name: Hyperinflation Studies goal: Understanding the emergence of hyperinflations in a Fiat world and their consequences objectives:

- Study hyperinflation cycles

- Understand the real impacts of hyperinflations on our everyday lives

- Study the similarities of hyperinflations throughout time

- Have a concrete idea of how to protect oneself from hyperinflations

A journey into the economy

This program aims to provide a deep understanding of the emergence of hyperinflations in a world dominated by Fiat currency and to examine their significant consequences. Participants will explore hyperinflation cycles in detail, analyzing the causes, triggers, and historical and contemporary examples. They will also examine the tangible impact of hyperinflations on the economy and daily life, studying the repercussions on currency value, purchasing power, and individual and collective savings.

Here, we will highlight trends and common patterns in episodes of hyperinflation throughout history, while providing effective and concrete strategies to protect oneself during hyperinflation periods. Participants will have the opportunity to explore various investment options and financial defense mechanisms, acquiring practical tools and essential knowledge to navigate calmly in an unstable economic climate.

Introduction

Course Overview

Welcome to the ECO204 course!

The goal of this course is to help you understand the root causes, mechanisms, and consequences of hyperinflation within the context of a fiat monetary system. Through concrete examples and historical analysis, you will learn to recognize recurring patterns that precede periods of hyperinflation and identify action levers to protect yourself.

Section 2: What is Inflation?

Before diving into the heart of the topic, we will revisit the basics: what is

inflation? This section will present its monetary origins, the different types

of inflation, and how they fit into a broader economic dynamic. This is an essential

step in understanding how regular inflation can evolve into hyperinflation.

Section 3: What is Hyperinflation?

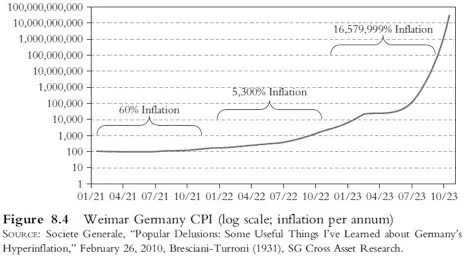

In this section, you will study precise definitions of hyperinflation and several

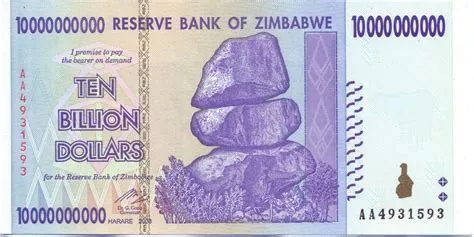

major historical episodes, including Weimar Germany and Zimbabwe. We will analyze

their commonalities, differences, and contemporary parallels. You will also discover

lesser-known cases, such as successive redenominations in Latin America, and

exit strategies observed in certain countries.

Section 4: How Did We Get Here?

This part aims to understand the structural mechanisms that make hyperinflation

possible, notably through the development of the monetary "second layer" and

the role of central banks. Additional resources and reading suggestions will

be provided for further exploration.

What if monetary history were repeating itself before our very eyes? You be the judge in the chapters that follow!

What is inflation?

A monetary phenomenon

Definitions of inflation

Inflation is a concept that is often misunderstood due to the multiple definitions associated with it. The perception of inflation varies among different groups such as bitcoiners and traditional economists. Let's first clarify the definitions before discussing hyperinflation:

Definition from Robert: Inflation is an excessive increase in payment instruments (banknotes, capital) causing a rise in prices and a depreciation of the currency.

Definition from Larousse: Inflation is a phenomenon characterized by a generalized and continuous rise in the level of prices. Here, the word "generalized" is crucial.

In light of these definitions, it is essential to understand that, for Robert, inflation mainly concerns the increase in the money supply. On the other hand, Larousse focuses on the consequences of this expansion, namely the generalized rise in prices.

In our study on hyperinflation, we will adopt the second definition, that of the generalized rise in prices, as it is more relevant and clear for our subject. However, it is crucial to remember that this rise in prices is generally the result of the expansion of the money supply. Renowned economist Milton Friedman famously stated:

"Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon."

This statement highlights the intrinsic relationship between monetary expansion and inflation. In the following sections, we will explore the interactions between inflation and economic growth, based on these fundamental definitions.

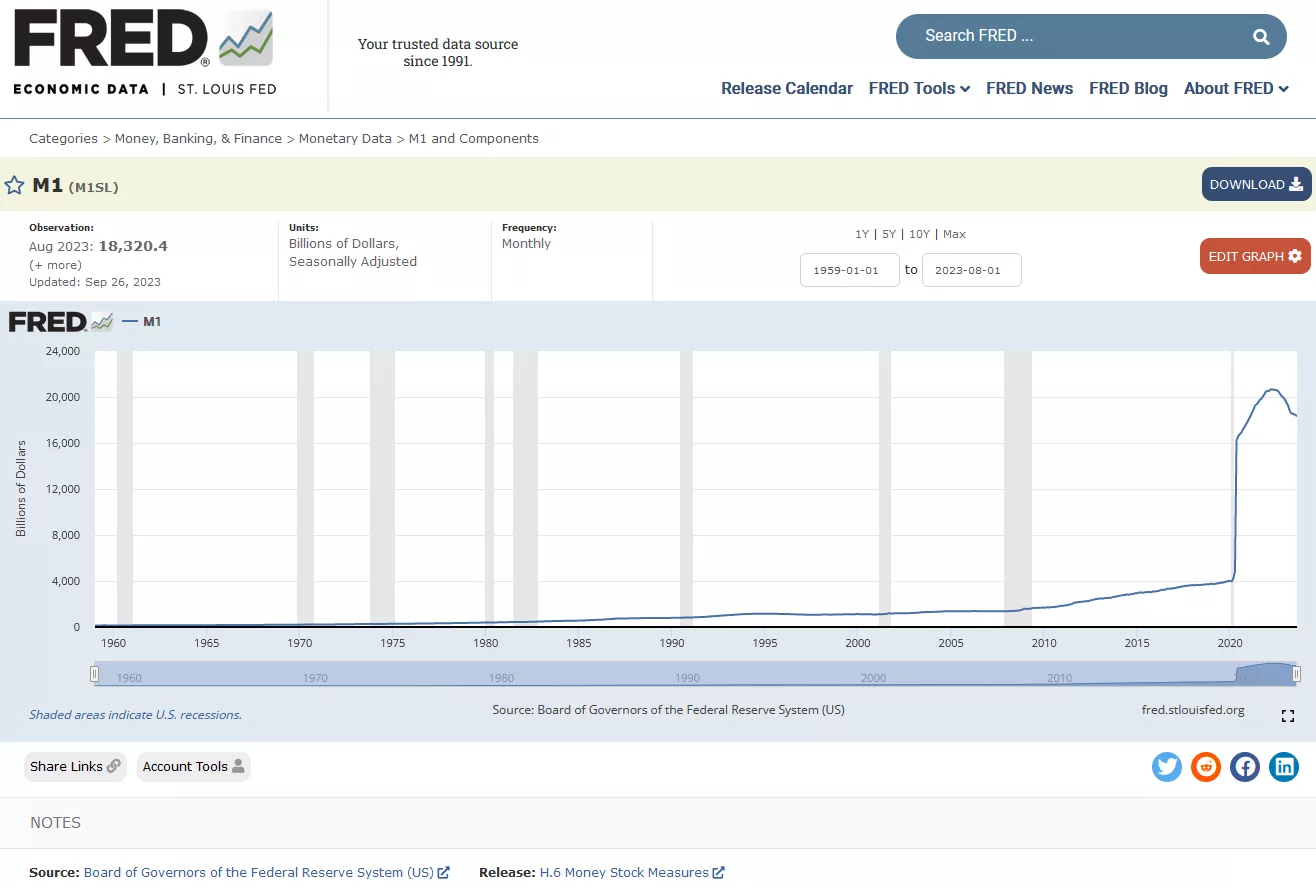

Understanding the Monetary Phenomenon

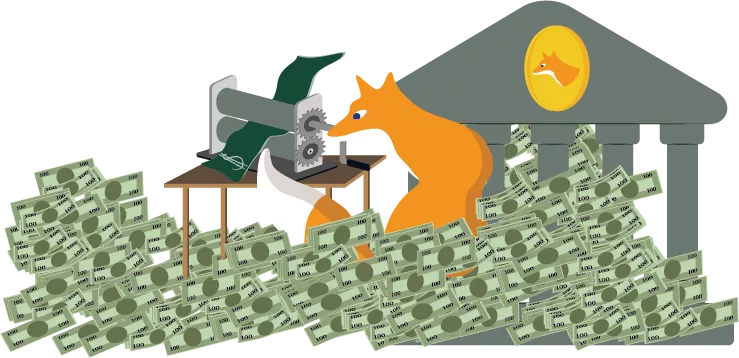

When referring to the monetary phenomenon, we are referring to how the money supply of an economy is influenced. Milton Friedman essentially saw it as an increase in this supply. Historically, there have been two main methods to increase the money supply:

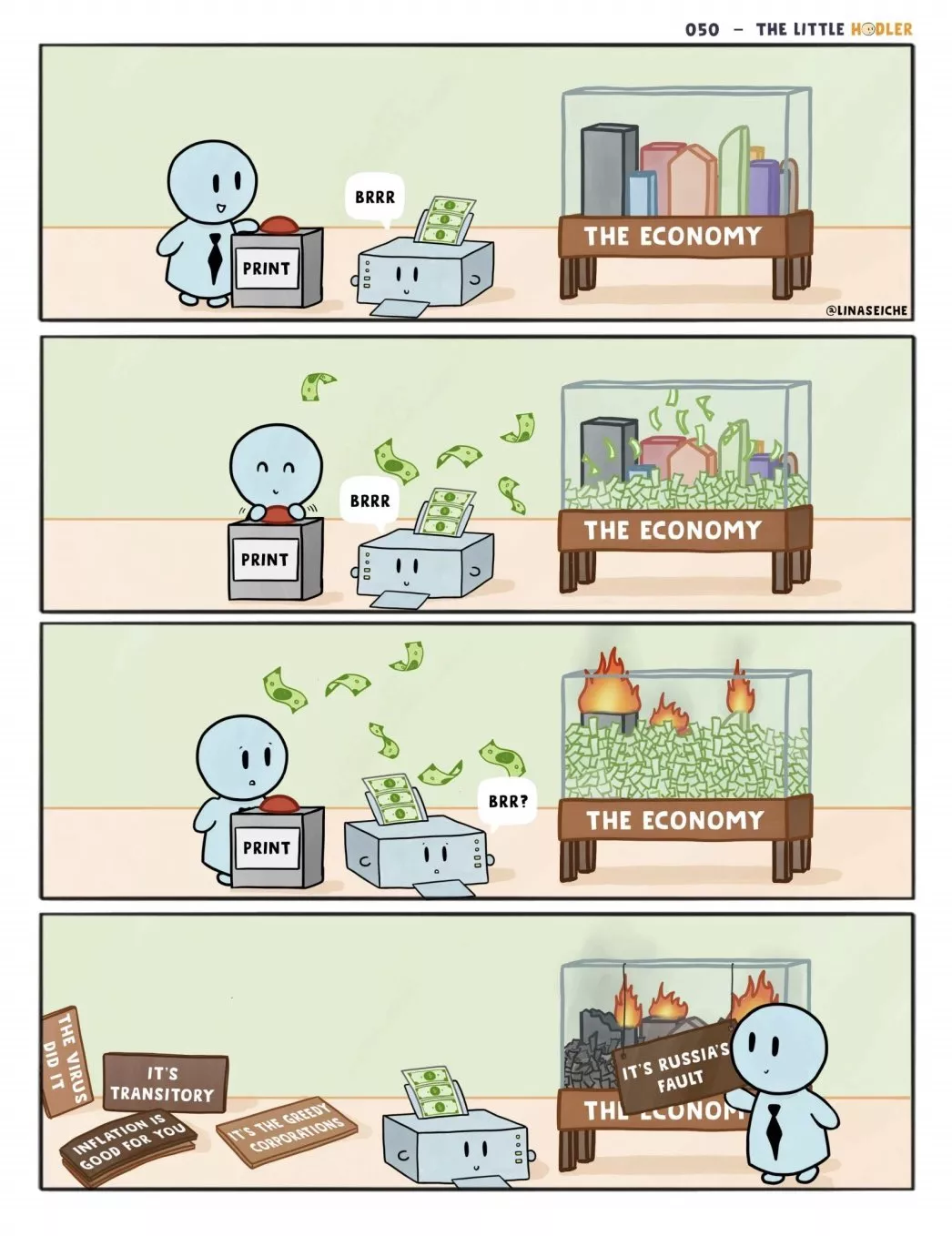

Monetary Printing: In traditional monetary systems, the increase in the money supply was achieved by physically printing new banknotes. Although nowadays, with the predominance of digital currency, this printing is mainly electronic (through the databases of central banks and other financial institutions), history shows us periods where the literal printing of banknotes led to hyperinflation.

