name: The RGB protocol, from theory to practice goal: Acquire the skills needed to understand and use RGB objectives:

- Understand the fundamental concepts of the RGB protocol

- Master the principles of client-side validation and Bitcoin commitments

- Learn how to create, manage and transfer RGB contracts

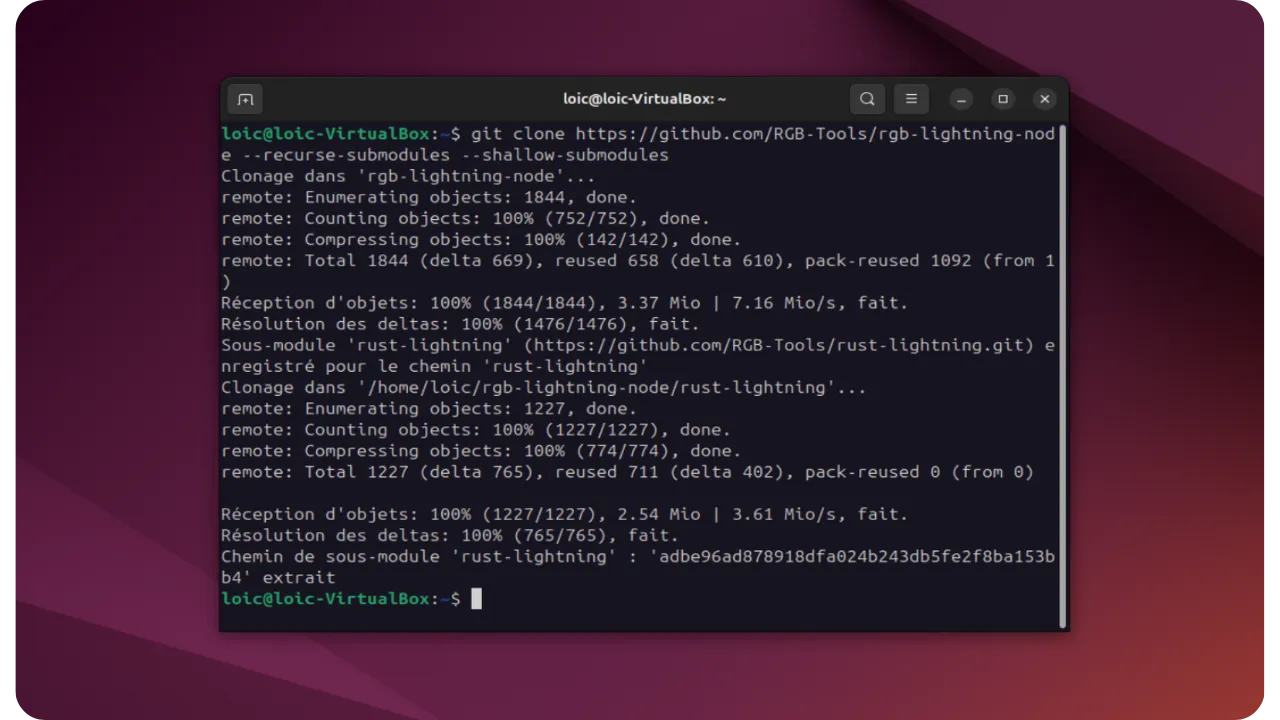

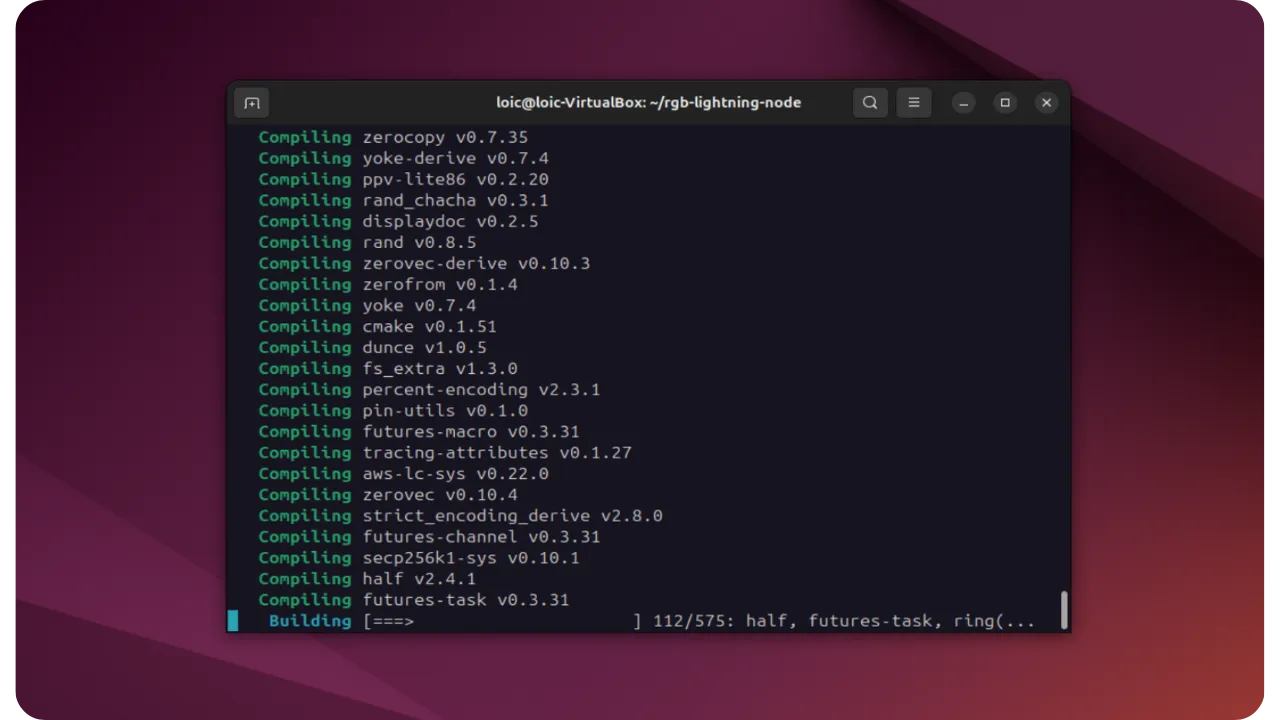

- How to operate an RGB-compatible Lightning node

Discovering the RGB protocol

Dive into the world of RGB, a protocol designed to implement and enforce digital rights, in the form of contracts and assets, based on the consensus rules and operations of the Bitcoin blockchain. This comprehensive training course guides you through the technical and practical foundations of RGB, from the concepts of "Client-side Validation" and "Single-use Seals", to the implementation of advanced smart contracts.

Through a structured, step-by-step program, you'll discover the mechanisms of client-side validation, deterministic commitments on Bitcoin and interaction patterns between users. Learn how to create, manage and transfer RGB tokens on Bitcoin or the Lightning Network.

Whether you're a developer, Bitcoin enthusiast, or simply curious to learn more about this technology, this training course will provide you with the tools and knowledge you need to master RGB and build innovative solutions on Bitcoin.

The course is based on a live seminar organized by Fulgur'Ventures and taught by three renowned teachers and RGB experts.

Introduction

Course presentation

Hello everyone, and welcome to this training course dedicated to RGB, a client-side validated smart contract system running on Bitcoin and the Lightning Network. The structure of this course is designed to enable in-depth exploration of this complex subject. Here's how the course is organized:

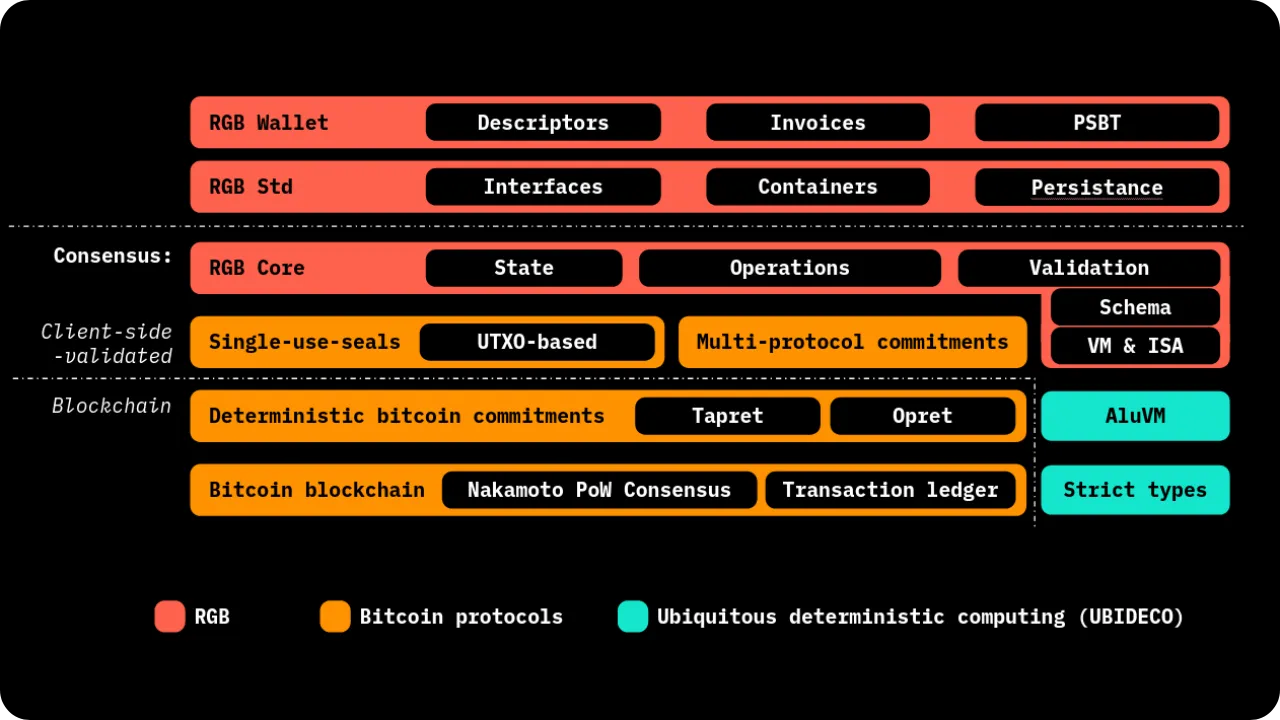

Section 1: Theory

The first section is dedicated to the theoretical concepts needed to understand the fundamentals of client-side validation and RGB. As you'll discover in this course, RGB introduces a host of technical concepts not usually seen in Bitcoin. In this section, you'll also find a glossary providing definitions for all terms specific to the RGB protocol.

Section 2: Practice

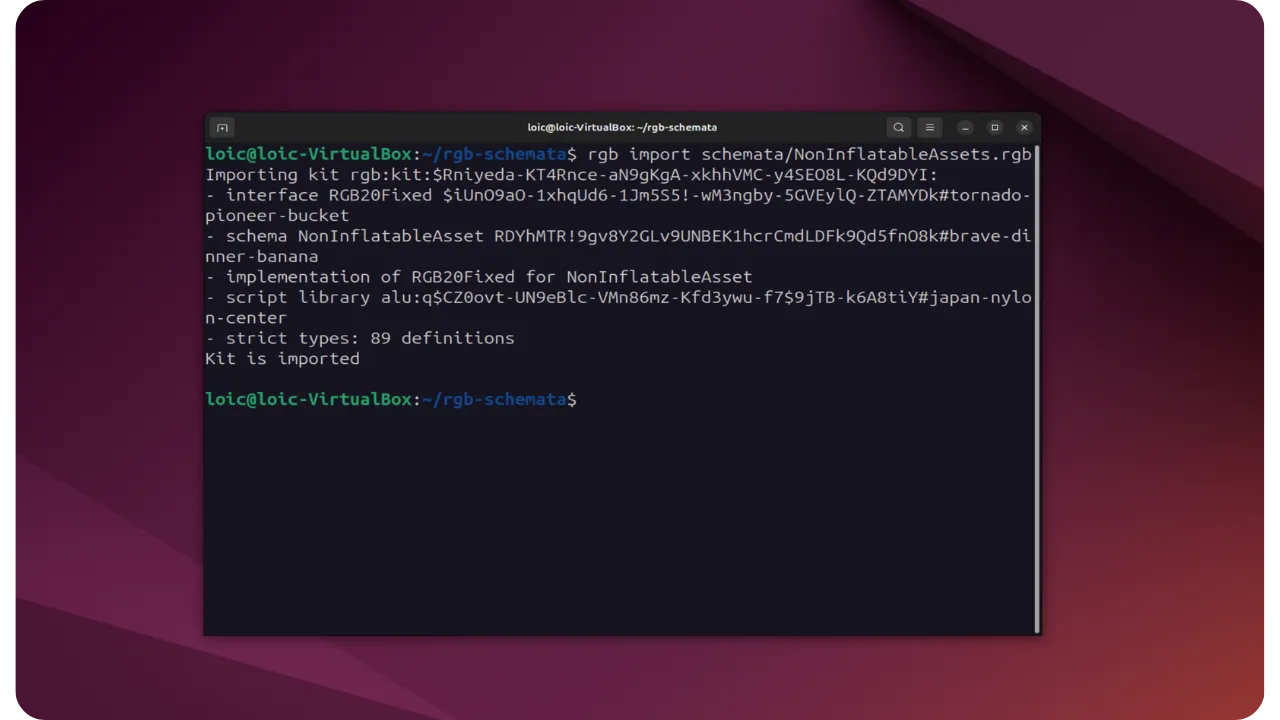

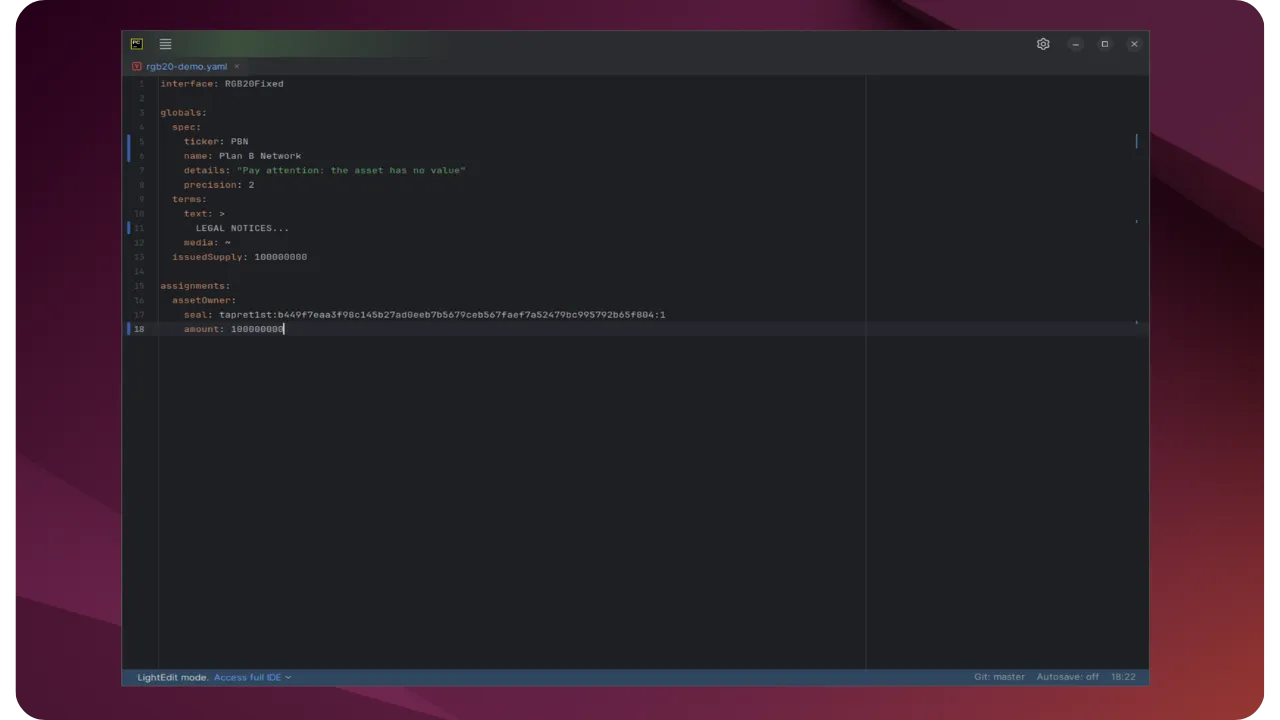

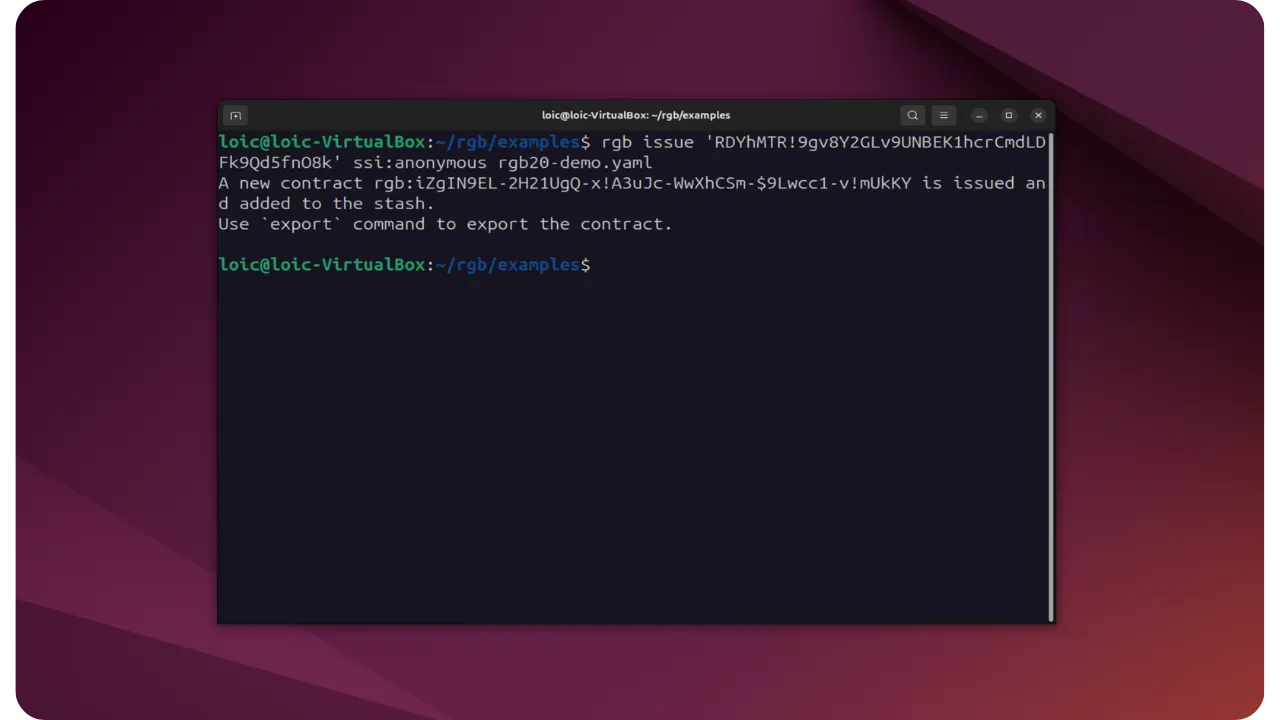

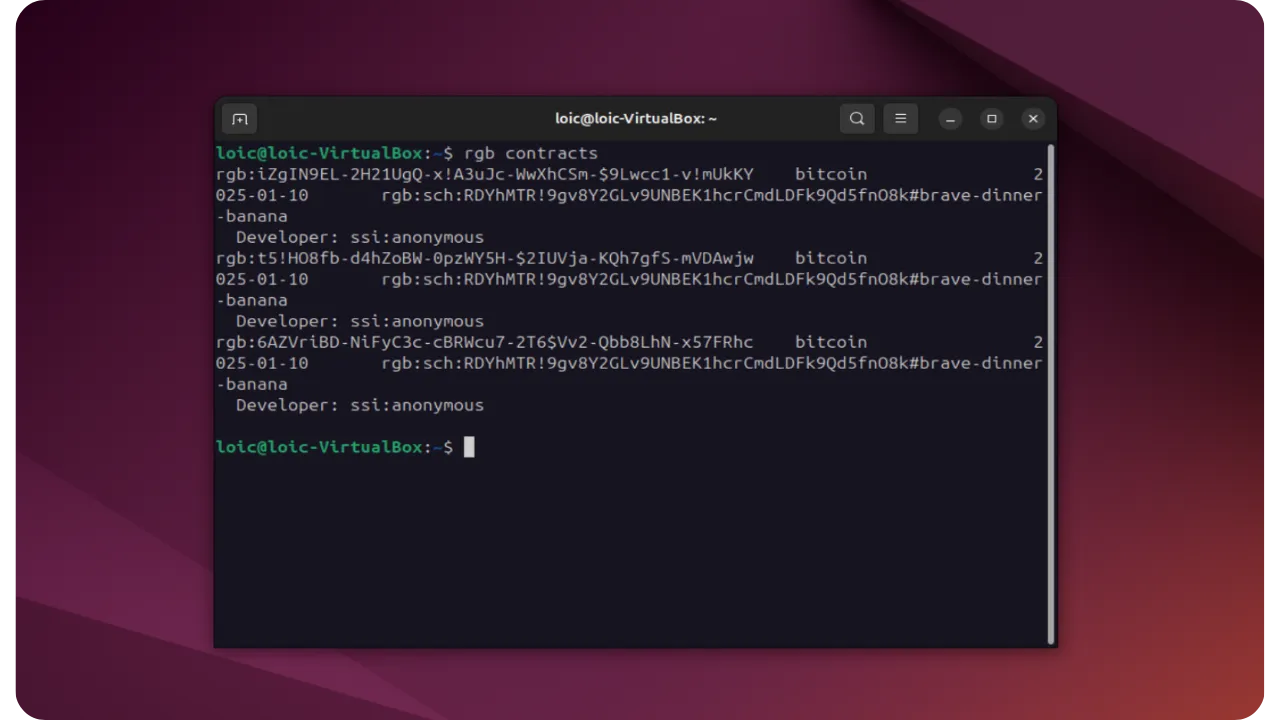

The second section will focus on the application of the theoretical concepts seen in section 1. We'll learn how to create and manipulate RGB contracts. We'll also see how to program with these tools. These first two sections are presented by Maxim Orlovsky.

Section 3: Applications

The final section is led by other speakers who present concrete RGB-based applications, to highlight real-life use cases.

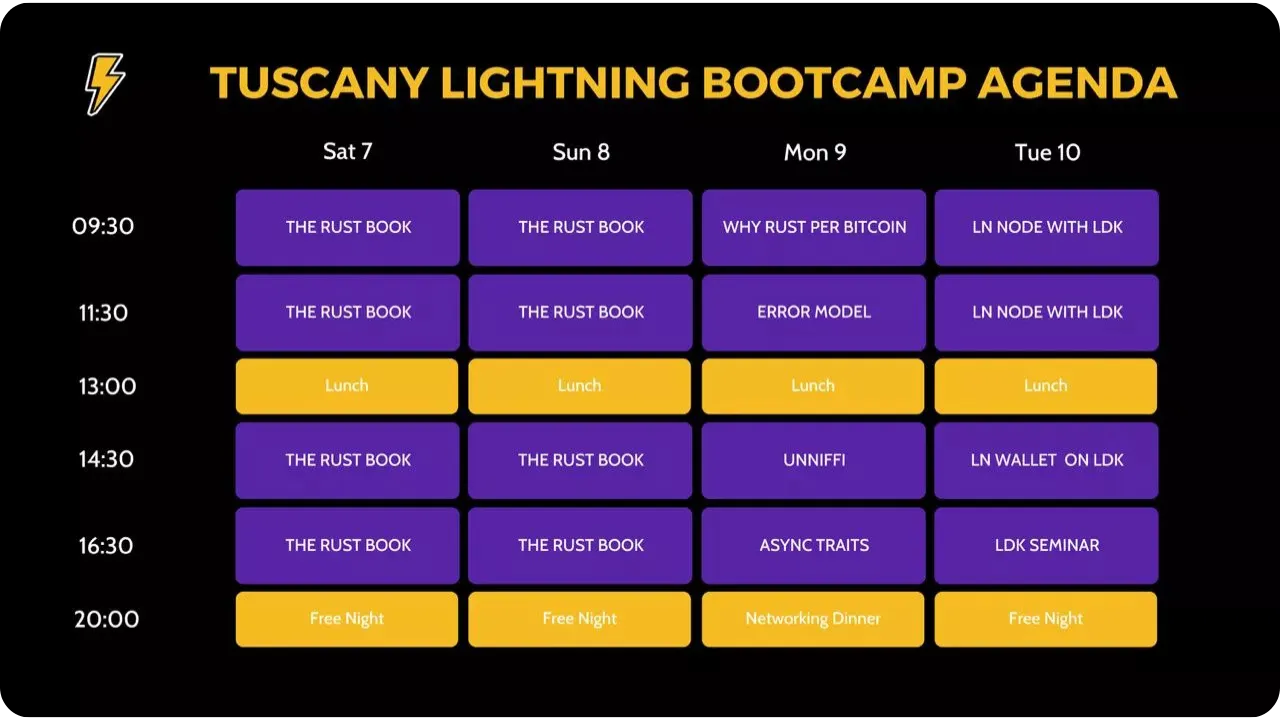

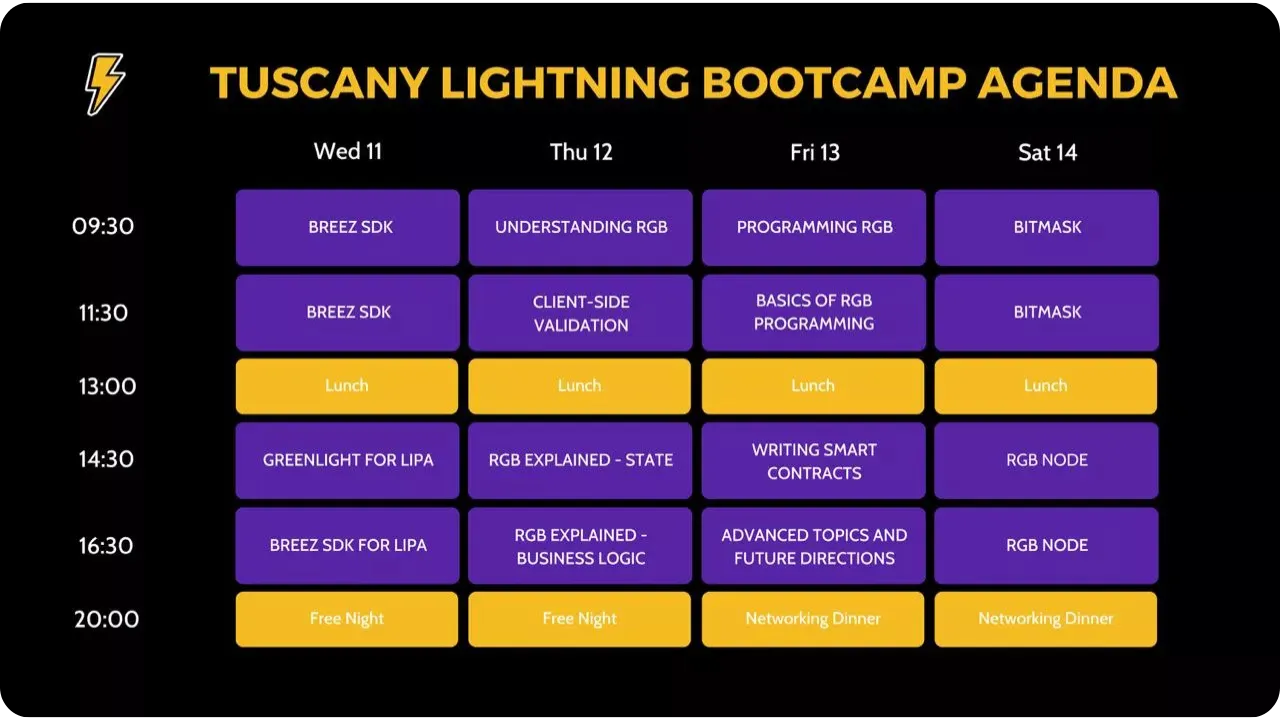

This training course originally grew out of a two-week advanced development bootcamp in Viareggio, Tuscany, organized by Fulgur'Ventures. The first week, focused on Rust and SDKs, can be found in this other course:

https://planb.network/courses/9fbd8b57-f278-4304-8d88-a2d384eaff58

In this course, we focus on the second week of the bootcamp, which focuses on RGB.

Week 1 - LNP402:

Week 2 - Current training CSV402:

Many thanks to the organizers of these live courses and to the 3 teachers who took part:

- Maxim Orlovsky: Ex Tenebrae sententia sapiens dominabitur astris. Cypher, AI, robotics, transhumanism. Creator of RGB, Prime, Radiant and lnp_bp, mycitadel_io & cyphernet_io;

- Hunter Trujilo: Developer, Rust, Bitcoin, Lightning, RGB;

- Federico Tenga: I'm doing my bit to turn the world into a cypherpunk dystopia. Currently working on RGB at Bitfinex.

The written version of this training course was drafted using 2 main resources:

- Videos of Maxim Orlovsky, Hunter Trujilo and Frederico Tenga's seminar at Lightning Bootcamp;

- The RGB documentation, the production of which was sponsored by Bitfinex.

Ready to dive into the complex and fascinating world of RGB? Let's go!

RGB in theory

Introduction to distributed computing concepts

RGB is a protocol designed to apply and enforce digital rights (in the form of contracts and assets) in a scalable and confidential way, based on the consensus rules and operations of the Bitcoin blockchain. The aim of this first chapter is to present the basic concepts and terminology around the RGB protocol, highlighting in particular its close links with basic distributed computing concepts such as Client-side Validation and Single-use Seals.

In this chapter, we explore the fundamentals of distributed consensus systems and see how RGB fits into this family of technologies. We'll also introduce the main principles that help us understand why RGB aims to be extensible and independent of Bitcoin's own consensus mechanism, while relying on it when necessary.

Introduction

Distributed computing, a specific branch of computer science, studies the protocols used to circulate and process information on a network of nodes. Together, these nodes and the protocol rules constitute what is known as a distributed system. Among the essential properties that characterize such a system , some are:

- The capability of independent verification and validation of certain data by each node;

- The possibility for nodes to construct (depending on the protocol) a complete or partial view of the information. These views are the states of the distributed system;

- The chronological order of operations, so that data is reliably time-stamped and there is a consensus on the sequence of events (sequence of states).

In particular, the notion of consensus in a distributed system covers two aspects:

- Recognition of the validity of state changes (according to protocol rules);

- The agreement on the order of these state changes, which makes it impossible to rewrite or reverse validated operations a posteriori (this is also known in Bitcoin as "double-spend protection").

The first functional, permission-free implementation of a distributed consensus mechanism was introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto with Bitcoin, thanks to the combined use of a blockchain data structure and a Proof-of-Work (PoW) algorithm. In this system, the credibility of the block history depends on the computing power devoted to it by the nodes (miners). Bitcoin is therefore a major and historic example of a distributed consensus system open to all (permissionless).

In the world of blockchain and distributed computing, we can distinguish two fundamental paradigms: blockchain in the traditional sense, and state channels, the best example of which in production is the Lightning Network. The blockchain is defined as a register of chronologically ordered events, replicated by consensus within an open, permission-free network. State channels, on the other hand, are peer-to-peer channels that enable two (or more) participants to maintain an updated state off-chain, using the blockchain only when opening and closing these channels.

