name: Introduction to Austrian Economics goal: Discover the Austrian school of economic thought. Study their views on society and macro/micro-economic realities. objectives:

- An alternative to Keynesianism

- The importance of hard currency

- Why and how are our economic cycles created?

- Why have central bankers gone mad?

A Journey into Economics

Welcome to Théo Mogenet's course! Passionate about economics, history, literature, political science, and technology, he has decided to share his knowledge of Austrian economics with you. This branch, less known in economics, is based on human rationality and free actor behavior. Less intense in mathematics, it is a question of logic and social study above all.

This school of thought has already had several centuries behind it and has a whole panorama of authors, thoughts, and economists behind it. Great names in economics such as Hayek, Rothbard, Mises, Bastiat, or Menger have long defended this movement. In contrast to the omnipresent Keynesianism of our day, the Austrian school puts the individual back at the center of the equation with a more liberal, capitalist, and even anarchist approach.

Introduction

Course Overview

Welcome to the ECO201 course!

In this course offered by Théo Mogenet, you will discover a school of economic thought that fundamentally differs from the prevailing Keynesian doctrine. So far, you may have been taught that money management and economic policy are primarily the domain of central banks, with the idea that monetary printing and public spending stimulate economic growth. However, there exists a more coherent alternative approach: Austrian Economics.

With over two centuries of research, philosophical reflection, and writings by renowned authors such as Carl Menger, Ludwig von Mises, and Friedrich Hayek, this school of thought takes a different perspective, favoring a decentralized view of the economy based on the individual and human rationality.

Economics is, in reality, a deeply social and complex field, composed of numerous independent actors who interact freely to form a coherent whole. To understand this dynamic system, Austrian Economics favors qualitative analysis, based on human logic, sociology, and the study of market processes, rather than rigid mathematical equations.

In this course, you will explore the fundamental principles of this school of thought. Théo Mogenet, your instructor, is a passionate advocate of this economic approach and will guide you through the key concepts of Austrian Economics, showing you how these ideas particularly apply to the world of Bitcoin.

Section 1: Introduction to ECON

We will begin with a general introduction to Austrian Economics, exploring its

historical origins and the foundations of its thought. This section also covers

essential concepts such as money, credit, banks, and central banks. You will

understand why these institutions play a central role in Austrian thought, particularly

in their criticism of monetary interventions.

Section 2: Theoretical Foundations

This section will delve into the fundamental concepts of Austrian Economics,

such as the subjective theory of value, which explains why the value of a good

is not objective but depends on the perceived utility by each individual. You

will also discover how money naturally emerges as a social phenomenon, along

with the concepts of time preference, interest, and capital that are at the heart

of the Austrian free-market theory.

Section 3: Austrian Economic Perspectives

Here, we will explore the practical applications of Austrian theory. You will

learn in detail about the Austrian Business Cycle Theory, which explains how

monetary manipulations create artificial booms followed by recessions. We will

also see why economic calculation is impossible under a socialist system and

how the Austrian methodology, based on praxeology (the study of human action),

provides a unique and coherent approach to understanding economic phenomena.

This course is a blend of economics and philosophy, led by an open discussion between Théo and me (Rogzy). I would like to warmly thank Théo Mogenet for creating this course. We greatly enjoyed developing this content, which is designed to be accessible to everyone. This course serves as an essential introduction and will lay the groundwork for our future, more advanced economic modules.

And what if the key to understanding today's economy lies in a theory several centuries old? Let's discover it together!

Money, Credit, Banks, and Central Banks

“The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust. Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve. We have to trust them with our privacy, trust them not to let identity thieves drain our accounts.”

Satoshi Nakamoto, pseudonymous inventor of Bitcoin

How Money is Created

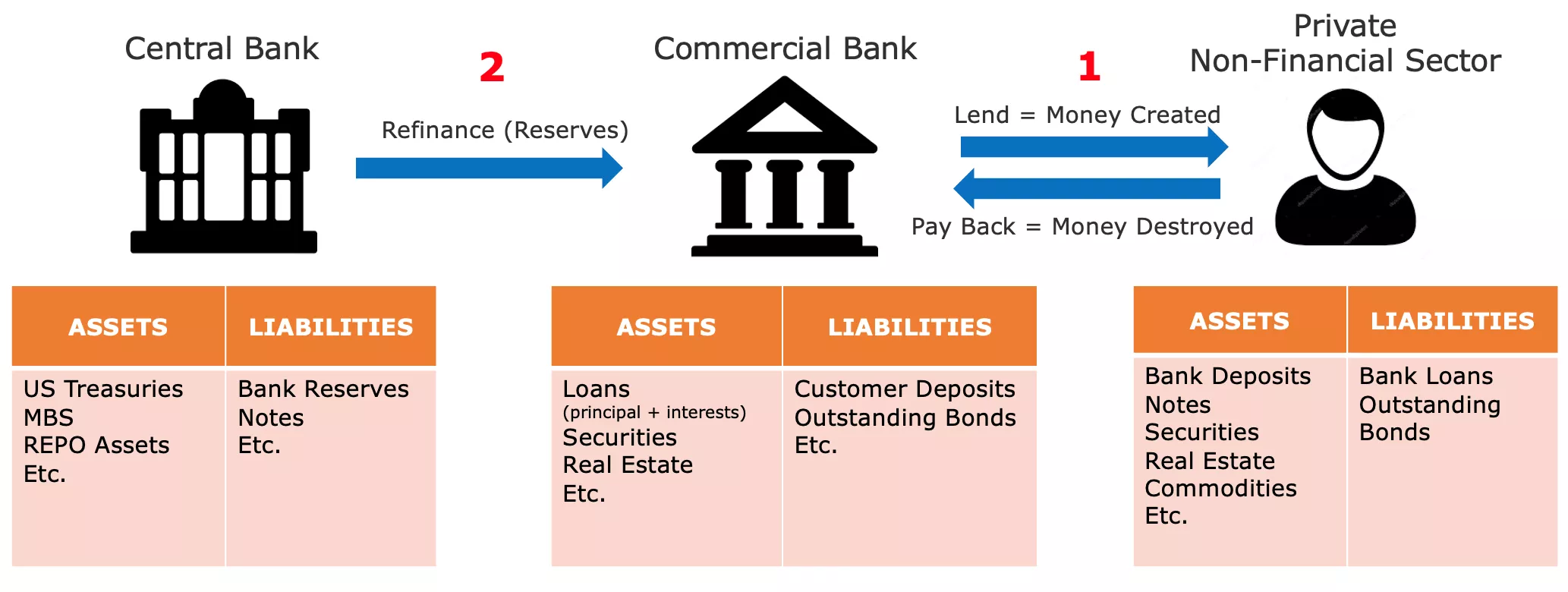

In our present-day monetary system, money is primarily created through a banking practice known as "fractional reserve banking." This term essentially means that banks are not required to hold as many reserves as they receive in deposits. Consequently, they can create new purchasing power when granting loans and, conversely, reduce purchasing power when customers repay their loans.

For example, if you were to approach your local bank to secure a mortgage for a house purchase, the money lent to you by the bank would come into existence as a bookkeeping entry. In accounting, we typically represent an individual's net wealth with a balance sheet, which has two sides: the asset side, including any property, financial contracts, inventory, or other forms of wealth owned, and the liability side, showing the source of funds used to create the capital listed on the asset side. The difference between assets and liabilities is referred to as "equity" and can be thought of as the net wealth of the entity.

When a financial institution holds a banking license, it essentially means that the liabilities recorded as "customer deposits" are considered official money within a specific country or monetary zone. Therefore, when you seek a loan to purchase a house from the bank, the banker doesn't lend funds deposited by another customer. Instead, the bank credits the borrowed amount to your account and simultaneously records your loan contract as an asset of the bank. As you repay your loan, money is effectively extinguished, and the value of the corresponding loan contract decreases, with the bank retaining only the interest on the loan.

Upon purchasing the house, you instruct your banker to transfer money to the seller's account. If the seller's account is with a different bank, your banker notifies the corresponding banker at the other institution to ensure the seller's account is credited accordingly, while debiting your account by the corresponding amount.

Figure 1: Money Creation as Bookkeeping Entries

“It is well enough that people of our nation do not understand our banking and monetary system, for if they did, I believe there would be a revolution before tomorrow morning”

Henry Ford

This process allows banks to record all transactions, including wire transfers, credit card purchases, and checks, over a specified period (usually a week or a month). They then settle these transactions with each other using bank reserves, which are another form of fiat currency never used by the public. Bank reserves are held at the central bank in a special account accessible only to licensed banks and financial institutions.

Instability of Fractional Reserve Banking and Lender of Last Resort

The main issue with this fractional reserve system is that significant withdrawals from a particular bank can potentially lead to its bankruptcy. Since banks must meet customer demands for cash while holding only a limited buffer of bank reserves, a simultaneous rush by many customers to withdraw funds can render the bank unable to satisfy these demands, resulting in bankruptcy. Given that many individuals, firms, and institutions have their funds deposited in banks, allowing a bank to fail could have severe economic consequences, such as a recession or even a depression.

This conundrum gave rise to the modern central banks. In the 19th century in England, repeated bank runs threatened financial stability, leading to the establishment of the Bank of England as the “lender of last resort.” The Bank of England was tasked with lending funds to distressed banks during crises to prevent a domino effect that could paralyze the entire financial system. This concept of central banks as lenders of last resort has since spread worldwide and become commonplace.

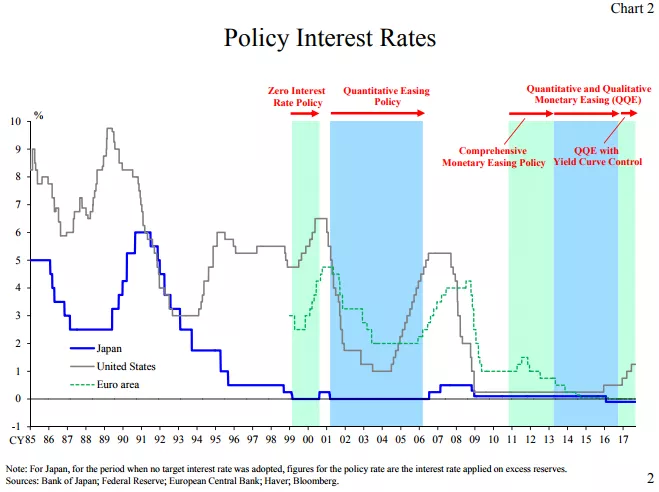

In addition to maintaining financial stability, central banks are responsible for setting key policy rates. These rates determine the cost at which licensed banks can borrow funds from the central bank, essentially defining the cost of liquidity for the financial institutions that play a crucial role in lending in our economies. Therefore, these rates serve as a benchmark for the entire financial system. As an individual, the interest rates you pay on your mortgage can be broken down into the policy rate and the bank’s margin.

