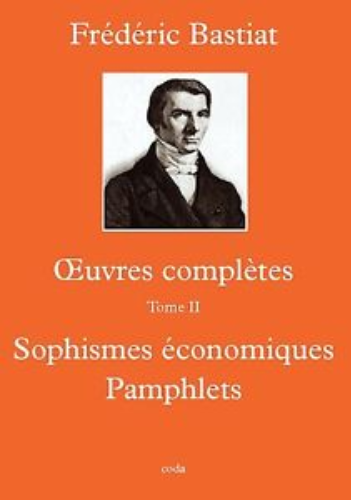

name: Frédéric Bastiat, Life, Influences, and Economic Thought goal: To gain a deep understanding of the life, influences, opponents, and economic theories of Frédéric Bastiat, a 19th-century French economist and thinker. objectives:

- Learn about the life and historical context of Frédéric Bastiat.

- Understand the intellectual influences on Bastiat.

- Examine Bastiat's ideological opponents.

- Analyze economic sophisms according to Bastiat.

A Journey Into the World of Frédéric Bastiat

This course, led by Damien Theillier, invites you to dive into the world of Frédéric Bastiat, a French economist and philosopher whose ideas continue to influence contemporary economic thought. Through 21 videos, Damien Theillier explores Bastiat's life, his intellectual influences, his ideological opponents, as well as his economic theories.

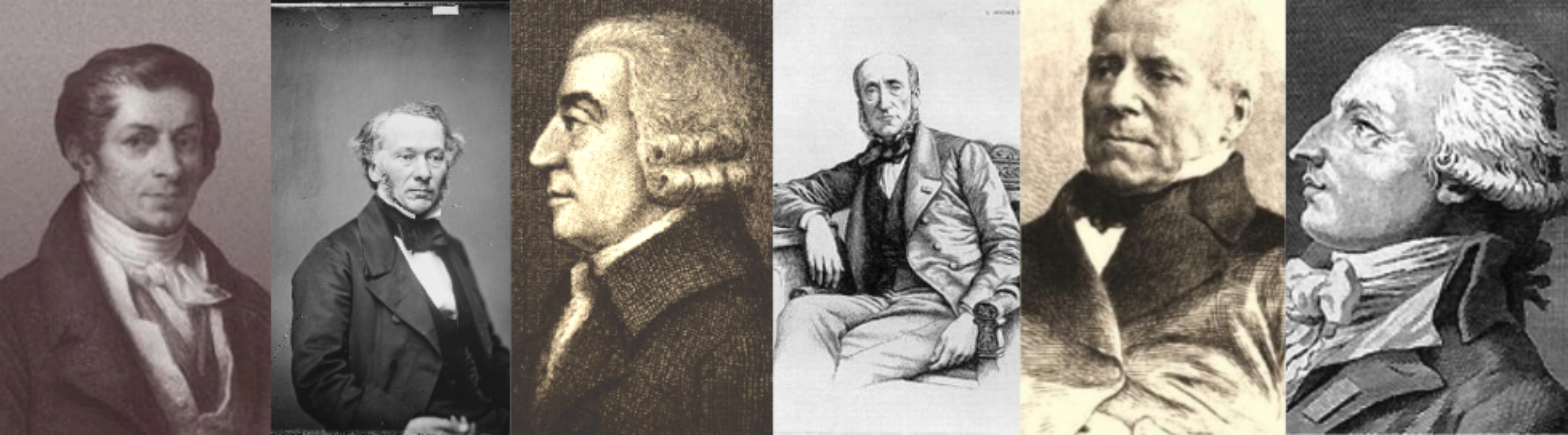

The course begins with a detailed introduction to Bastiat's life and historical context, before examining the thinkers who marked his thought, such as Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, Antoine Destutt de Tracy, Charles Comte, Charles Dunoyer, and Richard Cobden. Then, the course looks at Bastiat's opponents, including Rousseau, classical education, protectionism, socialism, and Proudhon.

An important part of the course is dedicated to the economic sophisms denounced by Bastiat, such as "What is seen and what is not seen," "The petition of the candlemakers," plunder through taxation, and the distinction between the two economic morals. The course also addresses the economic harmonies advocated by Bastiat, including the miracle of the market, the power of responsibility, and true solidarity.

Finally, the course concludes with a reflection on "The Law," addressing key concepts like the right to property, legal plunder, and the role of the state. The conclusion of the course revisits the legacy of Frédéric Bastiat and his enduring influence on modern economics.

Join Damien Theillier in this enriching exploration of Frédéric Bastiat's thought and discover how his ideas can illuminate current economic and political debates.

Introduction

Course Overview

The goal of this course is to provide you with a deep understanding of the life, intellectual influences, ideological opponents, and economic theories of Frédéric Bastiat. Through this structured journey, you will discover how his ideas have shaped economic thought and continue to influence current debates.

Section 1: Introduction

We will start with a general overview of Frédéric Bastiat, an underrated genius

of economics. You will learn about his life, intellectual journey, and the historical

context in which he developed his thinking. Understanding this context is essential

to fully grasp the scope of his writings and theories.

Section 2: Influences

We will proceed with analyzing the thinkers who shaped Frédéric Bastiat’s economic

thought. You will learn how major figures such as Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say,

Antoine Destutt de Tracy, Charles Comte, Charles Dunoyer, and Richard Cobden

contributed to his intellectual development, laying the foundations for his reflection

on free trade and market economics.

Section 3: Opponents

Next, we will explore Bastiat’s criticisms of his ideological opponents. Whether

it be Rousseau, classical education, protectionism, socialism, or Proudhon, you

will understand why Bastiat considered these doctrines as obstacles to economic

and social progress, and how he responded to their arguments with sharp logic.

Section 4: Economic Fallacies

This section is dedicated to the economic fallacies exposed by Bastiat, including

the famous "What Is Seen and What Is Not Seen" and "The Candlemakers' Petition". We will examine how he skillfully demonstrated, through satire and

rigorous analysis, the common economic errors of his time, which remain

relevant today.

Section 5: Economic Harmonies

Here, you will discover Bastiat’s positive vision of the economy. We will address

concepts such as the miracle of the market, the power of individual responsibility,

and the distinction between true and false solidarity. Bastiat viewed the economy

as a coherent system where well-understood self-interest benefits the common

good. We will explore why.

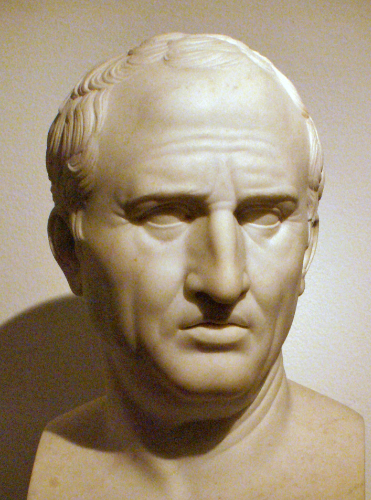

Section 6: The Law

To conclude this course, we will delve into Bastiat’s major work, "The Law", where he presents his reflections on property rights, legal plunder, and

the limited role of the state. You will understand why this essay is

considered one of the most compelling manifestos in favor of individual

freedom and market economy.

Ready to discover how Frédéric Bastiat’s ideas still resonate today? Join us on this intellectual journey that could challenge your understanding of economics!

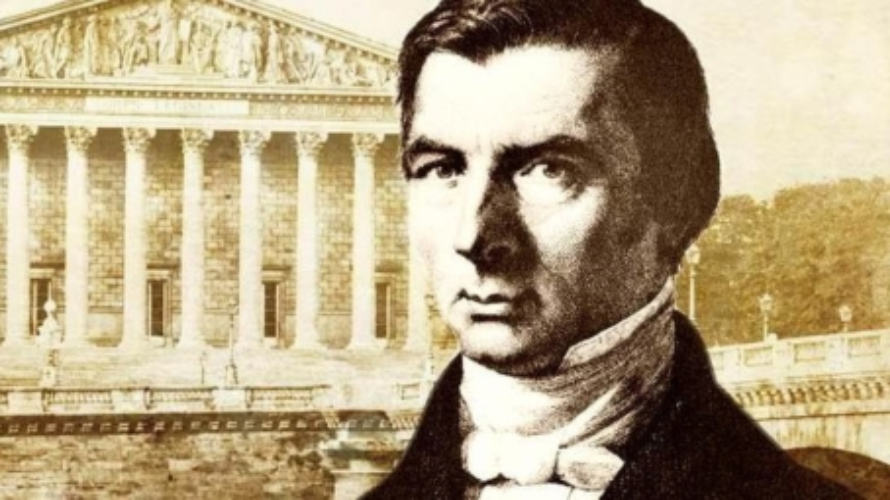

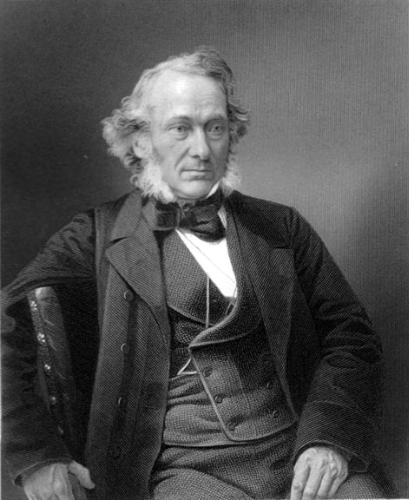

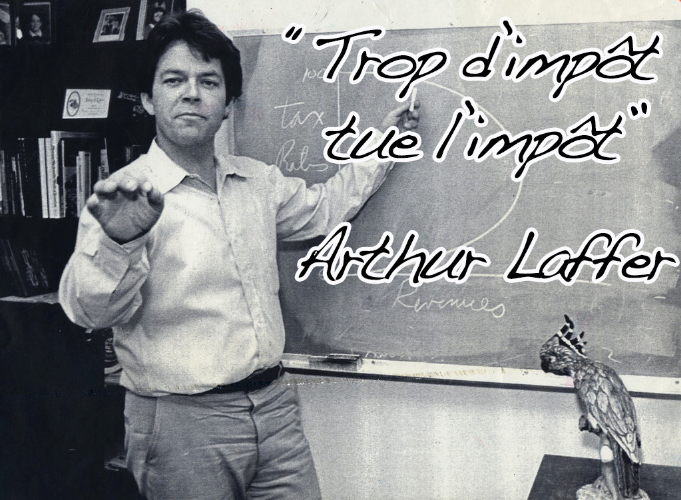

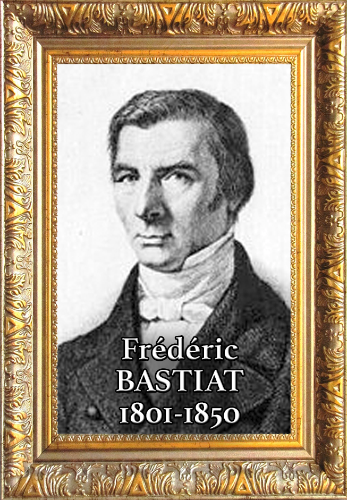

Bastiat: An Underrated Genius

This course is an introduction to Frédéric Bastiat, an unrecognized genius

and a beacon for our times. In this brief introduction, I will try to help

you discover who Frédéric Bastiat was and what are the major themes we will

cover during this series.