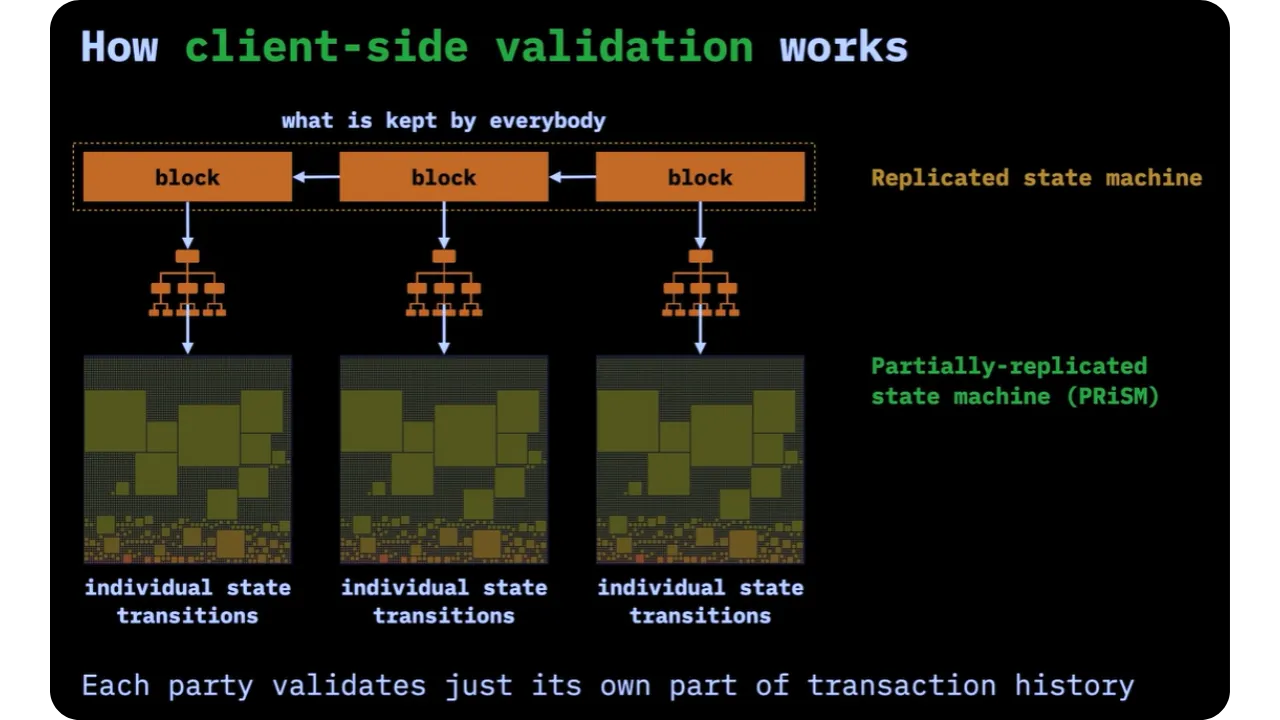

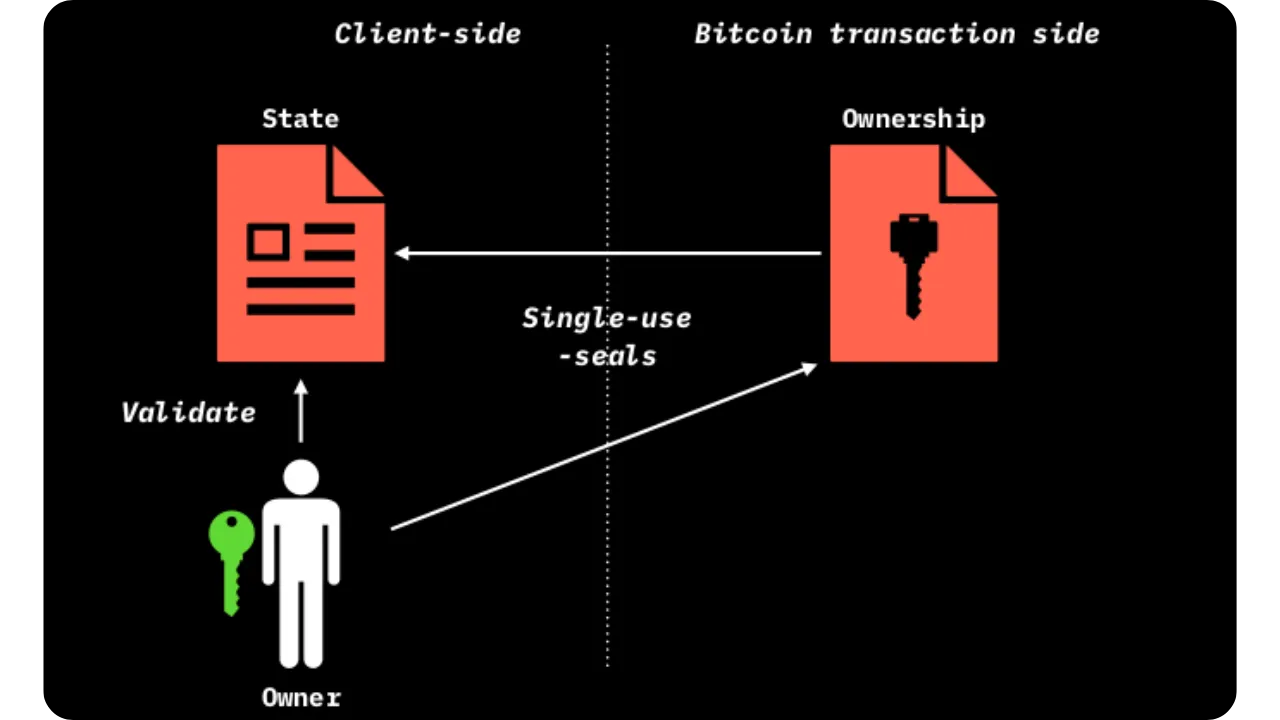

In the context of Bitcoin, you're no doubt familiar with the principles of mining, decentralization and finality of transactions on the blockchain, as well as how payment channels work. With RGB, we're introducing a new paradigm called Client-side Validation, which, unlike blockchain or Lightning, consists in locally (client-side) storing and validating the state transitions of a smart contract. This also differs from other "DeFi" techniques (rollups, plasma, ARK, etc.), where the Client-side Validation relies on the blockchain to prevent double-spending and to have a time-stamping system, while keeping the register of off-chain states and transitions, only with the participants concerned.

Later on, we'll also introduce an important term: the notion of "stash", which refers to the set of client-side data required to preserve the state of a contract, as this data is not replicated globally across the network. Finally, we'll look at the rationale behind RGB, a protocol that takes advantage of Client-side Validation, and why it complements existing approaches (blockchain and state channels).

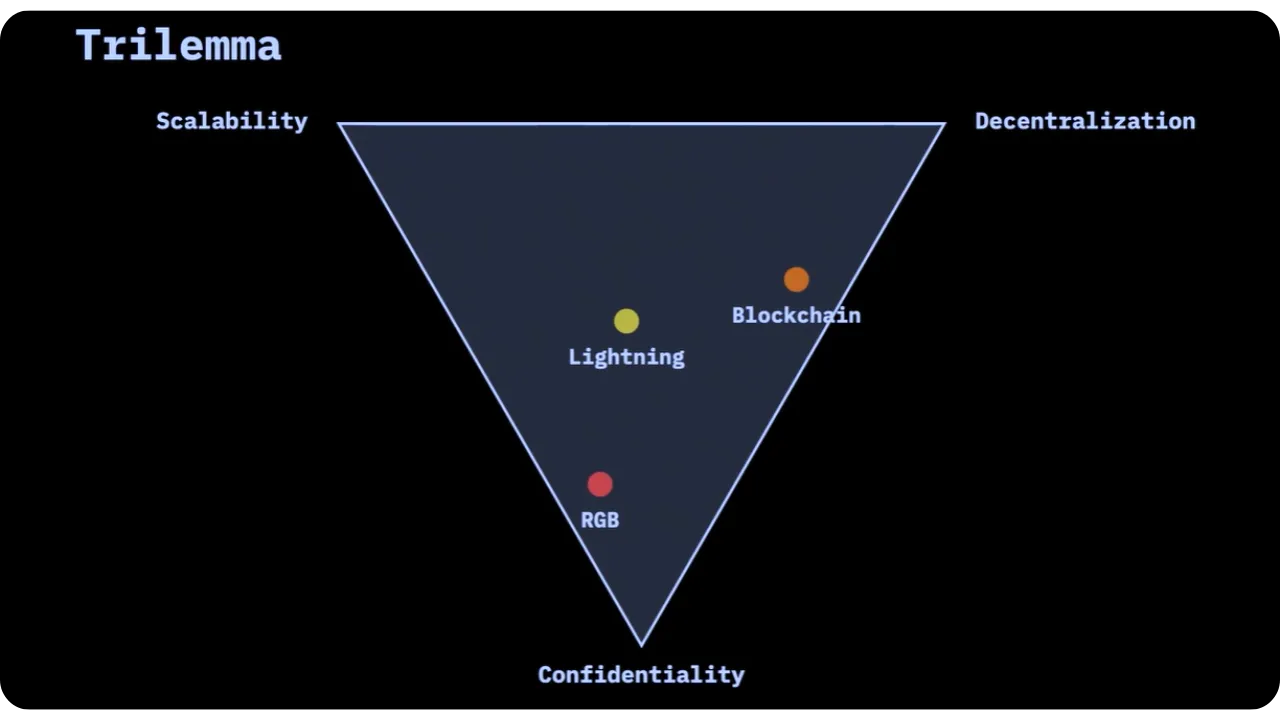

Trilemmas in distributed computing

To understand how Client-side Validation and RGB address problems not solved by blockchain and Lightning, let's discover 3 major "trilemmas" in distributed computing:

- Scalability, Decentralization, Privacy;

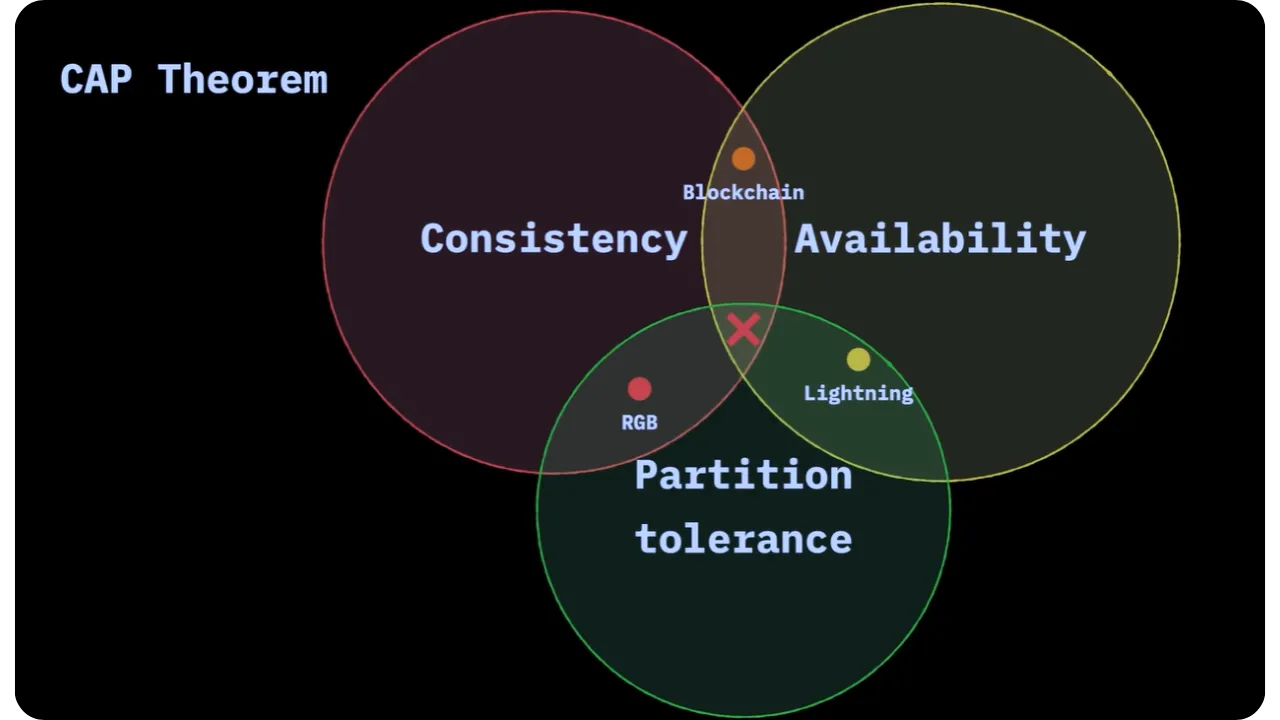

- CAP Theorem (Consistency, Availability, Partition Tolerance);

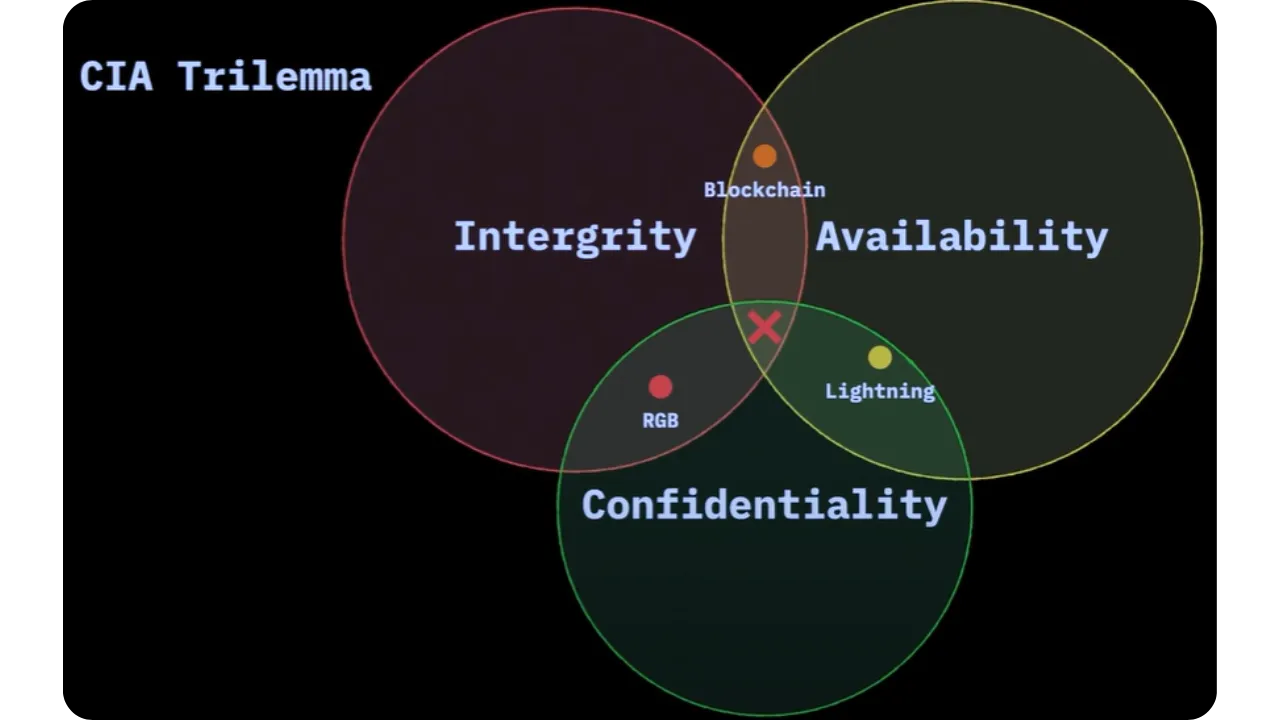

- CIA trilemma (Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability).

1. Scalability, decentralization and confidentiality

- Blockchain (Bitcoin)

Blockchain is highly decentralized, but not very scalable. What's more, since everything is in a global, public register, confidentiality is limited. We can try to improve confidentiality with zero-knowledge technologies (confidential transactions, mimblewimble schemes, etc.), but the public chain cannot hide the transaction graph.

- Lightning/State channels

State channels (as with the Lightning Network) are more scalable and more private than blockchain, as transactions take place off-chain. However, the obligation to publicly announce certain elements (funding transactions, network topology) and the monitoring of network traffic can partly compromise confidentiality. Decentralization also suffers: routing is cash-intensive, and major nodes can become centralization points. This is precisely the phenomenon we're beginning to see on Lightning.

- Client-side Validation (RGB)

This new paradigm is even more scalable and more confidential, because not only can we integrate zero-disclosure proof-of-knowledge techniques, but there is no global graph of transactions, since nobody holds the entire register. On the other hand, it also implies a certain compromise on decentralization: the issuer of a smart contract can have a central role (like a "contract deployer" in Ethereum). However, unlike blockchain, with Client-side Validation, you only store and validate the contracts you're interested in, which improves scalability by avoiding the need to download and verify all existing states.

2. CAP Theorem (Consistency, Availability, Partition tolerance)

The CAP theorem emphasizes that it is impossible for a distributed system to simultaneously satisfy Consistency,Availability and Partition tolerance.

- Blockchain

The blockchain favors consistency and availability, but doesn't do well with network partitioning: if you can't see a block, you can't act and have the same view as the whole network.

- Lightning

A system of state channels has availability and partitioning tolerance (since two nodes can remain connected to each other even if the network is fragmented), but overall consistency depends on the opening and closing of channels on the blockchain.

- Client-side Validation (RGB)

A system like RGB offers consistency (each participant validates its data locally, without ambiguity) and partitioning tolerance (you keep your data autonomously), but does not guarantee global availability (everyone has to make sure they have the relevant pieces of history, and some participants may not publish anything or stop sharing certain information).

3. CIA trilemma (Confidentiality, Integrity, Availability)

This trilemma reminds us that confidentiality, integrity and availability cannot all be optimized at the same time. Blockchain, Lightning and Client-side Validation fall differently into this balance. The idea is that no single system can provide everything; it is necessary to combine several approaches (blockchain's time-stamping, Lightning's synchronous approach, and local validation with RGB) to obtain a coherent package offering good guarantees in each dimension.

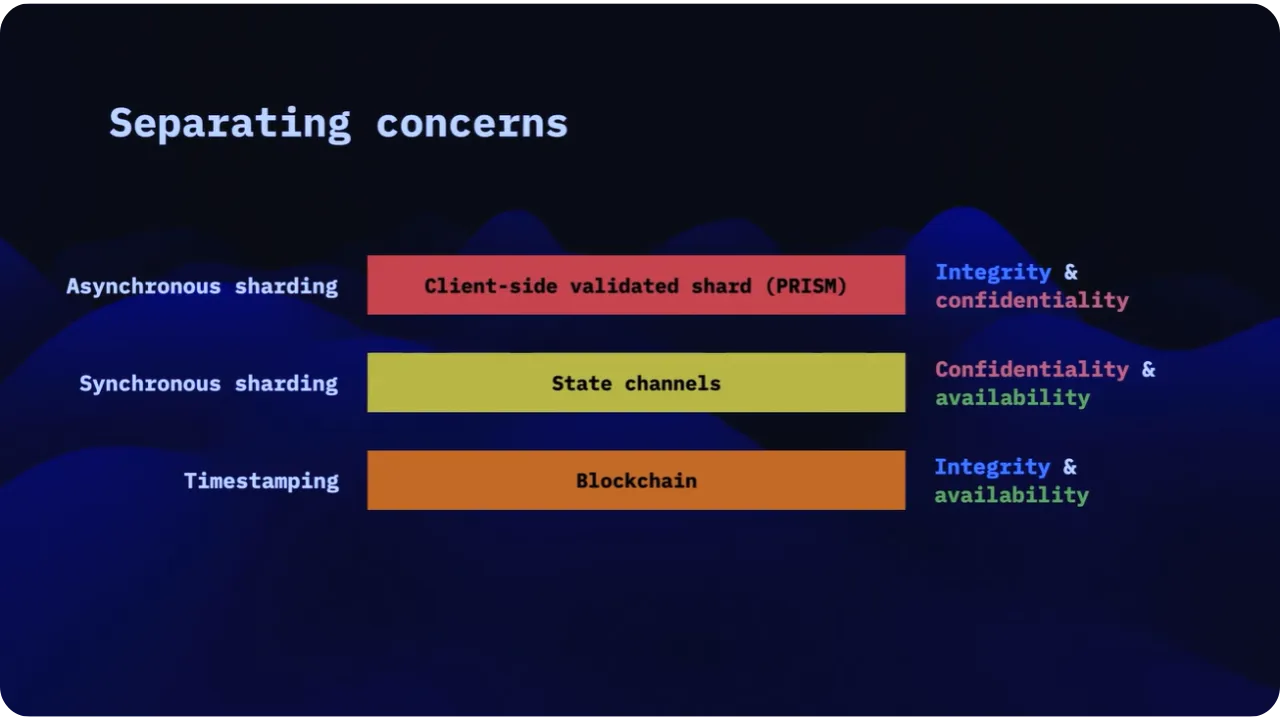

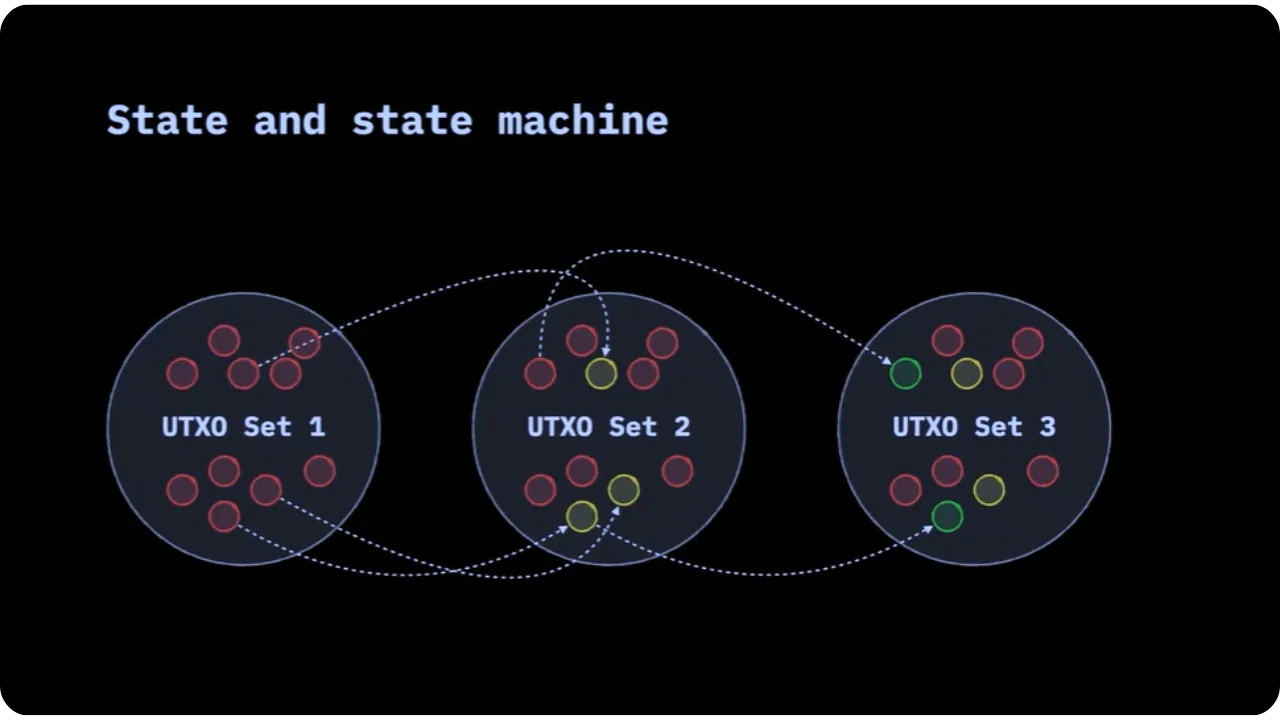

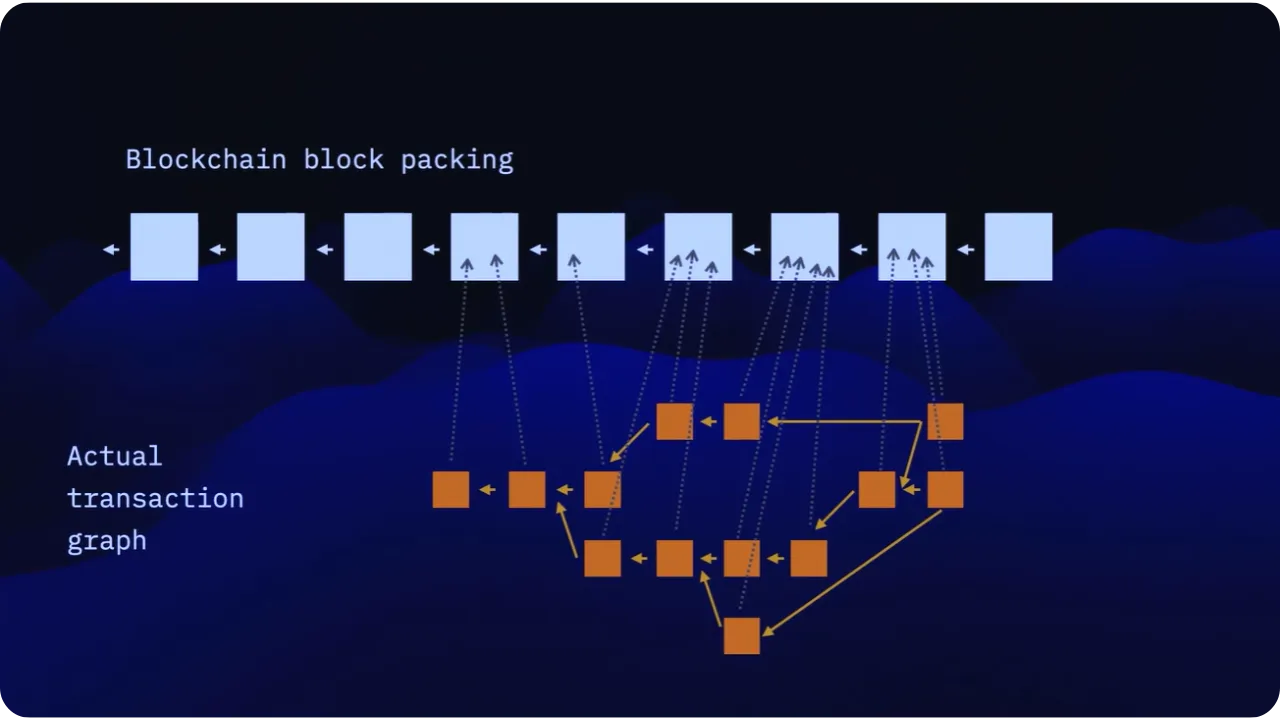

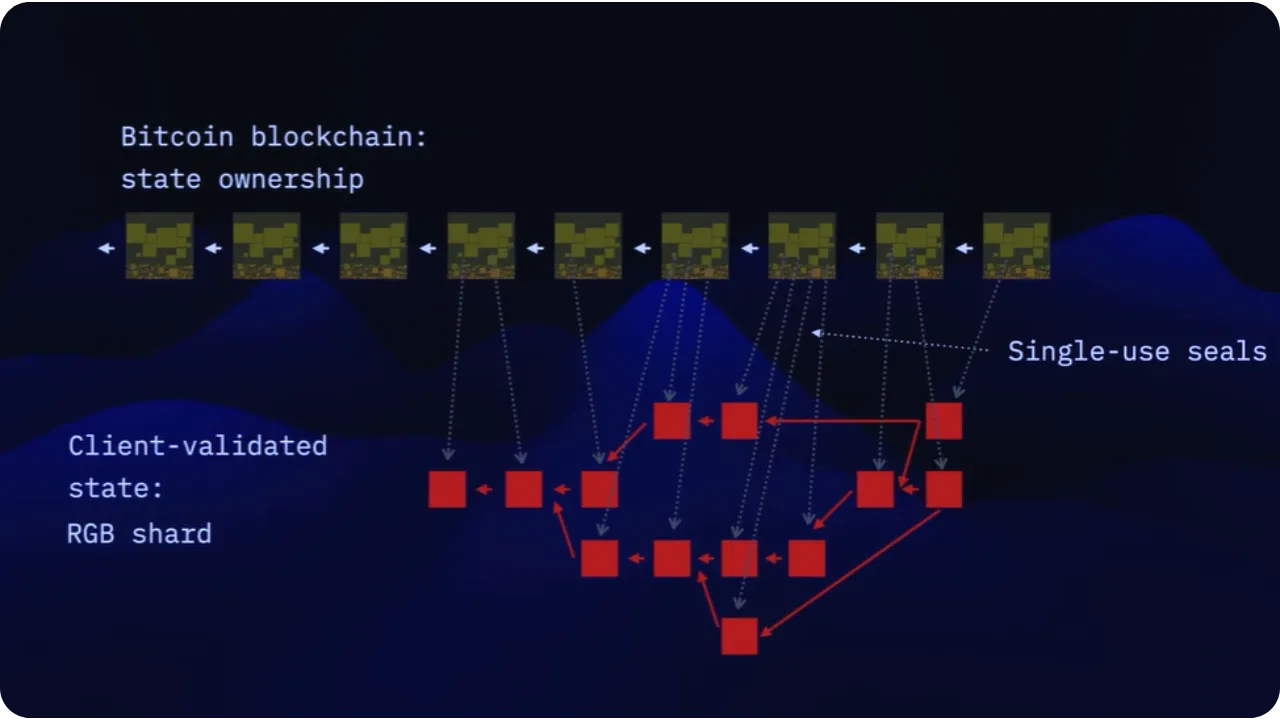

The role of blockchain and the notion of sharding

The blockchain (in this case, Bitcoin) serves primarily as a time-stamping mechanism and protection against double spending. Instead of inserting the complete data of a smart contract or decentralized system, we simply include cryptographic commitments to transactions (in the sense of Client-side Validation, which we'll call "state transitions"). Thus:

- We free the blockchain from a large amount of data and logic;

- Each user stores only the history required for his own portion of the contract (his "shard"), rather than replicating the global state.

Sharding is a concept that originated in distributed databases (e.g. MySQL for social networks such as Facebook or Twitter). To solve the problem of data volume and synchronization latencies, the database is segmented into shards (USA, Europe, Asia, etc.). Each segment is locally consistent and only partially synchronized with the others.

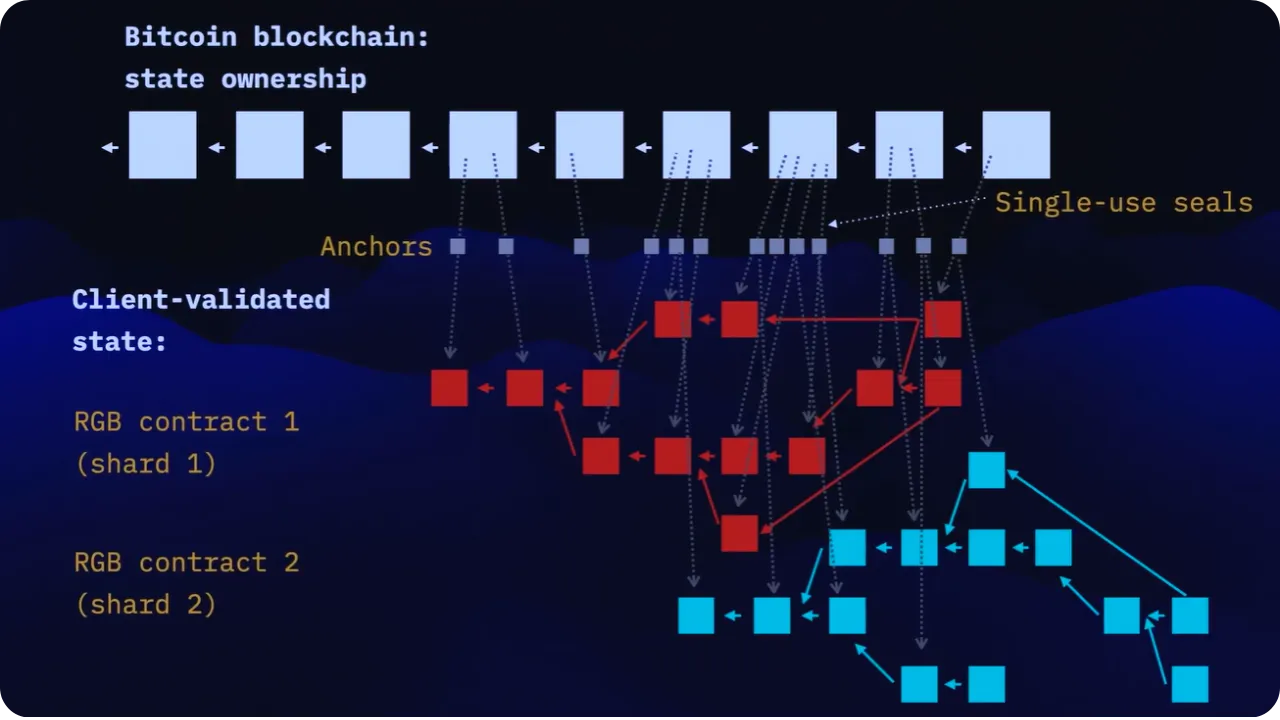

For RGB-type smart contracts, we shard according to the contracts themselves. Each contract is an independent shard. For example, if you only hold USDT tokens, you don't have to store or validate the entire history of another token like USDC. On Bitcoin, the blockchain doesn't do sharding: you have a global set of UTXOs. With Client-side Validation, each participant retains only the contract data it holds or uses.

