name: Introduction to formal Cryptography goal: A deep-dive introduction to the science and practice of cryptography. objectives:

- Explore Beale ciphers and modern cryptographic methods to understand basic and historical concepts of cryptography.

- Delve into number theory, groups, and fields to master key mathematical concepts underlying cryptography.

- Study the RC4 stream cipher and AES with a 128-bit key to learn about symmetric cryptographic algorithms.

- Investigate the RSA cryptosystem, key distribution, and hash functions to explore asymmetric cryptography.

Deep-dive into cryptographie

It is difficult to find many materials that offer a good middle ground in cryptography education.

On the one hand, there are lengthy, formal treatises, really only accessible to those with a strong background in mathematics, logic, or some other formal discipline. On the other hand, there are very high-level introductions that really hide too many of the details for anyone that is at least a bit curious.

This introduction to cryptography seeks to capture the middle ground. While it should be relatively challenging and detailed for anyone new to cryptography, it is not the rabbit hole of a typical foundational treatise.

Introduction

Course overview

bb8a8b73-7fb2-50da-bf4e-98996d79887b Welcome to the CYP302 course!

This book offers a deep-dive introduction to the science and practice of cryptography. Where possible it focuses on conceptual, rather than formal exposition of the material.

This educational content is adapted from the book and repo JWBurgers. While the author has graciously permitted its educational use, all intellectual property rights remain with the original creator.

Motivation and aims

It is difficult to find many materials that offer a good middle ground in cryptography education.

On the one hand, there are lengthy, formal treatises, really only accessible to those with a strong background in mathematics, logic, or some other formal discipline. On the other hand, there are very high-level introductions that really hide too many of the details for anyone that is at least a bit curious.

This introduction to cryptography seeks to capture the middle ground. While it should be relatively challenging and detailed for anyone new to cryptography, it is not the rabbit hole of a typical foundational treatise.

Target audience

From developers to the intellectually curious, this book is useful for anyone that wants more than a superficial understanding of cryptography. If your aim is to master the field of cryptography, then this book is also a good starting point.

Reading guidelines

The book currently contains seven chapters: "What is Cryptography?" (Chapter 1), "Mathematical Foundations of Cryptography I" (Chapter 2), "Mathematical Foundations of Cryptography II" (Chapter 3), "Symmetric Cryptography" (Chapter 4), "RC4 and AES" (Chapter 5), "Asymmetric Cryptography" (Chapter 6), and "The RSA cryptosystem" (Chapter 7). A final chapter, "Cryptography in Practice," will still be added. It focuses on various cryptographic applications, including transport layer security, onion routing, and Bitcoin's value exchange system.

Unless you have a strong background in mathematics, number theory is probably the most difficult topic in this book. I offer an overview of it in Chapter 3, and it also appears in the exposition of AES in Chapter 5 and the RSA cryptosystem in Chapter 7.

If you are really struggling with the formal details in these parts of the book, I recommend you settle for a high-level reading of them the first time around.

Acknowledgements

The most influential book in shaping this one has been Jonathan Katz and Yehuda Lindell’s Introduction to Modern Cryptography, CRC Press (Boca Raton, FL), 2015. An accompanying course is available on Coursera called "Cryptography."

The main additional sources that have been helpful in creating the overview in this book are Simon Singh, The Code Book, Fourth Estate (London, 1999); Christof Paar and Jan Pelzl, Understanding Cryptography, Springer (Heidelberg, 2010) and a course based on the book by Paar called “Introduction to Cryptography”; and Bruce Schneier, Applied Cryptography, 2nd edn, 2015 (Indianapolis, IN: John Wiley & Sons).

I will only cite very specific information and results I take from these sources, but want to acknowledge my general indebtedness to them here.

For those readers who wish to seek out more advanced knowledge on cryptography after this introduction, I highly recommend Katz and Lindell’s book. Katz's course on Coursera is somewhat more accessible than the book.

Contributions

Please have a look at the contributions file in the repository for some guidelines on how to support the project.

Notation

Key terms:

Key terms in the primers are introduced by making them bold. For instance, the introduction of the Rijndael cipher as a key term would look as follows: Rijndael cipher.

Key terms are explicitly defined, unless they are proper names or their meaning is obvious from the discussion.

Any definition is usually given upon introduction of a key term, though sometimes it is more convenient to leave the definition until a later point.

Emphasized words and phrases:

Words and phrases are emphasized via italics. For instance, the phrase "Remember your password" would look as follows: Remember your password.

Formal notation:

The formal notation mainly concerns variables, random variables, and sets.

- Variables: These are usually just indicated by a lowercase letter (e.g., "x" or "y"). Sometimes they are capitalized for clarity (e.g., "M" or "K").

- Random variables: These are always indicated by an uppercase letter (e.g., "X" or "Y")

- Sets: These are always indicated by bold, upper-case letters (e.g., S)

Ready to explore the fascinating world of cryptography? Let's go!

What is Cryptography?

The Beale ciphers

Let’s start our enquiry into the field of cryptography with one of the more charming and entertaining episodes in its history: that of the Beale ciphers. [1]

The story of the Beale ciphers is, in my opinion, more likely to be fiction than reality. But it supposedly transpired as follows.

In both the Winter of 1820 and 1822, a man named Thomas J. Beale stayed at an inn owned by Robert Morriss in Lynchburg (Virginia). At the end of Beale’s second stay, he handed Morriss an iron box with valuable papers for safekeeping.

A few months later, Morriss received a letter from Beale dated May 9, 1822. It emphasized the great value of the contents of the iron box and related some instructions to Morriss: if neither Beale nor any of his associates ever came to claim the box, he should open it precisely ten years from the date of the letter (that is, May 9, 1832). Some of the papers inside would be written in regular text. Several others, however, would be “unintelligible without the aid of a key.” This “key” would, then, be delivered to Morriss by an unnamed friend of Beale’s in June of 1832.

Despite the clear instructions, Morriss did not open the box in May of 1832 and Beale’s mysterious friend never turned up in June of that year. It was not until 1845 that the innkeeper finally decided to open the box. In it, Morriss found a note explaining how Beale and his associates discovered gold and silver out West and buried it, together with some jewelry, for safekeeping. In addition, the box contained three ciphertexts: that is, texts written in code which require a cryptographic key, or a secret, and an accompanying algorithm to unlock. This process of unlocking a ciphertext is known as decryption, while the locking process is known as encryption. (As explained in Chapter 3, the term cipher can take on various meanings. In the name "Beale ciphers", it is short for ciphertexts.)

The three ciphertexts that Morriss found in the iron box each consist of a series of numbers separated by commas. According to Beale’s note, these ciphertexts separately provide the location of the treasure, the contents of the treasure, and a list of names with rightful heirs to the treasure and their shares (the latter information being relevant in case Beale and his associates never came to claim the box).

Morris attempted to decrypt the three ciphertexts for twenty years. This would have been easy with the key. But Morriss did not have the key and was unsuccessful in his attempts to recover the original texts, or plaintexts as they are typically called in cryptography.

Nearing the end of his life, Morriss passed the box on to a friend in 1862. This friend subsequently published a pamphlet in 1885, under the pseudonym J.B. Ward. It included a description of the (alleged) history of the box, the three ciphertexts, and a solution that he had found for the second ciphertext. (Apparently, there is one key for each ciphertext, and not one key that works on all three ciphertexts as Beale originally seems to have suggested in his letter to Morriss.)

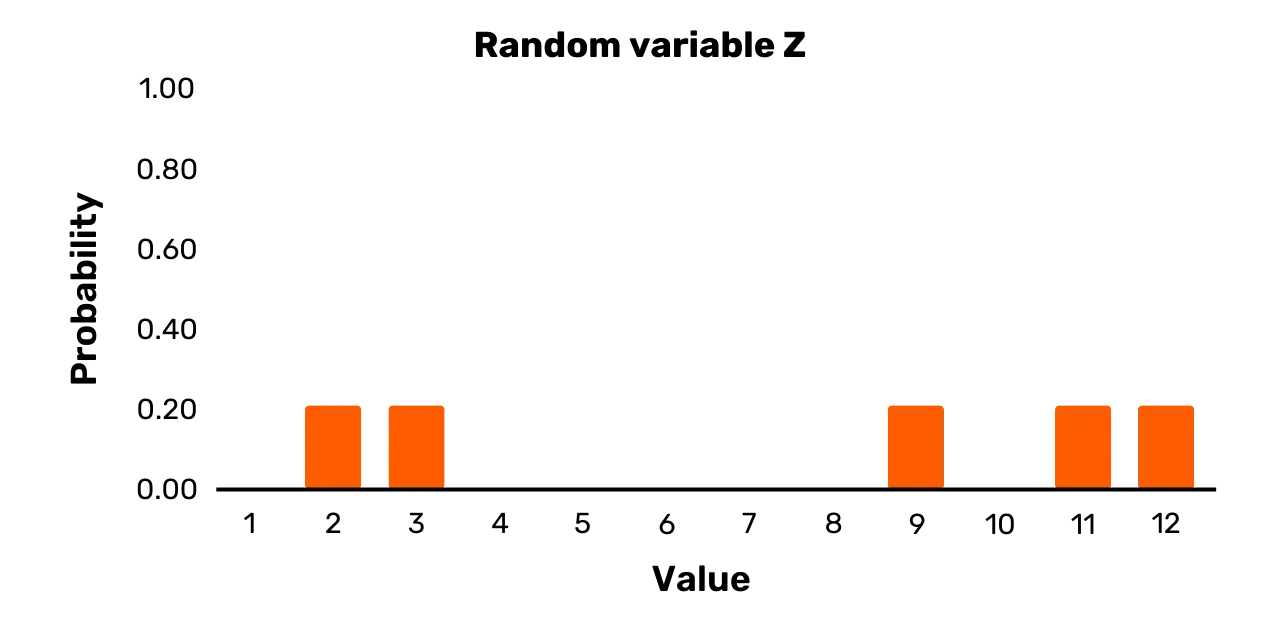

You can see the second ciphertext in Figure 2 below. [2] The key to this ciphertext is the United States Declaration of Independence. The decryption procedure comes down to the applying the following two rules:

- For any number n in the ciphertext, locate the nth word in the United States Declaration of Independence

- Replace the number n with the first letter of the word you found

Figure 1: Beale cipher no. 2

For instance, the first number of the second ciphertext is 115. The 115th word of the Declaration of Independence is “instituted,” so the first letter of the plaintext is “i.” The ciphertext does not directly indicate word spacing and capitalization. But after decrypting the first few words, you can logically deduce that the first word of the plaintext was simply “I.” (The plaintext starts with the phrase “I have deposited in the county of Bedford.”)

After decryption, the second message provides the detailed contents of the treasure (gold, silver, and jewels), and suggests that it was buried in iron pots and covered with rocks in Bedford County (Virginia). People love a good mystery, so great efforts have been expended on decrypting the other two Beale ciphers, particularly the one describing the location of the treasure. Even various prominent cryptographers have tried their hands on them. However, as of yet, no one has been able to decrypt the other two ciphertexts.

Notes:

[1] For a good summary of the story, see Simon Singh, The Code Book, Fourth Estate (London, 1999), pp. 82-99. A short movie of the story was made by Andrew Allen in 2010. You can find the movie, “The Thomas Beale Cipher,” on its website.

[2] This image is available on the Wikipedia page for the Beale ciphers.

Modern cryptography

Colorful stories such as that of the Beale ciphers are what most of us associate with cryptography. Yet, modern cryptography differs in at least four important ways from these types of historical examples.