Figure2: Lehman Brothers’ Bankruptcy (15/09/2008)

During the major financial crisis of 2008, Lehman Brothers, a large investment bank, declared bankruptcy after suffering significant losses on its mortgage securities holdings and experiencing massive withdrawals from concerned clients. In response to this unprecedented financial turmoil, central bankers around the world injected large amounts of liquidity into financial markets, merged struggling investment banks with commercial banks, and lowered policy rates to near zero in an effort to prevent a systemic collapse.

While these measures prevented a cascading wave of bankruptcies, they did little to alleviate the subsequent economic slowdown. Millions lost their jobs and homes, consumer spending plummeted, businesses went under, and banks incurred substantial losses. Despite historically low interest rates, few were willing to borrow, resulting in a vicious cycle where the initial decrease in spending and investment reinforced itself. Consequently, central bankers took further steps by implementing Quantitative Easing (QE) programs. These programs involved central banks purchasing government bonds and mortgage-backed securities from commercial banks with central bank reserves.

Figure3 : Interest Rates Across Major Economies / Source: ECB

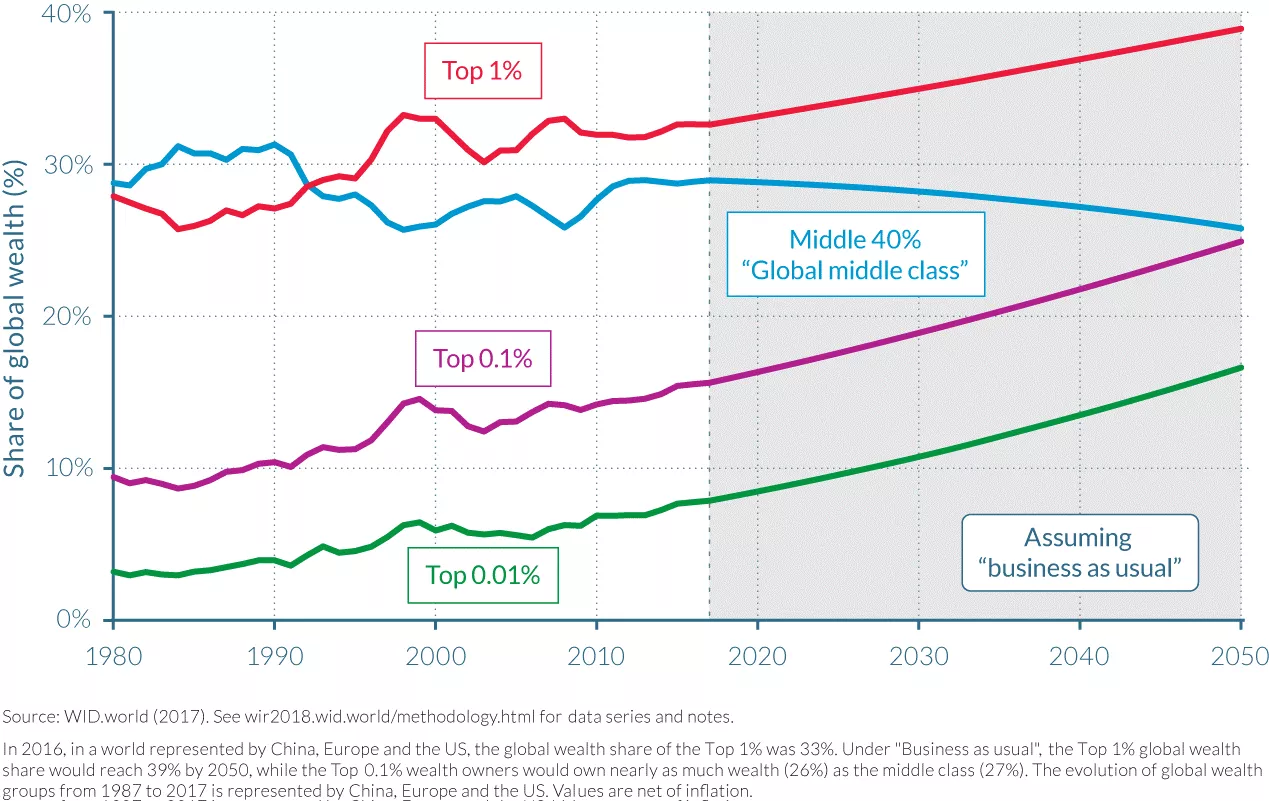

Contrary to many expectations, QE programs did not significantly revive economic growth but did inflate financial assets to historic levels. This primarily benefited the wealthy and financial institutions, as they already held substantial quantities of such assets, thereby widening wealth disparities. Given the structure of the banking system explained earlier, this outcome should not come as a surprise. Since bank reserves cannot easily flow into the real economy, QE programs mainly boosted asset prices without effectively improving the financial situations of average individuals.

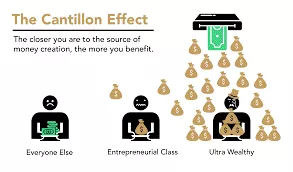

The Cantillon Effect

Nonetheless, an essential economic principle can be drawn from this episode: when new money is created, it initially benefits those closest to the source of the money, at the expense of those further away. This economic insight dates back to the 18th century when Richard Cantillon outlined it in his "Essay on the Nature of Commerce in General." It is now colloquially referred as the “Cantillon Effect”.

Figure4: Cantillon Effect in a Nutshell / Source: River Financial

In this instance, bankers, bank executives, stock and bond owners, real estate developers, real estate lenders, and anyone holding financial assets or real estate received a financial windfall, while the burden fell on everyone else. This situation persisted for years and largely explains the growing wealth inequality, the sense of disenfranchisement among hardworking individuals, and the seemingly unstoppable rise in asset prices despite sluggish GDP growth.

In essence, the system is skewed. Banks are inherently unstable, yet their failure can jeopardize the entire economy. This moral hazard incentivizes bank executives to take excessive risks to maximize their bank's revenue, knowing that the central bank will ultimately bail them out, shifting the cost to taxpayers. In such scenarios, central bankers create conditions for a massive transfer of purchasing power from hardworking individuals and savers to asset owners and those connected to the financial system, thereby disconnecting the process of wealth creation from wealth accumulation.

Figure5: Wealth Distribution in China + Europe + the US / Source: OECD

Consequences of Zero Interest Rate Policies

During extended periods of Zero Interest Rate Policies (ZIRP), banks have limited opportunities to rebuild their equity because their margins are eroded. Banks typically earn money by borrowing at short-term rates and lending at longer-term rates. However, when central banks purchase large quantities of bonds and set rates at zero, banks have little incentive to lend, especially to entrepreneurs and other risk-takers. Instead, they allocate their resources to securitize existing capital or provide loans against collateral to meet the demand of those benefiting from the Cantillon effect.

Another unintended consequence of ZIRP is that it encourages governments to engage in extensive spending. Since governments face no borrowing costs and can rely on central banks to purchase their bonds through QE programs, they have a natural incentive to spend as much as possible, particularly in democratic contexts where spending can garner votes. This tendency often disregards the long-term consequences of such fiscal profligacy, leading to a significant increase in public debt levels across developed economies since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

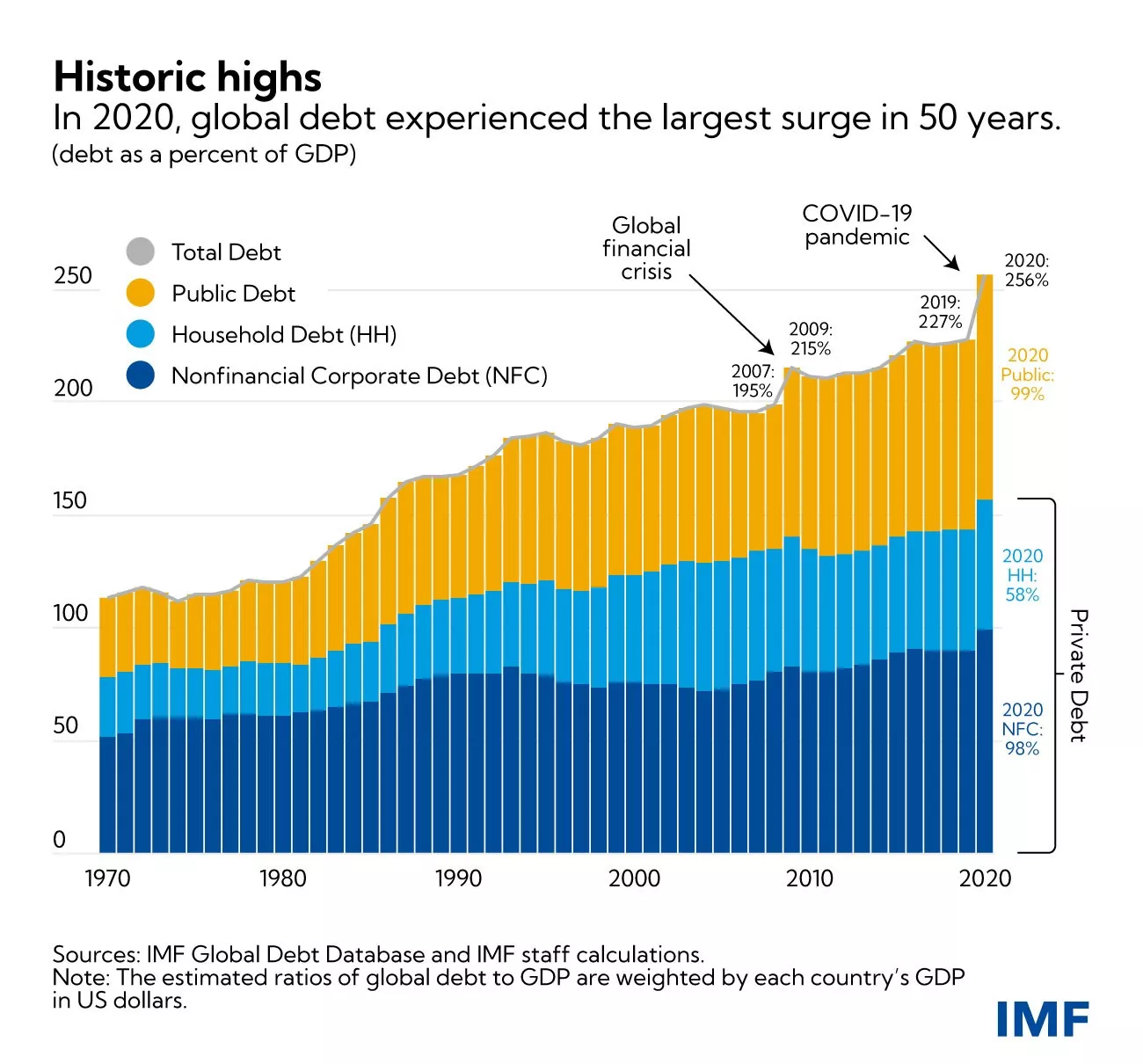

Figure 6: Public & Private Debt as % of GDP (World, weighted by GDP per country) / Source IMF

With inflation on the rise due to substantial money creation in response to COVID-related lockdowns, central bankers are now raising policy rates in an attempt to curb inflation. However, this poses a significant challenge for the entire system. Banks are more leveraged than ever, governments carry historically high levels of debt, economic growth is sluggish, deficits are mounting, and consumers, grappling with rising prices for essential goods, are struggling to make ends meet. Controlling inflation would require raising rates to a level that could bankrupt governments, while banks risk losing depositors as individuals spend their savings on increasingly expensive essentials or seek refuge in hard assets and money market funds to hedge against inflation.