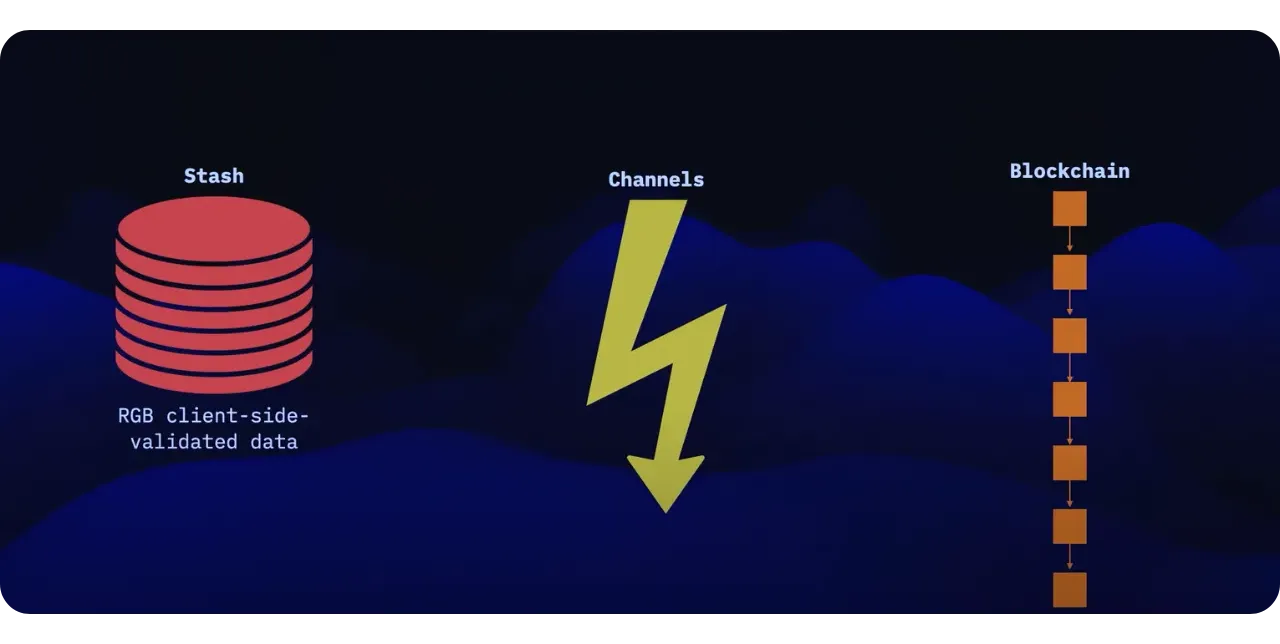

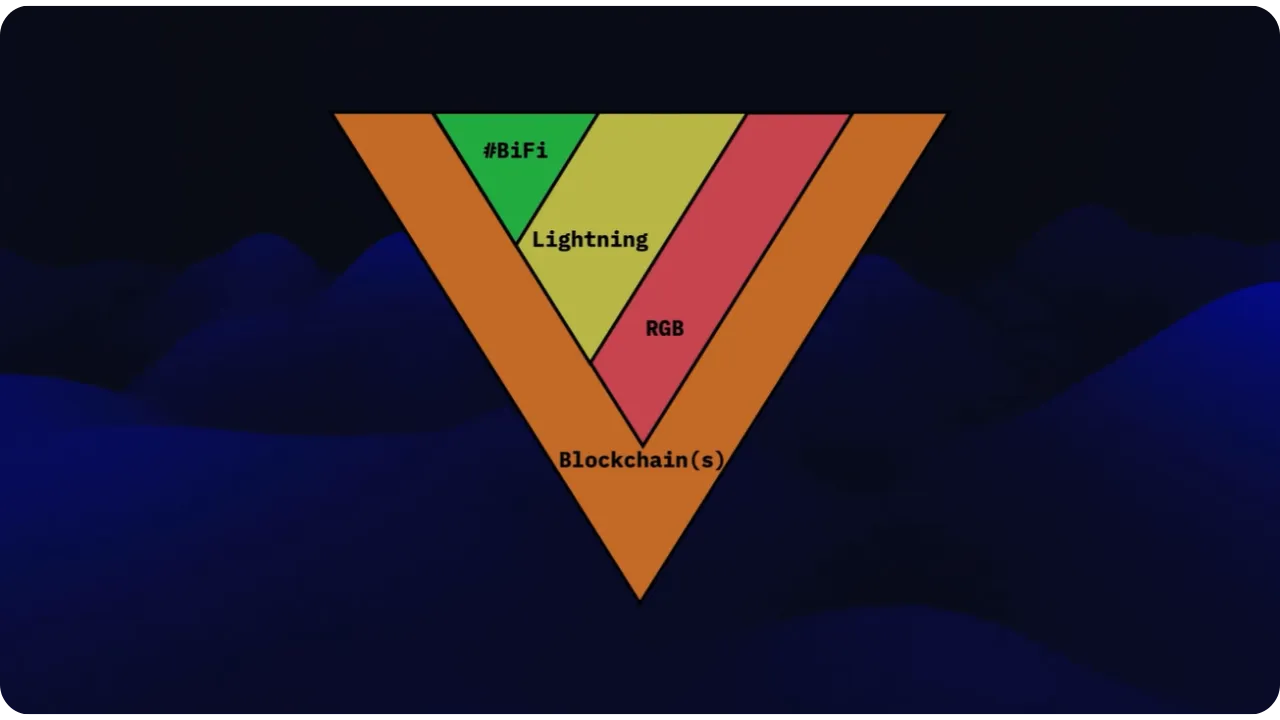

We can therefore imagine the ecosystem as follows:

- The blockchain (Bitcoin) as a foundation that ensures complete replication of a minimal register and serves as a time-stamping layer;

- The Lightning Network for fast, confidential transactions, still based on the security and final settlement of the Bitcoin blockchain;

- RGB and Client-side Validation to add more complex smart contract logic, without cluttering up the blockchain or losing confidentiality.

These three elements form a triangular whole, rather than a linear stack of "layer 2", "layer 3" and so on. Lightning can connect directly to Bitcoin, or be associated with Bitcoin transactions that incorporate RGB data. Similarly, a "BiFi" (finance on Bitcoin) can compose with the blockchain, with Lightning and with RGB according to needs for confidentiality, scalability or contract logic.

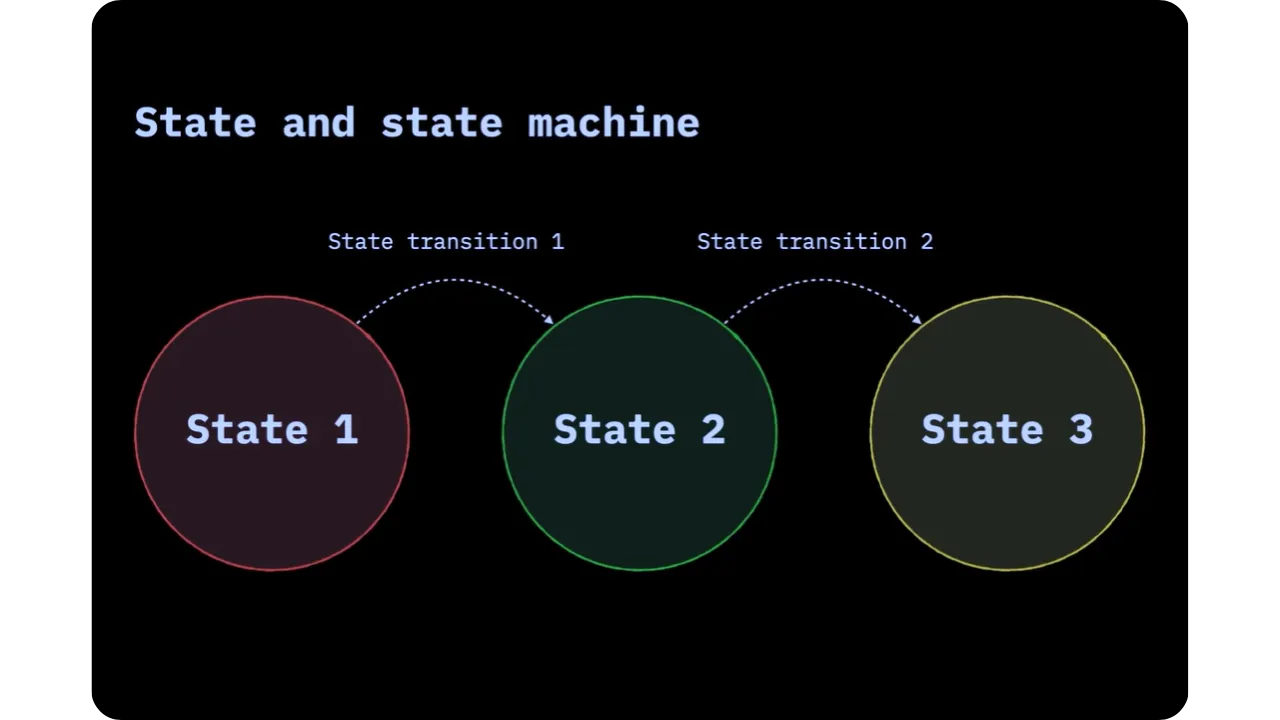

The notion of state transitions

In any distributed system, the aim of the validation mechanism is to be able to determine the validity and chronological order of state changes. The aim is to verify that the protocol rules have been respected, and to prove that these state changes follow one another in a definitive, unassailable order.

To understand how this validation works in the context of Bitcoin and, more generally, to grasp the philosophy behind Client-side Validation, let's first take a look back at the mechanisms of the Bitcoin blockchain, before seeing how Client-side Validation differs from them and what optimizations it makes possible.

In the case of the Bitcoin blockchain, transaction validation is based on a simple rule:

- All network nodes download every block and transaction;

- They validate these transactions to verify the correct evolution of the UTXO set (all unspent outputs);

- They store this data (in the form of blocks) so that the history can be replayed if necessary.

However, this model has two major drawbacks:

- Scalability: since each node must process, verify and archive everyone's transactions, there is an obvious limit to transaction capacity, linked in particular to the maximum block size (1 MB on average over 10 minutes for Bitcoin, excluding cookies);

- Privacy: everything is broadcast and stored publicly (amounts, destination addresses, etc.), which limits the confidentiality of exchanges.

In practice, this model works for Bitcoin as a base layer (Layer 1), but may become insufficient for more complex uses that simultaneously require high transaction throughput and a certain degree of confidentiality.

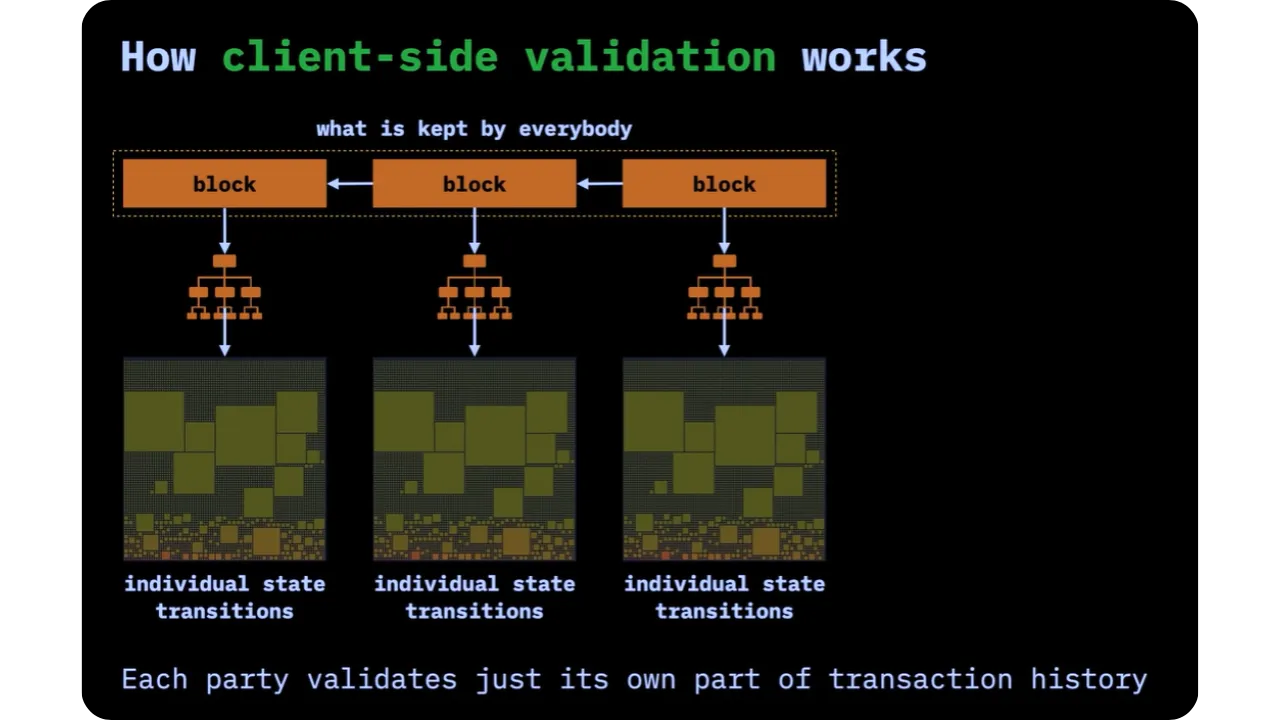

Client-side Validation is based on the opposite idea: rather than requiring the entire network to validate and store all transactions, each participant (client) will validate only the part of the history that concerns him or her:

- When a person receives an asset (or any other digital property), they only need to know and verify the chain of operations (state transitions) that lead to that asset and prove its legitimacy;

- This sequence of operations, from the Genesis (initial issue) to the most recent transaction, forms an acyclic directed graph (DAG) or shard, i.e. a fraction of the overall history.

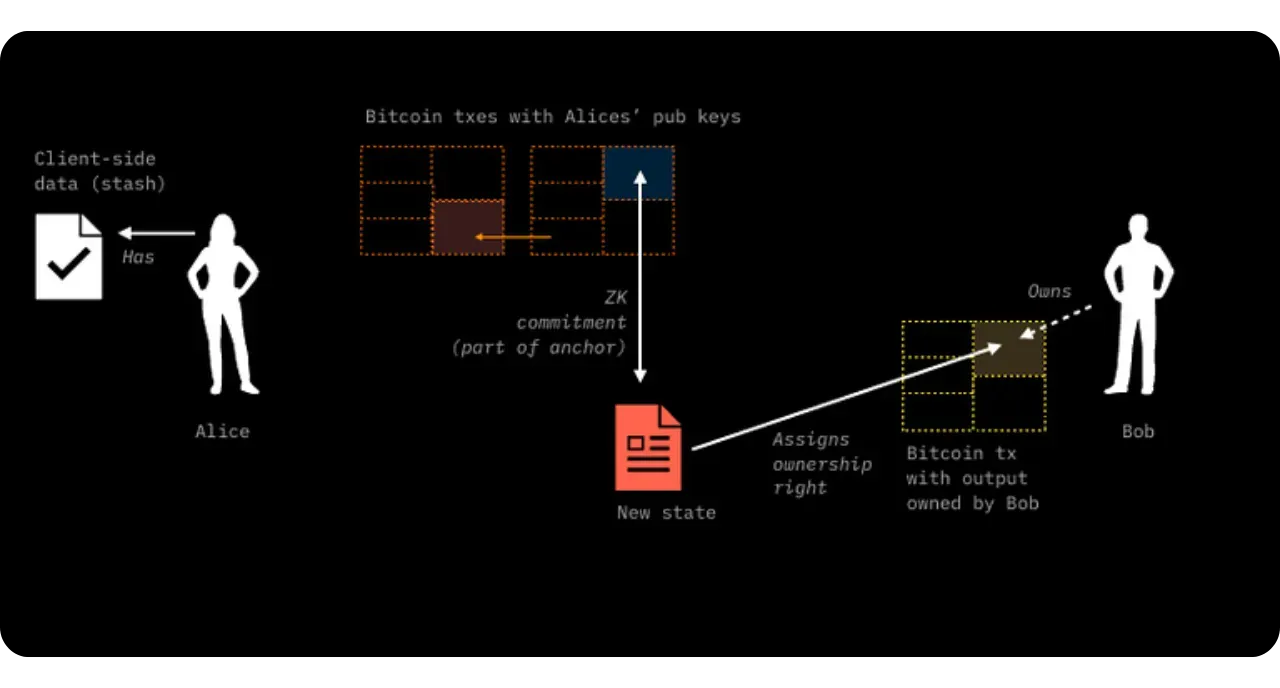

At the same time, so that the rest of the network (or more precisely, the underlying layer, such as Bitcoin) can lock in the final state without seeing the details of this data, Client-side Validation relies on the notion of commitment.

A commitment is a cryptographic commitment, typically a hash (SHA-256 for example) inserted into a Bitcoin transaction, which proves that private data has been included, without revealing this data.

Thanks to these commitments, we can prove:

- The existence of information (since it is committed to a hash);

- The anteriority of this information (because it is anchored and time-stamped in the blockchain, with a date and block order).

The exact content, however, is not revealed, thus preserving its confidentiality.

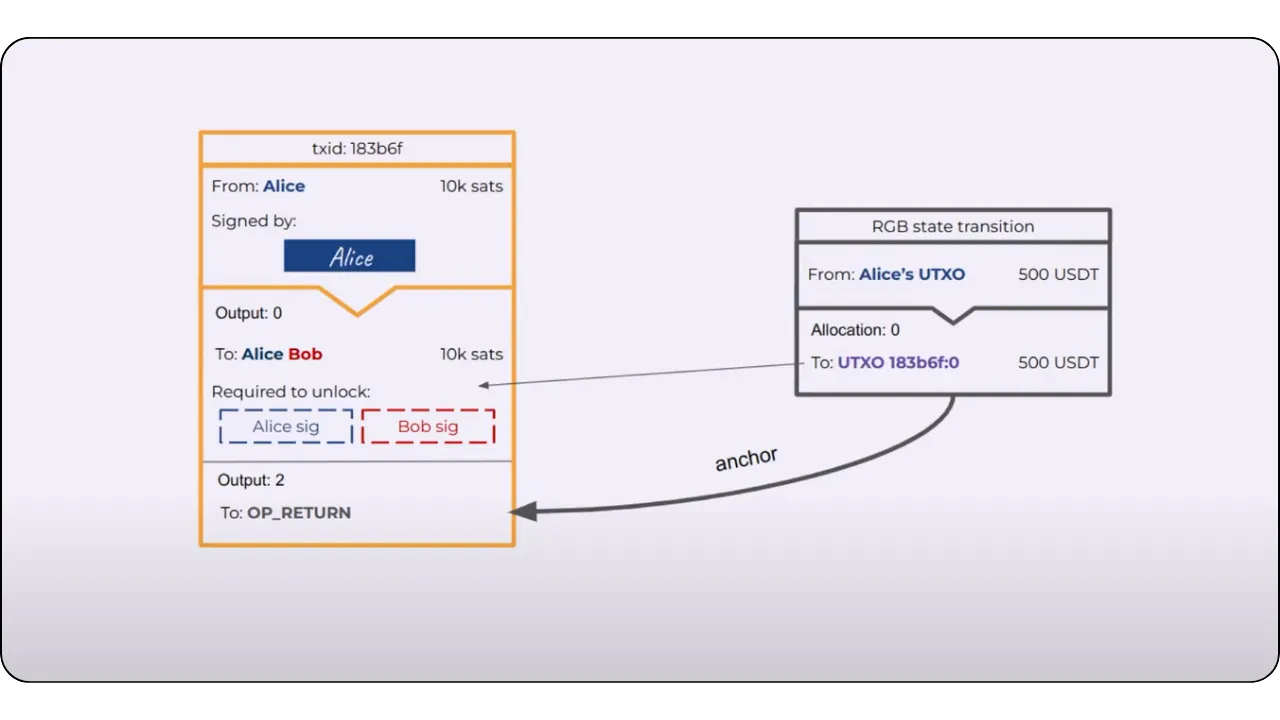

In concrete terms, here's how an RGB state transition works:

- You prepare a new state transition (e.g. the transfer of an RGB token);

- You generate a cryptographic commitment to this transition and insert it into a Bitcoin transaction (these commitments are called "anchors" in the RGB protocol);

- The counterparty (the recipient) retrieves the customer-side history associated with this asset and validates end-to-end consistency, from the genesis of the smart contract to the transition you transmit to it.

Client-side Validation offers two major benefits:

- Scalability:

The commitments included in the blockchain are small (of the order of a few dozen bytes). This ensures that block space is not saturated, as only the hash needs to be included. It also enables the off-chain protocol to evolve, as each user only has to store his or her history fragment (his or her stash).

- Privacy:

Transactions themselves (i.e. their detailed content) are not published on-chain. Only their fingerprints (hash) are. Thus, amounts, addresses and contract logic remain private, and the receiver can verify, locally, the validity of his shard by inspecting all previous transitions. There is no reason for the receiver to make this data public, except in the event of a dispute or where proof is required.

In a system like RGB, multiple state transitions from different contracts (or different assets) can be aggregated into a single Bitcoin transaction via a single commitment. This mechanism establishes a deterministic, time-stamped link between the on-chain transaction and the off-chain data (the client-side validated transitions), and enables multiple shards to be simultaneously recorded in a single anchor point, further reducing the on-chain cost and footprint.

In practice, when this Bitcoin transaction is validated, it permanently "locks" the state of the underlying contracts, since it becomes impossible to modify the hash already inscribed in the blockchain.

The stash concept

A stash is the set of client-side data that a participant must absolutely retain to maintain the integrity and history of an RGB smart contract. Unlike a Lightning channel, where certain states can be reconstructed locally from shared information, the stash of an RGB contract is not replicated elsewhere: if you lose it, no one will be able to restore it to you, as you are responsible for your share of the history. This is why you need to adopt a system with reliable backup procedures in RGB.

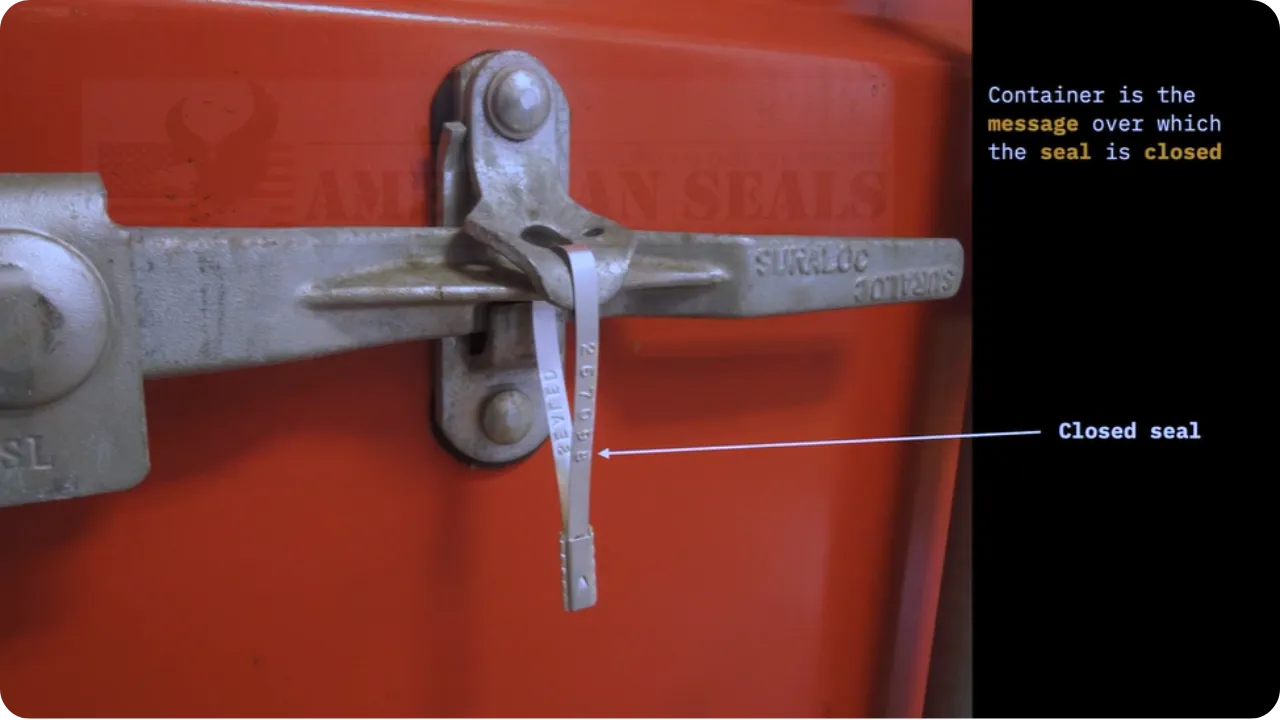

Single-use Seal: origins and operation

When accepting an asset such as a currency, two guarantees are essential:

- The authenticity of the item received;

- The uniqueness of the item received, to avoid double expenses.

For physical assets, such as a banknote, physical presence is enough to prove that it has not been duplicated. However, in the digital world, where assets are purely informational, this verification is more complex, as information can easily multiply and be duplicated.

As we saw earlier, the sender's revelation of the history of state transitions enables us to ensure the authenticity of an RGB token. By having access to all transactions since the genesis transaction, we can confirm the token's authenticity. This principle is similar to that of Bitcoin, where the history of coins can be traced back to the original coinbase transaction to verify their validity. However, unlike Bitcoin, this history of state transitions in RGB is private and kept on the client side.

To prevent double-spending of RGB tokens, we use a mechanism called "Single-use Seal". This system ensures that each token, once used, cannot be fraudulently reused a second time.

Single-use Seals are cryptographic primitives, proposed in 2016 by Peter Todd, akin to the concept of physical seals: once a seal has been placed on a container, it becomes impossible to open or modify it without irreversibly breaking the seal.

This approach, transposed to the digital world, makes it possible to prove

that a sequence of events has indeed taken place, and that it can no longer

be altered a posteriori. Single-use Seals thus go beyond the simple logic of hash + timestamp, adding the notion of a seal that can be closed only once.

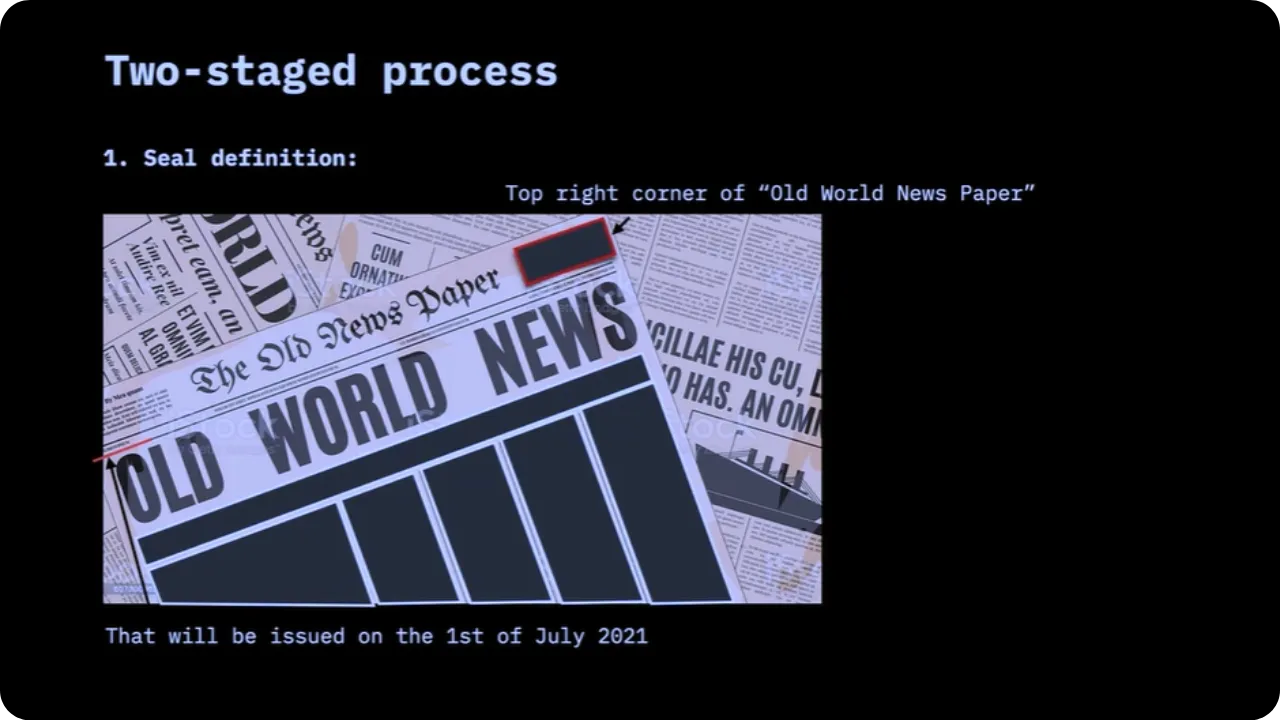

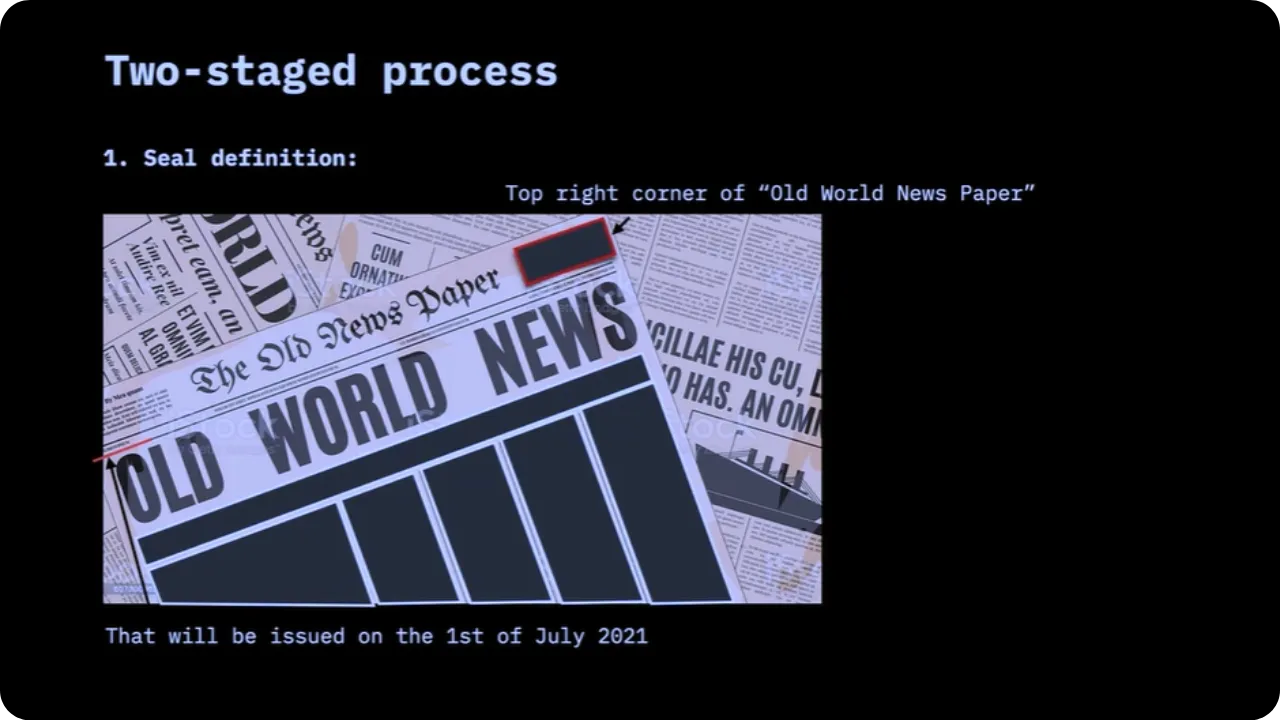

For Single-use Seals to work, you need a publication proof medium capable of proving the existence or absence of a publication, and difficult (if not impossible) to falsify once the information has been disseminated. A blockchain (like Bitcoin) can fill this role, as can a paper newspaper with a public circulation do, as an example. The idea is as follows:

- We want to prove that a certain commitment on a message

h(m)has been published to an audience without revealing the content of the messagem; - We want to prove that no other competing

h(m')message commitment has been published in place ofh(m); - We also want to be able to check that message

mexists before a certain date.