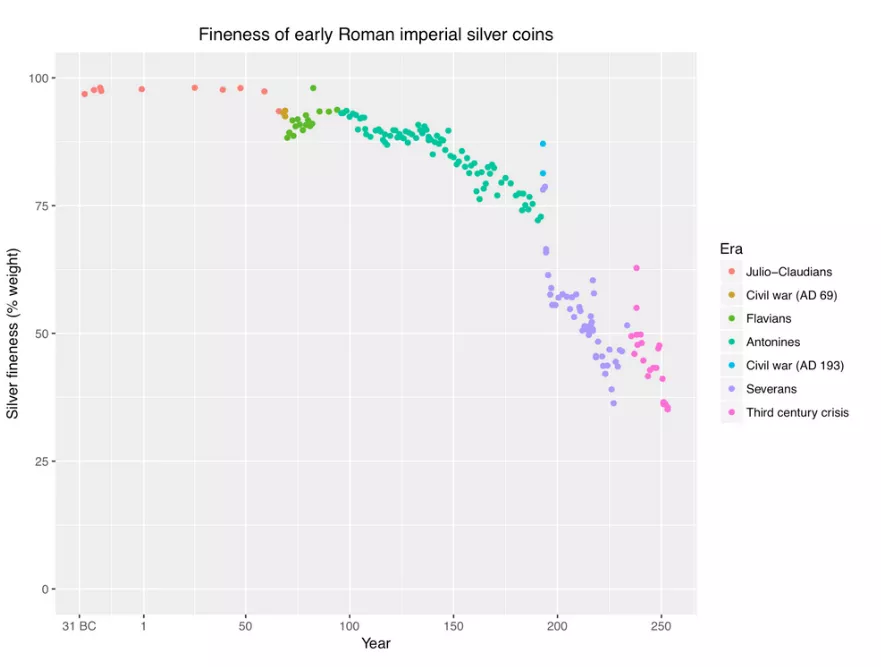

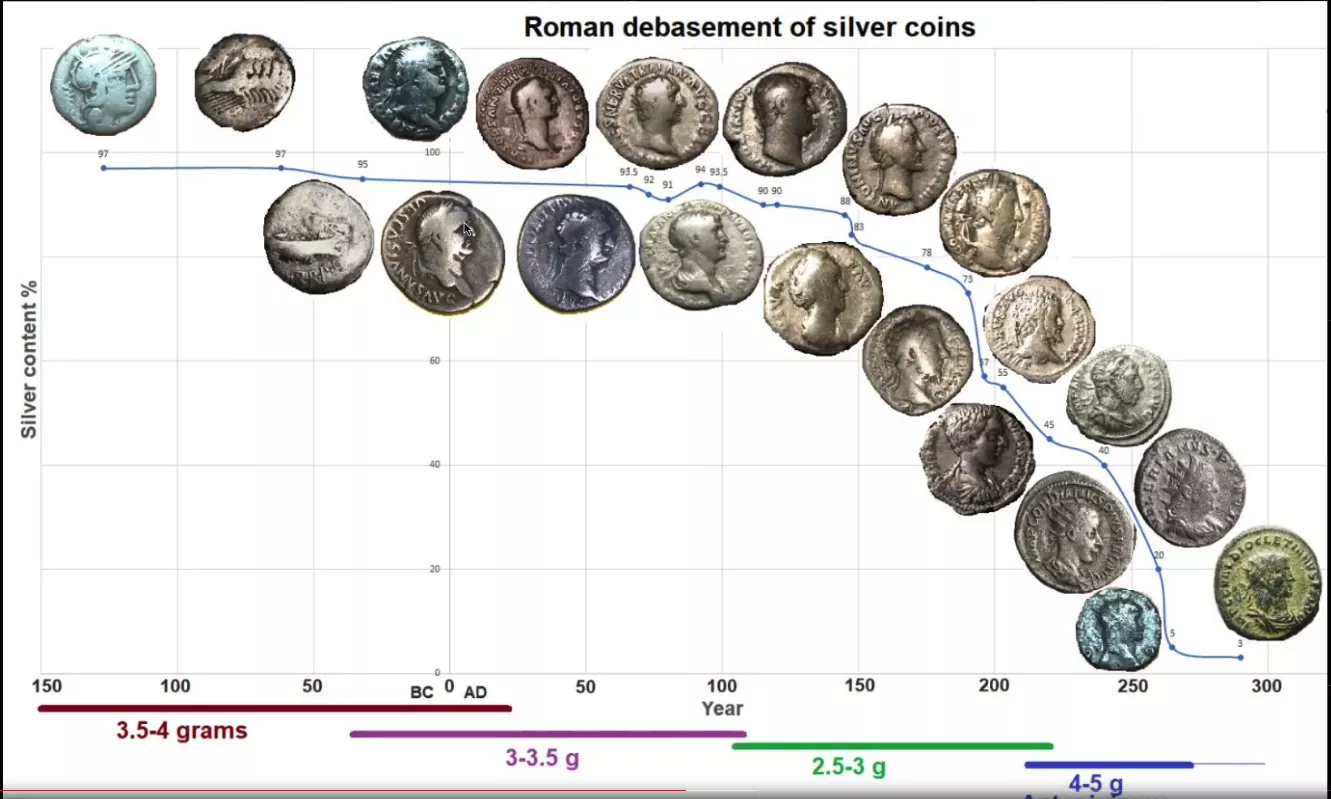

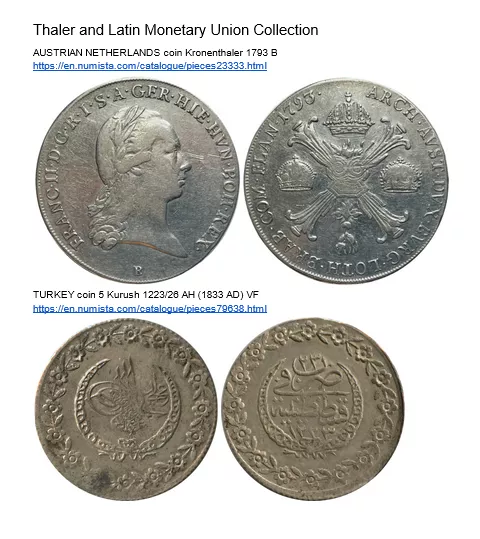

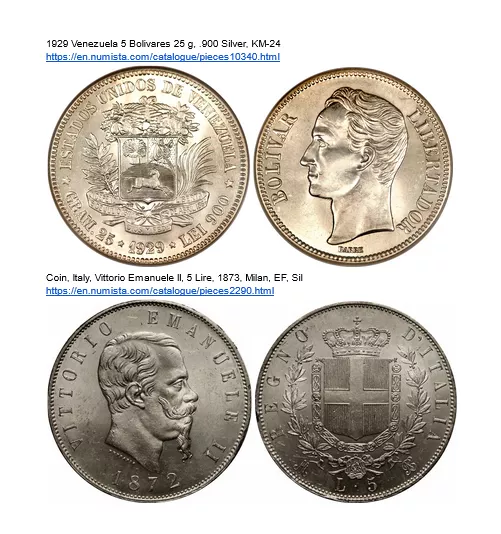

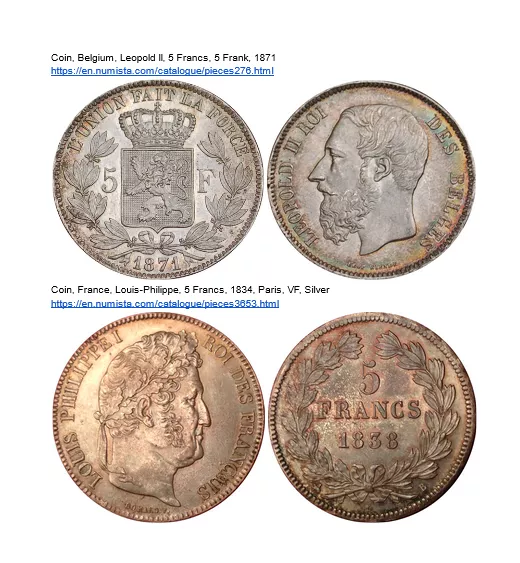

Reduction of Metal Content: Another method was to reduce the amount of precious metal in currencies based on metals such as silver or gold. A striking example can be found in the Roman Empire, where the denarius, initially composed almost entirely of silver, saw its silver content drastically reduced over time. This amounted to a form of inflation, but not necessarily hyperinflation.

It is crucial to emphasize that hyperinflation is mainly observed with fiat currencies disconnected from their underlying assets, such as precious metals. Historically, when a currency was based on such assets, there were episodes of inflation (e.g., through devaluation of the metal content), but these episodes never reached the extreme levels of hyperinflation. In the following sections, we will study in detail the periods of monetary devaluation and the implications of these different monetary systems on inflation.

Study of Periods of Monetary Devaluation

Throughout history, various civilizations have experienced periods of monetary devaluation. Some of these periods coincide with major events or wars that have put pressure on the economy.

1. Peloponnesian War and Second Punic War:

The Peloponnesian War, a conflict between Athens and Sparta, and the Second

Punic War, between the Roman Republic and Carthage, are the earliest

examples of currency devaluation found in the archives. To finance these

wars, these civilizations devalued their currencies by reducing the silver

content and incorporating other metals, while increasing the number of coins

produced.

Engraving depicting the massacre of the Athenians on the banks of the Assinaros.

2. Ancient Rome during the Empire:

After the era of the Roman Republic, during the Empire, the 3rd and 4th centuries experienced significant currency devaluation. This is illustrated by the decrease in the silver content of coins, as seen in the previous graph. A study shows that the price of wheat in Egypt, measured in drachma, increased by a factor of one million over a period of about 400 years, from 40 BC to 360 AD. Over this period, it represents an average annual inflation of about 4.4%. However, this inflation was not evenly distributed. It truly began around 238 AD. From 250 to 293 AD, the inflation rate was about 3.65%, and it increased to 22.28% between 293 and 301 AD.

Although these periods experienced significant inflation, they did not reach the levels of hyperinflation that we can observe in some modern situations. The reason for this is that, even though the currency was devalued, it was still based on precious metals. This solid foundation provided some protection against extreme levels of inflation. In the following sections, we will explore in more detail the nature and consequences of hyperinflation.

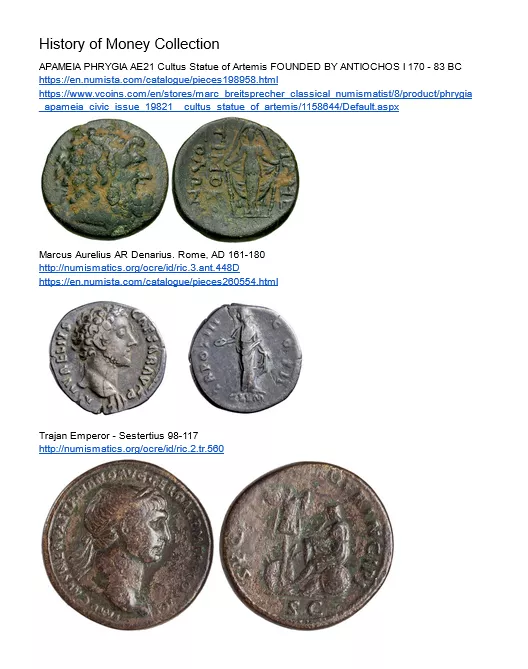

The Denarius of Marcus Aurelius (160 AD): One of the most iconic coins of ancient Rome is the denarius, a silver currency. I own a specific coin from Marcus Aurelius dating back to 160 AD, before the major devaluation. Although the camera may struggle to capture the fine details, to the naked eye, it can be seen that it is a beautiful silver coin, reflecting a relatively high silver content.

The Antoninianus (late 3rd century AD): With monetary devaluation, a new currency, the Antoninianus, appeared. This currency was supposed to be worth two denarii, but contained much less silver. My Antoninianus coin clearly shows that the silver content has been significantly reduced. It is adorned with a crown, typical of Roman coins of this period, called "radiates". By comparing the color and quality, it can be seen that the Antoninianus is far from being a pure silver coin. When comparing the two coins side by side, the difference is striking. The denarius from 160 AD has a distinct silver appearance, while the Antoninianus from the late 3rd century AD is much duller, indicating a significant decrease in silver content. This visual comparison provides a clear illustration of the monetary devaluation that ancient Rome underwent over a few centuries.

To complete this demonstration, a graph illustrating the devaluation of these coins over time would be ideal. Although difficult to visualize through this platform, imagine a graph showing the value of the denarius, then its decline towards the end of the 2nd century, replaced by the Antoninianus supposed to be worth two denarii but with a much lower silver content. These artifacts are silent witnesses to the economic fluctuations of past civilizations.