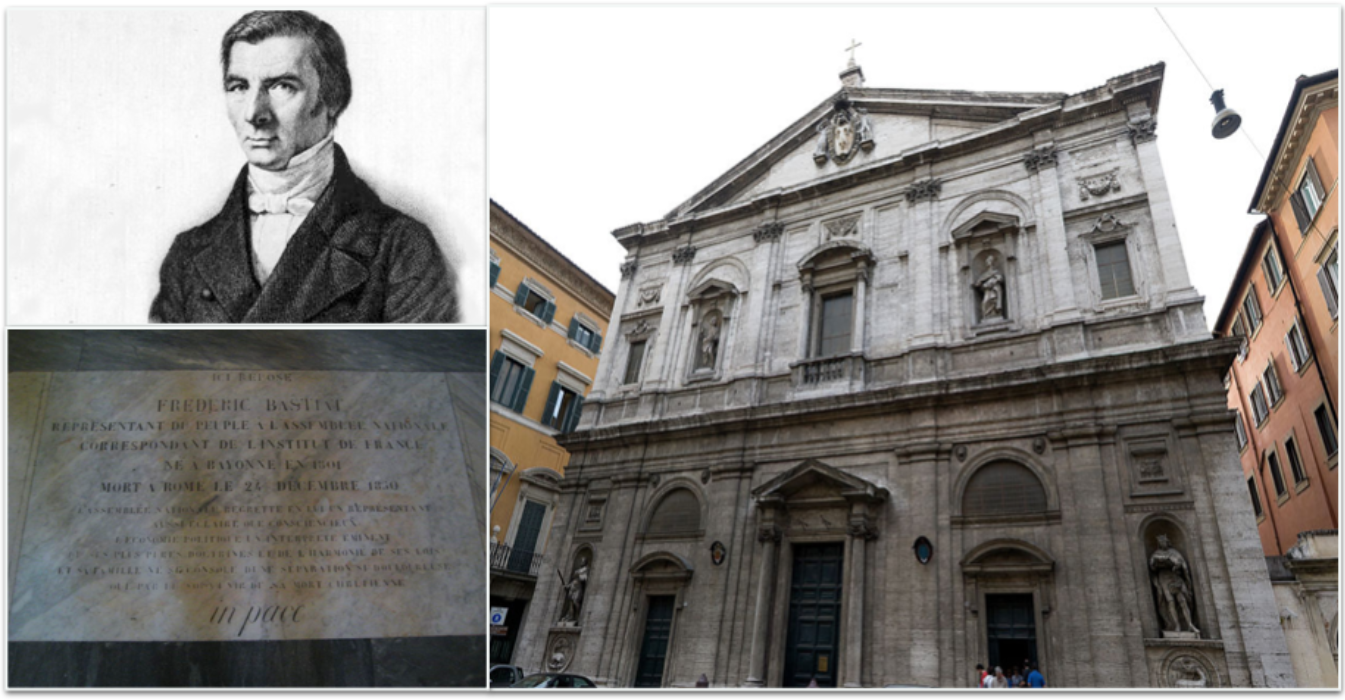

Indeed, Frédéric Bastiat, who was born in 1801 and lived during the first half of the 19th century, remained for some time an important author. And then, gradually, he disappeared and today, no one hears about him, no one knows who he is. Yet, paradoxically, this author has been translated into many languages, including Italian, Russian, Spanish, and English.

It turns out that after World War II, one of his books was published in the United States. It became very famous, to the point that Ronald Reagan himself said it was his favorite book, and this little book is called "The Law." Bastiat is thus one of the two most famous French authors in the United States, the other being well known in France too, Alexis de Tocqueville.

(Market place in Mugron in the Landes, the town of Bastiat)

(Market place in Mugron in the Landes, the town of Bastiat)

So, an unrecognized genius but also a light for our times. Indeed, Frédéric Bastiat, who was born in Bayonne, first lived part of his life in the Landes where he managed an agricultural estate he had inherited and he led a life ultimately as an entrepreneur. And then, very early on, he became interested in economics, he traveled to England, he met Richard Cobden who was a leader of the free trade movement. Bastiat was fascinated by this movement, he was convinced that free trade was a solution for France and he decided thereafter to try to spread his ideas in France. He wrote articles that were very successful and he moved to Paris to run a newspaper called at the time the Journal des économistes.

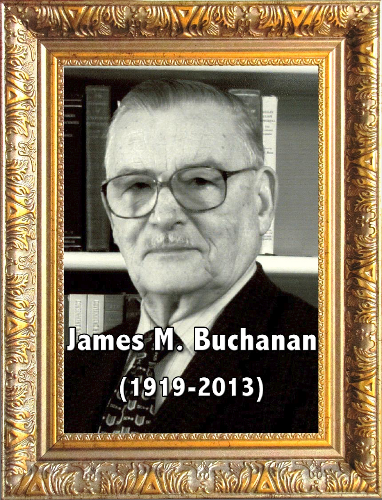

He was also a philosopher and a thinker about society, social order, justice, law, a thinker of rights. And in that regard, we can say that Bastiat is a light for our times. And I would like to conclude with that. He is someone who tried to understand the workings of the political market. Of course, he is also a defender of the market economy, for whom ultimately the market economy is the best way to create wealth. But besides that, and this is where he is unrecognized, he understood the mechanisms of the political market.

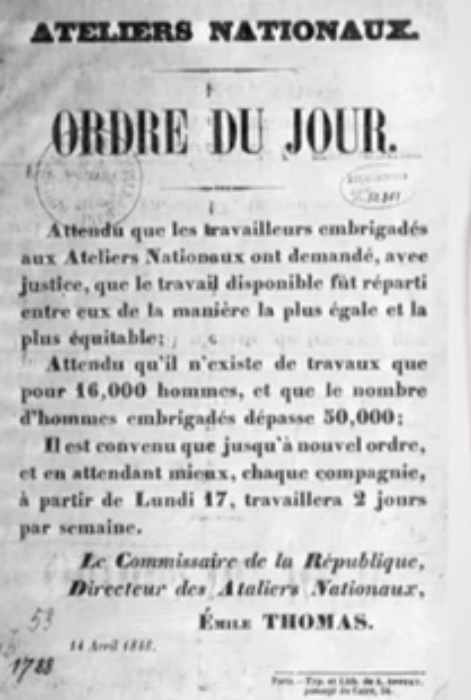

When he was elected as a deputy, it was during the Second Republic, and from that point forward, it was the people who made the laws. At that time, Bastiat witnessed a sort of inflation of laws in all directions, including the creation of public services, social rights, taxes, etc.

NATIONAL WORKSHOPS

AGENDA. Whereas the workers enrolled in the National Workshops have justly requested that the available work be distributed among them as equally and fairly as possible;

Whereas work exists only for 16,000 men, and the number of enrolled men exceeds 50,000;

It is agreed that, until further notice and pending better arrangements, each company shall work two days per week starting Monday the 17th.

The Commissioner of the Republic, Director of the National Workshops,

Émile THOMAS.

And he realized that fundamentally, nothing had really changed. People disposed of others' property through voting and the law, what he called legal plunder. This phenomenon of legal plunder was at the center of his work, especially in this short text he wrote towards the end of his life, "The Law," where he contrasts legal plunder with property, the right to property. He shows that, fundamentally, the real solution to the social problem is freedom, that is, property, the control over oneself and the fruits of one's labor.

In this course, we will travel together through the thought of Frédéric Bastiat, starting from the influences of the authors who shaped him very early on in his youth, then we will look into his economic sophisms, and finally, we will conclude with this great text, "The Law," which will introduce us to the analysis of the political market, to the analysis of society.

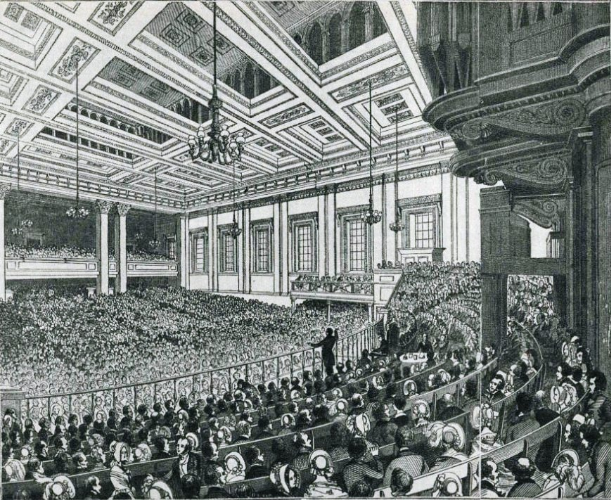

The Life and Historical Context

In 1844, Frédéric Bastiat made a business trip to Spain. After staying in Madrid, Seville, Cadiz, and Lisbon, he decided to embark for Southampton, and to visit England. In London, he had the opportunity to attend meetings of the Anti-Corn Law League, whose work he had followed from a distance. He met the main leaders of this Association, including Richard Cobden, who would become his friend.

It was there that the course of his life would radically change. He himself recounts that his vocation as an economist was decided at that moment. Upon returning to France, he had only one idea in mind: to make France aware of the liberal movement stirring England. Frédéric Bastiat was born in Bayonne on June 30, 1801. Orphaned at the age of 9, he pursued his studies at the Catholic college of Sorèze. He was gifted in languages, learning English, Spanish, and even Basque. However, he was not motivated by his studies and decided against taking the Baccalaureate, choosing instead to work in his uncle's import-export business in Bayonne.

In 1825, he inherited an agricultural estate from his grandfather, which he managed as a "gentleman-farmer," in his own words. It was then that he encountered firsthand the problems caused by the lack of a clear definition of property rights. He decided to become a justice of the peace in his town of Mugron, in the heart of the Landes, a commercial and fluvial crossroads between the ports of Bordeaux and Bayonne. Later, he was elected as a member of the General Council of the Landes.

He quickly developed a passion for political economy and studied the works of Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, Destutt de Tracy, Charles Dunoyer, and Charles Comte. He read English newspapers, and it was there that he learned about the existence of an English league for free trade.

(Say, Cobden, Smith, Chevalier, Dunoyer, Destutt de Tracy)

(Say, Cobden, Smith, Chevalier, Dunoyer, Destutt de Tracy)

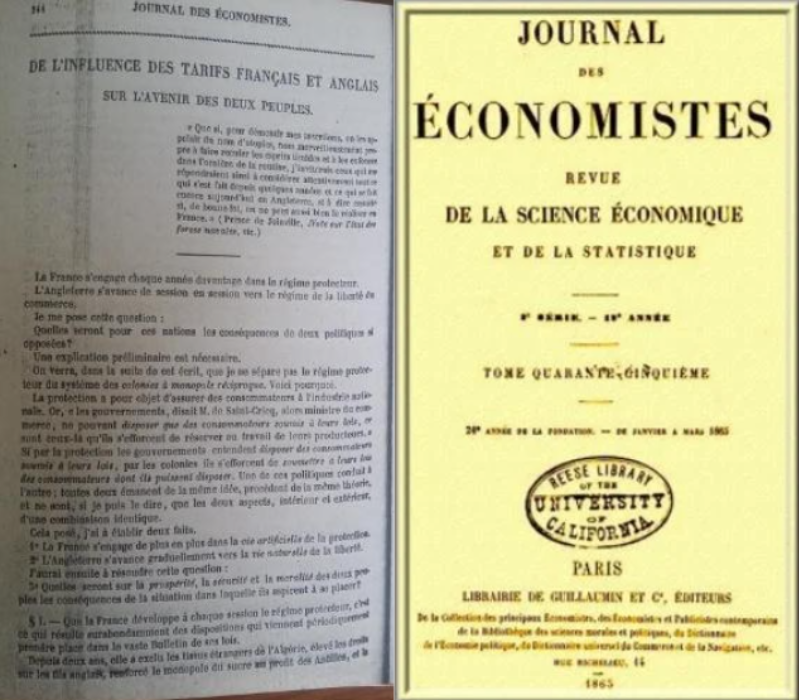

Upon his return from England, he wrote an article titled: "On the Influence of English and French Tariffs on the Future of the Two Peoples," which he sent to the Journal des Économistes in Paris. The article appeared in the October 1844 issue, and it was a complete success. Everyone admired his powerful and incisive argumentation, his sober and elegant style.

The Journal des Économistes then asked him for more articles, and several members of the Political Economy Society, notably Horace Say, the son of Jean-Baptiste Say, and Michel Chevalier, a renowned professor, congratulated him, encouraging him to continue with them in the work of spreading economic truths. This marked the beginning of a new life in Paris.

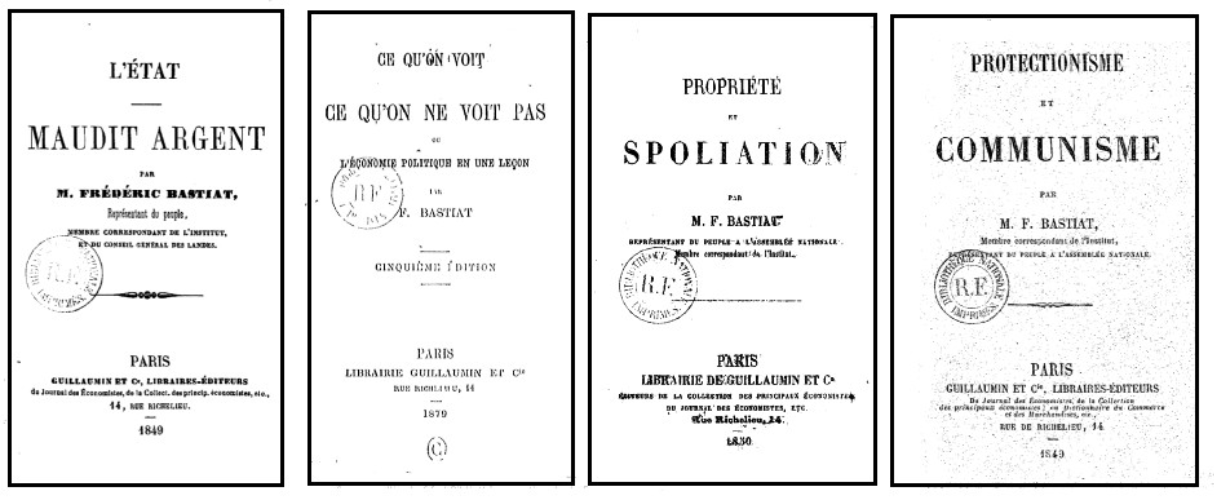

He first published the initial series of Economic Sophisms, in which he attacked protectionists with boldness and irony. In Paris, he even started a course on political economy in a private room, eagerly attended by the student elite.