A blockchain lends itself ideally to this role: as soon as a transaction is included in a block, the whole network has the same unfalsifiable proof of its existence and content (at least in part, since the commitment can hide the details while proving the authenticity of the message).

A Single-use Seal can therefore be seen as a formal promise to publish a message (still unknown at this stage) once and only once, in a way that can be verified by all interested parties.

Unlike simple commitments (hash) or timestamps, which attest to a date of existence, a Single-use Seal offers the additional guarantee that no alternative commitment can coexist: you can't close the same seal twice, or attempt to replace the sealed message.

The following comparison helps to understand this principle:

- Cryptographic commitment (hash): With a hash function, you can commit to a piece of data (a number) by publishing its hash. The data remains secret until you reveal the pre-image, but you can prove that you knew it in advance;

- Timestamp (blockchain): By inserting this hash in the blockchain, we also prove that we knew it at a precise moment (that of inclusion in a block);

- Single-use Seal: With single-use seals, we go one step further by making the commitment unique. With a single hash, you can create several contradictory commitments in parallel (the problem of the doctor who announces "It's a boy" to the family and "It's a girl" in his personal diary). The Single-use Seal eliminates this possibility by connecting the commitment to a proof-of-publication medium, such as the Bitcoin blockchain, so that an expenditure of UTXO definitively seals the commitment. Once spent, the same UTXO cannot be re-spent to replace the commitment.

- Cryptographic commitment (hash): With a hash function, you can commit to a piece of data (a number) by publishing its hash. The data remains secret until you reveal the pre-image, but you can prove that you knew it in advance;

- Timestamp (blockchain): By inserting this hash in the blockchain, we also prove that we knew it at a precise moment (that of inclusion in a block);

- Single-use Seal: With single-use seals, we go one step further by making the commitment unique. With a single hash, you can create several contradictory commitments in parallel (the problem of the doctor who announces "It's a boy" to the family and "It's a girl" in his personal diary). The Single-use Seal eliminates this possibility by connecting the commitment to a proof-of-publication medium, such as the Bitcoin blockchain, so that an expenditure of UTXO definitively seals the commitment. Once spent, the same UTXO cannot be re-spent to replace the commitment.

| Simple commitment (digest/hash) | Timestamps | Single-use seals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publishing the commitment does not reveal the message | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Proof of the commitment date / existence of the message before a certain date | Impossible | Possible | Possible |

| Proof that no alternative commitment can exist | Impossible | Impossible | Possible |

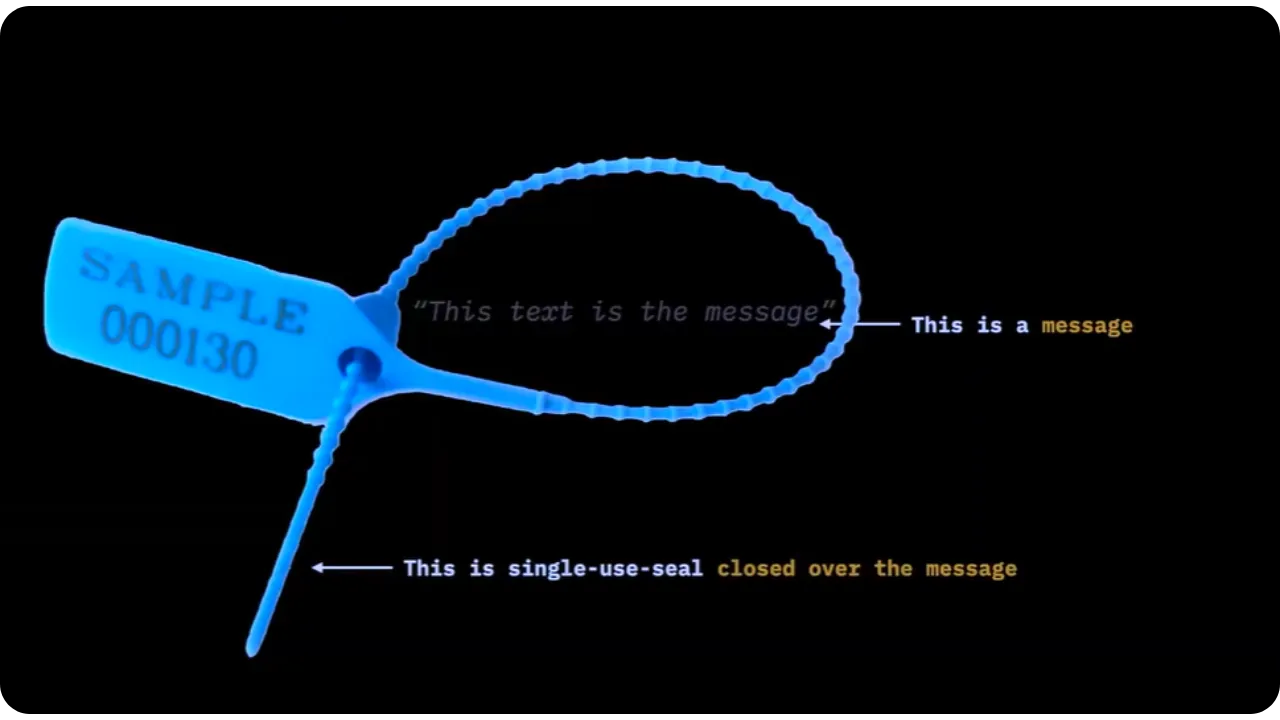

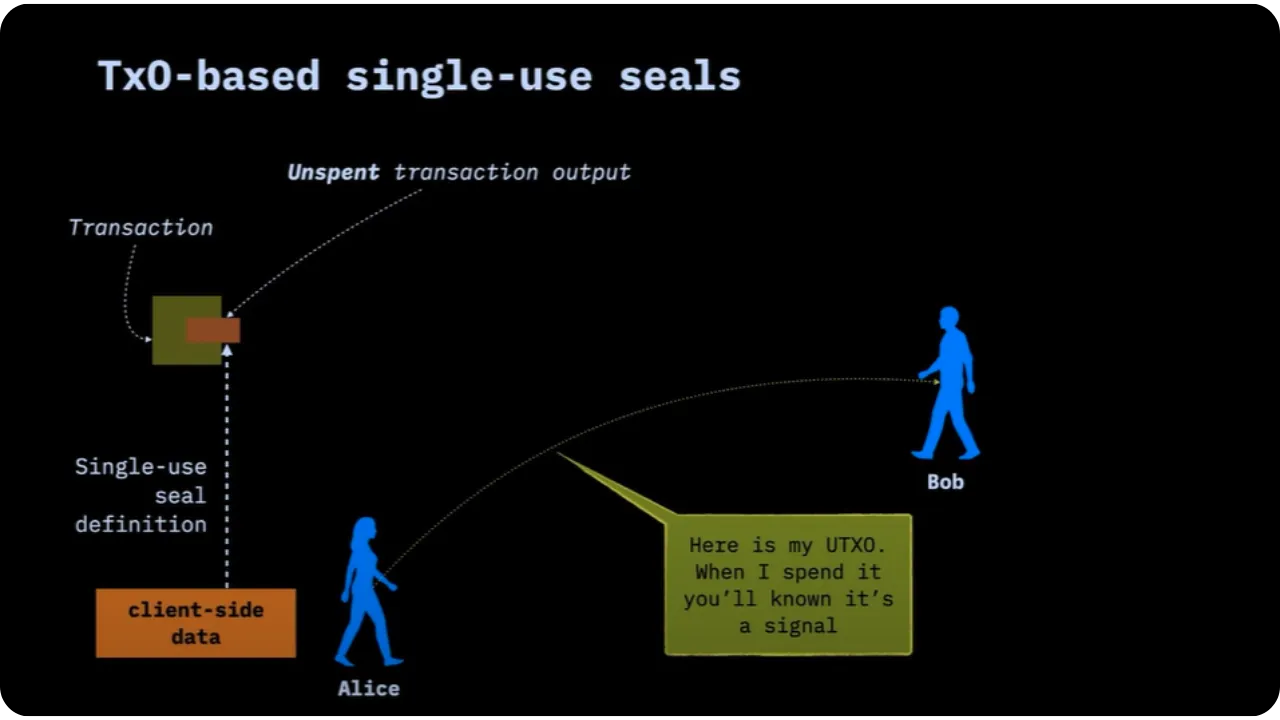

Single-use Seals work in three main stages:

Seal Definition:

- Alice defines in advance the rules for publishing the seal (when, where and how the message will be published);

- Bob accepts or acknowledges these conditions.

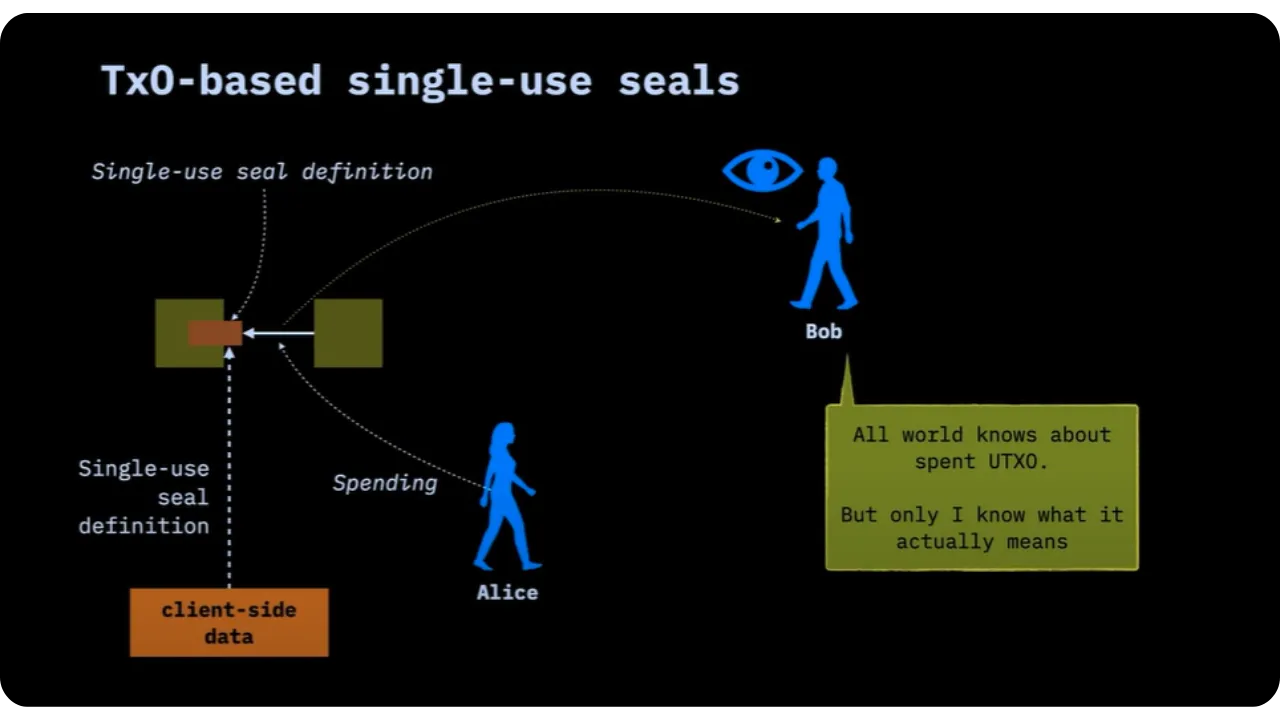

Seal Closing:

- At runtime, Alice closes the seal by publishing the actual message (usually in the form of a commitment, e.g. a hash);

- It also provides a witness (cryptographic proof) proving that the seal is closed and irrevocable.

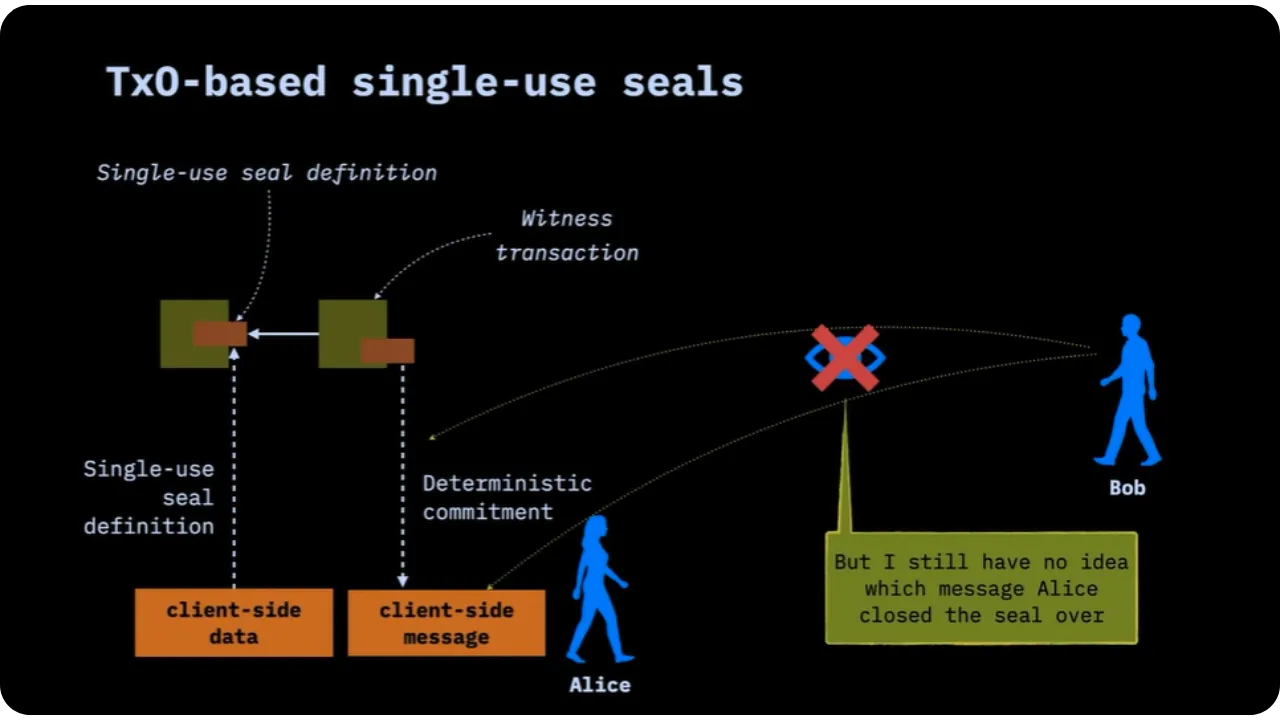

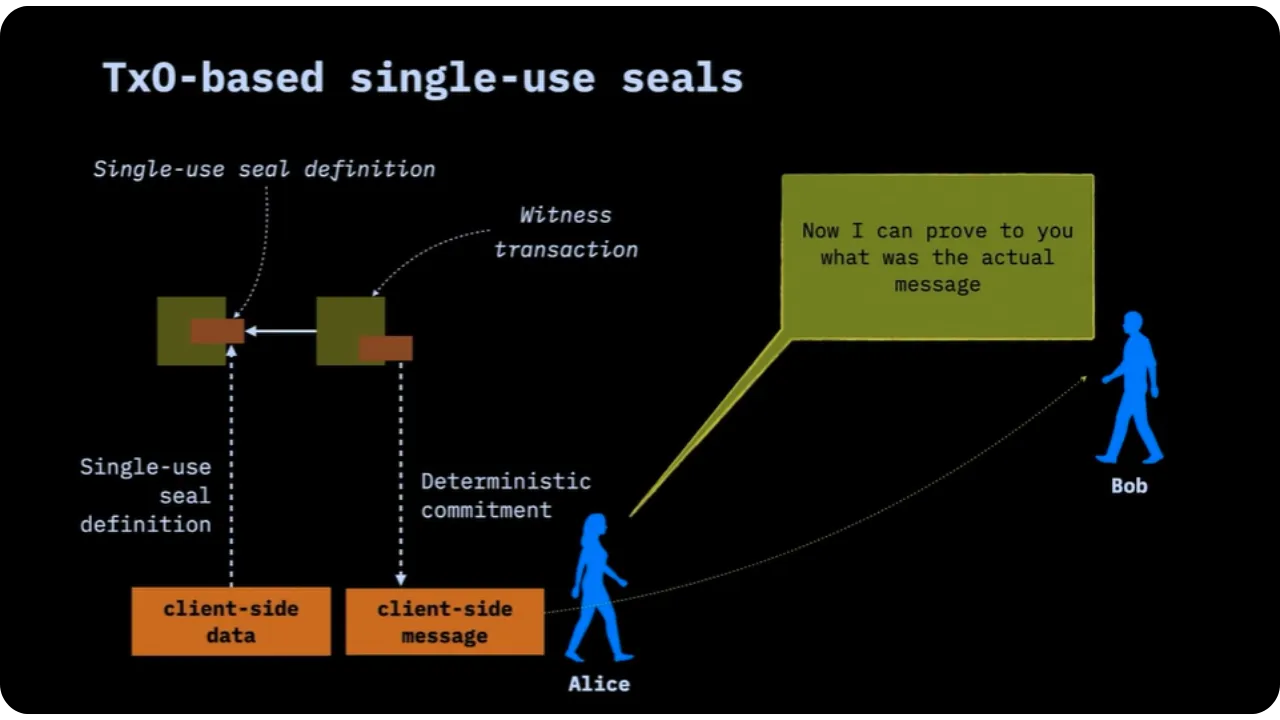

Seal Verification:

- Once the seal is closed, Bob can no longer open it: he can only check that it has been closed;

- Bob collects the seal, the witness and the message (or his commitment) to make sure that everything matches and that there are no competing seals or different versions.

The process can be summarized as follows:

# Defined by Alice, validated or accepted by Bob

seal <- Define()

# Seal is closed by Alice with the message

witness <- Close(seal, message)

# Verification by Bob

bool <- Verify(seal, witness, message)

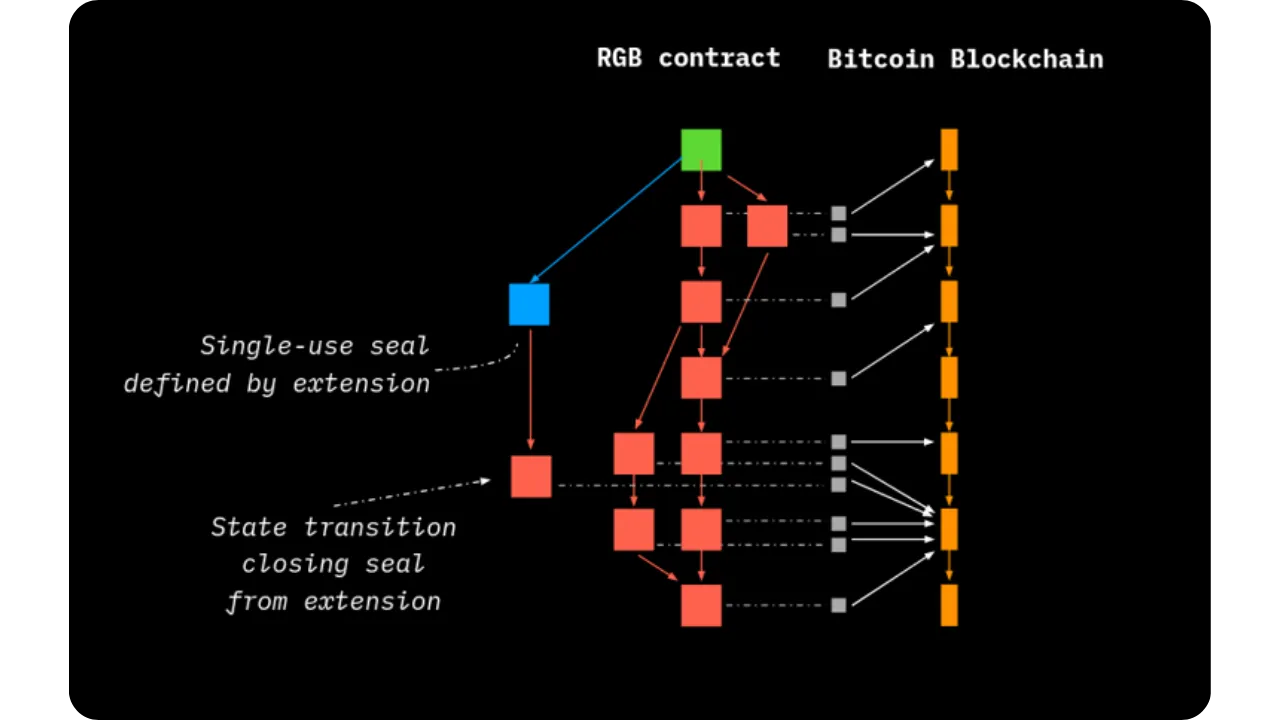

Client-side validation, however, goes one step further: if the definition of a seal itself remains outside the blockchain, it is possible (in theory) for someone to challenge the existence or legitimacy of the seal in question. To overcome this problem, a chain of interlocking Single-use Seals is used:

- Each closed seal contains the definition of the following seal;

- We register these closures (with their commitments) within the blockchain (in a Bitcoin transaction);

- Thus, any attempt to modify a previous seal would contradict the history embedded in Bitcoin.

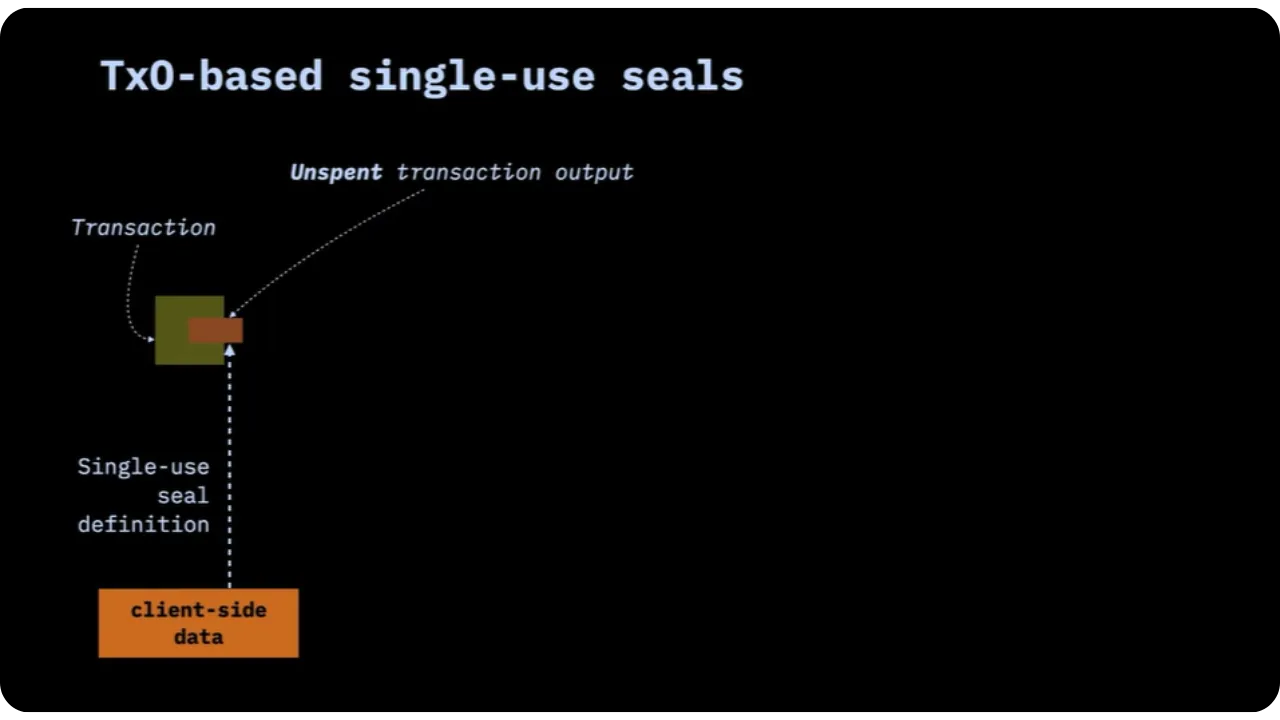

This is precisely what the RGB system does:

- Published messages are commitments to client-side validated data;

- The seal definition is associated with a Bitcoin UTXO;

- The seal closes when this UTXO is spent or when a new output is credited to the same commitment;

- The transaction chain that spends these UTXOs corresponds to the proof of publication: every transition or change of state on RGB is thus anchored in Bitcoin.

To sum up:

- The seal definition is the UTXO you intend to seal a future commitment;

- The seal closing occurs when you spend this UTXO, creating a transaction that contains the commitment;

- The witness is the transaction itself, which proves that you have closed the seal with this content;

- You can't prove that a seal hasn't been closed (you can't be absolutely sure that a UTXO hasn't already been spent or won't be spent in a block you haven't seen yet), but you can prove that it has indeed been closed.

This uniqueness is important for Client-side Validation: when you validate a state transition, you check that it corresponds to a unique UTXO, not previously spent in a competing commitment. This is what guarantees the absence of double spending in off-chain smart contracts.

Multiple commitments and roots

An RGB smart contract may need to spend several Single-use Seals (several UTXOs) simultaneously. What's more, a single Bitcoin transaction may reference several distinct contracts, each sealing its own state transition. This requires a multi-commitment mechanism to prove, deterministically and uniquely, that none of the commitments exists in duplicate. This is where the notion of anchor comes into play in RGB: a special structure linking a Bitcoin transaction and one or more client-side commitments (state transitions), each potentially belonging to a different contract. We'll take a closer look at this concept in the next chapter.

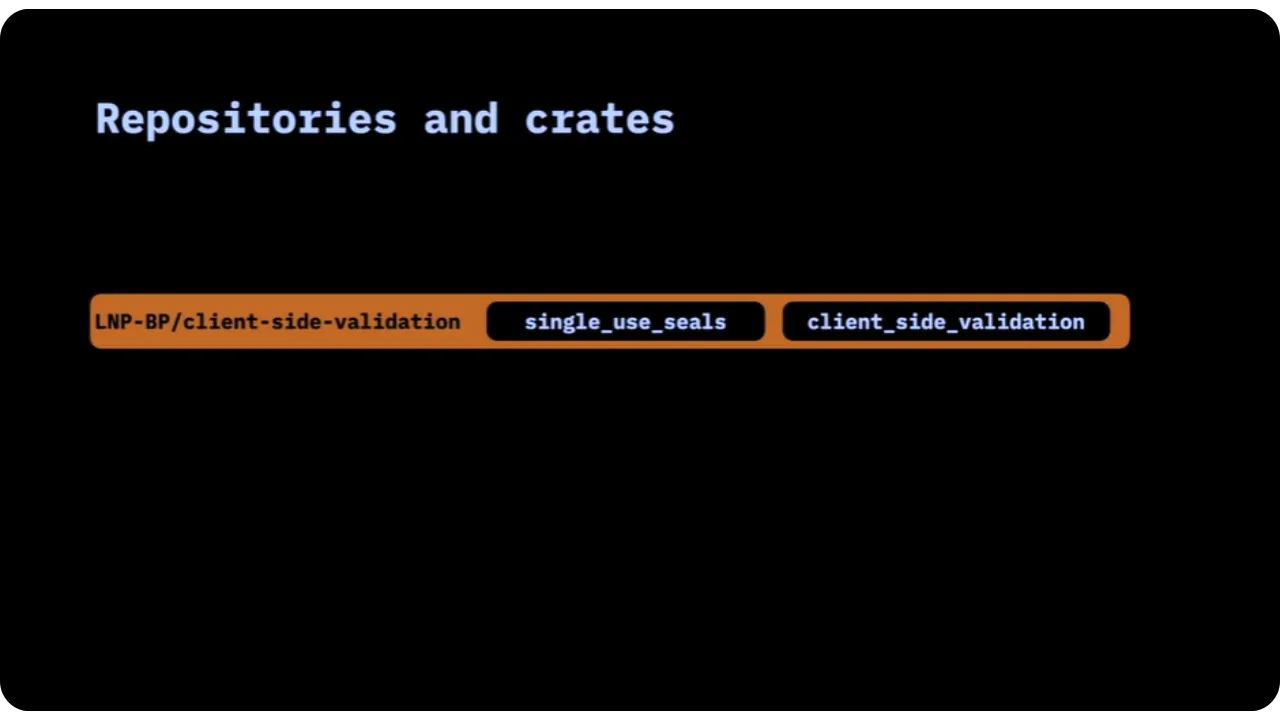

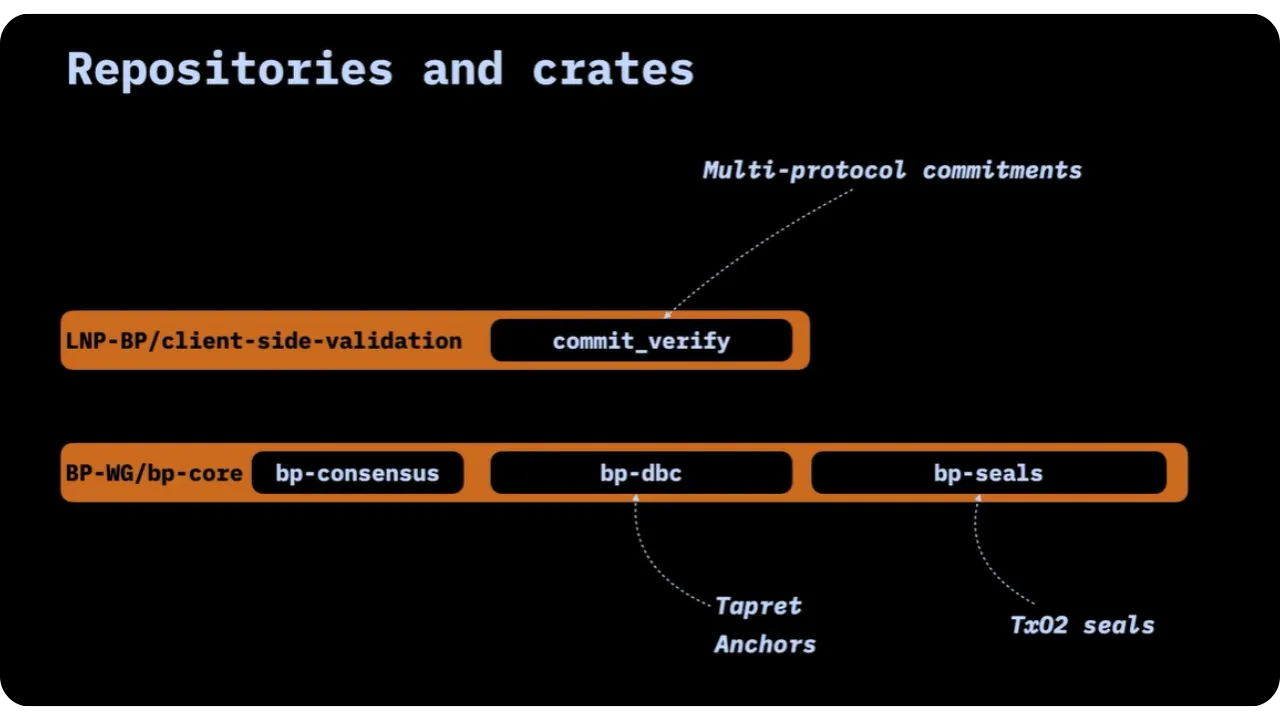

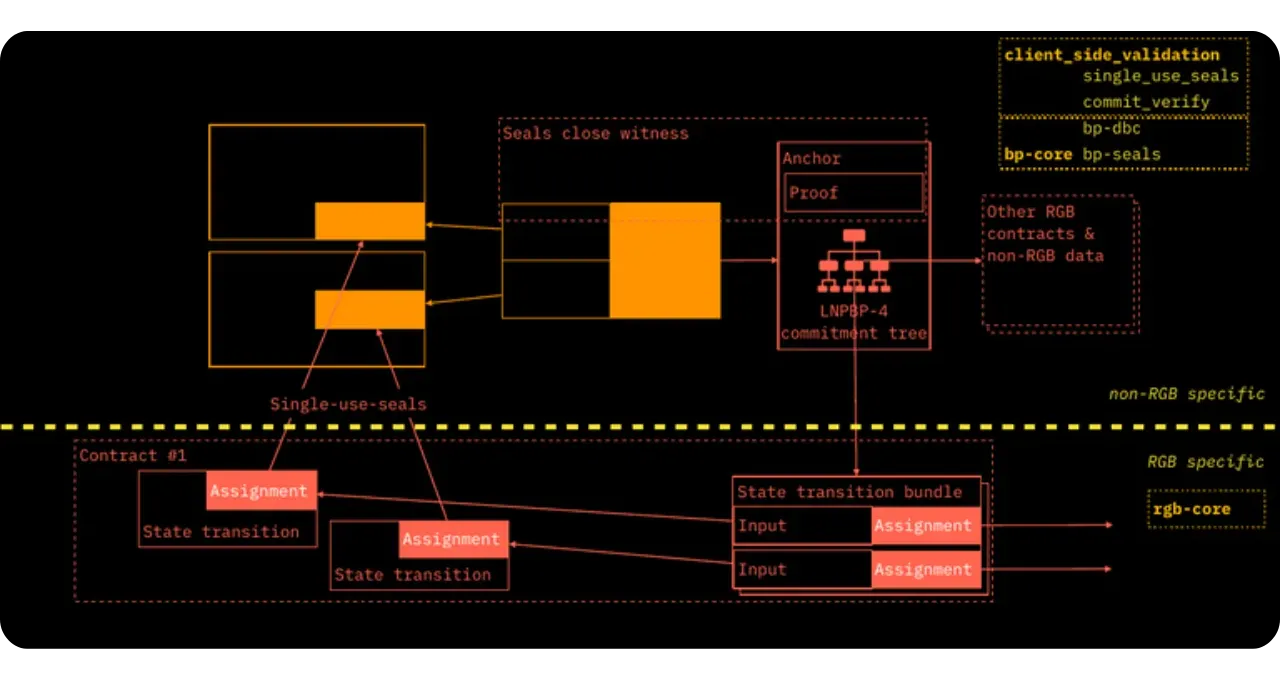

Two of the project's main GitHub repositories (under the LNPBP organization) group together the basic implementations of these concepts studied in the first chapter:

- client_side_validation: Contains Rust primitives for local validation;

- single_use_seals: Implements the logic to define and close these seals securely.