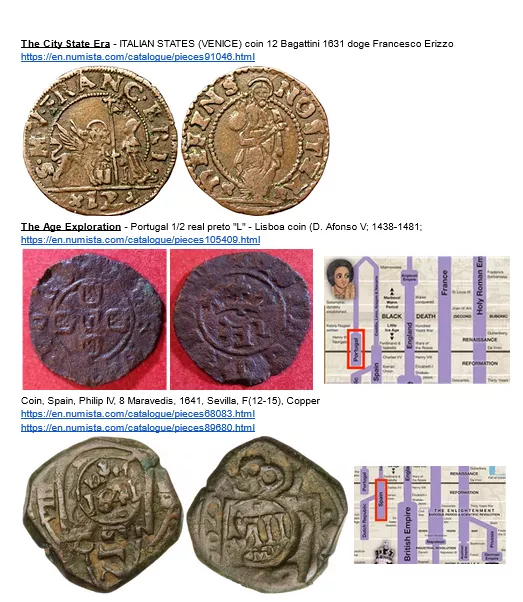

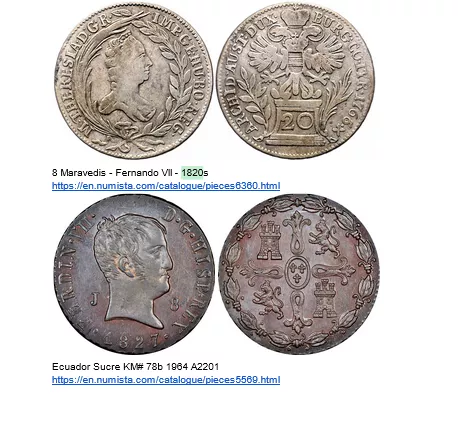

3. The Spanish Maravedi: Witness of Targeted Devaluation

The Maravedi, as a copper currency, occupies a special place in the history of Spanish currency. As mentioned earlier, the Spanish dollar was originally the international standard, an essential reserve currency for Spain. However, faced with certain economic challenges, Spain had to resort to clever monetary strategies.

Monetary devaluation is a tool often used by states to finance their expenses or stimulate the economy. However, Spain found itself in a delicate situation. Diluting the Spanish dollar would have compromised its position in international trade. To overcome this dilemma, Spain turned to the Maravedi.

Unlike the precious Spanish silver dollar, the Maravedis was a copper currency

mainly used within the local population. This currency was targeted for devaluation.

When a Maravedis coin was initially worth two maravedises, the state would retrieve

it, re-stamp it with a new value, for example "four", and only return one coin

to the owner. The coin mentioned with the stamp "eight" is evidence of this process,

having undergone several cycles of devaluation.

Unlike the precious Spanish silver dollar, the Maravedis was a copper currency

mainly used within the local population. This currency was targeted for devaluation.

When a Maravedis coin was initially worth two maravedises, the state would retrieve

it, re-stamp it with a new value, for example "four", and only return one coin

to the owner. The coin mentioned with the stamp "eight" is evidence of this process,

having undergone several cycles of devaluation.

This strategy allowed the state to effectively devalue a currency, creating inflation and indirectly financing itself, while preserving the integrity of the Spanish dollar on the international stage. However, this targeted devaluation had consequences for the local population, who saw the value of their common currency diluted.

The case of the Maravedis illustrates how a state can selectively devalue a local currency to meet its internal economic needs, while preserving the value of a reserve currency on the global stage. It is a striking example of the complexity and finesse of monetary policy in history.

More about what? -> Link

4. Price Revolution from the 15th to the 17th Century

Between the 15th and 17th centuries, Europe witnessed a remarkable economic phenomenon, often referred to as the "price revolution." This period of inflation was largely triggered by a massive influx of precious metals, particularly gold and silver, from the Americas. With the European economy largely based on the metallic standard at the time, this additional supply of metals increased the money supply. As a result, an inflation rate of about 1 to 2% per year emerged. At first glance, this inflation may seem modest. However, at that time, such price fluctuations were unusual enough to be considered a "revolution." This highlights how changes in monetary reserves can influence the entire economic system.

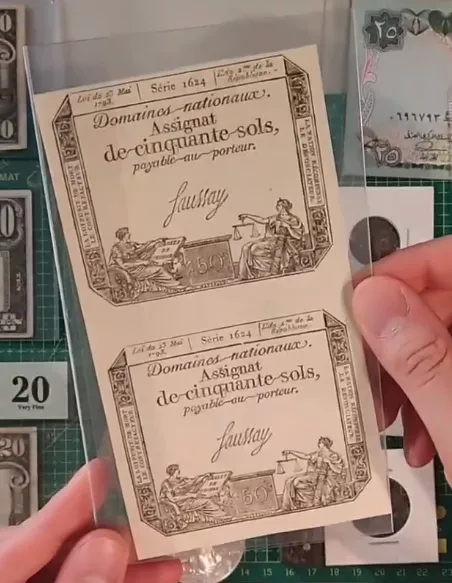

5. John Law and the Assignats

In the 18th century, French economic history was marked by two significant events related to currency. First, John Law, a Scottish economist and financier, persuaded the French government to adopt a monetary system based on paper money. Although initially considered an innovative solution to the country's financial problems, this initiative quickly led to rampant inflation. Then, shortly after, during the turmoil of the French Revolution, the government introduced "assignats".

Assignats from 1793

These banknotes are a living testimony to the first major period of hyperinflation in history. Initially designed as a response to successive financial crises, assignats quickly became a symbol of monetary instability. The government, relying excessively on this paper currency to finance its expenses, caused an unprecedented economic crisis and created a major period of hyperinflation in France after the revolution.

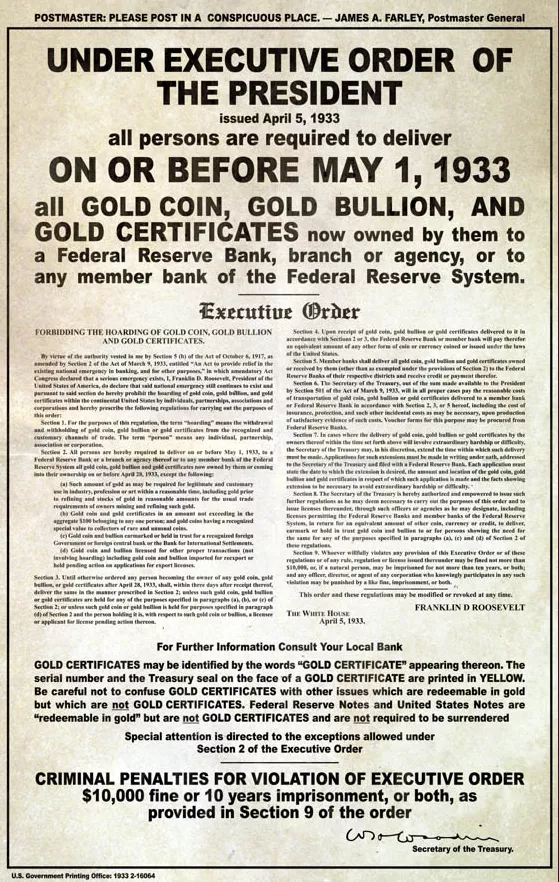

6. Executive Order 6102 and the Devaluation of the Dollar

Executive Order 6102 and the Devaluation of the Dollar

In the United States, the early 1930s witnessed a major shift in monetary policy. Here is a detailed overview of this transformation:

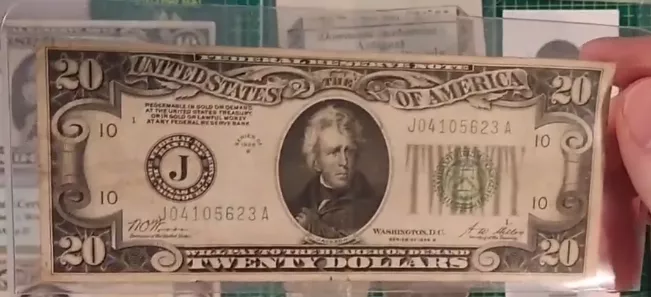

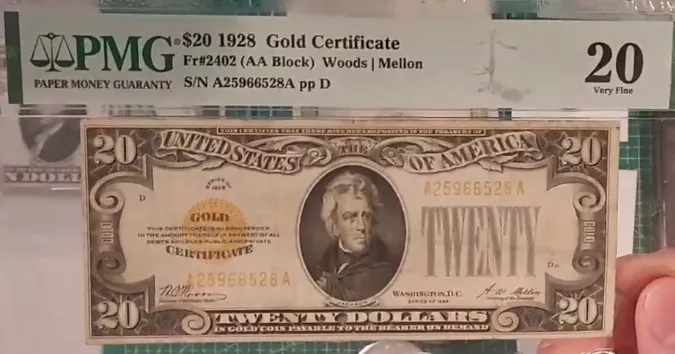

- The 1928 $20 Bill

In 1928, a 20 bill in the United States stated: "redeemable in gold on demand." This

means that each bill was literally convertible into gold. Specifically, a20.67 bill was equivalent to one ounce of gold.

- Executive Order 6102

In 1933, a major upheaval occurred with the issuance of Executive Order 6102. This decree made it illegal for citizens to possess gold, whether in the form of bars, coins, or certificates.

The Gold Certificate is a good example. It was marked: "In gold coin payable to the bearer on demand." Possessing such a certificate became illegal and remained so until 1964.

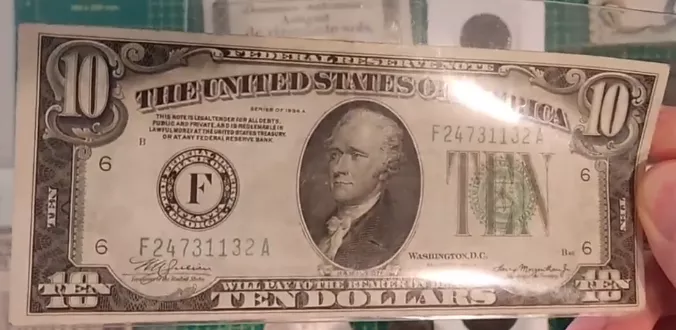

- Introduction of New Banknotes

Following the seizure of gold in 1934, a new series of banknotes was put into circulation.

The mention indicating their convertibility into gold has been removed and replaced

by "This note is legal tender for all debt" (Ce billet est une monnaie légale

pour toutes dettes).

The mention indicating their convertibility into gold has been removed and replaced

by "This note is legal tender for all debt" (Ce billet est une monnaie légale

pour toutes dettes).

- Gold Revaluation

What is fascinating about this transition is the government's strategy. In

1934, the price of gold was revalued to 35 per ounce, instead of20.67. Essentially, the government devalued the dollar that people

owned. By buying gold from the population at $20.67 per ounce in 1933, and

then revaluing the price of gold in 1934, the government made a substantial

profit while devaluing its citizens' savings.

In summary, within a year, the government effectively seized citizens' gold, then changed the rules of the game by revaluing the value of gold to benefit the treasury and disadvantage those who had initially exchanged their gold for notes.

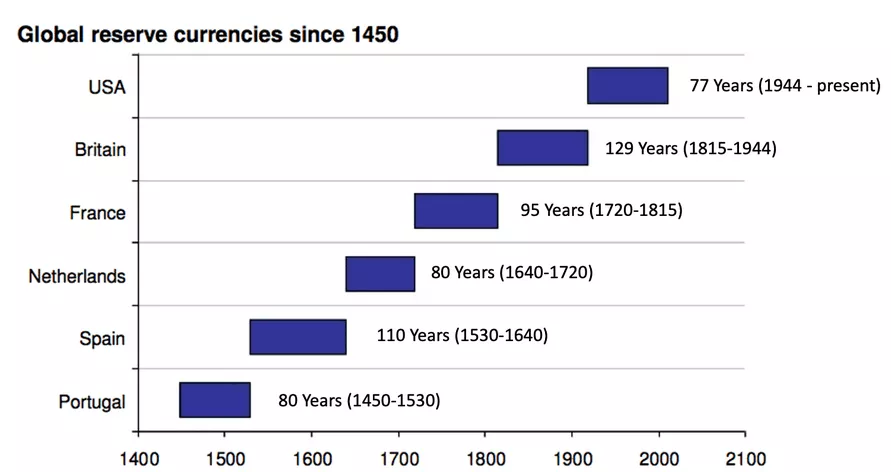

The US changes history.

The United States made a historic turning point by becoming the first to devalue the world reserve currency, the US dollar, contrary to previous practices observed in small trading nations.

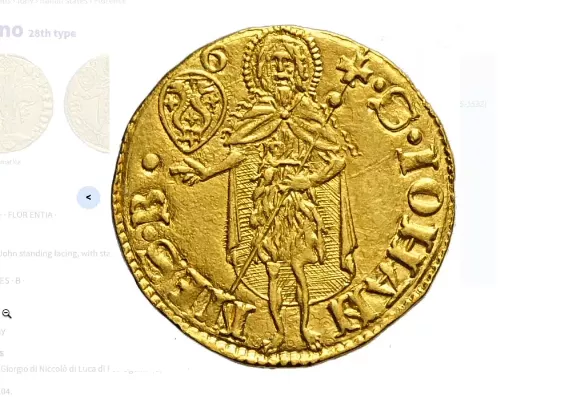

Previously, during the Renaissance, the Italian florin issued by Florence in the 13th century was the international reserve currency, and no devaluation had been recorded during its period of use, reflecting the importance of monetary stability for international trade.

In the same spirit, Spain and the Netherlands, as holders of the world reserve currency due to their flourishing international trade, maintained the integrity of their currency to preserve confidence and the status quo in international exchanges. The Netherlands even witnessed the creation of the first central bank, a crucial milestone in global monetary evolution.

However, the situation changed with the rise of the United States as the dominant economic power. They chose to devalue their reserve currency, thus exploiting inflation to their advantage. This decision is often attributed to the changed dynamics, where the choice of reserve currency was no longer as free as before. American hegemony established the dollar as the world reserve currency, allowing for manipulation of its value. This shift reveals the potential impact of monetary policies on international trade in a globalized economy, marking a significant transition in the management of global reserve currencies.