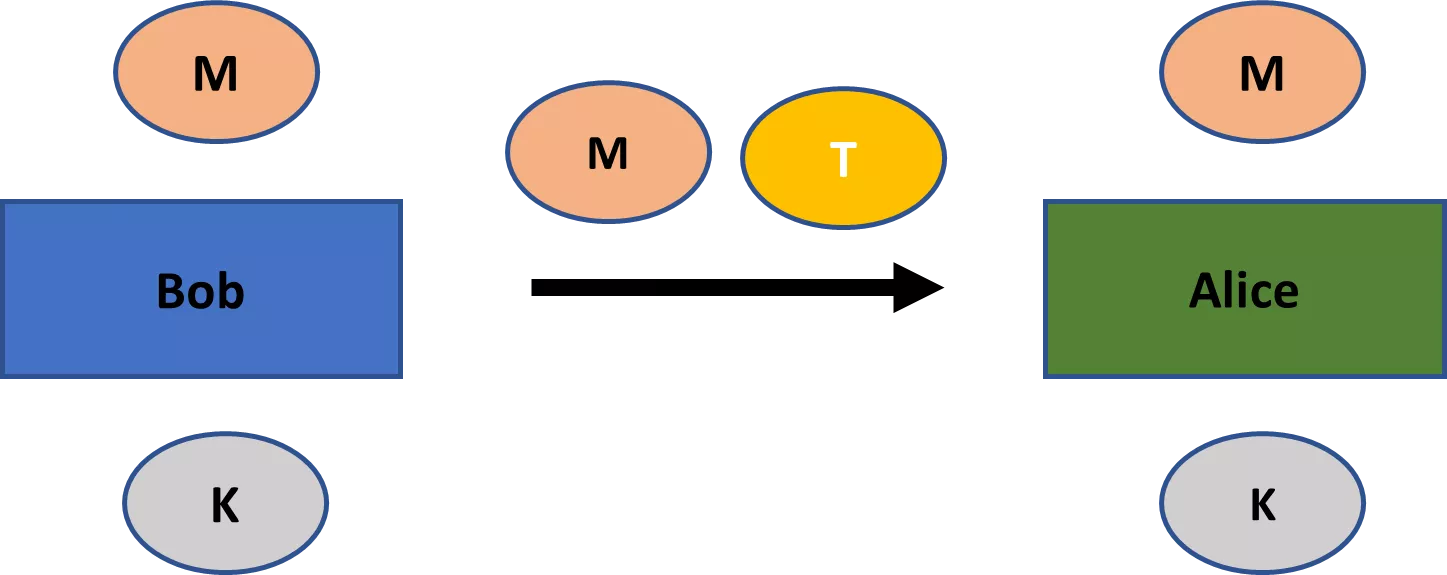

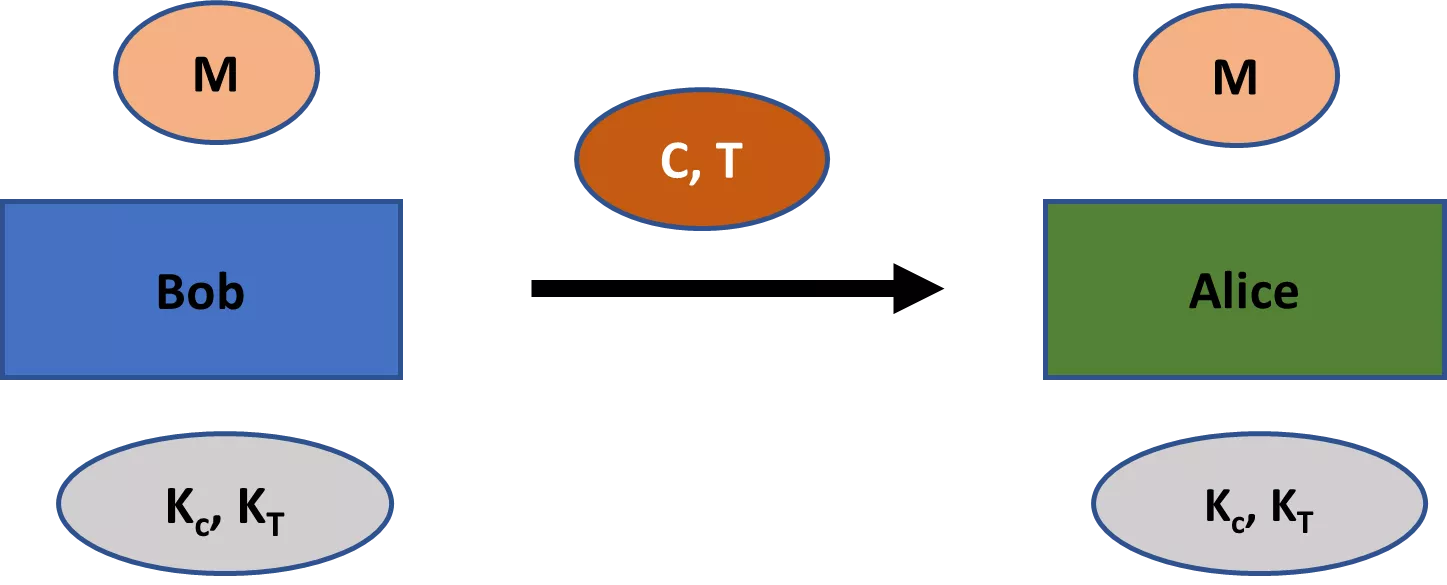

First, historically cryptography has only been concerned with secrecy (or confidentiality). [3] Ciphertexts would be created to ensure that only certain parties could be privy to the information in the plaintexts, as in the case of the Beale ciphers. In order for an encryption scheme to serve this purpose well, decrypting the ciphertext should only be feasible if you have the key.

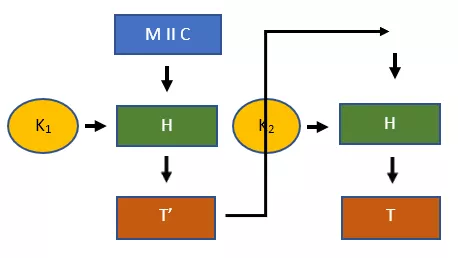

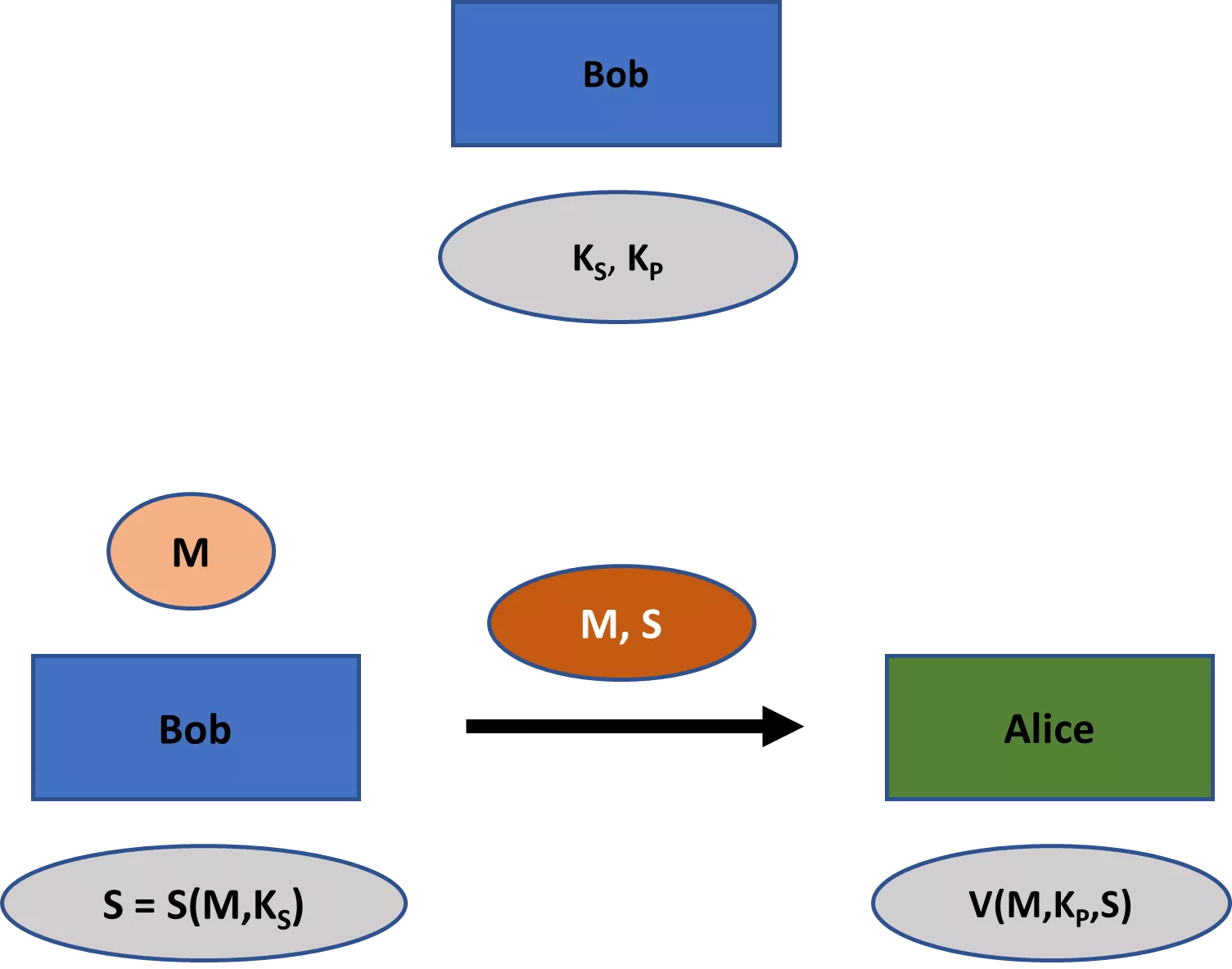

Modern cryptography is concerned with a wider range of themes than just secrecy. These themes include primarily (1) message integrity—that is, assuring that a message has not been changed; (2) message authenticity—that is, assuring that a message has really come from a particular sender; and (3) non-repudiation—that is, assuring that a sender cannot falsely deny later that she sent a message. [4]

An important distinction to keep in mind is, thus, between an encryption scheme and a cryptographic scheme. An encryption scheme is just concerned with secrecy. While an encryption scheme is a cryptographic scheme, the reverse is not true. A cryptographic scheme can also serve the other main themes of cryptography, including integrity, authenticity, and non-repudiation.

The themes of integrity and authenticity are just as important as secrecy. Our modern communications systems would not be able to function without guarantees regarding the integrity and authenticity of communications. Non-repudiation is also an important concern, such as for digital contracts, but less ubiquitously needed in cryptographic applications than secrecy, integrity, and authenticity.

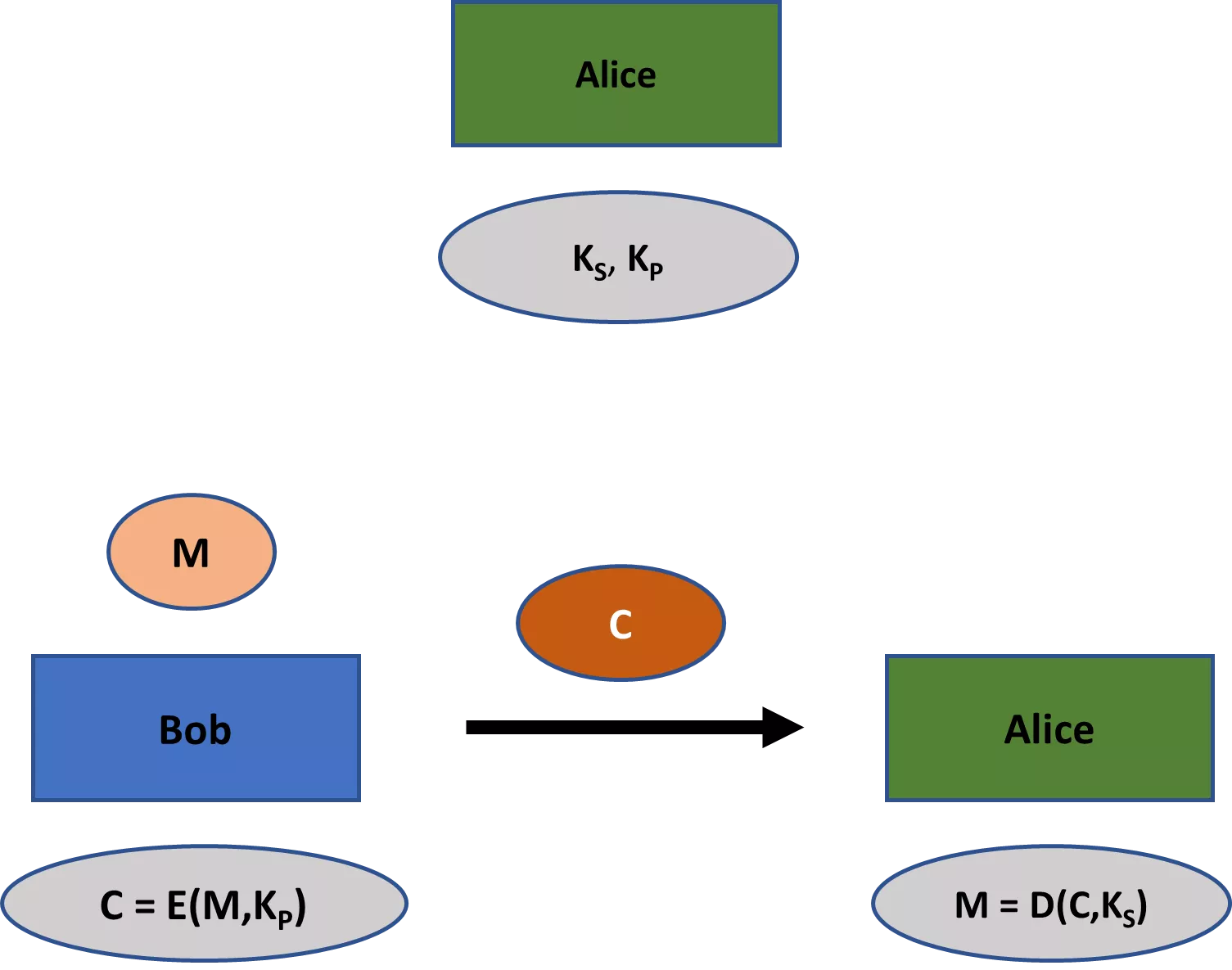

Second, classical encryption schemes such as the Beale ciphers always involve one key that was shared among all the relevant parties. However, many modern cryptographic schemes involve not just one, but two keys: a private and a public key. While the former should remain private in any applications, the latter is typically public knowledge (hence, their respective names). Within the realm of encryption, the public key can be used to encrypt the message, while the private key can be used for decryption.

The branch of cryptography that deals with schemes where all parties share one key is known as symmetric cryptography. The single key in such a scheme is usually called the private key (or secret key). The branch of cryptography which deals with schemes that require a private-public key pair is known as asymmetric cryptography. These branches are sometimes also referred to as private key cryptography and public key cryptography, respectively (though this can raise confusion, as public key cryptographic schemes also have private keys).

The advent of asymmetric cryptography in the late 1970s has been one of the most important events in the history of cryptography. Without it, most of our modern communication systems, including Bitcoin, would not be possible, or at least very impractical.

Importantly, modern cryptography is not exclusively the study of symmetric and assymetric key cryptographic schemes (though that covers much of the field). For instance, cryptography is also concerned with hash functions and pseudorandom number generators, and you can build applications on these primitives that are not related to symmetric or assymetric key cryptography.