The following year, he founded the "Association for Free Trade" in France

and threw himself into the fight against protectionism in France. He raised

funds, created a weekly review, and gave lectures throughout the country.

The first meeting took place in Bordeaux on February 23, 1846, during which

the Bordeaux Association for Free Trade was established. Soon, the movement

spread throughout France. In Paris, an initial core was formed among the

members of the Society of Economists, to which deputies, industrialists, and

traders joined. Significant groups also formed in Marseille, Lyon, and Le

Havre.

The February Revolution of 1848 overthrew the monarchy of Louis-Philippe, known as the July Monarchy (1830-1848), and saw the advent of the Second Republic. Bastiat was then elected as a member of the legislative assembly as a deputy for Landes. He sat in the center-left, with Alexis de Tocqueville, between the monarchists and the socialists. There, he endeavored to defend individual liberties such as civil liberties and opposed all restrictive policies, whether they came from the right or the left. He was elected vice-president of the Finance Committee and constantly endeavored to remind his fellow deputies of this simple truth, often forgotten in parliaments:

One cannot give to some, by law, without being obliged to take from others by another law.

Almost all of his books and essays were written during the last six years of his life, from 1844 to 1850. In 1850, Bastiat wrote two of his most famous works: The Law and a series of pamphlets titled What is Seen and What is Not Seen. The Law has been translated into many foreign languages, including English, German, Spanish, Russian, and Italian.

He died in Rome in 1850, from tuberculosis. He is buried at the Saint Louis des Français Church in Rome.

Influences

Adam Smith and Jean-Baptiste Say

In economics, Bastiat always acknowledged his debt to Adam Smith and Jean-Baptiste Say. At 26, he wrote to one of his friends, "I have never read on these subjects but these four works, Smith, Say, Destutt, and the Censor."

(Jean-Baptiste Say and Adam Smith)

(Jean-Baptiste Say and Adam Smith)

Political economy, as conceived by Adam Smith and J.-B. Say, is encapsulated in a single word: freedom. Freedom of trade, individual freedom, free trade, and free initiative. Free trade was first defended by the physiocrats, such as François Quesnay and Vincent de Gournay, and then by Adam Smith who synthesized their ideas with his own observations. Finally, at the end of the 18th century, Jean-Baptiste Say clarified and corrected some points of his master Adam Smith's doctrine in his masterful Treatise on Political Economy.

(Say, Destutt de Tracy, Quesnay, de Gournay)

(Say, Destutt de Tracy, Quesnay, de Gournay)

Adam Smith was interested in prosperity, not as an end in itself but as a means for the moral elevation of individuals. For him, the wealth of nations consists of the wealth of individuals. If you want a prosperous nation, says Adam Smith, let individuals act freely. And the market works because it allows everyone to express their preferences and pursue their interest.

The great novelty of modern economists at the dawn of the 18th century is that they are interested in each individual with the will to restore their capacity for action while thinking about how to contain passions and conflicts. Man naturally wants to improve his lot and that of his loved ones through the exchange of goods and services.

What Adam Smith shows is that one can only serve one's own interest by serving the interest of others:

Give me what I need, and you will have from me what you need yourselves. (...) It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.

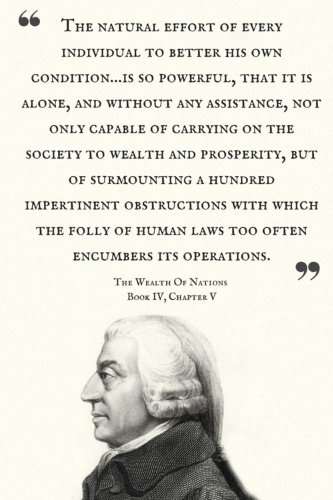

“The natural effort of every individual to better his own condition... is so powerful, that it is alone, and without any assistance, not only capable of carrying on the society to wealth and prosperity, but of surmounting a hundred impertinent obstructions with which the folly of human laws too often encumbers its operations.”

The Wealth of Nations

Book IV, Chapter V

Exchange is a positive-sum game. What one gains, the other also gains. It thus differs from political redistribution where there is always a winner and a loser. If we consider the English school, for Smith, for Ricardo, and for Locke before them, value is linked to labor. For Marx, it is the same.

(Marx, Ricardo, Smith, Locke)

(Marx, Ricardo, Smith, Locke)

On the other hand, Bastiat will admit with Jean-Baptiste Say that utility is the true foundation of value. Labor does not create value. Scarcity does not either. Everything stems from utility. Indeed, no one agrees to pay for a service unless they deem it useful. One only ever produces utility. But Bastiat also nuanced Say on this point. It's not about the utility that is in things, it's about the relative utility of services. "Value is the ratio of two exchanged services," according to his own words. Therefore, value is subjective, and the only way to grasp individuals' preferences is to observe their behavior in a free market. The market reveals individual preferences and is the great regulator of society through exchange.

The economy obeys a number of simple laws derived from human behavior. One of them, called "Say's Law," is as follows: "Products and services are exchanged for products and services." His idea is that nations and individuals benefit from an increase in production level because it offers increased opportunities for mutually beneficial exchanges.

Indeed, products are only purchased in anticipation of the services the buyer expects: I buy a disk for the music I will listen to, I buy a movie ticket for the film I will see. And in an exchange, each party decides because it judges that it can derive more services from what it acquires than what it gives up. In this context, money is just an intermediary commodity, it compensates for a service rendered and opens up other services.

For Bastiat, the economy of exchanges, that is, of mutual services freely offered and accepted, is what underpins peace and prosperity, allowing for the harmony of interests.

But from Jean-Baptiste Say, Frédéric Bastiat also inherits a key concept, that of plunder. For, he says, echoing the words of Say:

There are only two ways to acquire the things necessary for the preservation, embellishment, and improvement of life: production and plunder.

Producers resort to persuasion, negotiation, and contract, while plunderers resort to force and deceit. It is therefore up to the law to suppress plunder and to secure labor as well as property. As Adam Smith had already stated, ensuring the safety of citizens is the main mission of public authority, and it is this that legitimizes the levying of taxes.

Antoine Destutt de Tracy

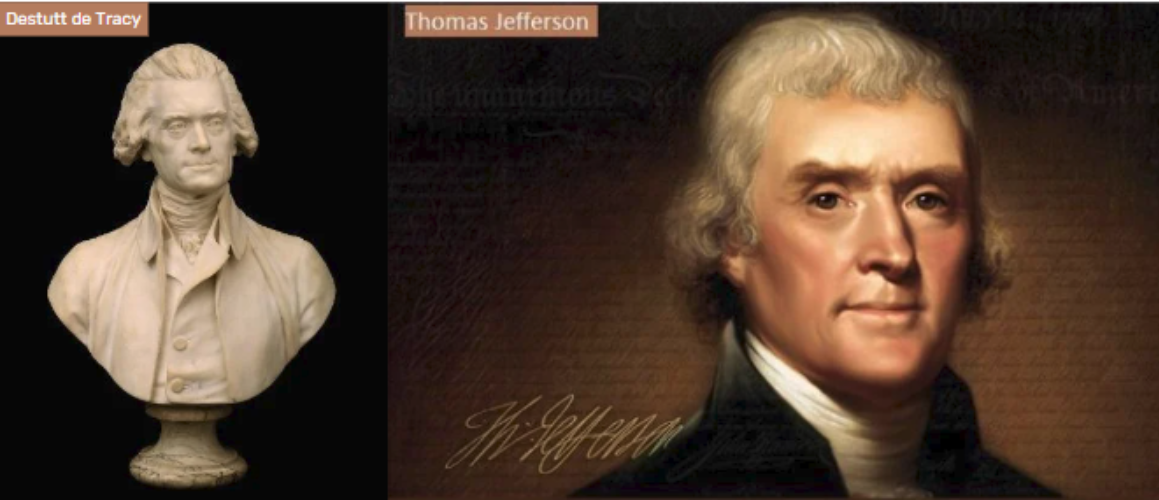

It is little known, but Destutt de Tracy had a decisive influence on the future President of the United States, Thomas Jefferson, while he was ambassador to Paris in the 1780s.

For every man, his first country is his homeland, and the second is France" & "Tyranny is when the people fear their government; liberty is when the government fears the people.

Thomas Jefferson

Indeed, his Treatise on Political Economy condemned protectionism and Napoleonic expansion. It was therefore banned from publication in France by Bonaparte. However, it was translated into English and published in the United States by Jefferson himself. He made this text the first political economy textbook of the University of Virginia, which he had just founded in Charlottesville. The Treatise was not published in France until 1819!

Destutt de Tracy, a philosopher and economist, was the leader of the so-called "Ideologues" school, which included people like Cabanis, Condorcet, Constant, Daunou, Say, and Germaine de Staël. They are the heirs of the Physiocrats and the direct disciples of Turgot.

By ideology, Tracy simply meant the science that deals with the study of ideas, their origin, their laws, their relationship with language, that is, in more contemporary terms, epistemology. The term "ideology" did not have the pejorative connotation that Marx would later give it to discredit the economists of "laissez-faire". The journal of the ideologue movement was called La Décade philosophique et littéraire.

It dominated the revolutionary period and was directed by Jean-Baptiste Say. Destutt de Tracy was elected a member of the French Academy in 1808 and of the Academy of Moral and Political Sciences in 1832. His daughter married Georges Washington de La Fayette (the son of the first American president) in 1802, which shows the close proximity that still existed between France and young America at that time.

The purpose of his Treatise on Political Economy is to "examine the best way

to employ all our physical and intellectual faculties to satisfy our various

needs." His idea is that trade is the source of all human good; it is the civilizing,

rationalizing, and pacifying force of the world. The great maxim of political

economy is formulated by him as follows: "trade is the whole of society, just

as labor is the whole of wealth." Indeed, he sees society as "a continuous series

of exchanges in which both contractors always gain." Therefore, the market is

the opposite of predation. It enriches some without impoverishing others. As

it will be said later, it is not a "zero-sum game," but a positive-sum game.

The purpose of his Treatise on Political Economy is to "examine the best way

to employ all our physical and intellectual faculties to satisfy our various

needs." His idea is that trade is the source of all human good; it is the civilizing,

rationalizing, and pacifying force of the world. The great maxim of political

economy is formulated by him as follows: "trade is the whole of society, just

as labor is the whole of wealth." Indeed, he sees society as "a continuous series

of exchanges in which both contractors always gain." Therefore, the market is

the opposite of predation. It enriches some without impoverishing others. As

it will be said later, it is not a "zero-sum game," but a positive-sum game.

Our author does not go as far as to define political economy as the science of exchanges. But this same reasoning will be taken up and carried through by Bastiat. Selling is an exchange of objects, renting is an exchange of services, and lending is merely a deferred exchange. Political economy thus becomes for Bastiat "the theory of exchange."

According to Destutt de Tracy, property necessarily stems from our nature, from our faculty of desire. If man wanted nothing, he would have neither rights nor duties. To meet his needs and fulfill his duties, man must employ means that he acquires through his labor. And the form of social organization that conforms to this end is private property. That is why the sole object of government is to protect property and to allow peaceful exchange.

For him, the best taxes are the most moderate ones, and he wishes that the state's expenditures be as restricted as possible. He condemns the plundering of society's wealth by the government in the form of public debt, taxes, banking monopolies, and expenditures. Once again, the law should only serve to protect freedom; it should never plunder.

Finally, he adds this recommendation, which has not lost its relevance:

Let the government not make and not be able to make debts that commit future generations and always lead states to their ruin.

In conclusion, the Ideologues had a profound intuition, namely that production and exchanges are the real solution to political problems and the true alternative to wars. Wars are always predatory, whether they are internal, like during the Revolution, or external, like those waged by the ancient kings and by Napoleon.