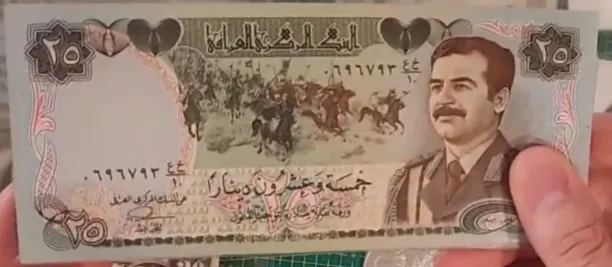

Last example for the road: the Swiss Dinner

The Swiss Dinar illustrates another fascinating aspect of monetary

devaluation, this time anchored in the pre-Gulf War Iraqi context. Named

after the notable quality of its banknotes, this currency was issued by the

Central Bank of Iraq and enjoyed a reputation for stability in the Middle

East region. This confidence was mainly due to the quality of the banknote

printing, which was done in England, implying a certain robustness against

devaluation.

However, the Gulf Wars marked a turning point in the history of the Swiss Dinar. Iraq, no longer able to rely on its English supplier for banknote printing, turned to China. This transition resulted in a clear difference in the quality of the banknotes, with the Chinese version being perceived as inferior. This perception was not unfounded; the Chinese banknotes were more easily counterfeitable and susceptible to overprinting by the government, thus threatening their value.

A distinctive phenomenon emerged in the post-Gulf War Iraqi economy: the dual pricing system. Merchants offered different prices depending on the type of banknote used for payment, favoring the original Swiss Dinar over the Chinese banknote. This system reflected the maintained trust in higher-quality banknotes, which were less prone to devaluation, even in a context where value was primarily imposed by the state. This episode demonstrates the importance of intrinsic characteristics of currency and how, even in a fiat currency regime, the perceived quality of a currency can influence its relative value and, by extension, the confidence of economic actors.

Yes, we actually weighed the coins!

The common perception often associates currency with state creation, where its issuance and value are regulated by the state. This concept has its roots in ancient civilizations such as Rome, where coins were standardized and stamped by the Empire, thus conferring official value to the currencies. However, a deeper exploration reveals that the intrinsic value of currency was mainly derived from its precious metal content.

An example is illustrated through the examination of a monetary weight equivalent

to eight Spanish reales, or one Spanish dollar. This weight, marked with a Roman

numeral indicating its value, was used by currency exchangers to evaluate the

value of coins based on their weight, rather than just their stamping. By weighing

the coins, the exchangers could determine if they had been altered or damaged,

which could have reduced their value. This practice highlights that, although

the standardized stamping by the state conferred a certain nominal value to the

currency, the true value resided in the weight of the precious metal it contained.

An example is illustrated through the examination of a monetary weight equivalent

to eight Spanish reales, or one Spanish dollar. This weight, marked with a Roman

numeral indicating its value, was used by currency exchangers to evaluate the

value of coins based on their weight, rather than just their stamping. By weighing

the coins, the exchangers could determine if they had been altered or damaged,

which could have reduced their value. This practice highlights that, although

the standardized stamping by the state conferred a certain nominal value to the

currency, the true value resided in the weight of the precious metal it contained.

This analysis demonstrates that trust in currency, and by extension its value, was anchored in its tangible substance rather than the mere assertion of the state. It underscores the duality between the nominal value imposed by the state and the intrinsic value dictated by the content of precious metal. Thus, currency goes beyond being a mere state instrument, with its fundamental value being intrinsically linked to tangible and measurable elements.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study on monetary devaluation opens the door to a deep understanding of inflation mechanisms, which will be explored in the following videos. We will discuss the different types of inflation and the threshold at which they transition to high or hyperinflation. This solid foundation will allow us to address the complexities of inflation in the upcoming sessions. Thank you for your attention, and see you in the next video to continue this exploration of monetary dynamics.

Types of Inflation

Inflation is not a multifactorial phenomenon

In this section, we will explore the different dimensions of inflation, a phenomenon that is often misunderstood. Although inflation is frequently perceived as a multifactorial phenomenon in the media and everyday discussions, it is crucial to remember that it is fundamentally a monetary phenomenon.

Here is a breakdown of the topic into several key points:

Distinction between Price Increase and Inflation:

A price increase can be sector-specific and induced by various factors such as a decrease in OPEC production for oil or unfavorable weather conditions for wheat. Inflation, on the other hand, is defined by a generalized increase in prices across a range of goods and services, not just in a specific sector.

The Monetary Essence of Inflation: With a fixed money supply, an increase in prices in one sector would result in a decrease in prices in other sectors, as the amount of money available to spend elsewhere would be reduced. Inflation is closely related to an increase in the money supply, which allows for a simultaneous increase in prices in all sectors.

Impact of Money Supply on Inflation and Deflation:

In a fixed money supply system, an increase in production should theoretically lead to deflation, i.e., a decrease in prices, as there would be more goods and services available. In the current fiat monetary system, an increase in the money supply cancels out the potential deflation caused by an increase in production.

Negative Effects of Money Supply Adjustment:

An increase in the money supply, without a corresponding increase in production, leads to inflation, as there is more money in circulation for the same amount of goods and services. While the increase in production should have led to deflation, the simultaneous increase in the money supply nullified this effect, resulting in inflation instead.

Inflation, Deflation, and Money Supply: Communicating Vessels:

Inflation and deflation are like communicating vessels in an economy. An increase in production can lead to deflation, but if the money supply is increased simultaneously, the deflationary effect is canceled out, resulting in inflation.

This discussion highlights the importance of understanding the underlying mechanisms of inflation and deflation, and how manipulating the money supply can have profound impacts on the economy. We will likely revisit these concepts later for a deeper understanding of their interconnectedness and their impact on the global economy.

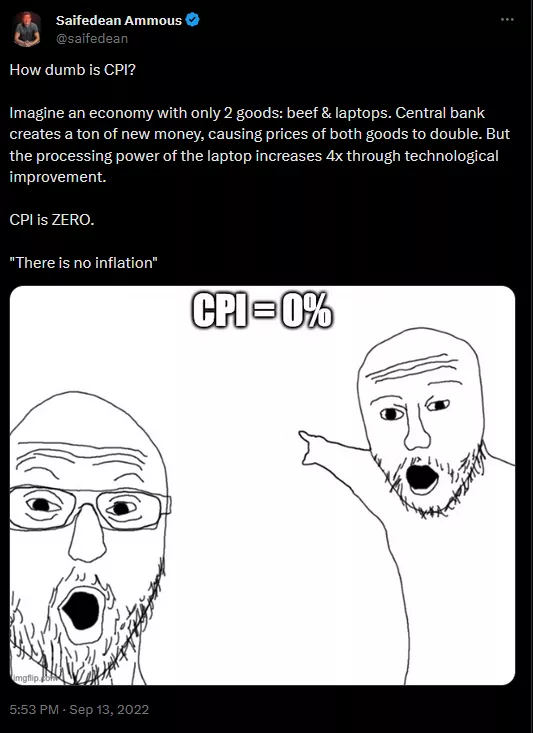

Why does money printing not always cause inflation?

Inflation ≠ CPI

Inflation, although often associated with an increase in the money supply, does not always have a direct correlation with money printing, as illustrated by the period following the 2008 financial crisis. Despite significant money printing to save the banks, the following decade did not experience high inflation, averaging between 0 and 2% per year. This situation raises the question: why did massive money printing not result in proportional inflation? The answer lies in several nuances related to measuring inflation and the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The first explanation lies in the way inflation is measured. The Consumer Price Index (CPI), used as the main indicator of inflation, has certain limitations. For example, it does not comprehensively take into account the evolution of real estate prices. Although the CPI includes a component related to rents, the substantial appreciation of house prices is not fully reflected. As a result, significant increases in housing costs can occur without being fully captured by the CPI, potentially underestimating actual inflation.

In addition, the calculation of the CPI includes certain methodologies that can offset or mask actual price increases. For example, qualitative improvements in products can be used to adjust the index. If the price of a product increases, but its quality or features also improve, the CPI may consider that the real value for the consumer has not changed, and therefore not reflect inflation. An illustrative case is one where, despite an increase in beef and computer prices due to monetary injection, the improvement in computer performance is used to offset this increase. If a computer costs twice as much but is four times more powerful, the CPI may interpret this as a decrease in prices, thus masking the increase in beef prices.

These nuances in measuring inflation by the CPI highlight the complexity of the relationship between monetary printing and inflation. They also suggest that actual inflation may be higher than reported if all price increases, especially in key sectors such as real estate, were more comprehensively taken into account. This analysis highlights the importance of understanding the underlying mechanisms of inflation and the limitations of conventional indices used to measure it, in order to better understand the economic impact of monetary policies.

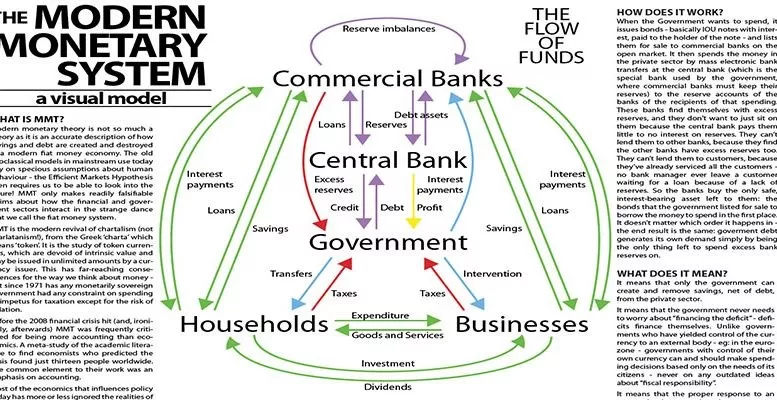

Arguments of MMT

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) offers a distinct perspective on money creation and inflation. According to MMT, money primarily originates from the government, which can print substantial amounts to finance its needs without causing inflation as long as the sectors targeted by these funds are not saturated. This is an approach that deviates from traditional monetary theories and emphasizes the importance of sectoral absorption capacities in the inflationary dynamics.

An illustrative example of MMT is the American military-industrial complex. According to MMT, hundreds of billions of dollars can be allocated to this sector without causing inflation, thanks to its absorptive capacity. In contrast, if substantial funds are injected into road construction in the United States, where there is a limited number of companies and labor, inflation could occur due to resource scarcity and increased costs demanded by suppliers. Japan is often cited by MMT proponents as another example of the absence of inflation despite significant monetary printing. However, the situation in Japan also highlights the limitations of traditional measures of inflation such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI). In Japan, a large portion of the printed money is either saved or invested in real estate or stock markets, rather than spent in the current consumption economy. The CPI, by not fully capturing these dynamics, may underestimate actual inflation.

The analysis of Japan (https://ideas.repec.org/p/ces/ceswps/_9821.html) also highlights that the behavior of economic agents, such as saving or investing in assets not included in the CPI, can mask the inflationary impact of monetary printing. Furthermore, the ability of different sectors to absorb injected liquidity plays a crucial role in whether or not inflation occurs.

Bank and Central Bank Balance Sheets

A third example of why monetary printing would not cause inflation is that the relationship between monetary printing and inflation is modulated by how newly created money is introduced into the economy. If this money remains on the balance sheets of private banks without being lent to economic actors, it will not directly impact the real economy and, therefore, will not result in inflation.

Monetary printing can be seen as a sword of Damocles hanging over the economy. The created money can remain latent for a certain period of time, without any visible inflationary effect, as long as it is not injected into the economy through bank loans or other mechanisms. However, when this latent money is finally put into circulation, inflationary effects can then manifest. This is what has been observed in the 2020s, where previously created money has found its way into the economy, leading to inflation. This scenario highlights the importance of monetary transmission mechanisms in determining the inflationary impact of money printing. Central bank money creation is just one piece of the puzzle. The behavior of private banks, who decide on the volume of loans to grant, and the behavior of borrowers, who decide how they will spend the borrowed money, are also crucial elements in this dynamic.

Inflation is social!

The example of the Weimar Republic illustrates another crucial aspect of the relationship between money printing and inflation: the role of expectations and the behavior of economic agents. When the Central Bank of the Weimar Republic began printing a large amount of money, economic uncertainty led individuals to hoard, i.e., store money rather than spend it. This reaction temporarily delayed the inflationary effects of money printing.

However, when the economic situation began to improve slightly, confidence gradually restored. Individuals then withdrew their savings from their hiding places and started spending massively in the economy. This sudden change in behavior, combined with an already high money supply, led to an explosion in demand. With more money in circulation and increased demand, prices began to rise rapidly, leading to noticeable inflation.

This example highlights the importance of timing and agent behavior in the manifestation of inflation. Inflation does not only occur in response to an increase in the money supply, but also depending on how and when that money is spent in the economy. Economic uncertainties and the expectations of economic agents play a crucial role in this dynamic and can either accelerate or delay the inflationary effects of money printing.

Recap:

Consumer Price Index (CPI): The CPI is structured in a way that underestimates inflation, which can give a distorted picture of the inflationary reality.

Sectoral Absorption: Monetary injection into sectors capable of absorbing it does not always lead to inflation. The main example is the US military-industrial complex, which can absorb large sums of money without causing inflation.