Conclusion

“By this means (fractional reserve banking), governments may secretly and unobserved, confiscate the wealth of the people, and not man in a million would detect the theft”

John Maynard Keynes

In essence, our system is facing substantial challenges, and Bitcoin emerges as the only credible alternative. However, Bitcoin alone cannot address the issues within our monetary system. Above all, we need individuals who understand basic economic principles among Bitcoin enthusiasts, enabling a broader awareness and economic common sense to guide us away from constructing another fragile financial foundation for our civilization. The primary objective of this course is to educate new Bitcoin enthusiasts in sound economic principles.

To achieve this goal, we will explain the fundamental principles of "Austrian Economics," an economic school of thought with a methodological tradition dating back to the 16th century, providing insights into human action under economic constraints. With this introduction, you now grasp the essentials of money creation and the current state of our financial and monetary system.

In the upcoming chapter, we will delve into the foundational cornerstone of any economic school of thought: the theory of value. Subsequent chapters will explore money as a social institution, the theory of capital and the business cycle, the challenge of economic calculation, and a brief overview of the history and methodology of the Austrian School of Economics.

Theoretical Foundations

The Subjective Theory of Value

“Value only exists within human consciousness”

Carl Menger, Principles of Political Economy

The Marginal Revolution

At the root of economic reasoning lies the question of value. How do we determine the value of something? Is value an inherent property of things? Or is it, on the contrary, a subjective phenomenon? How do we compare the value of two things? Where does value come from?

Such questions have occupied economists and philosophers for many centuries and have received numerous different answers. In many ways, the epistemological evolution of economics has been punctuated by the evolution of theories of value.

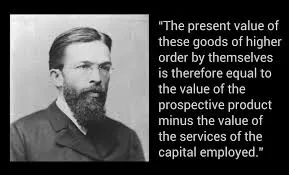

After the physiocrats' theory of land value, positing that all value come from land, had been refuted by the classical economists' labor theory of value, postulating that the value of a good stems from the amount of labor going into its production, it was the turn of the marginal theory of value to supplant the latter. In the 1870s, following Marx, the last of the classical economists, three new schools of economic thought emerged almost simultaneously around a marginal theory of value: the Lausanne school with Léon Walras, the modern or neoclassical school with William Stanley Jevons, and the Austrian school with Carl Menger. This revolution in the theory of value constituted a significant renewal of economic thought.

From Left to Right: William Stanley Jevons, Carl Menger, Léon Walras

The marginal theory of value holds that economic value corresponds to what an economic agent willingly pays for the next unit of a good or service. As this theory emphasizes the fact that prices are formed at the margin, i.e. for the next unit of a given good, it was termed “marginalism”.

It is common to present the marginalism of these three schools as similar. Indeed, Walras and Jevons are highly compatible, but Menger’s theorization diverges from the others in profound ways. In his work, now considered foundational to Austrian economic theory, titled "Grundsätze des Volkswirtschaftlehre" (Principles of Political Economy), published in 1874, Menger, offers a marginal, but primarily subjective, explanation of value, unlike Walras and Jevons, who consider value to be an objective and measurable phenomenon.

Subjective Value

The Austrian economist refutes the conception of Adam Smith's successors and abandons the idea that the value of a good comes from the amount of labor used in its production, in favor of the notion that its value is determined by the individual, who, in each context, performs a mental act of valuation regarding a specific quantity of a good or service. This intellectual leap made by Menger challenges the objectivity of value: for him, value is not an objective property of goods; it is merely the result of the relationship that the individual has with that thing: "value does not exist outside of human consciousness."

In other words, Menger invites us to consider that value exists only as a subjective psychological phenomenon within the individual, that value is not an inherent property of goods, but rather stems from the individual's opinion about the utility they can derive from those goods.

According to this view, a liter of drinking water has no objective value. Someone who has access to a modern system of drinking water and is not currently thirsty would probably assign very little value to that additional liter of water, whereas an individual who is thirsty in the middle of the desert, seeing it as the difference between life and death, would certainly be willing to attribute almost infinite value to that liter of water.

In summary, Menger noticed that the value of an economic good is nothing more than the subjective valuation that an individual assigns to an additional unit of that good or service.

Voluntary Exchange: A Positive-Sum Game

From this point, Menger deduces that voluntary exchange between two individuals takes place because each party believes it will increase their subjective utility. For him, exchange does not presuppose any equivalence of value, contrary to what the classical economists believed. According to the Austrian thinker, if there were equivalence of utility between the exchanged goods, there would be no reason for the parties to bother exchanging in the first place. If there is an exchange, it is because each party finds it in their (subjective) interest, and consequently, each voluntary exchange produces a social benefit.

Valuation as a Phenomenon of Ordering Human Desires

However, such a social benefit, or the subjective value attributed to a good, cannot be measured. For Menger, value is a cognitive phenomenon of comparison (ordinal) rather than measurement (cardinal). It is not, as the neoclassical economists have thought since Walras and Jevons, the assignment by the individual of a numerical value that reflects the utility they derive from it, but rather an act of ordering human desires by which an individual expresses that they desire a quantity of good A more intensely than a quantity of good B.

Any agent can say whether they prefer 2 bananas to an economics course, but no one can reasonably say that they value 2 bananas at 3.1416 utils, while valuing an economics course at 3 utils, and therefore, they prefer to have the bananas. Such a description of human preferences, based on continuous real functions, does not correspond to the reality of the cognitive processes we experience in our daily lives. An individual never evaluates goods presented to them by comparing them to an abstract standard of utility. Instead, he subjectively compares different courses of action, which he cannot judge in absolute terms but can nonetheless rank based on their relative desirability.

This subjective conception of value, understood as a psychological relationship that the individual entertains with his goals and the means relevant to achieve them, also allows Austrian economists to explain the phenomenon of the division of labor.

The Division of Labor

Visiting a Nail Factory, Léonard Defrance (18th century)

Everyone is unique and has a particular personal situation. Therefore, everyone possesses a superior ability to perform certain tasks than his peers (absolute advantage) or a superior ability to perform certain tasks than other ones (comparative advantage). It cannot be otherwise; to deny this elementary fact would be to claim that all humans are equal in all aspects.

In the case where an individual has a superior ability compared to their peers in the production of a given good (absolute advantage), they have an interest in specializing in the production of that good and then exchanging the surplus obtained for the goods they desire. By doing so, they satisfy their subjective utility more economically than if they were to engage in the production of all the goods they desire.

But it may also be the case that the individual does not have an absolute advantage in the production of any good. In this case, there will still be types of production for which the individual is better than in others (comparative advantage), and for this reason, they still have an interest in specializing.

Certainly, there are individuals who could produce that given good more productively than him, but since these individuals are probably more productive in another task than in this one, and since they cannot perform both tasks simultaneously, it is unproductive for them to work on this task rather than another for which they are more productive. By specializing in the task for which they are most productive, they will obtain a surplus greater than if they had not specialized, and therefore, through exchange, they could obtain an increased quantity of those other goods, even if the goods obtained would have been produced more efficiently by themselves than by the producers from whom they obtained them.

Take the example of a physician. He might be better at writing emails and scheduling appointments than his secretary (relative advantage). But any time spent at doing those tasks is time he does not employ curing patients. Hence, as he is more productive curing people, it is in his interest to delegate administrative duties to another person even if he is better at such task than his deputy, because it allows him to maximize the value generated for others, and thus its own wealth.

In essence, there is a benefit to specialization, even for individuals who do not have absolute advantages, because time is a scarce and rival resource: each unit of time spent on an activity other than the one for which an individual is most productive implies a cost represented by the foregone production they renounced (opportunity cost).

Once the individual is specialized in a particular production, they can then reserve the quantity of products they consider necessary for their personal consumption and exchange the surplus for other desired goods. In doing so, they satisfy their desire for the goods they produce themselves, which means that the remaining units of their production have little value to them. It is what economists call decreasing marginal utility: each additional unit of a good is less desired than the preceding. For others lacking such goods, it's a different story: for the same reasons, they tend to desire the goods they do not produce more intensely than those they do. This leads to a situation where there is a strong asymmetry between the various subjective valuations of individuals, which is highly conducive to exchanges: each party has an interest in exchanging their surplus production because they thereby increase their subjective utility.

The result of the preceding analysis is that individuals are always better off when they specialize in their work and engage in exchanges. Therefore, Austrian economists, especially Ludwig Von Mises, conclude that the productive advantage arising from the division of labor is the driving force behind the process of social cooperation. Here, it may be useful to quote him directly:

"The fundamental facts that brought about cooperation, society, and civilization and transformed the animal man into a human being are the facts that work performed under the division of labor is more productive than isolated work and that man’s reason is capable of recognizing this truth. […] People do not cooperate under the division of labor because they love or should love one another. They cooperate because this best serves their own interests."

Conclusion

"If a man sees that he can live more comfortably hanging from the gallows than sitting at the table, he would be acting like a fool not to hang himself."