Third, classical encryption schemes, like those used in the Beale ciphers, were more art than science. Their perceived security was largely based on intuitions regarding their complexity. They would typically be patched when a new attack on them was learned, or dropped entirely if the attack was particularly severe. Modern cryptography, however, is a rigorous science with a formal, mathematical approach to both developing and analyzing cryptographic schemes. [5]

Specifically, modern cryptography centers on formal proofs of security. Any proof of security for a cryptographic scheme proceeds in three steps:

- The statement of a cryptographic definition of security, that is, a set of security goals and the threat posed by the attacker.

- The statement of any mathematical assumptions with regards to computational complexity of the scheme. For instance, a cryptographic scheme may contain a pseudorandom number generator. Though we cannot prove these exist, we can assume that they do.

- The exposition of a mathematic proof of security of the scheme on the basis of the formal notion of security and any mathematical assumptions.

Fourth, whereas historically cryptography was primarily utilized in military settings, it has come to permeate our daily activities in the digital age. Whether you are banking online, posting on social media, buying a product from Amazon with your credit card, or tipping a friend bitcoin, cryptography is the sine qua non of our digital age.

Given these four aspects to modern cryptography, we might characterize modern cryptography as the science concerned with the formal development and analysis of cryptographic schemes to secure digital information against adversarial attacks. [6] Security here should be broadly understood as preventing attacks that damage secrecy, integrity, authentication, and/or non-repudiation in communications.

Cryptography is best seen as a subdiscipline of cybersecurity, which is concerned with preventing the theft, damaging, and misuse of computer systems. Note that many cybersecurity concerns have little or only a partial connection to cryptography.

For instance, if a company houses expensive servers locally, they may be concerned with securing this hardware from theft and damage. While this is a cybersecurity concern, it has little to do with cryptography.

For another example, phishing attacks are a common problem in our modern age. These attacks attempt to deceive people via an e-mail or some other message medium to relinquish sensitive information such as passwords or credit card numbers. While cryptography can help address phishing attacks to a certain degree, a comprehensive approach requires more than just using some cryptography.

Notes:

[3] To be exact, the important applications of cryptographic schemes have been concerned with secrecy. Kids, for instance, frequently use simple cryptographic schemes for “fun”. Secrecy is not really a concern in those cases.

[4] Bruce Schneier, Applied Cryptography, 2nd edn, 2015 (Indianapolis, IN: John Wiley & Sons), p. 2.

[5] See Jonathan Katz and Yehuda Lindell, Introduction to Modern Cryptography, CRC Press (Boca Raton, FL: 2015), esp. pp. 16–23, for a good description.

[6] Cf. Katz and Lindell, ibid., p. 3. I think their characterization has some issues, so present a slightly different version of their statement here.

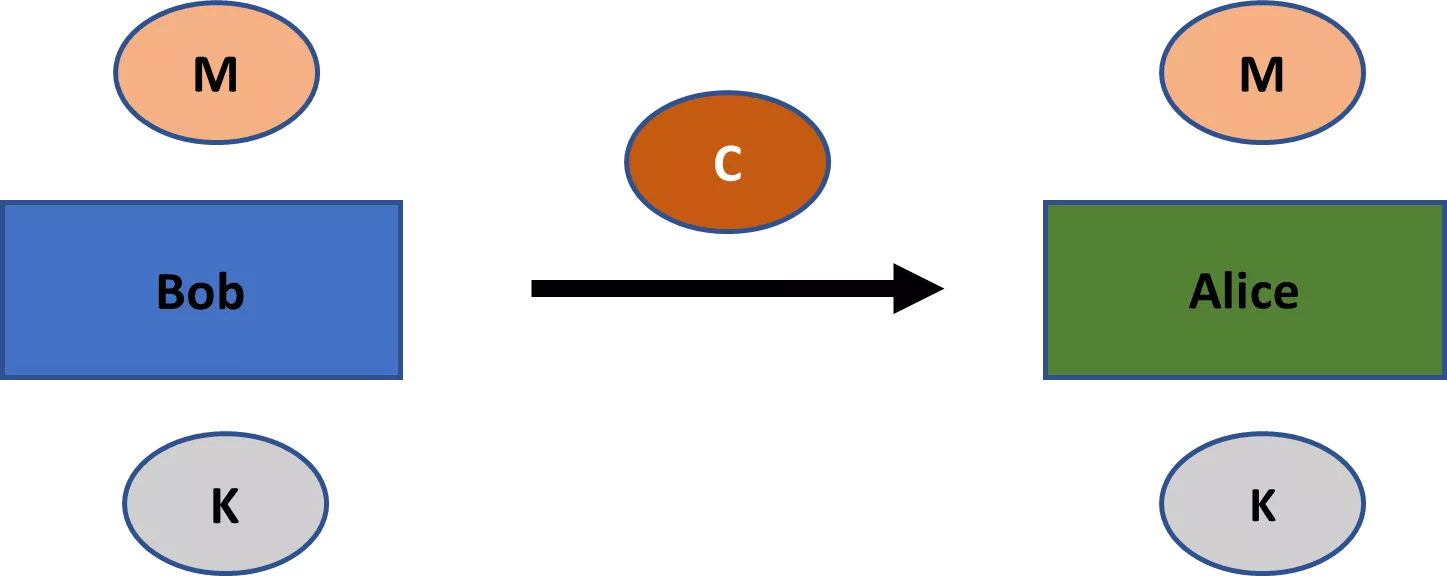

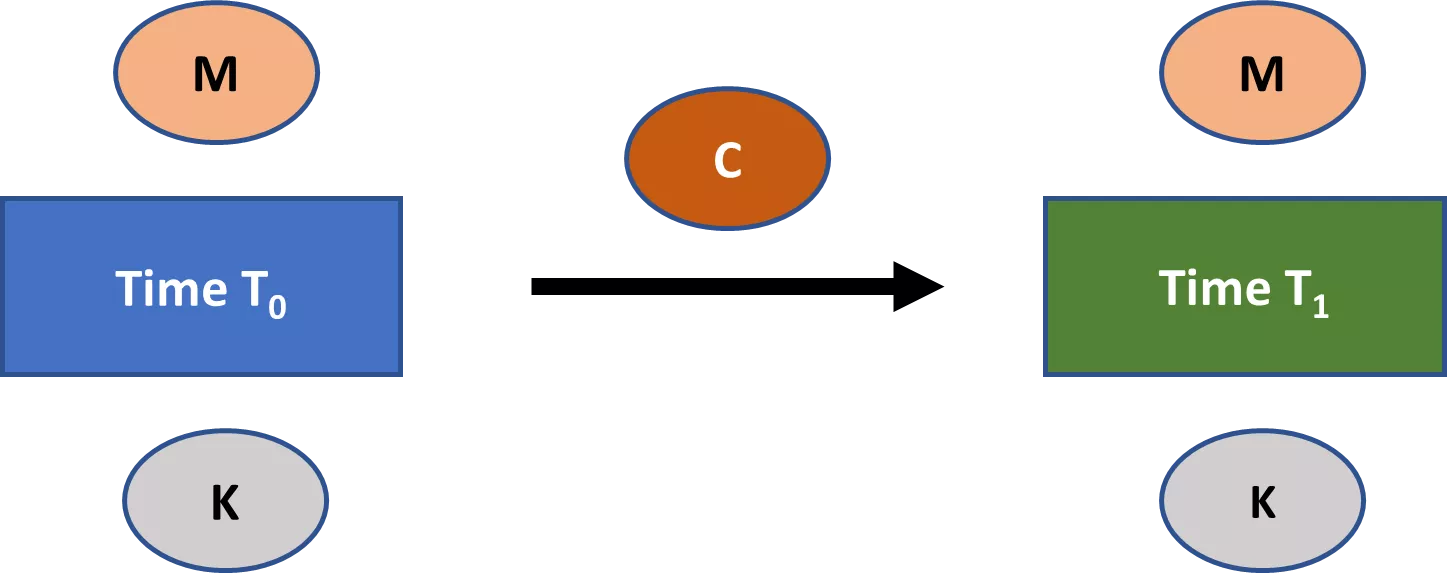

Open communications

Modern cryptography is designed to provide security assurances in an open communications environment. If our communication channel is so well-protected that eavesdroppers have no chance of manipulating or even just observing our messages, then cryptography is superfluous. Most of our communication channels, however, are hardly this well-guarded.

The backbone of communication in the modern world is a massive network of fiber optic cables. Making phone calls, viewing television, and browsing the web in a modern household generally relies on this network of fiber optic cables (a small percentage may rely purely on satelites). It is true that you might have different data connections in your home, such as coaxial cable, (asymmetric) digital subscriber line, and fiber optic cable. But, at least in the developed world, these different data mediums quickly join outside your house to a node in a massive network of fiber optic cables which connects the entire globe. Exceptions are some remote areas of the developed world, such as in the United States and Australia, where data traffic might still also travel substantial distances over traditional copper telephone wires.

It would be impossible to prevent potential attackers from physically accessing this network of cables and its supporting infrastructure. In fact, we already know that most of our data is intercepted by various national intelligence agencies at crucial intersections of the Internet.[7] This includes everything from Facebook messages to website addresses that you visit.

While surveilling data on a massive scale requires a powerful adversary, such as a national intelligence agency, attackers with only few resources can easily attempt to snoop at a more local scale. Though this can happen at the level of tapping wires, it is far easier just to intercept wireless communications.

Most of our local network data—whether in our homes, at the office, or in a café—now travels via radio waves to wireless access points on all-in-one routers, rather than through physical cables. So an attacker needs little resources to intercept any of your local traffic. This is particularly concerning as most people do very little to protect the data that travels across their local networks. In addition, potential attackers can also target our mobile broadband connections, such as 3G, 4G, and 5G. All these wireless communications are an easy target for attackers.

Hence, the idea of keeping communications secret by protecting the communication channel is a hopelessly delusional aspiration for much of the modern world. Everything we know warrants severe paranoia: you should always assume that someone is listening. And cryptography is the main tool we have to obtain any kind of security in this modern environment.

Notes:

[7] See, for instance, Olga Khazan, “The creepy, long-standing practice of undersea cable tapping”, The Atlantic, July 16, 2013 (available at The Atlantic).

Mathematical Foundations of Cryptography 1

Random variables

Cryptography relies on mathematics. And if you want to build more than a superficial understanding of cryptography, you need to be comfortable with that mathematics.

This chapter introduces most of the basic mathematics you will encounter in learning cryptography. The topics include random variables, modulo operations, XOR operations, and pseudorandomness. You should master the material in these sections for any non-superficial understanding of cryptography.

The next section deals with number theory, which is much more challenging.

Random variables

A random variable is typically denoted by a non-bold, uppercase letter. So,

for instance, we might talk about a random variable X, a random variable Y, or a

random variable Z. This is

the notation I will also employ from here on out.

A random variable can take on two or more possible values, each with a certain positive probability. The possible values are listed in the outcome set.

Each time you sample a random variable, you draw a particular value from its outcome set according to the defined probabilities.

Lets turn to a simple example. Suppose a variable X that is defined as follows:

- X has the outcome set

\{1,2\}

Pr[X = 1] = 0.5Pr[X = 2] = 0.5It is easy to see that X is a

random variable. First, there are two or more possible values that X can take on, namely 1 and 2. Second, each possible

value has a positive probability of occurring whenever you sample X, namely 0.5.

All that a random variable requires is an outcome set with two or more possibilities, where each possibility has a positive probability of occurring upon sampling. In principle, then, a random variable can be defined abstractly, devoid of any context. In this case, you might think of “sampling” as running some natural experiment to determine the value of the random variable.

The variable X above was

defined abstractly. You might, thus, think of sampling the variable X above as flipping a fair coin and assigning “2” in the case of heads and “1”

in the case of tails. For each sample of X, you flip the coin again.

Alternatively, you might also think of sampling X, as rolling a fair die and assigning “2” in case the die lands 1, 3, or 4, and assigning “1” in case

the die lands 2, 5, or 6. Each time you sample X, you roll the die again.

Really, any natural experiment that would allow you to define the

probabilities of the possible values of X above can be imagined with respect to the drawing.

Frequently, however, random variables are not just introduced abstractly. Instead, the set of possible outcome values has explicit real-world meaning (rather than just as numbers). In addition, these outcome values might be defined against some specific type of experiment (rather than as any natural experiment with those values).

Lets now consider an example of variable X that is not defined abstractly. X is defined as follows in order to determine

which of two teams starts a football game:

Xhas the outcome set {red kicks off,blue kicks off}- Flip a particular coin

C: tails = “red kicks off”; heads = “blue kicks off”

Pr [X = \text{red kicks off}] = 0.5Pr [X = \text{blue kicks off}] = 0.5In this case, the outcome set of X is provided with a concrete meaning,

namely which team starts in a football game. In addition, the possible

outcomes and their associated probabilities are determined by a concrete

experiment, namely flipping a particular coin C.

Within discussions of cryptography, random variables are usually introduced against an outcome set with real-world meaning. It might be the set of all messages that could be encrypted, known as the message space, or the set of all keys the parties using the encryption can choose from, known as the key space.

Random variables in discussions on cryptography are, however, not usually defined against some specific natural experiment, but against any experiment that might yield the right probability distributions.

Random variables can have discrete or continuous probability distributions.

Random variables with a discrete probability distribution—that is, discrete random variables—have a finite number of possible

outcomes. The random variable X in both examples given so far

was discrete.

Continuous random variables can instead take on values in one or more intervals. You might say, for instance, that a random variable, upon sampling, will take on any real value between 0 and 1, and that each real number in this interval is equally likely. Within this interval, there are infinitely possible values.

For cryptographic discussions, you will only need to understand discrete random variables. Any discussion of random variables from here on out should, therefore, be understood as referring to discrete random variables, unless specifically stated otherwise.

