to write all the code before I could convince myself that I could solve every problem, then I wrote the paper."

Preparation

It was in August 2008 that Satoshi decided to prepare for the launch of Bitcoin. On the 18th, he reserved the domain name Bitcoin.org through the anonymous service AnonymousSpeech (as well as Netcoin.org, probably having not finalized the choice of name for his concept). The domain name would host the main Bitcoin site. However, Satoshi was unable to reserve the domain name Bitcoin.com, which was then held by a speculator and would be used between 2009 and 2011 by a company called BitCoin Ltd., specializing in micropayments.

On August 20th, the creator of Bitcoin contacted Adam Back by sending him an email asking for advice on how to cite his paper on Hashcash in the white paper. It's hard not to see this as a pretext to ensure that the inventor of Hashcash became aware of his new system.

Adam Back in 2012 (source: Adam Back's personal page)

Adam Back in 2012 (source: Adam Back's personal page)

The email contained a link to a draft of the white paper. The PDF file name

was ecash.pdf and its title was "Electronic Cash Without a Trusted

Third Party". The abstract is the same as the one from the first version that

would be published in October, with one word difference. Unfortunately, we do

not have the full document. The day after reading the summary sent by Satoshi

(but not the paper), Adam Back redirects him to Wei Dai's b-money proposal, which

seems to have similarities with his concept. Satoshi responds by thanking him

for the pointer and specifying that "my ideas start from exactly that point."

Adam Back also mentions the existence of MicroMint, but Satoshi does not respond.

The day after that, on August 22, Satoshi sends an email to Wei Dai saying he "is getting ready to release a paper that expands on your ideas into a complete working system" and asks him for the publication year of his page on b-money to reference it in the white paper. As in his exchange with Adam Back, he shares the draft of the white paper with Wei Dai.

Despite these interactions, Adam Back and Wei Dai did not immediately take an interest in Satoshi's concept. It would only be years later that they would return to Bitcoin: Wei Dai in 2010-2011 and Adam Back in 2013.

For his part, Satoshi finishes preparing to make his invention public. On October 3, he completes the first version of the Bitcoin white paper, now with its name chosen. On October 5, he registers on the SourceForge project management platform, where the open-source software's source code would be hosted and maintained until 2011.

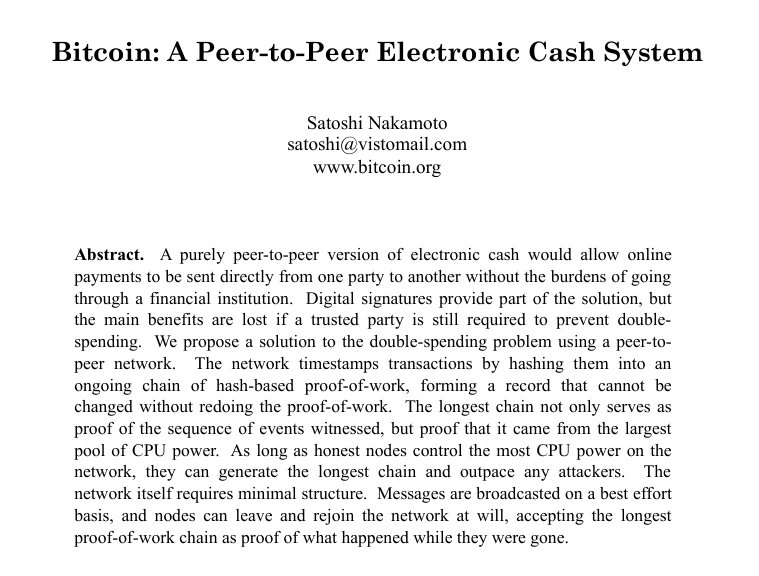

The publication of the white paper

On October 31, 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto publishes the first version of the white paper on an email mailing list dedicated to cryptography, simply called the "Cryptography mailing list." This list has been managed by developer Perry Metzger since 1996, its creation, and has been hosted on his personal site, Metdowd.com, since 2003. It is the successor to the cypherpunks list, with the difference that it is subject to strict moderation. In 2008, several former cypherpunks still participated, such as John Gilmore, Hal Finney, and Len Sassaman.