Baruch Spinoza

1871-1874 are the wonderful years of modern economics: this period witnessed the works of three independent thinkers foundational to modern economics. With their emphasis on subjective ordinal value Austrian economists will develop a whole body of economic thought setting them apart from their homologues. The work of Austrian economists reasoning about human action in the context of scarcity will forever stand in stark contrast with the economic doctrines initiated by Jevons and Walras heavily relying on mathematics standing on the back of the idea that value can be objectively measured and derived as a continuous function.

Building on the insights of subjective ordinal value Menger explained the emergence of the division of labor and voluntary exchange. Yet as we will see in the next chapter, direct exchange is a poor strategy for economic agents seeking to maximize their subjective utility. The father of the Austrian School has thus further developed his reasoning to explained why money emerged as a social institution.

The following chapters will be dedicated to the emergence of money as a social institution, the theory of capital and interest, which will serve as the basis for the Theory of the Business Cycle, and lastly the role of prices for economic calculation.

The Emergence of Money as a Social Phenomenon

While individuals have a common interest in specialization and maximizing the division of labor, there are still coordination problems that limit this expansion.

Firstly, it is important to note that since production processes are inherently time-bound and often asynchronous (non-simultaneous), there will usually be a time gap between an individual's initial contribution and the receipt of the counterpart. Committing to a specific task now without having prior assurance that others will meet our needs in the future can be risky.

In the division of labor, each party benefits from cooperation, but individually, one might be tempted to enjoy the work of others without reciprocating, as this way, they gain something valuable without incurring any cost. Such situations, where mutual collaboration results in suboptimal gains for individuals but maximum gains for the group, are described in game theory as the "prisoner's dilemma."

The Prisoner's Dilemma

Originally, the prisoner's dilemma was formulated as follows: Two suspects, Alice and Bob, unable to communicate, are faced with the risk of imprisonment, with potential sentences as follows:

- If Alice accuses Bob, and Bob remains silent, Alice goes free, and Bob gets 3 years.

- If both Alice and Bob accuse each other, they each receive 2 years.

- If both remain silent, they each get 1 year.

These outcomes can be represented in a matrix (numerical results indicate the number of years of imprisonment):

| Alice / Bob | Accuse | Remain Silent |

|---|---|---|

| Accuse | 2, 2 | 0, 3 |

| Remain Silent | 3, 0 | 1, 1 |

In this game, there is no opportunity for coordination (communication is impossible) to achieve the best outcome for both parties. Consequently, Alice and Bob have an individual incentive to accuse each other, even though it does not lead to the optimal outcome for the group. The optimal strategy for both is to remain silent, each receiving a 1-year sentence.

This game illustrates a problem frequently encountered in real life: in the absence of coordination mechanisms, individuals tend to choose strategies that maximize their individual gain, regardless of the strategies chosen by others (theft, cheating, betrayal, violence, etc.), even when a more desirable equilibrium through coordination/collaboration is possible.

Money to Solve Coordination Problems

This problem has less impact in small communities (e.g., family, friend circles) because, in such cases, everyone knows each other directly, making it possible to remember each other's contributions. Assuming that leaving the community (desertion) incurs a cost, a reputation system based on individual agents' memory is usually sufficient to avoid the pitfalls posed by the prisoner's dilemma.

However, when dealing with larger communities that benefit significantly from the division of labor, coordination problems reemerge. This is due to two main reasons:

First, humans are limited by their cognitive capacities. It is impossible for a person to maintain and remember stable social relationships with more than 150 individuals, making a reputation system insufficient to overcome the prisoner's dilemma at scale.

Second, socially accepted measurement of the value of contributions in exchange (commensurability) is a non-trivial problem. For example, if an individual provides meat from hunting and requests materials for shelter in return, how can the amount of meat offered be evaluated in terms equivalent to the requested materials? The same goes for quality – is deer meat worth more or less than wood?

Even if it were possible to establish a satisfactory exchange rate for each pair of goods, maintaining this information quickly becomes impractical. In a direct exchange system involving N goods, there are N(N-1)/2 exchange rates to remember. For an economy of 50 goods, that means remembering 50*49/2, or 1225 exchange rates, as opposed to just 50 in indirect exchanges. For an economy of 100 goods, this number increases to 4950. Such a quadratic relationship places an additional limit on the scalability of direct exchange (barter).

Moreover, since these exchanges don't occur instantly but are spaced over time, evaluating contributions over time further complicates the relative assessment of contributions. In addition to assessing the exchange ratio between two present goods, it becomes necessary to evaluate the value of a past contribution relative to a future counterpart.

Today, despite the impracticality of such a system, we could use writing or digital data storage to remember all this information and establish a credit system (keeping track of past contributions, including the exchange rate of those contributions, is essentially setting up a credit system).

In pre-civilization times, these technologies did not exist. Thus, our ancestors had to find other solutions to enjoy the benefits of the division of labor without exposing themselves to the negative consequences of the prisoner's dilemma. The solution to this problem of direct exchange was indirect exchange facilitated by money.

Double Coincidence of Wants and Salability

Money can be seen as the solution discovered by our ancestors to address what economists call the "double coincidence of wants" problem. This problem has three dimensions: spatial, temporal, and interpersonal.

In a direct exchange (barter) between Alice and Bob, they both need to possess something the other desires at the same time and place. By using indirect exchange, i.e., through money, Alice can buy from Bob, and Bob can use that monetary unit elsewhere, at another time, and with someone else (provided that the other person accepts that form of money).

For a good to serve as money, it must have a high salability, meaning it should be desired by as many people as possible, most of the time. By using a highly saleable good, the problem of double coincidence of wants is resolved in terms of spatial and interpersonal dimensions: if the good I use as money is desired everywhere and by most people, I can easily separate the act of selling from the act of buying in terms of location and social interaction.

However, the salability problem over time is more challenging to solve for two reasons:

First, entropy (commonly known as the "effect of time") gradually alters the qualities of most goods with direct utility. Therefore, preserving the salability of a good over time requires it to be highly durable or resistant to entropy.

Second, the relative scarcity of a good at time "t" does not guarantee its relative scarcity in the future. By dedicating enough resources to a specific area of production, humans can increase the supply of any good. The only limitation to increasing the production of a good is the associated opportunity cost. Consequently, the present relative scarcity of a good cannot guarantee its future relative scarcity. Only goods whose marginal production can be increased at very high costs can be consistently scarce, which is why this is a characteristic of freely emerged monetary goods throughout human history.

In pre-civilizational times, a variety of goods like seashells, crafted jewelry, necklaces, or beads served as money. These goods were easily transportable, had no direct utility beyond their ornamental value, resisted entropy (i.e., they did not deteriorate over time), were naturally scarce and/or required a significant amount of specialized labor to produce. Since the level of division of labor was low at the time, and therefore, the opportunity cost associated with producing ornamental artifacts was high, these items could not be produced in large quantities. Thus, those using these items as money could be assured of their future relative scarcity.

The fact that our hunter-gatherer ancestors engaged in these resource-intensive tasks, even though they generated no goods with direct utility, demonstrates the significant gains they expected from expanding the spatial, social, and temporal scope of exchange. If this were not the case, and it were more useful for them to employ these resources in shelter construction, hunting, or other activities, rather than the production of monetary goods, we would probably not find as much archaeological evidence of these artisanal activities. Other groups using their resources more efficiently would have enjoyed better development and greater prosperity, and these artisanal activities would have quickly disappeared in favor of activities producing goods with direct utility.

In this sense, the production of monetary goods, by promoting the expansion of the division of labor, represented a more profitable use of resources (in terms of subjective utility to individuals) than all other alternatives (increasing hunting, fishing, gathering, wood production, house construction, producing more hunting and fishing tools, etc.).

Uncertainty

To conclude our analysis of the monetary institution, we need to address the issue of economic action in the context of the inevitable uncertainty about the future.

As Austrian economists have pointed out, human action is time-bound and always oriented toward the future. When an individual acts, they change their present condition in the hope of obtaining future satisfaction. This mental projection can be oriented toward the near or distant future, but for an individual to project into the long term, they must first secure their short-term sustenance because their condition in the near future directly affects their condition in the distant future.

This stems directly from human rationality; no one can ignore the sequential nature of temporal phenomena and the chronological dependence that results from it because it's one of the essential constraints of human life. Therefore, since the future always remains uncertain for humans, they will seek to secure their long-term survival only once their short-term survival is assured.

In this regard, money, by allowing the storage of value in the present and its transfer to one's future self, plays a crucial role in the intertemporal coordination of human action. By storing money, i.e., saving, individuals guard against future uncertainty and thus enable themselves to direct their actions toward longer time horizons. However, they can only achieve this if the money used constitutes a store of value, meaning it has salability over time, which, as previously mentioned, is a characteristic of durable and relatively scarce goods.

In the next chapter we will delve into the concept of time preference and explain the Austrian perspective on interest and capital, which will serve as basis for the following chapter about the Theory of the Business Cycle.

Time Preference, Interest, and Capital

Time Preference

We concluded the last chapter by explaining how economic agents use the most salable good, i.e. money to stave off future uncertainty. We also explained that the sequential nature of temporal phenomena leads us to fight uncertainty gradually: only when we know that our subsistence will be assured for the next week can we concentrate toward goals farther into the future.

Or, to say it differently: as human beings we discount the value of future goods.

This subjective evaluation of the value of future goods compared to present goods is referred to as time preference. All else being equal, present goods are inherently preferred over future goods. Since we are mortal, and the future is always uncertain, we naturally prefer to have access to a good now rather than later. While time preference can differ between individuals, due to a myriad of factors such as culture, wealth, education, physiology, etc., time preferences are always positive, meaning that all things equal, we always value present goods more than future goods.

This concept of relative valuation of future goods over present goods is at the root of the phenomenon of interest. Indeed, in an economy with unmanipulated capital markets, reference interest rates (considered risk-free from default) are determined at the intersection of capital supply and demand. Therefore, these rates represent the state of time preferences for the entire economy: an increase in the interest rate results from a relative increase in demand for capital compared to supply, indicating higher time preferences. Conversely, a decrease in interest rates occurs due to an increase in savings, which is an increase in the supply of capital, indicating a reduction in time preferences.