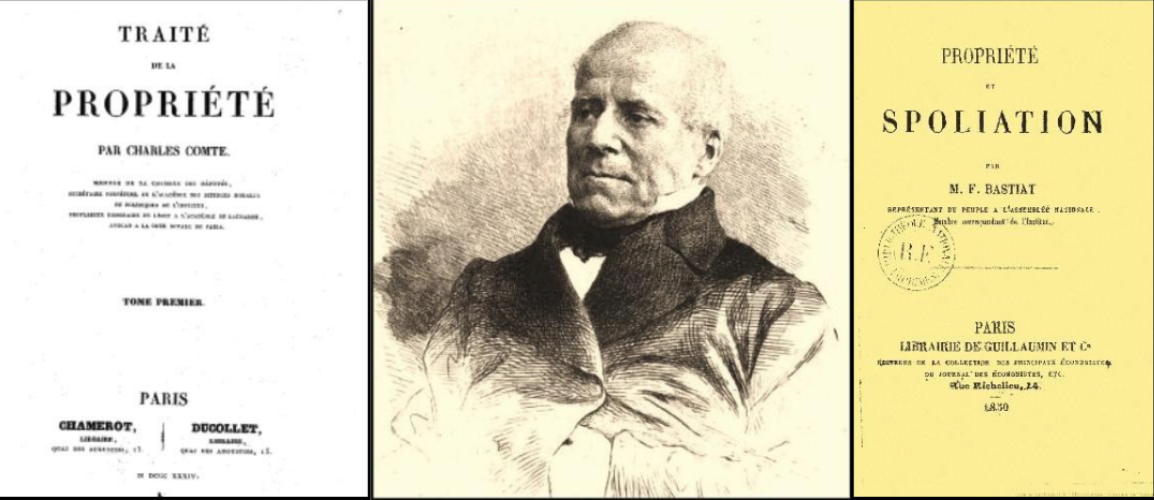

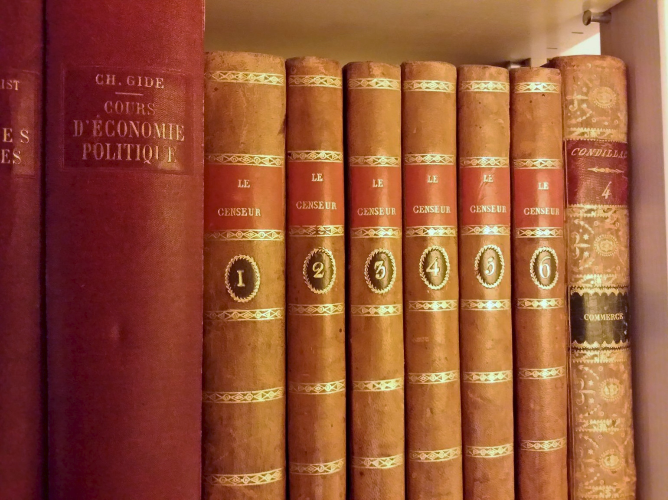

Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer

The history of all civilizations is the story of the struggle between the plundering classes and the productive classes. This is the creed of the two authors we are going to discuss. They are the originators of a liberal theory of class struggle that inspired Frédéric Bastiat as much as Karl Marx, although the latter distorted it.

For Comte and Dunoyer, plunder, meaning all forms of violence exercised in society by the strong over the weak, is the great key to understanding human history. It is at the origin of all phenomena of exploitation of one class by another.

If Frédéric Bastiat owes his economic education to Smith, Destutt de Tracy, and Say, he owes his political education to the leaders of the journal Le Censeur, Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer.

This review (1814-1819), renamed Le Censeur européen after the Hundred Days, disseminated the liberal ideas that triumphed in 1830 with the insurrection of the Three Glorious Days and the rise to power of the Duke of Orléans, Louis-Philippe I.

Charles Comte, cousin of Auguste Comte and son-in-law of Say, is the founder of the review. He was soon joined by Charles Dunoyer, a jurist like himself, and then by a young historian, Augustin Thierry, former secretary of Saint Simon. Their motto on the front page of each issue of the review was "Peace and Liberty".

What is the goal of the review? The title speaks for itself: to censor the government. To fight against the arbitrariness of power by enlightening public opinion, to defend the freedom of the press.

(Benjamin Constant)

(Benjamin Constant)

They adopt from Benjamin Constant the distinction between the Ancients and the Moderns, characterized on one hand by war, and on the other by commerce and industry. But they add with Say that political economy provides the best explanation of social phenomena. They particularly understand that nations achieve peace and prosperity when property rights and free trade are respected. From now on, for them, political economy is the true and only foundation of politics. To philosophy, which confines itself to the abstract critique of forms of government, must be substituted a theory based on the knowledge of economic interests.

Political economy, by demonstrating how peoples prosper and decline, has laid the true foundations of politics.

Dunoyer

This new social theory contains one of the elements that would become the cornerstone of Marx and Engels' scientific socialism: class struggle. But what does the liberal theory of class struggle consist of, and how does it differ from Marxism?

It starts with the individual who acts to meet their needs and desires. From the moment one creates, that is, increases the utility of things, enhancing their value, one engages in industry. Here, an industrialist is not an industry owner, as current language might suggest, but a producer, regardless of the field in which they work. That's why their theory is called industrialism. It posits that the goal of society is the creation of utility in the broad sense, that is, goods and services useful to humans.

On this point, individuals face two fundamental alternatives: they can plunder the wealth produced by others, or they can work to produce wealth themselves. In any society, one can clearly distinguish those who live off plunder from those who live off production. Under the Ancien Régime, the nobility directly attacked the most industrious to live off a new form of tribute: tax. The rapacious nobility was succeeded by hordes of bureaucrats, no less rapacious.

While for Marx, class antagonism is situated within the productive activity itself, between employees and employers, for Comte and Dunoyer, the conflicting classes are, on one side, the society's producers, who pay taxes (including capitalists, workers, peasants, scholars, etc.) and on the other, the non-producers, who live off rents financed by taxes, "the idle and devouring class" (bureaucrats, officials, politicians, beneficiaries of subsidies or protections).

Then, unlike Marx, the authors of the Censeur Européen do not advocate for class warfare. Instead, they campaign for social peace. And this, according to them, can only be achieved through the depoliticization of society. To this end, it is important to first reduce the prestige and benefits of public offices. It is then important to give influence in the political body to the producers.

Finally, the only way to rid the world of the exploitation of one class by another

is to destroy the very mechanism that makes this exploitation possible: the power

of the State to distribute and control property and the allocation of benefits

related to it (the "positions").

Finally, the only way to rid the world of the exploitation of one class by another

is to destroy the very mechanism that makes this exploitation possible: the power

of the State to distribute and control property and the allocation of benefits

related to it (the "positions").

Their ideas, profoundly innovative, would forever mark Frédéric Bastiat, who would himself become a deep thinker on political crises.

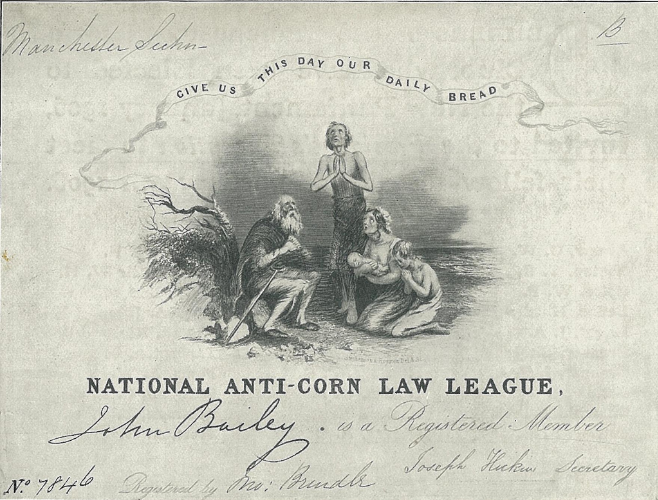

Cobden and the League

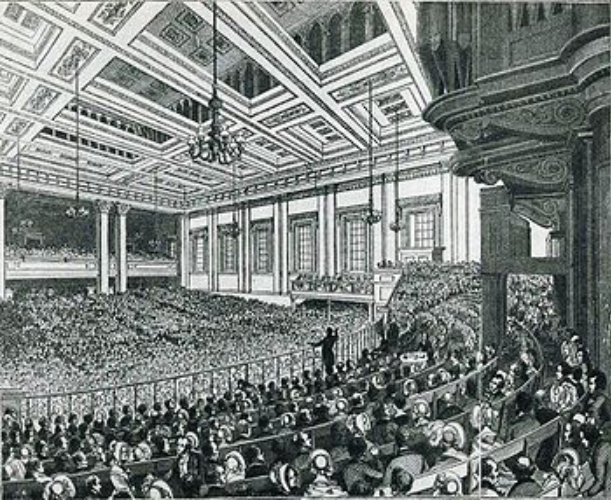

It is 1838, in Manchester, a small number of men, little known until then, gather to find a way to overthrow the monopoly of the wheat landowners through legal means and to accomplish, as Bastiat would later recount,

Without bloodshed, by the sole power of opinion, a revolution as profound, perhaps more profound than that which our fathers carried out in 1789.

From this meeting would emerge the League against the corn laws, or the grain laws, as Bastiat would call them. But very quickly, this goal would become that of the total and unilateral abolition of protectionism.

This economic battle for free trade would occupy all of England until 1846. In France, outside of a small number of initiates, the existence of this vast movement was completely unknown. It was by reading an English newspaper, to which he had subscribed by chance, that Frédéric Bastiat learned of the League's existence in 1843. Enthused, he translated the speeches of Cobden, Fox, and Bright. Then he corresponded with Cobden and finally, in 1845, he went to London to attend the League's gigantic meetings.

It was this campaign of agitation for free trade, throughout the kingdom, with tens of thousands of members, that set Bastiat's pen on fire and radically and definitively changed the course of his life.

The League can be compared to a traveling university, educating economically those who attended its meetings across the country—common folk, industrialists, cultivators, and farmers, all of whom the League had taken under its wing and whose interests the grain laws oppressed. Richard Cobden was the soul of the movement and an outstanding agitator.

A fascinating and formidable speaker, he had a prodigious gift for inventing striking and concise phrases, far from the abstract discourses of economists.

What is the bread monopoly? he exclaimed. It's the scarcity of bread. You are surprised to learn that the legislation of this country, on this matter, has no other purpose than to produce the greatest possible scarcity of bread. And yet it is nothing else. The legislation can only achieve its goal through scarcity.

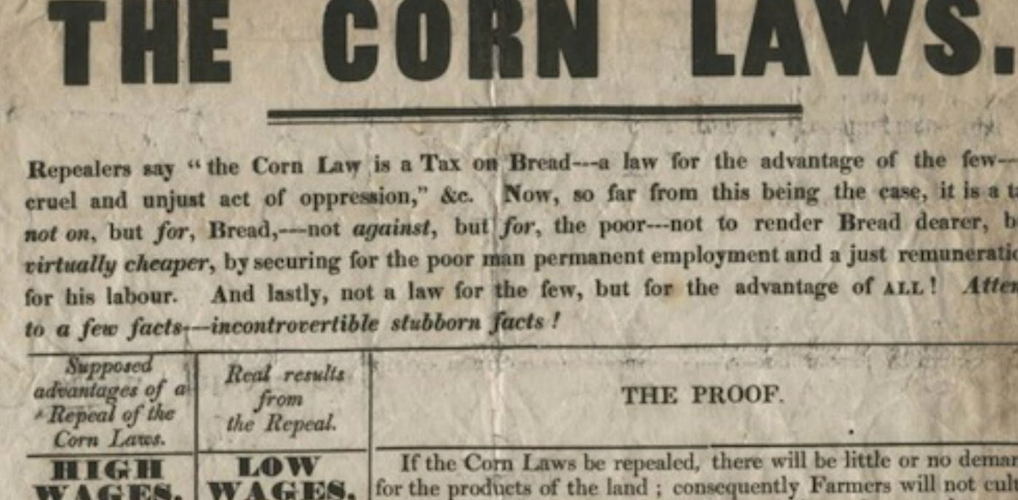

In 1845, Bastiat published in Paris his book Cobden and the League, with his translations accompanied by comments. The book opens with an introduction on the economic situation of England, on the history of the origin and progress of the League. Since 1815, protectionism was very developed in England. There were, in particular, laws limiting grain imports which had very harsh consequences for the people. Indeed, wheat was necessary for making bread, a vital commodity at the time. Moreover, this system favored the aristocracy, that is, the large landowners, who derived rents from it.

What coexists in England, Bastiat wrote, is a small number of plunderers and a large number of plundered, and one does not need to be a great economist to conclude the opulence of the former and the misery of the latter.