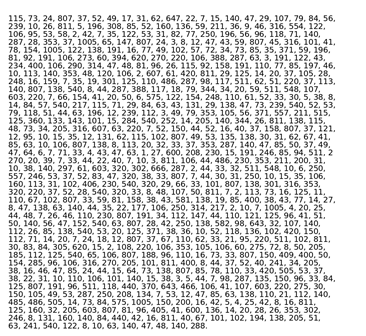

Graphing random variables

The possible values and associated probabilities for a random variable can

be easily visualized through a graph. For instance, consider the random

variable X from the previous

section with an outcome set of \{1, 2\}, and Pr [X = 1] = 0.5 and Pr [X = 2] = 0.5. We

would typically display such a random variable in the form of a bar graph as

in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Random variable X

The wide bars in Figure 1 obviously do not mean to suggest that the

random variable X is actually

continuous. Instead, the bars are made wide in order to be more visually appealing

(just a line straight up provides a less intuitive visualization).

Uniform variables

In the expression “random variable,” the term “random” just means “probabilistic”. In other words, it just means that two or more possible outcomes of the variable occur with certain probabilities. These outcomes, however, do not necessarily have to be equally likely (though the term “random” can indeed have that meaning in other contexts).

A uniform variable is a special case of a random variable.

It can take on two or more values all with an equal probability. The random

variable X depicted in Figure 1 is clearly a uniform variable, as both possible outcomes occur with a

probability 0.5. There are,

however, many random variables that are not instances of uniform variables.

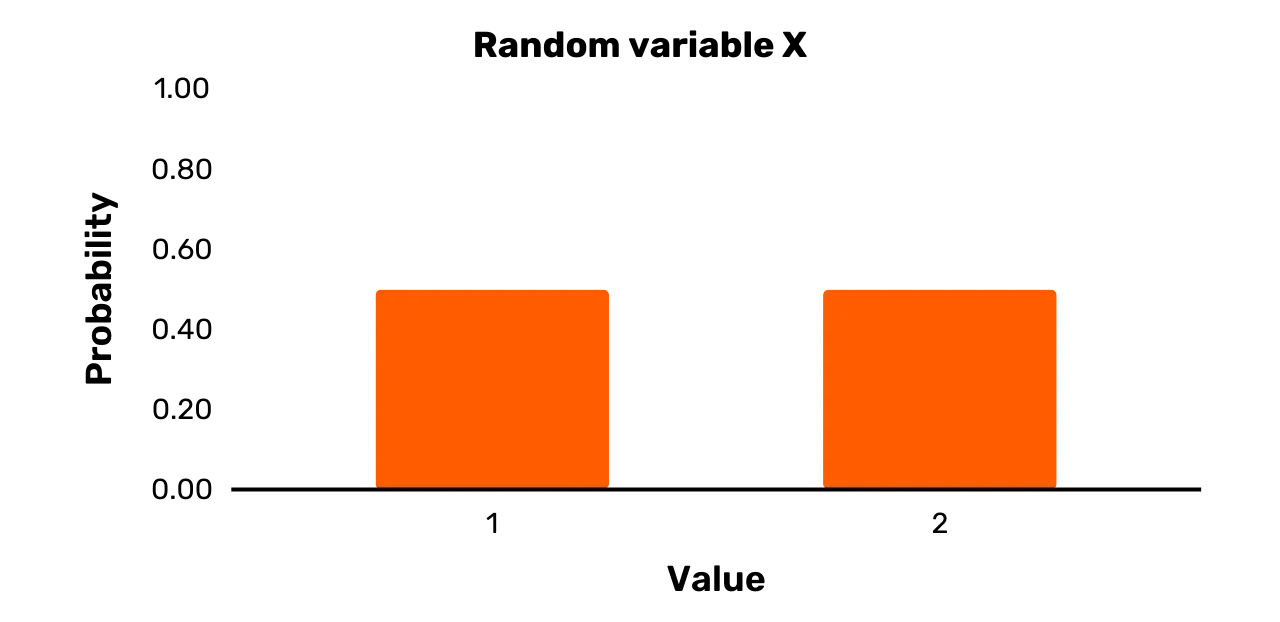

Consider, for example, the random variable Y. It has an outcome set {1, 2, 3, 8, 10} and the following

probability distribution:

\Pr[Y = 1] = 0.25\Pr[Y = 2] = 0.35\Pr[Y = 3] = 0.1\Pr[Y = 8] = 0.25\Pr[Y = 10] = 0.05While two possible outcomes indeed have an equal probability of occurring,

namely 1 and 8, Y can also take on certain values with different probabilities than 0.25 upon sampling. Hence, while Y is indeed a random variable, it is not a uniform variable.

A graphical depiction of Y is

provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Random variable Y

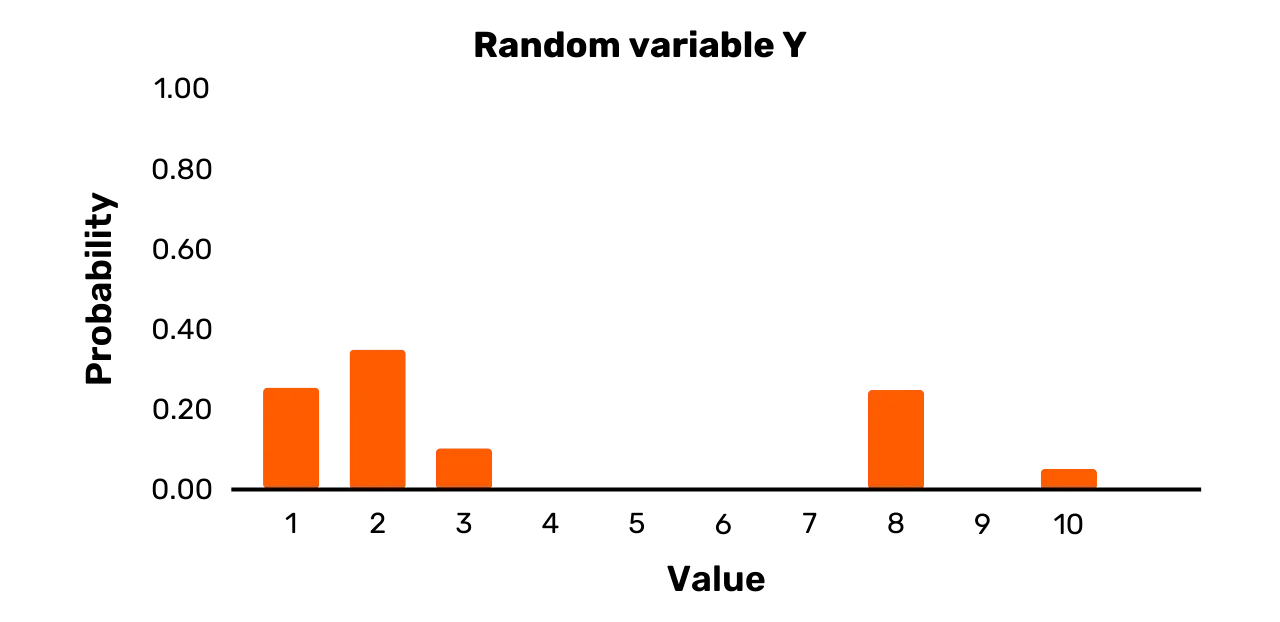

For a final example, consider the random variable Z. It has the outcome set {1,3,7,11,12} and the following probability distribution:

\Pr[Z = 2] = 0.2\Pr[Z = 3] = 0.2\Pr[Z = 9] = 0.2\Pr[Z = 11] = 0.2\Pr[Z = 12] = 0.2You can see it depicted in Figure 3. The random variable Z is, in contrast to Y, a uniform variable, as all the probabilities for the possible values upon sampling are equal.

Figure 3: Random variable Z

Conditional probability

Suppose that Bob intends to uniformly select a day from the last calendar year. What should we conclude is the probability of the selected day being in Summer?

As long as we think Bob’s process will indeed be truly uniform, we should conclude that there is a 1/4 probability Bob selects a day in Summer. This is the unconditional probability of the randomly selected day being in Summer.

Suppose now that instead of uniformly drawing a calendar day, Bob only selects uniformly from among those days on which the noon temperature at Crystal Lake (New Jersey) was 21 degrees Celcius or higher. Given this additional information, what can we conclude about the probability that Bob will select a day in Summer?

We should really draw a different conclusion than before, even without any further specific information (e.g., the temperature at noon each day last calendar year).

Knowing that Crystal Lake is in New Jersey, we would certainly not expect the temperature at noon to be 21 degrees Celsius or higher in Winter. Instead, it is much more likely to be a warm day in the Spring or Fall, or a day somewhere in the Summer. Hence, knowing the noon temperature at Crystal Lake on the selected day was 21 degrees Celsius or higher, the probability that the day selected by Bob is in the Summer becomes much higher. This is the conditional probability of the randomly selected day being in Summer, given that the noon temperature at Crystal Lake was 21 degrees Celsius or higher.

Unlike in the previous example, the probabilities of two events can also be completely unrelated. In that case, we say that they are independent.

Suppose, for example, that a certain fair coin has landed heads. Given this fact, what, then, is the probability that it will rain tomorrow? The conditional probability in this case should be the same as the unconditional probability that it will rain tomorrow, as a coin flip does not generally have any impact on the weather.

We use a "|" symbol for writing out conditional probability statements. For

instance, the probability of event A given that event B has transpired

can be written as follows:

Pr[A|B]So, when two events, A and B, are independent, then:

Pr[A|B] = Pr[A] \text{ and } Pr[B|A] = Pr[B]The condition for independence can be simplified as follows:

Pr[A, B] = Pr[A] \cdot Pr[B]A key result in probability theory is known as Bayes Theorem. It basically states that Pr[A|B] can be rewritten as follows:

Pr[A|B] = \frac{Pr[B|A] \cdot Pr[A]}{Pr[B]}Instead of using conditional probabilities with specific events, we can also

look at the conditional probabilities involved with two or more random

variables over a set of possible events. Suppose two random variables, X and Y. We can denote any

possible value for X by x, and any possible value for Y by y. We might say, then,

that two random variables are independent if the following statement holds:

Pr[X = x, Y = y] = Pr[X = x] \cdot Pr[Y = y]for all x and y.

Let's be a bit more explicit about what this statement means.

Suppose that the outcome sets for X and Y are defined as follows: X = \{x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_i, \ldots, x_n\} and Y = \{y_1, y_2, \ldots, y_i, \ldots, y_m\}. (It is typical to indicate sets of values by bold-faced, upper-case

letters.)

Now suppose you sample Y and

observe y_1. The statement

above tells us that the probability of now obtaining x_1 from sampling X is exactly

the same as if we had never observed y_1. This is true for any y_i we could have drawn from our initial sampling of Y. Finally, this holds true

not just for x_1. For any x_i, the probability of

occurring is not influenced by the outcome of a sampling of Y. All this also applies to

the case where X is sampled first.

Let's end our discussion on a slightly more philosophical point. In any real-world situation, the probability of some event is always assessed against a particular set of information. There is no “unconditional probability” in any very strict sense of the word.

For instance, suppose I asked you for the probability that pigs will fly by 2030. Though I give you no further information, you clearly know a lot about the world that can influence your judgment. You have never seen pigs fly. You know that most people will not expect them to fly. You know that they are not really built to fly. And so on.

Hence, when we speak of an “unconditional probability” of some event in a real-world context, that term really can only have meaning if we take it to mean something like “the probability without any further explicit information”. Any understanding of a “conditional probability” should, then, always be understood against some specific piece of information.

I might, for instance, ask you the probability that pigs will fly by 2030, after giving you evidence that some goats in New Zealand have learned to fly after a few years of training. In this case, you will probably adjust your judgment of the probability that pigs will fly by 2030. So the probability that pigs will fly by 2030 is conditional upon this evidence about goats in New Zealand.

The modulo operation

Modulo

The most basic expression with the modulo operation is of

the following form: x \mod y.

The variable x is called the

dividend and the variable y the

divisor. To perform a modulo operation with a positive dividend and a positive

divisor, you just determine the remainder of the division.

For instance, consider the expression 25 \mod 4. The number 4 goes into the number 25 a total of 6 times. The remainder of

that division is 1. Hence, 25 \mod 4 equals 1. In a similar

manner, we can evaluate the expressions below:

29 \mod 30 = 29(as 30 goes into 29 a total of 0 times and the remainder is 29)42 \mod 2 = 0(as 2 goes into 42 a total of 21 times and the remainder is 0)12 \mod 5 = 2(as 5 goes into 12 a total of 2 times and the remainder is 2)20 \mod 8 = 4(as 8 goes into 20 a total of 2 times and the remainder is 4)

When the dividend or divisor is negative, modulo operations can be handled differently by programming languages.

You will definitely come across cases with a negative dividend in cryptography. In these cases, the typical approach is as follows:

- First determine the closest value lower than or equal to the

dividend into which the divisor divides with a remainder of zero. Call

that value

p. - If the dividend is

x, then the result of the modulo operation is the value ofx – p.

For instance, suppose that the dividend is –20 and the divisor 3. The closest value lower than or equal to –20 into which 3 divides evenly is –21. The value of x – p in this case is –20 – (–21).

This equals 1 and, hence, –20 \mod 3 equals 1. In a similar

manner, we can evaluate the expressions below:

–8 \mod 5 = 2–19 \mod 16 = 13–14 \mod 6 = 4

Regarding notation, you will typically see the following types of

expressions: x = [y \mod z].

Due to the brackets, the modulo operation in this case only applies to the

right-hand side of the expression. If y equals 25 and z equals 4, for

example, then x evaluates to 1.

