name: The Inner Workings of Bitcoin Wallets goal: Dive into the cryptographic principles that power Bitcoin wallets. objectives:

- Define the theoretical notions necessary for understanding the cryptographic algorithms used in Bitcoin.

- Fully understand the construction of a deterministic and hierarchical wallet.

- Know how to identify and reduce the risks associated with managing a wallet.

- Understand the principles of hash functions, cryptographic keys, and digital signatures.

A Journey into the Heart of Bitcoin Wallets

Discover the secrets of deterministic and hierarchical Bitcoin wallets with our CYP201 course! Whether you're a regular user or an enthusiast looking to deepen your knowledge, this course offers a complete immersion into the workings of these tools that we all use daily.

Learn about the mechanisms of hash functions, digital signatures (ECDSA and Schnorr), mnemonic phrases, cryptographic keys, and the creation of receiving addresses, all while exploring advanced security strategies.

This training will not only equip you with the knowledge to understand the structure of a Bitcoin wallet but will also prepare you to dive deeper into the exciting world of cryptography.

With clear pedagogy, over 60 explanatory diagrams, and concrete examples, CYP201 will enable you to understand from A to Z how your wallet works, so you can navigate the Bitcoin universe with confidence. Take control of your UTXOs today by understanding how HD wallets function!

Introduction

Course Introduction

Welcome to the CYP201 course, where we will explore in depth the workings of HD Bitcoin wallets. This course is designed for anyone who wants to understand the technical basics of using Bitcoin, whether they are casual users, enlightened enthusiasts, or future experts.

The goal of this training is to give you the keys to master the tools you use daily. HD Bitcoin wallets, which are at the heart of your user experience, are based on sometimes complex concepts, which we will try to make accessible. Together, we will demystify them!

Before diving into the details of the construction and operation of Bitcoin wallets, we will start with a few chapters on the cryptographic primitives to know for what follows. We will start with cryptographic hash functions, fundamental for both wallets and the Bitcoin protocol itself. You will discover their main characteristics, the specific functions used in Bitcoin, and in a more technical chapter, you will learn in detail about the workings of the queen of hash functions: SHA256.

Next, we will discuss the operation of digital signature algorithms that you use every day to secure your UTXOs. Bitcoin uses two: ECDSA and the Schnorr protocol. You will learn which mathematical primitives underlie these algorithms and how they ensure the security of transactions.

Once we have a good understanding of these elements of cryptography, we will finally move on to the heart of the training: deterministic and hierarchical wallets! First, there is a section dedicated to mnemonic phrases, these sequences of 12 or 24 words that allow you to create and restore your wallets. You will discover how these words are generated from a source of entropy and how they facilitate the use of Bitcoin.

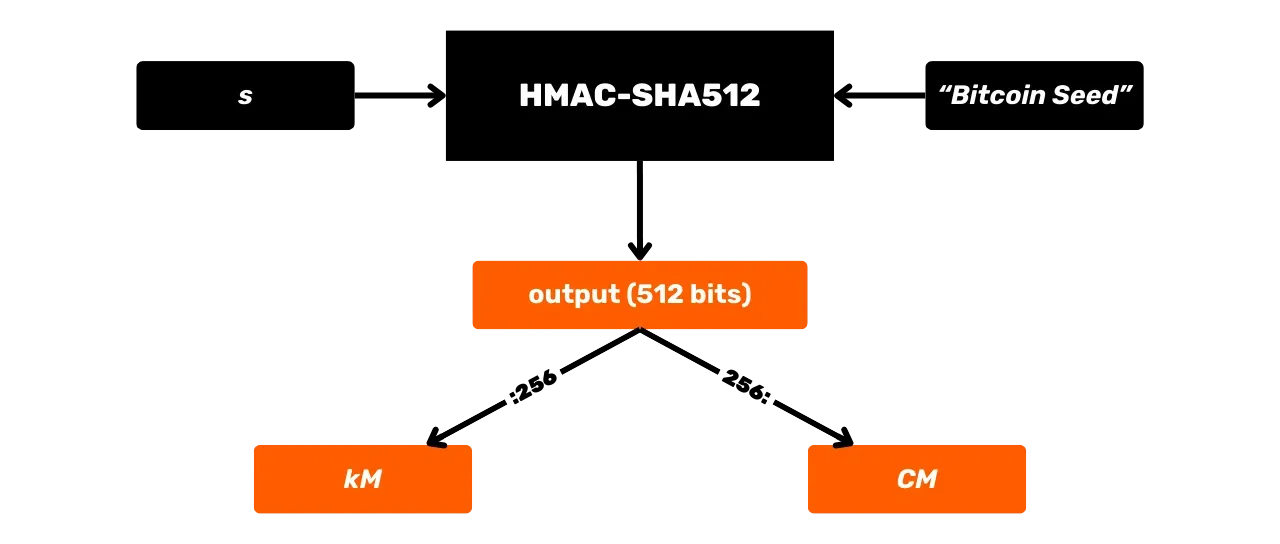

The training will continue with the study of the BIP39 passphrase, the seed (not to be confused with the mnemonic phrase), the master chain code, and the master key. We will see in detail what these elements are, their respective roles, and how they are calculated.

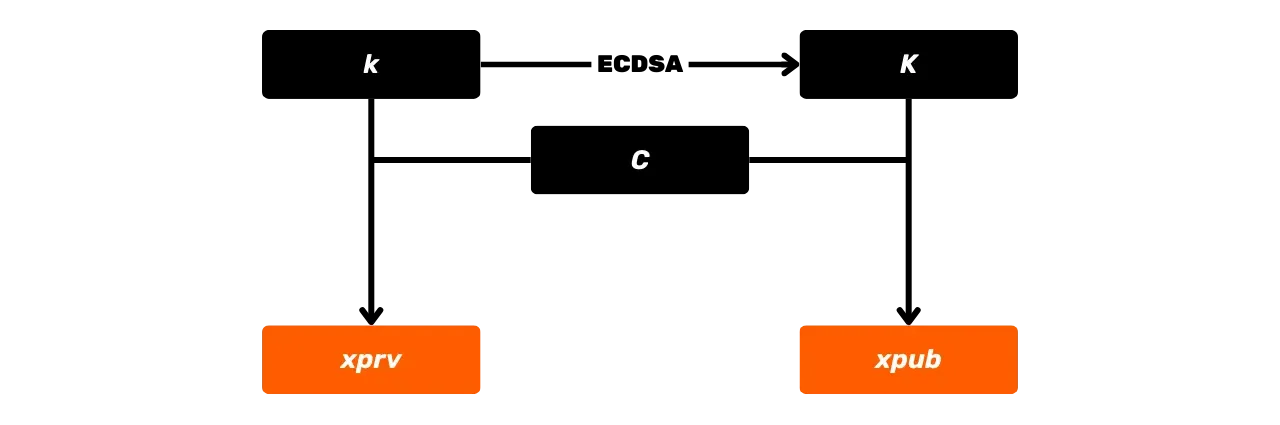

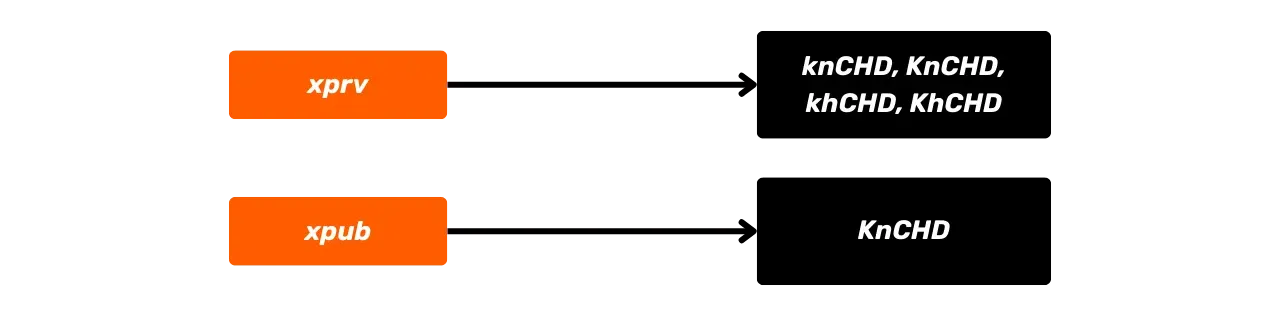

Finally, from the master key, we will discover how cryptographic key pairs are derived in a deterministic and hierarchical manner up to the receiving addresses.

This training will enable you to use your wallet software with confidence, while enhancing your skills to identify and mitigate risks. Prepare to become a true expert in Bitcoin wallets!

Hash Functions

Introduction to Hash Functions

The first type of cryptographic algorithms used in Bitcoin encompasses hash functions. They play an essential role at different levels of the protocol, but also within Bitcoin wallets. Let's discover together what a hash function is and what it's used for in Bitcoin.

Definition and Principle of Hashing

Hashing is a process that transforms information of arbitrary length into another piece of information of fixed length through a cryptographic hash function. In other words, a hash function takes an input of any size and converts it into a fixed-size fingerprint, called a "hash". The hash can also sometimes be referred to as "digest", "condensate", "condensed", or "hashed".

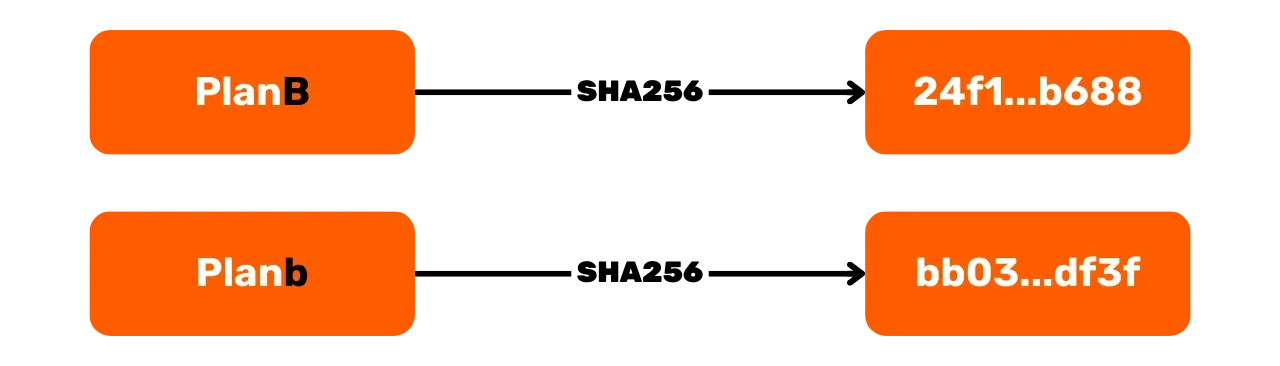

For example, the SHA256 hash function produces a hash of a fixed length of 256 bits. Thus, if we use the input "PlanB", a message of arbitrary length, the generated hash will be the following 256-bit fingerprint:

24f1b93b68026bfc24f5c8265f287b4c940fb1664b0d75053589d7a4f821b688

Characteristics of Hash Functions

These cryptographic hash functions have several essential characteristics that make them particularly useful in the context of Bitcoin and other computer systems:

- Irreversibility (or preimage resistance)

- Tamper resistance (avalanche effect)

- Collision resistance

- Second preimage resistance

1. Irreversibility (preimage resistance):

Irreversibility means that it is easy to calculate the hash from the input information, but the inverse calculation, that is, finding the input from the hash, is practically impossible. This property makes hash functions perfect for creating unique digital fingerprints without compromising the original information. This characteristic is often referred to as a one-way function.

In the given example, obtaining the hash 24f1b9… by knowing the

input "PlanB" is simple and quick. However, finding the message "PlanB" by only knowing 24f1b9… is impossible.

Therefore, it is impossible to find a preimage m for a hash h such that h = \text{HASH}(m),

where \text{HASH} is

a cryptographic hash function.

2. Tamper resistance (avalanche effect)

The second characteristic is tamper resistance, also known as the avalanche effect. This characteristic is observed in a hash function if a small change in the input message results in a radical change in the output hash.

If we go back to our example with the input "PlanB" and the SHA256 function, we have seen that the generated hash is as follows:

24f1b93b68026bfc24f5c8265f287b4c940fb1664b0d75053589d7a4f821b688

If we make a very slight change to the input by using "Planb" this time, then simply changing from an uppercase "B" to a lowercase "b" completely alters the SHA256 output hash:

bb038b4503ac5d90e1205788b00f8f314583c5e22f72bec84b8735ba5a36df3f

This property ensures that even a minor alteration of the original message is immediately detectable, as it does not just change a small part of the hash, but the entire hash. This can be of interest in various fields to verify the integrity of messages, software, or even Bitcoin transactions.

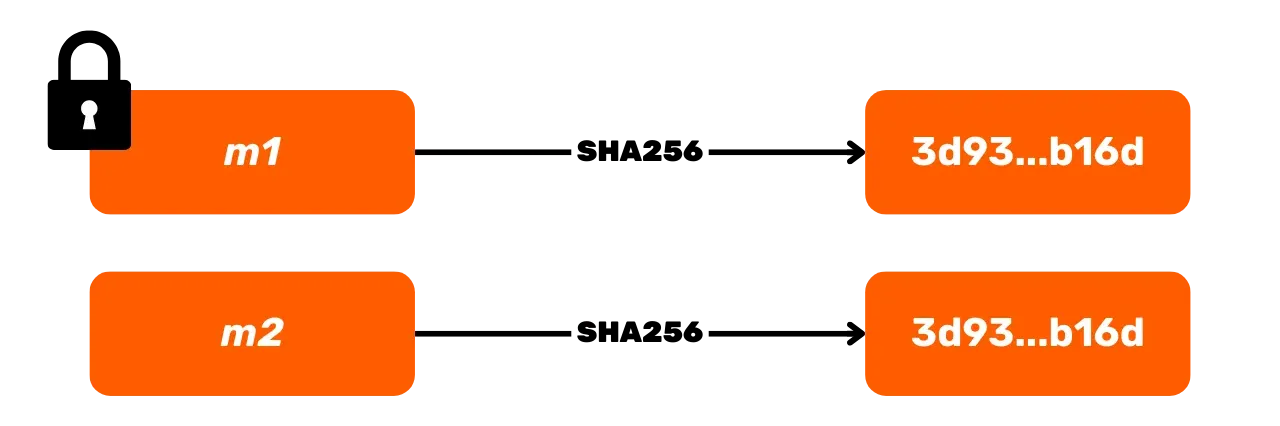

3. Collision Resistance

The third characteristic is collision resistance. A hash function is

collision-resistant if it is computationally impossible to find 2 different

messages that produce the same hash output from the function. Formally, it

is difficult to find two distinct messages m_1 and m_2 such that:

\text{HASH}(m_1) = \text{HASH}(m_2)

In reality, it is mathematically inevitable that collisions exist for hash

functions, because the size of the inputs can be larger than the size of the

outputs. This is known as the Dirichlet drawer principle: if n objects are distributed into m drawers, with m < n,

then at least one drawer will necessarily contain two or more objects. For a

hash function, this principle applies because the number of possible

messages is (almost) infinite, while the number of possible hashes is finite

(2^{256} in the case

of SHA256).

Thus, this characteristic does not mean that there are no collisions for

hash functions, but rather that a good hash function makes the probability

of finding a collision negligible. This characteristic, for example, is no

longer verified on the SHA-0 and SHA-1 algorithms, predecessors of SHA-2,

for which collisions have been found. These functions are therefore now

advised against and often considered obsolete. For a hash function of n bits, the collision resistance is of the order of 2^{\frac{n}{2}}, in accordance with the birthday attack. For example, for SHA256 (n = 256), the complexity of finding a collision is of the order of 2^{128} attempts. In practical terms, this means that if one passes 2^{128} different messages

through the function, one is likely to find a collision.

4. Resistance to Second Preimage

Resistance to second preimage is another important characteristic of hash

functions. It states that given a message m_1 and its hash h, it is

computationally infeasible to find another message m_2 \neq m_1 such that:

\text{HASH}(m_1) = \text{HASH}(m_2)Therefore, resistance to second preimage is somewhat similar to collision

resistance, except here, the attack is more difficult because the attacker

cannot freely choose m_1.

Applications of Hash Functions in Bitcoin

The most used hash function in Bitcoin is SHA256 ("Secure Hash Algorithm 256 bits"). Designed in the early 2000s by the NSA and standardized by the NIST, it produces a 256-bit hash output.

This function is used in many aspects of Bitcoin. At the protocol level, it is involved in the Proof-of-Work mechanism, where it is applied in double hashing to search for a partial collision between the header of a candidate block, created by a miner, and the difficulty target. If this partial collision is found, the candidate block becomes valid and can be added to the blockchain.

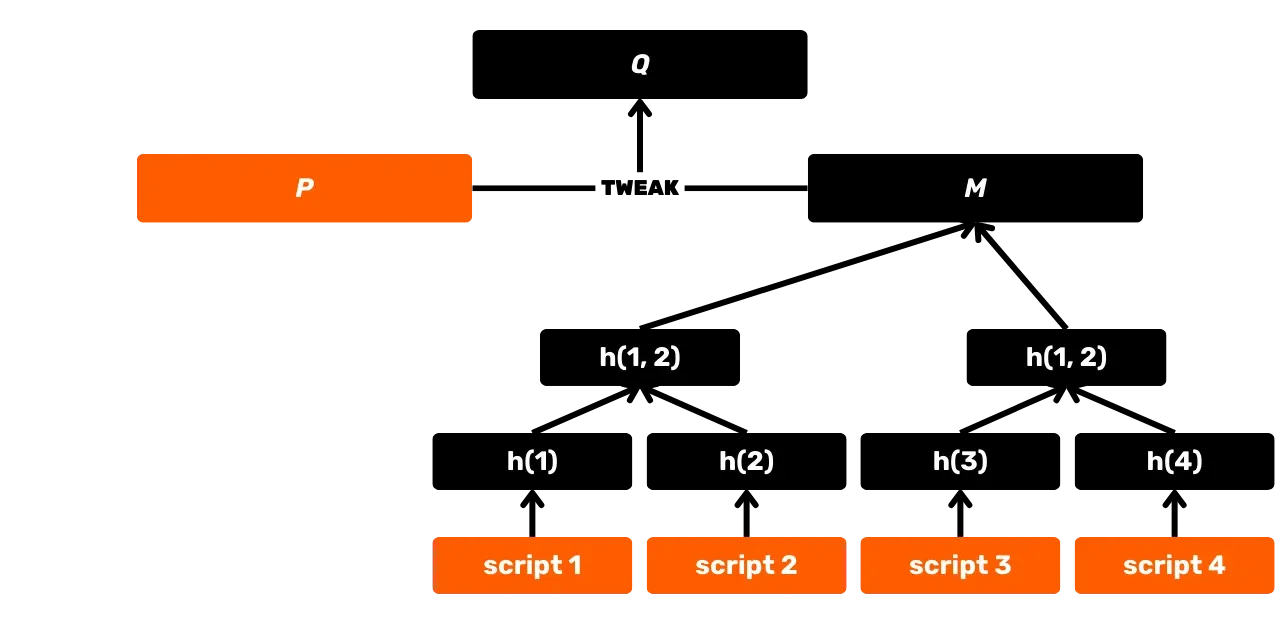

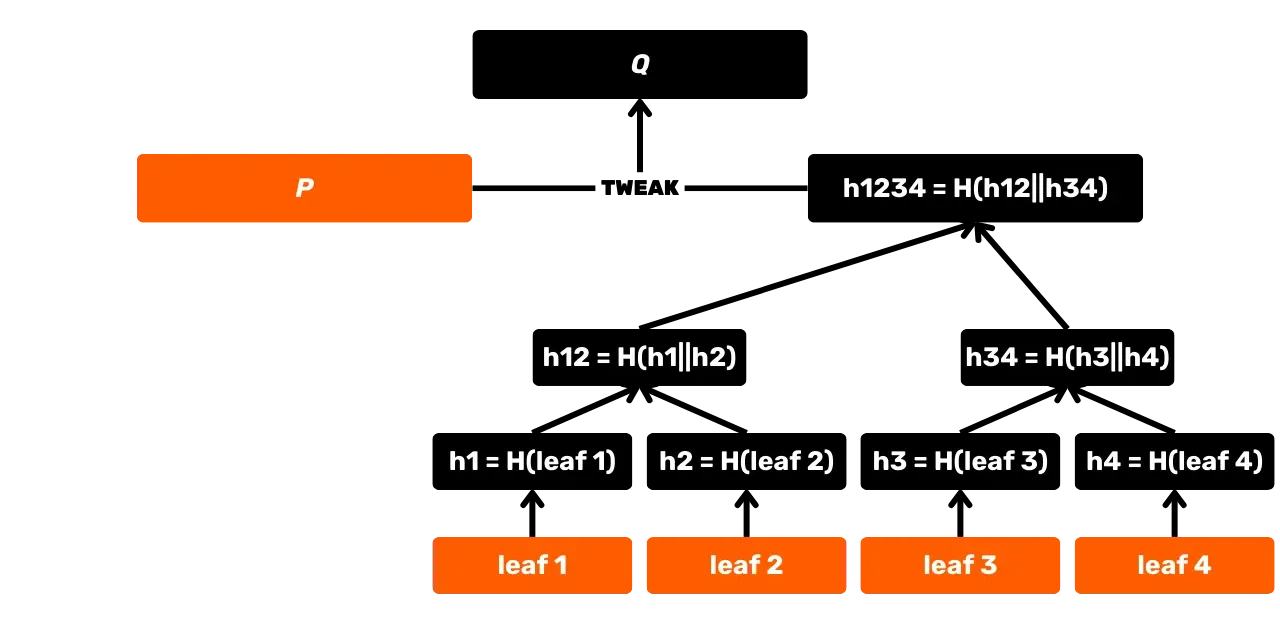

SHA256 is also used in the construction of a Merkle tree, which is notably the accumulator used for recording transactions in blocks. This structure is also found in the Utreexo protocol, which allows for reducing the size of the UTXO Set. Additionally, with the introduction of Taproot in 2021, SHA256 is exploited in MAST (Merkelised Alternative Script Tree), which allows revealing only the spending conditions actually used in a script, without disclosing the other possible options. It is also used in the calculation of transaction identifiers, in the transmission of packets over the P2P network, in electronic signatures... Finally, and this is of particular interest in this training, SHA256 is used at the application level for the construction of Bitcoin wallets and the derivation of addresses.

Most of the time, when you come across the use of SHA256 in Bitcoin, it will actually be a double hash SHA256, noted "HASH256", which simply consists of applying SHA256 twice successively:

\text{HASH256}(m) = \text{SHA256}(\text{SHA256}(m))This practice of double hashing adds an extra layer of security against certain potential attacks, even though a single SHA256 is today considered cryptographically secure.

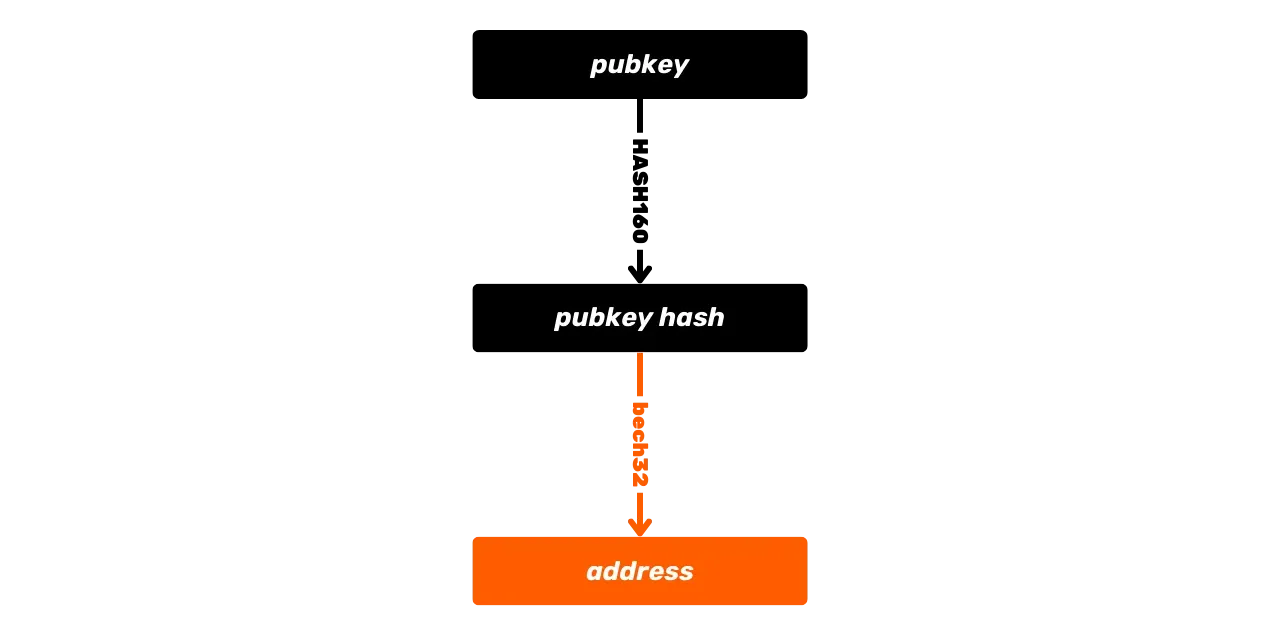

Another hashing function available in the Script language and used for deriving receiving addresses is the RIPEMD160 function. This function produces a 160-bit hash (thus shorter than SHA256). It is generally combined with SHA256 to form the HASH160 function:

\text{HASH160}(m) = \text{RIPEMD160}(\text{SHA256}(m))This combination is used to generate shorter hashes, notably in the creation of certain Bitcoin addresses which represent hashes of keys or script hashes, as well as to produce key fingerprints.

Finally, at the application level only, the SHA512 function is sometimes also used, which indirectly plays a role in key derivation for wallets. This function is very similar to SHA256 in its operation; both belong to the same SHA2 family, but SHA512 produces, as its name indicates, a 512-bit hash, compared to 256 bits for SHA256. We will detail its use in the following chapters.