Case of Japan: Despite significant money printing, inflation remains low in Japan because funds are often saved or invested in real estate or stock markets. These sectors absorb the printed money, and the CPI does not necessarily reflect price increases in these areas.

Correlation between Monetary Printing and Markets: It is observed that the curves of real estate and stock markets often follow monetary printing, indicating where the printed money is directed.

Monetary Reserves of Banks: When printed money remains on the balance sheets of banks and does not circulate in the economy, it does not cause inflation. This is illustrated by the example of 2008, where printed money largely remained on the balance sheets of banks, delaying the inflationary impact.

Weimar Republic: This historical period shows how economic uncertainty led to hoarding of money, delaying inflation. However, once confidence was restored and money was spent, inflation exploded.

These examples can be used in discussions to explain why inflation is not always an immediate consequence of monetary printing, and how economic contexts and agent behaviors influence inflation.

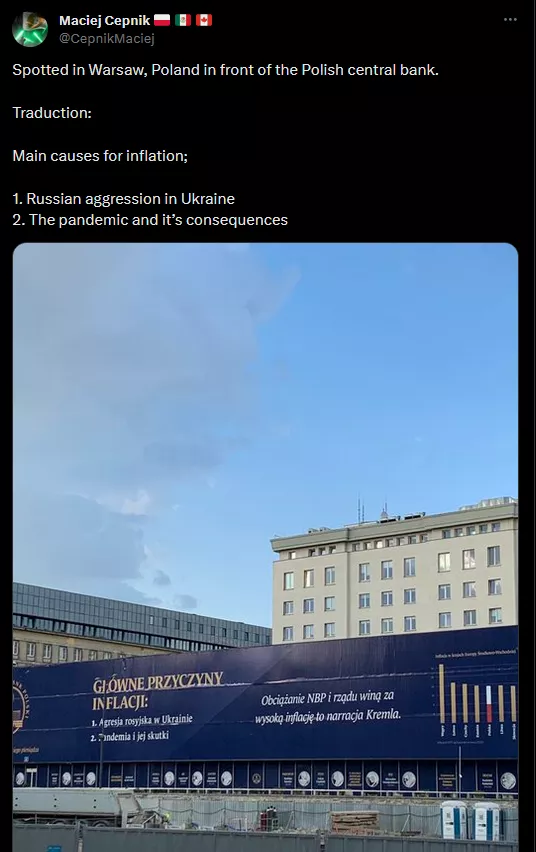

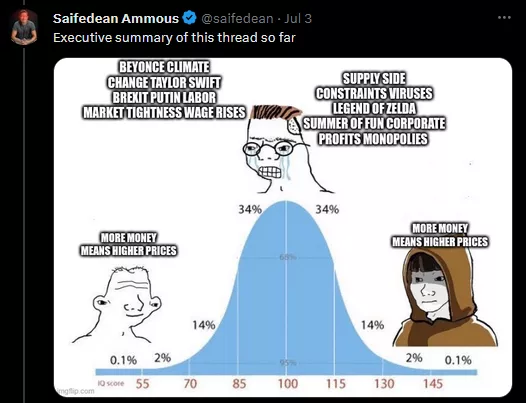

Because, as this thread shows: Inflation is everything except the fault of central banks.

- Economists blaming inflation on climate change

- Example of Sweden blaming Beyoncé for inflation during a specific month.

- Central bank in Poland attributing inflation to Russian aggression in Ukraine and the pandemic

- Brexit blamed for inflation in the United Kingdom.

- Release of the Zelda game associated with an inflationary shock.

- Taylor Swift allegedly causing inflation.

How could Beyoncé or Taylor Swift, tell me, explain a widespread rise in prices? You see, it doesn't make any sense. In short:

Exploration of Types of Inflation

It is crucial to understand the distinction between different types of inflation, an understanding that allows us to grasp the varied manifestations of this economic phenomenon. Here is an explanation of these different types:

Creeping Inflation: This is the type of inflation that central banks generally aim for, set at around 2% annually. This target has been adopted since the 1990s and aims to maintain stable economic growth without overheating or deflation.

Moderate Inflation: This form of inflation occurs when inflation exceeds the target of 2%. It is often associated with an overheating economy, a state where excessive money supply stimulates a general increase in prices. This scenario exposes the limits of monetary policies and sometimes reveals contradictions in economic discourse.

Galloping Inflation: Galloping inflation, often referred to as double-digit inflation, occurs when the annual inflation rate exceeds 10%. It marks a significant price surge that can compromise economic stability.

Hyperinflation: Hyperinflation is an extreme phenomenon where the inflation rate exceeds 50% per month, which, due to the exponential nature of inflation, is equivalent to an annual inflation rate of over 13,000%. This level of inflation severely destabilizes the economy, rendering the currency almost worthless and causing a loss of confidence in the monetary system.

When exploring types of inflation, it is common to come across terms like "Demand Pull" and "Cost Push" in educational resources. These concepts, although valid, tend to explain price increases rather than inflation as a monetary phenomenon. Here is a more in-depth analysis:

Demand Pull: Demand Pull inflation is often explained as a situation where demand in the economy exceeds available production. However, without a corresponding increase in the money supply, this situation will simply lead to a redistribution of spending. Consumers may spend more on essential goods and less on others, thus neutralizing the overall inflationary effect.

Cost Push: On the other hand, Cost Push inflation is attributed to the increase in production costs, such as those of natural resources or labor. Again, without an increase in the money supply, cost increases in one sector may simply reduce spending in others, without causing widespread inflation. These traditional explanations often associate price increases with inflation, which can be confusing. In reality, for widespread inflation to occur, an increase in the money supply is necessary. In this context, the concepts of Demand Pull and Cost Push can explain sectoral price variations, but they do not capture the monetary nature of inflation. This highlights the importance of distinguishing between sectoral price increases and widespread inflation, and reaffirms the need for an increase in the money supply for inflation to manifest throughout the economy. This analysis offers a more nuanced and precise perspective on the real causes of inflation and demystifies common interpretations that may mask the underlying monetary dynamics.

Classification of Inflation according to Bernholz

Bernholz proposes a simplified but precise classification of inflation into three categories, allowing for a better understanding of this complex monetary phenomenon:

Moderate Inflation: Moderate inflation occurs when the level of money supply is higher than normal, but without the state resorting to large deficits financed by money creation. Although the term "moderate" may seem insignificant, this form of inflation can cause substantial problems, although it is not classified as high inflation.

High Inflation: High inflation occurs when the real value of the money supply decreases despite an increase in nominal terms. This paradoxical situation arises from monetary substitution, where individuals lose confidence in the national currency and seek to exchange it for goods, services, or foreign currencies. This process further reduces the real value of the currency, exacerbating inflation.

Hyperinflation: Hyperinflation is an extension of high inflation, characterized by large budget deficits financed by money creation. Historically, no case of hyperinflation has been observed without substantial deficit financing through money printing. Hyperinflation creates a vicious cycle: inflation erodes the value of the currency so rapidly that tax revenues depreciate before the state can even collect them, thus forcing the state to print even more money to finance itself. This self-reinforcing cycle leads to astronomical inflation rates, often exceeding 50% per month. This classification by Bernholz highlights the dangerous progression from moderate inflation to hyperinflation, emphasizing the crucial importance of monetary and budgetary control in preventing destructive inflationary spirals. It also demonstrates that the detrimental consequences on state financing can occur well before reaching the stage of hyperinflation, providing a nuanced perspective on the implications of inflation at various degrees.

Conclusion: Summary of Inflation Types

In conclusion, we have explored a range of inflation types, starting with commonly heard terms such as "creeping inflation," "walking inflation," and "galloping inflation," each denoting different levels of inflation percentages within an economy. However, for our in-depth study on hyperinflation, the categories of moderate inflation, high inflation, and hyperinflation, as described by Bernholz, prove to be crucial benchmarks.

Moderate Inflation: It indicates a level of money supply above normal, although this level can be sustained without significant deficit financing by the state.

High Inflation: It occurs when the real value of the money supply decreases, often due to monetary substitution, where individuals seek to exchange their currency for goods, services, or other currencies.

Hyperinflation: It represents an extreme version of high inflation, where excessive money creation to finance large budget deficits leads to a rapid erosion of the real value of the currency.

What emerges from our exploration is that hyperinflation is a complex and counterintuitive phenomenon. While one might assume that hyperinflation is the result of a massive increase in the money supply, in reality, it stems from a decrease in the real value of that money supply. This nuance is crucial to understanding why some countries struggle to emerge from hyperinflation, even with the support of international institutions such as the World Bank or the IMF. Mischaracterizing the type of inflation can lead to the application of inappropriate remedies, exacerbating economic problems instead of resolving them.

In our future discussions, we will delve deeper into hyperinflation, exploring its definitions and manifestations in various economic contexts. Our goal will be to uncover the underlying mechanisms of hyperinflation and explore potential solutions to address it. This nuanced understanding will enable us to better grasp the associated challenges and propose informed strategies for inflation management. Thank you for your attention. The next session will be entirely dedicated to defining and demystifying hyperinflation, taking into account different academic and practical perspectives. We look forward to continuing this exploration with you in our next meeting.

What is hyperinflation?

Definitions of hyperinflation

Definitions of hyperinflation

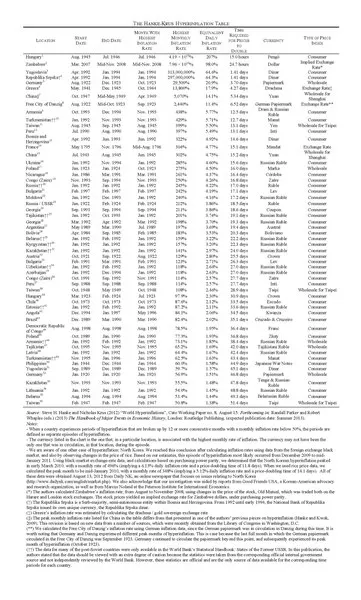

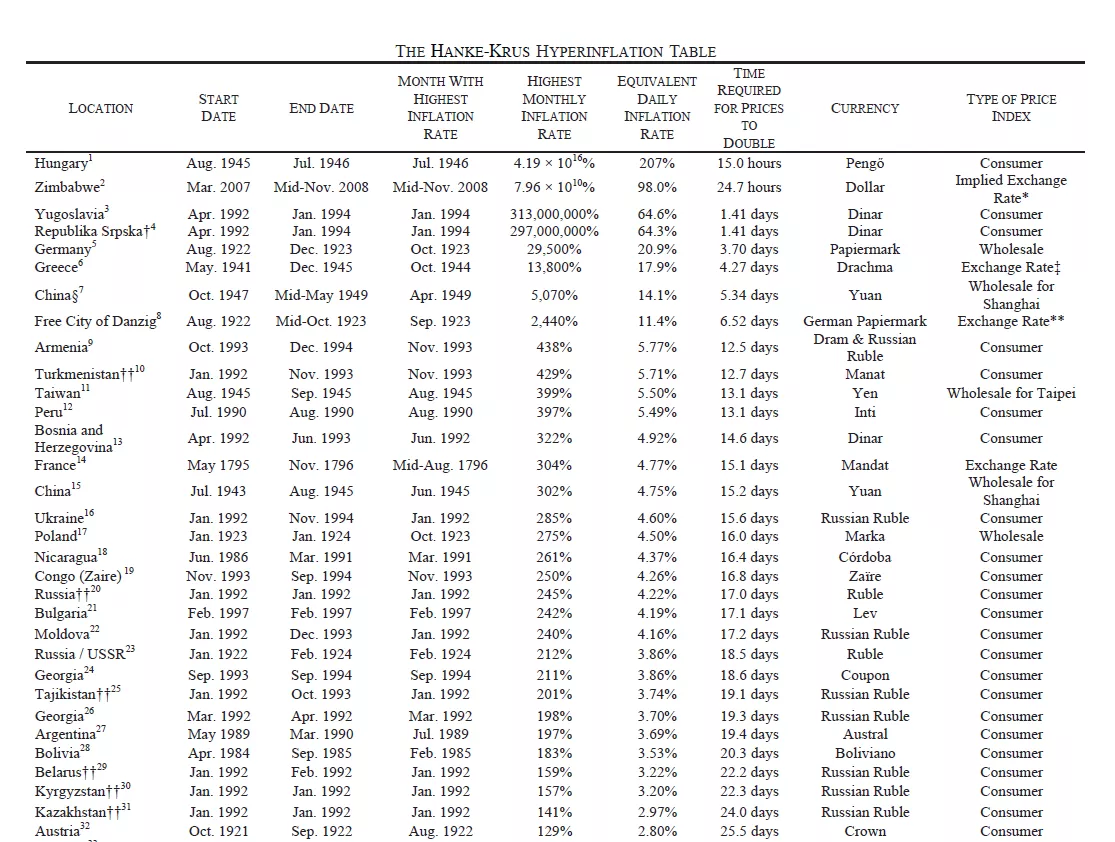

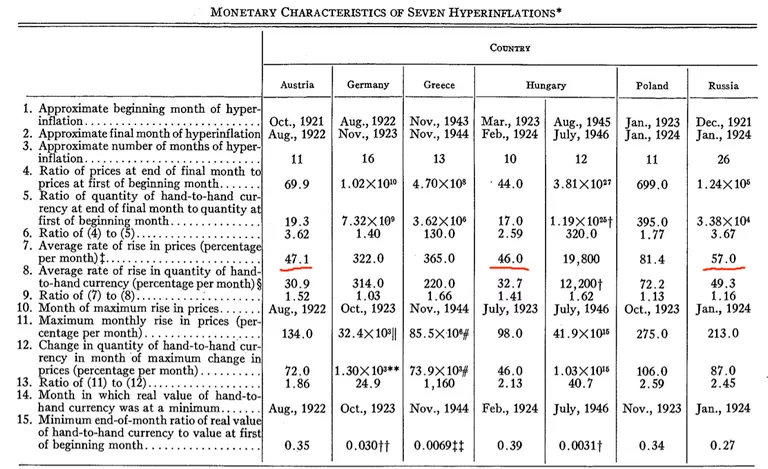

In this section, we explore the various definitions of hyperinflation, a crucial term in the study of extreme monetary phenomena. The most recognized definition comes from Philip Cagan, who, in his 1956 work, "The Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation," proposes a quantitative understanding of hyperinflation. According to Cagan:

- Beginning and End of Hyperinflation:

- Hyperinflation begins when monthly inflation exceeds 50%.