The goal of the League was to mobilize public opinion to pressure parliament to repeal the grain law. In the long term, Cobden and his friends hoped to:

- Increase industrial outlets

- Increase employment

- Reduce the price of bread

- Make agriculture and industry more efficient through competition

- Promote peace among nations

(Jeremy Bentham)

(Jeremy Bentham)

A disciple of Bentham's utilitarianism, Cobden's conviction was that the freedom of labor and trade directly served the interest of the most numerous, poorest, and most suffering masses of society. On the contrary, customs as an instrument of arbitrary prohibitions and privileges could only benefit certain most powerful industries.

In the 1841 elections, five members of the league, including Cobden, were

elected to parliament. On May 26, 1846, unilateral free trade became the law

of the kingdom. From then on, the United Kingdom would experience a

brilliant period of freedom and prosperity. What's interesting is that

Bastiat appropriated a part of their method; he assimilated their language

and transposed it into the French context. The book on Cobden and the League

quickly became a success, and Bastiat made a sensational entry into the

world of economists. He founded an association in Bordeaux in favor of free

trade and then moved it to Paris. He was offered the leadership of the

Journal des Économistes. The movement was born, and it continued until 1848.

It was only after Bastiat's death, in 1866, that Napoleon III would sign a free trade treaty with England, a sort of posthumous victory for the man who had dedicated the last six years of his short life to this great idea.

(Michel Chevalier)

(Michel Chevalier)

The question of free trade continues to be relevant today. Geography textbooks in schools claim that globalization is to blame and that poor countries need Western aid to get by. Yet, extreme poverty has been halved in 20 years. By choosing openness, countries like India, China, or Taiwan have been able to escape poverty, while stagnation characterizes closed countries like North Korea or Venezuela. According to the UN, 36% of humanity lived in total destitution in 1990. They are now "only" 18% in 2010. Extreme poverty remains a major challenge, but it is receding.

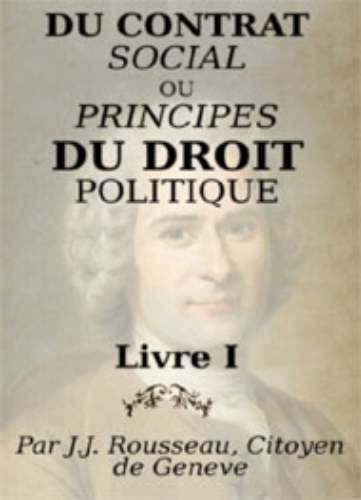

The Opponents

Rousseau

Frédéric Bastiat, who expressed himself in the 1840s, is the heir to a generation of Enlightenment philosophers who fought against censorship and for the freedom to debate. Think of Montesquieu, Diderot, Voltaire, Condorcet, but also Rousseau.

For them, the idea was simple: the more ideas are allowed to be expressed, the more truth progresses and the more easily errors are refuted. Science always progresses in this way.

(Montesquieu, Diderot, Voltaire, Condorcet, Rousseau)

(Montesquieu, Diderot, Voltaire, Condorcet, Rousseau)

On the contrary, few have understood that what was true for ideas was also true for goods and services. The freedom to trade with others indeed has two virtues: being efficient and leading to a fairer distribution. Not only did Rousseau not understand this, but he also fought against this freedom in the name of a false idea of law and right. One of the major sources of socialism, Bastiat notes, is Rousseau's opinion that the entire social order stems from the law.

Bastiat indeed considers Rousseau to be the true precursor of socialism and collectivism. In the author of The Social Contract, there's a phrase that quite well summarizes his philosophy: "we only begin to become men after having been citizens."

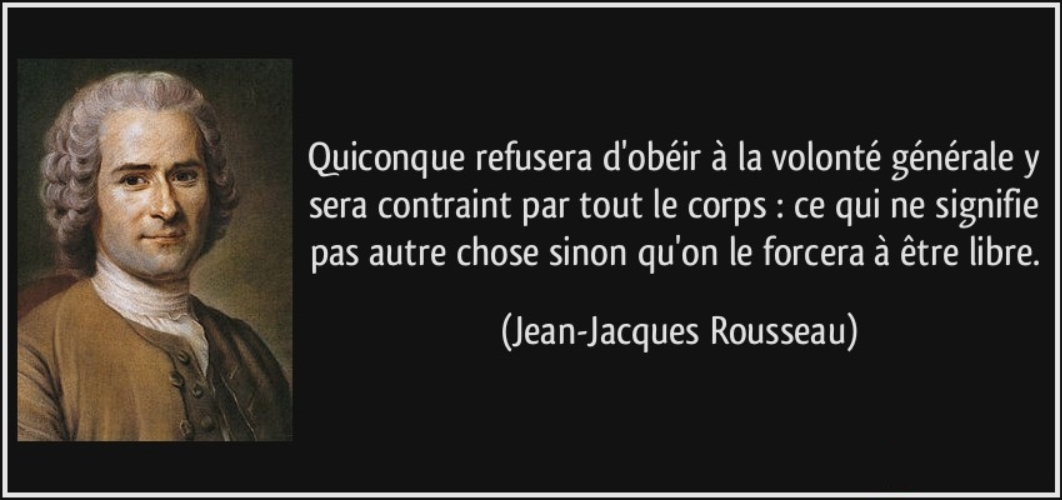

Initially, man is merely a bourgeois. But the bourgeois is a calculator; he wants his immediate pleasure, he is enslaved to his senses, to his desires, to his particular interest. In short, he is not rational, therefore he is not free. He needs to be educated, to understand that his true interest is the general interest. This is why Rousseau wrote in The Social Contract:

Whoever refuses to obey the general will shall be compelled to do so by the entire body: which means nothing else than that he will be forced to be free.

(Jean-Jacques Rousseau)

According to this doctrine, man has two wills within him: a will that tends towards personal interest, that of the bourgeois, and a will that tends towards the general interest, that of the citizen. Leading men, even by force, to want a rational end, the general interest, is leading men to become free. What they truly want is a rational end, even if they do not know it.

It is therefore perfectly legitimate, according to Rousseau, to constrain men in the name of an end that they themselves, had they been more enlightened, would have pursued, but which they do not pursue because they are blind, ignorant, or corrupt. Society is founded to force them to do what they should spontaneously desire if they were enlightened. And by doing so, one does not do violence to them since one leads them to be "free," that is, to make the right choices, choices that are in line with their true self.

Convinced that the good society is a creation of the law, Rousseau thus grants unlimited power to the legislator. It is up to him to transform individuals into accomplished men, into citizens. But, it is also up to the law to make property exist. According to Rousseau, property can only be legitimate if it is regulated by the legislator. Indeed, the evil lies in inequality and servitude, both of which stem from property. It is an invention of the strong that has led to bad society, to bourgeois society, to relations of domination. In his Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality, he writes this famous passage:

The first person who, having fenced in a piece of land, said: This is mine, and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society. How many crimes, wars, murders, how much misery and horror would have been spared the human race by the one who, pulling up the stakes or filling in the ditch, had cried out to his fellows: "Beware of listening to this impostor; you are lost if you forget that the fruits belong to all and the earth belongs to no one!"

Therefore, natural property is the source of evil. And Marx, a great reader of Rousseau, would remember this. How to combat this evil? Through the social contract, Rousseau replies. Indeed, the good society is one that results from a contract that stipulates the alienation of the individual with all his rights to the community. From then on, it is up to the community to grant rights to the individual through the law.

Contrary to Rousseau, Frédéric Bastiat says that "man is born a property owner." For him, property is a necessary consequence of the nature of man, of his constitution. He writes that "man is born a property owner, because he is born with needs whose satisfaction is indispensable to life, with organs and faculties whose exercise is indispensable to the satisfaction of these needs". But faculties are only the extension of the person, and property is only the extension of the faculties. In other words, it is the use of our faculties in work that legitimizes property.

According to Bastiat, society, people, and properties exist before laws, and he has this famous phrase: "It is not because there are laws that there are properties, but because there are properties that there are laws". That is why the law must be negative: it must prevent encroachment on people and their goods. Property is the raison d'être of the law and not the other way around.

Classical Education

87d9a8c9-2352-5cb2-8b93-678118a8145c On February 24, 1848, after three days of riots in Paris, King Louis-Philippe I abdicated his power. This marked the birth of the Second Republic.

Bastiat was in Paris, witnessing the events firsthand. Later, he would write:

On February 24, I, like many others, feared that the nation was not prepared to govern itself. I must admit, I dreaded the influence of Greek and Roman ideas that are imposed on us all by the academic monopoly.

This passage is surprising. What do Greek and Roman antiquity have to do with it?

Bastiat refers to Plato's Republic and his theory of the philosopher-king, but also to Sparta, which Rousseau so admired, to the Roman Empire, for which Napoleon was so nostalgic. Unfortunately, according to Bastiat, these Greek and Roman ideas are based on a false premise: the idea of the omnipotence of the legislator, of the absolute sovereignty of the law.

It's enough to open almost any book on philosophy, politics, or history at random to find this idea, rooted in our culture, that humanity is an inert matter receiving life, organization, morality, and prosperity from political power. Left to its own devices, humanity would tend towards anarchy and would only be saved from this disaster by the mysterious and omnipotent hand of the Legislator. However, Bastiat says, this idea has been long matured and prepared by centuries of classical education.

Firstly, he says, the Romans regarded property as a purely conventional fact, as an artificial creation of written law. Why? Simply, Bastiat explains, because they lived off slavery and plunder. For them, all properties were the fruit of spoilation. Therefore, they could not introduce into legislation the idea that the foundation of legitimate property was labor without destroying the foundations of their society. They indeed had an empirical definition of property, "jus utendi et abutendi" (the right to use and abuse). However, this definition only concerned the effects and not the causes, in other words, the ethical origins of property. To properly establish property, one must go back to the very constitution of man, and understand the relationship and necessary linkage that exist between needs, faculties, labor, and property. The Romans, who were slave owners, could they conceive the idea that "every man owns himself, and therefore his labor, and, consequently, the product of his labor"? Bastiat wonders.

Therefore, let us not be surprised, Bastiat concludes, to see the Roman idea that property is a conventional fact and of legal institution reemerge in the eighteenth century; that, far from the Law being a corollary of Property, it is Property that is a corollary of the Law.

Indeed, Rousseau shares this common legal idea of basing property on the law. Rousseau attributes to the law, and consequently to the people, absolute power over individuals and properties. And in this conception, which constitutes the very idea of the republic since the French Revolution, the legislator must organize society, like a social architect, like a mechanic who invents a machine from inert matter, or like a potter who shapes clay. The legislator thus places himself outside of humanity, above it, to arrange it at will, according to plans conceived by his luminous intelligence.

On the contrary, for Bastiat, the right of property is prior to the law. This is what he calls the principle of economists, as opposed to the principle of jurists. While "the principle of jurists virtually contains slavery, says Bastiat, that of economists contains freedom.

What then is freedom? It is property, the right to enjoy the fruits of one's labor, the right to work, to develop, to exercise one's faculties, as one sees fit, without the State intervening otherwise than by its protective action.

It is sad to think that our social and political philosophy has remained stuck on the idea that the solution to all our problems had to come from above, from the law, from the State. But this is explainable. These ideas are instilled every day in the youth in schools and universities, through the monopoly of education.

an example of such a monopolistic agent could be a government institution

an example of such a monopolistic agent could be a government institution

However, as Bastiat reminds us, monopoly excludes progress.

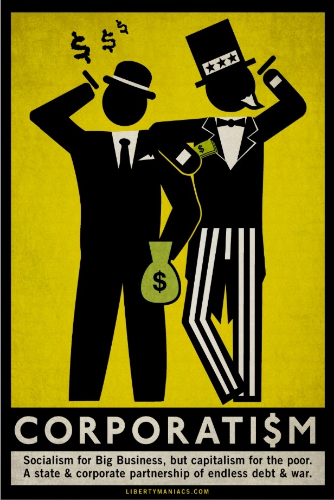

Protectionism and Socialism

(Richard Cobden)

(Richard Cobden)

As we have already seen, it was first and foremost Cobden's fight against protectionism with the English league for the abolition of the Corn Laws that led Bastiat to write articles and then books.

Protectionism is, in reality, a form of economic nationalism. It aims to eliminate foreign competition while pretending to "defend national interests." They then try to get the public authorities to accept a set of purely demagogic untruths, presented as virtuous: the defense of jobs, competitiveness, etc. Of course, elected officials yield to the pressure of producers, because it is for them a golden opportunity to consolidate their clientele and expand their power.

an example of promotional advertising of a blender produced in France

an example of promotional advertising of a blender produced in France

Our meeting with Arnaud Montebourg

Made in France,

he believes in it, we tested it

The argument for job protection is what Bastiat calls a fallacy. Because in reality, it is equivalent to a tax. It has the effect of making products more expensive. Let's take the example given by Bastiat himself.