You now know the essential basics about hashing functions for what follows. In the next chapter, I propose to discover in more detail the workings of the function that is at the heart of Bitcoin: SHA256. We will dissect it to understand how it achieves the characteristics we have described here. This next chapter is quite long and technical, but it is not essential to follow the rest of the training. So, if you have difficulty understanding it, do not worry and move directly to the following chapter, which will be much more accessible.

The Inner Workings of SHA256

We have previously seen that hashing functions possess important characteristics that justify their use in Bitcoin. Let's now examine the internal mechanisms of these hashing functions that give them these properties, and to do this, I propose to dissect the operation of SHA256.

The SHA256 and SHA512 functions belong to the same SHA2 family. Their mechanism is based on a specific construction called Merkle-Damgård construction. RIPEMD160 also uses this same type of construction.

As a reminder, we have a message of arbitrary size as input to SHA256, and we will pass it through the function to obtain a 256-bit hash as output.

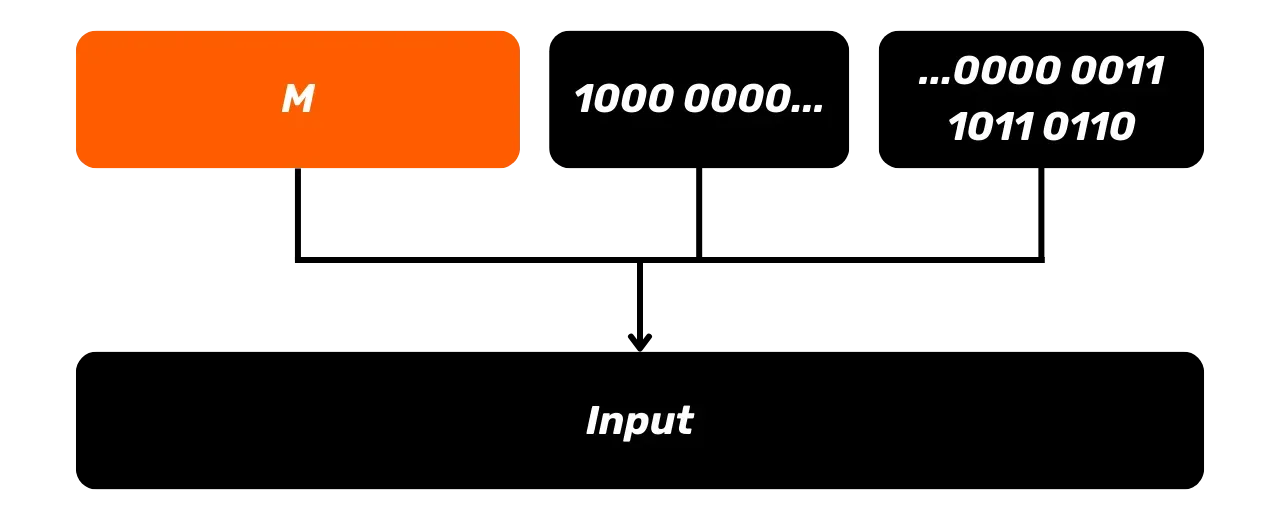

Pre-processing of the input

To begin, we need to prepare our input message m so that it has a standard length that is a multiple of 512 bits. This step

is crucial for the proper functioning of the algorithm subsequently. To do

this, we start with the padding bits step. We first add a separator bit 1 to the message, followed by a certain number of 0 bits. The

number of 0 bits added is calculated so that the total length

of the message after this addition is congruent to 448 modulo 512. Thus, the

length L of the message with the

padding bits is equal to:

L \equiv 448 \mod 512\text{mod}, for

modulo, is a mathematical operation that, between two integers, returns the

remainder of the Euclidean division of the first by the second. For example: 16 \mod 5 = 1. It is an

operation widely used in cryptography.

Here, the padding step ensures that, after adding the 64 bits in the next

step, the total length of the equalized message will be a multiple of 512

bits. If the initial message has a length of M bits, the number (N) of 0 bits to be added is thus:

N = (448 - (M + 1) \mod 512) \mod 512For example, if the initial message is 950 bits, the calculation would be as follows:

\begin{align*}

M & = 950 \\

M + 1 & = 951 \\

(M + 1) \mod 512 & = 951 \mod 512 \\

& = 951 - 512 \cdot \left\lfloor \frac{951}{512} \right\rfloor \\

& = 951 - 512 \cdot 1 \\

& = 951 - 512 \\

& = 439 \\

\\

448 - (M + 1) \mod 512 & = 448 - 439 \\

& = 9 \\

\\

N & = (448 - (M + 1) \mod 512) \mod 512 \\

N & = 9 \mod 512 \\

& = 9

\end{align*}Thus, we would have 9 0s in addition to the separator 1. Our padding bits to be added directly after our message M would thus be:

1000 0000 00

After adding the padding bits to our message M, we also add a 64-bit representation of the original length of the message M, expressed in binary. This

allows the hash function to be sensitive to the order of bits and the length

of the message.

If we go back to our example with an initial message of 950 bits, we convert

the decimal number 950 into binary, which gives us 1110 1101 10. We complete this number with zeros at the base to

make a total of 64 bits. In our example, this gives:

0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0011 1011 0110

This padding size is added following the bit padding. Therefore, the message after our preprocessing consists of three parts:

- The original message

M; - A bit

1followed by several bits0to form the bit padding; - A 64-bit representation of the length of

Mto form the padding with the size.

Initialization of Variables

SHA256 uses eight initial state variables, denoted A to H, each of 32 bits. These

variables are initialized with specific constants, which are the fractional

parts of the square roots of the first eight prime numbers. We will use

these values subsequently during the hashing process:

A = 0x6a09e667B = 0xbb67ae85C = 0x3c6ef372D = 0xa54ff53aE = 0x510e527fF = 0x9b05688cG = 0x1f83d9abH = 0x5be0cd19

SHA256 also uses 64 other constants, denoted K_0 to K_{63}, which

are the fractional parts of the cube roots of the first 64 prime numbers:

K[0 \ldots 63] = \begin{pmatrix}

0x428a2f98, & 0x71374491, & 0xb5c0fbcf, & 0xe9b5dba5, \\

0x3956c25b, & 0x59f111f1, & 0x923f82a4, & 0xab1c5ed5, \\

0xd807aa98, & 0x12835b01, & 0x243185be, & 0x550c7dc3, \\

0x72be5d74, & 0x80deb1fe, & 0x9bdc06a7, & 0xc19bf174, \\

0xe49b69c1, & 0xefbe4786, & 0x0fc19dc6, & 0x240ca1cc, \\

0x2de92c6f, & 0x4a7484aa, & 0x5cb0a9dc, & 0x76f988da, \\

0x983e5152, & 0xa831c66d, & 0xb00327c8, & 0xbf597fc7, \\

0xc6e00bf3, & 0xd5a79147, & 0x06ca6351, & 0x14292967, \\

0x27b70a85, & 0x2e1b2138, & 0x4d2c6dfc, & 0x53380d13, \\

0x650a7354, & 0x766a0abb, & 0x81c2c92e, & 0x92722c85, \\

0xa2bfe8a1, & 0xa81a664b, & 0xc24b8b70, & 0xc76c51a3, \\

0xd192e819, & 0xd6990624, & 0xf40e3585, & 0x106aa070, \\

0x19a4c116, & 0x1e376c08, & 0x2748774c, & 0x34b0bcb5, \\

0x391c0cb3, & 0x4ed8aa4a, & 0x5b9cca4f, & 0x682e6ff3, \\

0x748f82ee, & 0x78a5636f, & 0x84c87814, & 0x8cc70208, \\

0x90befffa, & 0xa4506ceb, & 0xbef9a3f7, & 0xc67178f2

\end{pmatrix}Division of the Input

Now that we have an equalized input, we will now move on to the main processing phase of the SHA256 algorithm: the compression function. This step is very important, as it is primarily what gives the hash function its cryptographic properties that we studied in the previous chapter.

First, we start by dividing our equalized message (result of the

preprocessing steps) into several blocks P of 512 bits each. If our equalized message has a total size of n \times 512 bits, we will therefore have n blocks, each of 512 bits. Each 512-bit block will be processed individually

by the compression function, which consists of 64 rounds of successive

operations. Let's name these blocks P_1, P_2, P_3...

Logical Operations

Before exploring the compression function in detail, it is important to understand the basic logical operations used in it. These operations, based on Boolean algebra, operate at the bit level. The basic logical operations used are:

- Conjunction (AND): denoted

\land, corresponds to a logical "AND". - Disjunction (OR): denoted

\lor, corresponds to a logical "OR". - Negation (NOT): denoted

\lnot, corresponds to a logical "NOT".

From these basic operations, we can define more complex operations, such as

the "Exclusive OR" (XOR) denoted \oplus, which is widely used in cryptography. Every logical operation can be

represented by a truth table, which indicates the result for all possible

combinations of binary input values (two operands p and q). For XOR (\oplus):

p | q | p \oplus q |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

For AND (\land):

p | q | p \land q |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

For NOT (\lnot p):

p | \lnot p |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 |

Let's take an example to understand the operation of XOR at the bit level. If we have two binary numbers on 6 bits:

a = 101100b = 001000

Then:

a \oplus b = 101100 \oplus 001000 = 100100

By applying XOR bit by bit:

| Bit Position | a | b | a \oplus b |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The result is therefore 100100.

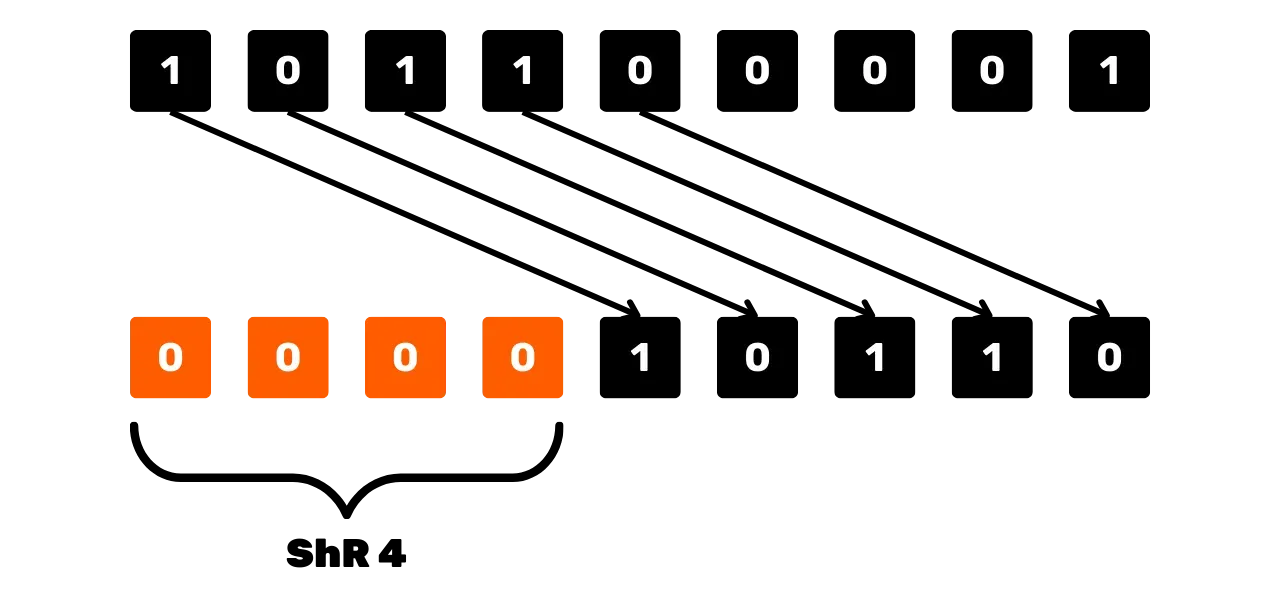

In addition to logical operations, the compression function uses bit-shifting operations, which will play an essential role in the diffusion of bits in the algorithm.

First, there is the logical right shift operation, denoted ShR_n(x), which shifts all the bits of x to the right by n positions, filling

the vacant bits on the left with zeros.

For example, for x = 101100001 (on 9 bits) and n = 4:

ShR_4(101100001) = 000010110

Schematically, the right shift operation could be seen like this:

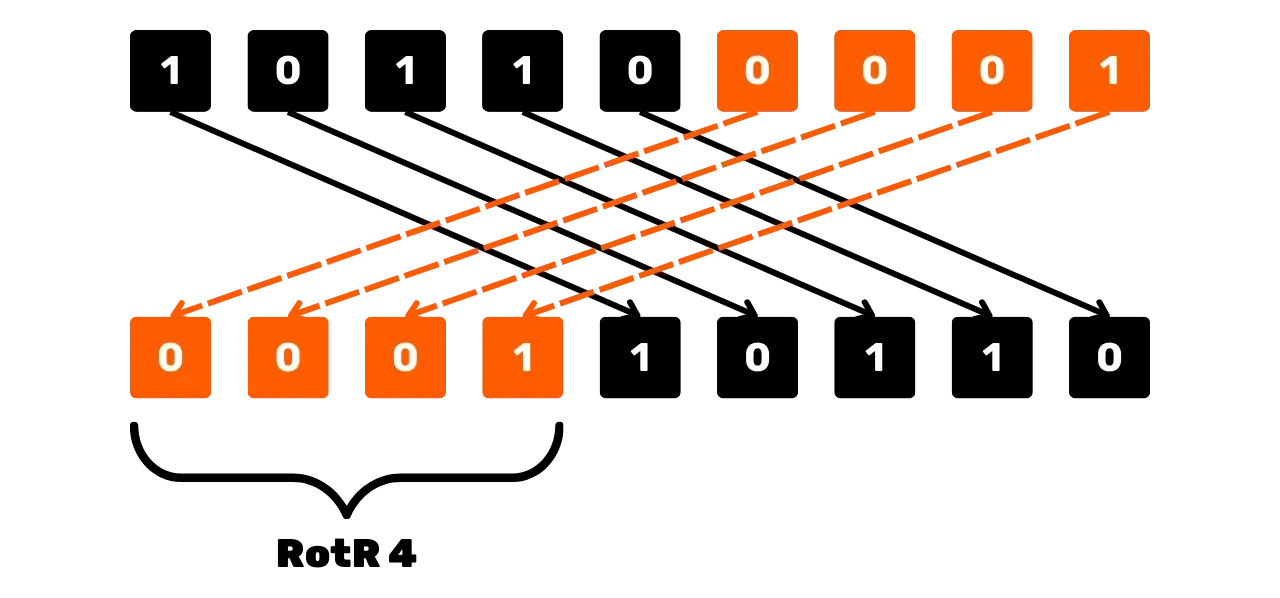

Another operation used in SHA256 for bit manipulation is the right circular

rotation, denoted RotR_n(x),

which shifts the bits of x to

the right by n positions,

reinserting the shifted bits at the beginning of the string. For example,

for x = 101100001 (over 9

bits) and n = 4:

RotR_4(101100001) = 000110110

Schematically, the right circular shift operation could be seen like this:

Compression Function

Now that we have understood the basic operations, let's examine the SHA256 compression function in detail.

In the previous step, we divided our input into several 512-bit pieces P. For each 512-bit block P,

we have:

- The message words

W_i: forifrom 0 to 63. - The constants

K_i: forifrom 0 to 63, defined in the previous step. - The state variables

A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H: initialized with the values from the previous step.

The first 16 words, W_0 to W_{15}, are

directly extracted from the processed 512-bit block P. Each word W_i consists of 32 consecutive bits from the block. So, for example, we take our

first piece of input P_1, and

we further divide it into smaller 32-bit pieces that we call words.

The next 48 words (W_{16} to W_{63}) are

generated using the following formula:

W_i = W_{i-16} + \sigma_0(W_{i-15}) + W_{i-7} + \sigma_1(W_{i-2}) \mod 2^{32}With:

\sigma_0(x) = RotR_7(x) \oplus RotR_{18}(x) \oplus ShR_3(x)\sigma_1(x) = RotR_{17}(x) \oplus RotR_{19}(x) \oplus ShR_{10}(x)

In this case, x equals W_{i-15} for \sigma_0(x) and W_{i-2} for \sigma_1(x).

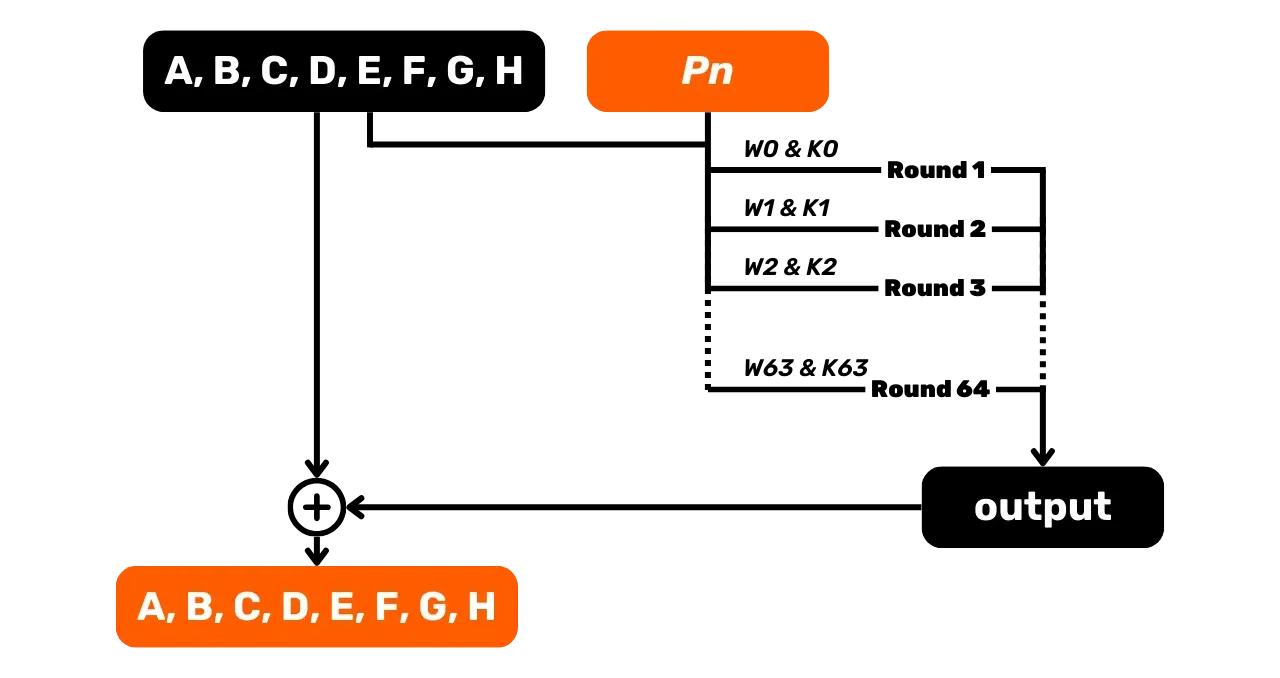

Once we have determined all the words W_i for our 512-bit piece, we can move on to the compression function, which consists

of performing 64 rounds.

For each round

For each round i from 0 to

63, we have three different types of inputs. First, the W_i that we have just determined, partly consisting of our message piece P_n. Next, the 64 constants K_i. Finally, we use the

state variables A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H, which will evolve

throughout the hashing process and be modified with each compression

function. However, for the first piece P_1, we use the initial

constants given previously.

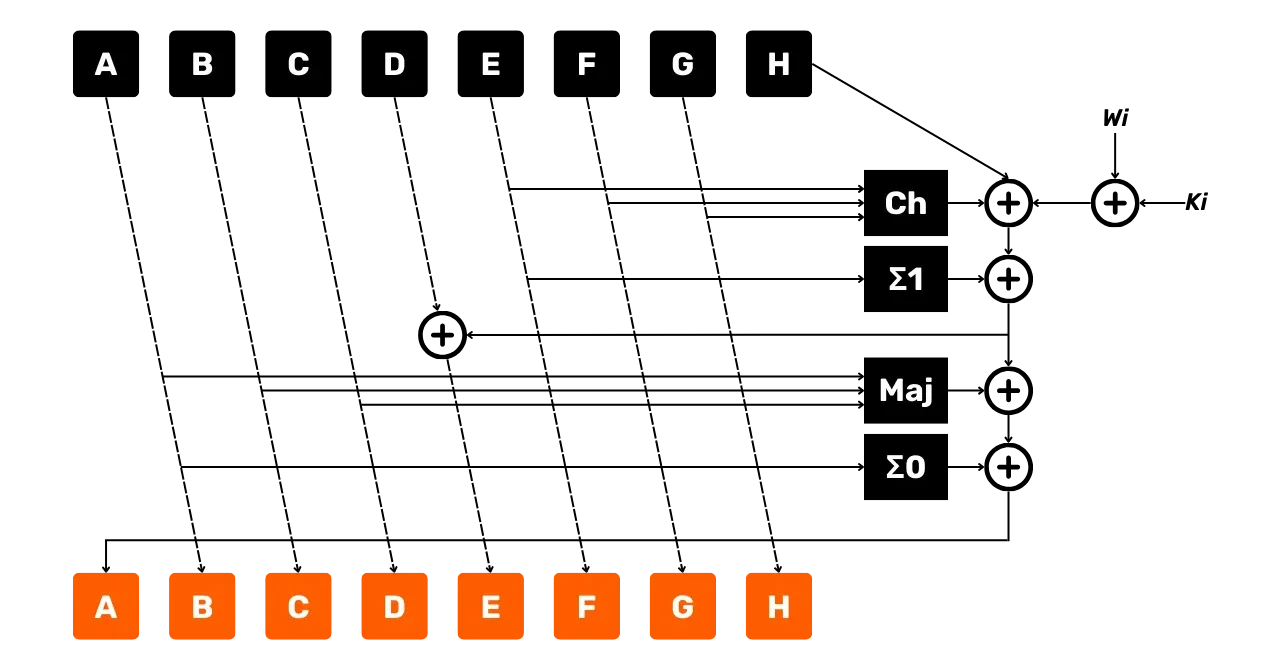

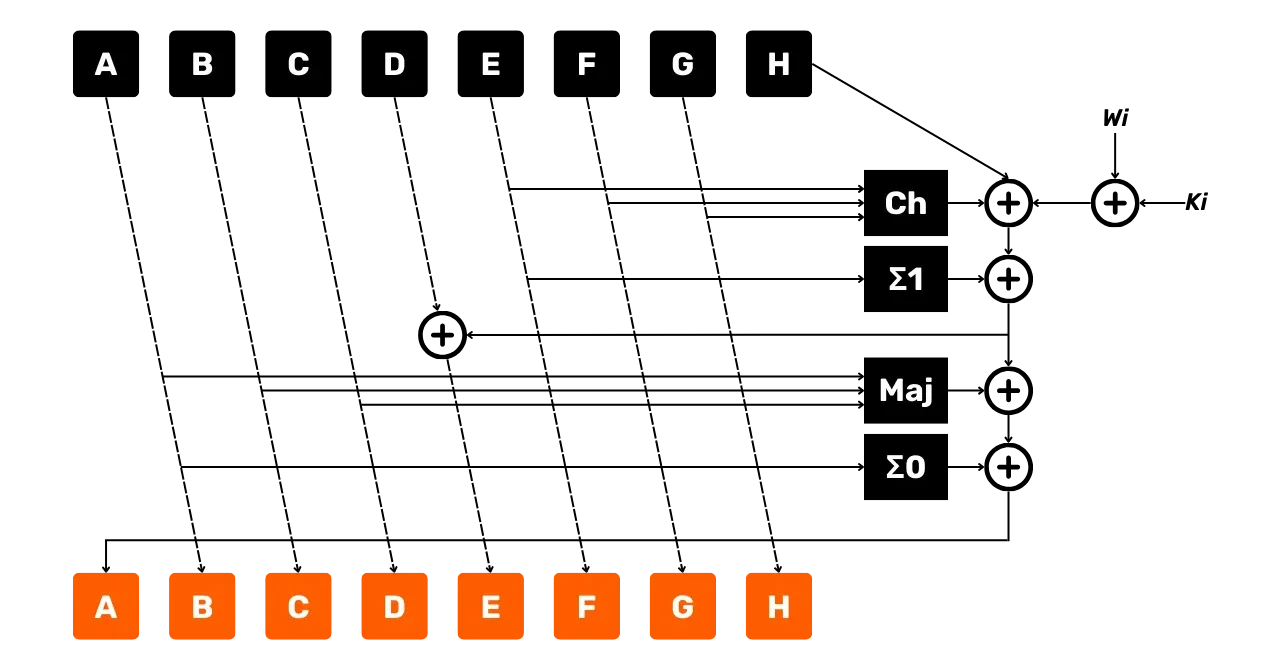

We then perform the following operations on our inputs:

- Function

\Sigma_0:

\Sigma_0(A) = RotR_2(A) \oplus RotR_{13}(A) \oplus RotR_{22}(A)- Function

\Sigma_1:

\Sigma_1(E) = RotR_6(E) \oplus RotR_{11}(E) \oplus RotR_{25}(E)- Function

Ch("Choose"):

Ch(E, F, G) = (E \land F) \oplus (\lnot E \land G)- Function

Maj("Majority"):

Maj(A, B, C) = (A \land B) \oplus (A \land C) \oplus (B \land C)We then calculate 2 temporary variables:

temp1:

temp1 = H + \Sigma_1(E) + Ch(E, F, G) + K_i + W_i \mod 2^{32}temp2:

temp2 = \Sigma_0(A) + Maj(A, B, C) \mod 2^{32}Next, we update the state variables as follows:

\begin{cases}

H = G \\

G = F \\

F = E \\

E = D + temp1 \mod 2^{32} \\

D = C \\

C = B \\

B = A \\

A = temp1 + temp2 \mod 2^{32}

\end{cases}The following diagram represents a round of the SHA256 compression function as we have just described:

- The arrows indicate the flow of data;

- The boxes represent the operations performed;

- The

+surrounded represent the addition modulo2^{32}.