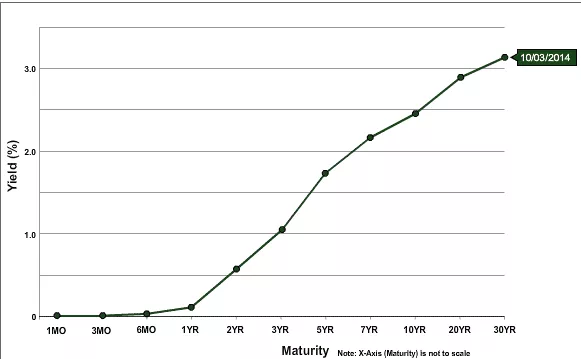

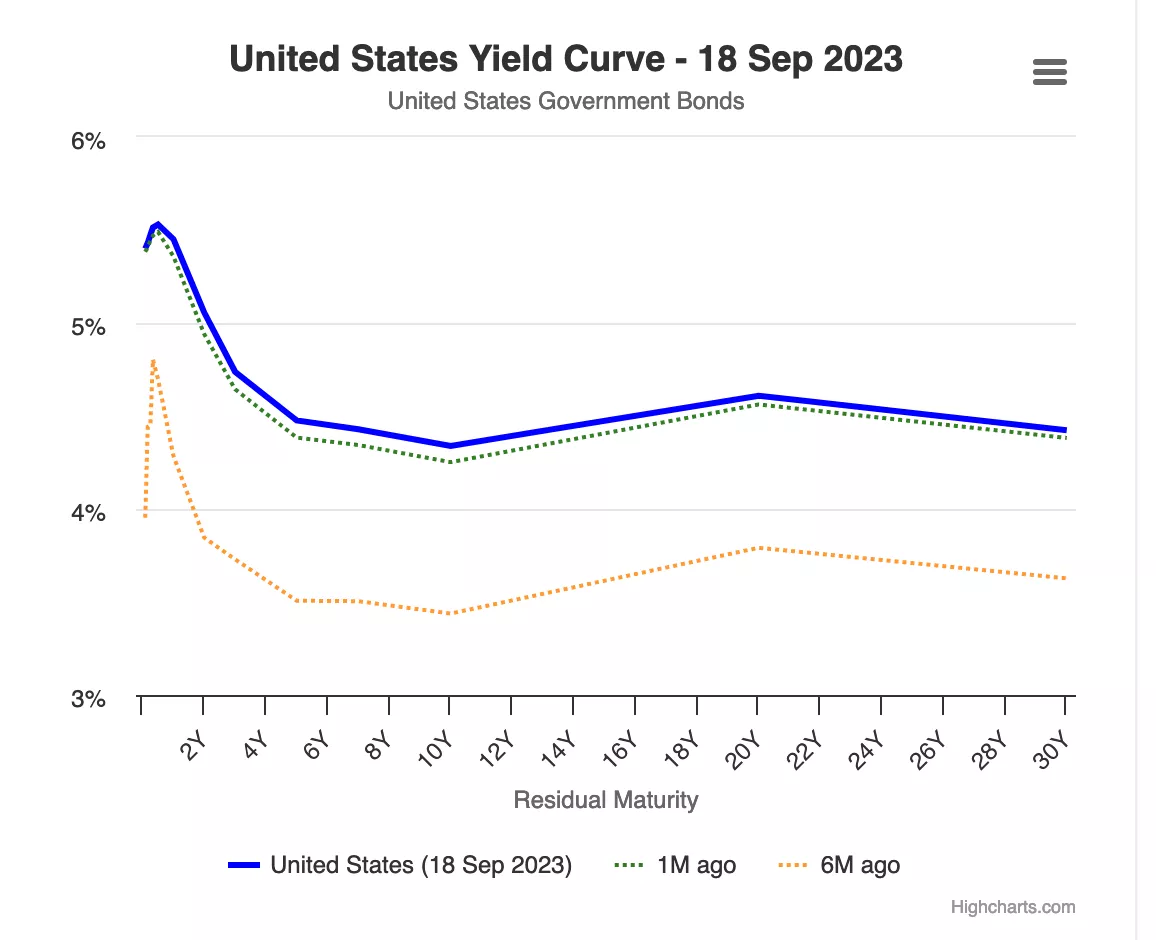

In an economy where interest rates are not manipulated by the central bank, we tend to observe an upward-sloping yield curve: the longer the maturity of the debt, the higher the interest rate. The opposite situation can’t happen because it would entail that the future is more certain than the present, which is a logical impossibility.

The concept of time preference and how we express our own time preference by act of consumption and savings is fundamental to the processes of capital allocation and production. Let’s turn to Menger’s student, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, and his capital theory to understand exactly how time preference affect the organization of production.

Capital Theory

At the beginning of this course, we saw that, for Carl Menger, goods are only considered economic goods (valued) because they serve as means to ends chosen and valued by individuals. According to this view, all economic analysis revolves around consumption because it is ultimately the motivating objective behind all economic activity. Therefore, for Menger, the starting point of economic analysis is consumer goods, or final goods, as they represent the ultimate purpose of economic activity. All other goods in the economy, which we can call "intermediate goods," only have value because they enable individuals to obtain these consumer goods: they are goods used in the production of other goods.

To produce consumer goods, entrepreneurs combine these various intermediate goods with original factors of production (labor, land, and capital) according to a pattern that maximizes the resulting production. This arrangement, made by entrepreneurs, or the production structure, includes various stages during which intermediate goods undergo transformations until they eventually become consumer goods.

Thus, like Menger, we can define consumer goods as first-order goods, goods involved in the previous stage as second-order goods, those in the stage before that as third-order goods, and so on, until we reach the original factors (land, labor, capital). The number of stages we consider fundamentally depends on the production structure adopted by entrepreneurs and should not be seen as an objective characteristic of the production structure. On the contrary, production stages and intermediate goods only exist within a teleological context: the actor envisions a sequence of actions through which they will achieve their desired objective, and they mentally divide their action into successive stages.

This characteristic of mental projection of action in a sequential pattern is imposed by the temporal nature of human action. Each action undertaken by humans takes time; immediate action is impossible. Therefore, the actor always has a choice among action patterns that take more or less time.

Henceforth, since individuals necessarily have positive time preferences, meaning they prefer present goods to future goods, they will only choose a longer path if the result obtained has greater subjective value for them than what they would have achieved by taking the direct path. Otherwise, no one would adopt more time-consuming methods: under equivalent results, the shortest path remains the preferred choice.

Due to the sequential nature of human action, these intertemporal choices always have implications for the action sequence. In other words, the short-term actions I take are subordinate to the long-term goals I set, and my short-term actions will influence what I can do in the future. The implication of this obvious point concerning production activities is that any production detour, i.e., any lengthening of the production structure, requires prior saving. If I decide to allocate more resources in the present to achieve a future goal, I must first set aside what will sustain me during the time my investment takes.

To illustrate this point, let's revisit the example given by Böhm-Bawerk, in his work "Capital and Interest":

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (1851-1914)

Robinson Crusoe and Production Detour/Roundabout:

Robinson Crusoe Landing Stores from the Wreck, John Alexander Gilfillan (1793-1864)

In his book, the Austrian economist invites us to consider the intertemporal trade-offs inherent in production detours through a thought experiment based on Robinson Crusoe alone on his island.

Robinson, like a primitive human, depends on foraging and hunting for his sustenance. Let's imagine that Robinson can gather enough berries to feed himself for a whole day in eight hours. In such conditions, he has little time for other activities. However, Robinson believes that by making a wooden pole, he could easily knock down the berries and obtain his daily food in just four hours of work. Furthermore, he estimates that it will take him five days, working two hours each day, to make the pole. Therefore, he concludes that he needs to save 1/5th of his berry production for five days, or alternatively spend an additional 2 hours per day on gathering for 5 days, to save enough berries to sustain himself during the time he spends making the pole.

If he doesn't make this prior saving, Robinson will be unable to complete his pole and might die in the meantime.

So, for five days, he sacrifices two hours of his rest to gather more berries. At the end of this period, he has enough berries and begins crafting the wooden pole, working two hours a day for five days. Once his work is done, he can obtain enough berries for his daily portion in 4 hours instead of 8, allowing him to use the remaining 4 hours a day for other activities.

By acting this way, Robinson takes a production detour: instead of directly gathering the berries, he invests effort in producing a capital good that will make him more productive in the future. However, he must make a short-term sacrifice, i.e., save, to achieve this. If he didn't, he would be unable to complete his capital good. This short-term sacrifice, however, provides him with a significant advantage since, once equipped with his pole, he gains 4 hours per day (until the pole becomes obsolete). These 4 extra hours per day enable him to create more capital goods, such as hunting tools or fishing nets, gradually improving his situation.

Conclusion

In other words, in Robinson Crusoe's one-person economy, saving through the sacrifice of present satisfaction is what accumulates the capital that increases productivity. In this context, saving, i.e., deferring present satisfaction, is the price to pay for increased future satisfaction. This means that, in this context, saving is the prerequisite and necessary condition for any economic development.

This is a tantalizing, albeit simple, concept: any extension of the production structure requires prior savings (as the goods needed for such production won’t fall from the sky), and thus, the more we save, the more capital we will be able to accumulate, which will in turn translate into productivity gains yielding more goods. Thus, Austrian economists consider that the lowering of time preferences is the starting point for a virtuous cycle of savings –> more capital goods more productivity more goods = higher standard of living –> lower time preference.

Now, as eluded in the first chapter, interest rates have been manipulated for decades by central banks all the while commercial banks extended credit without prior reserves, meaning that interest rates don’t represent our time preference and gives an illusion of abundant savings.

This is perfectly illustrated by the chart below: long-rates are lower than short-rates. First, this makes absolutely no sense, because it would entail that the future is more certain than the present. Second, it warrants an inquiry about the consequences for capital allocation: if everyone is incentivized to act as if savings were abundant, whereas savers are nowhere to be found because they are not rewarded for saving, what consequences could this yield for the economy?

This is what we will find out in the next chapter dedicated to the Austrian Theory of the Business Cycle!

Austrian Economic Perspectives

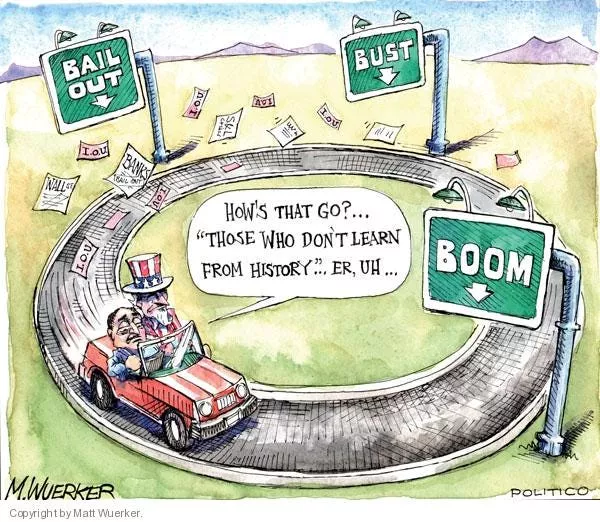

The Austrian Theory of the Business Cycle

“The longer the boom of inflationary bank credit continues, the greater the scope of malinvestments in capital goods, and the greater the need for liquidation of these unsound investments. When the credit expansion stops, reverses, or even significantly slows down, the malinvestments are revealed”

Ludwig von Mises

It was Ludwig Von Mises, the most accomplished student of Böhm-Bawerk and arguably the most important Austrian economist of the 20th century, who used Böhm-Bawerk's capital reasoning to explain the causes and dynamics of economic cycles. Friedrich A. Hayek, Mises's protege, later extended this reasoning to its logical conclusions in works for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1974.