Without brackets, the modulo operation acts on both sides of an

expression. Suppose, for instance, the following expression: x = y \mod z. If y equals 25 and z equals 4,

then all we know is that x \mod 4 evaluates to 1. This is consistent with any value for x from the set \{\ldots,–7, –3, 1, 5, 9,\ldots\}.

The branch of mathematics that involves modulo operations on numbers and expressions is referred to modular arithmetic. You can think of this branch as arithmetic for cases in which the number line is not infinitely long. Though we typically come across modulo operations for (positive) integers within cryptography, you can also perform modulo operations using any real numbers.

The shift cipher

The modulo operation is frequently encountered within cryptography. To illustrate, let's consider one of the most famous historical encryption schemes: the shift cipher.

Let's first define it. Suppose a dictionary D that equates all the

letters of the English alphabet, in order, with the set of numbers \{0, 1, 2, \ldots, 25\}. Assume a message space M. The shift cipher is, then, an encryption scheme defined as follows:

- Select uniformly a key

kout of the key space K, where K =\{0, 1, 2, \ldots, 25\}[1] - Encrypt a message

m \in \mathbf{M}, as follows:- Separate

minto its individual lettersm_0, m_1, \ldots, m_i, \ldots, m_l - Convert each

m_ito a number according to D - For each

m_i,c_i = [(m_i + k) \mod 26] - Convert each

c_ito a letter according to D - Then combine

c_0, c_1, \ldots, c_lto yield the ciphertextc

- Separate

- Decrypt a ciphertext

cas follows:- Convert each

c_ito a number according to D - For each

c_i,m_i = [(c_i – k) \mod 26] - Convert each

m_ito a letter according to D - Then combine

m_0, m_1, \ldots, m_lto yield the original messagem

- Convert each

The modulo operator in the shift cipher ensures that letters wrap around, so that all ciphertext letters are defined. To illustrate, consider the application of the shift cipher on the word “DOG”.

Suppose that you uniformly selected a key to have the value of 17. The

letter “O” equates to 15. Without the modulo operation, the addition of this

plaintext number with the key would amount to a ciphertext number of 32.

However, that ciphertext number cannot be turned into a ciphertext letter,

as the English alphabet only has 26 letters. The modulo operation ensures

that the ciphertext number is actually 6 (the result of 32 \mod 26), which equates to the ciphertext letter “G”.

The entire encryption of the word “DOG” with a key value of 17 is as follows:

- Message = DOG = D,O,G = 3,15,6

c_0 = [(3 + 17) \mod 26] = [(20) \mod 26] = 20 = Uc_1 = [(15 + 17) \mod 26] = [(32) \mod 26] = 6 = Gc_2 = [(6 + 17) \mod 26] = [(23) \mod 26] = 23 = Xc = UGX

Everyone can intuitively understand how the shift cipher works and probably use it themselves. For advancing your knowledge of cryptography, however, it is important to start becoming more comfortable with formalization, as the schemes will become much more difficult. Hence, why the steps for the shift cipher were formalized.

Notes:

[1] We can define this statement exactly, using the terminology from the

previous section. Let a uniform variable K have K as its set of possible

outcomes. So:

Pr[K = 0] = \frac{1}{26}Pr[K = 1] = \frac{1}{26}...and so on. Sample the uniform variable K once to yield a particular key.

The XOR operation

All computer data is processed, stored, and sent across networks at the level of bits. Any cryptographic schemes that are applied to computer data also operate at the bit-level.

For instance, suppose that you have typed an e-mail into your e-mail application. Any encryption you apply does not occur on the ASCII characters of your e-mail directly. Instead, it is applied to the bit-representation of the letters and other symbols in your e-mail.

A key mathematical operation to understand for modern cryptography, besides

the modulo operation, is that of the XOR operation, or

“exclusive or” operation. This operation takes as inputs two bits and yields

as output another bit. The XOR operation will simply be denoted as "XOR". It

yields 0 if the two bits are the same and 1 if the two bits are different.

You can see the four possibilities below. The symbol \oplus represents "XOR" :

0 \oplus 0 = 00 \oplus 1 = 11 \oplus 0 = 11 \oplus 1 = 0

To illustrate, suppose that you have a message m_1 (01111001) and a message m_2 (01011001).

The XOR operation of these two messages can be seen below.

m_1 \oplus m_2 = 01111001 \oplus 01011001 = 00100000

The process is straightforward. You first XOR the left-most bits of m_1 and m_2. In this case that is 0 \oplus 0 = 0. You then XOR

the second pair of bits from the left. In this case that is 1 \oplus 1 = 0. You continue

this process until you have performed the XOR operation on the right-most

bits.

It is easy to see that the XOR operation is commutative, namely that m_1 \oplus m_2 = m_2 \oplus m_1. In addition, the XOR operation is also associative. That is, (m_1 \oplus m_2) \oplus m_3 = m_1 \oplus (m_2 \oplus m_3).

An XOR operation on two strings of alternative lengths can have different interpretations, depending on the context. We will not concern ourselves here with any XOR operations on strings of different lengths.

An XOR operation is equivalent to the special case of performing a modulo operation on the addition of bits when the divisor is 2. You can see the equivalency in the following results:

(0 + 0) \mod 2 = 0 \oplus 0 = 0(1 + 0) \mod 2 = 1 \oplus 0 = 1(0 + 1) \mod 2 = 0 \oplus 1 = 1(1 + 1) \mod 2 = 1 \oplus 1 = 0

Pseudorandomness

In our discussion of random and uniform variables, we drew a specific distinction between “random” and “uniform”. That distinction is typically maintained in practice when describing random variables. However, in our current context, this distinction needs to be dropped and “random” and “uniform” are used synonymously. I will explain why at the end of the section.

To start, we can call a binary string of length n random (or uniform), if it was the

result of sampling a uniform variable S which gives each binary string of such a length n an equal probability of selection.

Suppose, for instance, the set of all binary strings with length 8: \{0000\ 0000, 0000\ 0001, \ldots, 1111\ 1111\}. (It is typical to write an 8-bit string in two quartets, each called a nibble.) Let's call this set of strings S_8.

Per the definition above, we can, then, call a particular binary string of

length 8 random (or uniform), if it was the result of sampling a uniform

variable S that gives each

string in S_8 an equal probability of selection. Given that the set S_8 includes 2^8 elements, the

probability of selection upon sampling would have to be 1/2^8 for each string in the set.

A key aspect to the randomness of a binary string is that it is defined with reference to the process by which it was selected. The form of any particular binary string on its own, therefore, reveals nothing about its randomness in selection.

For example, many people intuitively have the idea that a string like 1111\ 1111 could not have been selected randomly. But this is clearly false.

Defining a uniform variable S over all the binary strings of length 8, the likelihood of selecting 1111\ 1111 from the set S_8 is the same as that of a string such as 0111\ 0100. Thus, you cannot

tell anything about the randomness of a string, just by analyzing the string

itself.

We can also speak of random strings without specifically meaning binary

strings. We might, for instance, speak of a random hex string AF\ 02\ 82. In this case, the string would have been selected at random from the set

of all hex strings of length 6. This is equivalent to randomly selecting a

binary string of length 24, as each hex digit represents 4 bits.

Typically the expression “a random string”, without qualification, refers to

a string randomly selected from the set of all strings with the same length.

This is how I have described it above. A string of length n can, of course, also be randomly selected from a different set. One, for

example, that only constitutes a subset of all the strings of length n, or perhaps a set that

includes strings of varying length. In those cases, however, we would not

refer to it as a “random string”, but rather “a string that is randomly

selected from some set S”.

A key concept within cryptography is that of pseudorandomness. A pseudorandom string of length n appears as if it was the result of sampling a uniform variable S that gives each string in S_n an equal probability of selection. In fact, however, the string is the

result of sampling a uniform variable S' that only defines a probability distribution—not necessarily one with equal

probabilities for all possible outcomes—on a subset of S_n. The

crucial point here is that no one can really distinguish between samples

from S and S', even if you take many of

them.

Suppose, for instance, a random variable S. Its outcome set is S_{256}, this is the set of all binary strings of length 256. This set has 2^{256} elements. Each element has an equal probability of selection, 1/2^{256}, upon

sampling.

In addition, suppose a random variable S'. Its outcome set only includes 2^{128} binary strings

of length 256. It has some probability distribution over those strings, but this

distribution is not necessarily uniform.

Suppose that I now took 1000s of samples from S and 1000s of samples from S' and gave the two sets of outcomes to you. I tell you which set of outcomes

is associated with which random variable. Next, I take a sample from one of

the two random variables. But this time I do not tell you which random

variable I sample. If S' were

pseudorandom, then the idea is that your probability of making the right

guess as to which random variable I sampled is practically no better than 1/2.

Typically, a pseudorandom string of length n is produced by randomly selecting a string of size n – x, where x is a positive integer, and using it as an input for an expansionary

algorithm. This random string of size n – x is known as the seed.

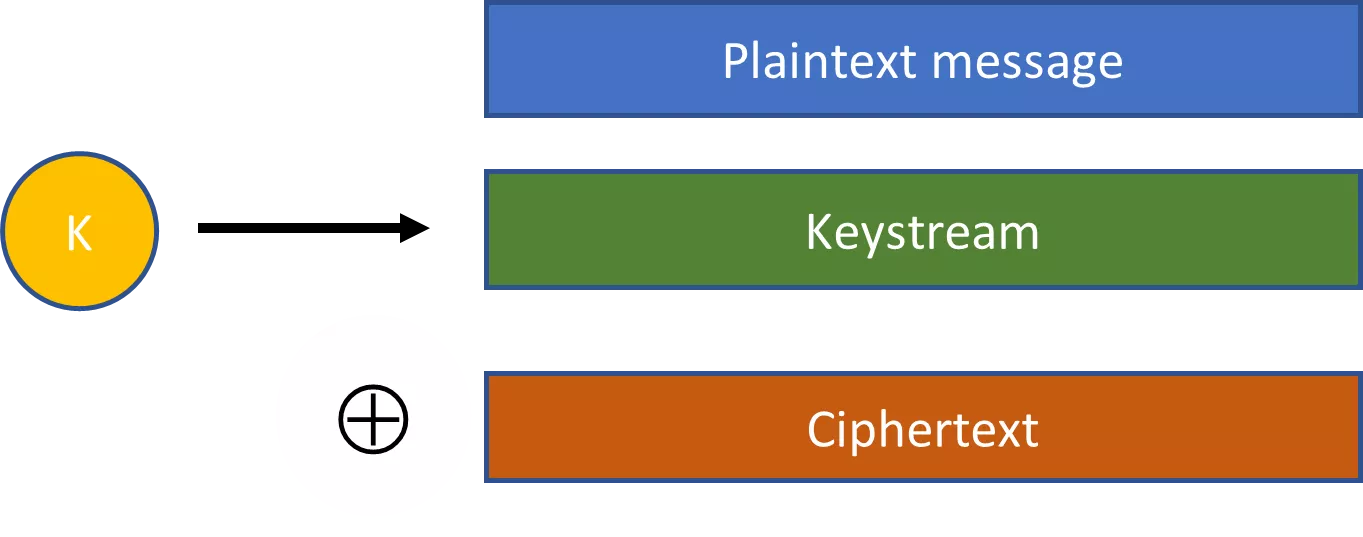

Pseudorandom strings are a key concept to making cryptography practical. Consider, for instance, stream ciphers. With a stream cipher, a randomly selected key is plugged into an expansionary algorithm to produce a much larger pseudorandom string. This pseudorandom string is then combined with the plaintext via an XOR operation to produce a ciphertext.

If we were unable to produce this type of pseudorandom string for a stream cipher, then we would need a key that is as long as the message for its security. This is not a very practical option in most cases.

The notion of pseudorandomness discussed in this section can be defined more formally. It also extends to other contexts. But we need not delve into that discussion here. All you really need to intuitively understand for much of cryptography is the difference between a random and a pseudorandom string. [2]

The reason for dropping the distinction between “random” and “uniform” in

our discussion should now also be clear. In practice, everyone uses the term

pseudorandom to indicate a string that appears as if it was

the result of sampling a uniform variable S. Strictly speaking, we

should call such a string “pseudo-uniform,” adopting our language from

earlier. As the term “pseudo-uniform” is both clunky and not used by anyone,

we will not introduce it here for clarity. Instead, we just drop the

distinction between “random” and “uniform” in the current context.

Notes

[2] If interested in a more formal exposition on these matters, you can consult Katz and Lindell’s Introduction to Modern Cryptography, esp. chapter 3.

Mathematical Foundations of Cryptography 2

What is number theory?

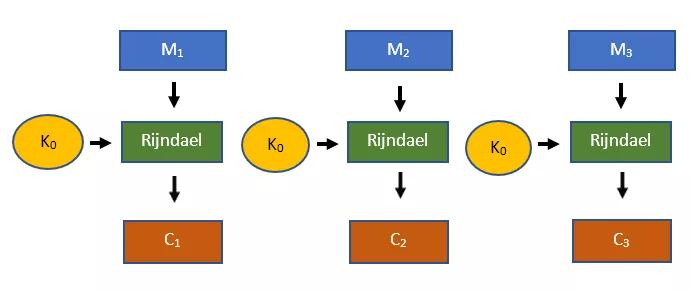

This chapter covers a more advanced topic on the mathematical foundations of cryptography: number theory. Though number theory is important to symmetric cryptography (such as in the Rijndael Cipher), it is particularly important in the public key cryptographic setting.

If you are finding the details of number theory cumbersome, I would recommend a high-level reading the first time around. You can always come back to it at a later point.

You might characterize number theory as the study of the properties of integers and mathematical functions that work with integers.

Consider, for example, that any two numbers a and N are coprimes (or relative primes) if their greatest common divisor

equals 1. Suppose now a particular integer N. How many integers smaller

than N are coprimes with N? Can we make general

statements about the answers to this question? These are the typical types

of questions that number theory seeks to answer.