We can already observe that this round outputs new state variables A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H. These new variables will

serve as input for the next round, which will in turn produce new variables A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H, to be used for the

following round. This process continues up to the 64th round. After the 64

rounds, we update the initial values of the state variables by adding them

to the final values at the end of round 64:

\begin{cases}

A = A_{\text{initial}} + A \mod 2^{32} \\

B = B_{\text{initial}} + B \mod 2^{32} \\

C = C_{\text{initial}} + C \mod 2^{32} \\

D = D_{\text{initial}} + D \mod 2^{32} \\

E = E_{\text{initial}} + E \mod 2^{32} \\

F = F_{\text{initial}} + F \mod 2^{32} \\

G = G_{\text{initial}} + G \mod 2^{32} \\

H = H_{\text{initial}} + H \mod 2^{32}

\end{cases}These new values of A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H will serve as the initial values for the next block, P_2. For this block P_2, we replicate the same

compression process with 64 rounds, then we update the variables for block P_3, and so on until the last

block of our equalized input.

After processing all the message blocks, we concatenate the final values of

the variables A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H to form the final 256-bit hash

of our hashing function:

\text{Hash} = A \Vert B \Vert C \Vert D \Vert E \Vert F \Vert G \Vert H

Each variable is a 32-bit integer, so their concatenation always yields a 256-bit result, regardless of the size of our message input to the hashing function.

Justification of Cryptographic Properties

But then, how is this function irreversible, collision-resistant, and tamper-resistant?

For tamper resistance, it's quite simple to understand. There are so many

calculations performed in cascade, which depend both on the input and the

constants, that the slightest modification of the initial message completely

changes the path taken, and thus completely changes the output hash. This is

what is called the avalanche effect. This property is partly ensured by the

mixing of the intermediate states with the initial states for each piece.

Next, when discussing a cryptographic hash function, the term

"irreversibility" is not generally used. Instead, we talk about "preimage

resistance," which specifies that for any given y, it is difficult to find an x such that h(x) = y. This

preimage resistance is guaranteed by the algebraic complexity and the strong

non-linearity of the operations performed in the compression function, as

well as by the loss of certain information in the process. For example, for

a given result of an addition modulo, there are several possible operands:

3+2 \mod 10 = 5 \\

7+8 \mod 10 = 5 \\

5+10 \mod 10 = 5

In this example, knowing only the modulo used (10) and the result (5), one cannot determine with certainty which are the correct operands used in the addition. It is said that there are multiple congruences modulo 10.

For the XOR operation, we are faced with the same problem. Remember the

truth table for this operation: any 1-bit output can be determined by two

different input configurations that have exactly the same probability of

being the correct values. Therefore, one cannot determine with certainty the

operands of an XOR by knowing only its result. If we increase the size of

the XOR operands, the number of possible inputs knowing only the result

increases exponentially. Moreover, XOR is often used alongside other

bit-level operations, such as the \text{RotR} operation, which add even more possible interpretations to the result.

The compression function also uses the \text{ShR} operation. This operation removes a part of the basic information, which is

then impossible to retrieve later. Once again, there is no algebraic means to

reverse this operation. All these one-way and information-loss operations are

used very frequently in compression functions. The number of possible inputs

for a given output is thus almost infinite, and each attempt at reverse calculation

would lead to equations with a very high number of unknowns, which would increase

exponentially at each step.

Finally, for the characteristic of collision resistance, several parameters come into play. The pre-processing of the original message plays an essential role. Without this pre-processing, it might be easier to find collisions on the function. Although, theoretically, collisions exist (due to the pigeonhole principle), the structure of the hash function, combined with the aforementioned properties, makes the probability of finding a collision extremely low. For a hash function to be collision-resistant, it is essential that:

- The output is unpredictable: Any predictability can be exploited to find collisions faster than with a brute force attack. The function ensures that each bit of the output depends in a non-trivial way on the input. In other words, the function is designed so that each bit of the final result has an independent probability of being 0 or 1, even if this independence is not absolute in practice.

- The distribution of hashes is pseudo-random: This ensures that the hashes are uniformly distributed.

- The size of the hash is substantial: the larger the possible space for results, the more difficult it is to find a collision.

Cryptographers design these functions by evaluating the best possible attacks to find collisions, then adjusting the parameters to render these attacks ineffective.

Merkle-Damgård Construction

The structure of SHA256 is based on the Merkle-Damgård construction, which allows transforming a compression function into a hash function that can process messages of arbitrary length. This is precisely what we have seen in this chapter.

However, some old hash functions like SHA1 or MD5, which use this specific

construction, are vulnerable to length extension attacks. This is a

technique that allows an attacker who knows the hash of a message M and the length of M (without

knowing the message itself) to calculate the hash of a message M' formed by concatenating M with

additional content.

SHA256, even though it uses the same type of construction, is theoretically resistant to this type of attack, unlike SHA1 and MD5. This might explain the mystery of the double hashing implemented throughout Bitcoin by Satoshi Nakamoto. To avoid this type of attack, Satoshi might have preferred to use a double SHA256:

\text{HASH256}(m) = \text{SHA256}(\text{SHA256}(m))

This enhances security against potential attacks related to the Merkle-Damgård construction, but it does not increase the hashing process's security in terms of collision resistance. Moreover, even if SHA256 had been vulnerable to this type of attack, it would not have had a serious impact, as all use cases of hash functions in Bitcoin involve public data. However, the length extension attack might only be useful for an attacker if the hashed data are private and the user has used the hash function as an authentication mechanism for these data, similar to a MAC. Thus, the implementation of double hashing remains a mystery in the design of Bitcoin. Now that we have looked in detail at the workings of hash functions, particularly SHA256, which is used extensively in Bitcoin, we will focus more specifically on the cryptographic derivation algorithms used at the application level, especially for deriving the keys for your wallet.

The algorithms used for derivation

In Bitcoin at the application level, in addition to hash functions, cryptographic derivation algorithms are used to generate secure data from initial inputs. Although these algorithms rely on hash functions, they serve different purposes, especially in terms of authentication and key generation. These algorithms retain some of the characteristics of hash functions, such as irreversibility, tamper resistance, and collision resistance.

In Bitcoin wallets, mainly 2 derivation algorithms are used:

- HMAC (Hash-based Message Authentication Code)

- PBKDF2 (Password-Based Key Derivation Function 2)

We will explore together the functioning and role of each of them.

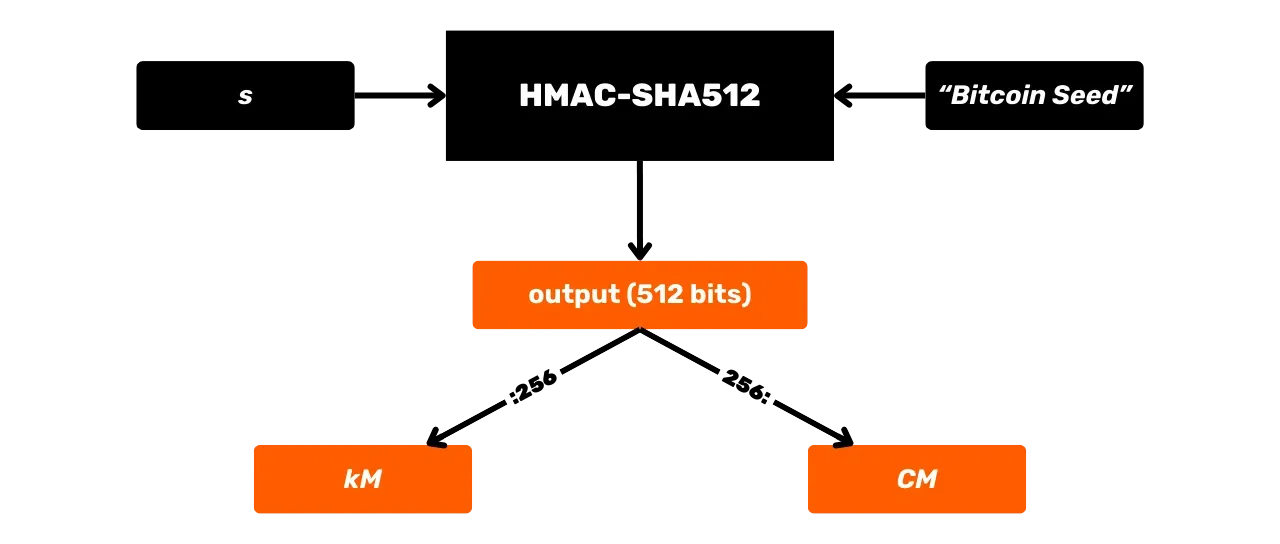

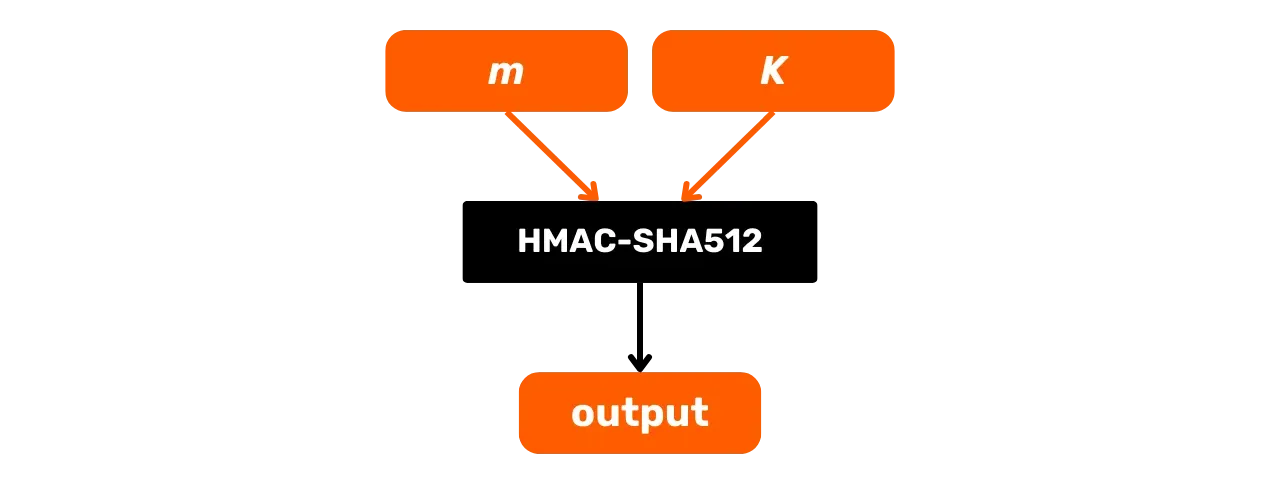

HMAC-SHA512

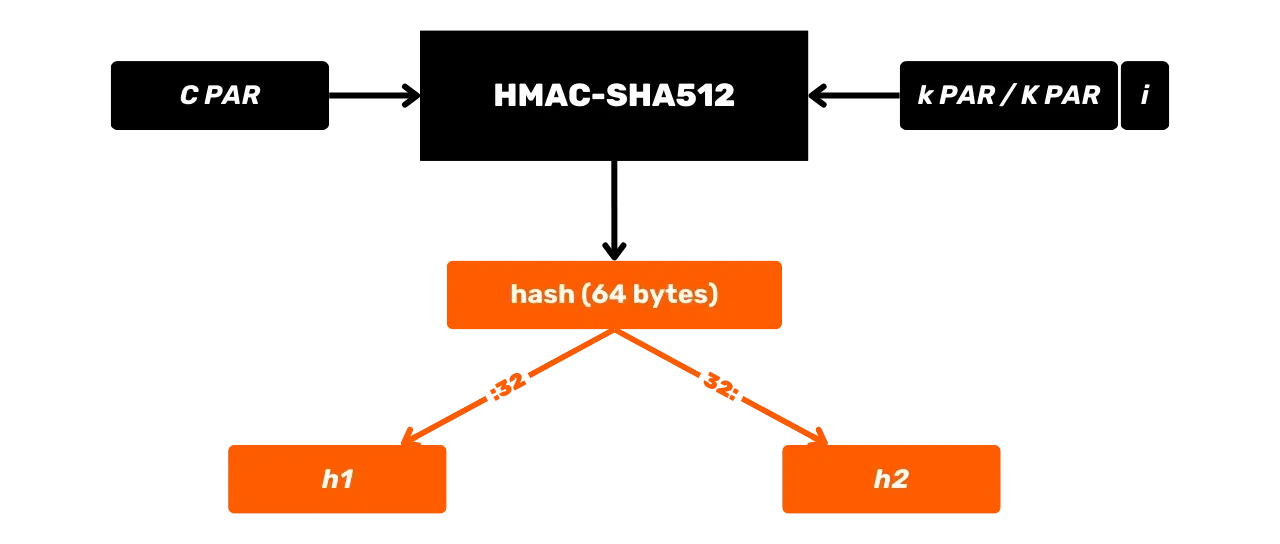

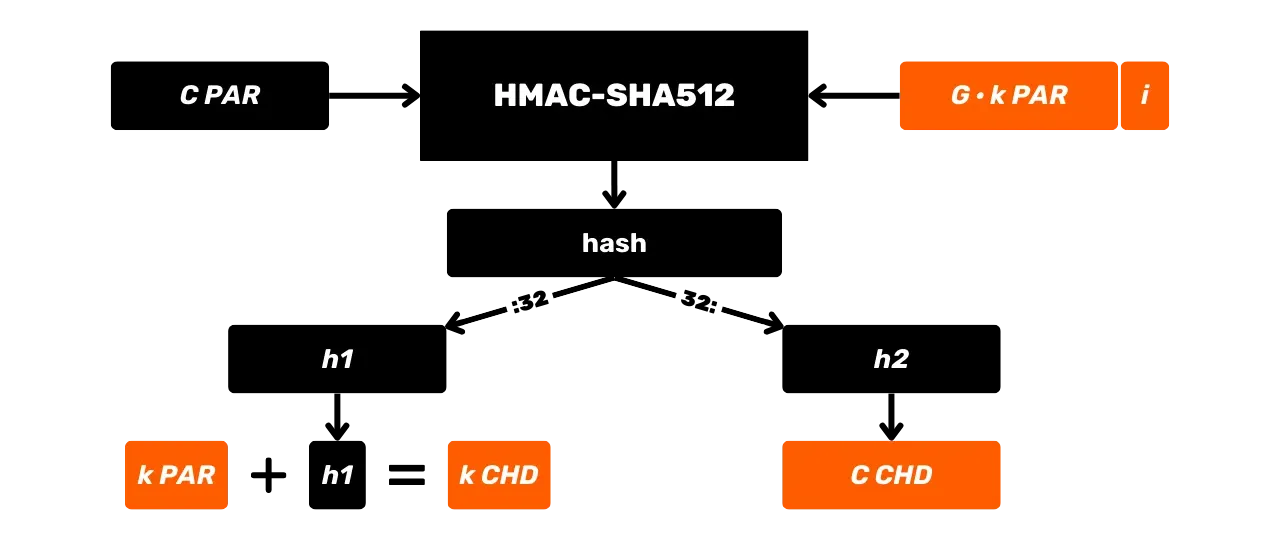

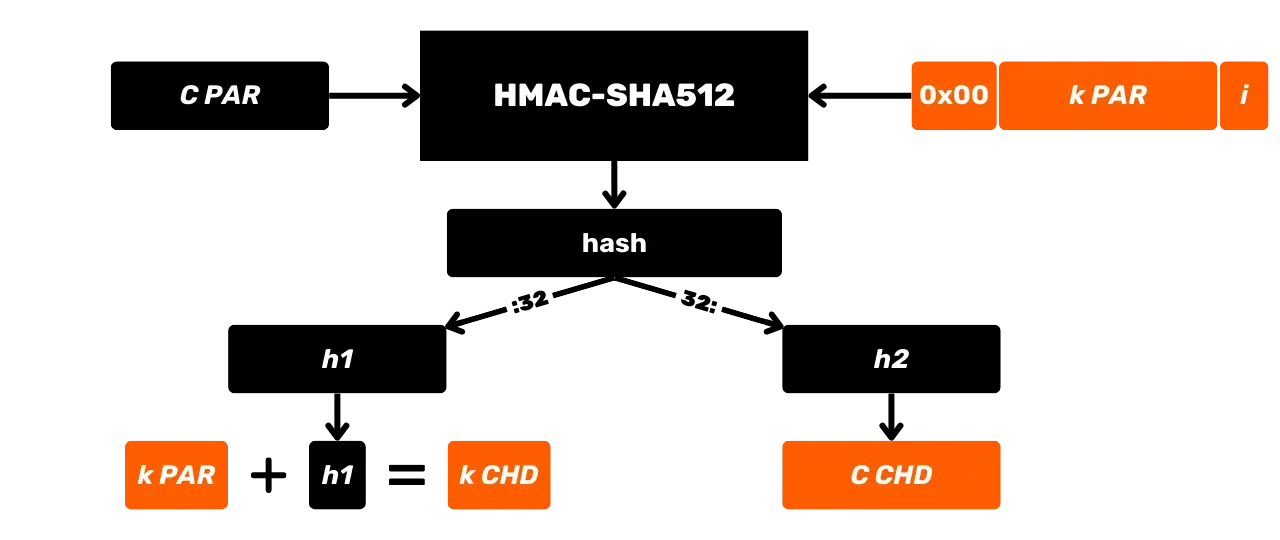

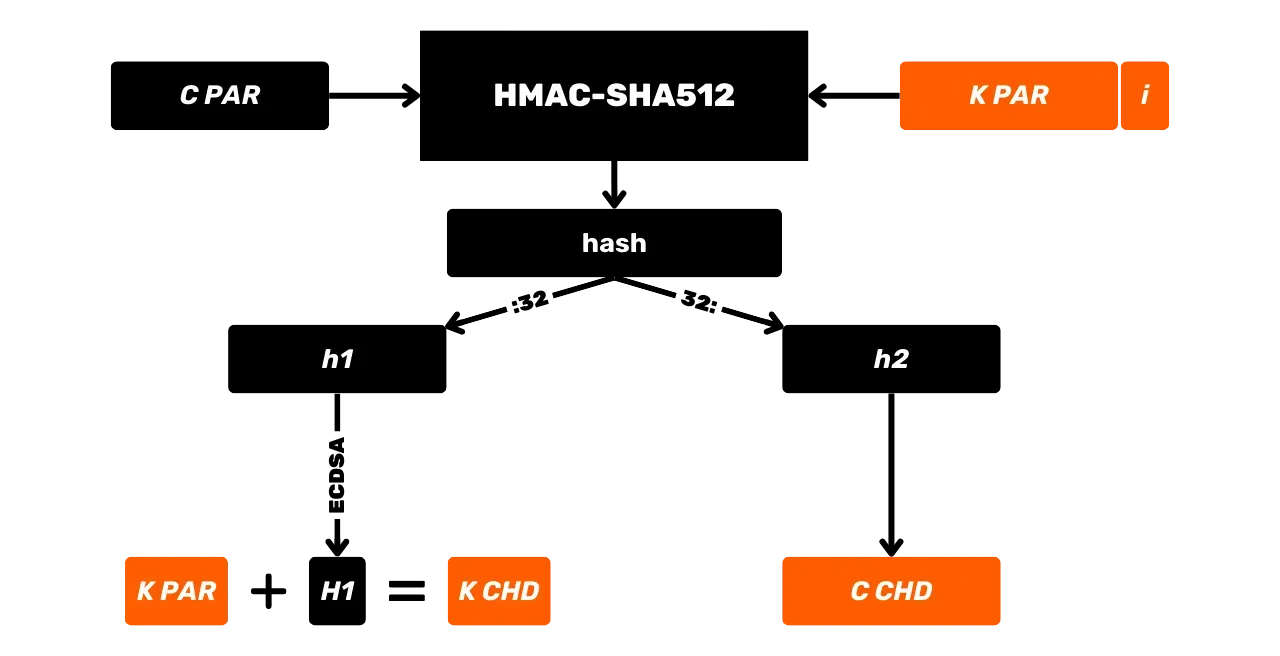

HMAC is a cryptographic algorithm that calculates an authentication code based on a combination of a hash function and a secret key. Bitcoin uses HMAC-SHA512, the variant of HMAC that uses the SHA512 hash function. We have already seen in the previous chapter that SHA512 is part of the same family of hash functions as SHA256, but it produces a 512-bit output.

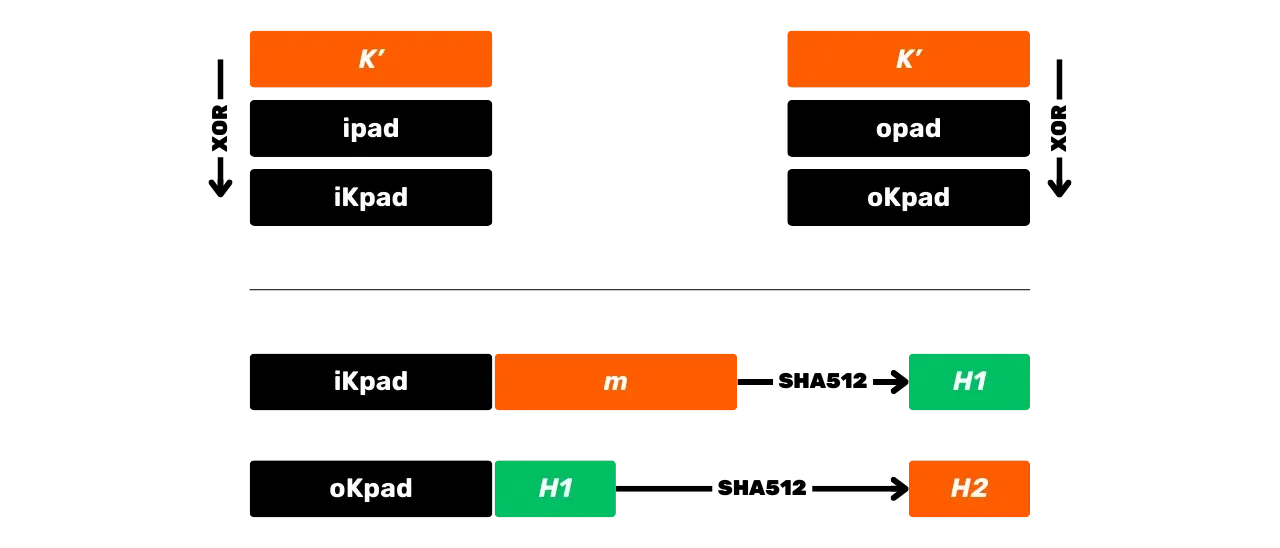

Here is its general operating scheme with m being the input message and K a secret key:

Let's study in more detail what happens in this HMAC-SHA512 black box. The HMAC-SHA512 function with:

m: the arbitrarily sized message chosen by the user (first input);K: the arbitrary secret key chosen by the user (second input);K': the keyKadjusted to the sizeBof the hash function blocks (1024 bits for SHA512, or 128 bytes);\text{SHA512}: the SHA512 hash function;\oplus: the XOR (exclusive or) operation;\Vert: the concatenation operator, linking bit strings end-to-end;\text{opad}: constant composed of the byte0x5crepeated 128 times\text{ipad}: constant composed of the byte0x36repeated 128 times.

Before calculating the HMAC, it is necessary to equalize the key and

constants according to the block size B. For example, if the key K is shorter than 128 bytes, it is padded with zeros to reach the size B. If K is longer than 128 bytes, it is compressed using SHA512, and then zeros are

added until it reaches 128 bytes. In this way, an equalized key named K' is obtained. The values of \text{opad} and \text{ipad} are

obtained by repeating their base byte (0x5c for \text{opad}, 0x36 for \text{ipad})

until the size B is reached.

Thus, with B = 128 bytes, we have:

\text{opad} = \underbrace{0x5c5c\ldots5c}\_{128 \ \text{bytes}}

Once the preprocessing is done, the HMAC-SHA512 algorithm is defined by the following equation:

\text{HMAC-SHA512}(K,m) = \text{SHA512} \left( (K' \oplus \text{opad}) \parallel \text{SHA512} \left( (K' \oplus \text{ipad}) \parallel m \right) \right)

This equation is broken down into the following steps:

- XOR the adjusted key

K'with\text{ipad}to obtain\text{iKpad}; - XOR the adjusted key

K'with\text{opad}to obtain\text{oKpad}; - Concatenate

\text{iKpad}with the messagem. - Hash this result with SHA512 to obtain an intermediate hash

H_1. - Concatenate

\text{oKpad}withH_1. - Hash this result with SHA512 to obtain the final result

H_2.

These steps can be summarized schematically as follows:

HMAC is used in Bitcoin notably for key derivation in HD (Hierarchical Deterministic) wallets (we will talk about this in more detail in the coming chapters) and as a component of PBKDF2.