Mises and Hayek began their analysis with an increase in savings as the starting point. As we have seen in the previous chapters, any increase in savings necessarily entails a corresponding decrease in consumption and thus lower relative prices of consumer goods. This leads to two effects: firstly, an increased demand for capital goods caused by rising real wages resulting from the relative decrease in the prices of consumer goods; and secondly, an increase in entrepreneurial profits at the stages of production farthest from consumption (lower order). As real wages rise, entrepreneurs are incentivized to economize labor by using more capital goods, which creates a stronger demand for capital goods and higher profits for entrepreneurs producing these lower order goods. Thus, in the context of increased savings, i.e. a decrease in time preferences, interest rates fall, promoting the development of additional stages of production and increased productivity. This is a classic Böhm-Bawerkian production detour, and it is a highly desirable outcome.

However, the two Austrian economists pondered what would happen if the decrease in interest rate, which serves as the starting point for this production detour, did not result from an increase in savings but instead from credit expansion.

In the context of fractional reserve banking, credit expansion does not require a corresponding increase in savings. Therefore, entrepreneurs can raise more capital and engage in production detours even as time preferences remain unchanged, i.e. without any decrease in consumption. For Hayek and Mises, such a situation should necessarily lead to significant coordination problems among economic agents. Due to the lack of free-market interest rates, these problems may not be immediately evident, but in the long run, the resulting misallocations of capital should produce tangible consequences: a recession.

To describe this phenomenon of temporal miscoordination and its consequences as clearly as possible, we will rely on a model of the production structure and observe how it is affected, first by a decrease in interest rates resulting from an increase in savings, and then by a decrease in interest rates caused by an expansion of credit.

Decrease in Interest Rates Due to an Increase in Savings:

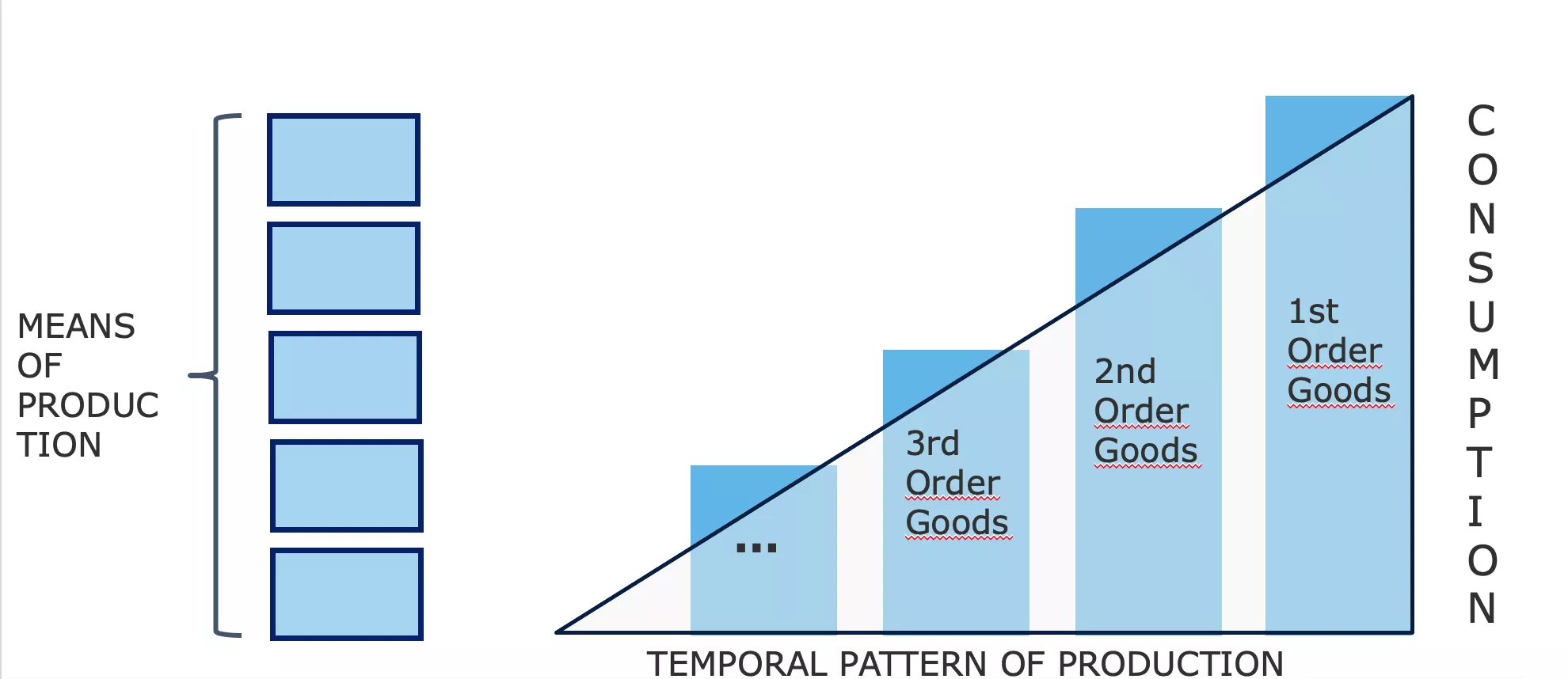

To facilitate our explanation, we will return to Menger's classification of goods and represent the productive structure on a diagram consisting of an arbitrary number of stages:

In the above diagram, initial resources pass through various stages of production, undergoing transformations that bring them closer to the state of final consumer goods (through interaction with original factors of production: time, land, labor). The height of the right side of the triangle schematically represents GDP since it denotes the sum of all consumer goods sold in a period. The gap between each bar corresponds to the value added (in monetary terms) generated by each stage of the process. This difference can also be seen as the income associated with each stage (revenues - costs).

If, at the aggregate level, economic agents increase their savings, the quantity of final goods consumed will decrease - all else being equal, saving necessarily involves postponing part of one's consumption to a later date. As a result, interest rates will fall - because the supply of capital is increasing, allowing entrepreneurs to use this influx of capital to create new investment goods and thus lengthen the production structure.

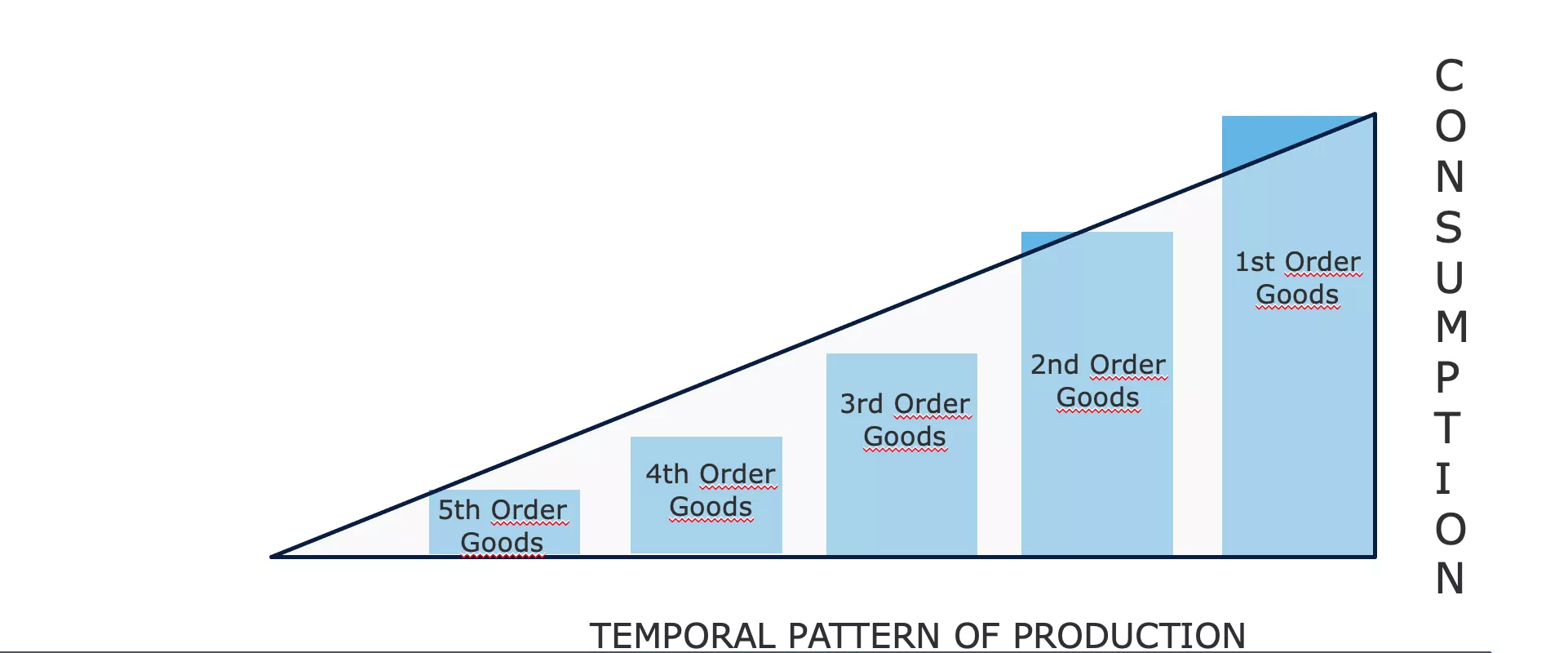

We will then obtain an extended production structure, a change that can be qualitatively represented by the following diagram:

Here, the monetary value of demanded consumer goods has decreased, freeing up resources for the creation of an additional stage of production. In this scenario where the decrease in interest rates is a consequence of decreased consumption, i.e., increased savings, the area of the triangle, representing the quantity of money in circulation, remains unchanged. The transformation of the production structure (lengthening) simply results from a transfer of purchasing power from one part of the structure to another.