Note that these software bricks are Bitcoin agnostic; in theory, they could be applied to any other proof-of-publication medium (another registry, a journal, etc.). In practice, RGB relies on Bitcoin for its robustness and broad consensus.

Questions from the public

Towards wider use of Single-use Seals

Peter Todd also created the Open Timestamps protocol, and the Single-use Seal concept is a natural extension of these ideas. Beyond RGB, other use cases can be envisaged, such as the construction of sidechains without resorting to merge mining or drivechain-related proposals like BIP300. Any system requiring a single commitment can, in principle, exploit this cryptographic primitive. Today, RGB is the first major full-scale implementation.

Data availability problems

Since in Client-side Validation, each user stores his or her own part of the history, data availability is not guaranteed globally. If a contract issuer withholds or revokes certain information, you may be unaware of the actual evolution of the offer. In some cases (such as stablecoins), the issuer is expected to maintain public data to prove the volume in circulation, but there is no technical obligation to do so. It is therefore possible to design deliberately opaque contracts with unlimited supply, which raises questions of trust.

Sharding and contract isolation

Each contract represents an isolated shard: USDT and USDC, for example, do not have to share their histories. Atomic swaps are still possible, but this does not involve merging their registers. Everything is done by cryptographic commitment, without disclosing the entire history graph to each participant.

Conclusion

We've seen where the concept of Client-side Validation fits in with blockchain and state channels, how it responds to distributed computing trilemmas, and how it leverages the Bitcoin blockchain uniquely to avoid double-spending and for time-stamping. The idea is based on the notion of Single-use Seal, enabling the creation of unique commitments that you can't re-spend at will. In this way, each participant uploads only the history that is strictly necessary, increasing the scalability and confidentiality of smart contracts while retaining the security of Bitcoin as a backdrop.

The next step will be to explain in more detail how this Single-use Seal mechanism is applied in Bitcoin (via UTXOs), how anchors are created and validated, and then how complete smart contracts are built in RGB. In particular, we'll look at the issue of multiple commitments, the technical challenge of proving that a Bitcoin transaction simultaneously seals multiple state transitions in different contracts, without introducing vulnerabilities or double commitments.

Before diving into the more technical details of the second chapter, feel free to reread the key definitions (Client-side Validation, Single-use Seal, anchors, etc.) and keep in mind the overall logic: we're looking to reconcile the strengths of the Bitcoin blockchain (security, decentralization, time-stamping) with those of off-chain solutions (speed, confidentiality, scalability), and this is precisely what RGB and Client-side Validation are trying to achieve.

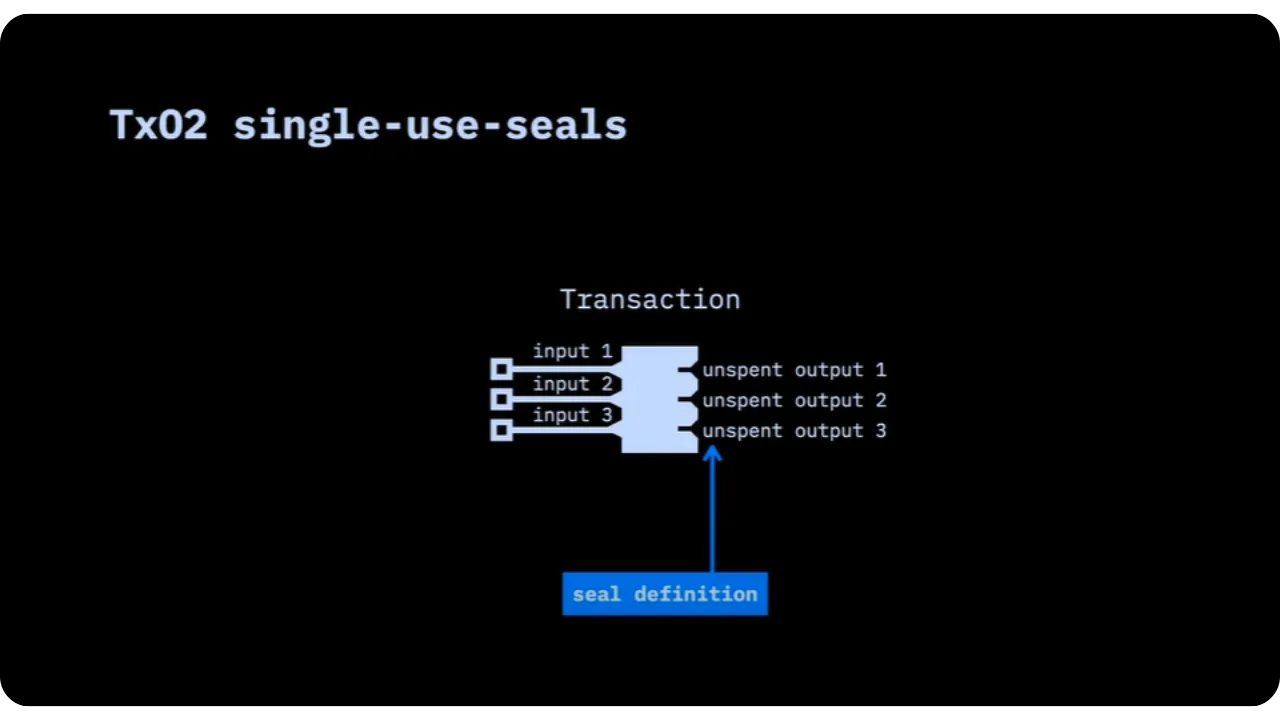

The commitment layer

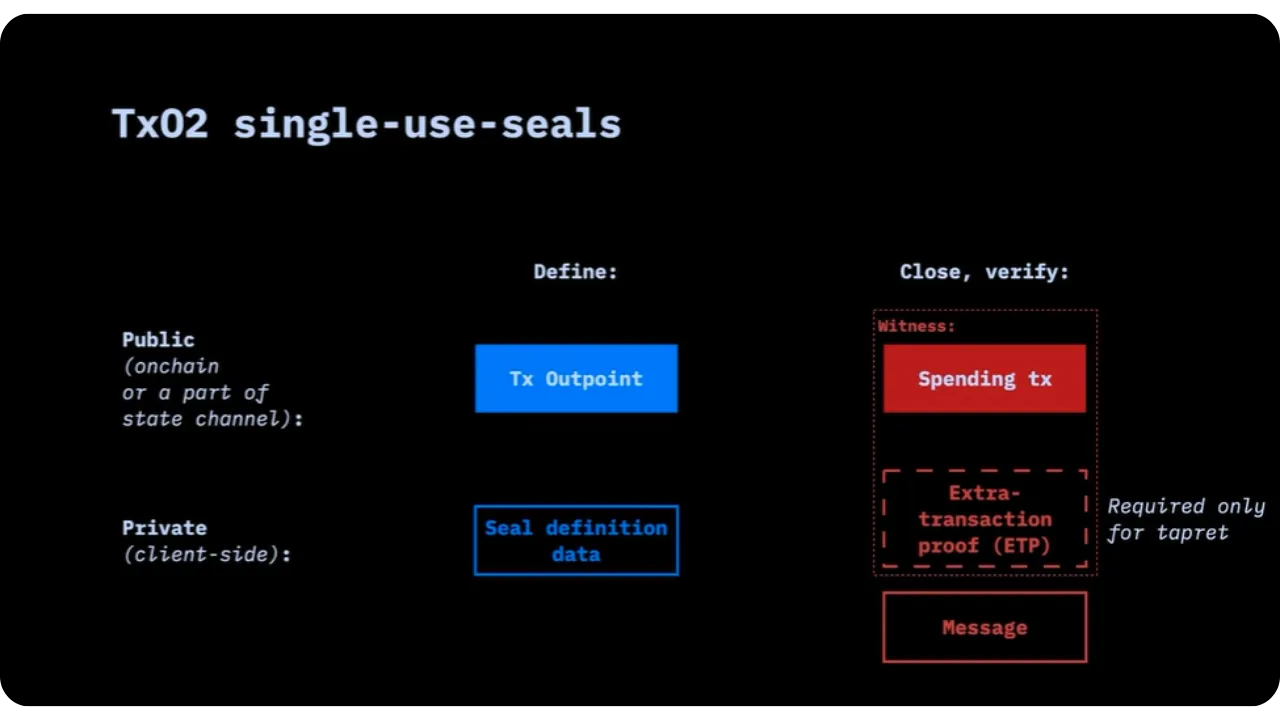

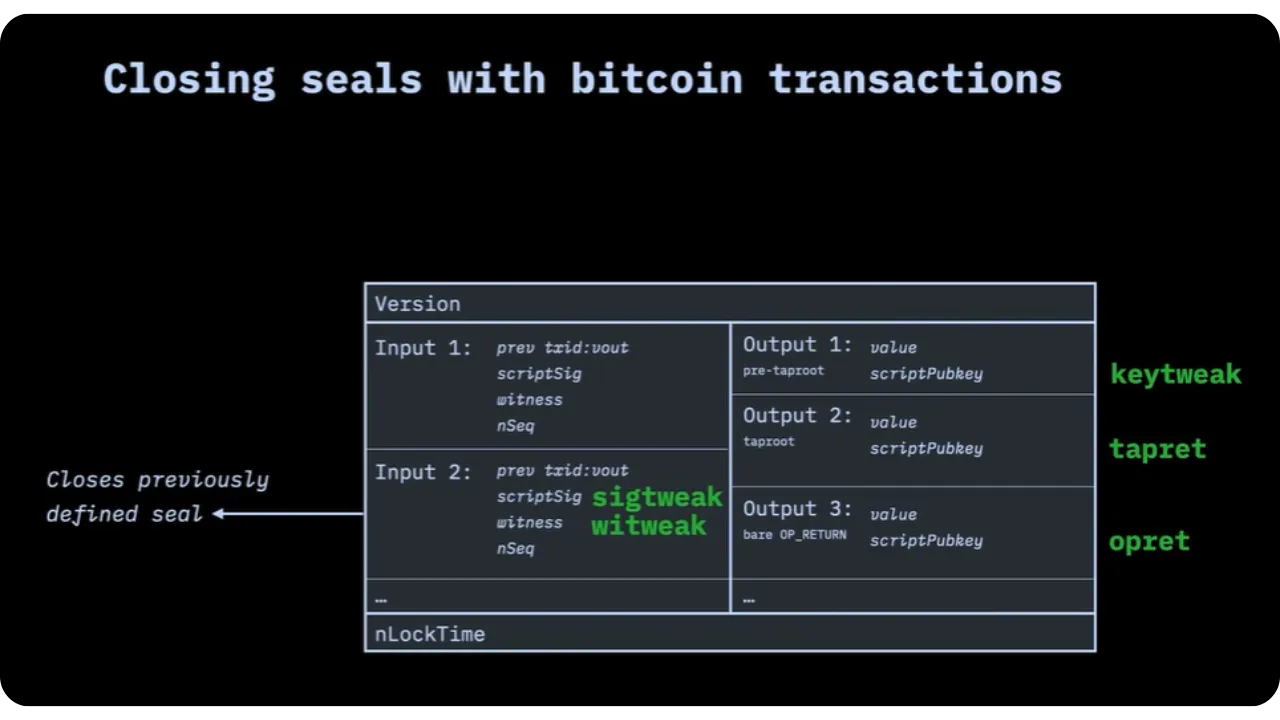

In this chapter, we'll look at the implementation of Client-side Validation and Single-use Seals within the Bitcoin blockchain. We'll present the main principles of RGB's commitment layer (layer 1), with a particular focus on the TxO2 scheme, which RGB uses to define and close a seal in a Bitcoin transaction. Next, we'll discuss two important points that haven't yet been covered in detail:

- The deterministic Bitcoin commitments;

- Multi-protocol commitments.

It is the combination of these concepts that enables us to superimpose several systems or contracts on top of a single UTXO and therefore a single blockchain.

It should be remembered that the cryptographic operations described can be applied, in absolute terms, to other blockchains or publishing media, but Bitcoin's characteristics (in terms of decentralization, resistance to censorship and openness to all) make it the ideal foundation for developing advanced programmability such as that required by RGB.

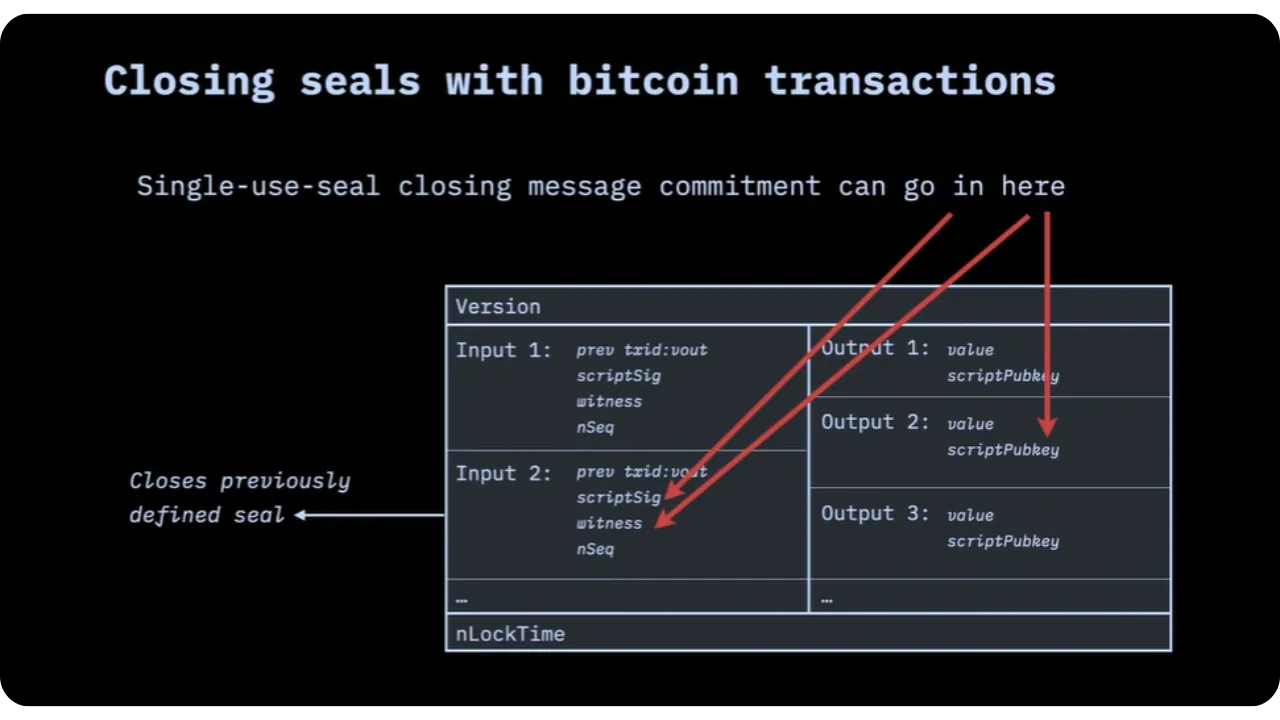

Commitment schemes in Bitcoin and their use by RGB

As we saw in the first chapter of the course, Single-use Seals are a general concept: we make a promise to include a commitment (commitment) in a specific location of a transaction, and this location acts like a seal that we close on a message. However, on the Bitcoin blockchain, there are several options for choosing where to place this commitment.

To understand the logic, let's recall the basic principle: to close a single-use seal, we spend the sealed area by inserting the commitment on a given message. In Bitcoin, this can be done in a number of ways:

- Use a public key or address

We can decide that a specific public key or address is the single-use seal. As soon as this key or address appears on-chain in a transaction, it means that the seal is closed with a certain message.

- Use a Bitcoin transaction output

This means that a single-use seal is defined as a precise outpoint (a TXID + output number pair). As soon as this outpoint is spent, the seal is closed.

While working on RGB, we identified at least 4 different ways to implement these seals on Bitcoin:

- Define the seal via a public key, and close it in an output;

- Define the seal with an outpoint and close it with an output;

- Define the seal via the value of a public key, and close it in a input;

- Define the seal via an outpoint, and close it in an input.

| Schema Name | Seal Definition | Seal Closure | Additional Requirements | Main Application | Possible Commitment Schemes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PkO | Public Key Value | Transaction Output | P2(W)PKH | None at the moment | Keytweak, taptweak, opret |

| TxO2 | Transaction Output | Transaction Output | Requires deterministic commitments on Bitcoin | RGBv1 (universal) | Keytweak, tapret, opret |

| PkI | Public Key Value | Transaction Input | Taproot only & not compatible with legacy wallets | Bitcoin-based identities | Sigtweak, witweak |

| TxO1 | Transaction Output | Transaction Input | Taproot only & not compatible with legacy wallets | None at the moment | Sigtweak, witweak |

We won't go into detail about each of these configurations, as in RGB we've chosen to use an outpoint as the definition of the seal, and to place the commitment in the output of the transaction spending this outpoint. We can therefore introduce the following concepts for the sequel:

- "Seal definition ": A given outpoint (identified by TXID + output no.);

- "Seal closing ": The transaction that spends this outpoint, in which a commitment is added to a message.

This scheme has been selected for its compatibility with RGB architecture, but other configurations could be useful for different uses.

The "O2" in "TxO2" reminds us that both definition and closure are based on the expenditure (or creation) of a transaction output.

TxO2 diagram example

As a reminder, defining a single-use seal does not necessarily require publishing an on-chain transaction. It's enough for Alice, for example, to already have an unspent UTXO. She can decide: "This outpoint (already existing) is now my seal". She notes this locally (client-side), and until this UTXO is spent, the seal is considered open.

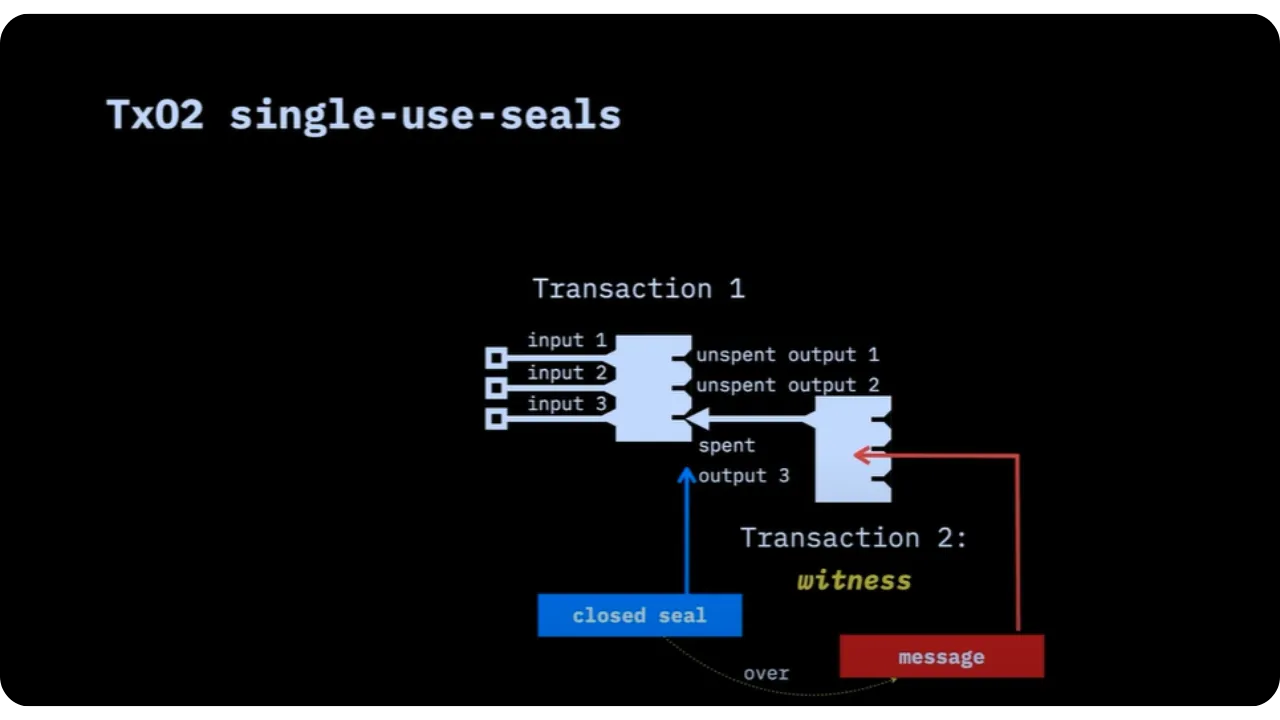

On the day it wants to close the seal (to signal an event, or to anchor a particular message), it spends this UTXO in a new transaction (this transaction is often called the "witness transaction" (unrelated to segwit, it's just the term we give it). This new transaction will contain the commitment to the message.

Note that in this example:

- No one but Bob (or the people to whom Alice chooses to reveal the full proof) will know that a certain message is hidden in this transaction;

- Everyone can see that the outpoint has been spent, but only Bob holds the proof that the message is actually anchored in the transaction.

To illustrate this TxO2 scheme, we can use a single-use seal as a mechanism for revoking a PGP key. Instead of publishing a revocation certificate on servers, Alice can say: "This Bitcoin output, if spent, means that my PGP key is revoked".

Alice therefore has a specific UTXO, to which a certain state or data (known only to her) is associated locally (on the client side).

Alice informs Bob that if this UTXO is spent, a particular event will be deemed to have occurred. From the outside, all we see is a Bitcoin transaction; but Bob knows that this expenditure has a hidden meaning.

As Alice spends this UTXO, she closes the seal on a message indicating her new key, or simply the revocation of the old one. In this way, anyone monitoring on-chain will see that the UTXO is spent, but only those with the full proof will know that it is precisely the revocation of the PGP key.

In order for Bob or anyone else involved to check the hidden message, Alice must provide him with off-chain information.

Alice must therefore provide Bob with the following:

- The message itself (for example, the new PGP key);

- Cryptographic proof that the message was involved in the transaction (known as extra transaction proof or anchor).

Third parties don't have this information. They only see that a UTXO has been spent. Confidentiality is therefore assured.

To clarify the structure, let's summarize the process in two transactions:

- Transaction 1: This contains the seal definition, i.e. the outpoint that will serve as the seal.

- Transaction 2: Spends this outpoint. This closes the seal and, in the same transaction, inserts the commitment on the message.

We therefore call the second transaction the "witness transaction".

To illustrate this from another angle, we can represent two layers:

- The top layer (blockchain, public): everyone sees the transaction and knows that a outpoint has been spent;

- The lower layer (client-side, private): only Alice (or the person concerned) knows that this expense corresponds to such and such a message, via the cryptographic proof and the message she keeps locally.

But when closing the seal, the question arises as to where the commitment should be inserted.

In the previous section, we briefly mentioned how the Client-side Validation model can be applied to RGB and other systems. Here, we tackle the part about deterministic Bitcoin commitments and how to integrate them into a transaction. The idea is to understand why we are trying to insert a single commitment into the witness transaction, and above all how to ensure that there can be no other undisclosed competing commitments.

Commitment locations in a transaction

When you give someone proof that a certain message is embedded in a transaction, you need to be able to guarantee that there isn't another form of commitment (a second, hidden message) in the same transaction that hasn't been revealed to you. For client-side validation to remain robust, you need a deterministic mechanism for placing a single commitment in the transaction that closes the single-use seal.

The witness transaction spends the famous UTXO (or seal definition) and this expenditure corresponds to the closing of the seal. Technically speaking, we know that each outpoint can only be spent once. This is precisely what underpins Bitcoin's resistance to double spending. But the spending transaction may have several inputs, several outputs, or be composed in a complex way (coinjoins, Lightning channels, etc.). We therefore need to clearly define where to insert the commitment in this structure, unambiguously and uniformly.

Whatever the method (PkO, TxO2, etc.), the commitment can be inserted:

- In an Input via:

- Sigtweak (modifies the

rcomponent of the ECDSA signature, similar to the "Sign-to-contract" principle); - Witweak (the transaction's segregated witness data is modified).

- Sigtweak (modifies the

- In an Output via:

- Keytweak (the recipient's public key is "tweaked" with the message);

- Opret (the message is placed in a non-spendable

output

OP_RETURN); - Tapret (or Taptweak), which relies on taproot to insert commitment into the script part of a taproot key, thus modifying the public key deterministically.

Here are the details of each method:

Sig tweak (sign-to-contract):

An earlier scheme involved exploiting the random part of a signature (ECDSA or Schnorr) to embed the commitment: this is the technique known as "Sign-to-contract". You replace the randomly generated nonce with a hash containing the data. In this way, the signature implicitly reveals your commitment, without any additional space in the transaction. This approach has a number of advantages:

- No on-chain overload (you use the same place as the basic nonce);

- In theory, this can be quite discrete, as the nonce is initially a random datum.

However, 2 major drawbacks have emerged:

- Multisig before Taproot: when you have several signatories, you need to decide which signature will carry the commitment. Signatures can be ordered differently, and if a signatory refuses, you lose control over the outcome of the commitment;

- MuSig and the shared nonce: with Schnorr multisig (MuSig), nonce generation is a multiparty algorithm, and it becomes virtually impossible to tweak the nonce individually.

In practice, sig tweak is also not very compatible with existing hardware (hardware wallets) and formats (Lightning, etc.). So this great idea is hard to put into practice.

Key tweak (pay-to-contract):

The key tweak takes up the historical concept of pay-to-contract. We take the public key X and tweak it

by adding the value H(message). Specifically, if X = x * G and h = H(message), then the new key will be X' = X + h * G. This tweaked key hides the commitment to the message. The holder of the original private key can, by adding h to his private key x, prove that he has the key to spend the

output. In theory, this is elegant, because:

- The commitment is entered without adding any additional fields;

- You don't store any additional on-chain data.

In practice, however, we come up against the following difficulties:

- Wallets no longer recognize the standard public key, since it has been "tweaked", so they can't easily associate UTXO with your usual key;

- Hardware wallets are not designed to sign with a key that is not derived from their standard derivation;

- You need to adapt your scripts, descriptors, etc.

In the context of RGB, this path was envisaged until 2021, but it proved too complicated to make it work with current standards and infrastructure.

Witness tweak:

Another idea, which certain protocols such as inscriptions Ordinals have put into practice, is to place the data directly in the witness section of the transaction (hence the expression "witness

tweak"). However, this method:

- Makes engagement immediately visible (you literally paste raw data into the witness);

- May be subject to censorship (miners or nodes may refuse to relay if it is too large or any other arbitrary characteristic);

- Consumes space in the blocks, contrary to RGB's objective of discretion and lightness.

In addition, witness is designed to be prunable in certain contexts, which can make having robust proofs more complicated.

Open-return (opret):

Very simple in its operation, an OP_RETURN allows you to store

a hash or message in a special field of the transaction. But it's

immediately detectable: everyone sees that there's a commitment in the

transaction, and it can be censored or discarded, as well as adding extra output.

Since this increases transparency and size, it's considered less satisfactory

from the point of view of a Client-side Validation solution.