In his first email addressed to the list, Satoshi writes simply:

"I've been working on a new electronic cash system that's fully peer-to-peer, with no trusted third party."

It also lists the main properties of his model:

- "Double-spending is prevented with a peer-to-peer network."

- "No mint or other trusted parties."

- "Participants can be anonymous."

- "New units are made from a Hashcash style proof-of-work."

- "The proof-of-work used for generating new units also allows the network to prevent double-spending."

In his email, he includes a link to the white paper, already hosted on Bitcoin.org, which is a short 9-page document, presented as a scientific article, describing the technical workings of Bitcoin. This document focuses on the problem of online payments.

Following this announcement, Satoshi receives a few responses, but most of them are skeptical. He is notably criticized for three things:

First, the cypherpunk James A. Donald challenges the scalability of the system by saying that "it does not seem to scale to the required size." Satoshi replies that "the bandwidth might not be as prohibitive as you think."

The second negative comment comes from John R. Levine, author of the book Internet for Dummies and a consultant specializing in email infrastructure, spam filtering, and software patents. He criticizes Bitcoin's security by mentioning the computational power held by "zombie machine farms" composed of computers controlled by hackers. He specifically points out that, on the Internet, "the good guys have significantly less computational power than the bad guys." Satoshi responds brilliantly: "The requirement is that the good guys collectively have more computational power than any single attacker."

Finally, an individual named Ray Dillinger (using the pseudonym bear) wonders about the value of the unit of account, lamenting the fact that "computational proofs of work have no intrinsic value" and criticizing their inflationary nature due to the technical evolution of computer hardware. Satoshi replies that "the increase in hardware speed is accounted for" by the periodic adjustment of the production difficulty. Even though skepticism is the predominant attitude on the list, it is not shared by everyone subscribed to the mailing list. In particular, one person stands out from the others with their enthusiasm: Hal Finney, who has an optimistic view of the future and who never gave up on the idea of electronic cash, despite the failures of the 90s. He stated on this matter a few years later that "cryptographic graybeards [...] tend to become cynical" but that he "was more idealistic" having "always loved cryptography, its mystery, and its paradox." (original: "I've noticed that cryptographic graybeards (I was in my mid 50's) tend to get cynical. I was more idealistic; I have always loved crypto, the mystery and the paradox of it.") Thus, on November 7, he wrote in an email to the list that "Bitcoin seems to be a very promising idea" and compares Satoshi's model to Nick Szabo's bit gold. (original: "Bitcoin seems to be a very promising idea.")

Hal Finney in 2007

Hal Finney in 2007

Monetary Policy and Software Code

Bitcoin uses a distributed consensus algorithm that allows all network nodes to agree on the contents of a ledger, which Hal Finney refers to in his first email as the "block chain," in two words. The correct blockchain chosen is the one that has the most blocks, and conflicts over competing blocks are resolved according to this simple principle. The mechanism would be refined later to take into account the amount of work accumulated rather than the number of blocks.

This consensus mechanism allows for the imposition of all sorts of rules and incentives (to use the last phrase of the white paper) within the system. Since Bitcoin constitutes a distributed timestamping service, it is also possible to have these rules interact with the passage of time. Hence the difficulty adjustment algorithm that comes into play to regulate the production of new blocks and the bitcoins associated with them: if the number of blocks produced over a given period is too high, then the difficulty of production increases; in the opposite case, it decreases. Bitcoin thus differs from RPOW, where the work proofs themselves formed the units of account. Thanks to this difficulty adjustment, Bitcoin can therefore have a monetary policy, meaning that the amount of new units issued by the protocol can be predetermined. Initially, it is planned for the monetary issuance to be constant, in order to encourage producing nodes to contribute their computing power to the network, and there are no transaction fees. As Satoshi Nakamoto writes in the "Incentive" section of the white paper:

"The steady addition of a constant of amount of new coins is analogous to gold miners expending resources to add gold to circulation."