PBKDF2

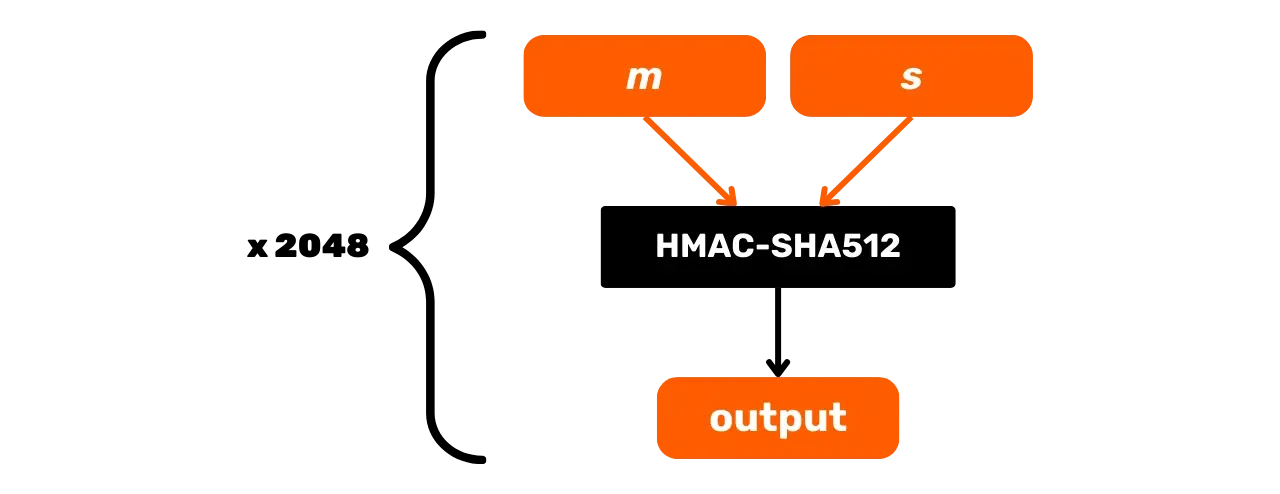

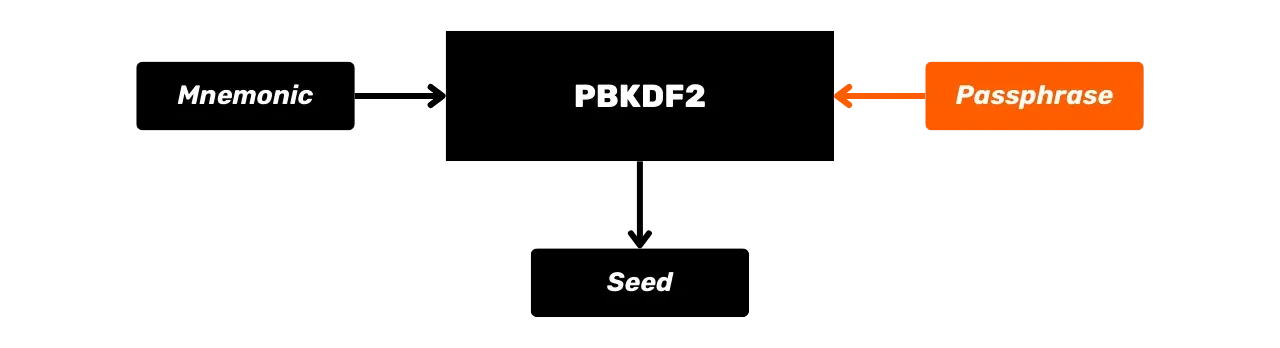

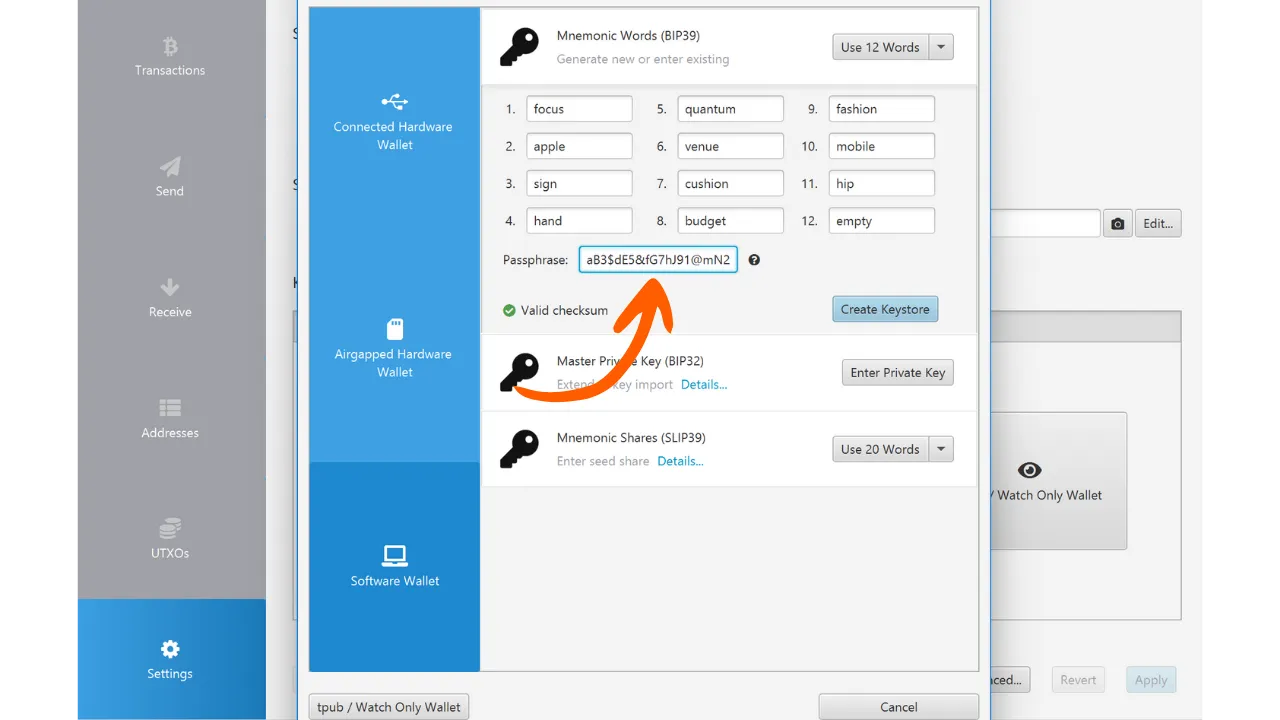

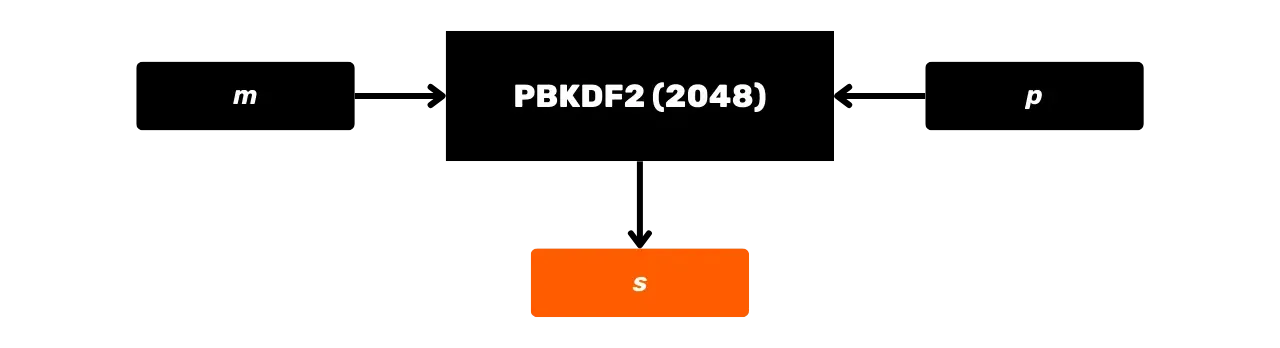

PBKDF2 (Password-Based Key Derivation Function 2) is a key derivation algorithm designed to enhance the security of passwords. The algorithm applies a pseudo-random function (here HMAC-SHA512) on a password and a cryptographic salt, and then repeats this operation a certain number of times to produce an output key.

In Bitcoin, PBKDF2 is used to generate the seed of an HD wallet from a mnemonic phrase and a passphrase (but we will talk about this in more detail in the coming chapters).

The PBKDF2 process is as follows, with:

m: the user's mnemonic phrase;s: the optional passphrase to increase security (empty field if no passphrase);n: the number of iterations of the function, in our case, it's 2048.

The PBKDF2 function is defined iteratively. Each iteration takes the result of the previous one, passes it through HMAC-SHA512, and combines the successive results to produce the final key:

\text{PBKDF2}(m, s) = \text{HMAC-SHA512}^{2048}(m, s)

Schematically, PBKDF2 can be represented as follows:

In this chapter, we have explored the HMAC-SHA512 and PBKDF2 functions, which use hashing functions to ensure the integrity and security of key derivations in the Bitcoin protocol. In the next part, we will look into digital signatures, another cryptographic method widely used in Bitcoin.

Digital Signatures

Digital Signatures and Elliptic Curves

The second cryptographic method used in Bitcoin involves digital signature algorithms. Let's explore what this entails and how it works.

Bitcoins, UTXOs, and Spending Conditions

The term "wallet" in Bitcoin can be quite confusing for beginners. Indeed, what is called a Bitcoin wallet is software that does not directly hold your bitcoins, unlike a physical wallet that can hold coins or bills. Bitcoins are simply units of account. This unit of account is represented by UTXO (Unspent Transaction Outputs), which are unspent transaction outputs. If these outputs are unspent, it means they belong to a user. UTXOs are, in a way, pieces of bitcoins, of variable size, belonging to a user.