34-byte_Opret_Commitment =

OP_RETURN OP_PUSHBYTE_32 <mpc::Commitment>

|_________| |______________| |_________________|

1-byte 1-byte 32 bytes

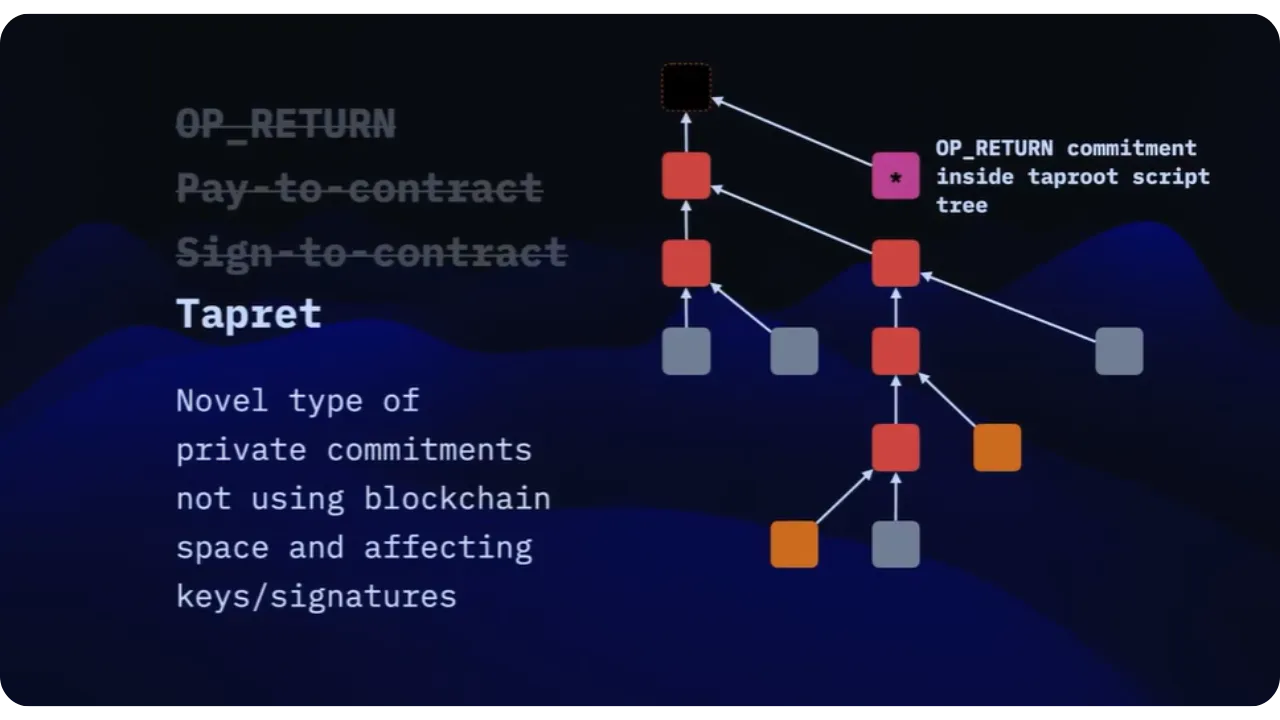

Tapret

The final option is the use of Taproot (introduced with

BIP341) with the Tapret scheme. Tapret is a more complex

form of deterministic commitment, which brings improvements in terms of

footprint on the blockchain and confidentiality for contract operations. The

main idea is to hide the commitment in the Script Path Spend part of a taproot transaction.

Before describing how the commitment is inserted into a taproot transaction, let's look at the exact form of the commitment, which must imperatively correspond to a 64-byte string constructed as follows:

64-byte_Tapret_Commitment =

OP_RESERVED ... ... .. OP_RESERVED OP_RETURN OP_PUSHBYTE_33 <mpc::Commitment> <Nonce>

|___________________________________| |_________| |______________| |_______________| |______|

OP_RESERVED x 29 times = 29 bytes 1 byte 1 byte 32 bytes 1 byte

|________________________________________________________________| |_________________________|

TAPRET_SCRIPT_COMMITMENT_PREFIX = 31 bytes MPC commitment + NONCE = 33 bytes

- The 29 bytes

OP_RESERVED, followed byOP_RETURN, thenOP_PUSHBYTE_33, form the 31-byte prefix part; - Next comes a 32-byte commitment (usually the Merkle root from MPC), to which we add 1 byte of Nonce (a total of 33 bytes for this second part).

So the 64-byte Tapret method looks like an Opret to which we've prefixed 29 bytes of OP_RESERVED and added an extra

byte as a Nonce.

To maintain flexibility in terms of implementation, confidentiality and scaling, the Tapret scheme takes into account various use cases, depending on requirements:

- Unique incorporation of a Tapret commitment into a taproot transaction without a pre-existing Script Path structure;

- Integration of a Tapret commitment into a Taproot transaction already equipped with a Script Path.

Let's take a closer look at each of these two scenarios.

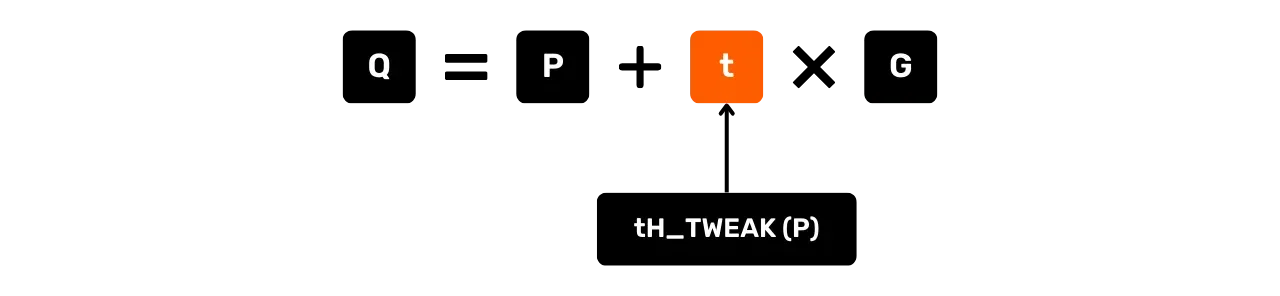

Tapret incorporation without existing Script Path

In this first case, we start from a taproot output key (Taproot Output Key) Q which contains only the internal public key P (Internal Key), with no associated script path (Script Path):

P: the internal public key for the Key Path Spend.G: the generating point of the elliptic curve secp256k1. -t = tH_TWEAK(P)is the tweak factor, calculated via a tagged hash (e.g.SHA-256(SHA-256(TapTweak) || P)), in accordance with BIP86. This proves that there is no hidden script.

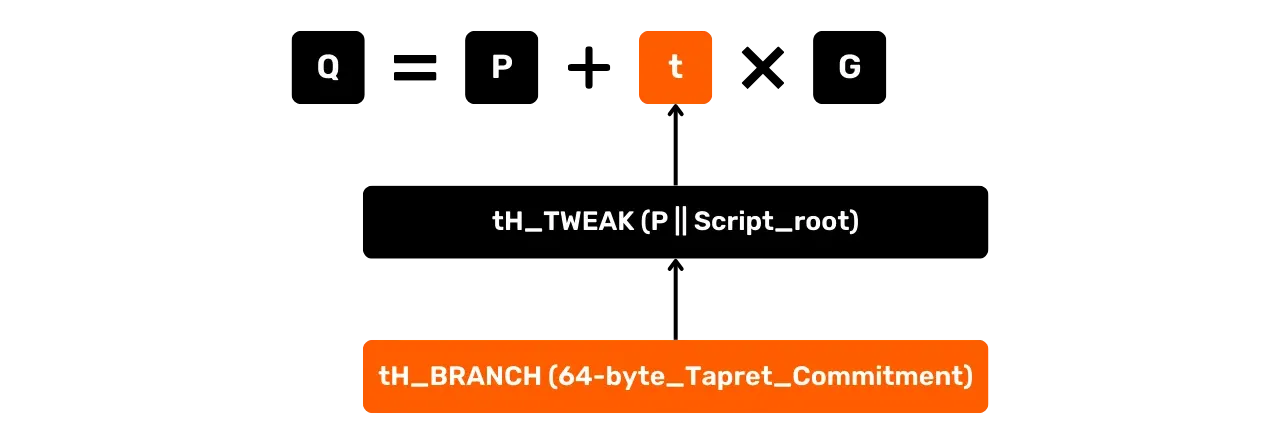

To include a Tapret commitment, add a Script Path Spend with a unique script, as follows:

t = tH_TWEAK(P || Script_root)then becomes the new tweak factor, including the Script_root.Script_root = tH_BRANCH(64-byte_Tapret_Commitment)represents the root of this script, which is simply a hash of typeSHA-256(SHA-256(TapBranch) || 64-byte_Tapret_Commitment).

The proof of inclusion and uniqueness in the taproot tree here boils down to

the single internal public key P.

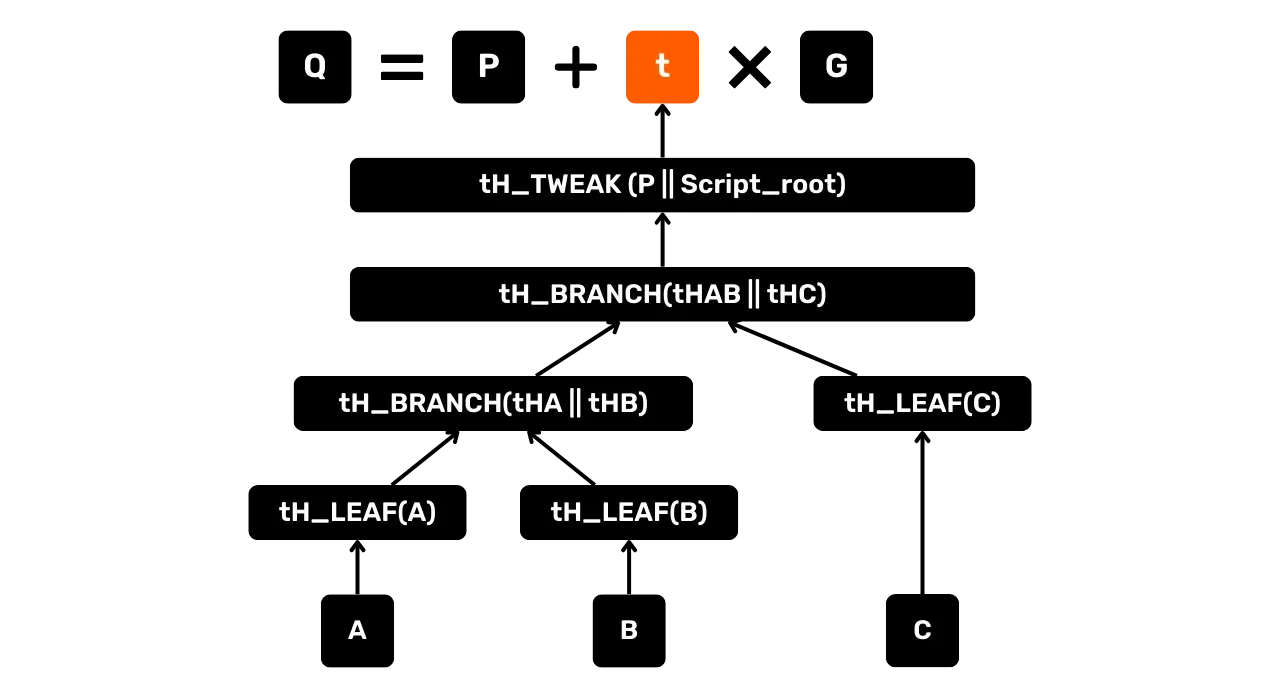

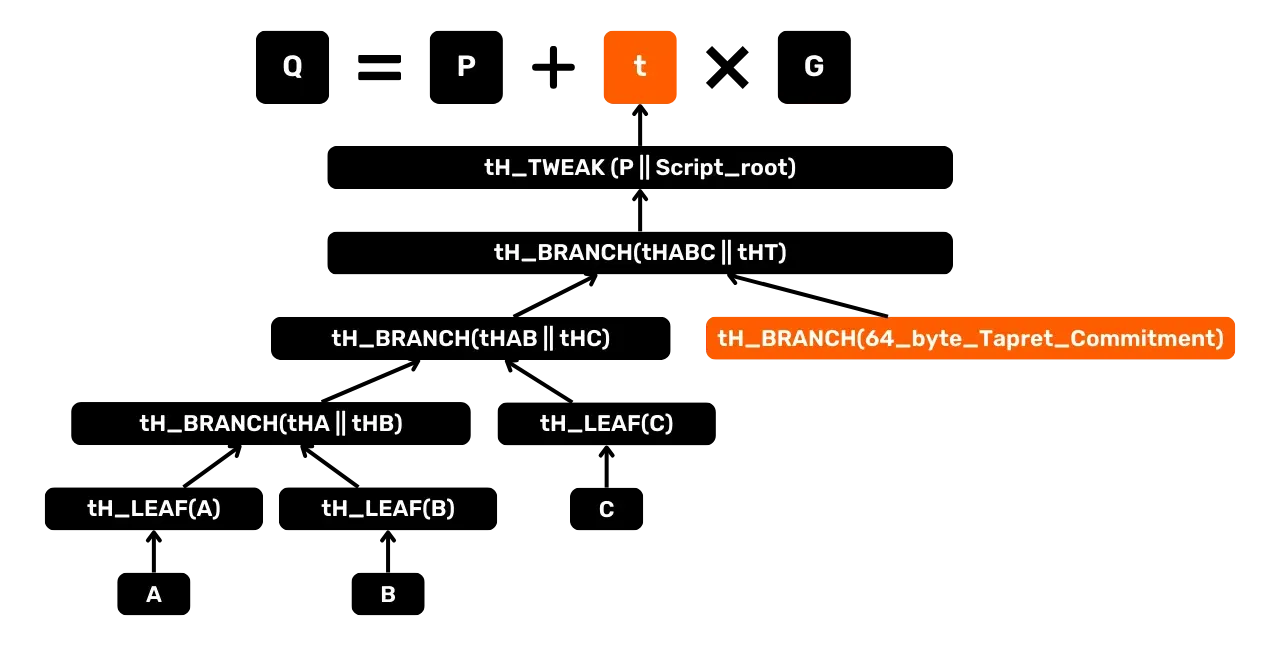

Tapret integration into a pre-existing Script Path

The second scenario concerns a more complex Q taproot output, which already contains several scripts. For

example, we have a tree of 3 scripts:

tH_LEAF(x)designates the normalized tagged hash function of a leaf script.A, B, Crepresent scripts already included in the taproot structure.

To add the Tapret commitment, we need to insert an unspendable script at the first level of the tree, shifting the existing scripts one level down. Visually, the tree becomes:

tHABCrepresents the tagged hash of the top level groupingA, B, C.tHTrepresents the hash of the script corresponding to the 64-byteTapret.

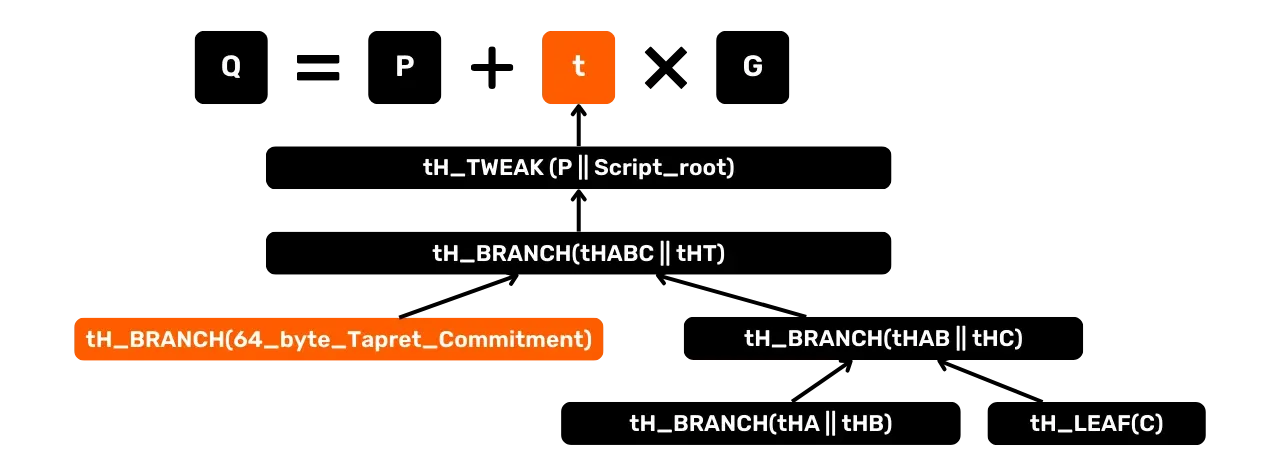

According to taproot rules, each branch/leaf must be combined according to a lexicographical hash order. There are two possible cases:

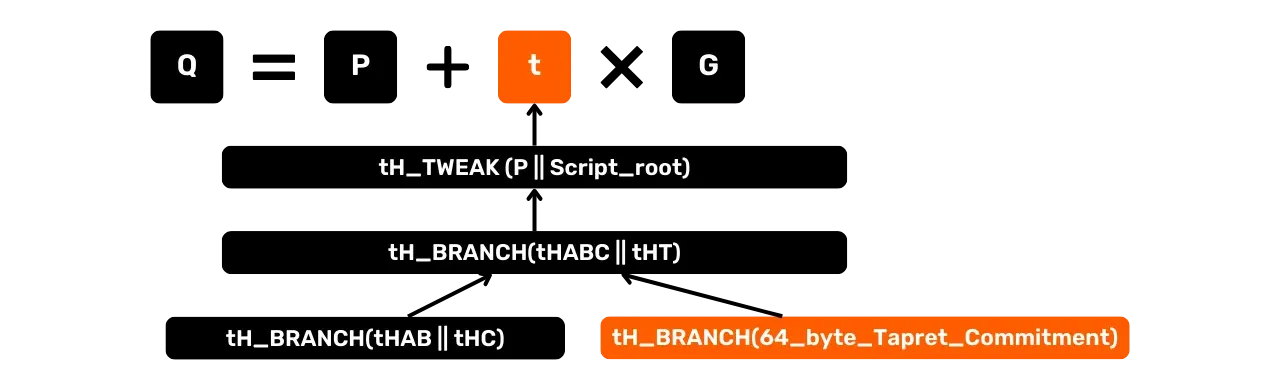

tHT>tHABC: the Tapret commitment moves to the right of the tree. The uniqueness proof only needstHABCandP;tHT<tHABC: the Tapret commitment is placed on the left. To prove that there is no other Tapret commitment on the right,tHABandtHCmust be revealed to demonstrate the absence of any other such script.

Visual example for the first case (tHABC < tHT):

Example for the second case (tHABC > tHT):

Optimization with the nonce

To improve confidentiality, we can "mine" (a more accurate term would be

"bruteforcing") the value of the <Nonce> (the last byte of

the 64-byte Tapret) in an attempt to obtain a hash tHT such that tHABC < tHT. In this case, the commitment is

placed on the right, saving the user from having to divulge the entire

contents of existing scripts to prove the Tapret's uniqueness.

In summary, the Tapret offers a discrete and deterministic way of

incorporating a commitment into a taproot transaction, while respecting the requirement

for uniqueness and unambiguity essential to RGB's Client-side Validation and

Single-use Seal logic.

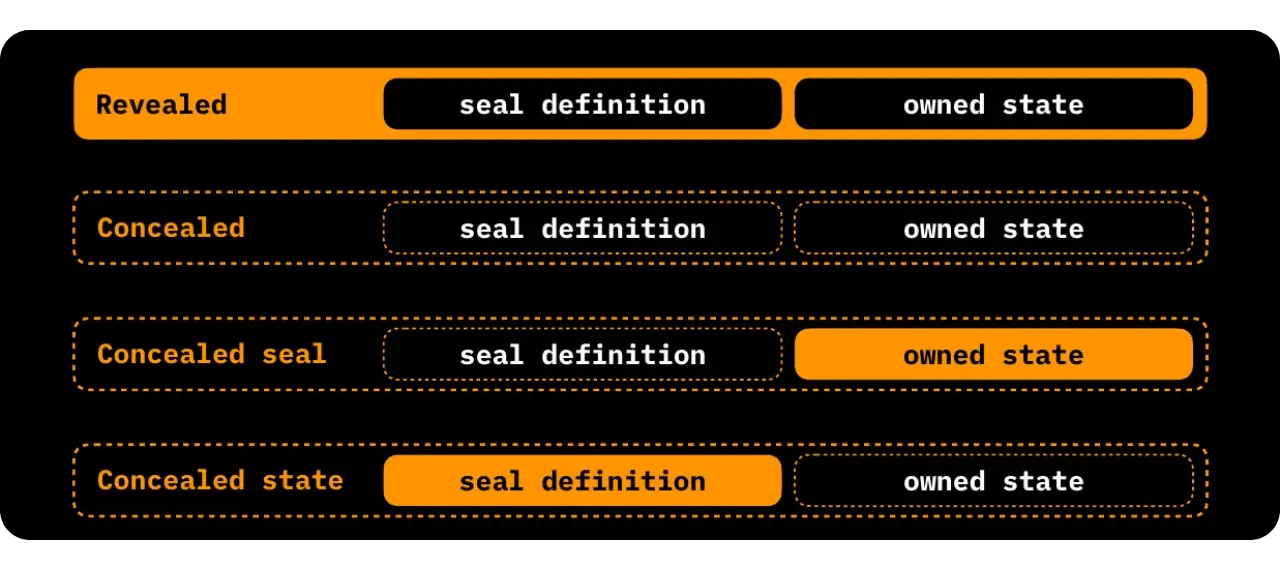

Valid exits

For RGB commitment transactions, the main requirement for a valid Bitcoin commitment scheme is as follows: The transaction (witness transaction) must provably contain a single commitment. This requirement makes it impossible to construct an alternative history for client-side validated data within the same transaction. This means that the message around which the single-use seal closes is unique.

To satisfy this principle, and regardless of the number of outputs in a transaction, we require that one and only one output can contain a commitment. For each of the schemes used (Opret or Tapret), the only valid outputs that can contain an RGB commitment are the following:

- The first output

OP_RETURN(if present) for the Opret scheme; - The first taproot output (if present) for the Tapret scheme.

Note that it is quite possible for a transaction to contain a single Opret commitment and a single Tapret commitment in two separate outputs.

Thanks to the deterministic nature of Seal Definition, these two commitments

then correspond to two distinct pieces of data validated on the client side.

Analysis and practical choices in RGB

When we started RGB, we reviewed all these methods to determine where and how to place a commitment in a transaction in a deterministic way. We defined some criteria:

- Compatibility with different scenarios (e.g. multisig, Lightning, hardware wallets, etc.);

- Impact on on-chain space;

- Difficulty of implementation and maintenance;

- Confidentiality and resistance to censorship.

| Method | On-chain trace & size | Client-side size | Wallet Integration | Hardware Compatibility | Lightning Compatibility | Taproot Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keytweak (deterministic P2C) | 🟢 | 🟡 | 🔴 | 🟠 | 🔴 BOLT, 🔴 Bifrost | 🟠 Taproot, 🟢 MuSig |

| Sigtweak (deterministic S2C) | 🟢 | 🟢 | 🟠 | 🔴 | 🔴 BOLT, 🔴 Bifrost | 🟠 Taproot, 🔴 MuSig |

| Opret (OP_RETURN) | 🔴 | 🟢 | 🟢 | 🟠 | 🔴 BOLT, 🟠 Bifrost | - |

| Tapret Algorithm: top-left node | 🟠 | 🔴 | 🟠 | 🟢 | 🔴 BOLT, 🟢 Bifrost | 🟢 Taproot, 🟢 MuSig |

| Tapret Algorithm #4: any node + proof | 🟢 | 🟠 | 🟠 | 🟢 | 🔴 BOLT, 🟢 Bifrost | 🟢 Taproot, 🟢 MuSig |

| Deterministic Commitment Scheme | Standard | On-Chain Cost | Proof Size on Client Side |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keytweak (Deterministic P2C) | LNPBP-1, 2 | 0 bytes | 33 bytes (non-tweaked key) |

| Sigtweak (Deterministic S2C) | WIP (LNPBP-39) | 0 bytes | 0 bytes |

| Opret (OP_RETURN) | - | 36 (v)bytes (additional TxOut) | 0 bytes |

| Tapret Algorithm: top-left node | LNPBP-6 | 32 bytes in the witness (8 vbytes) for any n-of-m multisig and spending through script path | 0 bytes on scriptless scripts taproot ~270 bytes in a single script case, ~128 bytes if multiple scripts |

| Tapret Algorithm #4: any node + uniqueness proof | LNPBP-6 | 32 bytes in the witness (8 vbytes) for single script cases, 0 bytes in the witness in most other cases | 0 bytes on scriptless scripts taproot, 65 bytes until the Taptree contains a dozen scripts |

| Layer | On-Chain Cost (Bytes/vbytes) | On-Chain Cost (Bytes/vbytes) | On-Chain Cost (Bytes/vbytes) | On-Chain Cost (Bytes/vbytes) | On-Chain Cost (Bytes/vbytes) | Client-Side Cost (Bytes) | Client-Side Cost (Bytes) | Client-Side Cost (Bytes) | Client-Side Cost (Bytes) | Client-Side Cost (Bytes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Tapret | Tapret #4 | Keytweak | Sigtweak | Opret | Tapret | Tapret #4 | Keytweak | Sigtweak | Opret |

| Single-sig | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0? | 0 |

| MuSig (n-of-n) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 32 | ? > 0 | 0 |

| Multi-sig 2-of-3 | 32/8 | 32/8 or 0 | 0 | n/a | 32 | ~270 | 65 | 32 | n/a | 0 |

| Multi-sig 3-of-5 | 32/8 | 32/8 or 0 | 0 | n/a | 32 | ~340 | 65 | 32 | n/a | 0 |

| Multi-sig 2-of-3 with timeouts | 32/8 | 0 | 0 | n/a | 32 | 64 | 65 | 32 | n/a | 0 |

| Layer | On-Chain Cost (vbytes) | On-Chain Cost (vbytes) | On-Chain Cost (vbytes) | Client-Side Cost (bytes) | Client-Side Cost (bytes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Base | Tapret #2 | Tapret #4 | Tapret #2 | Tapret #4 |

| MuSig (n-of-n) | 16.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FROST (n-of-m) | ? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multi_a (n-of-m) | 1+16n+8m | 8 | 8 | 33 * m | 65 |

| Branch MuSig / Multi_a (n-of-m) | 1+16n+8n+8xlog(n) | 8 | 0 | 64 | 65 |

| With timeouts (n-of-m) | 1+16n+8n+8xlog(n) | 8 | 0 | 64 | 65 |

| Method | Privacy & Scalability | Interoperability | Compatibility | Portability | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keytweak (Deterministic P2C) | 🟢 | 🔴 | 🔴 | 🟡 | 🟡 |

| Sigtweak (Deterministic S2C) | 🟢 | 🔴 | 🔴 | 🟢 | 🔴 |

| Opret (OP_RETURN) | 🔴 | 🟠 | 🔴 | 🟢 | 🟢 |

| Algo Tapret: Top-left node | 🟠 | 🟢 | 🟢 | 🔴 | 🟠 |

| Algo Tapret #4: Any node + proof | 🟢 | 🟢 | 🟢 | 🟠 | 🔴 |

In the course of the study, it became clear that none of the commitment schemes was fully compatible with the current Lightning standard (which does not employ Taproot, muSig2 or additional commitment support). Efforts are underway to modify Lightning's channel construction (BiFrost) to allow the insertion of RGB commitments. This is another area where we need to review the transaction structure, the keys and the way in which channel updates are signed.

The analysis showed that, in fact, other methods (key tweak, sig tweak, witness tweak, etc.) presented other forms of complication:

- Either we have a large on-chain volume;

- Either there is a radical incompatibility with the existing wallet code;

- Either the solution is not viable in non-cooperative multisig.

For RGB, two methods in particular stand out: Opret and Tapret, both classified as "Transaction Output", and compatible with the TxO2 mode used by the protocol.

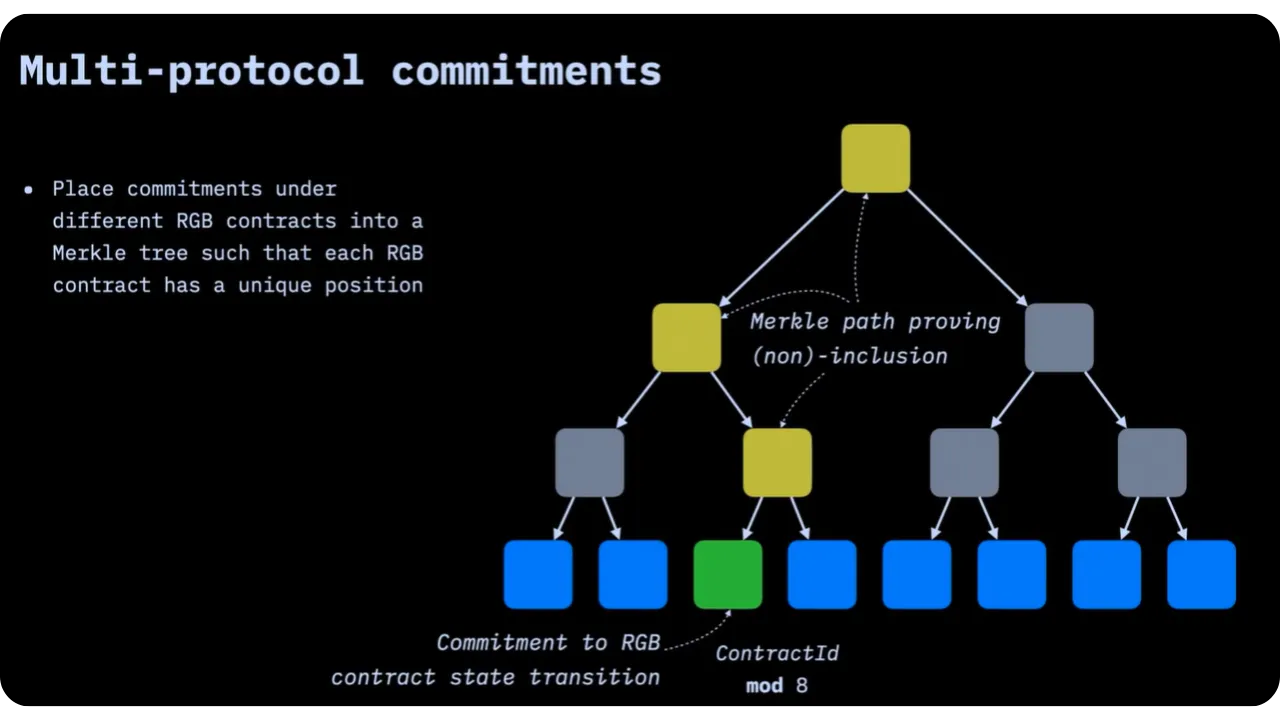

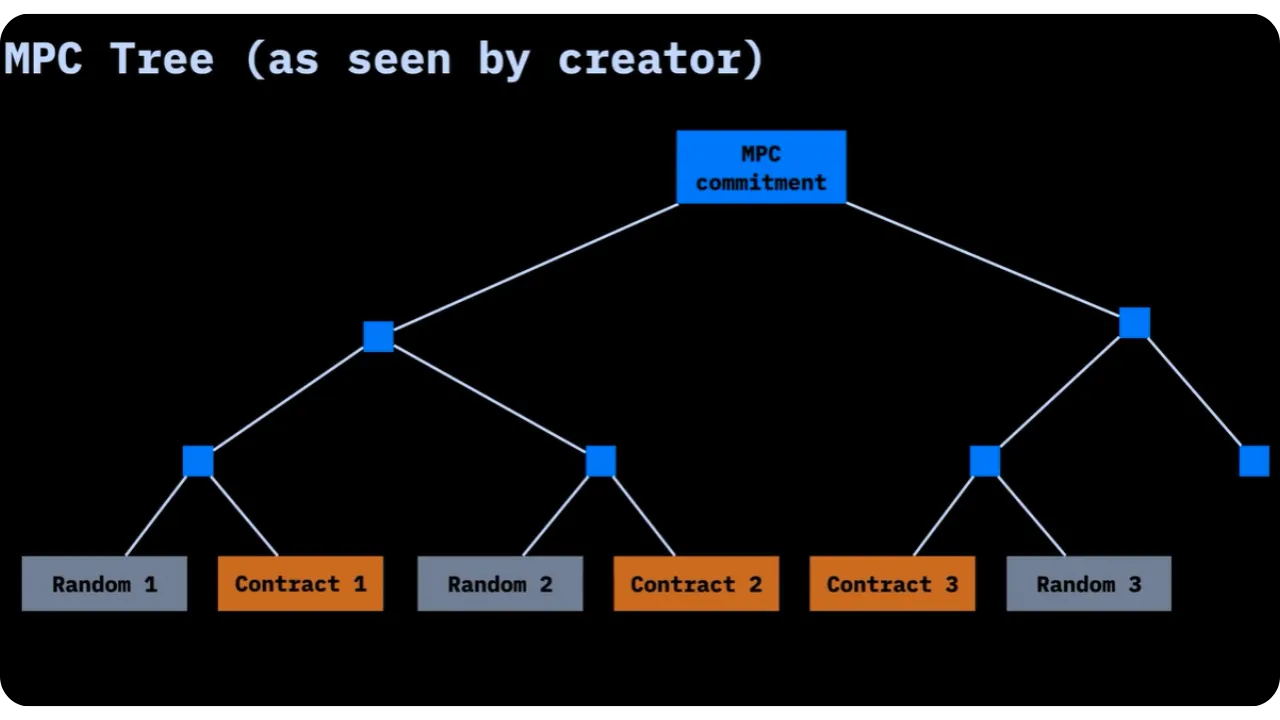

Multi Protocol Commitments - MPC

In this section, we look at how RGB handles the aggregation

of multiple contracts (or, more precisely, their transition bundles) within a single commitment (commitment) recorded in a Bitcoin transaction via a deterministic scheme (according

to Opret or Tapret). To achieve this, the order of

Merkelization of the various contracts takes place in a structure called MPC Tree (Multi Protocol Commitment Tree). In this section, we'll look at

the construction of this MPC Tree, how to obtain its root, and how multiple

contracts can share the same transaction confidentially and unambiguously.