It is also noteworthy that the reduction in demand for consumer goods will cause, in the medium term, a decrease in consumer prices rather than a decrease in the quantity of final goods offered. This is because the final part of the production structure will not adjust immediately after the drop in demand for consumer goods occurs; entrepreneurs will take some time to alter their plans and investments. As they hold inventories, the decrease in demand will force them to sell these inventories at a discount, and, consequently, the surplus of savings will initially result in lower prices for consumer goods (i.e., an increase in real wages).

Conversely, investment goods will see their prices rise because the transfer of purchasing power to entrepreneurs enables them to increase their investment expenditures. Once this savings, transferred by savers to entrepreneurs, is spent by the latter, interest rates will tend to rise again (due to a reduced supply of capital), which in turn will lead to lower prices for investment goods. In fact, at the end of this production detour, relative prices will remain roughly the same as before. But economic agents overall benefited: increased productivity resulting from the lengthening of the production structure will offer consumers more products at lower unit prices; the purchasing power of savers will increase, partly through interest earnings and partly due to lower consumer prices; meanwhile, entrepreneurs, considered as a whole, will experience neither gains nor losses. Those engaged in activities closest to consumption will lose income, while those involved in creating new stages of production will gain proportionally. In such a situation, no new monetary income is created; it is production that increases, and thus the real value of incomes rises.

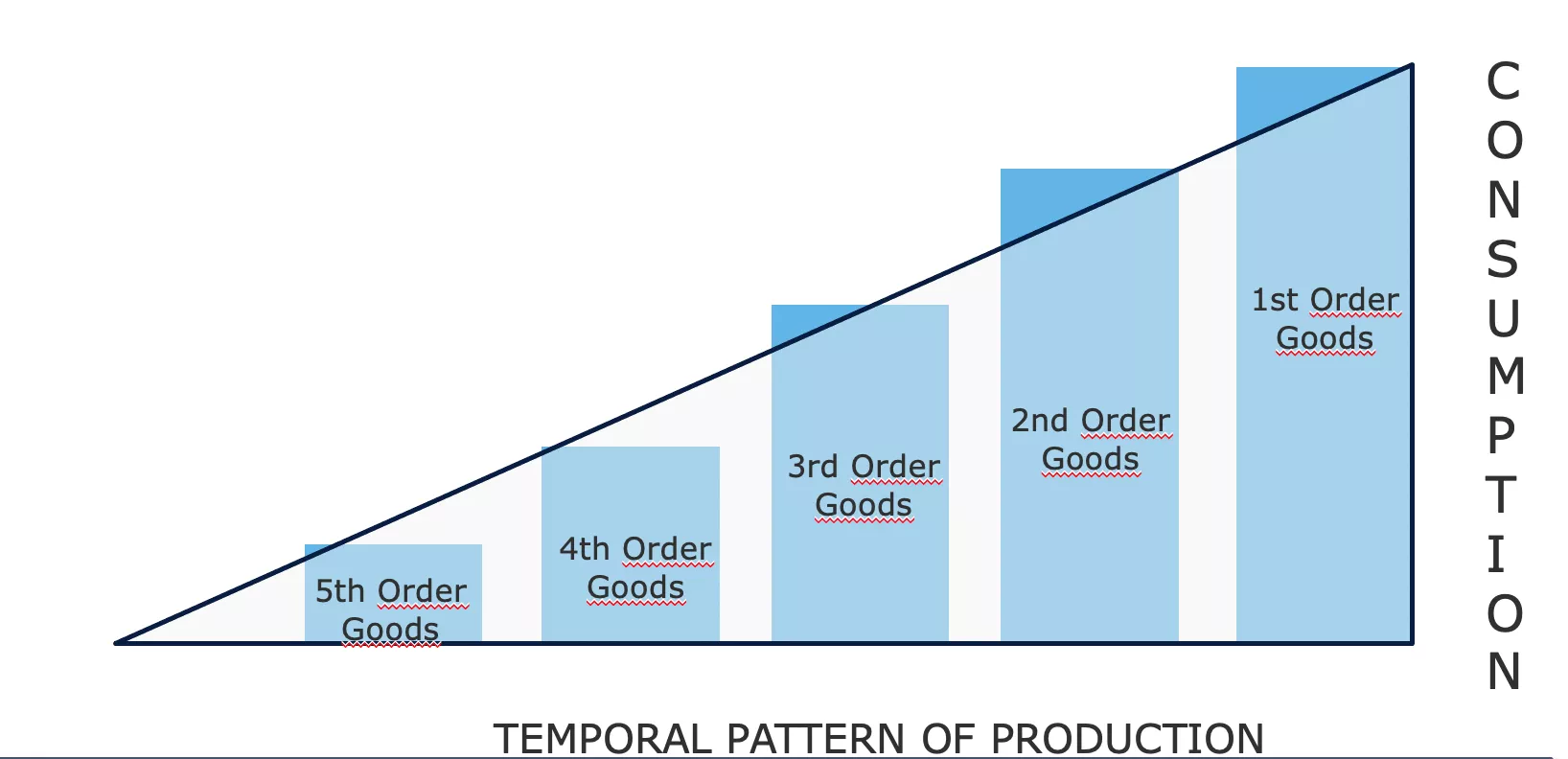

Decrease in Interest Rates Due to an Increase in Credit (No Increase in Savings):

Now, if we consider a decrease in interest rates resulting from an expansion of credit offered by banks, we obtain a very different picture of the production structure.

With lower interest rates, entrepreneurs can borrow more resources and thus create higher order production stages. In this case, such an extension of the production structure will not result in decreased consumption because there has been no consumer postponement of present consumption. In other words, GDP grows. Consequently, our triangle will lengthen while maintaining a similar height, meaning its area will increase.

Note that this is a completely logical consequence of the credit expansion. Insofar as banks produce fiduciary media by granting loans, one should naturally expect overall purchasing power to increase.

As credit enters the economy through loans to entrepreneurs, we should observe an increase in profits in the production sectors distant from consumption, and a decrease in relative profits in sectors closer to consumption. This higher profitability then supports a reallocation of capital towards these new, more capital-intensive stages (shipbuilding, automotive, construction, advanced technologies, etc.), and a decrease in investments in sectors closer to consumption.

Now, the entrepreneurs involved in these higher stages of production earn higher monetary incomes, and, as time preference remained the same, we should also see increased demand for consumer products. But as, during this boom, the relative profitability of invested capital has been higher in sectors far from consumption, there has been a transfer of resources from activities close to consumption to more distant activities. Consequently, the entrepreneurs in lower stages of production lack the resources to meet the increased demand. This creates tension between these two parts of the production structure: each tries to obtain capital at the expense of the other, and since the demand for consumption represents more urgent needs, at some point, entrepreneurs engaged in activities distant from consumption will run short of the resources needed to complete their investments. The profit rate in these sectors then starts to decline, businesses go bankrupt, and the relative increase in consumer prices motivates a rapid reallocation of capital toward the production of lower-order goods. When this sudden resource reallocation manifests, the economy enters a recession: asset prices fall, real wages decline, consumer prices fall, and inventory piles up.

For Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises, the recession is the manifestation of the misallocation of capital from the expansion phase. As prices for savings and capital were manipulated, entrepreneurs developed projects which could not be finished by lack of resources, and/or build productive capacity planning for a future level of consumption which could not be sustained due to a lack of savings.

Only through deflation, i.e. decline in asset prices and wage prices, higher interest rates, and the liquidation of unfinished projects can the economy readjust and develop toward a sustainable path. So, the recession is the dissipation of this illusion of prosperity triggering a violent readjustment process.

In general, the recession is triggered by the banking sector itself. As long as credit is increasing at an accelerating pace, prices continue to rise, and entrepreneurs compete for productive resources. However, as noted by Hyman Minsky, there comes a point where the banking sector decides to reduce its risk, therefore diminishes the flow of credit. The depression, therefore, results in many bankruptcies, credit tightening, a decrease in available purchasing power, and financial meltdowns.

Such an adjustment can be viewed as a period during which underconsumption, and underinvestment are enforced to rebuild the missing savings. For Hayek, this depressive stage, although painful, is highly necessary as it allows for a recovery of economic activity based on a structure of relative prices reflecting the actual scarcity of production factors. If this depression is interrupted, the economy cannot return to a desirable path because, in the absence of an information system allowing economic agents to rationalize their decisions, the misallocation of resources will only continue.

Unfortunately, this depressive mechanism is often interrupted by political power and central banks seeking to “boost” the economy through deficit spending and easy monetary policy.

For both monetarists and Keynesians, the cause of the depression is insufficient aggregate demand, so neither pays attention to the evolution of relative prices, which, as we have seen, is the core of the problem. Thus, they believe that providing an incentive for credit expansion (lowering interest rates) and using the state's deficit capacity to boost demand will kickstart a recovery. In the short term, such measures may seem to produce the desired effects: the deficit supports spending, while the reduction in interest rates leads to higher asset prices, which, in turn, encourages asset holders to increase their spending. However, such boost eventually wanes off, while the structural problem remains, or even worsen as capital misallocation continues thanks to artificially low interest rates.

In the modern era, central banks and governments have been so zealous in preventing the manifestation of this adjustment process that we end up with mass structural unemployment and perpetual debt accumulation. Japan serves as an example in this regard. After the burst of an asset bubble in 1989-90, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) and the various governments in office used all the methods described here to try to "restart the Japanese economy." Apart from brief surges following spending programs and interest rate cuts, Japan has remained in a state of neurasthenic growth and over-indebtedness for 30 years.

Conclusion on the Business Cycle Theory:

By emphasizing the sequential nature of human action and paying particular attention to the impact of interest rate fluctuations on the intertemporal coordination of economic agents, Ludwig Von Mises and Friedrich Hayek explained economic cycles as endogenous dynamics of the fractional reserve banking system. The difference between the Austrian analysis and that of monetarists and Keynesians largely lies in the fact that the former pays particular attention to the various stages of production and the structure of relative prices, whereas the latter stops at aggregated variables such as employment levels, GDP, or the consumer price index. Indeed, as they lack a capital theory, mainstream economists tend to attribute the causes of the recession to “animal spirits” or “external events”.

More than any other school of economics, the Austrian School insists on the importance of relative prices to coordinate economic agents. Members of the Austrian School have been dragged into debates on the matter for more than a century, especially so since Mises published his work on the impossibility of economic calculation in socialist economies in 1919.

This will be the subject of the next and last chapter of this course.