Imagine an English knife that sells in our country for 2 euros, and a knife made in France costs € 3. If we let the consumer freely buy the knife he wants, he saves 1 euro, which he can invest elsewhere (in a book, or a pencil).

If we ban the English product, the consumer will pay one more unit for his knife. Protectionism thus results in a profit for a national industry and two losses, one for another industry (that of pencils) and the other for the consumer. On the contrary, free trade makes two happy winners.

Protectionism is also a form of class struggle. According to Bastiat, it is a system based on the selfishness and greed of producers. To increase their remuneration, farmers or industrialists demand taxes to close the market to foreign products, thus forcing consumers to pay more for their products.

Bastiat firmly sides with consumers. Against class interest, he posits the general interest, which is the interest of the consumer, that is, the interest of everyone. It is always from the consumer's point of view that the State should position itself when acting.

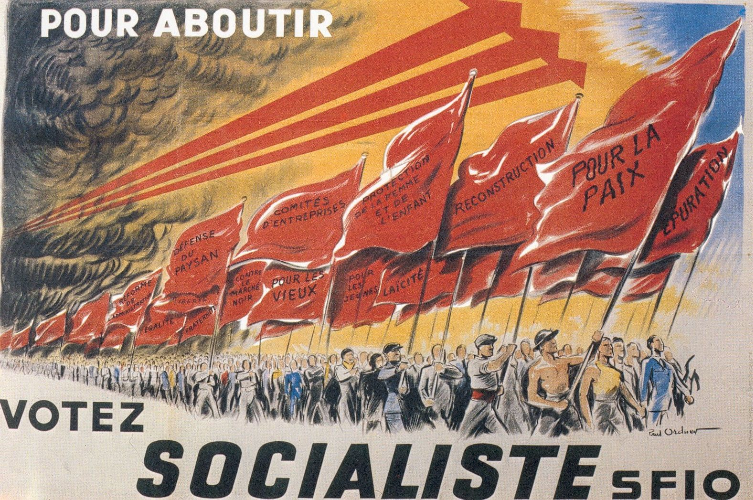

With the February 1848 revolution and its barricades, a more formidable enemy than protectionism would emerge, one with which it shares many affinities: socialism.

What is it? It's a political movement that demands the organization of labor by law, the nationalization of industries and banks, and the redistribution of wealth through taxation. Bastiat would now devote all his energy, talent, and writings against this new doctrine, which could only lead to the exponential growth of power and perpetual class struggle. Thus, from the first days of the revolution, he contributed to a short-lived newspaper named "La République Française," which quickly became known as a counter-revolutionary journal. This was the time when he wrote his pamphlets on property, the state, plunder, and the law.

On June 27, 1848, the day after a bloody new insurrection in Paris, in a lengthy letter to Richard Cobden, he dwelled on the causes that could have led to these events.

1° The first of these causes is economic ignorance. It is this that prepares minds to embrace the utopias of socialism and false republicanism. I refer to the previous video on the tendencies of classical and university education on this point.

2° The nation became enamored with the idea that fraternity and solidarity could be introduced into law. That is, it demanded that the state directly create happiness for its citizens. Here Bastiat sees the beginnings of the welfare state.

And he would continue to analyze its perverse effects thereafter. Here is one example, cited in the letter to Cobden:

By virtue of the natural inclinations of the human heart, everyone began to demand from the state, for themselves, a greater share of well-being. That is, the state or the public treasury was put to plunder. All classes demanded from the state, as if by right, the means of existence. The efforts made in this direction by the state only led to taxes and obstacles, and to the increase of misery.

- 3° Bastiat adds that in his view, protectionism was the first manifestation of this disorder. The capitalists began by asking for the law's intervention to increase their share of wealth. Inevitably, the workers wanted to do the same.

TO SUCCEED

VOTE SOCIALIST SFIO

To conclude, protectionists and socialists share a common point, according to Bastiat: what they seek from the law is not to ensure everyone the free exercise of their faculties and the fair reward for their efforts, but rather to favor the more or less complete exploitation of one class of citizens by another. With protectionism, it is the minority that exploits the majority. With socialism, it is the majority that exploits the minority. In both cases, justice is violated and the general interest is compromised. Bastiat sets them against each other.

The state is the great fiction through which everyone endeavors to live at the expense of everyone else.

Proudhon

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon is one of the major representatives of French socialism in the mid-19th century. He is especially famous for this statement: "Property is theft" in "What is Property?" in 1840.

There is something logically absurd in this assertion. For if there were no legitimately acquired property, logically there could not be an act such as theft. That's why Proudhon would later clarify that it is the actual distribution of property he considers theft, not property itself, which he describes as a revolutionary force foundational to anarchist society.

But Proudhon is an individualist anarchist. He does not see the proletariat, nor the state, as legitimate sources of power. He harshly criticizes communism and advocates for worker mutualism, a form of structured cooperative solidarity, which would rely on the voluntary pooling of resources for mutual aid. It is less known but Bastiat was not at all opposed to this idea in principle. He simply feared that the state would turn it into a de facto monopolistic public service. History would prove him right.

On the other hand, it is well known that in "The Poverty of Philosophy," Marx would violently attack Proudhon and his socialism, which he called "utopian," in favor of a so-called "scientific" socialism.

In June 1848, Proudhon was elected to the National Assembly, alongside Bastiat.

They were acquaintances and held each other in high regard. However, in 1849,

in a resounding controversy, Bastiat exchanged fourteen letters with him in the

columns of La Voix du Peuple. In this vigorous exchange, he clarified his stance

on monetary and banking issues. The dispute boiled down to the following alternative:

free credit or freedom of credit?

In June 1848, Proudhon was elected to the National Assembly, alongside Bastiat.

They were acquaintances and held each other in high regard. However, in 1849,

in a resounding controversy, Bastiat exchanged fourteen letters with him in the

columns of La Voix du Peuple. In this vigorous exchange, he clarified his stance

on monetary and banking issues. The dispute boiled down to the following alternative:

free credit or freedom of credit?

Proudhon saw the interest on capital as the initial cause of pauperism and inequality of conditions. He advocated for unlimited monetary creation by a state bank (the Exchange Bank or People's Bank), and saw in the "free credit" the solution to the social problem. On the other hand, Bastiat was a proponent of the freedom of banks, meaning the regulation of monetary circulation through the freedom of access to the profession, coupled with a necessary responsibility over one's own funds, and the freedom of competition.

Bastiat refuted his opponent in several stages. First, he analyzed the perverse effects of free credit and monetary creation. Such a system could only encourage the riskiest and most reckless actions by banks and private actors because they know they are covered by the state, that is, by taxpayer money: "It is a serious matter to place all men in a situation where they say: Let's try our luck with someone else's property; if I succeed, so much the better for me; if I fail, too bad for others." A prescient statement as it could apply to our era.

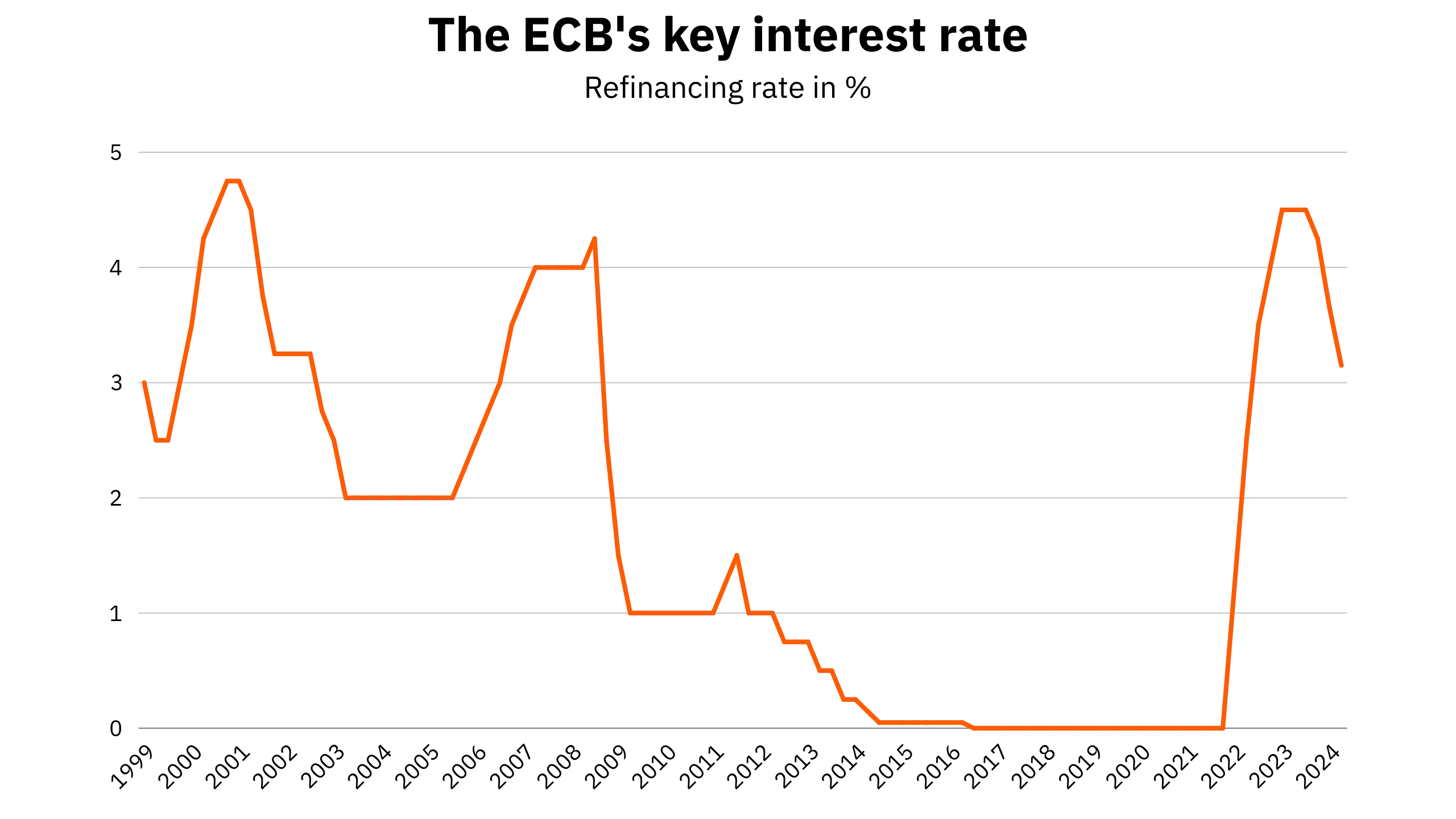

The policy of low interest rates practiced by central banks is a way to artificially create money. And the successive crises of the financial system over the last century, with the indebtedness of states, are its direct consequences.

Then Bastiat shows that it is possible to improve the purchasing power of the working classes, but by other means, more just and more effective. For him, the reduction of interest rates is also the goal of a liberal policy. But it is through the liberation and accumulation of capital that this is achieved, not by the abolition of interest, that is, free credit.

Indeed, according to Bastiat, the progress of humanity coincides with the formation of capital. In his pamphlet titled Capital and Rent, Bastiat makes us understand this with Robinson Crusoe on his island.

Without accumulated capital or materials, Robinson would be doomed to death.

He then explains that capital enriches the worker in two ways:

Without accumulated capital or materials, Robinson would be doomed to death.

He then explains that capital enriches the worker in two ways:

- It increases production, thus decreasing the price of goods for consumption;

- which has the effect of increasing wages.

In modern society, capital acts as an equalizing force. Indeed, Bastiat says:

When capital increases, it competes with itself; its remuneration decreases, or, in other words, the interest rate falls.

In conclusion, both Proudhon and Bastiat recognized the importance of capital accumulation and the tendency of some men to exploit others. However, they did not draw the same conclusions. Proudhon, like Marx, anticipated an increasing impoverishment of the masses in capitalist countries. Bastiat believed that capitalism would lead to unprecedented prosperity across all classes, and the development of an increasingly significant middle class. This is indeed what happened.

Economic Sophisms

What is Seen and What is Not Seen

In this chapter, I will unveil a brand-new technology, a revolutionary technology. A researcher has developed a pair of bionic glasses with an ultra-powerful mini-camera embedded in the front. This technology allows seeing details impossible to see with the naked eye. In the arms, there is an electronic chip that transmits images directly to the cloud via my smartphone.