Modern number theory relies on the tools of abstract algebra. The field of abstract algebra is a subdiscipline of mathematics where the main objects of analysis are abstract objects known as algebraic structures. An algebraic structure is a set of elements conjoined with one or more operations, which meets certain axioms. Through algebraic structures, mathematicians can gain insights into specific mathematical problems, by abstracting away from their details.

The field of abstract algebra is sometimes also called modern algebra. You may also come across the concept of abstract mathematics (or pure mathematics). This latter term is not a reference to abstract algebra, but rather means the study of mathematics for its own sake, and not just with an eye on potential applications.

The sets from abstract algebra can deal with many types of objects, from the shape-preserving transformations on an equilateral triangle to wallpaper patterns. For number theory, we only consider sets of elements that contain integers or functions that work with integers.

Groups

A basic concept in mathematics is that of a set of elements. A set is usually denoted by accolade signs with the elements separated by commas.

For instance, the set of all integers is \{…, -2, -1, 0, 1, 2, …\}. The ellipses here mean that a certain pattern continues in a particular

direction. So the set of all integers also includes 3, 4, 5, 6 and so on, as well as -3, -4, -5, -6 and so on. This set of all integers is typically denoted by \mathbb{Z}.

Another example of a set is \mathbb{Z} \mod 11, or the set of all integers modulo 11. In contrast to the entire set \mathbb{Z}, this

set only contains a finite number of elements, namely \{0, 1, \ldots, 9, 10\}.

A common mistake is to think that the set \mathbb{Z} \mod 11 actually is \{-10, -9, \ldots, 0, \ldots, 9, 10\}. But this is not the case, given the way we defined the modulo operation

earlier. Any negative integers reduced by modulo 11 wrap onto \{0, 1, \ldots, 9, 10\}. For instance, the expression -2 \mod 11 wraps around to 9, while the

expression -27 \mod 11 wraps

around to 5.

Another basic concept in mathematics is that of a binary operation. This is any operation that takes two elements to produce a third. For instance, from basic arithmetic and algebra, you would be familiar with four fundamental binary operations: addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

These two basic mathematical concepts, sets and binary operations, are used to define the notion of a group, the most essential structure in abstract algebra.

Specifically, suppose some binary operation \circ. In addition, suppose some set of elements S equipped

with that operation. All “equipped” means here is that the operation \circ can be performed between any two elements in the set S.

The combination \langle \mathbf{S}, \circ \rangle is, then, a group if it meets four specific conditions, known

as the group axioms.

- For any

aandbthat are elements of\mathbf{S},a \circ bis also an element of\mathbf{S}. This is known as the closure condition. - For any

a,b, andcthat are elements of\mathbf{S}, it is the case that(a \circ b) \circ c = a \circ (b \circ c). This is known as the associativity condition. - There is a unique element

ein\mathbf{S}, such that for every elementain\mathbf{S}, the following equation holds:e \circ a = a \circ e = a. As there is only one such elemente, it is called the identity element. This condition is known as the identity condition. - For each element

ain\mathbf{S}, there exists an elementbin\mathbf{S}, such that the following equation holds:a \circ b = b \circ a = e, whereeis the identity element. Elementbhere is known as the inverse element, and it is commonly denoted asa^{-1}. This condition is known as the inverse condition or the invertibility condition.

Let's explore groups a little further. Denote the set of all integers by \mathbb{Z}. This set combined with standard addition, or \langle \mathbb{Z}, + \rangle, clearly fits the definition of a group, as it meets the four axioms

above.

- For any

xandythat are elements of\mathbb{Z},x + yis also an element of\mathbb{Z}. So\langle \mathbb{Z}, + \ranglemeets the closure condition. - For any

x,y, andzthat are elements of\mathbb{Z},(x + y) + z = x + (y + z). So\langle \mathbb{Z}, + \ranglemeets the associativity condition. - There is an identity element in

\langle \mathbb{Z}, + \rangle, namely 0. For anyxin\mathbb{Z}, it namely holds that:0 + x = x + 0 = x. So\langle \mathbb{Z}, + \ranglemeets the identity condition. - Finally, for each element

xin\mathbb{Z}, there is ayso thatx + y = y + x = 0. Ifxwere 10, for instance,ywould be-10(in the case thatxis 0,yis also 0). So\langle \mathbb{Z}, + \ranglemeets the inverse condition.

Importantly, that the set of integers with addition constitutes a group does

not mean that it constitutes a group with multiplication. You can verify

this by testing \langle \mathbb{Z}, \cdot \rangle against the four group axioms (where \cdot means standard multiplication).

The first two axioms obviously hold. In addition, under multiplication the

element 1 can serve as the identity element. Any integer x multiplied by 1, namely yields x. However, \langle \mathbb{Z}, \cdot \rangle does not meet the inverse condition. That is, there is not a unique element y in \mathbb{Z} for

every x in \mathbb{Z}, so that x \cdot y = 1.

For instance, suppose that x = 22. What value y from the set \mathbb{Z} multiplied with x would yield

the identity element 1? The value of 1/22 would work, but this is not in the set \mathbb{Z}. In

fact, you run into this problem for any integer x, other than the values of 1

and -1 (where y would have to

be 1 and -1 respectively).

If we allowed real numbers for our set, then our problems largely disappear.

For any element x in the set,

multiplication by 1/x yields 1.

As fractions are included in the set of real numbers, an inverse can be found

for every real number. The exception is zero, as any multiplication with zero

will never yield the identity element 1. Hence, the set of non-zero real numbers

equipped with multiplication is indeed a group.

Some groups meet a fifth general condition, known as the commutativity condition. This condition is as follows:

- Suppose a group

Gwith a set S and a binary operator\circ. Suppose thataandbare elements of S. If it is the case thata \circ b = b \circ afor any two elementsaandbin S, thenGmeets the commutativity condition.

Any group that meets the commutativity condition is known as a commutative group, or an Abelian group (after Niels Henrik Abel). It is easy to verify that both the set of real numbers over addition and the set of integers over addition are Abelian groups. The set of integers over multiplication is not a group at all, so ipso facto cannot be an Abelian group. The set of non-zero real numbers over multiplication, by contrast, is also an Abelian group.

You should heed two important conventions on notation. First, the signs “+” or “×” will frequently be employed to symbolize group operations, even when the elements are not, in fact, numbers. In these cases, you should not interpret these signs as standard arithmetic addition or multiplication. Instead, they are operations with only an abstract similarity to these arithmetic operations.

Unless you are specifically referring to arithmetic addition or

multiplication, it is easier to use symbols such as \circ and \diamond for group operations,

as these do not have very culturally ingrained connotations.

Second, for the same reason that “+” and “×” are often used for indicating

non-arithmetic operations, the identity elements of groups are frequently

symbolized by “0” and “1”, even when the elements in these groups are not

numbers. Unless you are referring to the identity element of a group with

numbers, it is easier to use a more neutral symbol such as “e” to indicate the identity element.

Many different and very important sets of values in mathematics equipped with certain binary operations are groups. Cryptographic applications, however, only work with sets of integers or at least elements that are described by integers, that is, within the domain of number theory. Hence, sets with real numbers other than integers are not employed in cryptographic applications.

Let's finish by providing an example of elements that can be “described by integers”, even though they are not integers. A good example is the points of elliptic curves. Though any point on an elliptic curve is clearly not an integer, such a point is indeed described by two integers.

Elliptic curves are, for instance, crucial to Bitcoin. Any standard Bitcoin private and public key pair is selected from the set of points that is defined by the following elliptic curve:

x^3 + 7 = y^2 \mod 2^{256} – 2^{32} – 29 – 28 – 27 – 26 - 24 - 1(the largest prime number less than 2^{256}). The x-coordinate is the

private key and the y-coordinate is your public

key.

Transactions in Bitcoin typically involve locking outputs to one or more public keys in some way. The value from these transactions can, then, be unlocked making digital signatures with the corresponding private keys.

Cyclic groups

A major distinction we can draw is between a finite and an infinite group. The former has a finite number of elements, while the latter has an infinite number of elements. The number of elements in any finite group is known as the order of the group. All practical cryptography that involves the use of groups relies on finite (number-theoretic) groups.

Within public key cryptography, a certain class of finite Abelian groups known as cyclic groups are particularly important. In order to understand cyclic groups, we first need to understand the concept of group element exponentiation.

Suppose a group G with a

group operation \circ, and

that a is an element of G. The expression a^n should, then, be interpreted as the element a combined with itself a total of n – 1 times. For instance, a^2 means a \circ a, a^3 means a \circ a \circ a, and

so on. (Note that exponentiation here is not necessarily exponentiation in

the standard arithmetic sense.)

Let's turn to an example. Suppose that G = \langle \mathbb{Z} \mod 7, + \rangle, and that our value for a equals 4. In this case, a^2 = [4 + 4 \mod 7] = [8 \mod 7] = 1 \mod 7. Alternatively, a^4 would

represent [4 + 4 + 4 + 4 \mod 7] = [16 \mod 7] = 2 \mod 7.

Some Abelian groups have one or more elements, which can yield all other group elements through continued exponentiation. These elements are called generators or primitive elements.

An important class of such groups is \langle \mathbb{Z}^* \mod N, \cdot \rangle, where N is a prime number.

The notation \mathbb{Z}^* here means that the group contains all non-zero, positive integers less than N. Such a group, therefore,

always has N – 1 elements.

Consider, for instance, G = \langle \mathbb{Z}^* \mod 11, \cdot \rangle. This group has the following elements: \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10\}. The order of this group is 10 (which is indeed equal to 11 – 1).

Let's explore exponentiating the element 2 from this group. The calculations

up until 2^{12} are

shown below. Note that on the left side of the equation, the exponent refers

to group element exponentiation. In our particular example, this indeed involves

arithmetic exponentiation on the right side of the equation (but it could have

also involved, for instance, addition). To clarify, I have written out the repeated

operation, rather than the exponent form on the right side.

2^1 = 2 \mod 112^2 = 2 \cdot 2 \mod 11 = 4 \mod 112^3 = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \mod 11 = 8 \mod 112^4 = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \mod 11 = 16 \mod 11 = 5 \mod 112^5 = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \mod 11 = 32 \mod 11 = 10 \mod 112^6 = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \mod 11 = 64 \mod 11 = 9 \mod 112^7 = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \mod 11 = 128 \mod 11 = 7 \mod 112^8 = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \mod 11 = 256 \mod 11 = 3 \mod 112^9 = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \mod 11 = 512 \mod 11 = 6 \mod 112^{10} = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \mod 11 = 1024 \mod 11 = 1 \mod 112^{11} = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \mod 11 = 2048 \mod 11 = 2 \mod 112^{12} = 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \mod 11 = 4096 \mod 11 = 4 \mod 11

If you look carefully, you can see that performing exponentiation on the

element 2 cycles through all the elements of \langle \mathbb{Z}^* \mod 11, \cdot \rangle in the following order: 2, 4, 8, 5, 10, 9, 7, 3, 6, 1. After 2^{10}, continued

exponentiation of the element 2 cycles through all the elements again and in

the same order. Hence, the element 2 is a generator in \langle \mathbb{Z}^* \mod 11, \cdot \rangle.

Though \langle \mathbb{Z}^* \mod 11, \cdot \rangle has multiple generators, not all the elements of this group are generators.

Consider, for example, the element 3. Running through the first 10 exponentiations,

without showing the cumbersome calculations, yields the following results:

3^1 = 3 \mod 113^2 = 9 \mod 113^3 = 5 \mod 113^4 = 4 \mod 113^5 = 1 \mod 113^6 = 3 \mod 113^7 = 9 \mod 113^8 = 5 \mod 113^9 = 4 \mod 113^{10} = 1 \mod 11

Instead of cycling through all the values in \langle \mathbb{Z}^* \mod 11, \cdot \rangle, exponentiation of the element 3 only leads to a subset of those values:

3, 9, 5, 4, and 1. After the fifth exponentiation, these values start

repeating.

We can now define a cyclic group as any group with at least one generator. That is, there is at least one group element from which you can produce all other group elements through exponentiation.

You may have noticed in our example above that both 2^{10} and 3^{10} equal 1 \mod 11. In fact, though we

will not perform the calculations, the exponentiation by 10 of any element

in the group \langle \mathbb{Z}^* \mod 11, \cdot \rangle will yield 1 \mod 11. Why is

this the case?

This is an important question, but it takes some work to answer.

To start, suppose two positive integers a and N. An important theorem

in number theory states that a has a multiplicative inverse modulo N (that is, an integer b so

that a \cdot b = 1 \mod N) if

and only if the greatest common divisor between a and N equals 1. That is, if a and N are coprimes.

So, for any group of integers equipped with multiplication modulo N, only the smaller coprimes with N are included in the set. We can denote this set by \mathbb{Z}^c \mod N.

For instance, suppose that N is 10. Only the integers 1, 3, 7, and 9 are coprimes with 10. So the set \mathbb{Z}^c \mod 10 only includes \{1, 3, 7, 9\}. You

cannot create a group with integer multiplication modulo 10 using any other

integers between 1 and 10. For this particular group, the inverses are the

pairs 1 and 9, and 3 and 7.

In the case where N itself is

prime, all the integers from 1 through N – 1 are coprimes with N. Such a

group, thus, has an order of N – 1. Using our earlier

notation, \mathbb{Z}^c \mod N equals \mathbb{Z}^* \mod N when N is prime. The group we

selected for our earlier example, \langle \mathbb{Z}^* \mod 11, \cdot \rangle, is a particular instance of this class of groups.