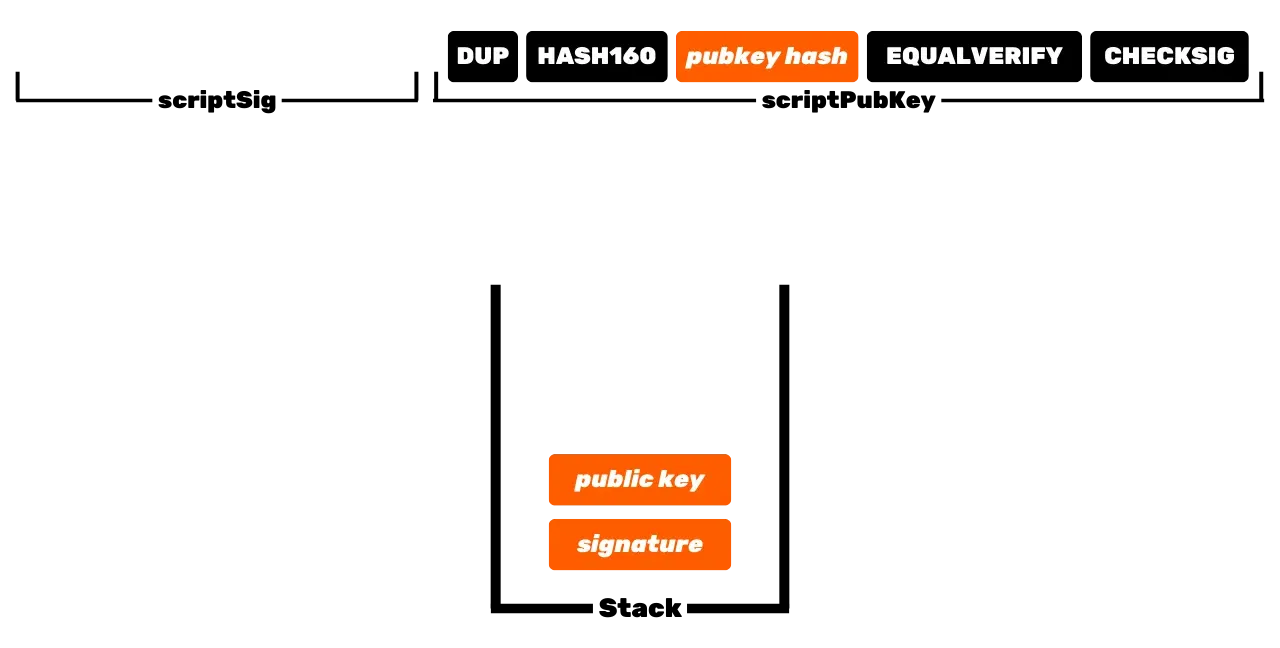

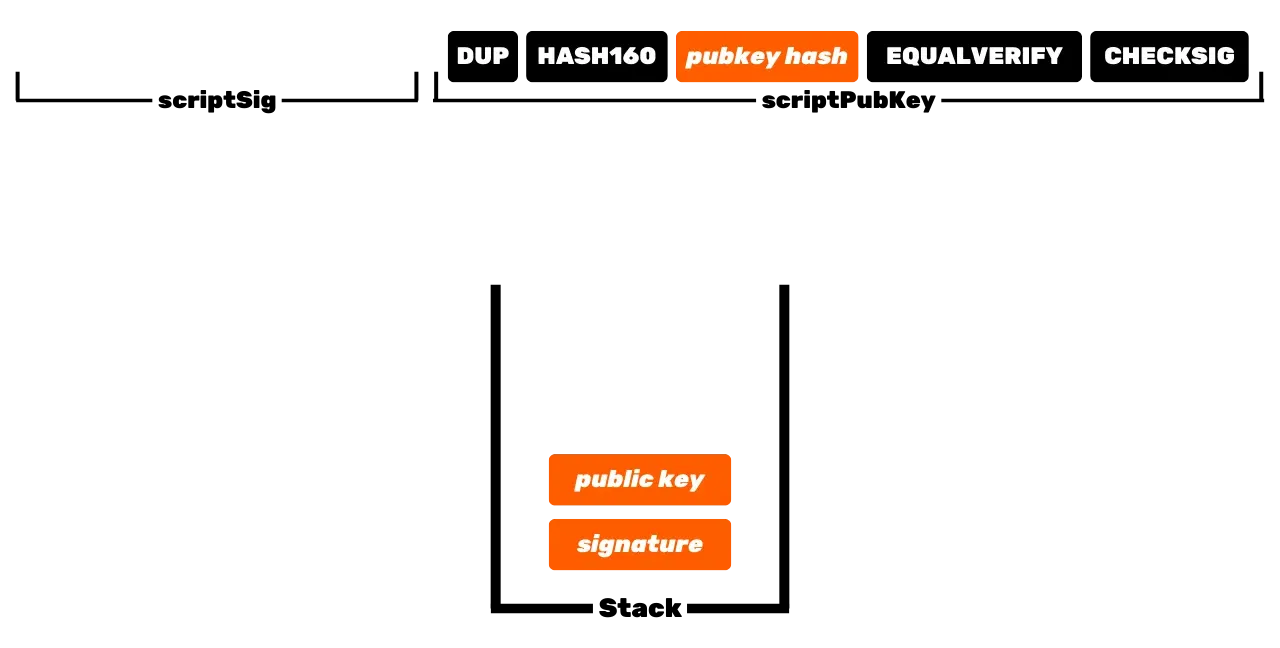

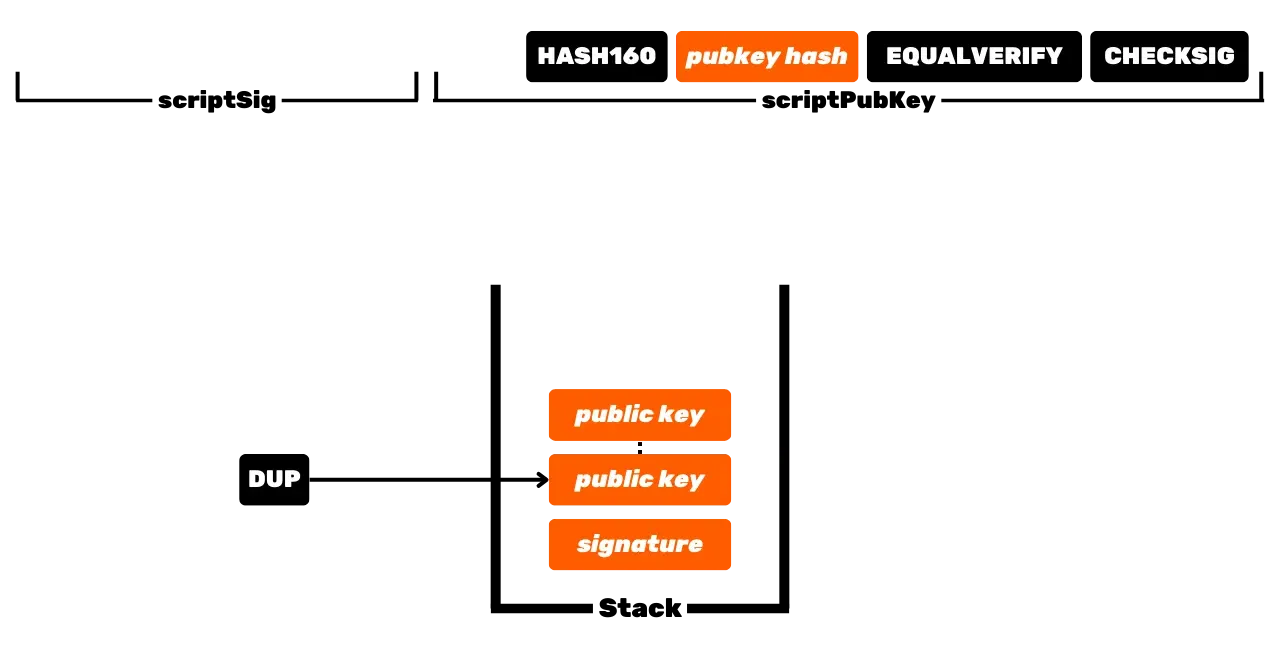

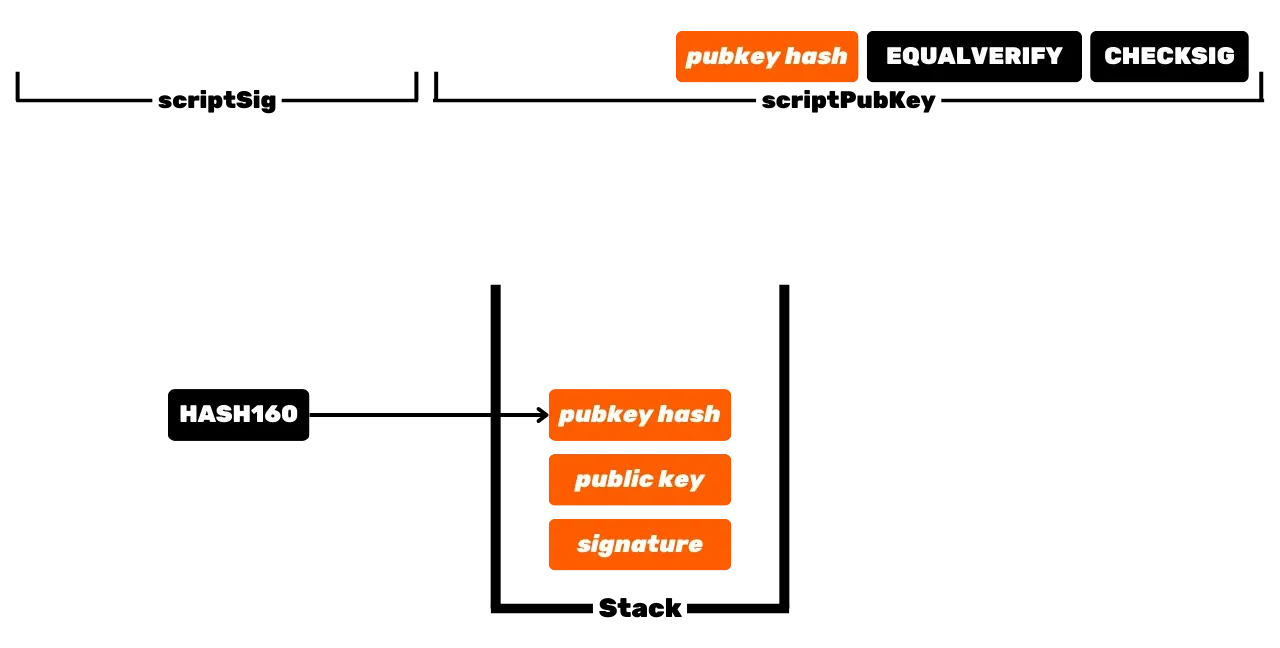

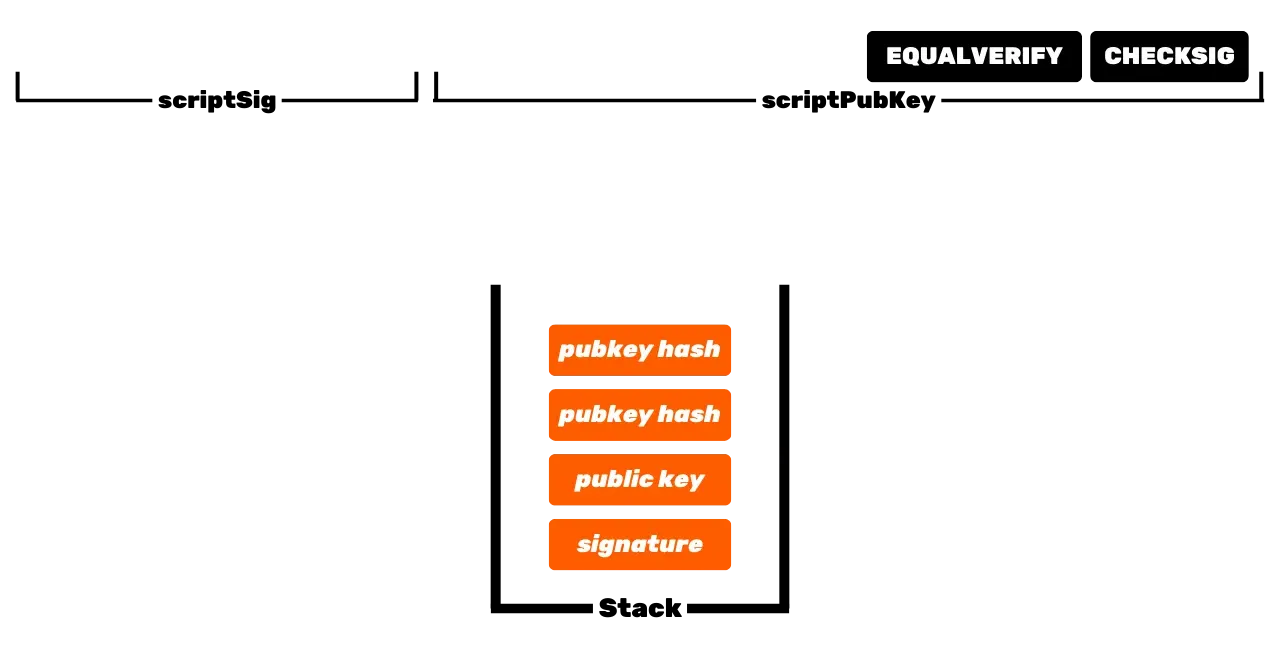

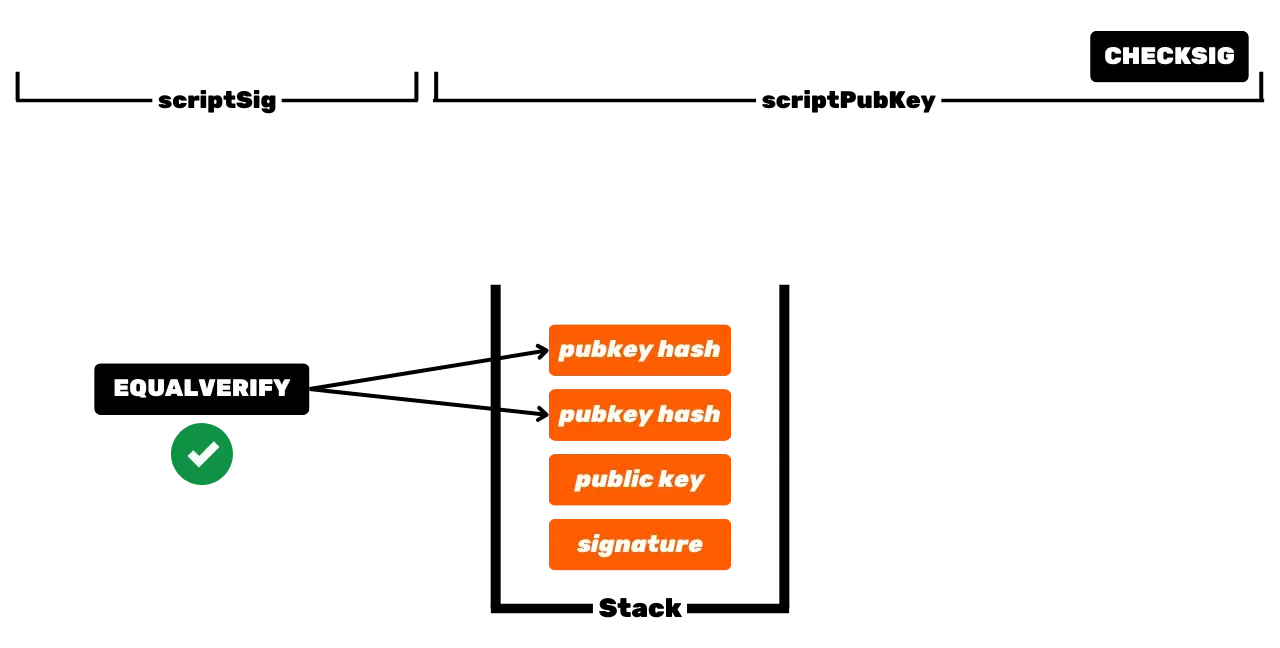

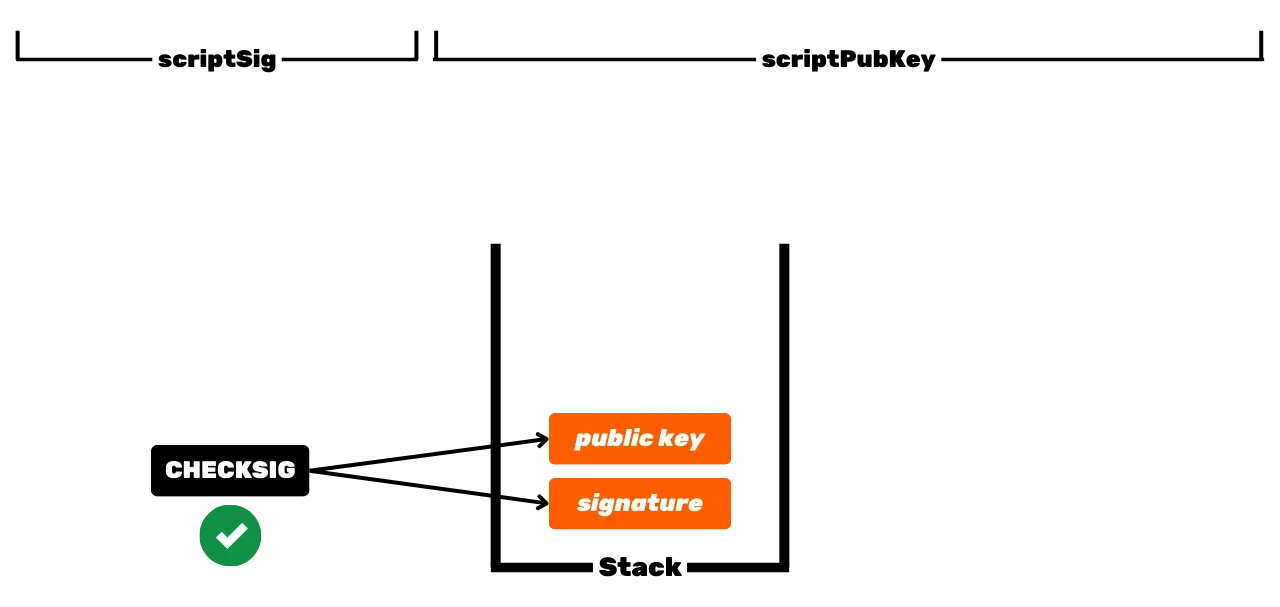

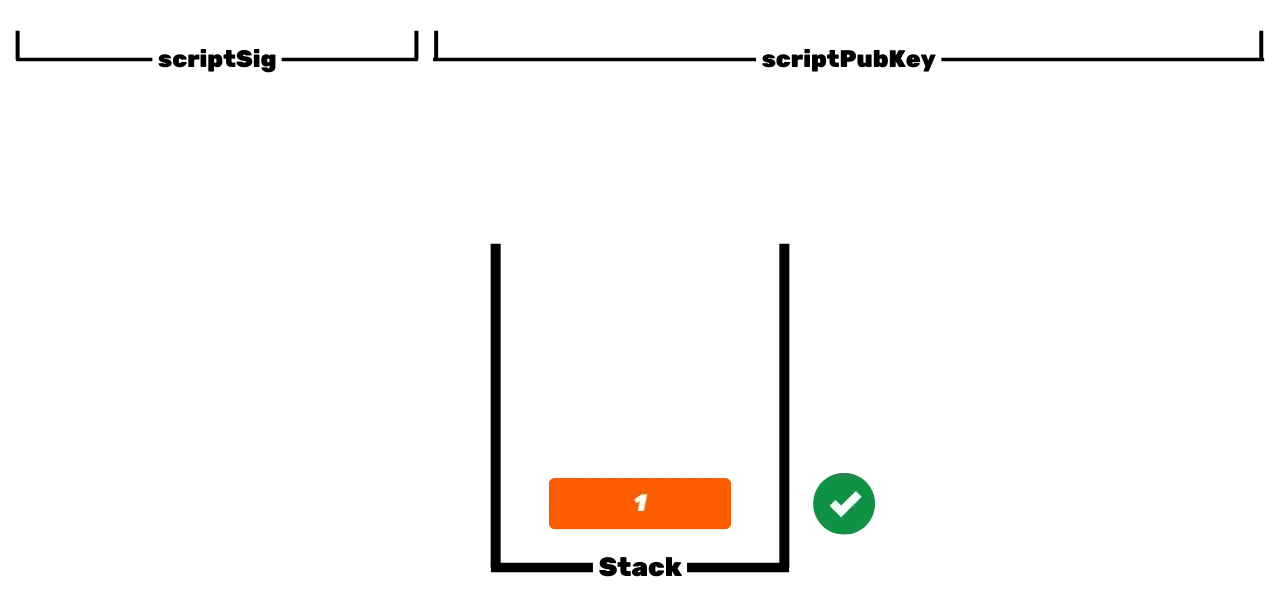

The Bitcoin protocol is distributed and operates without a central authority. Therefore, it is not like traditional banking records, where the euros that belong to you are simply associated with your personal identity. In Bitcoin, your UTXOs belong to you because they are protected by spending conditions specified in the Script language. To simplify, there are two types of scripts: the locking script (scriptPubKey), which protects a UTXO, and the unlocking script (scriptSig), which allows unlocking a UTXO and thus spending the bitcoin units it represents. The initial operation of Bitcoin with P2PK scripts involves using a public key to lock funds, specifying in a scriptPubKey that the person wishing to spend this UTXO must provide a valid signature with the private key corresponding to this public key. To unlock this UTXO, it is therefore necessary to provide a valid signature in the scriptSig. As their names suggest, the public key is known to all since it is broadcast on the blockchain, while the private key is only known to the legitimate owner of the funds. This is the basic operation of Bitcoin, but over time, this operation has become more complex. First, Satoshi also introduced P2PKH scripts, which use a receiving address in the scriptPubKey, which represents the hash of the public key. Then, the system became even more complex with the arrival of SegWit and then Taproot. However, the general principle remains fundamentally the same: a public key or a representation of this key is used to lock UTXOs, and a corresponding private key is required to unlock them and thus spend them.

A user who wishes to make a Bitcoin transaction must therefore create a digital signature using their private key on the transaction. The signature can be verified by other network participants. If it is valid, this means that the user initiating the transaction is indeed the owner of the private key, and therefore the owner of the bitcoins they wish to spend. Other users can then accept and propagate the transaction.

As a result, a user who owns bitcoins locked with a public key must find a way to securely store what allows unlocking their funds: the private key. A Bitcoin wallet is precisely a device that will allow you to easily keep all your keys without other people having access to them. It is therefore more like a keychain than a wallet.

The mathematical link between a public key and a private key, as well as the ability to perform a signature to prove the possession of a private key without revealing it, are made possible by a digital signature algorithm. In the Bitcoin protocol, two signature algorithms are used: ECDSA (Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm) and the Schnorr signature scheme. ECDSA is the digital signature protocol used in Bitcoin from its beginnings. Schnorr is more recent in Bitcoin, as it was introduced in November 2021 with the Taproot update. These two algorithms are quite similar in their mechanisms. They are both based on elliptic curve cryptography. The major difference between these two protocols lies in the structure of the signature and some specific mathematical properties. We will therefore study the functioning of these algorithms, starting with the oldest: ECDSA.

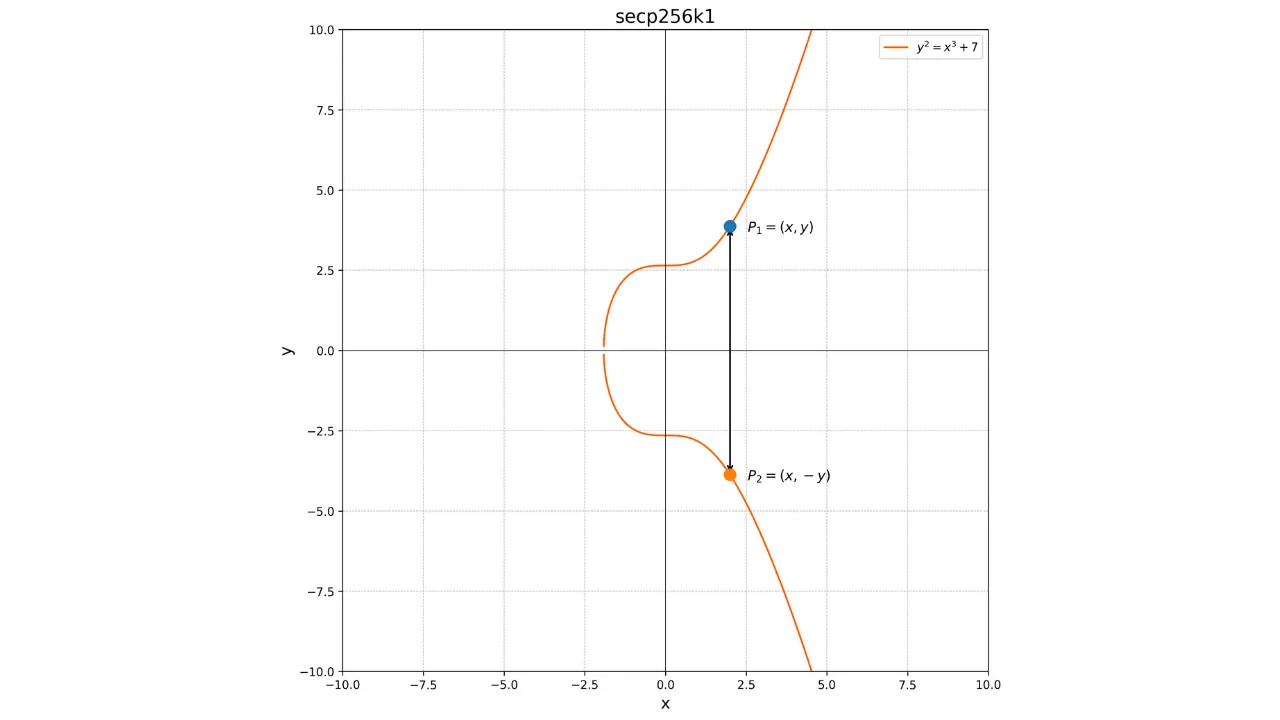

Elliptic Curve Cryptography

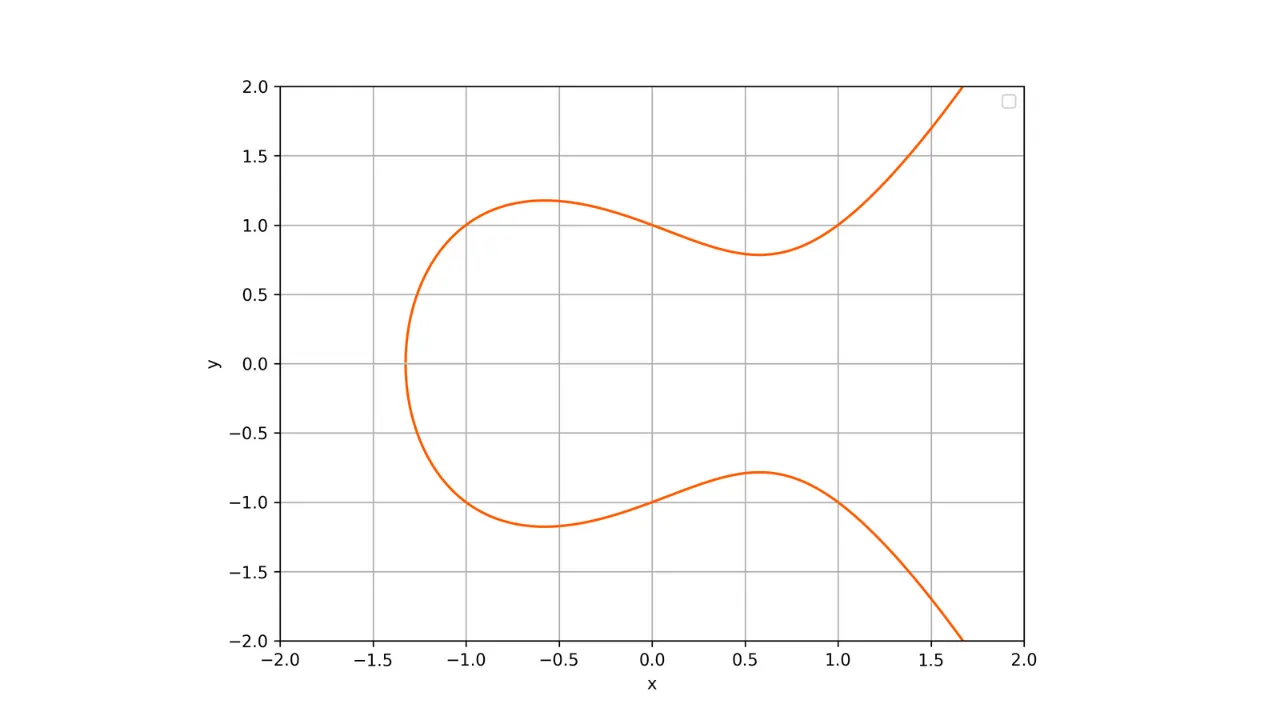

Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) is a set of algorithms that use an elliptic curve for its various mathematical and geometric properties for cryptographic purposes. The security of these algorithms relies on the difficulty of the discrete logarithm problem on elliptic curves. Elliptic curves are notably used for key exchanges, asymmetric encryption, or for creating digital signatures.

An important property of these curves is that they are symmetric with respect to the x-axis. Thus, any non-vertical line cutting the curve at two distinct points will always intersect the curve at a third point. Moreover, any tangent to the curve at a non-singular point will intersect the curve at another point. These properties will be useful for defining operations on the curve.

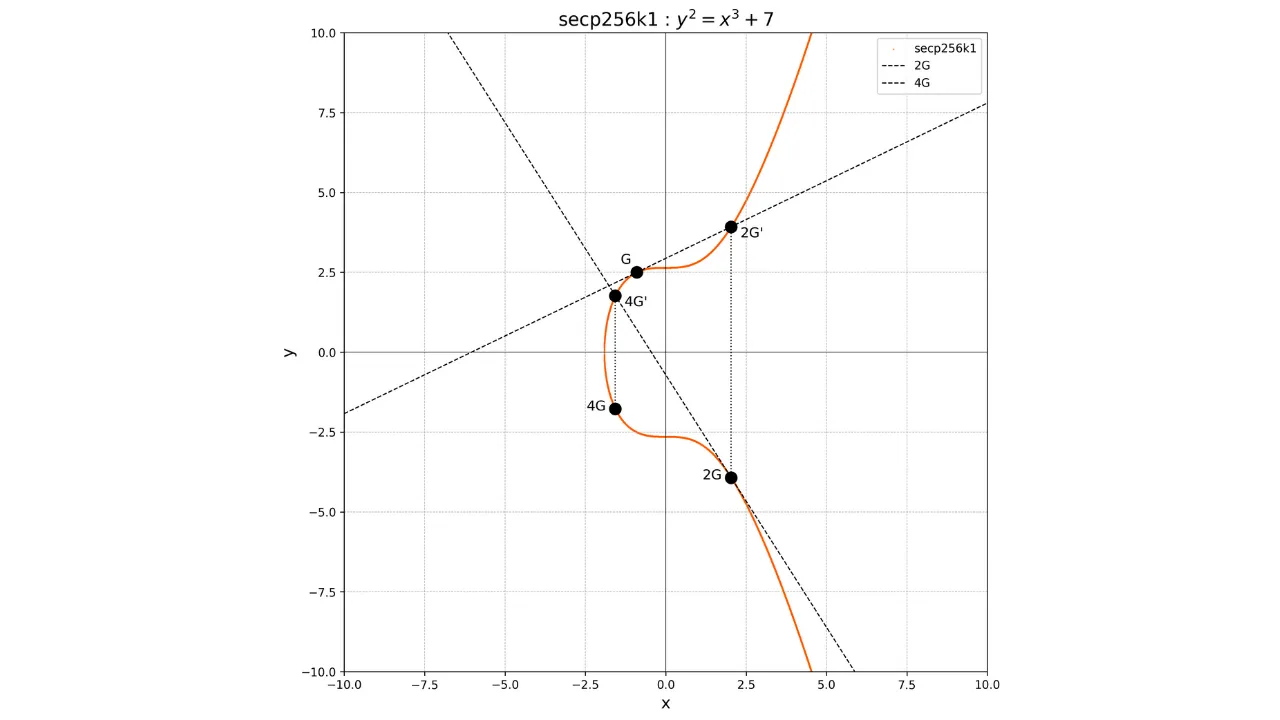

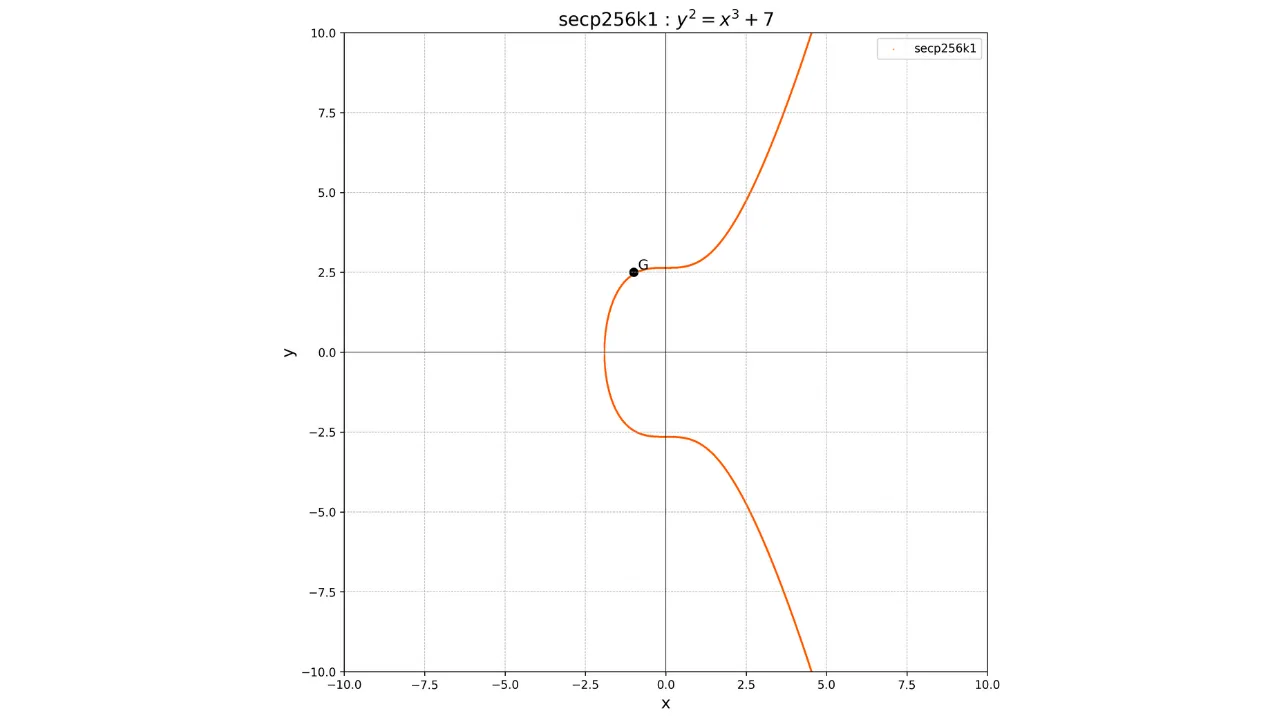

Here is a representation of an elliptic curve over the field of real numbers:

Every elliptic curve is defined by an equation of the form:

y^2 = x^3 + ax + b

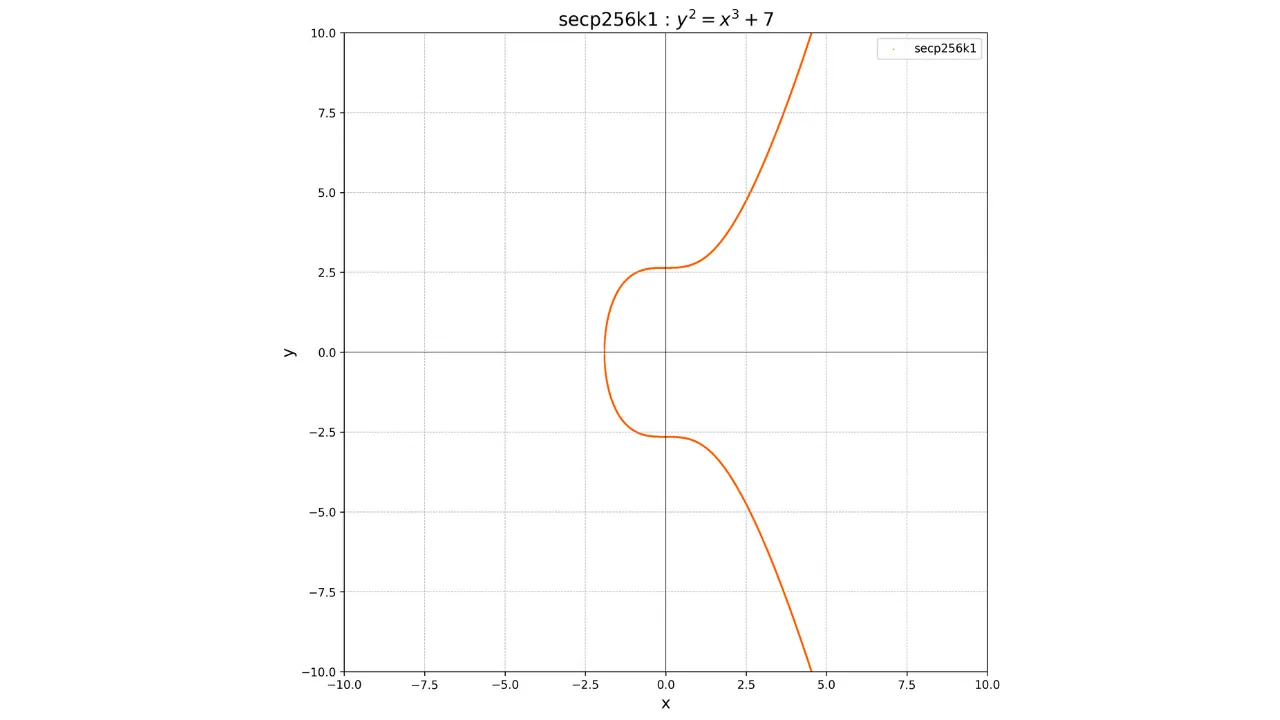

secp256k1

To use ECDSA or Schnorr, one must choose the parameters of the elliptic

curve, that is, the values of a and b in the curve equation.

There are different standards of elliptic curves that are reputed to be

cryptographically secure. The most well-known is the secp256r1 curve, defined and recommended by the NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology).

Despite this, Satoshi Nakamoto, the inventor of Bitcoin, chose not to use

this curve. The reason for this choice is unknown, but some believe he

preferred to find an alternative because the parameters of this curve could

potentially contain a backdoor. Instead, the Bitcoin protocol uses the

standard secp256k1 curve. This curve is defined by

the parameters a = 0 and b = 7. Its equation is

therefore:

y^2 = x^3 + 7

Its graphical representation over the field of real numbers looks like this:

However, in cryptography, we work with finite sets of numbers. More

specifically, we work on the finite field \mathbb{F}_p, which is the field of integers modulo a prime number p. Definition: A prime number is a natural integer greater

than or equal to 2 that has only two distinct positive integer divisors: 1

and itself. For example, the number 7 is a prime number since it can only be

divided by 1 and 7. On the other hand, the number 8 is not prime because it

can be divided by 1, 2, 4, and 8. In Bitcoin, the prime number p used to define the finite field is very large. It is chosen in such a way

that the order of the field (i.e., the number of elements in \mathbb{F}_p) is

sufficiently large to ensure cryptographic security.

The prime number p used is:

p = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEFFFFFC2F

In decimal notation, this corresponds to:

p = 2^{256} - 2^{32} - 977

Thus, the equation of our elliptic curve is actually:

y^2 \equiv x^3 + 7 \mod p

Given that this curve is defined over the finite field \mathbb{F}_p, it no longer resembles a continuous curve but rather a discrete set of

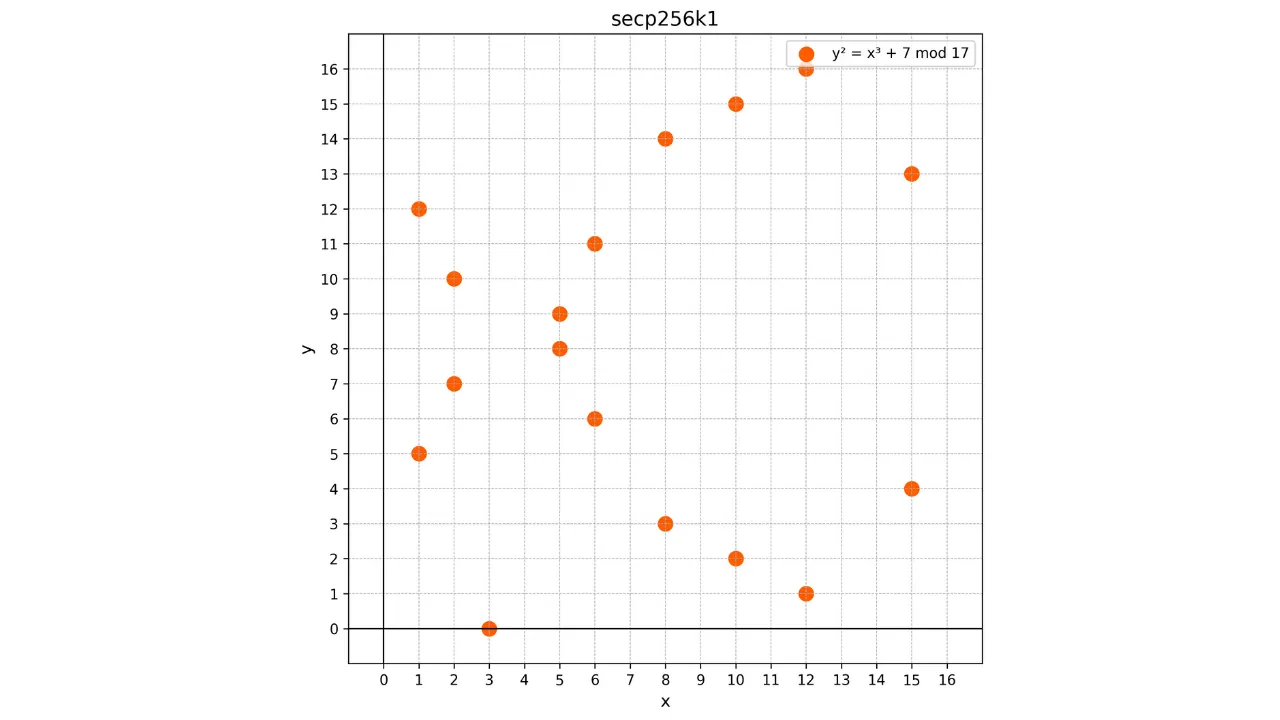

points. For example, here is what the curve used in Bitcoin looks like for a

very small p = 17:

In this example, I have intentionally limited the finite field to p = 17 for educational reasons, but one must imagine that the one used in Bitcoin

is immensely larger, almost 2^{256}.