The inventor of the first prototype of these glasses was Frédéric Bastiat in 1850 in a famous pamphlet: Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas. These glasses are those of the economist. They allow measuring the consequences of decisions made by the authorities on our lives. They are the glasses that "allow us to see what we do not see": the destruction caused by clientelist policies and false economic theories. Often we do not see their victims, nor their beneficiaries, in short, their real effects as opposed to the claims made in official speeches, what Bastiat calls "Economic Sophisms." The good economist, according to Bastiat, must describe the effects of political decisions on society. However, they must be attentive, not to their short-term effects on a particular group, but rather to their long-term consequences for society as a whole. Who are the victims and who are the beneficiaries of these policies? What are the hidden costs of a certain law or political decision? What would taxpayers have done instead of the government with the money that was taken from them in taxes? These are the questions posed by the good economist according to Bastiat.

Thus, in Public Works, Bastiat writes:

The State opens a road, builds a palace, straightens a street, digs a canal; by this, it gives work to certain workers, that's what is seen; but it deprives work from certain others, that's what is not seen.

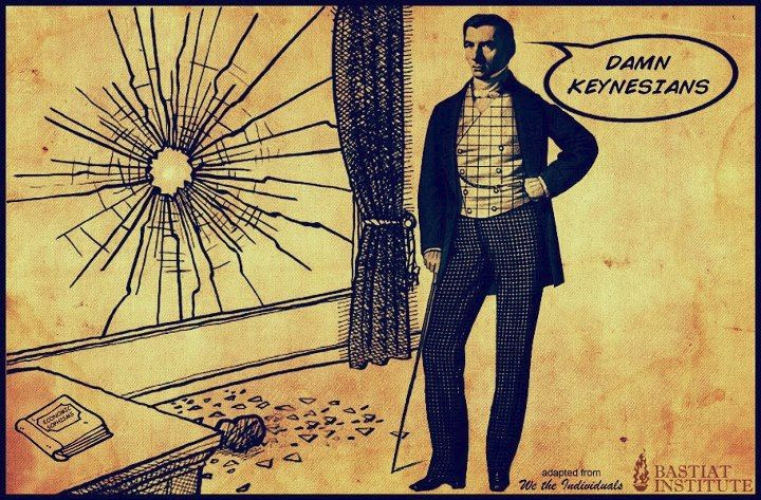

One of the most well-known sophisms is the broken window fallacy. Some claim that the breaking of a window in a house does not harm the economy since it benefits the glazier. But Bastiat will show that destruction is not in our interest because it does not create wealth. It costs more than it yields. The young boy who breaks a neighbor's window gives work to the glazier. But here is how his friends console him:

Every cloud has a silver lining. Such accidents keep the industry going. Everyone needs to live. What would become of glaziers if windows were never broken?

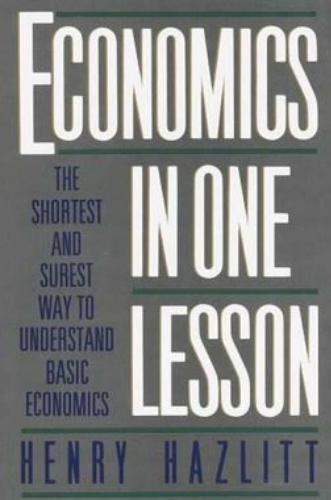

Thus, according to Keynes, the destruction of property, by forcing expenditure, would stimulate the economy and have a "multiplier effect" invigorating on production and employment. This is only what is seen.

But what is not seen is what the owner would have bought with that money, but which he now has to do without, with what he has to spend to repair his window. What is not seen is the lost opportunity of the owner of the broken window. He could have allocated the sum given to the glazier to something else. If he had not had to spend to repair the window, he could have spent the money for his own consumption, thus employing people for production.

Thus, there will be no more "stimulation" of the economy with the breaking of the window than without. However, there will have been a net loss in the first case: the value of the window.

The first lesson to learn is that a "good" decision or a "good" policy is one

that costs society less than what another allocation of resources could have

cost. The effectiveness of a policy should be judged not only based on its effects

but also on the basis of the alternatives that could have occurred. This is the

concept of "opportunity cost," dear to Bastiat.

The first lesson to learn is that a "good" decision or a "good" policy is one

that costs society less than what another allocation of resources could have

cost. The effectiveness of a policy should be judged not only based on its effects

but also on the basis of the alternatives that could have occurred. This is the

concept of "opportunity cost," dear to Bastiat.

The second lesson is that destruction does not stimulate the economy as Keynesians think but leads to impoverishment. The destruction of material goods does not have a positive effect on the economy, contrary to popular belief. To use the concluding words of Frédéric Bastiat's text: "society loses the value of the objects unnecessarily destroyed."

Let's take a current example. As soon as the automotive industry is struggling, policymakers imagine scrappage schemes to "relaunch" it. What we see is the increase in sales of Renault and Peugeot. What we do not see is the loss for other economic sectors and that cars in perfect working order are destroyed.

But there are other ways to boost the economy. If the State engages in major projects or invests funds in certain industrial sectors to support employment, isn't that good news for growth? Not any more, Bastiat would answer. Because by what would public spending be financed? By raising taxes or by debt, that is, by invisible but very real costs, which will impact growth. Moreover, the government produces nothing; it simply diverts resources from their private use. And what we do not see are the many things that could have been produced if the capital had not been withdrawn from the private sector to finance government programs.

Finally, nearly a century before Keynes, we can say that Bastiat refuted the Keynesian sophisms that claim that state indebtedness encourages the economy and that public spending produces growth.

The great lesson from this series of texts is that state intervention has perverse effects that are not seen. Only a good economist is capable of foreseeing them. Politics is what we see. The economy is what we do not see.

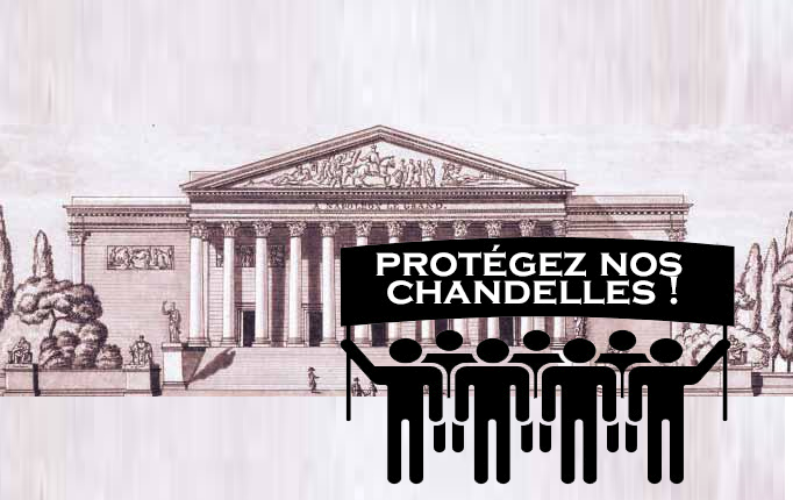

The Petition of the Candle Makers

In 1840, the Chamber of Deputies voted for a law increasing import taxes to protect the French industry. This is the famous economic patriotism, which we still encounter today.

above: Marine Le Pen, a French politician

above: Marine Le Pen, a French politician

Bastiat then composed a satirical text that later became one of his most famous works: "the petition of the candle makers". It illustrates how certain well-organized pressure groups of producers obtain undue privileges from the state, to the detriment of the citizens. At the same time, it demonstrates the absurd and destructive nature of protectionist legislation.

PROTECT OUR CANDLES!

In this petition, the candle makers ask the deputies for legal protection against a dangerous rival:

We suffer from the intolerable competition of a foreign rival who, it seems, is in such superior conditions for producing light that he floods our national market at a fabulously reduced price.

So, who is this unfair foreign competitor? It is none other than the sun. The producers then highlight the opportunity there would be in reserving "the national market for national labor", by ordering through a law to close "all windows, skylights, shades, shutters, blinds, curtains, fanlights, in a word all openings, holes, slits, and cracks through which the sunlight is accustomed to enter houses".

In other words, the candle makers attempt to demonstrate the harmful effects of a "foreign competitor" (the sun) on the economy of France. Because not only can the sun provide the same "product" as candles, but it does so for free. Two hundred years later, this story remains incredibly relevant. Consider the taxi drivers who ask for the law to ban VTCs and Uber. Think of the bookstores that want to ban Amazon.

Bastiat's real adversary in this fiction is political and electoral protectionism, one that relies solely on the greed of producers and the naivety of consumers. He unveils the collusion between the bad capitalist of the time and the State. Instead of innovating and adapting to the market, the bad capitalist is the one who seeks to gain a political advantage through protectionism. This always results in spoliation for the consumer, that is, an injustice. In short, protectionism is a deliberate policy in favor of producers against consumers. However, according to Bastiat, the true representatives of the general interest are the consumers, because we are all consumers.

Protectionism is also based on a hidden syllogism that turns out to be a fallacy:

- The more we work, the richer we are;

- The more difficulties we have to overcome, the more we work;

- Therefore, the more difficulties we have to overcome, the richer we are.

Let's illustrate this absurdity with a few short stories told by Bastiat. In Chapter III of the second series of Economic Sophisms, he imagines a carpenter who writes to the minister a petition asking for protectionist legislation. The carpenter thus formulates his request: Mr. Minister, make a law that stipulates that "No one will be able to use anything but beams and joists produced from blunt axes." In other words, make a law that prohibits the use of sharp axes in France. Thus, where one normally gives 100 axe blows, it will be necessary to give 300. Carpenters will be in high demand and therefore better paid.

In Chapter XVI, there is another very ironic text, titled: The Right Hand and the Left Hand. Following an investigation, a royal envoy drafts a report in which he proposes to the king to cut off, or at least tie up, all the right hands of the workers. Thus, he continues, work and consequently wealth will increase. Production will become much more difficult, which will necessitate the massive hiring of additional labor and an increase in wages. Pauperism will disappear from the country.

Following this logic of creating jobs at all costs, why not also replace trucks with wheelbarrows and shovels with teaspoons? All these sophisms have one thing in common: they confuse the means with the end. For Bastiat, the goal of the economy is not the preservation of jobs. We should not judge the utility of work by its duration and intensity but by its results: the satisfaction of needs, utility.

This confusion of means and end is found in the slogan "money is wealth." This is the axiom that governs the monetary policy of most states. Indeed, the artificial increase in the quantity of money allows banks to lend money to individuals and states to easily repay their debt, this is "what we see". But "what we do not see" is that this creation of money, not based on any real wealth creation, will lead to inflation and the ruin of savers.

True wealth, according to Bastiat, is therefore the set of useful things that we produce through work to satisfy our needs. Money is thus only a commonly used means of exchange, it only plays the role of an intermediary.

Plunder Through Taxation

When the rich lose weight, the poor die.

This quote, attributed to Lao-Tzu, describes the inevitable consequence of a taxation system that aims to hit the rich harder than others.

Yet, have you ever heard it said:

Taxation is the best investment: it's a fertilizing dew! See how many families it supports, and follow, in thought, its ricochets on industry: it's infinite, it's life.

In France, where public spending is considered a benefit, taxes are higher than in other countries. But Bastiat warns us right away: "In every public expenditure, behind the apparent good there is a more difficult to discern evil."

What is it about?

The economy describes the good or bad effects of political decisions on our lives. However, according to Bastiat, the economist must be attentive, not only to their short-term effects on a particular group but rather to their long-term consequences for society as a whole.

What we see is the labor and profit allowed by social contribution. What we do not see are the works that would be generated by this same contribution if it were left to the taxpayers. What we see is the labor and profit allowed by social contribution. What we do not see are the works that would be generated by this same contribution if it were left to the taxpayers.

F.Bastiat

From the outset, he refutes the still prevalent argument that public spending

funded by taxes creates jobs. Indeed, taxes create nothing since what is spent

by the state is no longer spent by taxpayers.

From the outset, he refutes the still prevalent argument that public spending

funded by taxes creates jobs. Indeed, taxes create nothing since what is spent

by the state is no longer spent by taxpayers.

Moreover, the state is more wasteful than individuals. Indeed, he reminds us, the state owns nothing; it produces no wealth. Public spending is often a source of waste because the immense sums confiscated from individuals escape the responsibility of their owners and are spent in their stead by bureaucrats, subject to pressure groups.

Of course, as payment for an equivalent public service received in exchange, taxation is entirely defensible. But in France, the state has assigned several roles to taxes.

Initially, it was supposed to cover common expenses. Then, taxes were also given a role in regulating the economy. In this case, politicians and bureaucrats have power that is only limited by their goodwill. Engrossed in their artificial constructs, they shape the economy by taxing and regulating sectors more or less according to their whims to favor or disfavor them.