- It ends when the inflation rate falls below 50% per month for at least one year.

To illustrate, if inflation drops to 40% in July and does not rise above 50% until July of the following year, then the period of hyperinflation is considered to have ended in July of the previous year. This definition allows for a precise characterization of hyperinflation episodes, enabling structured analysis.

This definition has been adopted in the Hanke-Krus table, which documents 56 episodes of hyperinflation. However, the table does not cover all episodes, such as the one in Venezuela in 2016, bringing the total to 57.

zoom

It should be noted that this definition, although precise, could possibly exclude

certain episodes of hyperinflation due to the strictness of the 50% threshold.

There is a possibility of expanding this definition to include other episodes

that, although not strictly meeting Cagan's criteria, nevertheless represent

periods of extremely high inflation. This observation opens the door to a broader

exploration of hyperinflation phenomena, allowing for a more nuanced understanding

of its causes and effects. In subsequent discussions, we will consider revisiting

this definition and examining episodes of hyperinflation not covered by Cagan's

strict criteria.

It should be noted that this definition, although precise, could possibly exclude

certain episodes of hyperinflation due to the strictness of the 50% threshold.

There is a possibility of expanding this definition to include other episodes

that, although not strictly meeting Cagan's criteria, nevertheless represent

periods of extremely high inflation. This observation opens the door to a broader

exploration of hyperinflation phenomena, allowing for a more nuanced understanding

of its causes and effects. In subsequent discussions, we will consider revisiting

this definition and examining episodes of hyperinflation not covered by Cagan's

strict criteria.

The Definition of Hyperinflation by Cagan

Philip Cagan may have set an arbitrary milestone with the 50% monthly inflation threshold when defining hyperinflation. He himself admits that this definition is arbitrary and primarily served his analysis based on seven episodes of hyperinflation. Examination of Cagan's data reveals that the three episodes of hyperinflation with the lowest monthly inflation rates were around 47%, 46%, and 57%. It appears that the 50% threshold was chosen to encompass these cases in his study.

Historical Context: Cagan's definition dates back to 1956 and is based on a limited number of hyperinflation episodes available at that time.

Cagan's Observations: According to Cagan, no episode reached this threshold of around 50% without progressing to a more severe hyperinflation, which could justify the choice of this threshold.

Critique of Cagan's Definition: Other economists, such as Bernholz, the author of Monetary Regime and Inflation, have also described the 50% threshold as arbitrary. Bernholz notes that there are episodes of high inflation with the same qualitative characteristics as episodes of hyperinflation, without reaching the 50% threshold.

This reflection leads us to question the rigidity of the traditional definition of hyperinflation and highlights the need to perhaps revisit this threshold by incorporating more episodes and historical data. The definition of hyperinflation may require flexibility to encompass various manifestations of extreme inflation in different economic and historical contexts.

The Definition of Hyperinflation According to the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB)

So, how many cases of hyperinflation are there in total? Common definitions of hyperinflation, such as the one put forward by Kagan stating a monthly inflation rate of 50%, can sometimes be confusing or oversimplified. For example, two countries experiencing respective annual inflation rates of 1,000% and 3,000% can be perceived differently depending on the monthly distribution of this inflation. If no month exceeds the threshold of 50%, according to Kagan's definition, these countries would not be in a state of hyperinflation. This approach can therefore lead to anomalies in the classification of hyperinflation, especially when comparing cumulative inflations over the year.

- Kagan's work, "Monetary Dynamics of Hyperinflation," which provides a fundamental analysis of hyperinflation.

- Bernold's book, which studies 30 distinct periods of hyperinflation, thus expanding the scope of analysis.

- David's personal collection of banknotes from 36 periods of hyperinflation, allowing for a tangible and historical understanding.

- The Hanky Cross table (2012 version, updated in 2016 with Venezuela), listing 57 periods of hyperinflation based on Kagan's definition.

It should be noted that certain historical periods of high inflation are not included in the classic tables of hyperinflation, often due to strict classification criteria. For example, during the American War of Independence in November 1779, and during the American Civil War in March 1864, the monthly inflation rates were 47.4% and 40% respectively. These rates, although high, do not exceed the 50% threshold stipulated by Kagan, thus excluding these periods from being classified as hyperinflation cases. This omission illustrates the limitations of rigid definitions and highlights the need for a more nuanced approach to understanding hyperinflation in all its complexity.

Weimar vs Zimbabwe similarities

Two eras, two catastrophes

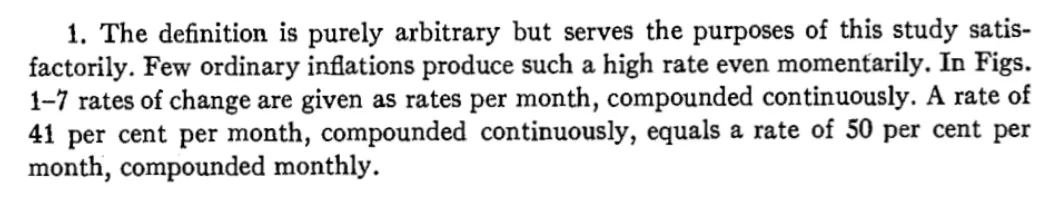

In this chapter, we will explore the impacts of hyperinflation, focusing on the cases of Zimbabwe and the Weimar Republic. Throughout my research, I have prioritized the exploration of direct testimonies from individuals who lived through these periods of hyperinflation, as opposed to a purely economic or statistical approach.

Several books have been particularly informative:

- "When Money Dies" by Adam Ferguson, traces the post-World War I hyperinflation in Germany, as well as in Austria and Hungary.

- Two books on hyperinflation in Zimbabwe, "Zimbabwe Warm Heart Ugly Face"

and "Hard Boiled Egg Index" by Jérôme Gardner and Kudzai Joseph Gou Min-Yu

respectively, offer poignant testimonies from a CEO of a clothing store

chain and an agricultural banker on their experiences during this

tumultuous period.

While consolidating my notes, I noticed numerous similarities between the experiences of hyperinflation in Zimbabwe and the Weimar Republic, despite the 90-year gap between them. I identified around 17 similarities, with 13 illustrating a sort of progression towards the economic disaster depicted in these testimonies. These fascinating parallels demonstrate the repetitive and devastating nature of hyperinflation across time and borders. Today, we will examine these similarities and how they depict a worrisome trajectory during periods of hyperinflation.

Comparative Analysis: Zimbabwe and the Weimar Republic

The game of 14 differences!

- Currency Shortage

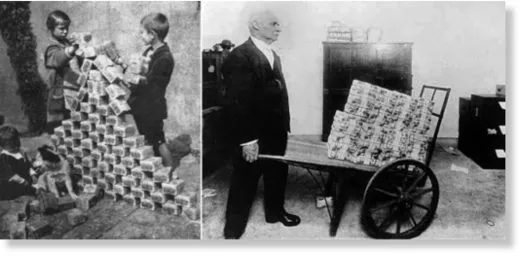

When currency depreciates at a dizzying speed, even the most ambitious attempts to flood the market with new banknotes can prove insufficient. The incessant demand for tangible currency can far surpass the central banks' capacity to produce banknotes, creating unprecedented liquidity crises.

Weimar: "During this month, it will be increased to almost 4 billion paper marks, a figure with which it is hoped that the currency shortage will be definitively overcome."

Zimbabwe: "From 2002 to January 2009, there were several critical liquidity shortages. There simply weren't enough banknotes printed or in circulation to keep up with the skyrocketing inflation."

- "And it's manure!"

The speed at which currency can lose its value in certain economic situations is astonishing. Astronomical amounts of banknotes can be issued in record time, instantly transforming once considerable sums into something as insignificant as manure.

Weimar: "The current total issue amounts to 63,000 billion. In a few days, we will therefore be able to issue two-thirds of the total circulation in one day."

Zimbabwe: "On September 17, 2006, the governor of the RBZ, Gideon Gono, declared: '10 trillion is still out there, and it has become manure.'"

- Banknotes worth less than the paper they are printed on In certain

economic circumstances, the intrinsic value of a banknote can become lower

than the value of the paper it is printed on. This drastic depreciation

turns banknotes, which are normally symbols of value and purchasing power,

into mere pieces of worthless paper.

Weimar: "Entire denominations of marks banknotes were almost worthless as soon as they came out of the printing press."

Zimbabwe: "The central bank wasted money by printing a banknote that was not worth the paper it was printed on. In other words, its value was lower than that of toilet paper. As absurd as it may sound, it was cheaper to use the ZWD 100 trillion banknote as toilet paper than to buy actual toilet paper."

- Money Counting

When currency rapidly loses its value, even the simplest transactions can become laborious tasks. Calculating the price of an item or simply counting the bills needed for payment can take several minutes, adding a layer of complexity to daily interactions.

Weimar: "The most ordinary purchase in a store required three or four minutes of calculation, and once the price was determined, several more minutes were usually needed to count the banknotes."

Zimbabwe: "Store managers were also allowed to hire a temporary worker to replace the staff member who counted money all day. Of course, counting money in-store for administration and bank deposit was one thing, but the whole process had to be repeated at the bank during the deposit."

Money counting technique from Uzbekistan

- Check Payments

In disrupted economies, traditional payment methods like checks can quickly lose their effectiveness. Banks, overwhelmed by the increasing demand for currency due to hyperinflation, may ration or delay the cashing of checks, thereby reducing their real value. This instability often leads to a prioritization of payment methods, where prices can vary depending on how one chooses to pay.

Weimar: "Price increases intensified the demand for money, both by the state and other employers. Private banks could not meet the demand at all and had to ration the cashing of checks, so uncashed checks remained frozen while their purchasing power dwindled." Zimbabwe: "The time value of money has created three prices for goods and services; namely, a cash price, a real-time gross settlement price, and a check price. Eventually, no one accepted checks, which took five days to clear." 6. The "Burner-preneurs"

As the value of the currency erodes, new economic opportunities emerge, exploiting market distortions. These entrepreneurs, often dubbed with inventive names like "Burner-preneurs," can thrive by borrowing devalued currency to invest in tangible assets, and then repaying their debts with even more devalued currency.

Weimar: "Speculation on inflation involved borrowing paper marks, converting them into goods and factories, and then repaying lenders with depreciated paper."

Zimbabwe: The "Burner-preneurs"

- Honesty and hard work lose their appeal

In unstable economic contexts, traditional values of hard work, thrift, and integrity can be overshadowed by the allure of quick wealth. Speculation and currency trading often offer much higher rewards than regular work, causing a disruption in societal priorities.

Weimar: "As the old virtues of thrift, honesty, and hard work lost their appeal, everyone sought to get rich quickly, especially since currency or stock speculation could apparently yield much more than work."

Zimbabwe: "These practices, while enriching a few individuals, impoverished the urban working class and the rural population. Education lost its value, as this trade was driven by people who did not need education or hard work to justify it. All they needed were connections and initial capital to start their easy money business."

- The "world banks"

In situations of hyperinflation or monetary crisis, parallel and unregulated markets for foreign currencies tend to proliferate. These informal "banks," often humorously referred to as "world banks" or by other local names, provide a refuge for those seeking to protect their assets from devaluation. Although these markets can provide a necessary economic lifeline, they often highlight widespread distrust of official financial institutions and government policies. Weimar: "Their transactions were mainly carried out through the so-called Winkelbankiers, the street operators who had emerged with inflation and who, thriving in a sick economy, lived entirely by taking advantage of the difference between the buying and selling prices of foreign currencies." Zimbabwe: "They were also currency changers. They operated with impunity between 2nd and 6th Avenue and Fort Street in Bulawayo, thanks to their cunning business skills involving corruption and other practices. This area of the city was known as the 'World Bank'." Argentina: "So I went where all Argentines go: the cuevas, the 'caves', which are found in the Florida neighborhood in the heart of Buenos Aires." - TheBigWhale

- Currency exchange was illegal

Governments, in an effort to stabilize their own currency and control the flow of capital, may make these foreign currency transactions illegal. These repressive measures, although intended to protect the national economy, can often have the opposite effect, exacerbating public mistrust and encouraging the black market.