We use a finite field of integers modulo p to ensure the accuracy of operations on the curve. Indeed, elliptic curves

over the field of real numbers are subject to inaccuracies due to rounding errors

during computational calculations. If numerous operations are performed on the

curve, these errors accumulate and the final result can be incorrect or difficult

to reproduce. The exclusive use of positive integers ensures perfect accuracy

of calculations and thus reproducibility of the result.

The mathematics of elliptic curves over finite fields are analogous to those

over the field of real numbers, with the adaptation that all operations are

performed modulo p. To

simplify explanations, we will continue in the following chapters to

illustrate concepts using a curve defined over real numbers, while keeping

in mind that, in practice, the curve is defined over a finite field.

If you wish to learn more about the mathematical foundations of modern cryptography, I also recommend consulting this other course on Plan ₿ Network:

https://planb.network/courses/d2fd9fc0-d9ed-4a87-9fa3-0fdbb3937e28

Calculating the Public Key from the Private Key

fcb2bd58-5dda-5ecf-bb8f-ad1a0561ab4a As previously seen, the digital signature algorithms in Bitcoin are based on a pair of private and public keys that are mathematically linked. Let's explore together what this mathematical link is and how they are generated.

The Private Key

The private key is simply a random or pseudo-random number. In the case of

Bitcoin, this number is 256 bits in size. The number of possibilities for a

Bitcoin private key is therefore theoretically 2^{256}.

Note: A "pseudo-random number" is a number that has properties close to those of a truly random number but is generated by a deterministic algorithm.

However, in practice, there are only n distinct points on our elliptic curve secp256k1, where n is the order of the generator point G of the curve. We will see later what this number corresponds to, but simply

remember that a valid private key is an integer between 1 and n-1, knowing that n is a number close to but slightly less than 2^{256}. Therefore,

there are some 256-bit numbers that are not valid for becoming a private key

in Bitcoin, specifically, all the numbers between n and 2^{256}. If the

generation of the random number (the private key) produces a value k such that k \geq n, it is

considered invalid, and a new random value must be generated.

The number of possibilities for a Bitcoin private key is therefore about n, which is a number close to 1.158 \times 10^{77}. This number is so large that if you choose a private key at random, it is

statistically almost impossible to land on another user's private key. To

give you an idea of scale, the number of possible private keys in Bitcoin is

of an order of magnitude close to that of the estimated atoms in the

observable universe.

As we will see in the coming chapters, today, the majority of private keys used in Bitcoin are not generated randomly but are the result of deterministic derivation from a mnemonic phrase, itself pseudo-random (this is the famous phrase of 12 or 24 words). This information does not change anything for the use of signature algorithms like ECDSA, but it helps to refocus our popularization in Bitcoin.

For the rest of the explanation, the private key will be denoted by the

lowercase letter k.

The Public Key

The public key is a point on the elliptic curve, denoted by the capital

letter K, and is calculated

from the private key k. This

point K is represented by a

pair of coordinates (x, y) on

the elliptic curve, each coordinate being an integer modulo p, the prime number defining

the finite field \mathbb{F}_p. In

practice, an uncompressed public key is represented by 520 bits (or 65

bytes), corresponding to two 256-bit numbers (x and y) placed end-to-end,

preceded by the 8-bit prefix 0x04.

However, it is also possible to represent the public key in a compressed

form using only 33 bytes (264 bits) by keeping only the abscissa x of our point on the curve and a byte indicating the parity of y. This is what is known as a

compressed public key. I will talk more about this in the last chapters of

this training. But what you need to remember is that a public key K is a point described by x and y.

To calculate the point K that

corresponds to our public key, we use the operation of scalar multiplication

on elliptic curves, defined as a repeated addition (k times) of the generator point G:

K = k \cdot G

where:

kis the private key (a random integer between1andn-1);Gis the generator point of the elliptic curve used by all participants of the Bitcoin network;\cdotrepresents the scalar multiplication on the elliptic curve, which is equivalent to adding the pointGto itselfktimes.

The fact that this point G is

common to all public keys in Bitcoin allows us to be sure that the same

private key k will always

give us the same public key K:

The main characteristic of this operation is that it is a one-way function.

It is easy to calculate the public key K knowing the private key k and

the generator point G, but it

is practically impossible to calculate the private key k knowing only the public key K and the generator point G.

Finding k from K and G amounts to solving the discrete

logarithm problem on elliptic curves, a mathematically difficult problem for

which no efficient algorithm is known. Even the most powerful current calculators

are unable to solve this problem in a reasonable time.

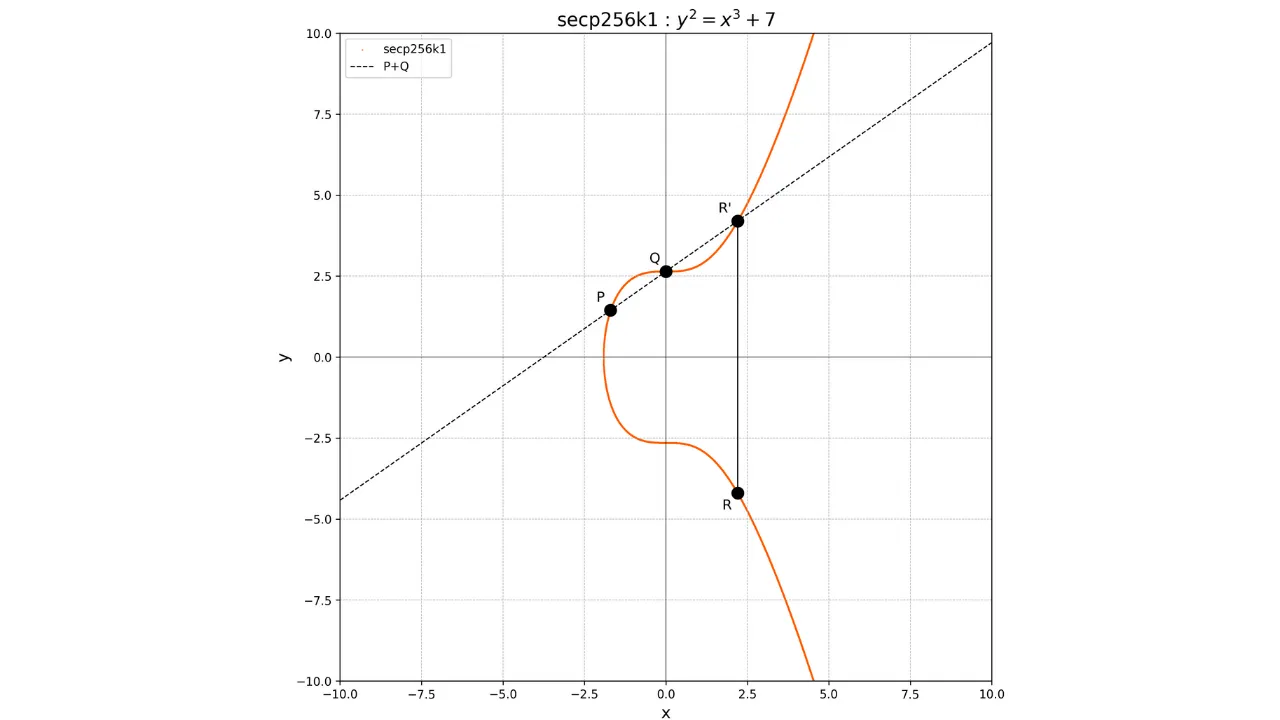

Addition and Doubling of Points on Elliptic Curves

The concept of addition on elliptic curves is defined geometrically. If we

have two points P and Q on the curve, the operation P + Q is calculated by drawing a line passing through P and Q. This line will

necessarily intersect the curve at a third point R'. We then take the mirror

image of this point with respect to the x-axis to obtain the point R, which is the result of the

addition:

P + Q = R

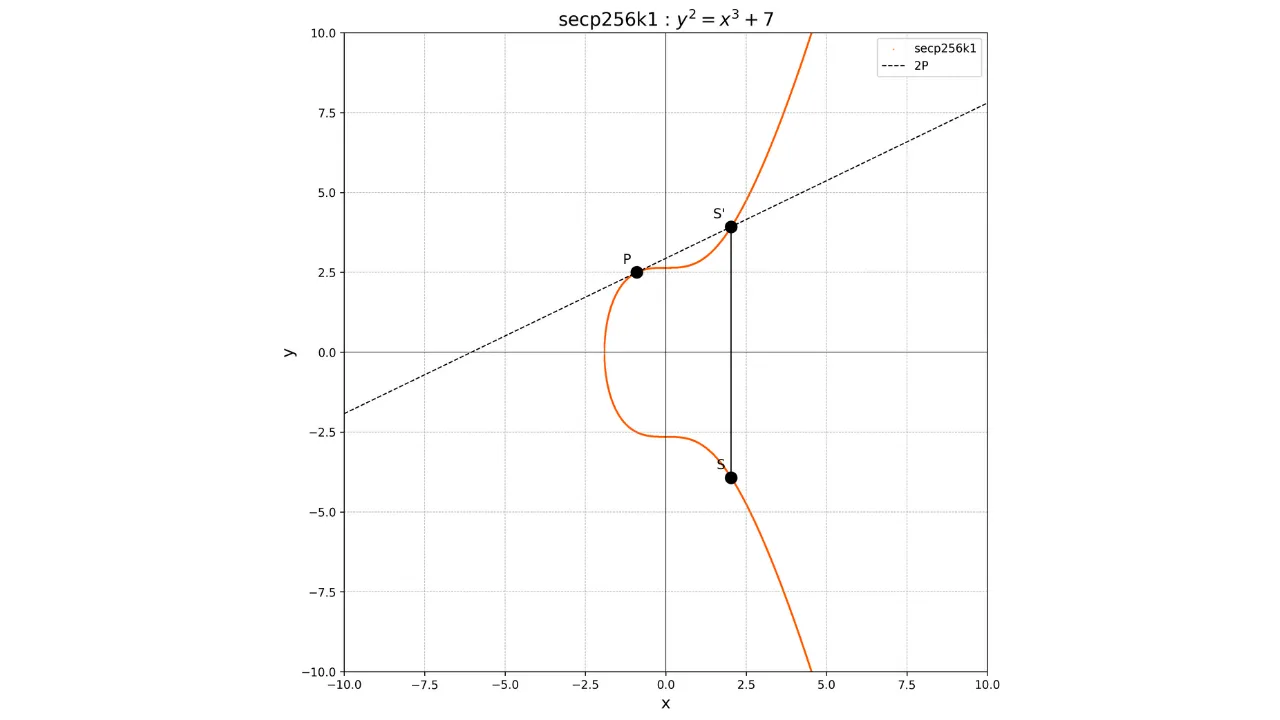

Graphically, this can be represented as follows:

For the doubling of a point, that is the operation P + P, we draw the tangent to the curve at point P. This tangent intersects

the curve at another point S'. We then take the mirror

image of this point with respect to the x-axis to obtain the point S, which is the result of the

doubling:

2P = S

Graphically, this is shown as:

By using these operations of addition and doubling, we can perform the

scalar multiplication of a point by an integer k, denoted kP, by performing

repeated doublings and additions.

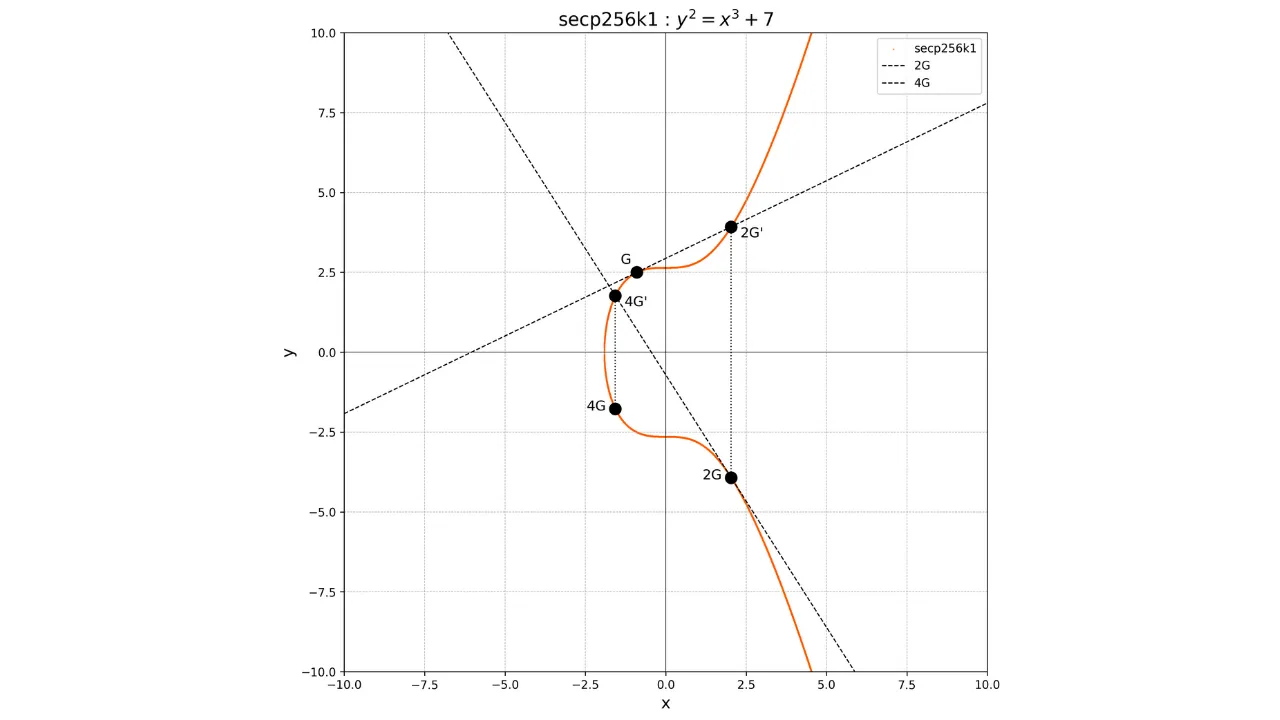

For example, suppose we have chosen a private key k = 4. To compute the associated public key, we perform:

K = k \cdot G = 4G

Graphically, this corresponds to performing a series of additions and doublings:

- Calculate

2Gby doublingG. - Calculate

4Gby doubling2G.

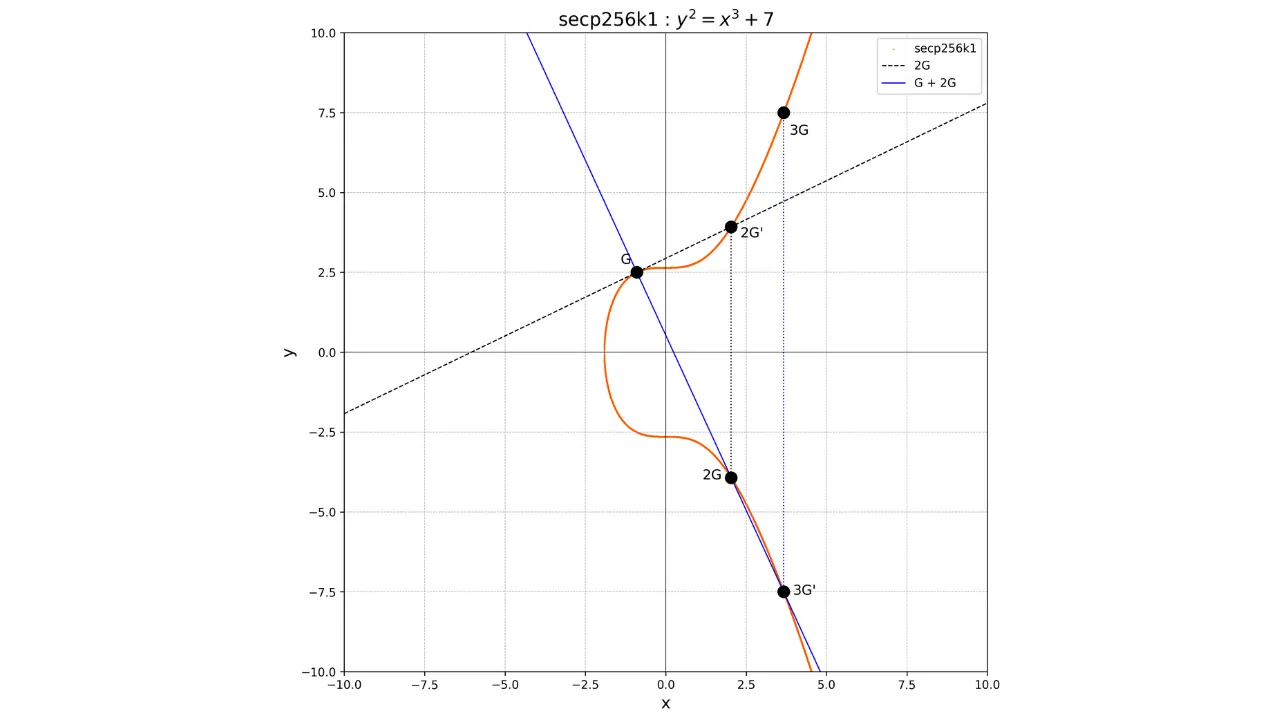

If we wish, for example, to calculate the point 3G, we must first calculate the point 2G by doubling the point G, then

add G and 2G. To add G and 2G, simply draw the line

connecting these two points, retrieve the unique point -3G at the intersection between this line and the elliptic curve, and then

determine 3G as the opposite

of -3G.

We will have:

G + G = 2G

2G + G = 3G

Graphically, this would be represented as follows:

One-Way Function

Thanks to these operations, we can understand why it is easy to derive a public key from a private key, but the reverse is practically impossible.

Let's go back to our simplified example. With a private key k = 4. To calculate the associated public key, we perform:

K = k \cdot G = 4GWe have thus been able to easily calculate the public key K by knowing k and G.

Now, if someone only knows the public key K, they are faced with the discrete logarithm problem: finding k such that K = k \cdot G. This

problem is considered difficult because there is no efficient algorithm to

solve it on elliptic curves. This ensures the security of the ECDSA and

Schnorr algorithms.

Of course, in this simplified example with k = 4, it would be possible to find k through trial and error, as the number of possibilities is low. However, in

practice, k is a 256-bit

integer, making the number of possibilities astronomically large (about 1.158 \times 10^{77}). Therefore, it is infeasible to find k by brute force.

Signing with the Private Key

Now that you know how to derive a public key from a private key, you can

already receive bitcoins by using this pair of keys as a spending condition.

But how to spend them? To spend bitcoins, you will need to unlock the scriptPubKey attached to your UTXO to prove that you are indeed its legitimate owner. To

do this, you must produce a signature s that matches the public key K present in the scriptPubKey using the private key k that was initially used to calculate K. The digital signature is

thus irrefutable proof that you are in possession of the private key

associated with the public key you claim.

Elliptic Curve Parameters

To perform a digital signature, all participants must first agree on the parameters of the elliptic curve used. In the case of Bitcoin, the parameters of secp256k1 are as follows:

The finite field \mathbb{Z}_p defined by:

p = 2^{256} - 2^{32} - 977p = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEFFFFFC2F

p is a very large prime

number slightly less than 2^{256}.

The elliptic curve y^2 = x^3 + ax + b over \mathbb{Z}_p defined

by:

a = 0, \quad b = 7The generator point or origin point G:

G = 0x0279BE667EF9DCBBAC55A06295CE870B07029BFCDB2DCE28D959F2815B16F81798

This number is the compressed form that only gives the abscissa of point G. The prefix 02 at the beginning determines which of the two

values having this abscissa x is to be used as the generating point. The order n of G (the number of existing

points) and the cofactor h:

n = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFEBAAEDCE6AF48A03BBFD25E8CD0364141

n is a very large number

slightly less than p.

h=1h is the cofactor or the

number of subgroups. I will not elaborate on what this represents here, as

it’s quite complex, and in the case of Bitcoin, we do not need to take it

into account since it is equal to 1.

All this information is public and known to all participants. Thanks to them, users are able to make a digital signature and verify it.

Signature with ECDSA

The ECDSA algorithm allows a user to sign a message using their private key, in such a way that anyone knowing the corresponding public key can verify the validity of the signature, without the private key ever being revealed. In the context of Bitcoin, the message to be signed depends on the sighash chosen by the user. It is this sighash that will determine which parts of the transaction are covered by the signature. I will talk more about this in the next chapter.

Here are the steps to generate an ECDSA signature:

First, we calculate the hash (e) of the message that needs to be signed. The message m is thus passed through a cryptographic

hash function, generally SHA256 or double SHA256 in the case of Bitcoin:

e = \text{HASH}(m)Next, we calculate a nonce. In cryptography, a nonce is simply a number

generated in a random or pseudo-random manner that is used only once. That

is to say, each time a new digital signature is made with this pair of keys,

it will be very important to use a different nonce, otherwise, it will

compromise the security of the private key. It is therefore sufficient to

determine a random and unique integer r such that 1 \leq r \leq n-1,

where n is the order of the

generating point G of the elliptic

curve.

Then, we will calculate the point R on the elliptic curve with the coordinates (x_R, y_R) such that:

R = r \cdot GWe extract the value of the abscissa of the point R (x_R). This value represents

the first part of the signature. And finally, we calculate the second part

of the signature s in this manner:

s = r^{-1} \left( e + k \cdot x_R \right) \mod nwhere:

r^{-1}is the modular inverse ofrmodulon, that is, an integer such thatr \cdot r^{-1} \equiv 1 \mod n;kis the user's private key;eis the hash of the message;nis the order of the generator pointGof the elliptic curve.

The signature is then simply the concatenation of x_R and s:

\text{SIG} = x_R \Vert sVerification of the ECDSA Signature

To verify a signature (x_R, s), anyone knowing the public key K and the parameters of the elliptic

curve can proceed in this way:

First, verify that x_R and s are within the interval [1, n-1]. This ensures that

the signature respects the mathematical constraints of the elliptic group.

If this is not the case, the verifier immediately rejects the signature as

invalid.

Then, calculate the hash of the message:

e = \text{HASH}(m)Calculate the modular inverse of s modulo n:

s^{-1} \mod nCalculate two scalar values u_1 and u_2 in this way:

\begin{align*}

u_1 &= e \cdot s^{-1} \mod n \\

u_2 &= x_R \cdot s^{-1} \mod n

\end{align*}And finally, calculate the point V on the elliptic curve such that:

V = u_1 \cdot G + u_2 \cdot KThe signature is valid only if x_V \equiv x_R \mod n, where x_V is the x coordinate of the point V.

Indeed, by combining u_1 \cdot G and u_2 \cdot K, one obtains

a point V which, if the

signature is valid, must correspond to the point R used during the signature (modulo n).

Signature with the Schnorr Protocol

The Schnorr signature scheme is an alternative to ECDSA that offers many

advantages. It has been possible to use it in Bitcoin since 2021 and the

introduction of Taproot, with the P2TR script patterns. Like ECDSA, the

Schnorr scheme allows signing a message using a private key, in such a way

that the signature can be verified by anyone knowing the corresponding

public key. In the case of Schnorr, the exact same curve as ECDSA is used

with the same parameters. However, public keys are represented slightly

differently compared to ECDSA. Indeed, they are designated only by the x coordinate of the point on the elliptic curve. Unlike ECDSA, where

compressed public keys are represented by 33 bytes (with the prefix byte

indicating the parity of y),

Schnorr uses 32-byte public keys, corresponding only to the x coordinate of the point K,

and it is assumed that y is

even by default. This simplified representation reduces the size of the

signatures and facilitates certain optimizations in the verification

algorithms. The public key is then the x coordinate of the point K:

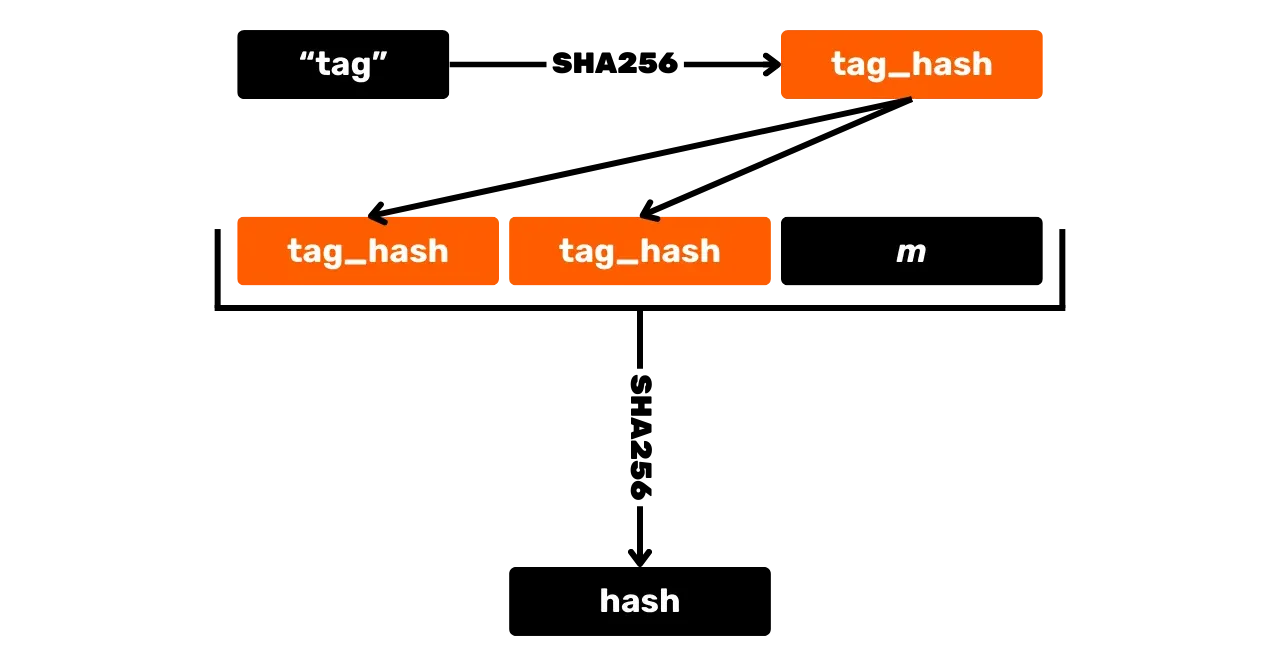

\text{pk} = K_xThe first step to generate a signature is to hash the message. But unlike ECDSA, it is done with other values and a labeled hash function is used to avoid collisions in different contexts. A labeled hash function simply involves adding an arbitrary label to the hash function's inputs alongside the message data.