The Impossibility of Economic Calculation under Socialism

“Where there are no market prices for the factors of production because they are neither bought nor sold, it is impossible to resort to calculation in planning future action and in determining the result of past action. A socialist management of production would simply not know whether or not what it plans and executes is the most appropriate means to attain the ends sought. It will operate in the dark, as it were. It will squander the scarce factors of production both material and human (labour). Chaos and poverty for all will unavoidably result”

Ludwig von Mises, Planned Chaos

The Impossibility of Economic Calculation under Socialism

Despite the repeated failures of Marxist regimes over the last century, the economic calculation debate remains pertinent for two significant reasons:

- Comparable ideas are still advocated by progressives and other interventionists.

- Price-fixing, whether in capital markets through the actions of central bankers or in other markets through state-owned enterprises, decrees, and the intervention of regulatory committees, continues to be prevalent.

The Economic Calculation Debate

This debate was initially ignited by one of the most influential economic papers of the 20th century, "Economic Calculation in a Socialist Commonwealth," authored by Ludwig von Mises and published in 1920. During that era, socialism was on the rise, with the Bolsheviks seizing power in Russia, socialists taking office in the Weimar Republic (Germany), and socialist and communist parties gaining prominence across Europe.

Before Mises's article, debates on socialism and capitalism primarily revolved around moral arguments and the incentive problem. Even if one assumed that a society organized around the Marxist principle of "from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs" was morally superior, the practical question of "who will take out the garbage" still needed to be addressed. The common response was that socialism would produce individuals devoid of capitalist instincts, willingly serving their peers even in the absence of monetary incentives.

With his article, Mises introduced a new dimension to the debate. Setting aside utopian notions about the ability of a political economy to create a "new man," the Austrian economist pointed out that rational economic organization was impossible without prices for the intermediate factors of production. Even today, his argument remains poorly understood by his critics, and even by some liberal economists. Thus, it is worth explaining it in greater detail.

Explaining the Impossibility of Economic Calculation

Most misconceptions about Mises's arguments arise from a misunderstanding of the roles played by managerial and entrepreneurial classes in a capitalist economy. Mises never dismissed the ability of managers to devise efficient production plans within their own operations. Instead, he emphasized the significance of entrepreneurs and shareholders, who, as owners of the means of production, allocate capital across different industries, thereby forming prices that serve as inputs in the economic calculations of managers.

Without markets for capital and money, it becomes impossible to rationalize the use of resources across industries. This means that even if there is perfect organization within each firm or subpart of the economy, the entire economy cannot efficiently adjust to changes in resource availability, production conditions, and consumer preferences. In Mises's words:

"[...] the cardinal fallacy implied in [market socialist] proposals is that they look at the economic problem from the perspective of the subaltern clerk whose intellectual horizon does not extend beyond subordinate tasks. They consider the structure of industrial production and the allocation of capital to the various branches and production aggregates as rigid and do not take into account the necessity of altering this structure to adjust it to changes in conditions.... They fail to realize that the operations of corporate officers consist merely in the loyal execution of the tasks entrusted to them by their bosses, the shareholders.... The operations of managers, their buying and selling, are only a small segment of the totality of market operations. The market of the capitalist society also performs those operations which allocate the capital goods to the various branches of industry. The entrepreneurs and capitalists establish corporations and other firms, enlarge or reduce their size, dissolve them, or merge them with other enterprises; they buy and sell the shares and bonds of already existing and new corporations; they grant, withdraw, and recover credits; in short, they perform all those acts, the totality of which is called the capital and money market. It is these financial transactions of promoters and speculators that direct production into those channels in which it satisfies the most urgent wants of the consumers in the best possible way."

Mises, Human Action, pp. 703-04

In essence, Mises argues that property rights, which place capital owners in a context of profits and losses, motivate them to allocate their resources to industries that are currently most in need of resources to satisfy consumer demands. When they succeed, they profit, but when they fail, they incur financial losses. Their "skin in the game" encourages them to speculate about the best allocation of capital for the current state of the economy. This creates a market-driven dynamic where the collective outcomes of their actions produce vital information about the most efficient use of resources.

Prior chapters have explained that values are subjective, economic actions reveal opportunity costs, and consumer prices express an ordinal hierarchy of consumer wants. Entrepreneurs compete for factors of production to construct production structures that maximize revenues over costs, satisfying consumer desires more effectively than alternative options. Therefore, prices of factors of production are derived from consumer prices: if a factor of production can generate greater monetary revenue (better satisfying consumer wants) in another industry or under a different plan, entrepreneurs will outbid its current owner, raising its price to its marginal productivity. This competition among entrepreneurs for factors of production, determining their highest marginal yield, is a process that generates relevant information about resource allocation.

This process is crucial because it validates or invalidates the efficiency of various activities, ensuring that factors of production are allocated to their most productive uses. The market performs this function as a continuous process. In a constantly changing world—where consumer preferences, production conditions, technology, regulations, demographics, and more are in flux—prices for intermediate factors of production continually change through the actions of entrepreneurs and capitalists adapting to shifting conditions. Since these changes are localized, information must be disseminated to economic agents who cannot possess complete knowledge of the entire world. This is the role of the market: it allows entrepreneurs to act on localized, often qualitative, and complex information by proposing economic production structures that are then validated or invalidated by the market. In this way, pertinent information generated by this bottom-up process is condensed and distributed throughout the entire economy via the price system. This process of information production and distribution is essential for resource allocation because it enables economic agents, who have limited knowledge of the world, to make economic calculations and devise coherent economic plans by relying on prices.

From this perspective, a centrally planned economy will inevitably experience capital misallocation. In the short to medium term, such misallocations might go unnoticed because there are no market prices or bankruptcies to reveal them. However, due to the absence of feedback (prices) and reallocation mechanisms (bankruptcies), errors will accumulate until the wastefulness becomes apparent through a significant decline in living conditions.

The Austrian Perspective and the Failures of Other Schools of Economics

One could argue that painting such a panorama in hindsight is easy. After all, we are all aware of the empty shelves in the USSR, Venezuela's hardships, and the humanitarian catastrophe in Cambodia. But Mises foresaw these events as early as 1920. Yet, until the collapse of the USSR in 1989, many economists, including numerous Nobel laureates, were praising the Soviet economic miracle and predicting that the Soviet economy would soon surpass that of the USA.

Despite this impressive forecasting and numerous empirical demonstrations of the impossibility of economic calculation under socialism, political leaders worldwide are more eager than ever to set prices, nationalize entire industries, and propose five-year plans, often applauded by economically uninformed populations. The consequences of such interventionism are acutely felt by people in formerly prosperous Western countries who are slowly witnessing the decline of their living standards.

The Austrian Business Cycle Theory as a Specific Case of the Impossibility of Economic Calculation under Socialism

In a previous chapter, we elucidated the dynamics of overinvestment and capital misallocation resulting from interest rate manipulation by central banks. Essentially, what we explained can be viewed as a specific case of the impossibility of economic calculation under socialism, applied to the realm of money markets. When prices are fixed outside their market values, entrepreneurs and capital allocators are incentivized to engage in investments that cannot be sustained in the long term due to a lack of savings. By interfering with the price system, central planners (in this case, central bankers) create a miscoordination between economic agents. In this instance, the intertemporal miscoordination entails overinvestment in higher-order investment goods and underinvestment in lower-order investment goods, which represents a specific manifestation of capital misallocation across industries.

The consequences of such misallocation include financial and economic crises, reduced economic activity, and debt deflation. These macroeconomic effects stem from an imbalance between savings and investments resulting from credit expansion. In the USSR and other communist regimes, price fixing led to similar miscoordination, resulting in shortages of some goods and overproduction of others. In both cases, prices fail to reflect the true preferences of consumers, whether in terms of time preferences or consumption preferences, leading entrepreneurs or central planners responsible for resource allocation to invest capital in the "wrong industries."

Today, the economic calculation debate resurfaces primarily in discussions about energy, where malinvestments driven by a green agenda are becoming increasingly evident. It also arises in discussions about money markets, with Austrian economists pointing out that the 2008 crisis, which mainstream economists failed to predict, was a classic boom and bust cycle characterized by overinvestment in the housing market due to prolonged periods of low interest rates. Furthermore, neo-Marxists and other socialist factions propagate the notion that the emergence of AI could resolve the economic calculation problem. However, this perspective stems from a flawed understanding of the issue; the economic calculation problem is not a matter of computing power but rather a matter of generating and distributing information related to production and resource allocation. This information can only be generated locally by agents with specialized knowledge and a vested interest in the outcome. AI cannot replace this bottom-up process and, therefore, cannot help central planners address the resource allocation problem. Unfortunately, due to a century of misunderstanding, we anticipate a proliferation of claims that AI will usher in a new era of economic prosperity led by enlightened central planners who, with the aid of AI, can correct the failures of free markets.

For a concrete application of the economic calculation problem to a contemporary situation, you can refer to this article tackling the problem of resource allocation in modern China.

The Road to Financial Repression: China the Paper Tiger, Theo Mogenet, https://open.substack.com/pub/theomogenet/p/the-road-to-financial-repression-181?r=ccpx8&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

Conclusion

In this final chapter, we have explored the impossibility of economic calculation under socialism, a central tenet of the Austrian school of economics. The Austrian perspective presented in this course culminates in this conclusion and provides a strong case for non-interventionist policies. At its core, all Austrian thinking revolves around the importance of prices in economic coordination. By emphasizing the significance of opportunity costs and economic calculation for rational resource utilization, Austrian economists demonstrate the complexity and subtlety of human action in an ever-changing world.

Mainstream economists and central planners often dislike Austrian economists because they highlight the uncertainty of the future, the fallacy of quantitative economic prediction, and the detrimental effects of economic intervention. In short, Austrian economics underscore the ineffectiveness and harmful consequences of interventionist actions.

The Austrian tradition embodies a humble approach to human action, drawing profound implications from the concepts of subjective value, uncertainty, free will, and complexity. It explains how the market order, despite not being a product of human design, stands as the central institution for our development and prosperity. If there's one key takeaway from this course, it is that capitalism became the dominant economic system because of its ability to adapt to change in a dynamic and uncertain world populated by free individuals.

The Austrian Methodology

The Austrian school of economics distinguishes itself from other schools by its axiomatic-deductive methodology, which differs from the positivist approach often used in social sciences. The positivist approach is based on laws established from empirical data, adopting a method similar to that of physical sciences. It formulates hypotheses from observations, which are then confirmed or refuted by temporary experiments. The scientific method consists of retaining the hypothesis that best explains the data and continuing to explore it until a more precise hypothesis is found.