Weimar: "People resorted to bartering and gradually turned to foreign currencies as the only reliable means of exchange. New decrees were introduced regarding the purchase of foreign drafts and the use of foreign currencies for domestic payments. In addition to imprisonment, fines could now be imposed up to ten times the amount of an illegal transaction."

Zimbabwe: "Raids on businesses led to the imprisonment of several businessmen from Bulawayo for the weekend and fines equivalent to twice the amount of recovered foreign currency, this bravery then subsided."

- Capital controls

When a country faces a monetary or economic crisis, one common response by governments is to exert strict control over the movement and forms of capital. Whether through orders forcing the acceptance of devalued national currencies or through severe sanctions against those who reject certain payment methods, these measures often aim to contain panic and restore confidence. However, their effectiveness varies, and sometimes these measures can prove counterproductive or disconnected from the reality experienced by citizens. Weimar: "Merchants had recently been forced by a new decree to accept state banknotes; but since it also allowed the continued use of foreign currencies for all purchases, merchants generally found excuses to accept almost nothing else."

Zimbabwe: "The government introduced SI 175/2008 on December 12, 2008, regarding payment by checks. It stated, 'The penalty for refusing payment by check/bank card or any other bank-mediated electronic payment method shall be a level 8 fine or a prison sentence of six months or both.' Obviously, we ignored the SI because it was completely out of touch with reality."

- Forced to keep their shops open

When the economy collapses and the currency loses its value, governments can resort to drastic measures to maintain an appearance of normalcy.

Weimar: "Merchants who continued their activities were subject to a new ordinance, enacted on October 22, requiring them to keep their shops open and offer goods in exchange for paper marks."

Zimbabwe: "Only empty steel shelves and refrigerators, coolers, and freezers remained. The tragedy was that the store was still open because they dared not close due to political tensions and the fear of leaders being arrested by the government's price control force. Even the workers were not laid off because everyone thought there would be a quick solution."

- Everyone is a criminal

In the face of a collapsing economy and pervasive regulations, the line between survival and criminality becomes blurred.

Weimar: "All crimes against the state, each and every one of them, to varying degrees, became a matter of survival for individuals."

Zimbabwe: "Every resident in Zimbabwe was a criminal. Harsh as it may sound, it was true. With the myriad of small laws governing every aspect of life, it was inevitable that everyone would break a law every day. Owning foreign currency was illegal, according to an SI published in 2004. Having multiple bank accounts to bypass the daily withdrawal limit was illegal. Not having the correct license plates on your car, or no car radio license or generator permit, were all laws that someone, somewhere, was breaking." 13. Buying foreign currencies at any price The frantic purchase of foreign currencies has often marked a critical turning point in currency devaluation, exacerbating the fall in intrinsic value.

Weimar: "Mannheimer, on the instructions of his boss, went out in August 1921 and started buying foreign currencies at any price - 'because Germany had an infinite amount of paper marks but no foreign currencies.' This was the first sign of the absolute collapse in the value of the mark."

Zimbabwe: It has been alleged that they were given daily targets to meet, as some of the forex requirements were urgent and they would buy at any rate to accumulate forex to meet the deadline. This alleged practice was accused of fueling the fire of devaluation as the value of the Zimbabwean dollar continued its steep decline."

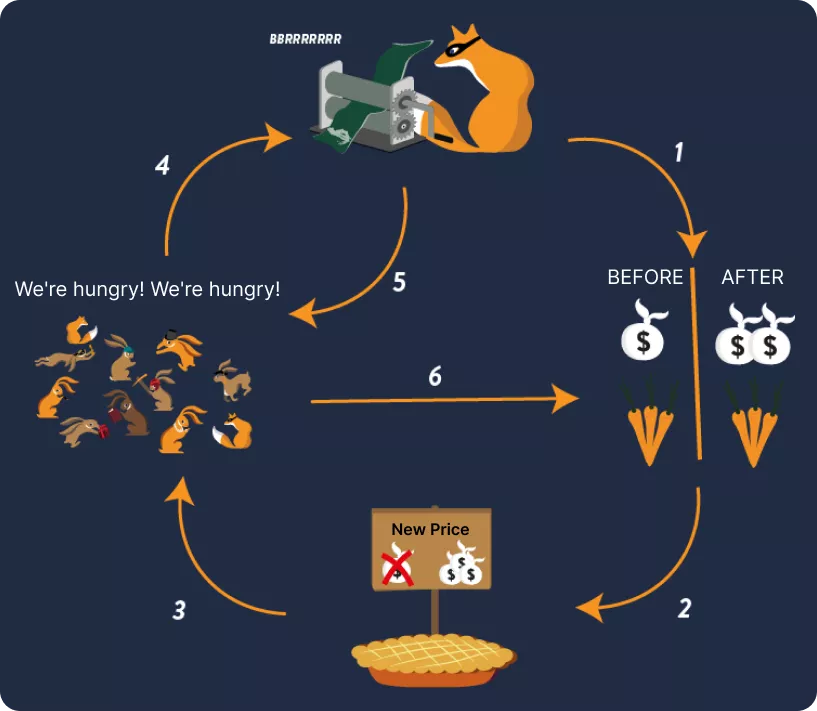

Summary of the process

When analyzing the economic trajectory, it is apparent that when high inflation is reached, the value of the monetary mass deteriorates. This devaluation leads to several complications, including a shortage of banknotes. In this context, arbitrage opportunities arise, especially with exchange rate fluctuations. As a result, many individuals turn to this arbitrage, investing heavily in tangible assets in anticipation of future currency devaluation that would allow them to repay their debts with a weakened currency. This economic environment undermines the appeal of traditional jobs and, consequently, erodes social cohesion.

In response to this situation, the government imposes draconian regulations, including capital controls. It also mandates that merchants accept the national currency and checks. Over time, new laws are enacted, expanding the definition of criminal behavior. Ultimately, the exchange rate climbs exponentially as the government is willing to exchange its currency, printed at a lower cost, for more robust foreign currencies.

4 Similarities in the consequences of hyperinflation

- Oil and metals

In Germany during the Weimar period, the theft of precious materials was such that lead from roofs was frequently stolen. In Zimbabwe, desperation led some to interrupt the power grid to extract oil from transformers and use it in their vehicles. In the context of a deteriorating economy and scarcity of resources, governments may implement rationing systems to control the distribution of essential goods. This includes the use of coupons or vouchers to regulate the purchase of gasoline or fuel.

Weimar: "In Berlin, due to the scarcity of gasoline, a coupon system was implemented to regulate its distribution. Each citizen was assigned a specific amount of coupons that allowed them to purchase a limited quantity of fuel."

Zimbabwe: "During the fuel crisis, the government introduced a coupon system to manage the distribution of gasoline. Each individual was given a set number of coupons that could be exchanged for a certain amount of fuel." The populations are looking for stable alternatives for transactions. In Weimar, products such as brass and fuel served as means of exchange due to their constant intrinsic value. In Zimbabwe, facing the rapid devaluation of the Zimbabwean dollar, gasoline coupons, which represented a fixed quantity of an essential product, became a de facto currency. These situations highlight how societies adapt to extreme economic conditions, finding innovative solutions to keep trade and the economy moving.

Weimar: "Bartering was already a common form of exchange; but now, goods like brass and fuel became the common currency for purchase and payment."

Zimbabwe: "We now used these vouchers to pay rent to landlords, municipal taxes, phone bills, in fact, almost everything, as everyone had stopped accepting payments in Zimbabwean dollars and checks."

Conclusion

This concludes this video on the similarities of the experiences during the periods of hyperinflation in Zimbabwe and the Weimar Republic. In the next video, we will discuss the differences and contemporary parallels. Thank you.

Weimar vs Zimbabwe: Differences and Contemporary Parallels

In this chapter, we will explore the differences and contemporary parallels between past and present hyperinflation periods, with anecdotes and relevant comparisons for today.

Differences between the Weimar Republic and Zimbabwe

- It's the dollar's fault!

In Germany, it was common for the population to attribute inflation to the rise of the dollar rather than the intrinsic devaluation of their own currency. Many believed that the observed phenomenon was due to an appreciation of the dollar. This perception dismissed any recognition of the link between their economic difficulty and monetary devaluation, mainly induced by excessive money creation. The book "When Money Dies" clearly illustrates this lack of understanding among the German population. In contrast, in Zimbabwe, the situation was different: citizens were fully aware of the underlying cause of the hyperinflation they were experiencing.

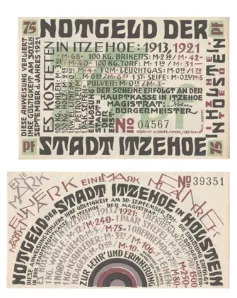

- Necessity currency (Notgeld)

Facing the monetary and economic crisis, Germany resorted to "Notgeld"

(emergency money). These notes, printed by cities or certain companies, were

designed to address a shortage of common currency. Interestingly, France

also resorted to Notgeld, particularly in the 1920s. This initiative was not

only a direct consequence of hyperinflation but also had roots in the

disruptions caused by World War I. The war not only destabilized the economy

but also increased the cost of metals. As a result, the intrinsic value of

metal coins often exceeded their face value, prompting people to hoard them.

In the absence of coins, some institutions, such as the Lyon Chamber of

Commerce, printed their own Notgeld.

"What has to be done, has to be done." - a local saying

Among the Notgeld, one particular banknote stands out. It features a poignant illustration: in the center, an individual is depicted defecating a Mark. On the reverse side, a price table from 1913 to 1921 illustrates the rise of inflation during this period.

The artist behind this Notgeld seems to be making an ironic critique of the authorities responsible for the hyperinflation crisis. The banknote bears the inscription "Necessity knows no law". Another expression specific to the locality of origin of the Notgeld states: "What has to be done, has to be done".

"necessity knows no law"

The first Shitcoin: Anecdotally, looking at the central illustration of the banknote, where the currency is literally devalued by the individual's action, it could be called the first "shitcoin".

- Debentures and Mortgages

In Weimar, some debts were revalued to compensate for the impact of inflation. This measure was not adopted in Zimbabwe.

Weimar: "A decision to revalue government-owned loans became law in 1925, resulting in shareholders receiving 2.5 percent of their initial investment provided that all reparations had been paid."

Zimbabwe: "In July 2007 (three years later), I could take out a devalued ZDW 500,000 (bt "000") note from my pocket, now worth $1.67 at the parallel market rate, and repay the mortgage loan, which was supposed to be repaid over twenty years. Furthermore, this note represented only 0.49 percent of my monthly salary for the same month."

To learn more about the management of the German crisis, this book is also essential.

Contemporary Parallels

- Manipulation of monetary policy to control the economy. In the history of the Weimar Republic, it is evident that industrialists were reluctant to see the appreciation of the Mark. Their ability to borrow and repay their debts with a heavily depreciated currency gave them a considerable advantage. This mechanism facilitated the construction of huge industrial complexes at almost no cost. These industrialists feared an appreciation of the Mark as it hindered their activities. Some even saw rampant inflation as a good thing, believing it guaranteed employment for the population. However, they did not realize the detrimental impact of this inflation on savings and the economy in general. For these economic actors, monetary printing was a blessing.

Weimar: "This is why an appreciation of the mark was greatly feared, and even the few weeks of 'stability' after Genoa caused a stagnation of business."

Weimar: "Industrial circles faced the danger that cash would become more valuable than goods, and a collapse would occur when everyone tried to convert their assets into cash."

A contemporary parallel can be drawn with Christine Lagarde's statements, suggesting that citizens should prioritize the prospect of employment over the protection of their savings. Just like the industrialists of Weimar, she seems to advocate for monetary printing as a tool to stimulate employment, at the expense of the value of savings.

Christine Lagarde: "We should be happier to have a job than to see our savings protected."

- Private property in times of conflict.

The history of the Weimar Republic reveals that during this period, assets and capital held abroad were confiscated. This measure recalls more recent events in Russia, especially at the beginning of a conflict. These situations highlight a concerning reality: in times of crisis, respect for private property can be compromised. This is a historical and contemporary parallel that underscores the potential repercussions of crises on individual rights.

Weimar: "All German capital held abroad had been confiscated."

20minutes.fr: "Approximately

300 billion of Russian reserves held abroad have indeed been frozen as part of Western sanctions, out of the640 billion in reserves held by the Russian Central Bank."

- The concept of market prices.