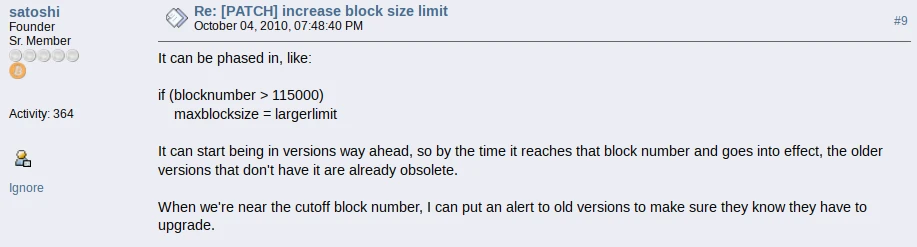

This property, confirmed by Satoshi on the mailing list and in his private correspondence, does not escape James A. Donald. On November 9, he criticizes the "work of tracking who owns what" (i.e., mining) for being "paid by seigniorage" and for "requiring inflation," even though he notes that "predictable inflation is less objectionable than inflation that gets jiggered around from time to time to transfer wealth from one voting block to another." (original: "in the proposed system the work of tracking who owns what coins is paid for by seigniorage, which requires inflation. This is not an intolerable flaw - predictable inflation is less objectionable than inflation that gets jiggered around from time to time to transfer wealth from one voting block to another.") Furthermore, he notes that a mining node which "ignores all the spends it does not care about" suffers "no adverse consequences," thereby highlighting the problem of censorship. (original: "If one node is ignoring all spends that it does not care about, it suffers no adverse consequences.")

These remarks probably made Satoshi realize that he could implement a transaction fee mechanism that solves both problems, by replacing the creation of new units and encouraging miners to "include all the paying transactions they receive." (original: "nodes would have an incentive to include all the paying transactions they receive.")

At the same time, the questions from his interlocutors prompted him to share the source code of his model. On November 16, Satoshi transmitted the code to Hal Finney, James A. Donald, and Ray Dillinger. On the 17th, in a response to James A. Donald on the mailing list, he wrote that he had sent him "the main files," which were "available by request at the moment" and that their "full release" would happen "soon." (original: "I sent you the main files. (available by request at the moment, full release soon)") In this portion of the code, which was made public in 2013 by Ray Dillinger, one can see that all the foundational elements of Bitcoin are present: the blockchain (then still called "timechain"), proof of work, the coin representation model (UTXO), transaction programmability, transaction fees, and halving.

However, some parameters differ, indicating that they were chosen

spontaneously or, as Satoshi wrote, by "educated guess." (original: "educated guess") The block

time, that is, the targeted period between each block, is 15 minutes instead

of 10. The difficulty adjustment period is 2,880 blocks (equivalent to 30

days for a block time of 15 minutes) instead of 2,016 blocks (which

corresponds to 14 days for a block time of 10 minutes). The halving

mechanism, present in the GetBlockValue function, dictates that

the halving should occur every 100,000 blocks, roughly every 2 years and 311

days:

int64 GetBlockValue(int64 nFees)

{

int64 nSubsidy = 10000 * CENT;

for (int i = 100000; i <= nBestHeight; i += 100000)

nSubsidy /= 2;

return nSubsidy + nFees;

}

There are 100 bitcoins created during the first 100,000 block period, 50 during the second period, etc., so that the total quantity of bitcoins converges towards 20 million. Each bitcoin (COIN) is divisible into 100 cents (CENT), which are themselves divisible into 10,000 base units, meaning a bitcoin can be divided into 1 million smaller units, and not 100 million as in version 0.1 that was released in January.