In addition to the message, the x coordinate of the public key K_x, as well as the point R = r \cdot G, calculated

from the nonce r (which is

itself a unique integer for each signature, calculated deterministically

from the private key and the message to avoid vulnerabilities related to

nonce reuse), are also passed into the labeled function. Just like for the

public key, only the x coordinate of the nonce point R_x is retained to describe the

point.

The result of this hashing noted e is called the "challenge":

e = \text{HASH}(\text{``BIP0340/challenge''}, R_x \Vert K_x \Vert m) \mod nHere, \text{HASH} is the SHA256 hash function, and \text{``BIP0340/challenge''} is the specific tag for the hashing.

Finally, the parameter s is

calculated from the private key k, the nonce r, and the challenge e as follows:

s = (r + e \cdot k) \mod nThe signature is then simply the pair R_x and s.

\text{SIG} = R_x \Vert sVerification of the Schnorr Signature

The verification of a Schnorr signature is simpler than that of an ECDSA

signature. Here are the steps to verify the signature (R_x, s) with the public key K_x and

the message m. First, we

verify that K_x is a valid

integer less than p. If this

is the case, we retrieve the corresponding point on the curve with K_y being even. We also extract R_x and s by splitting the

signature \text{SIG}. Then,

we check that R_x < p and s < n (the order of

the curve). Next, we calculate the challenge e in the same way as the issuer

of the signature:

e = \text{HASH}(\text{``BIP0340/challenge''}, R_x \Vert K_x \Vert m) \mod nThen, we calculate a reference point on the curve in this way:

R' = s \cdot G - e \cdot KFinally, we verify that R'_x = R_x. If the two x-coordinates match, then the signature (R_x, s) is indeed valid with the public key K_x.

Why does this work?

The signer has calculated s = r + e \cdot k \mod n, so R' = s \cdot G - e \cdot K should be equal to the original point R, because:

s \cdot G = (r + e \cdot k) \cdot G = r \cdot G + e \cdot k \cdot GSince K = k \cdot G, we have e \cdot k \cdot G = e \cdot K. Thus:

R' = r \cdot G = RTherefore, we have:

R'_x = R_xThe advantages of Schnorr signatures

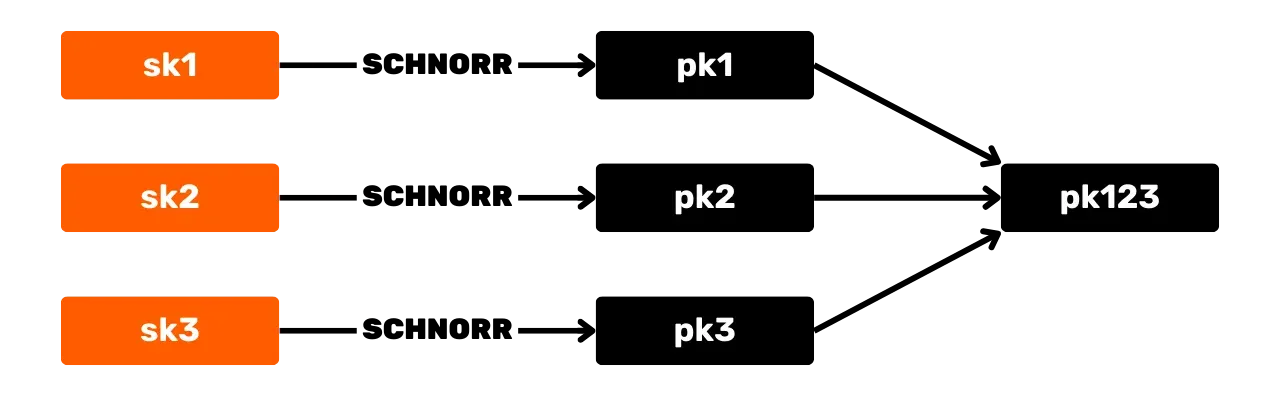

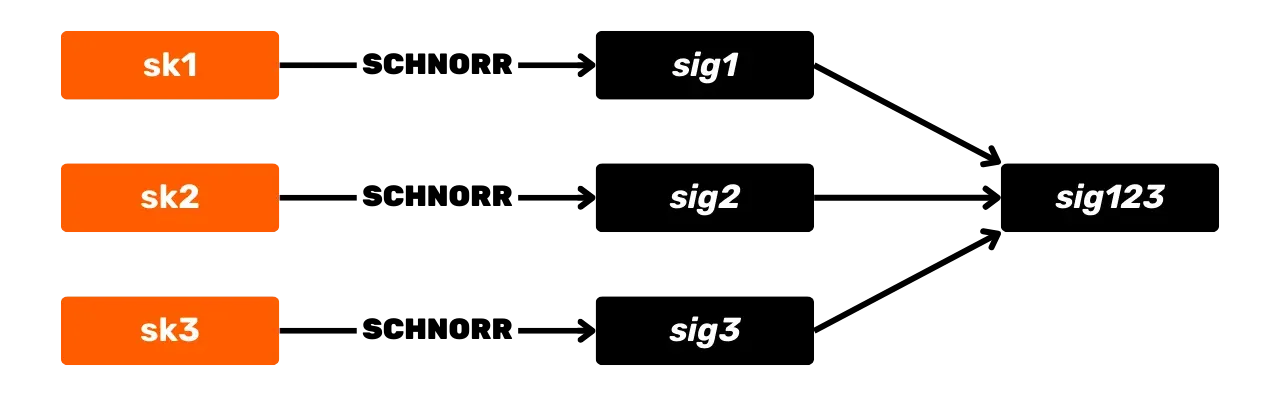

The Schnorr signature scheme offers several advantages for Bitcoin over the original ECDSA algorithm. First, Schnorr allows for the aggregation of keys and signatures. This means that multiple public keys can be combined into a single key.

And similarly, multiple signatures can be aggregated into a single valid signature. Thus, in the case of a multisignature transaction, a set of participants can sign with a single signature and a single aggregated public key. This significantly reduces storage and computation costs for the network, as each node only needs to verify a single signature.

Moreover, signature aggregation improves privacy. With Schnorr, it becomes impossible to distinguish a multisignature transaction from a standard single-signature transaction. This homogeneity makes chain analysis more difficult, as it limits the ability to identify wallet fingerprints.

Finally, Schnorr also offers the possibility of batch verification. By verifying multiple signatures simultaneously, nodes can gain efficiency, especially for blocks containing many transactions. This optimization reduces the time and resources needed to validate a block. Also, Schnorr signatures are not malleable, unlike signatures produced with ECDSA. This means that an attacker cannot modify a valid signature to create another valid signature for the same message and the same public key. This vulnerability was previously present in Bitcoin and notably prevented the secure implementation of the Lightning Network. It was resolved for ECDSA with the SegWit softfork in 2017, which involves moving the signatures to a separate database from the transactions to prevent their malleability.

Why did Satoshi choose ECDSA?

As we have seen, Satoshi initially chose to implement ECDSA for digital signatures in Bitcoin. Yet, we have also seen that Schnorr is superior to ECDSA in many aspects, and this protocol was created by Claus-Peter Schnorr in 1989, 20 years before the invention of Bitcoin.

Well, we don't really know why Satoshi didn't choose it, but a likely hypothesis is that this protocol was under patent until 2008. Although Bitcoin was created a year later, in January 2009, no open-source standardization for Schnorr signatures was available at that time. Perhaps Satoshi deemed it safer to use ECDSA, which was already widely used and tested in open-source software and had several recognized implementations (notably the OpenSSL library used until 2015 in Bitcoin Core, then replaced by libsecp256k1 in version 0.10.0). Or maybe he simply wasn't aware that this patent was going to expire in 2008. In any case, the most probable hypothesis seems related to this patent and the fact that ECDSA had a proven history and was easier to implement.

The sighash flags

As we have seen in previous chapters, digital signatures are often used to

unlock the script of an input. In the signing process, it is necessary to

include the signed data in the calculation, designated in our examples by

the message m. This data,

once signed, cannot be modified without rendering the signature invalid.

Indeed, whether for ECDSA or Schnorr, the signature verifier must include in

their calculation the same message m. If it differs from the

message m initially used by the

signer, the result will be incorrect and the signature will be deemed invalid.

It is then said that a signature covers certain data and protects it, in a way,

against unauthorized modifications.

What is a sighash flag?

In the specific case of Bitcoin, we've seen that the message m corresponds to the transaction. However, in reality, it's a bit more complex.

Indeed, thanks to sighash flags, it's possible to select specific data within

the transaction that will be covered or not by the signature. The "sighash flag"

is thus a parameter added to each input, allowing the determination of the components

of a transaction that are covered by the associated signature. These components

are the inputs and the outputs. The choice of the sighash flag thus determines

which inputs and which outputs of the transaction are fixed by the signature

and which can still be modified without invalidating it. This mechanism allows

signatures to commit transaction data according to the signer's intentions.

Obviously, once the transaction is confirmed on the blockchain, it becomes immutable, regardless of the sighash flags used. The possibility of modification via the sighash flags is limited to the period between the signing and the confirmation.

Generally, wallet software does not offer you the option to manually modify

the sighash flag of your inputs when you construct a transaction. By

default, SIGHASH_ALL is set. Personally, I only know of Sparrow

Wallet that allows this modification from the user interface.

What are the existing sighash flags in Bitcoin?

In Bitcoin, there are first and foremost 3 basic sighash flags:

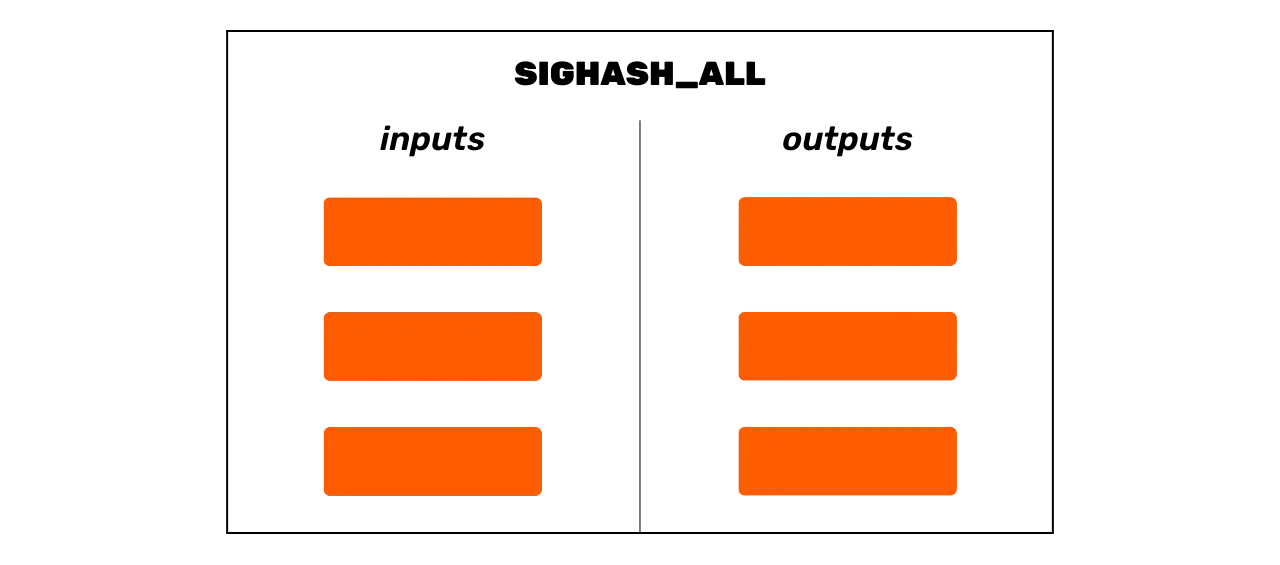

SIGHASH_ALL(0x01): The signature applies to all the inputs and all the outputs of the transaction. The transaction is thus entirely covered by the signature and can no longer be modified.SIGHASH_ALLis the most commonly used sighash in everyday transactions when one simply wants to make a transaction without it being able to be modified.

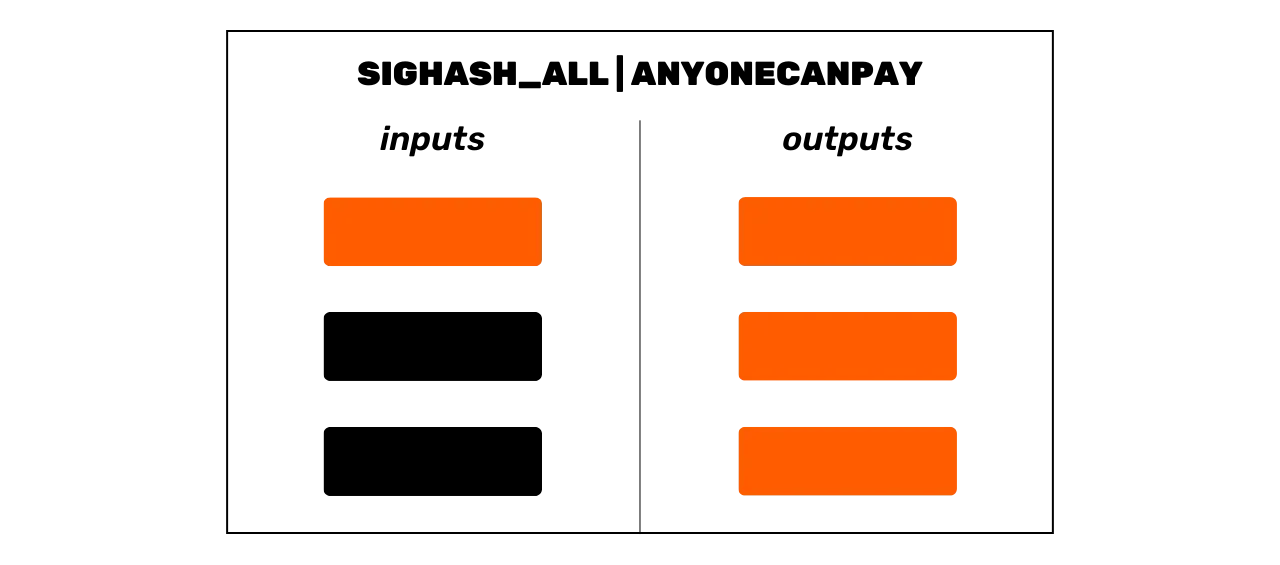

In all the diagrams of this chapter, the orange color represents the elements covered by the signature, while the black color indicates those that are not.

SIGHASH_NONE(0x02): The signature covers all the inputs but none of the outputs, thus allowing the modification of the outputs after the signature. In concrete terms, this is akin to a blank check. The signatory unlocks the UTXOs in inputs but leaves the field of outputs entirely modifiable. Anyone knowing this transaction can thus add the output of their choice, for example by specifying a receiving address to collect the funds consumed by the inputs, and then broadcast the transaction to recover the bitcoins. The signature of the owner of the inputs will not be invalidated, as it covers only the inputs.

SIGHASH_SINGLE(0x03): The signature covers all inputs as well as a single output, corresponding to the index of the signed input. For example, if the signature unlocks the scriptPubKey of input #0, then it also covers output #0. The signature also protects all other inputs, which can no longer be modified. However, anyone can add an additional output without invalidating the signature, provided that output #0, which is the only one covered by it, is not modified.

In addition to these three sighash flags, there is also the modifier SIGHASH_ANYONECANPAY (0x80). This modifier can be combined with a basic sighash flag

to create three new sighash flags:

SIGHASH_ALL | SIGHASH_ANYONECANPAY(0x81): The signature covers a single input while including all outputs of the transaction. This combined sighash flag allows, for example, the creation of a crowdfunding transaction. The organizer prepares the output with their address and the target amount, and each investor can then add inputs to fund this output. Once sufficient funds are gathered in inputs to satisfy the output, the transaction can be broadcast.

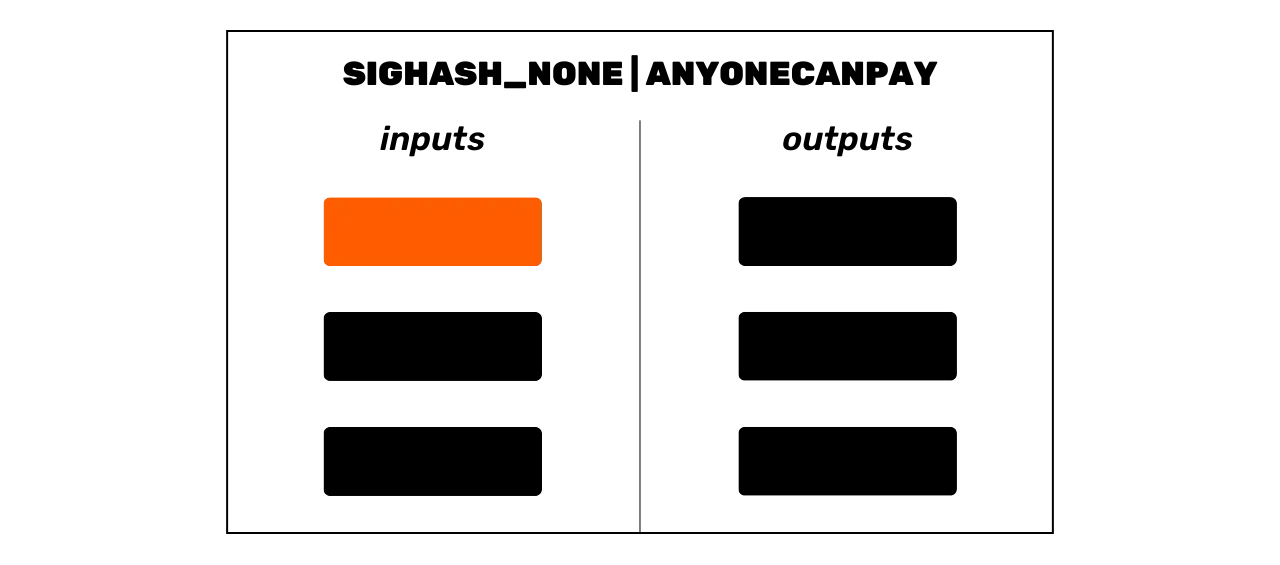

SIGHASH_NONE | SIGHASH_ANYONECANPAY(0x82): The signature covers a single input, without committing to any output;

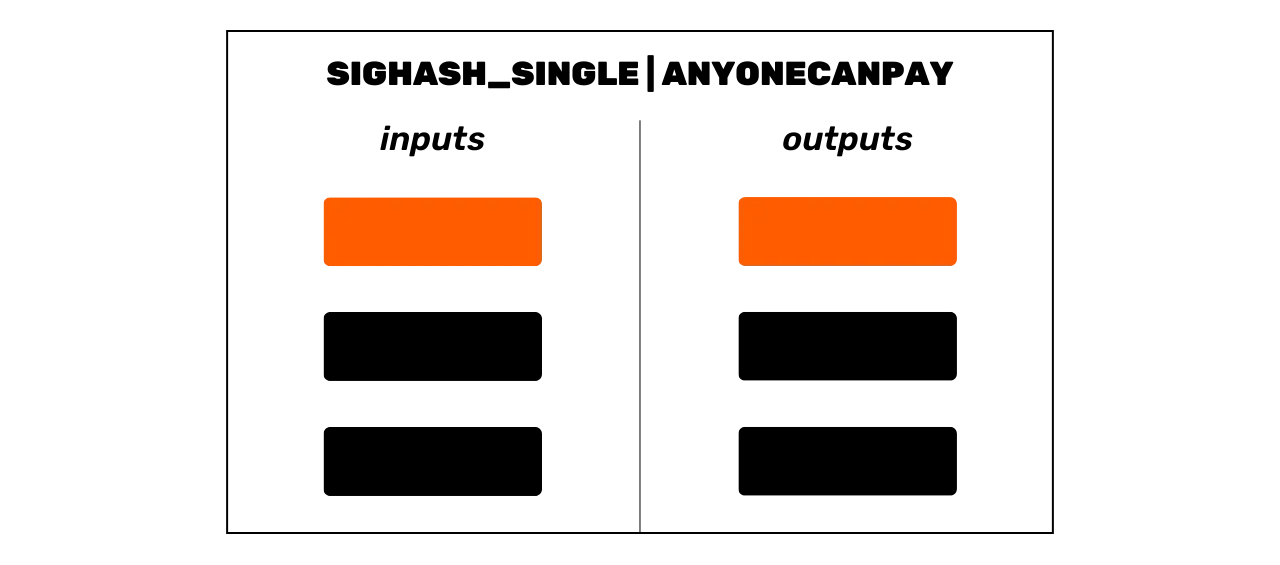

SIGHASH_SINGLE | SIGHASH_ANYONECANPAY(0x83): The signature covers a single input as well as the output having the same index as this input. For example, if the signature unlocks the scriptPubKey of input #3, it will also cover output #3. The rest of the transaction remains modifiable, both in terms of other inputs and other outputs.

Projects to Add New Sighash Flags

Currently (2024), only the sighash flags presented in the previous section

are usable in Bitcoin. However, some projects are considering the addition

of new sighash flags. For example, BIP118, proposed by Christian Decker and

Anthony Towns, introduces two new sighash flags: SIGHASH_ANYPREVOUT and SIGHASH_ANYPREVOUTANYSCRIPT (AnyPrevOut = "Any Previous Output").

These two sighash flags would offer an additional possibility in Bitcoin: creating signatures that do not cover any specific input of the transaction.

This idea was initially formulated by Joseph Poon and Thaddeus Dryja in the

Lightning White Paper. Before its renaming, this sighash flag was named SIGHASH_NOINPUT. If this sighash flag is integrated into Bitcoin, it will enable the use

of covenants, but it is also a mandatory prerequisite for implementing

Eltoo, a general protocol for second layers that defines how to jointly

manage the ownership of a UTXO. Eltoo was specifically designed to solve the

problems associated with the mechanisms for negotiating the state of

Lightning channels, that is, between opening and closing.

To deepen your knowledge of the Lightning Network, after the CYP201 course, I highly recommend the LNP201 course by Fanis Michalakis, which covers the topic in detail:

https://planb.network/courses/34bd43ef-6683-4a5c-b239-7cb1e40a4aeb

In the next part, I propose to discover how the mnemonic phrase at the base of your Bitcoin wallet works.

The mnemonic phrase

Evolution of Bitcoin wallets

Now that we have explored the workings of hash functions and digital signatures, we can study how Bitcoin wallets function. The goal will be to describe how a wallet in Bitcoin is constructed, how it is decomposed, and what the different pieces of information that constitute it are used for. This understanding of the wallet mechanisms will allow you to improve your use of Bitcoin in terms of security and privacy.

Before diving into the technical details, it is essential to clarify what is meant by "Bitcoin wallet" and to understand its utility.

What is a Bitcoin wallet?

Unlike traditional wallets, which allow you to store physical bills and coins, a Bitcoin wallet does not "contain" bitcoins per se. Indeed, bitcoins do not exist in a physical or digital form that can be stored, but are represented by units of account depicted in the Bitcoin system in the form of UTXOs (Unspent Transaction Outputs).

UTXOs thus represent fragments of bitcoins, of varying sizes, that can be spent provided that their scriptPubKey is satisfied. To spend his bitcoins, a user must provide a scriptSig that unlocks the scriptPubKey associated with his UTXO. This proof is generally made through a digital signature, generated from the private key corresponding to the public key present in the scriptPubKey. Thus, the crucial element that the user must secure is the private key. The role of a Bitcoin wallet is precisely to manage these private keys securely. In reality, its role is more akin to that of a keychain than a wallet in the traditional sense.

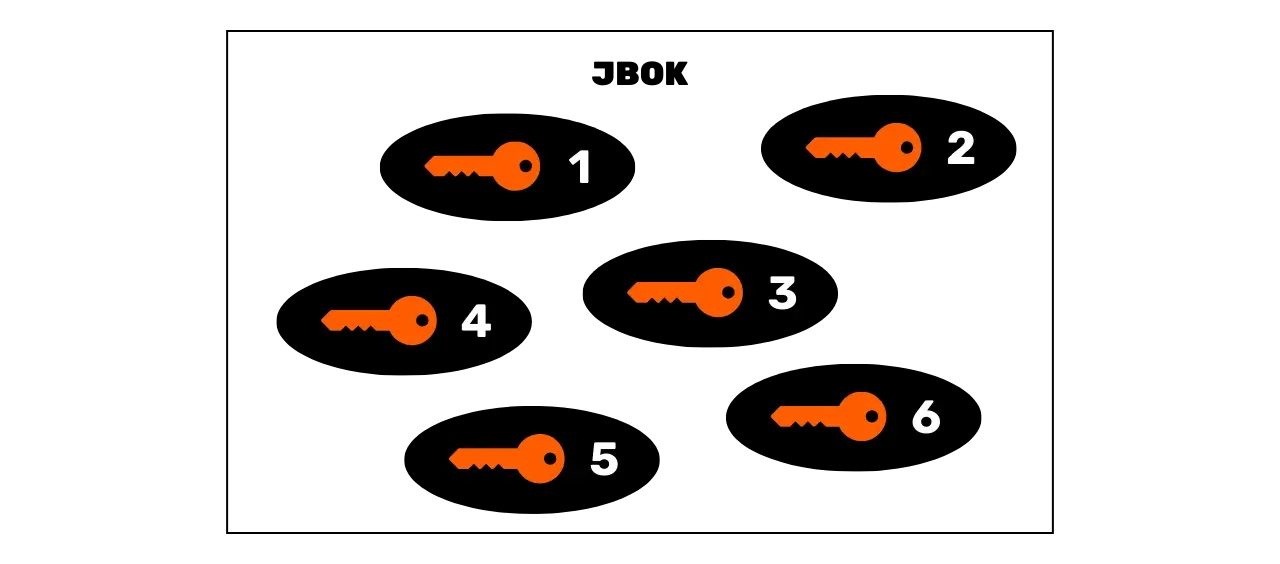

JBOK Wallets

The first wallets used in Bitcoin were JBOK (Just a Bunch Of Keys) wallets, which grouped together private keys generated independently and without any link between them. These wallets operated on a simple model where each private key could unlock a unique Bitcoin receiving address.