Next, the function \phi(N) calculates the number of coprimes up until a number N, and is known as Euler’s Phi function. [1] According to Euler’s Theorem, whenever two integers a and N are coprimes, the following

holds:

a^{\phi(N)} \mod N = 1 \mod N

This has an important implication for the class of groups \langle \mathbb{Z}^* \mod N, \cdot \rangle where N is prime. For these

groups, group element exponentiation represents arithmetic exponentiation.

That is, a^{\phi(N)} \mod N represents the arithmetic operation a^{\phi(N)} \mod N.

As any element a in these

multiplicative groups is coprime with N, it means that a^{\phi(N)} \mod N = a^{N – 1} \mod N = 1 \mod N.

Euler’s theorem is a really important result. To start, it implies that all

elements in \langle \mathbb{Z}^* \mod N, \cdot \rangle can only cycle through a number of values by exponentiation that divides

into N – 1. In the case of \langle \mathbb{Z}^* \mod 11, \cdot \rangle, this means that each element can only cycle through 2, 5, or 10 elements.

The group values that any element cycles through upon exponentiation is

known as the order of the element. An element with an order

equivalent to the order of a group is a generator.

Furthermore, Euler’s theorem implies that we can always know the result of a^{N – 1} \mod N for any group \langle \mathbb{Z}^* \mod N, \cdot \rangle where N is prime. This is so regardless

of how complicated the actual calculations might be.

For instance, suppose our group is \mathbb{Z}^* \mod 160,481,182 (where 160,481,182 is indeed a prime number). We know that all integers 1

through 160,481,181 must be elements of this group, and that \phi(n) = 160,481,181. Though

we cannot make all the steps in the calculations, we know that expressions

such as 514^{160,481,181}, 2,005^{160,481,181}, and 256,212^{160,481,181} must all evaluate to 1 \mod 160,481,182.

Notes:

[1] The function works as follows. Any integer N can be factored into a product of primes. Suppose that a particular N is factored as follows: p_1^{e1} \cdot p_2^{e2} \cdot \ldots \cdot

p_m^{em} where all the p’s are prime

numbers and all the e’s are

integers greater than or equal to 1. Then:

\phi(N) = \sum_{i=1}^m \left[p_i^{e_i} - p_i^{e_i - 1}\right]Euler's Phi function formula for the prime factorization of N.

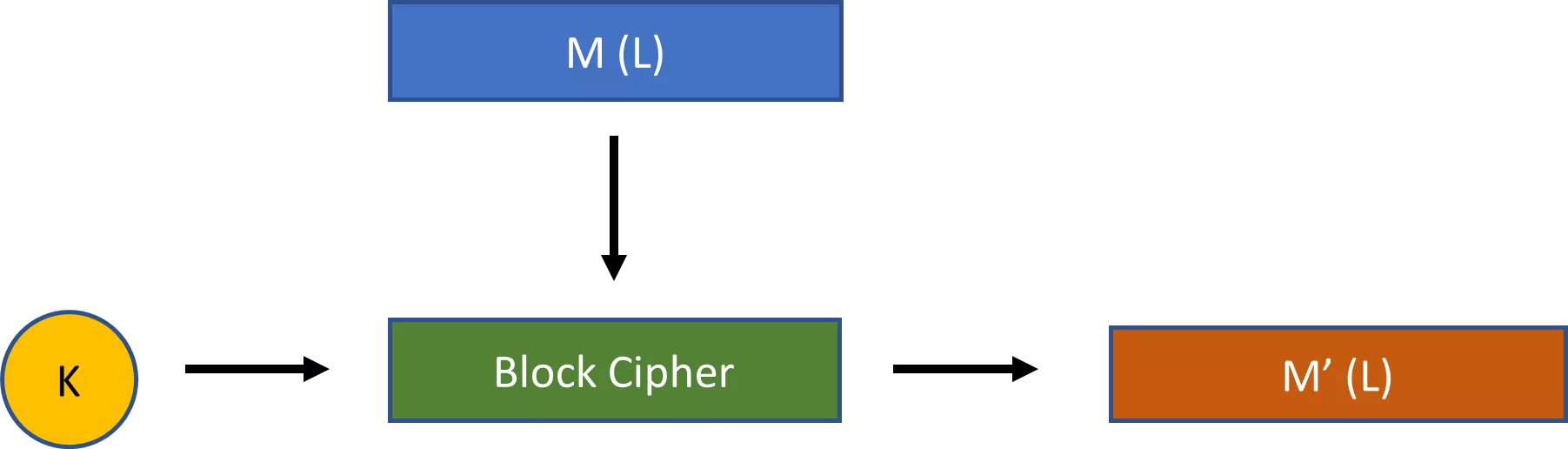

Fields

A group is the basic algebraic structure in abstract algebra, but there are many more. The only other algebraic structure you need to be familiar with is that of a field, specifically that of a finite field. This type of algebraic structure is frequently used in cryptography, such as in the Advanced Encryption Standard. The latter is the main symmetric encryption scheme that you will encounter in practice.

A field is derived from the notion of a group. Specifically, a field is a set of elements S equipped with two binary operators \circ and \diamond, which meets the

following conditions:

- The set S equipped with

\circis an Abelian group. - The set S equipped with

\diamondis an Abelian group for the “non-zero” elements. - The set S equipped with the two operators meets what is

known as the distributive condition: Suppose that

a,b, andcare elements of S. Then S equipped with the two operators meets the distributive property whena \circ (b \diamond c) = (a \circ b) \diamond (a \circ c).

Note that, as with groups, the definition of a field is very abstract. It

makes no claims about the types of elements in S, or about

the operations \circ and \diamond. It just states that

a field is any set of elements with two operations for which the three above

conditions hold. (The “zero” element in the second Abelian group can be

abstractly interpreted.)

So what might be an example of a field? A good example is the set \mathbb{Z} \mod 7, or \{0, 1, \ldots, 7\} defined over standard addition (in place of \circ above) and standard multiplication (in place of \diamond above).

First, \mathbb{Z} \mod 7 meets the condition for being an Abelian group over addition, and it meets

the condition for being an Abelian group over multiplication if you only consider

the non-zero elements. Second, the combination of the set with the two operators

meets the distributive condition.

It is didactically worthwhile to explore these claims by using some

particular values. Let's take the experimental values 5, 2, and 3, some

randomly selected elements from the set \mathbb{Z} \mod 7, to inspect the field \langle \mathbb{Z} \mod 7, +, \cdot \rangle. We will use these three values in order, as needed to explore particular

conditions.

Let’s first explore if \mathbb{Z} \mod 7 equipped with addition is an Abelian group.

- Closure condition: Let’s take 5 and 2 as our values. In

that case,

[5 + 2] \mod 7 = 7 \mod 7 = 0. This is indeed an element of\mathbb{Z} \mod 7, so the result is consistent with the closure condition. - Associativity condition: Let’s take 5, 2, and 3 as our

values. In that case,

[(5 + 2) + 3] \mod 7 = [5 + (2 + 3)] \mod 7 = 10 \mod 7 = 3. This is consistent with the associativity condition. - Identity condition: Let’s take 5 as our value. In that

case,

[5 + 0] \mod 7 = [0 + 5] \mod 7 = 5. So 0 looks to be the identity element for addition. - Inverse condition: Consider the inverse of 5. It needs to

be the case that

[5 + d] \mod 7 = 0, for some value ofd. In this case, the unique value from\mathbb{Z} \mod 7that meets this condition is 2. - Commutativity condition: Let’s take 5 and 3 as our

values. In that case,

[5 + 3] \mod 7 = [3 + 5] \mod 7 = 1. This is consistent with the commutativity condition.

The set \mathbb{Z} \mod 7 equipped with addition clearly appears to be an Abelian group. Let’s now

explore if \mathbb{Z} \mod 7 equipped

with multiplication is an Abelian group for all the non-zero elements.

- Closure condition: Let’s take 5 and 2 as our values. In

that case,

[5 \cdot 2] \mod 7 = 10 \mod 7 = 3. This is also an element of\mathbb{Z} \mod 7, so the result is consistent with the closure condition. - Associativity condition: Let’s take 5, 2, and 3 as our

values. In that case,

[(5 \cdot 2) \cdot 3] \mod 7 = [5 \cdot (2 \cdot 3)] \mod 7 = 30 \mod 7 = 2. This is consistent with the associativity condition. - Identity condition: Let’s take 5 as our value. In that

case,

[5 \cdot 1] \mod 7 = [1 \cdot 5] \mod 7 = 5. So 1 looks to be the identity element for multiplication. - Inverse condition: Consider the inverse of 5. It needs to

be the case that

[5 \cdot d] \mod 7 = 1, for some value ofd. The unique value from\mathbb{Z} \mod 7that meets this condition is 3. This is consistent with the inverse condition. - Commutativity condition: Let’s take 5 and 3 as our

values. In that case,

[5 \cdot 3] \mod 7 = [3 \cdot 5] \mod 7 = 15 \mod 7 = 1. This is consistent with the commutativity condition.

The set \mathbb{Z} \mod 7 clearly seems to meet the rules for being an Abelian group when conjoined with

either addition or multiplication over the non-zero elements.

Finally, this set combined with both operators seems to meet the

distributive condition. Let’s take 5, 2, and 3 as our values. We can see

that [5 \cdot (2 + 3)] \mod 7 = [5 \cdot 2 + 5 \cdot 3] \mod 7 = 25 \mod 7 = 4.

We have now seen that \mathbb{Z} \mod 7 equipped with addition and multiplication meets the axioms for a finite field

when testing with particular values. Of course, we can also show that generally,

but will not do so here.

A key distinction is between two types of fields: finite and infinite fields.

An infinite field involves a field where the set S is infinitely large. The set of real numbers \mathbb{R} equipped with addition and multiplication is an example of an infinite

field. A finite field, also known as a Galois field, is a field where the set S is finite. Our example above of \langle \mathbb{Z} \mod 7, +, \cdot \rangle is a finite field.

In cryptography, we are primarily interested in finite fields. Generally, it

can be shown that a finite field exists for some set of elements S if and only if it has p^m elements, where p is a prime

number and m a positive

integer greater than or equal to one. In other words, if the order of some

set S is a prime number (p^m where m = 1) or some prime

power (p^m where m > 1), then you can find two

operators \circ and \diamond such that the conditions

for a field are satisfied.

If some finite field has a prime number of elements, then it is called a prime field. If the number of elements in the finite field is a prime power, then the field is called an extension field. In cryptography, we are interested in both prime and extension fields. [2]

The main prime fields of interest in cryptography are those where the set of

all integers is modulated by some prime number, and the operators are

standard addition and multiplication. This class of finite fields would

include \mathbb{Z} \mod 2, \mathbb{Z} \mod 3, \mathbb{Z} \mod 5, \mathbb{Z} \mod 7, \mathbb{Z} \mod 11, \mathbb{Z} \mod 13,

and so on. For any prime field \mathbb{Z} \mod p,

the set of integers of the field is as follows: \{0, 1, \ldots, p – 2, p – 1\}.

In cryptography, we are also interested in extension fields, particularly

any fields with 2^m elements

where m > 1. Such finite

fields are, for instance, used in the Rijndael Cipher, which forms the basis

of the Advanced Encryption Standard. While prime fields are relatively

intuitive, these base 2 extension fields are probably not for anyone

unfamiliar with abstract algebra.

To start, it is indeed true that any set of integers with 2^m elements can be assigned two operators that would make their combination a

field (as long as m is a positive

integer). Yet, just because a field exists does not necessarily mean that it

is easy to discover or particularly practical for certain applications.

As it turns out, particularly applicable extension fields of 2^m in cryptography are those defined over particular sets of polynomial expressions,

rather than some set of integers.

For instance, suppose that we wanted an extension field with 2^3 (i.e., 8) elements in the set. While there might be many different sets that

can be used for fields of that size, one such set includes all unique

polynomials of the form a_2x^2 + a_1x + a_0, where

each coefficient a_i is

either 0 or 1. Hence, this set S includes the following elements:

0: The case wherea_2 = 0,a_1 = 0, anda_0 = 0.1: The case wherea_2 = 0,a_1 = 0, anda_0 = 1.x: The case wherea_2 = 0,a_1 = 1, anda_0 = 0.x + 1: The case wherea_2 = 0,a_1 = 1, anda_0 = 1.x^2: The case wherea_2 = 1,a_1 = 0, anda_0 = 0.x^2 + 1: The case wherea_2 = 1,a_1 = 0, anda_0 = 1.x^2 + x: The case wherea_2 = 1,a_1 = 1, anda_0 = 0.x^2 + x + 1: The case wherea_2 = 1,a_1 = 1, anda_0 = 1.

So S would be the set \{0, 1, x, x + 1, x^2, x^2 + 1, x^2 + x, x^2 + x + 1\}. What two operations can be defined over this set of elements to ensure

their combination is a field?

The first operation on the set S (\circ) can be defined as standard polynomial addition modulo 2. All you have to

do is add the polynomials as you normally would, and then apply the modulo 2

to each of the coefficients of the resulting polynomial. Here are some

examples:

[(x^2) + (x^2 + x + 1)] \mod 2 = [2x^2 + x + 1] \mod 2 = x + 1[(x^2 + x) + (x)] \mod 2 = [x^2 + 2x] \mod 2 = x^2[(x + 1) + (x^2 + x + 1)] \mod 2 = [x^2 + 2x + 2] \mod 2 = x^2 + 1

The second operation on the set S (\diamond) that is needed for creating the field is more complicated. It is a kind

of multiplication, but not standard multiplication from arithmetic. Instead,

you have to see each element as a vector and understand the operation as the

multiplication of those two vectors modulo an irreducible polynomial.