Finally, a social role was assigned to taxes. They were made an instrument of social justice. Thus, taxes should not hit everyone in the same way. Taxes must be redistributive, from those "who have more" to those "who have less."

The problem is that taxes, as conceived, are subject to the arbitrariness of those in power. They favor or disfavor certain social categories depending on whether the power expects votes from them or not. Moreover, progressive rates yield little to the public treasury. However, they allow the majority to expropriate a minority and naturally become confiscatory.

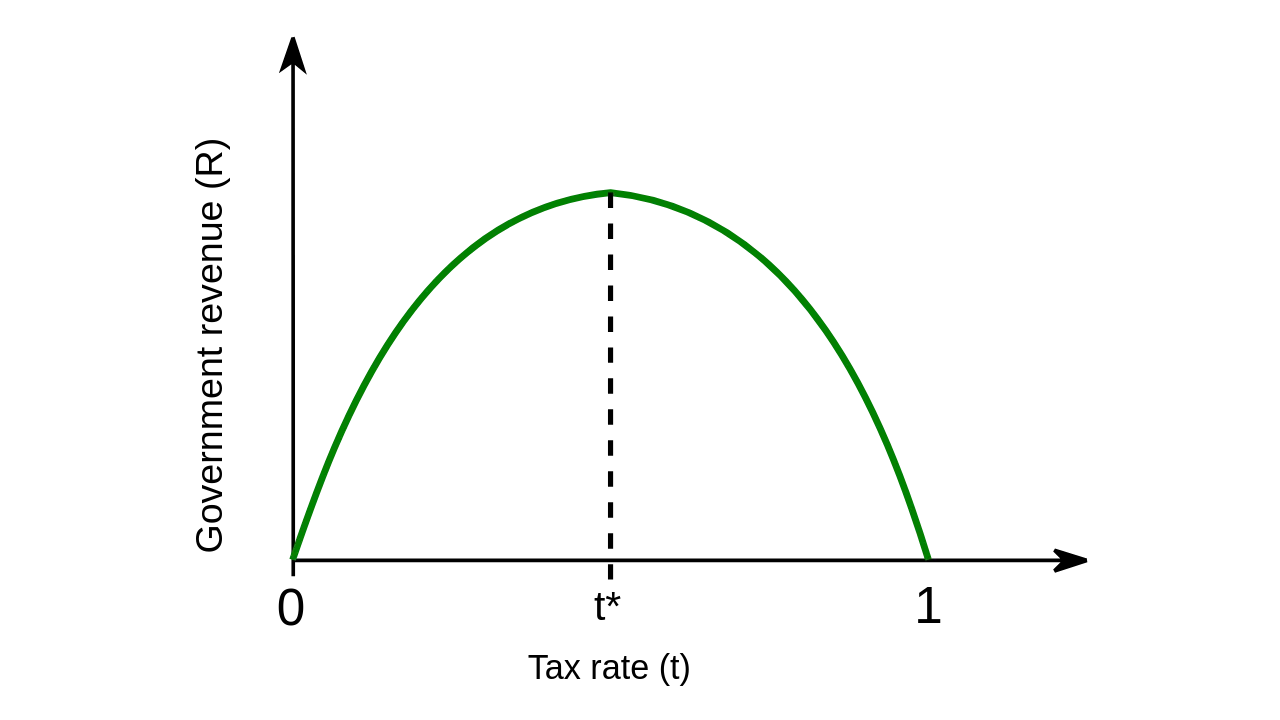

That's why Bastiat had already understood the Laffer curve. Arthur Laffer is an American economist known for his famous "curve" (an ellipse), published in 1974, which shows that the yield from taxes increases with the lowering of the tax rate. This is the theory of the diminishing return of excessive taxation.

Too much tax kills the tax.

Arthur Laffer

Politicians naively assume there is an automatic and fixed relationship between tax rates and tax revenues. They think they can double tax revenues by doubling the tax rate. According to Laffer, such an approach overlooks the fact that taxpayers may change their behavior in response to new incentives.

The Laffer curve shows that the government collects no revenue when tax rates are at 100%. Conversely, any reduction in taxes serves to stimulate economic activity and thus state revenues. Indeed, reducing marginal tax rates stimulates investment, work, creativity, and thus promotes economic growth. A sufficient reduction could produce enough economic stimulus to increase public revenues by significantly broadening the tax base.

Bastiat might add that as much importance should be placed on reducing state expenditures as on reducing taxes. Nonetheless, as Margaret Thatcher, a disciple of Frédéric Bastiat, so aptly put it:

The goal is not to make the rich poor, but to make the poor rich.

And she said this while addressing socialists.

The Two Moralities

Many people know "Tartuffe or the Impostor", the comedy by Molière in which a cunning devotee attempts to seduce Elmire and swindle her husband Orgon. How can one protect oneself against the deceptions of such a hypocrite who pretends to do you good while plotting against you?

Bastiat notes that there are two ways to put an end to this kind of imposture: correct Tartuffe or enlighten Orgon. Of course, there will always be Tartuffes, but their power to harm would be much reduced if there were fewer Orgons to listen to them.

The weakness of human reason is at the root of the misuse of freedom. It is the main limitation of humans and the cause of many evils. Therefore, it is necessary to enlighten consciences about the useful or harmful, and thus just or unjust, nature of human acts, whether individual or collective.

However, there are two complementary ways to enlighten the judgment of citizens, as Bastiat outlines in a chapter of the second series of Economic Sophisms titled "The Two Moralities".

- First, there is a "philosophical or religious morality" that acts by purifying and correcting human action (the man as an agent);

- then, there is an "economic morality", which acts by showing man "the necessary consequences of his acts" (the man as a patient).

In fact, these are two perfectly complementary moral frameworks.

- The first addresses the heart and encourages individuals to do good; it is the religious or philosophical morality. It is the most noble. It roots in the heart of man the consciousness of his duty. It tells him:

Improve yourself; purify yourself; stop doing evil; do good, tame your passions; sacrifice your interests; do not oppress your neighbor whom it is your duty to love and relieve; be just first and charitable afterwards.

In short, it teaches virtue, the selfless act. This morality, Bastiat says, will eternally be the most beautiful and touching, for it shows what is best in man.

- The other helps to denounce and combat evil through the knowledge of its effects, it is the economic morality. It addresses the intellect and not the heart, aiming to enlighten the victim about the negative effects of a behavior. It reinforces the lessons of experience. It strives to spread common sense, knowledge, and mistrust to the oppressed masses, making oppression more difficult.

This economic morality aspires to the same result as the religious morality, but starting from the effects of human actions. It teaches us to react against unjust or harmful actions and to defend those that are just or useful.

Bastiat here highlights the role of science, and in particular of economic science. Although different from that of traditional morality, its role is nonetheless necessary to combat spoliation in all its forms. Morality attacks vice in its intention, it educates the will. On the other hand, science attacks vice by understanding its effects, thus facilitating the triumph of virtue.

Concretely, economic science, described by Bastiat as defensive morality, consists of refuting economic sophisms in order to completely discredit them, and thus strip the plundering class of its justification and power.

Political Economy, therefore, has an obvious practical utility. It reveals spoliation in hidden costs, obstacles to competition, and all forms of protectionism.

Once again, there would be fewer Tartuffes if there were fewer Orgons to listen to them. Here is what Bastiat has to say on this matter:

Let religious morality therefore touch the hearts of Tartuffes if it can. The task of political economy is to enlighten their dupes. Of these two approaches, which one works most effectively for social progress? Must it be said? I believe it is the second. I fear that humanity cannot escape the necessity of first learning defensive morality.

Of course, political economy is not the universal science; it does not exclude philosophical and religious approaches. "But who has ever displayed such an exorbitant claim in its name?" Bastiat wonders.

One thing is certain, it is not the politics which can change the course of things and perfect man. On the contrary, it is necessary to limit the politics and confine to its strict role, which is safety. It is rather in the cultural, familial, religious, and associative fields, through work on ideas, through education and instruction, in short, through civil society, that responsibility and solidarity can be strengthened.

Economic Harmonies

The Miracle of the Market

Can a harmonious society do without written laws, rules, repressive measures? If men are left free, won't we witness disorder, anarchy, disorganization? How to avoid creating a mere juxtaposition of individuals acting outside of any concert, if not through laws and a centralized political organization?

This is the argument often invoked by those who demand market regulation or society alone capable of coordinating individuals into a coherent and harmonious whole.

This is not Bastiat's view. According to him, the social mechanism, like the celestial mechanism or the mechanism of the human body, obeys general laws. In other words, it is already a harmoniously organized whole. And the engine of this organization is the free market.

The miracle of the free market, he tells us, is that it uses knowledge that no one person can possess alone and that it provides satisfactions far superior to anything an artificial organization could do.

Bastiat gives a few examples to illustrate the benefits of this market. We have become so accustomed to this phenomenon that we no longer pay attention to it. Let's consider a carpenter in a village, he says, and observe all the services he provides to society and all those he receives:

Every day, upon waking up, he dresses, and he personally made none of his clothes. Yet, for these clothes to be available to him, an enormous amount of work, industry, transportation, and ingenious inventions had to be accomplished worldwide.

Then he has breakfast. For the bread he eats to arrive on his table every morning, lands had to be cleared, plowed; iron, steel, wood, stone had to be converted into work tools; all things that each, taken separately, assume an incalculable mass of work put into play, not only in space but in time.

This man will send his son to school, to receive an education that presupposes research, many years of prior study.

He goes outside: he finds a paved and lit street.His property is contested: he will find lawyers to defend his rights, judges to maintain them, justice officers to execute the sentence; all things that still presuppose acquired knowledge, hence enlightenment and means of existence.

Bastiat describes the market as a decentralized and invisible tool of cooperation. Through the price system, it transmits information about everyone's needs and skills, it connects people who want to cooperate to improve their existence.

What is striking, Bastiat concludes, is the immense disproportion that exists between the benefits this man draws from society and those he would provide to himself if he were reduced to his own resources. In a single day, he consumes goods that he could not produce himself.

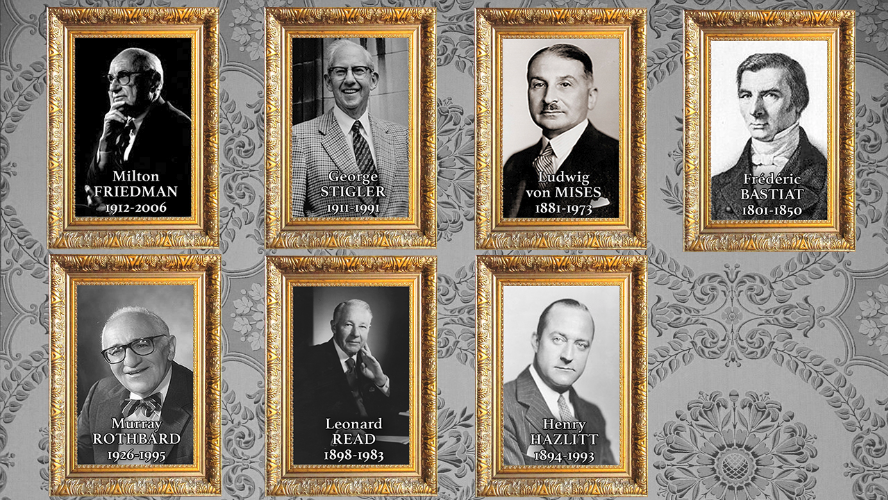

In 1958, American writer Leonard Read (Foundation for Economic Education) published a short essay in The Freeman magazine, written in the manner of Bastiat, which became very famous: "I, Pencil". This text is a metaphor for what a free market is. It begins like this:

I am a lead pencil, an ordinary wooden pencil familiar to all boys and girls and adults who can read and write. It is one of the simplest objects in human civilization. And yet not a single person on this earth knows how to produce me.

It revisits Bastiat's idea of an invisible cooperation among millions of individuals

who do not know each other, leading to the construction of something as mundane

as a pencil. No one knows how to make a pencil on their own. Yet, millions of

human beings unknowingly participate in the creation of this simple pencil, exchanging

and coordinating their knowledge and skills within a price system without any

superior authority dictating their conduct. This story demonstrates that free

individuals working in pursuit of their legitimate interest act more for the

benefit of society than any planned and centralized economic strategy.

It revisits Bastiat's idea of an invisible cooperation among millions of individuals

who do not know each other, leading to the construction of something as mundane

as a pencil. No one knows how to make a pencil on their own. Yet, millions of

human beings unknowingly participate in the creation of this simple pencil, exchanging