If one wished to use multiple private keys, it was then necessary to make as many backups to ensure access to funds in case of problems with the device hosting the wallet. If using a single private key, this wallet structure may suffice, since a single backup is enough. However, this poses a problem: in Bitcoin, it is strongly advised against using always the same private key. Indeed, a private key is associated with a unique address, and Bitcoin receiving addresses are normally designed for one-time use. Each time you receive funds, you should generate a new blank address.

This constraint stems from Bitcoin's privacy model. By reusing the same address, it makes it easier for external observers to trace Bitcoin transactions. That's why reusing a receiving address is strongly discouraged. However, to have multiple addresses and publicly separate our transactions, it is necessary to manage multiple private keys. In the case of JBOK wallets, this implies creating as many backups as there are new pairs of keys, a task that can quickly become complex and difficult to maintain for users.

To learn more about Bitcoin's privacy model and discover methods to protect your privacy, I also recommend following my BTC204 course on Plan ₿ Network:

https://planb.network/courses/65c138b0-4161-4958-bbe3-c12916bc959c

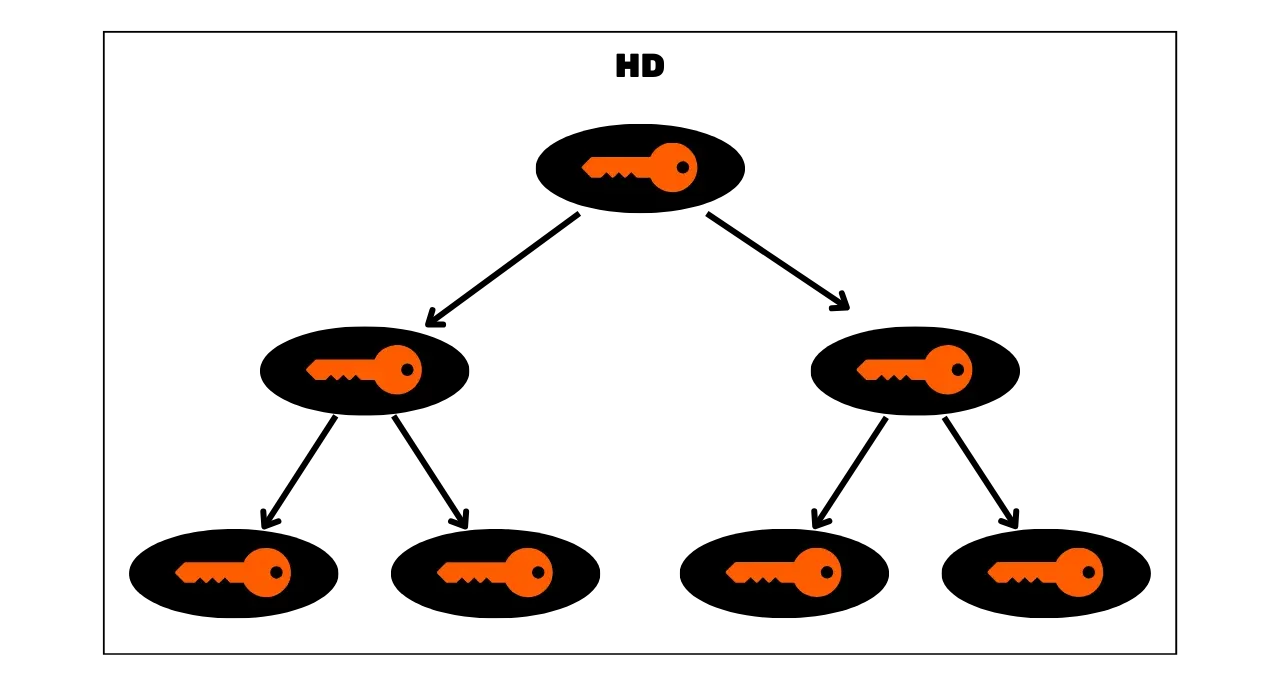

HD Wallets

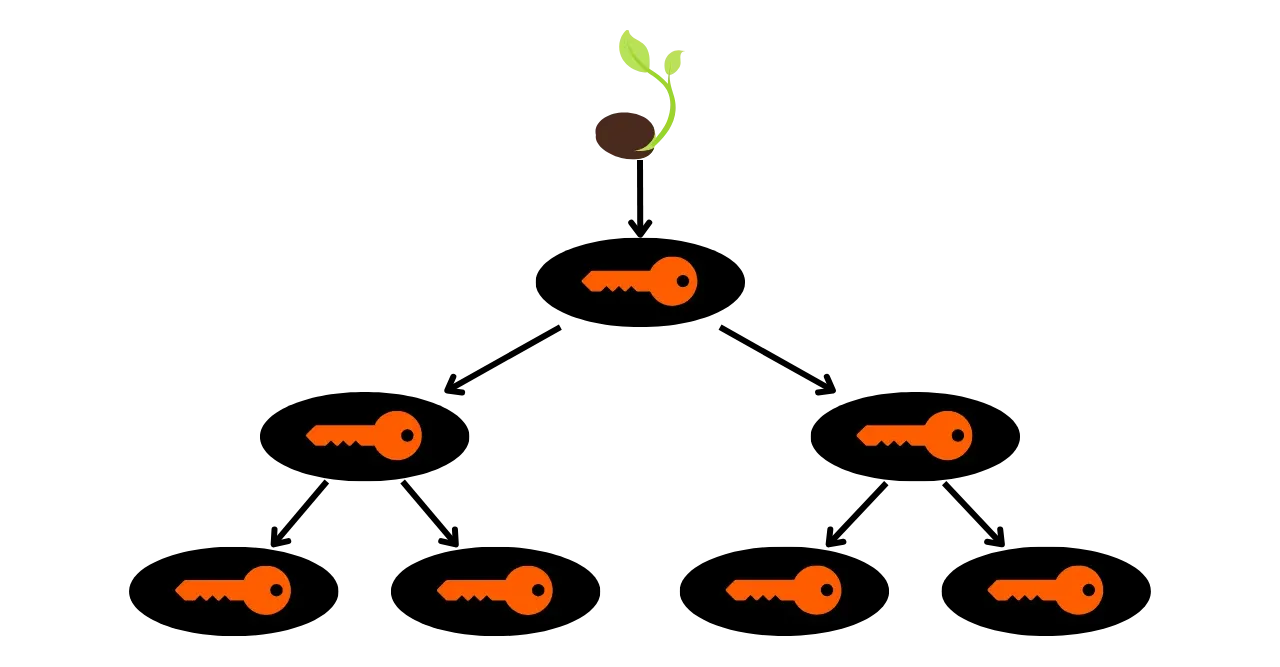

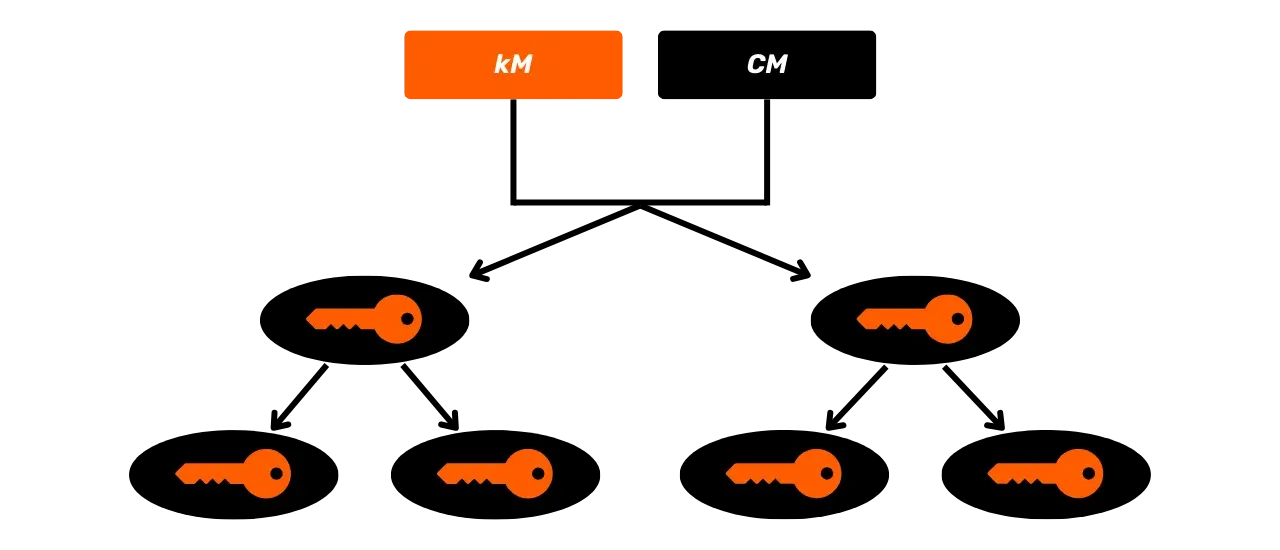

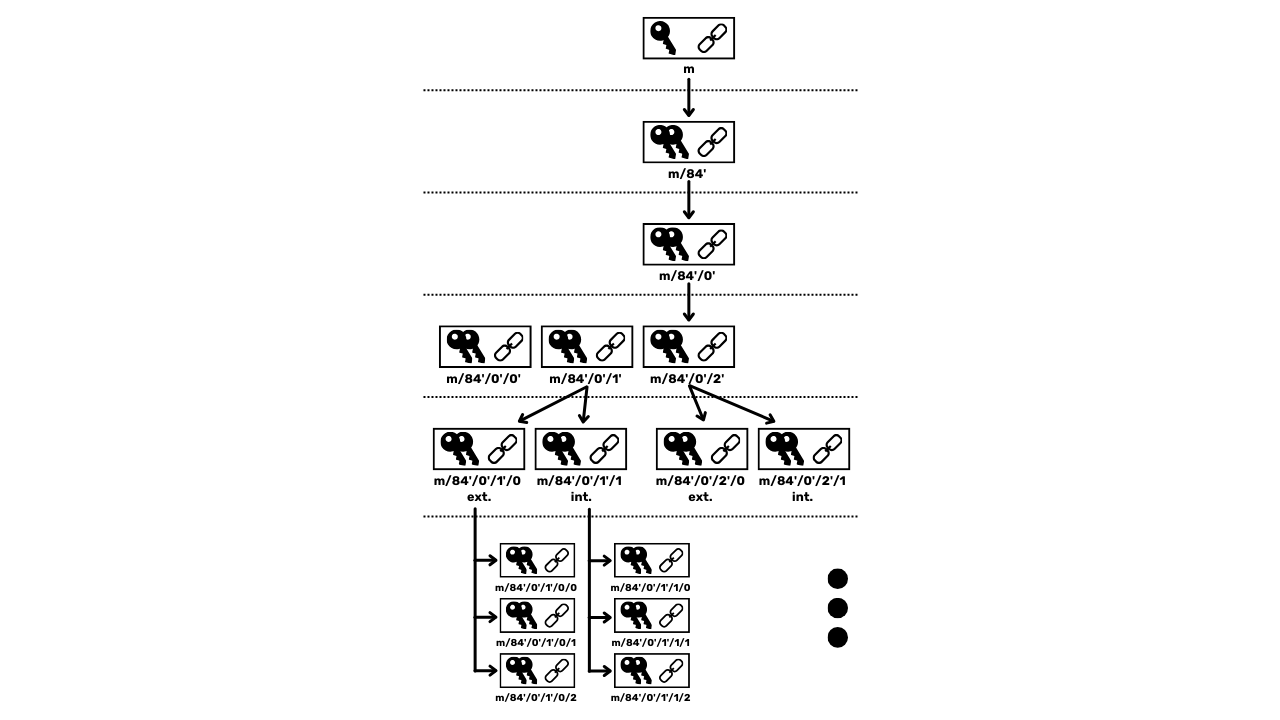

To address the limitation of JBOK wallets, a new wallet structure was subsequently utilized. In 2012, Pieter Wuille proposed an improvement with BIP32, which introduces HD (Hierarchical Deterministic) wallets. The principle of an HD wallet is to derive all private keys from a single source of information, called a seed, in a deterministic and hierarchical manner. This seed is generated randomly when the wallet is created and constitutes a unique backup that allows for the recreation of all the wallet's private keys. Thus, the user can generate a very large number of private keys to avoid address reuse and preserve their privacy, while only needing to make a single backup of their wallet via the seed.

In HD wallets, key derivation is performed according to a hierarchical structure that allows keys to be organized into derivation subspaces, each subspace being further subdividable, to facilitate fund management and interoperability between different wallet software. Nowadays, this standard is adopted by the vast majority of Bitcoin users. For this reason, we will examine it in detail in the following chapters.

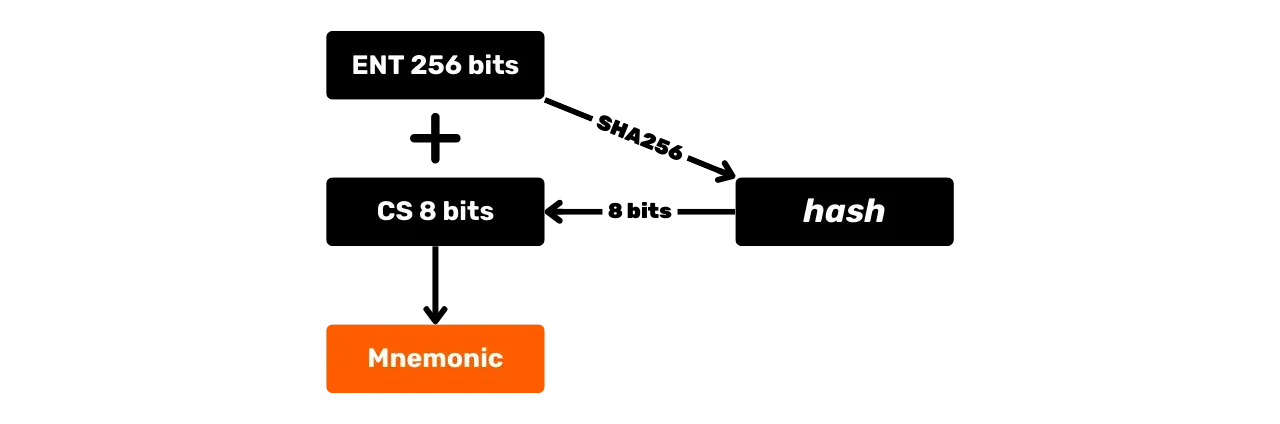

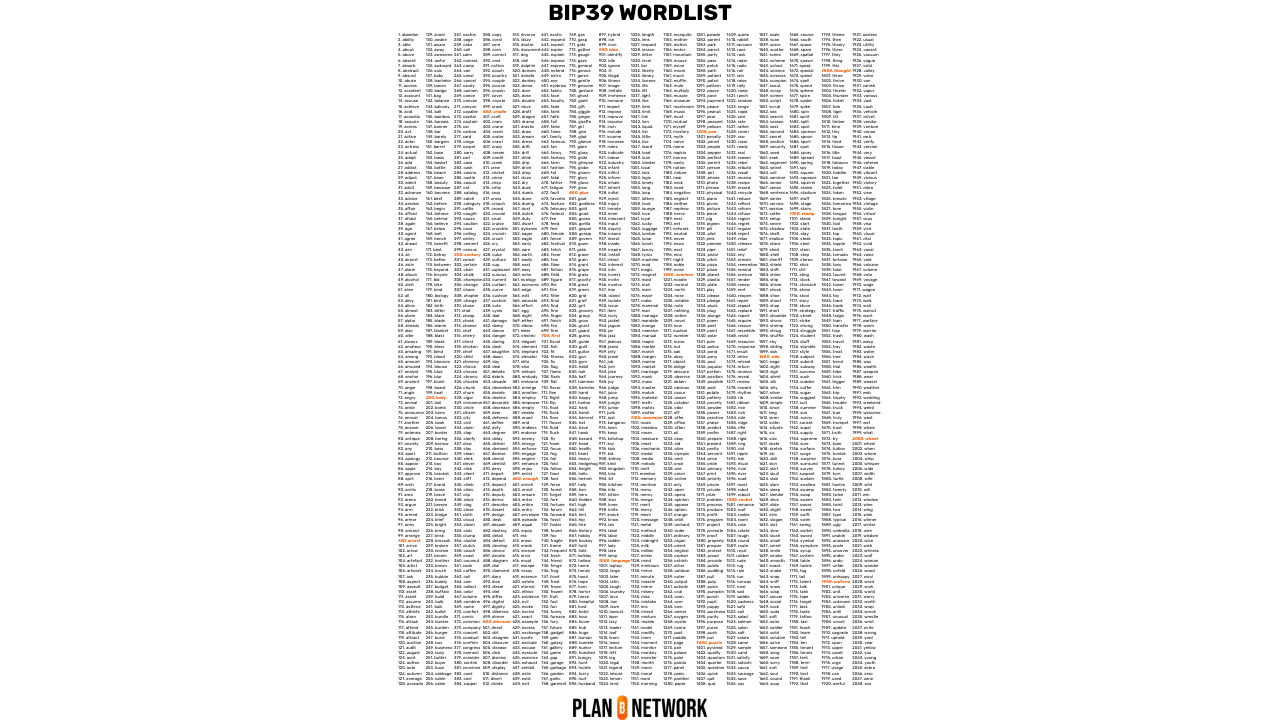

The BIP39 Standard: The Mnemonic Phrase

In addition to BIP32, BIP39 standardizes the seed format as a mnemonic phrase, to facilitate backup and readability by users. The mnemonic phrase, also called a recovery phrase or 24-word phrase, is a sequence of words drawn from a predefined list that securely encodes the wallet's seed.

The mnemonic phrase greatly simplifies backup for the user. In case of loss, damage, or theft of the device hosting the wallet, simply knowing this mnemonic phrase allows for the recreation of the wallet and recovery of access to all the funds secured by it.

In the upcoming chapters, we will explore the internal workings of HD wallets, including key derivation mechanisms and the different possible hierarchical structures. This will allow you to better understand the cryptographic foundations upon which the security of funds in Bitcoin is based. And to start, in the next chapter, I propose we discover the role of entropy at the base of your wallet.

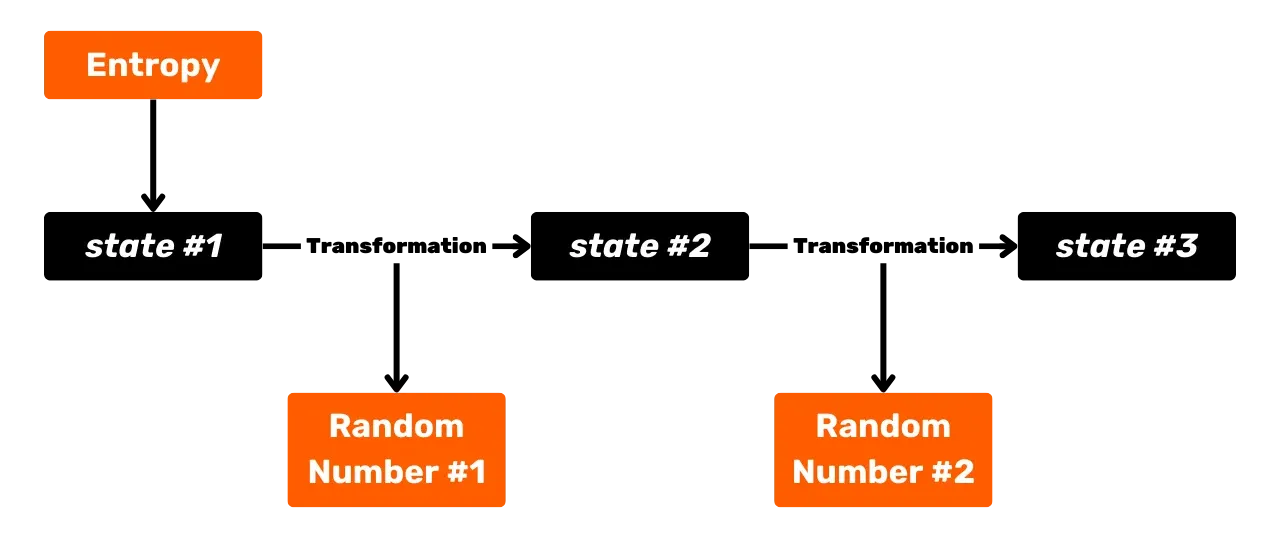

Entropy and Random Numbers

b43c715d-affb-56d8-a697-ad5bc2fffd63 Modern HD wallets rely on a single initial piece of information called "entropy" to deterministically generate the entire set of wallet keys. This entropy is a pseudo-random number that partly determines the security of the wallet.

Definition of Entropy

Entropy, in the context of cryptography and information, is a quantitative measure of the uncertainty or unpredictability associated with a data source or a random process. It plays an important role in the security of cryptographic systems, especially in the generation of keys and random numbers. High entropy ensures that the generated keys are sufficiently unpredictable and resistant to brute force attacks, where an attacker tries all possible combinations to guess the key.

In the context of Bitcoin, entropy is used to generate the seed. When creating an HD wallet, the construction of the mnemonic phrase is done from a random number, itself derived from a source of entropy. The phrase is then used to generate multiple private keys, in a deterministic and hierarchical manner, to create spending conditions on UTXOs.

Methods of Generating Entropy

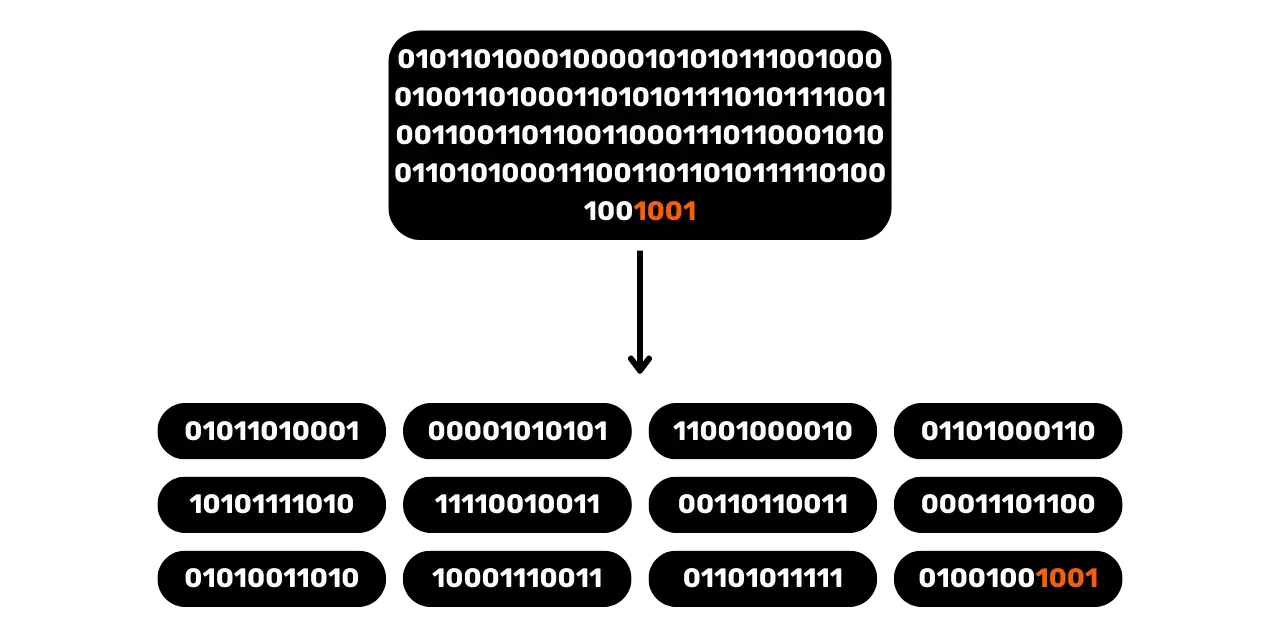

The initial entropy used for an HD wallet is generally 128 bits or 256 bits, where:

- 128 bits of entropy correspond to a mnemonic phrase of 12 words;

- 256 bits of entropy correspond to a mnemonic phrase of 24 words.

In most cases, this random number is generated automatically by the wallet software using a PRNG (Pseudo-Random Number Generator). PRNGs are a category of algorithms used to generate sequences of numbers from an initial state, which have characteristics approaching that of a random number, without actually being one. A good PRNG must have properties such as output uniformity, unpredictability, and resistance to predictive attacks. Unlike true random number generators (TRNGs), PRNGs are deterministic and reproducible.

An alternative is to manually generate the entropy, which offers better control but is also much riskier. I strongly advise against generating the entropy for your HD wallet yourself.

In the next chapter, we will see how we go from a random number to a mnemonic phrase of 12 or 24 words.

The Mnemonic Phrase