Multi Protocol Commitment (MPC) is designed to meet two needs:

- The construction of the

mpc::Commitmenthash: this will be included in the Bitcoin blockchain according to anOpretorTapretscheme, and must reflect all the state changes to be validated; - Simultaneous storage of multiple contracts in a single commitment, enabling separate updates on multiple assets or RGB contracts to be managed in a single Bitcoin transaction.

In concrete terms, each transition bundle belongs to a particular

contract. All this information is inserted into a MPC Tree,

whose root (mpc::Root) is then hashed again to give the mpc::Commitment. It is this last hash that is placed in the

Bitcoin transaction (witness transaction), according to the

deterministic method chosen.

MPC Root Hash

The value actually written on-chain (in Opret or Tapret) is called mpc::Commitment. This is

calculated in the form of BIP-341, according to the formula:

mpc::Commitment = SHA-256(SHA-256(mpc_tag) || SHA-256(mpc_tag) || depth || cofactor || mpc::Root )

where:

mpc_tagis a tag:urn:ubideco:mpc:commitment#2024-01-31, chosen according to RGB tagging conventions;depth(1 byte) indicates the depth of the MPC Tree;- cofactor` (16 bits, in Little Endian) is a parameter used to promote the uniqueness of the positions assigned to each contract in the tree;

mpc::Rootis the root of MPC Tree, calculated according to the process described in the next section.

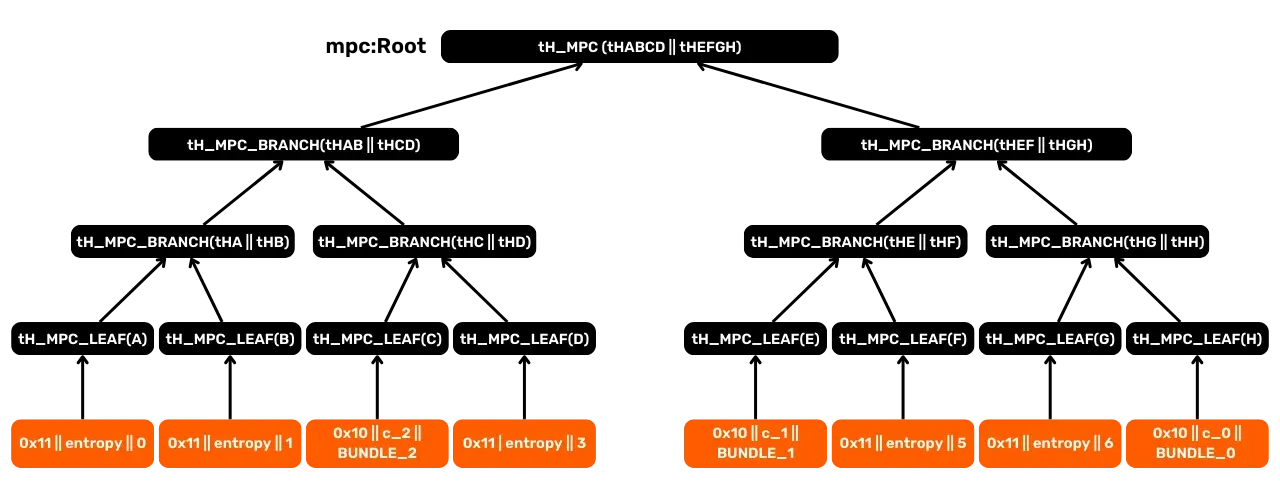

MPC Tree construction

To build this MPC Tree, we need to ensure that each contract corresponds to a unique leaf position. Suppose we have:

ccontracts to be included indexed byiini= {0,1,..,C-1};- For each contract

c_i, we have an identifierContractId(i) = c_i.

We then construct a tree of width w and depth d such that 2^d = w, with w > C, so that each

contract can be placed in a separate leaf. The position pos(c_i) of each contract in the tree is determined by:

pos(c_i) = c_i mod (w - cofactor)

where cofactor is an integer that increases the probability of obtaining

distinct positions for each contract. In practice, construction follows an iterative

process:

- We start from a minimum depth (

d=3by convention to hide the exact number of contracts); - We try different

cofactors(up tow/2, or a maximum of 500 for performance reasons); - If we fail to position all contracts without collision, we increment

dand start again.

The aim is to avoid trees that are too tall, while keeping the risk of collision to a minimum. Note that the collision phenomenon follows a random distribution logic, linked to the Anniversary Paradox.

Inhabited leaves

Once C distinct positions pos(c_i) have been

obtained for contracts i = {0,1,..,C-1}, each sheet

is filled with a hash function (tagged hash):

tH_MPC_LEAF(c_i) = SHA-256(SHA-256(merkle_tag) || SHA-256(merkle_tag) || 0x10 || c_i || BundleId(c_i))

where:

merkle_tag = urn:ubideco:merkle:node#2024-01-31, is always chosen according to the Merkle conventions of RGB;0x10identifies a contract leaf;c_iis the 32-byte contract identifier (derived from the Genesis hash);- bundleId(c_i)

is a 32-byte hash describing the set ofState Transitionsrelative toc_i` (gathered into a Transition Bundle).

Uninhabited leaves

The remaining leaves, not assigned to a contract (i.e. w - C leaves), are filled with a "dummy" value (entropy leaf):

tH_MPC_LEAF(j) = SHA-256(SHA-256(merkle_tag) || SHA-256(merkle_tag) || 0x11 || entropy || j )

where:

merkle_tag = urn:ubideco:merkle:node#2024-01-31, is always chosen according to the Merkle conventions of RGB;0x11denotes an entropy leaf;entropyis a random value of 64 bytes, chosen by the person building the tree;jis the position (in 32 bits Little Endian) of this leaf in the tree.

MPC nodes

After generating the w leaves (inhabited or not), we proceed to

merkelization. Any internal nodes are hashed as follows:

tH_MPC_BRANCH(tH1 || tH2) = SHA-256(SHA-256(merkle_tag) || SHA-256(merkle_tag) || b || d || w || tH1 || tH2)

where:

merkle_tag = urn:ubideco:merkle:node#2024-01-31, is always chosen according to the Merkle conventions of RGB;- b

is the _branching factor_ (8 bits). Most often,b=0x02` because the tree is binary and complete; - d` is the depth of the node in the tree;

wis the tree width (in 256-bit Little Endian binary);- tH1

andtH2` are the hashes of the child nodes (or leaves), already calculated as shown above.

Progressing in this way, we obtain the root mpc::Root. We can

then calculate mpc::Commitment (as explained above) and insert it

on-chain.

To illustrate this, let's imagine an example where C=3 (three

contracts). Their positions are assumed to be pos(c_0)=7, pos(c_1)=4, pos(c_2)=2. The other leaves

(positions 0, 1, 3, 5, 6) are entropy leaves. The diagram below

shows the sequence of hashes to the root with:

BUNDLE_iwhich representsBundleId(c_i);tH_MPC_LEAF(A)and so on, which represent leaves (some for contracts, others for entropy);- Each branch

tH_MPC_BRANCH(...)combines the hashes of its two children.

The final result is the mpc::Root, then the mpc::Commitment.

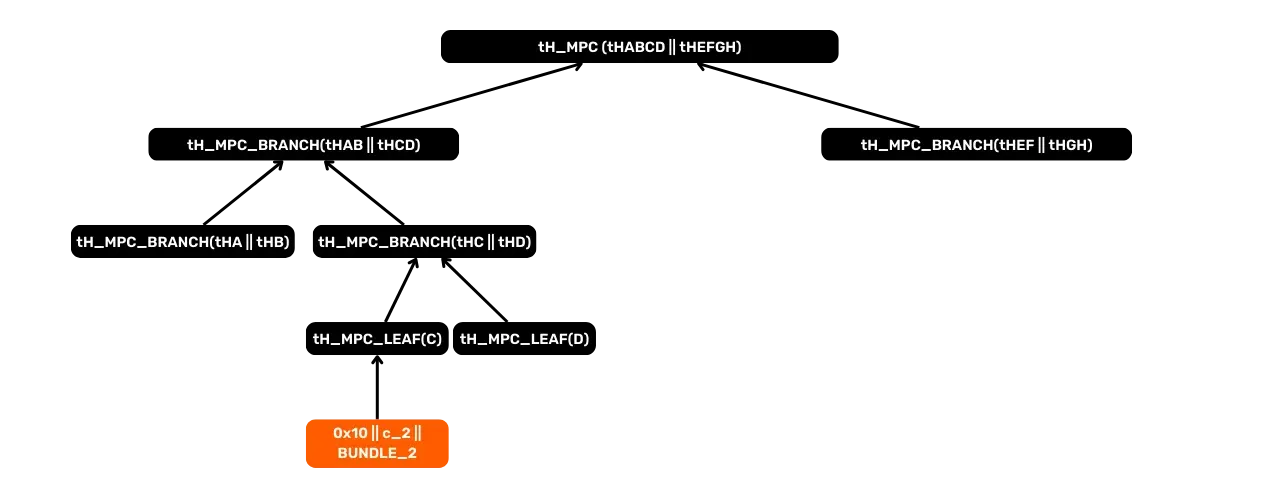

MPC shaft check

When a verifier wishes to ensure that a c_i contract (and its BundleId) is included in the final mpc::Commitment, he simply receives a Merkle proof. This proof

indicates the nodes needed to trace the leaves (in this case, c_i's contract leaf) back to the root. There's no need

to disclose the entire MPC Tree: this protects the confidentiality

of other contracts.

In the example, a c_2 verifier only needs an intermediate hash

(tH_MPC_LEAF(D)), two tH_MPC_BRANCH(...), the pos(c_2) position proof and the cofactor value. It can then locally

reconstruct the root, then recalculate the mpc::Commitment and

compare it to the one written in the Bitcoin transaction (within Opret or Tapret).

This mechanism ensures that:

- The status relative to

c_2is indeed included in the aggregate information block (client-side); - No one can build an alternative history with the same transaction, because the on-chain commitment points to a single MPC root.

Summary of the MPC structure

Multi Protocol Commitment* (MPC) is the principle that enables RGB to aggregate multiple contracts into a single Bitcoin transaction, while maintaining the uniqueness of commitments and confidentiality vis-à-vis other participants. Thanks to the deterministic construction of the tree, each contract is assigned a unique position, and the presence of "dummy" leaves (Entropy Leaves) partially masks the total number of contracts participating in the transaction.

The entire Merkle tree is never stored on the client. We simply generate a Merkle path for each contract concerned, to be transmitted to the recipient (who can then validate the commitment). In some cases, you may have several assets that have passed through the same UTXO. You can then merge several Merkle paths into a so-called multi-protocol commitment block, to avoid duplicating too much data.

Each Merkle proof is therefore lightweight, especially as the tree depth will not exceed 32 in RGB. There's also a notion of "Merkle block", which retains more information (cross-section, entropy, etc.), useful for combining or separating several branches.

That's why it took so long to finalize RGB. We had the overall vision from 2019: putting everything on client-side, circulating tokens off-chain. But for details like sharding for multiple contracts, the structure of the Merkle tree, how to handle collisions and merge proofs... all this required iterations.

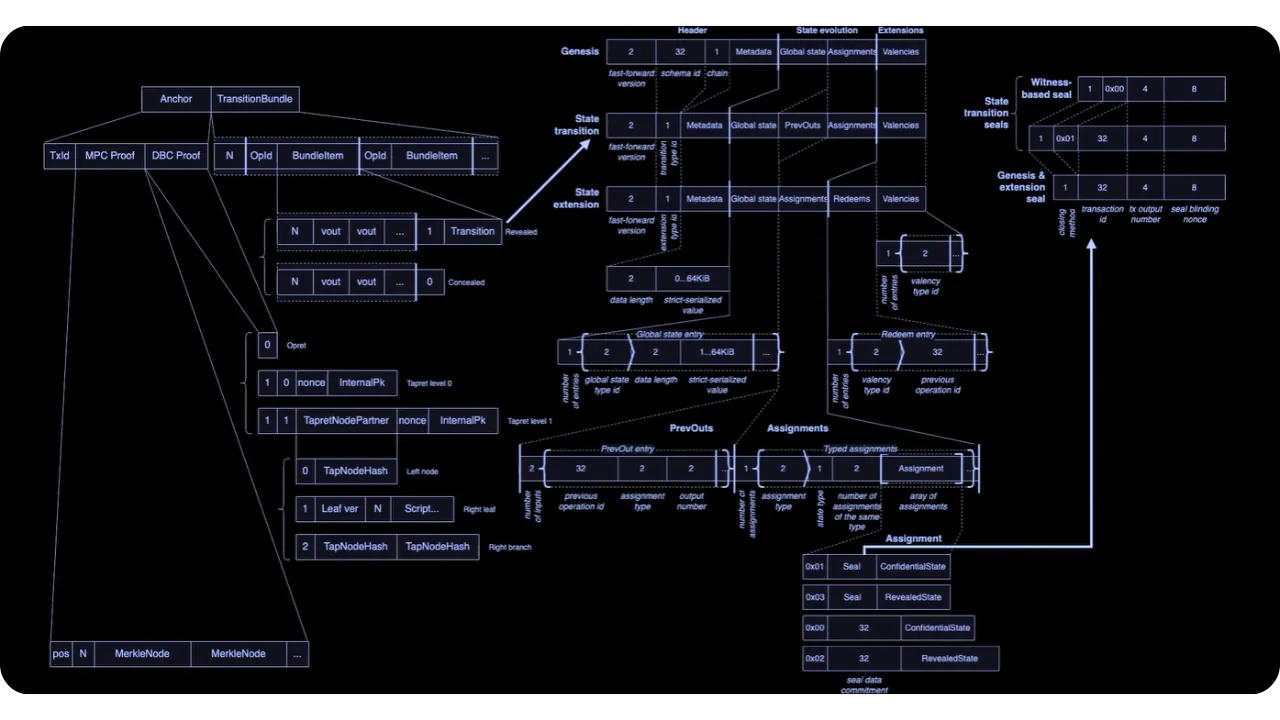

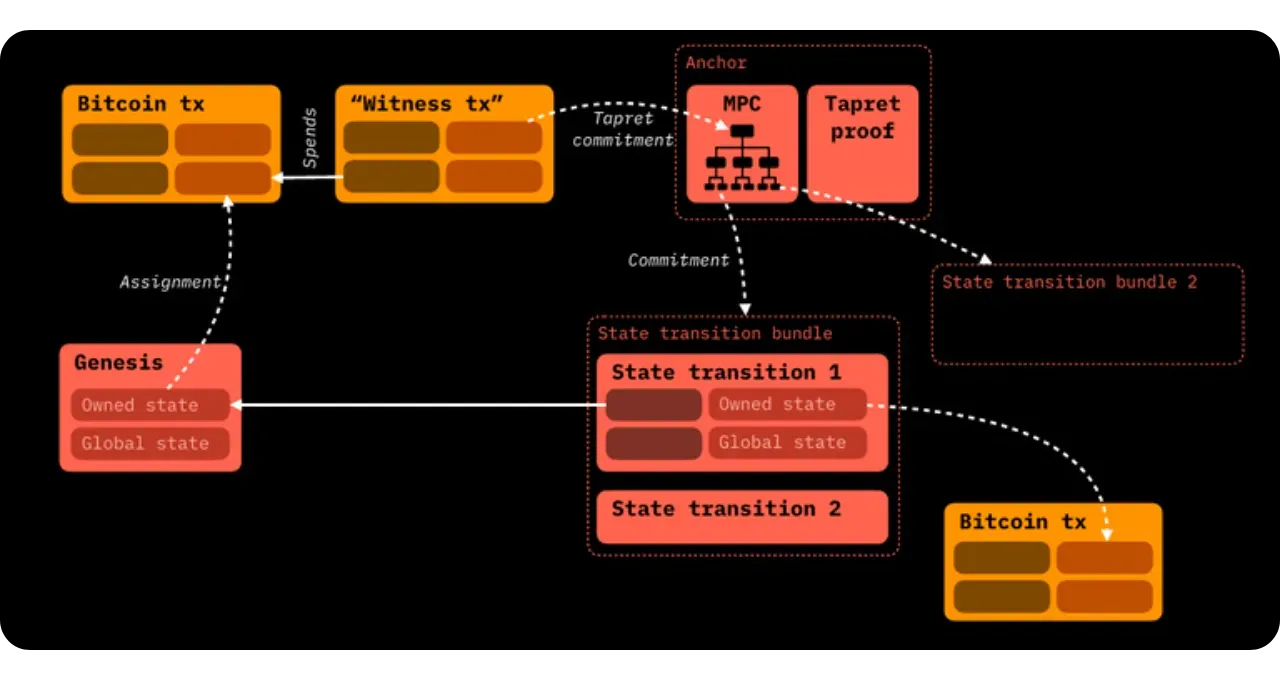

Anchors: a global assembly

Following on from the construction of our commitments (Opret or Tapret) and our MPC (Multi Protocol Commitment), we

need to address the notion of Anchor in the RGB protocol.

An Anchor is a client-side validated structure that brings together the

elements needed to verify that a Bitcoin commitment actually contains

specific contractual information. In other words, an Anchor summarizes all

the data needed to validate the commitments described above.

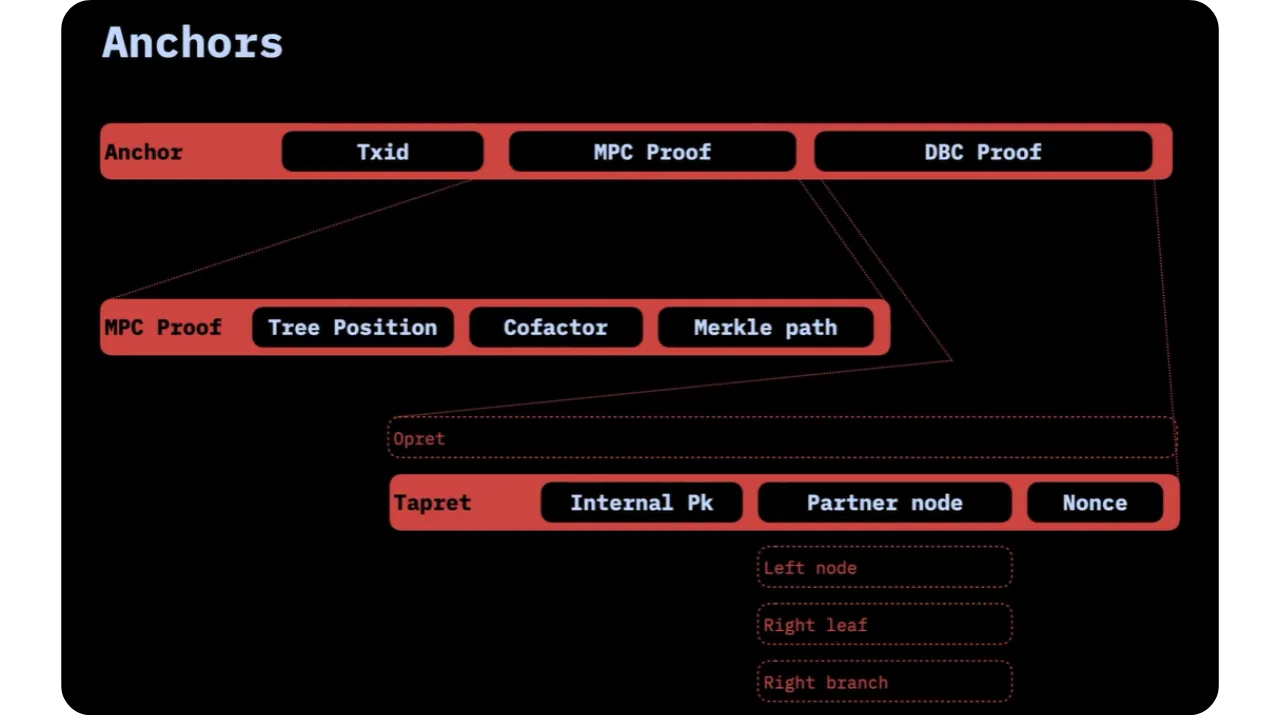

An Anchor consists of three ordered fields:

TxidMPC Proof- extra Transaction Proof - ETP

Each of these fields plays a part in the validation process, whether it's a

matter of reconstructing the underlying Bitcoin transaction or proving the

existence of a hidden commitment (particularly in the case of Tapret).

TxId

The Txid field corresponds to the 32-byte identifier of the

Bitcoin transaction containing the Opret or Tapret commitment.

In theory, it would be possible to find this Txid by tracing

the chain of state transitions which themselves point to each witness

transaction, following the logic of Single-use Seals. However, to facilitate

and accelerate verification, this Txid is simply included in the

Anchor, thus saving the validator from having to go back through the entire off-chain

history.

MPC Proof

The second field, MPC Proof, refers to the proof that this

particular contract (e.g. c_i) is included in the Multi Protocol Commitment. It is a combination of:

pos_i, the position of this contract in the MPC tree;- cofactor`, the value defined to resolve position collisions;

- the

Merkle Proof, i.e. the set of nodes and hashes used to reconstruct the MPC root and verify that the contract identifier and itsTransition Bundleare committed to the root.

This mechanism was described in the previous section on building the MPC Tree, where each contract obtains a unique leaf thanks to:

pos(c_i) = c_i mod (w - cofactor)

Then, a deterministic merkelization scheme is used to aggregate all the

leaves (contracts + entropy). In the end, the MPC Proof allows

the root to be reconstructed locally and compared with the mpc::Commitment included on-chain.

Extra Transaction Proof - ETP

The third field, the ETP, depends on the type of commitment

used. If the commitment is of type Opret, no additional proof

is required. The validator inspects the first OP_RETURN output

of the transaction and finds the mpc::Commitment directly there.

If the commitment is of type Tapret, an

additional proof called Extra Transaction Proof - ETP must be provided.

It contains:

- The internal public key (

P) of the taproot output in which the commitment is embedded; - The partner nodes of the

Script Path Spend(when the Tapret commitment is inserted in a script), in order to prove the exact location of this script in the taproot tree: - If the

Tapretcommitment is on the right-hand branch, we reveal the left-hand node (e.g.tHABC), - If the

Tapretcommitment is on the left, you need to disclose 2 nodes (e.g.tHABandtHC) to prove that no other commitment is present on the right-hand side. - The

noncemay be used to "mine" the best configuration, allowing the commitment to be placed on the right of the tree (proof optimization).

This additional proof is essential because, unlike Opret, the Tapret commitment is integrated into the structure of a taproot script, which

requires revealing part of the taproot tree in order to correctly validate

the location of the commitment.

The Anchors therefore encapsulate all the information

required to validate a Bitcoin commitment in the context of RGB. They

indicate both the relevant transaction (Txid) and the proof of

contract positioning (MPC Proof), while managing the additional

proof (ETP) in the case of Tapret. In this way, an

Anchor protects the integrity and uniqueness of the off-chain state by

ensuring that the same transaction cannot be reinterpreted for other

contractual data.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we covered:

- How to apply the Single-use Seals concept in Bitcoin (in particular via a outpoint);

- The various methods for deterministically inserting a commitment into a transaction (Sig tweak, Key tweak, witness tweak, op_return, Taproot/Tapret);

- The reasons why RGB focuses on Tapret commitments;

- Multi-contract management via multi-protocol commitments, essential if you don't want to expose an entire state or other contracts when you want to prove a specific point;

- We've also seen the role of Anchors, which bring everything together (transaction TXID, Merkle tree proof and Taproot proof) in a single package.

In practice, the technical implementation is divided between several dedicated Rust crates (in client_side_validation, commit-verify, bp_core, etc.). The fundamental notions are there:

In the next chapter, we'll look at the purely off-chain component of RGB, namely contract logic. We'll see how RGB contracts, organized as partially replicated finite state machines, achieve much higher expressiveness than Bitcoin scripts, while preserving the confidentiality of their data.

Introduction to smart contracts and their states

In this and the next chapter, we'll look at the notion of smart contract within the RGB environment and explore the different ways in which these contracts can define and evolve their state. We'll see why the RGB architecture, using the ordered sequence of Single-use Seals, makes it possible to execute various types of Contract Operations in a scalable way and without going through a centralized registry. We'll also look at the fundamental role of Business Logic in framing the evolution of the contract state.

Smart contracts and digital bearer rights

RGB's aim is to provide an infrastructure for implementing smart contracts on Bitcoin. By "smart contract" we mean an agreement between several parties that is automatically and computationally enforced, without human intervention to enforce the clauses. In other words, the law of the contract is enforced by the software, not by a trusted third party.

This automation raises the question of decentralization: how can we free ourselves from a centralized registry (e.g. a central platform or database) to manage ownership and contract performance? The original idea, taken up by RGB, is to return to a mode of ownership known as "bearer instruments". Historically, certain securities (bonds, shares, etc.) were issued in bearer form, enabling anyone who physically possessed the document to enforce his or her rights.

RGB applies this concept to the digital world: rights (and obligations) are encapsulated in data that is manipulated off-chain, and the status of this data is validated by the participants themselves. This allows, a priori, a much greater degree of confidentiality and independence than that offered by other approaches based on public registers.

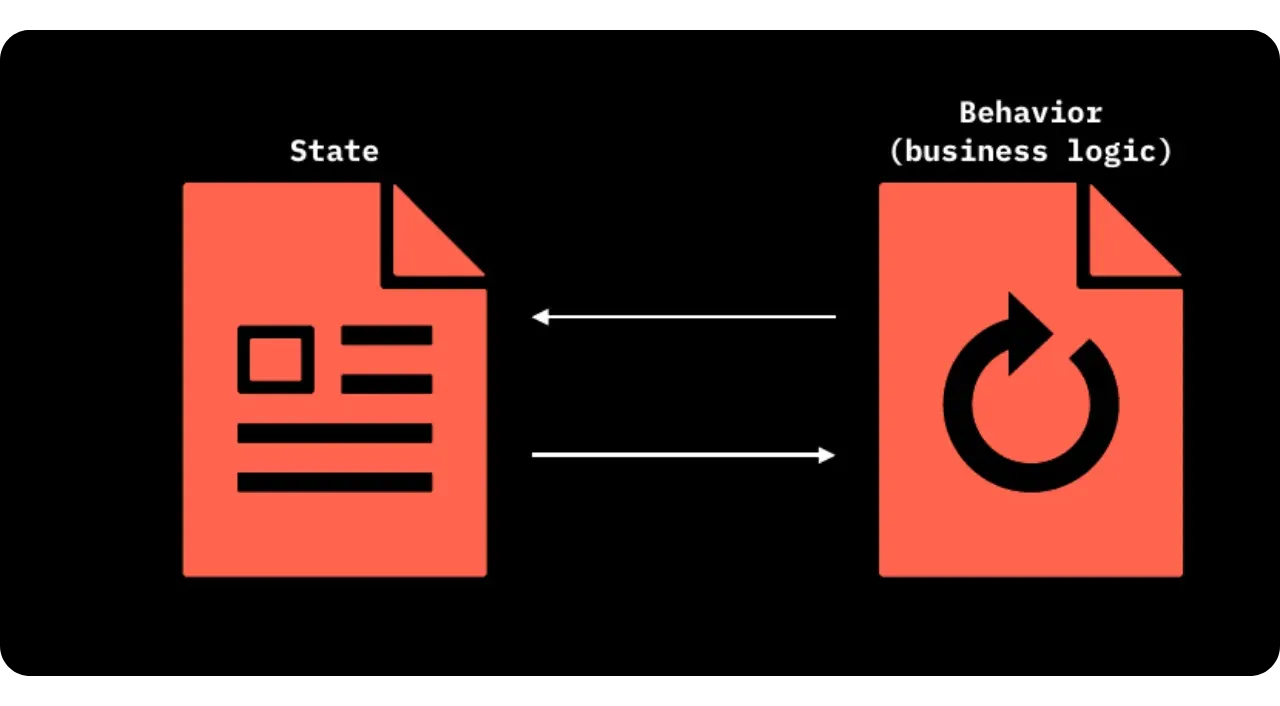

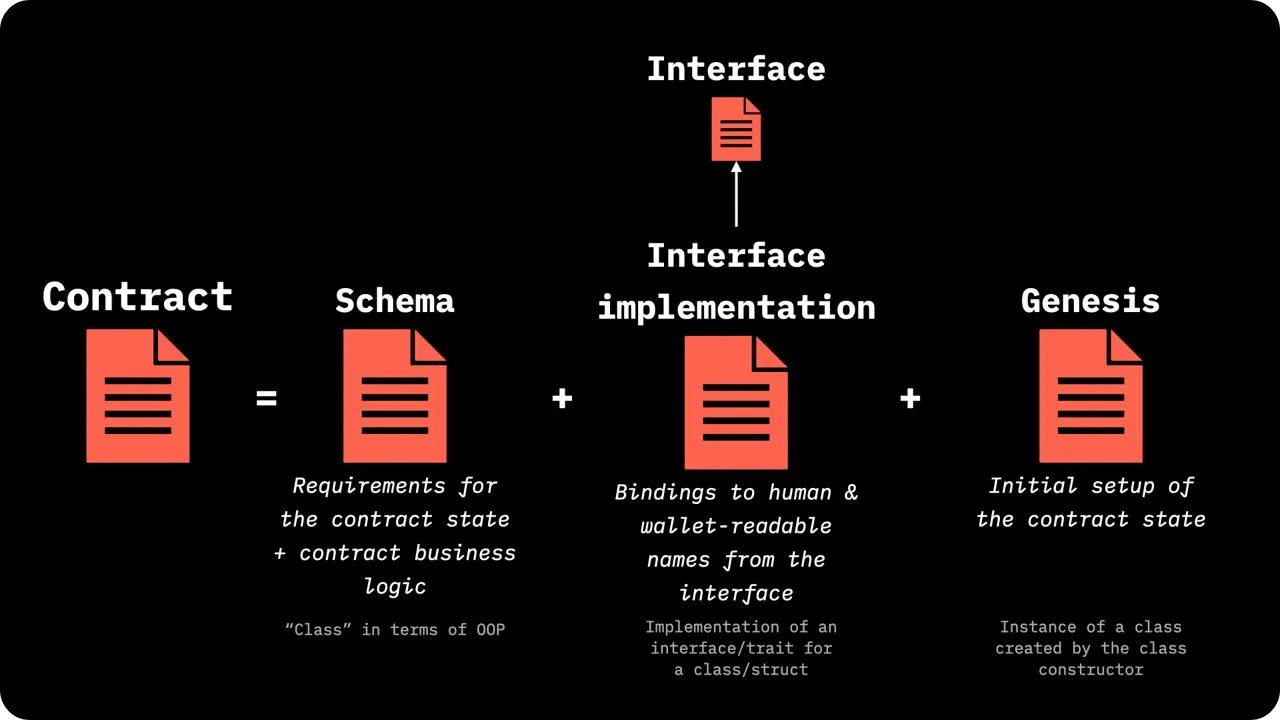

Introduction to Smart Contract RGB status

A smart contract in RGB can be seen as a state machine, defined by:

- A State, i.e. the set of information reflecting the current configuration of the contract;

- A Business Logic (set of rules), which describes under what conditions and by whom the state can be modified.