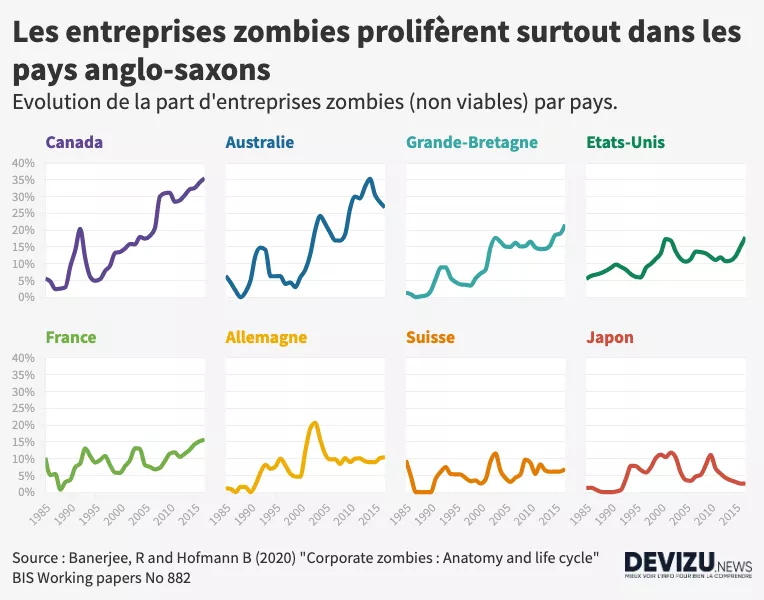

Weimar : "Les entreprises zombies"

Contemporary: "Les entreprises zombies" Weimar: "Stabilization put an end to the period when entrepreneurs could borrow as much as they wanted at the expense of everyone else. A large number of companies, created or developed during the monetary abundance, quickly became unproductive when capital became scarce." A zombie company is a company that, under normal market conditions, would be insolvent or close to bankruptcy, but continues to operate mainly through low-cost borrowing. These companies earn just enough money to cover their debts but are unable to grow significantly.

The concept of zombie companies is not new. In fact, it was present in the Weimar Republic. At that time, many companies appeared to be flourishing, benefiting greatly from access to free credit. They borrowed considerable sums, with the prospect of repaying later with a depreciated currency due to rampant inflation. However, when inflation stopped and the German mark regained value, these companies, which were not truly viable in operational and financial terms, became unprofitable and had to close their doors.

The phenomenon of zombie companies is not limited to the post-war history of Germany. Even today, many large companies survive thanks to privileged access to very low-interest credit. If they had to borrow at more conventional rates, many of them would cease to be profitable. This is particularly relevant as we are in 2023, and after a long period of near-zero interest rates, they have started to rise. This recent development in the financial landscape will undoubtedly be a decisive test for these companies that were once called "zombies".

- Get rich quick!

Throughout history, there have been moments when individuals seek to get rich quickly, as was the case in Weimar and Zimbabwe through arbitrage. Today, we see a similar trend with the emergence of certain cryptocurrencies. People are tempted by quick gains, taking risks in the hope of exponential multiplication of their investment. This approach can be reminiscent of what is observed during periods of hyperinflation, where arbitrage is used to obtain quick gains, often at the expense of others.

- Savings, the remedy against uncertainty

the invasive and destructive influence of the constant erosion of the value of capital and income, as well as uncertainty about the future. It is interesting to highlight a quote that emphasizes the destructive effect of the erosion of the value of capital on social cohesion, as well as the uncertainty it generates. It says: "the invasive and destructive influence of the constant erosion of the value of capital and income, as well as uncertainty about the future."

Imagine a scenario where you have a family or loved ones that you want to protect. You work hard, save money, to anticipate future uncertainties. If everything was predictable, saving would be useless. But in the face of the unexpected, like a broken-down car, savings become a lifeline. It reduces the uncertainty of the world. However, in a period of hyperinflation, saving becomes a challenge. Money quickly loses its value, making long-term planning difficult. This financial instability can cause stress and anxiety.

Today, in the face of declining purchasing power, investment takes over. However, this approach comes with its own risks. Savings have always been a remedy against uncertainty. Having financial reserves to manage unforeseen situations contributes to peace of mind and strengthens social cohesion. In conclusion, protecting our purchasing power is essential to maintain social and individual stability.

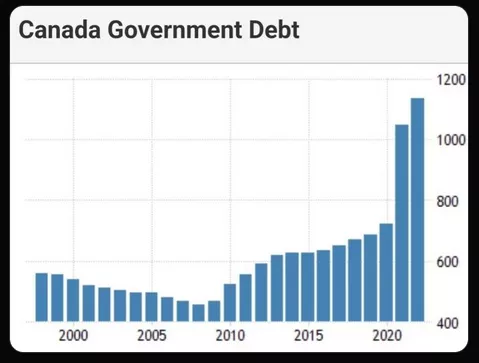

Redenominations in Latin America

We will now look at different periods of redenomination in Latin American countries.

Explanation of the graphs

On the slide, on the left, are the years of redenomination, the name of the new currency, and the exchange rate with the old currency. Taking the example of Argentina, the peso moneda nacional was converted at a rate of 25 to 1 from the previous currency, the peso real. In this context, we will examine the evolution of the Argentine currency over time. Additionally, we will indicate the initial and final denominations of banknotes for each period.

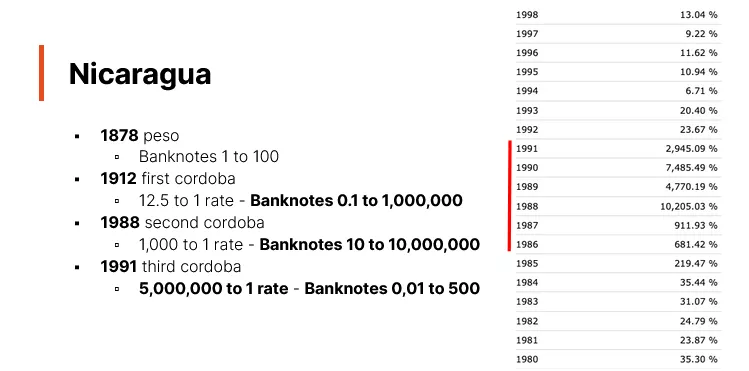

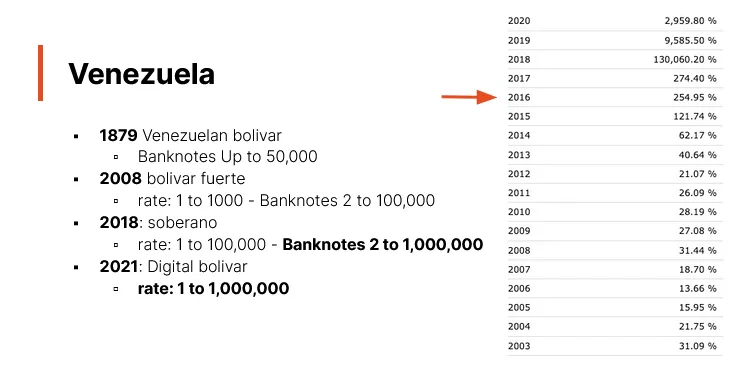

On the right side of the slide, there is a graph of inflation. The red arrows represent years of hyperinflation, defined according to Kagan's criterion as an inflation rate of 50% per month. This criterion can sometimes lead to ambiguous interpretations, with years having high inflation rates but not meeting the strict definition of hyperinflation. It should be noted that redenomination, during periods of inflation, is a common measure taken by governments. However, this does not solve the underlying problem of inflation or hyperinflation. It is only a way to rename the currency and remove zeros, without truly addressing the root cause of hyperinflation: the expansion of the money supply. In a later video, we will discuss the real solutions to address and resolve the problem of hyperinflation. In this series, we will highlight the consequences of a simple redenomination without adequate reforms: inflation persists. After Argentina, our study will cover Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. We will examine the redenominations that have taken place in these countries.

Argentina

Before 1826, Argentina used the Spanish dollar. After its independence in 1816, it introduced its own currency based on the Spanish real, resulting in the creation of a similar currency. The table starts in 1881, the year of the introduction of the "peso moneda nacional" with banknotes up to 10,000. This was followed by the "peso ley," exchanged at a rate of 100 to 1 and with banknotes up to one million. Then, the "argentine peso" arrived with an exchange rate of 10,000 to 1 (equivalent to removing four zeros), and banknotes up to 10,000. In 1985, the "australes" was introduced and exchanged at 1,000 to 1, with banknotes up to 500,000. In 1992, the current "peso ley" was established at a rate of 10,000 to 1, once again removing four zeros. Only the years 1989 and 1990 experienced hyperinflation.

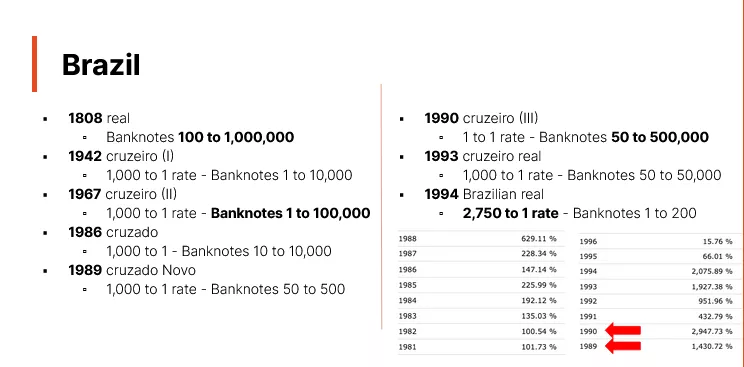

Brazil

Brazil is an emblematic case of monetary redenomination, as illustrated by its history of currency changes. Before its independence, Brazil used the Portuguese real. However, as early as 1747, the country began using its own "Brazilian real," long before its declaration of independence in 1822. The table starts in 1818, marking the beginning of the issuance of Brazilian banknotes. Before that, the currency was mainly in the form of coins. These banknotes reached values of up to one million reals. Starting from 1942, Brazil began a series of redenominations. In most cases (1942, 1967, 1986, 1989, 1993), the conversion rate was 1,000 to 1. In 1990, a name change without conversion took place. The sequence of these currencies is as follows:

- Réals (old version) until 1942.

- Cruzeiros in 1942.

- Cruzeiros (new version) in 1967.

- Cruzados in 1986.

- Cruzados Novo in 1989.

- Return to Cruzeiros in 1990.

- Cruzeiros Reais in 1993.

- Finally, the Brazilian Real in 1994.

The highest denomination bill reached 500,000, and the last redenomination in 1994 was done at a rate of 2,750 to 1. The years 1989 and 1990 were marked by hyperinflation, while 1993-1994 saw high inflation rates without reaching the threshold of hyperinflation (50% per month). After this tumultuous period, Brazil once again redenominated its currency by removing several zeros.

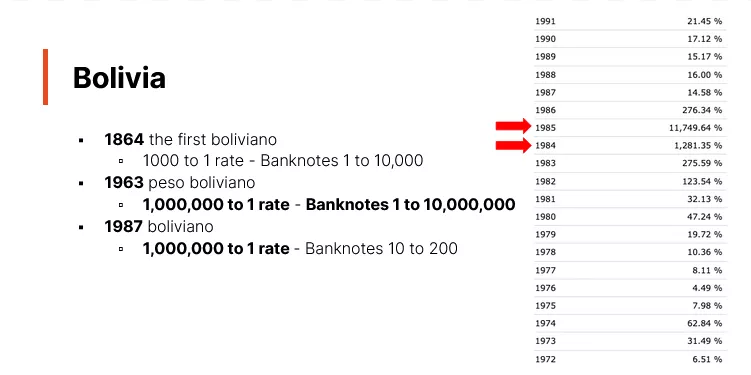

Bolivia

Bolivia is another example of a country that has gone through periods of acute inflation, requiring currency redenominations. Here is a summary of its monetary history:

Before its independence in 1825, Bolivia used the Spanish dollar as its currency. After independence, the country introduced the Bolivian Sol between 1827 and 1864, replacing the Spanish dollar. However, it should be noted that the first banknotes in Bolivia only appeared in 1864.

In 1864, the first "Boliviano" was introduced, with an exchange rate of 1,000 to 1 compared to the Bolivian Sol. This currency remained in circulation until it reached a denomination of 10,000 Bolivianos. Subsequently, Bolivia changed its currency to the "Bolivian Peso," which experienced such severe hyperinflation that it eventually reached denominations of up to 10 million. This episode of inflation peaked in the years 1984-1985, with monthly inflation rates often approaching the hyperinflation threshold of 50%. To provide some perspective, a constant inflation rate of 50% per month over a full year results in an annual inflation rate of approximately 12,800%. In 1985, Bolivia's annual inflation rate reached 11,749%, indicating that almost every month, inflation was close to or exceeded the 50% threshold.

In response to this monetary crisis, in 1987, Bolivia introduced a new currency, simply called the "Boliviano," with an exchange rate of 1 million Bolivian Pesos for 1 Boliviano. This version of the Boliviano is still in circulation today.

That is an overview of Bolivia's tumultuous monetary history, marked by periods of hyperinflation and redenominations.

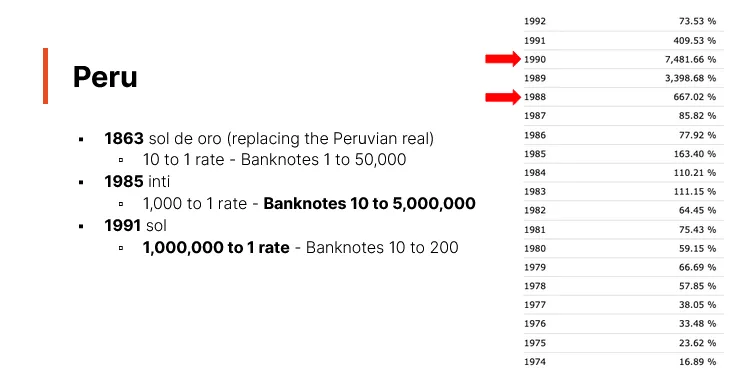

Peru