Let’s first turn to the idea of an irreducible polynomial. An irreducible polynomial is one that cannot be factored (just as a prime number cannot be factored into components other than 1 and the prime number itself). For our purposes, we are interested in polynomials that are irreducible with respect to the set of all integers. (Note that you may be able to factor certain polynomials by, for example, the real or complex numbers, even if you cannot factor them using integers.)

For instance, consider the polynomial x^2 - 3x + 2. This can be rewritten as (x – 1)(x – 2). Hence, this

is not irreducible. Now consider the polynomial x^2 + 1. Using only integers,

there is no way to further factor this expression. Hence, this is an

irreducible polynomial with respect to the integers.

Next, let’s turn to the concept of vector multiplication. We will not explore this topic in depth, but you just need to understand a basic rule: Any vector division can take place as long as the dividend has a degree higher than or equal to that of the divisor. If the dividend has a lower degree than the divisor, then the dividend can no longer be divided by the divisor.

For instance, consider the expression x^6 + x + 1 \mod x^5 + x^2. This clearly reduces further as the degree of the dividend, 6, is higher

than the degree of the divisor, 5. Now consider the expression x^5 + x + 1 \mod x^5 + x^2.

This also reduces further, as the degree of the dividend, 5, and the

divisor, 5, are equal.

However, now consider the expression x^4 + x + 1 \mod x^5 + x^2. This does not reduce further, as the degree of the dividend, 4, is lower

than the degree of the divisor, 5.

On the basis of this information, we are now ready to find our second

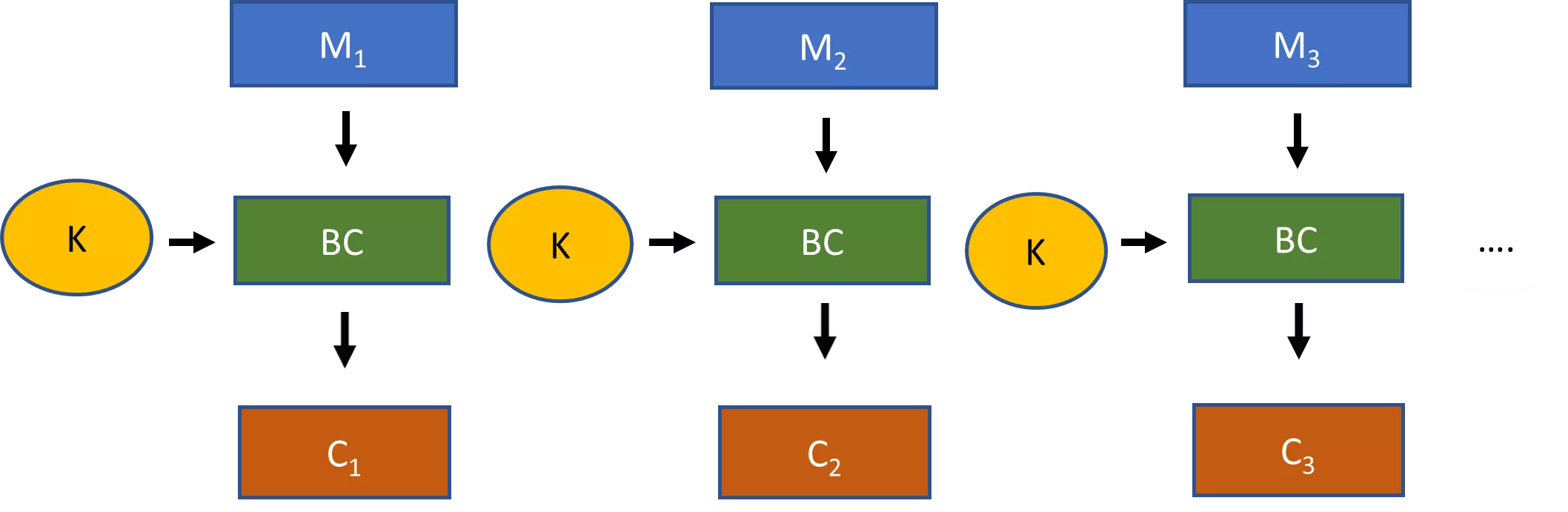

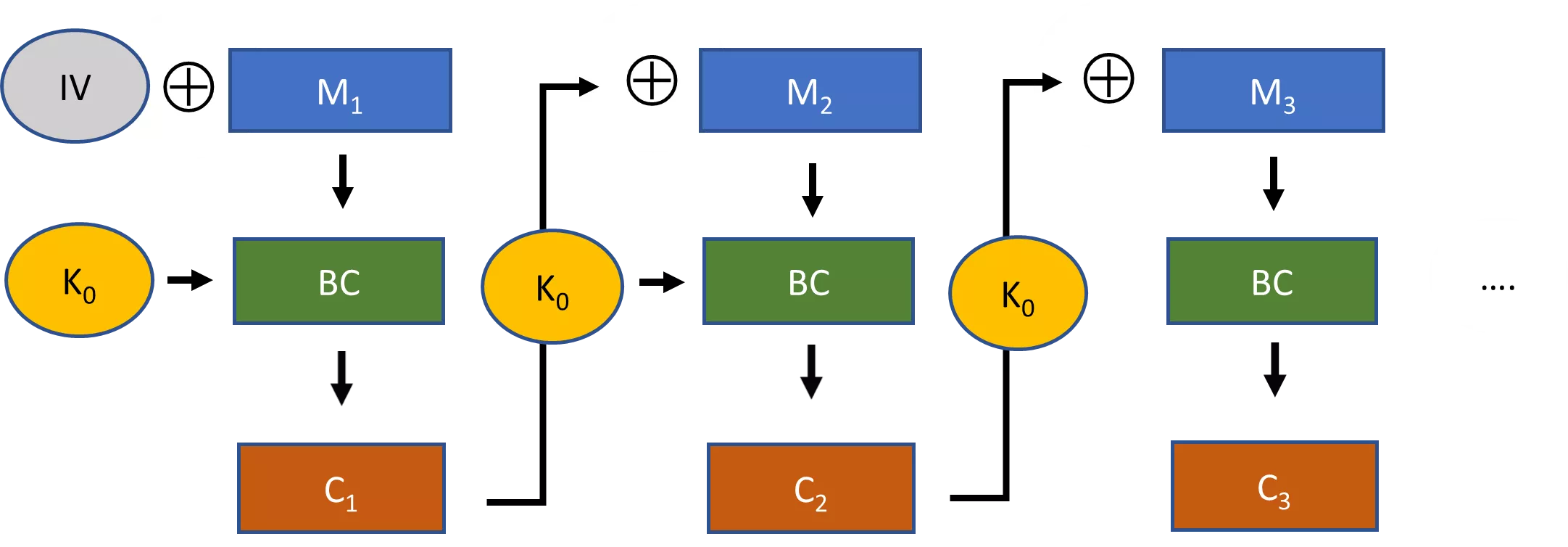

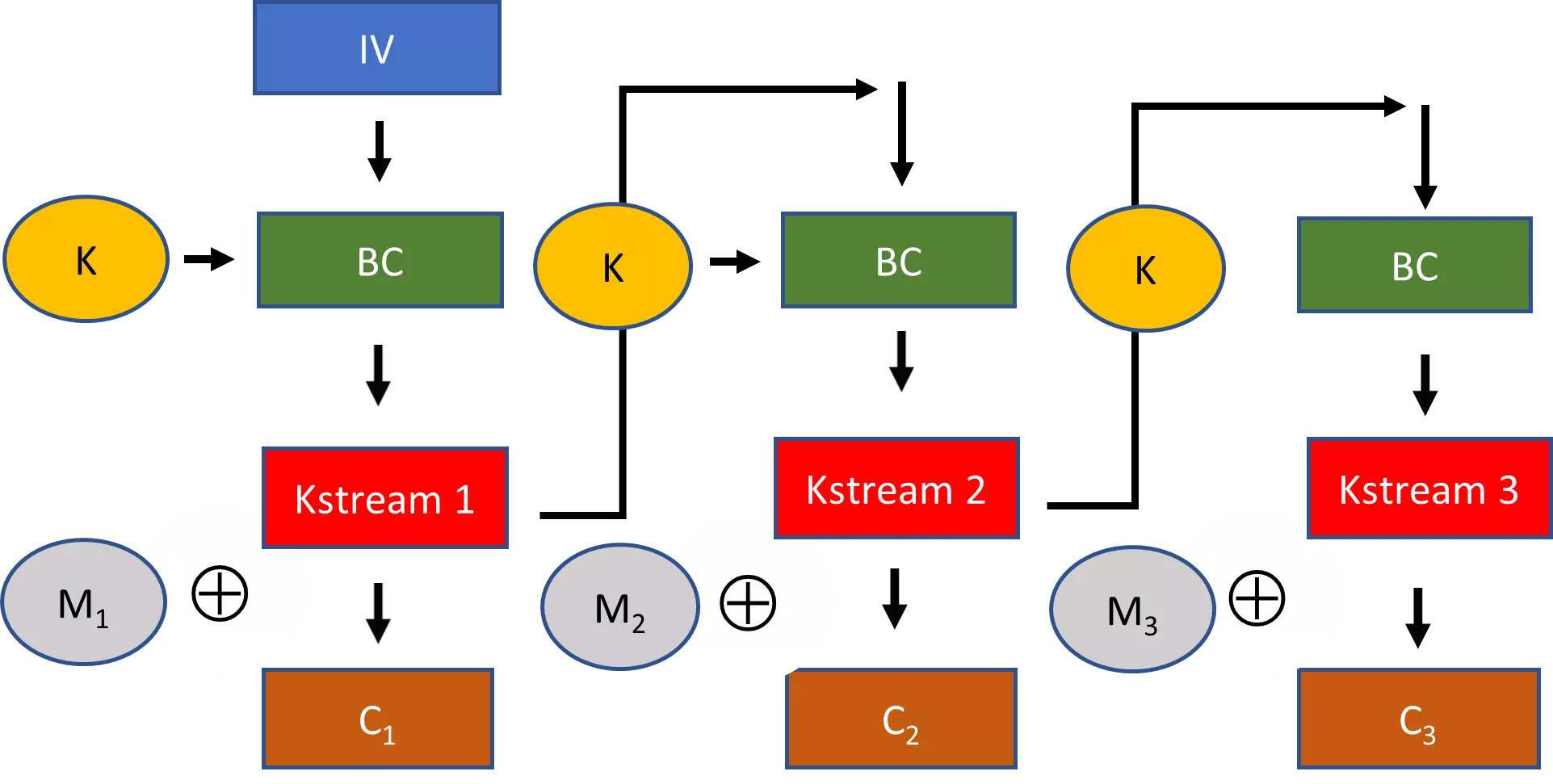

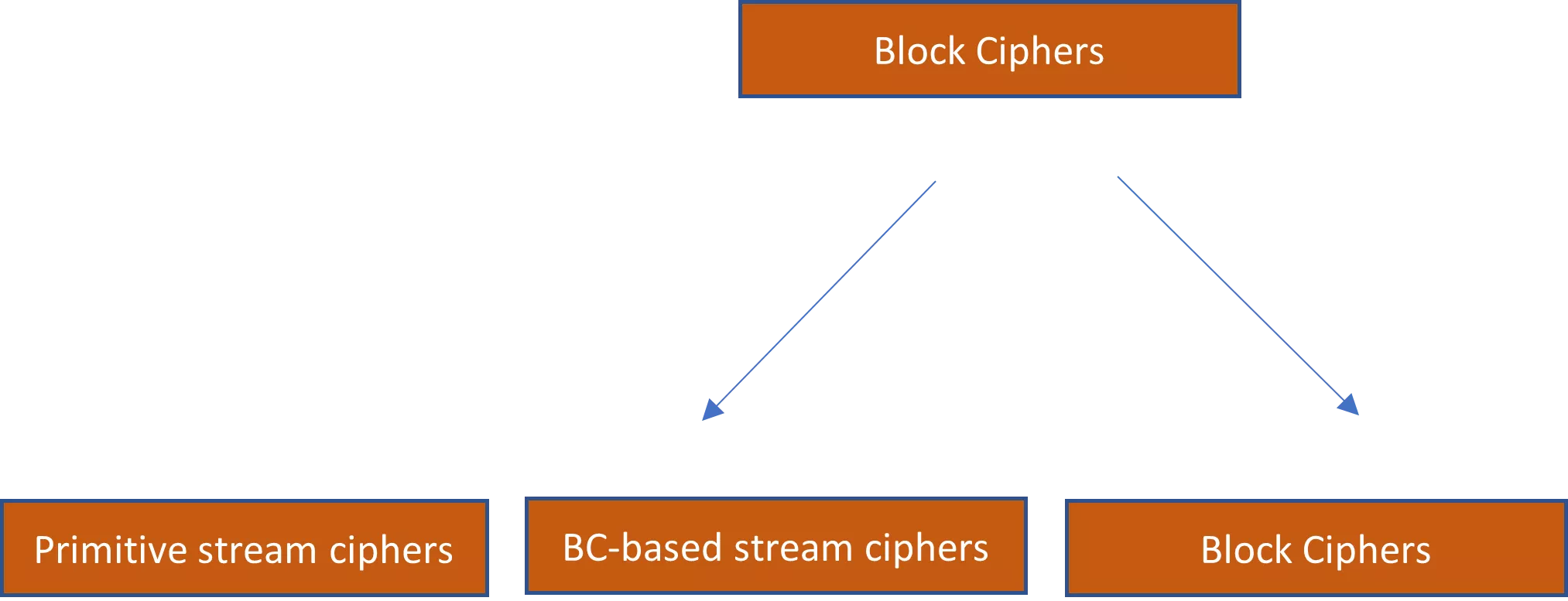

operation for the set \{0, 1, x, x + 1, x^2, x^2 + 1, x^2 + x, x^2 + x + 1\}.