It's important to understand that these contracts are not limited to the simple transfer of tokens. They can embody a wide variety of applications: from traditional assets (tokens, stocks, bonds) to more complex mechanics (usage rights, commercial terms, etc.). Unlike other blockchains, where the contract code is accessible and executable by all, RGB's approach compartmentalizes access and knowledge of the contract to participants ("contract participants"). There are several roles:

- The issuer or creator of the contract, who defines the Genesis of the contract and its initial variables;

- Parties with rights (ownership) or other enforcement capabilities;

- Observers, potentially limited to seeing certain information, but who cannot trigger modifications.

This separation of roles contributes to censorship resistance, by ensuring that only authorized persons can interact with the contractual state. It also gives RGB the ability to scale horizontally: the majority of validations take place outside the blockchain, and only cryptographic anchors (the commitments) are inscribed on Bitcoin.

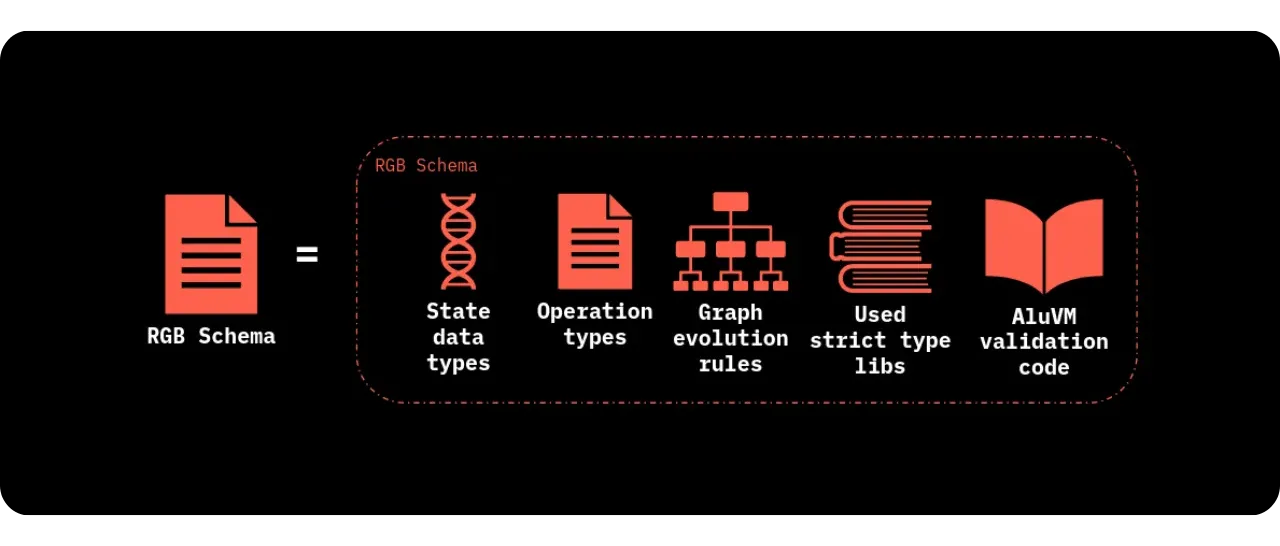

Status and Business Logic in RGB

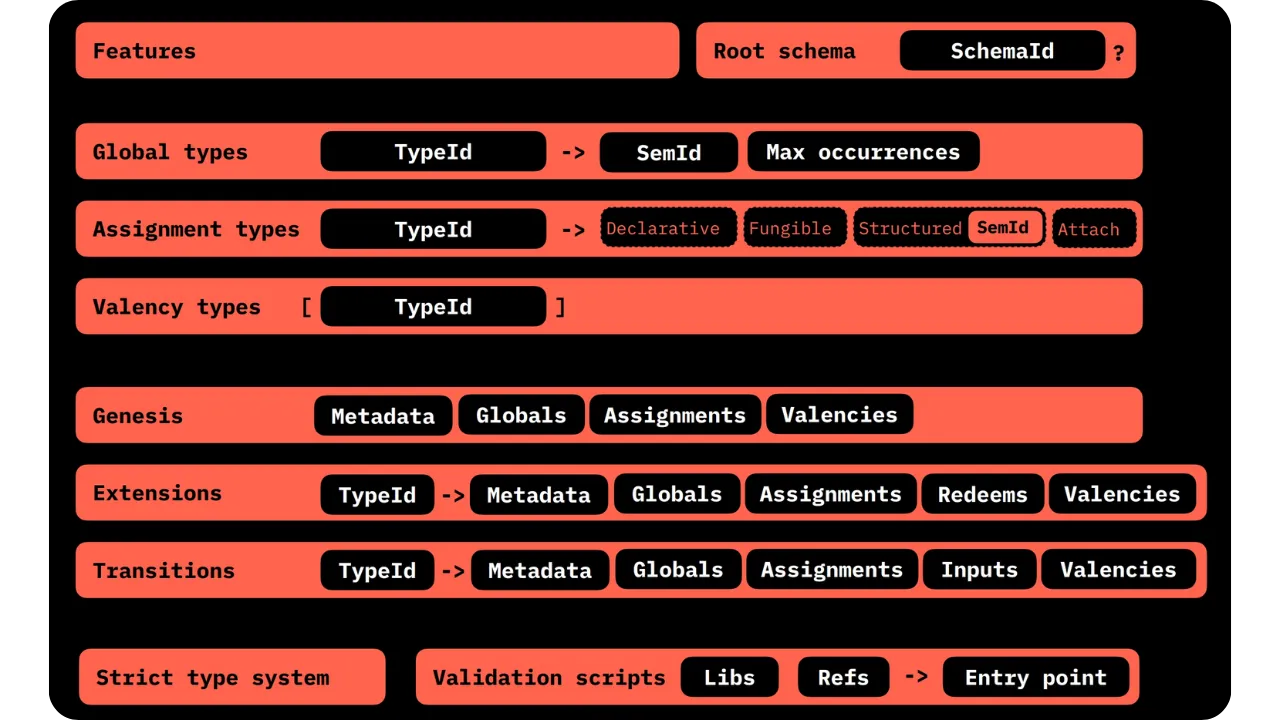

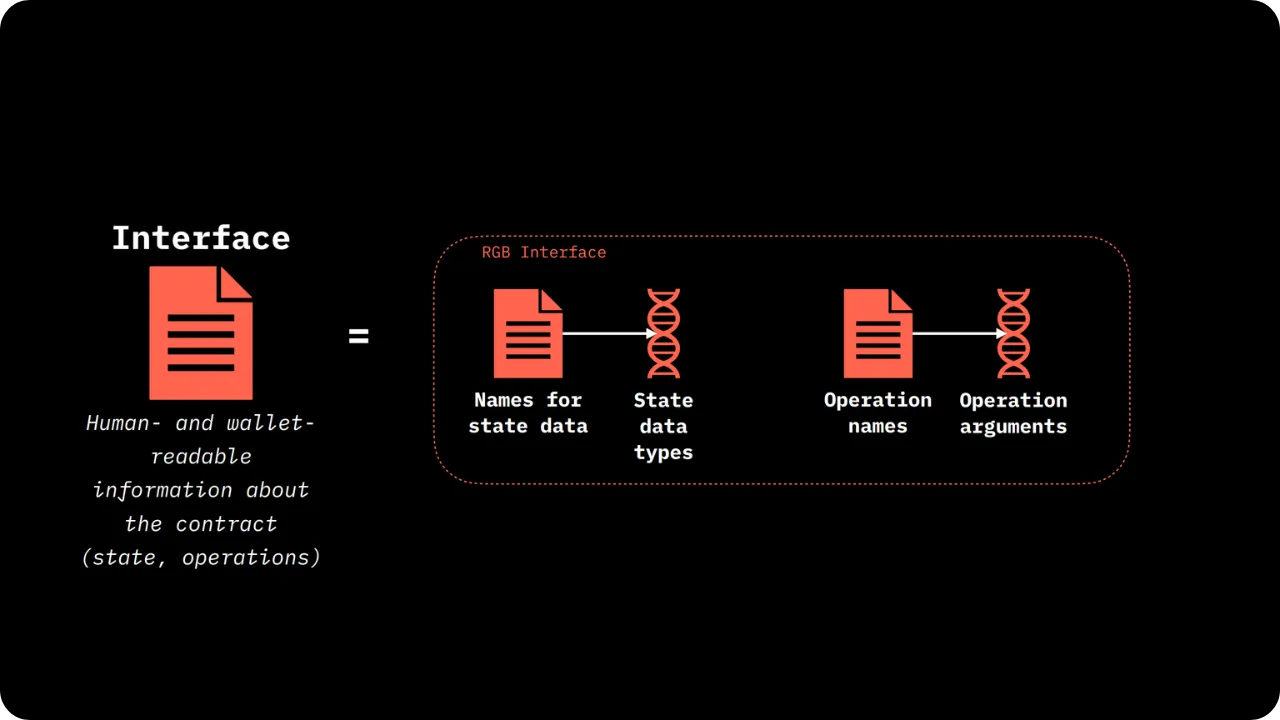

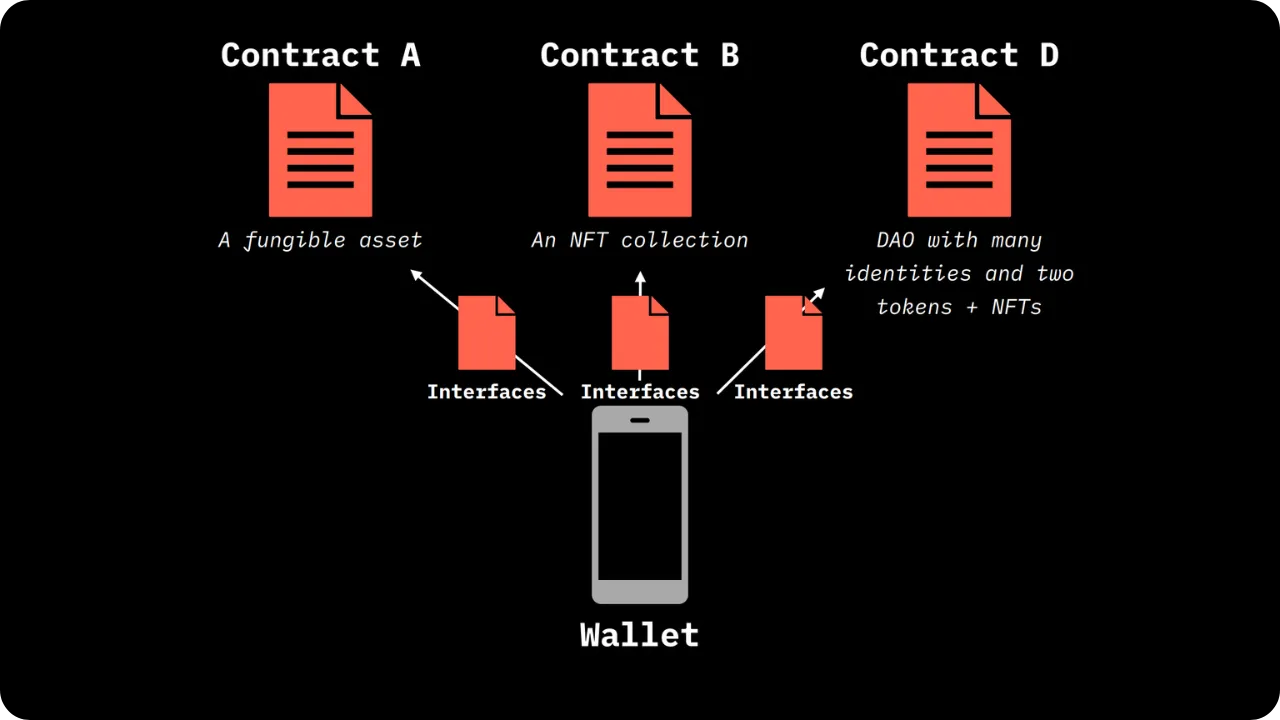

From a practical point of view, the contract's Business Logic takes the form of rules and scripts, defined in what RGB calls a Schema. The Schema encodes:

- State structure (which fields are public? Which fields are owned by which parties?

- Validity conditions (what must be checked before authorizing a state update?);

- Authorizations (who can initiate a State Transition? Who can only observe?).

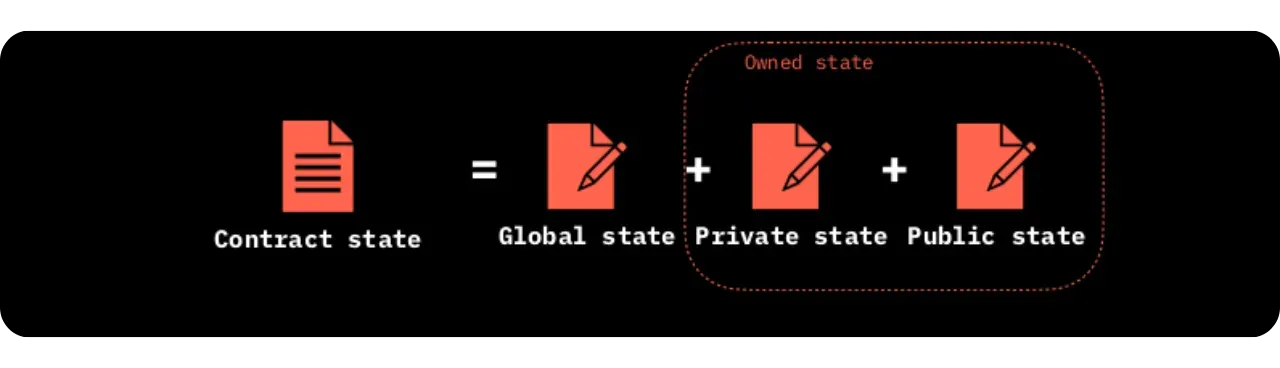

At the same time, the Contract State often breaks down into two components:

- A Global State: public part, potentially observable by all (depending on configuration);

- Owned States: private parts, allocated specifically to owners via UTXOs referenced in the contract logic.

As we'll see in the following chapters, any status update (Contract Operation) must dock to a Bitcoin commitment (via Opret or Tapret) and comply with the Business Logic scripts to be

considered valid.

Contract Operations: creation and evolution of the State

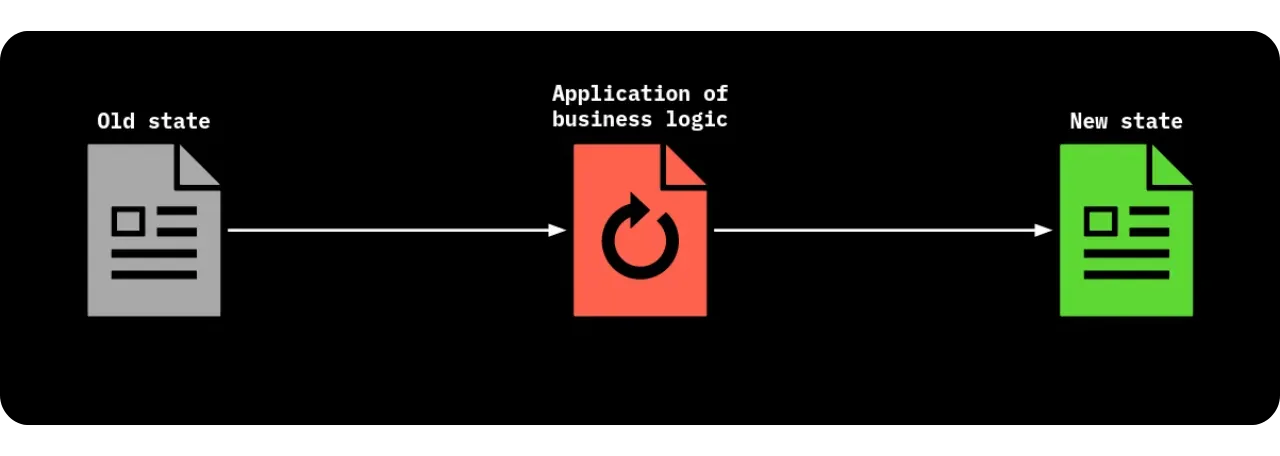

In the RGB universe, a Contract Operation is any event that changes the contract from a old state to a new state. These operations follow the following logic:

- We take note of the current status of the contract;

- We apply the rule or operation (a State Transition, a Genesis if it's the very first state, or a State Extension if there's a public valency to re-trigger);

- We anchor the modification via a new commitment on the blockchain, closing one single-use seal and creating another;

- The rights holders concerned validate locally (client-side) that the transition conforms to the Schema and that the associated Bitcoin transaction is registered on-chain.

The end result is an updated contract, now with a different state. This transition does not require the entire Bitcoin network to be concerned with the details, since only a small cryptographic fingerprint (the commitment) is recorded in the blockchain. The sequence of Single-use Seals prevents any double-spending or double-use of the State.

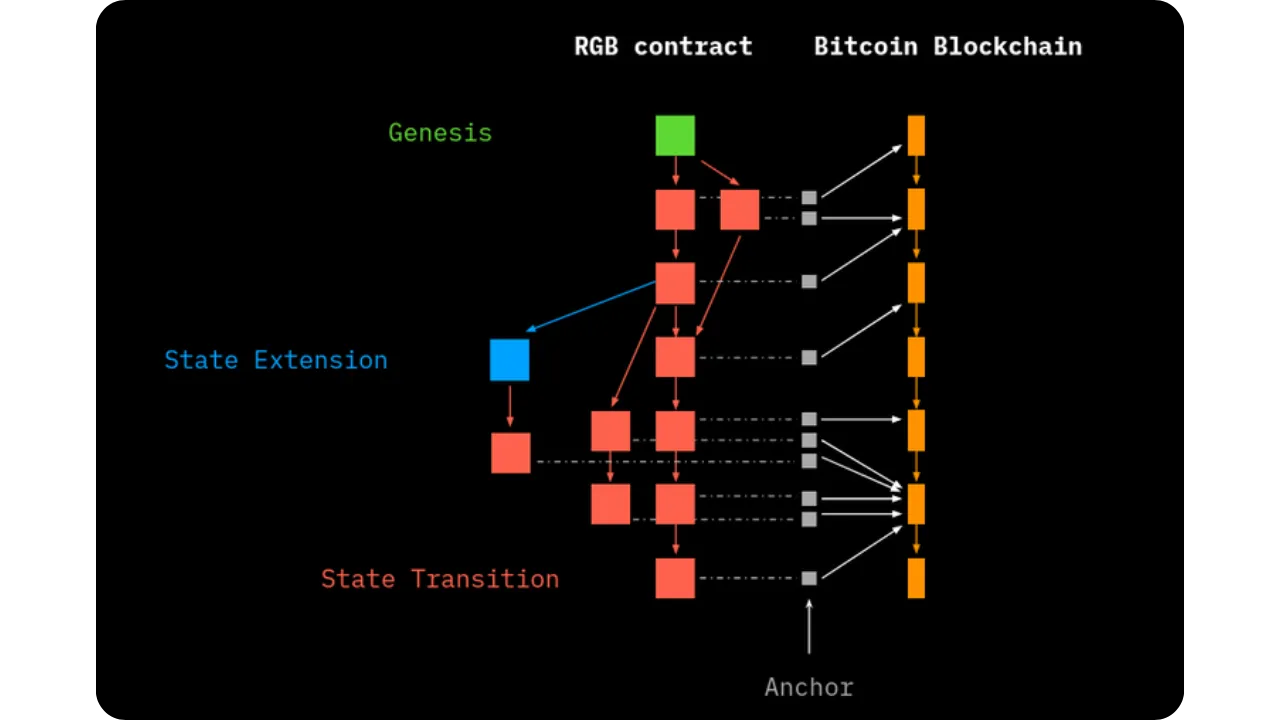

Operations chain: from Genesis to Terminal State

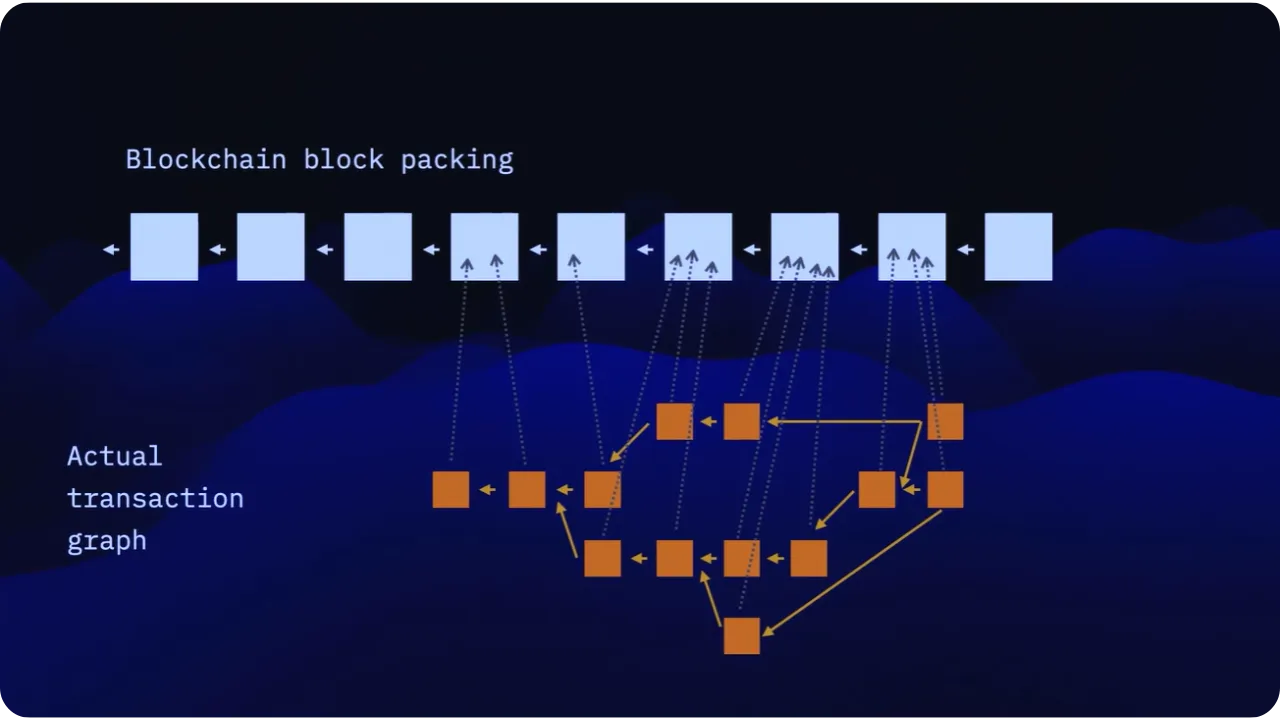

To put this into perspective, an RGB smart contract starts with a Genesis, the very first state. Thereafter, various Contract Operations follow one another, forming a DAG (Directed Acyclic Graph) of operations:

- Each transition is based on a previous state (or several, in the case of convergent transitions);

- The chronological order is guaranteed by the inclusion of each transition in a Bitcoin anchor, time-stamped and unalterable thanks to consensus by Proof-of-Work;

- When no more operations are in progress, a Terminal State is reached: the most recent and complete state of the contract.

This DAG topology (instead of a simple linear chain) reflects the possibility that different parts of the contract may evolve in parallel, as long as they do not contradict each other. RGB then takes care of avoiding any inconsistencies by client-side verification of each participant involved.

Summary

Smart contracts in RGB introduce a model of digital bearer instruments, decentralized but anchored in Bitcoin for time-stamping and guaranteeing the order of transactions. Automated execution of these contracts is based on:

- A Contract State, indicating the current configuration of the contract (rights, balances, variables, etc.);

- A Business Logic (Schema), defining which transitions are allowed and how they must be validated;

- Contract Operations, which update this state step by step, thanks to commitments anchored in Bitcoin transactions.

In the next chapter, we'll go into more detail about the concrete representation of these states and state transitions at the off-chain level, and how they relate to the UTXOs and Single-use Seals embedded in Bitcoin. This will be an opportunity to see how RGB's internal mechanics, based on client-side validation, manage to maintain the consistency of smart contracts while preserving data confidentiality.

RGB contract operations

In this chapter, we'll look at how operations in smart contracts and state transitions work, again within the RGB protocol. The aim will also be to understand how several participants cooperate to transfer ownership of an asset.

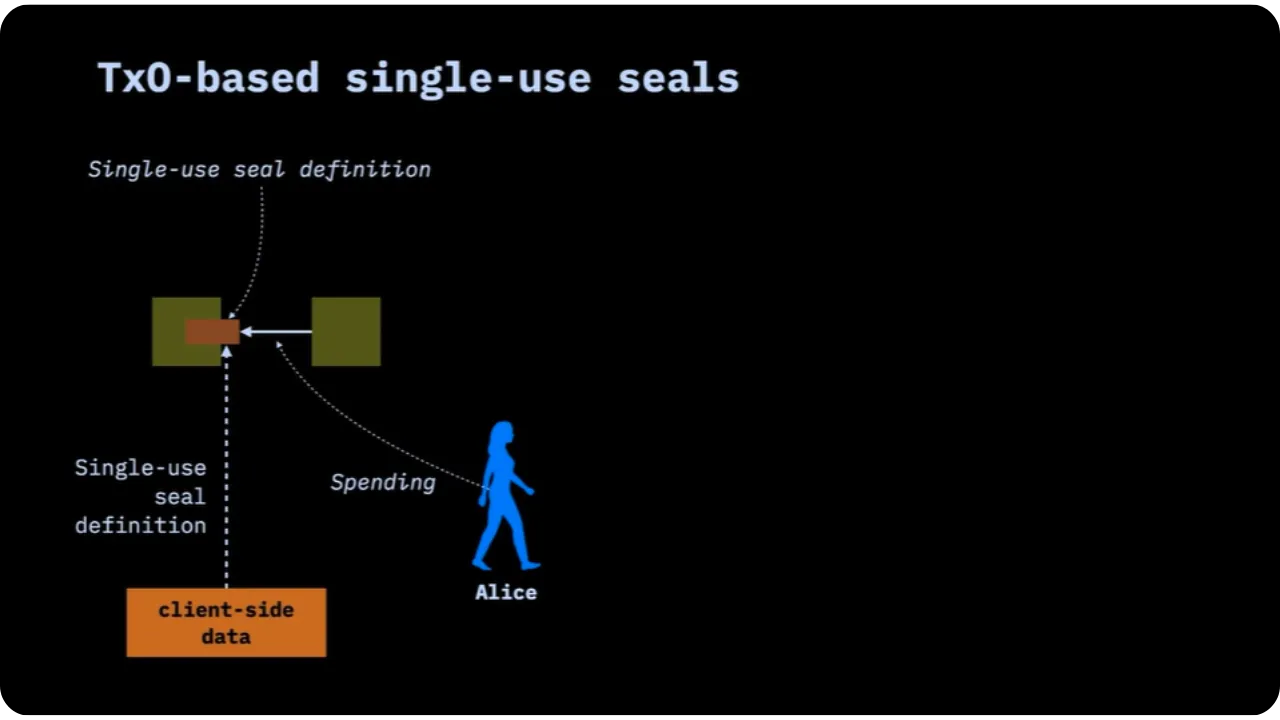

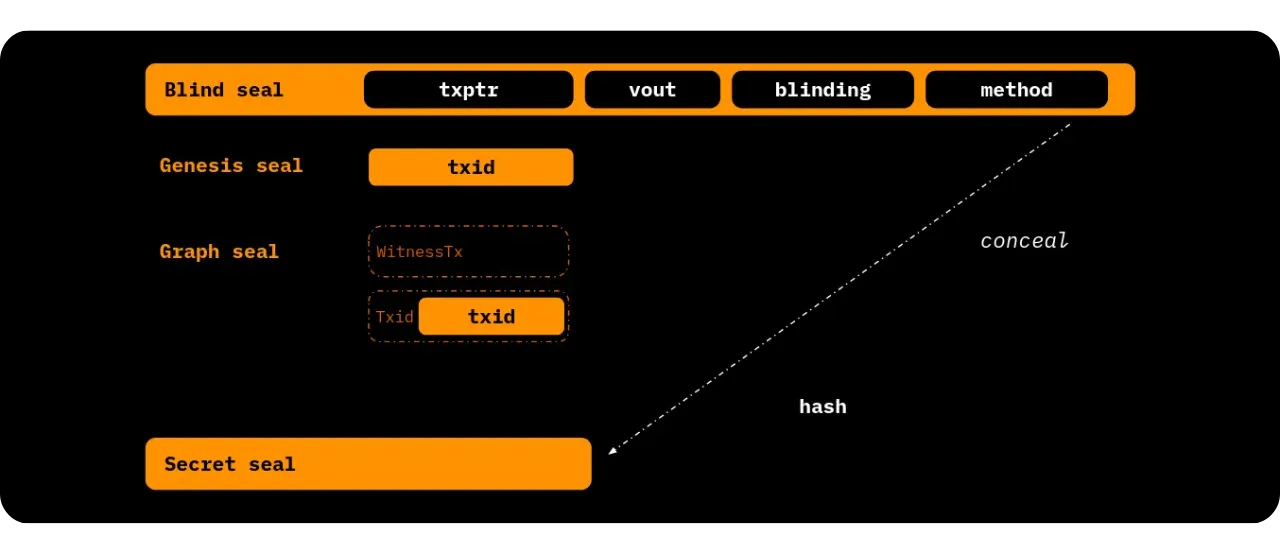

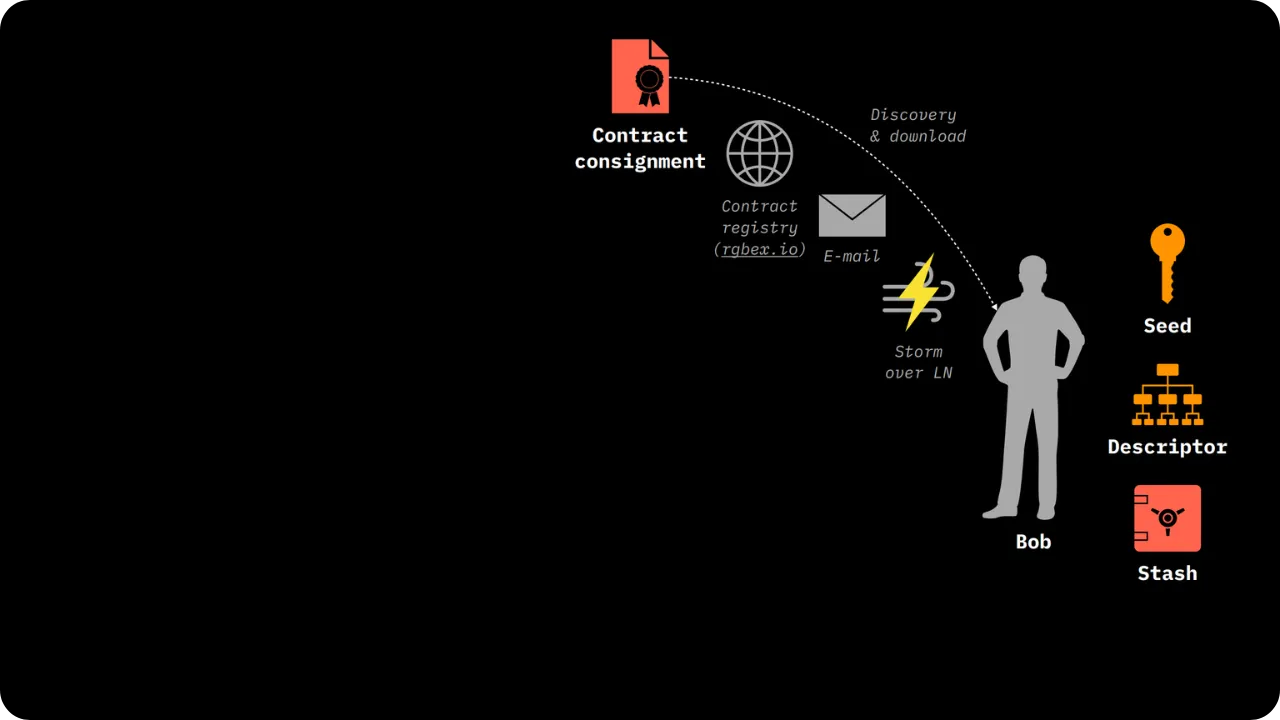

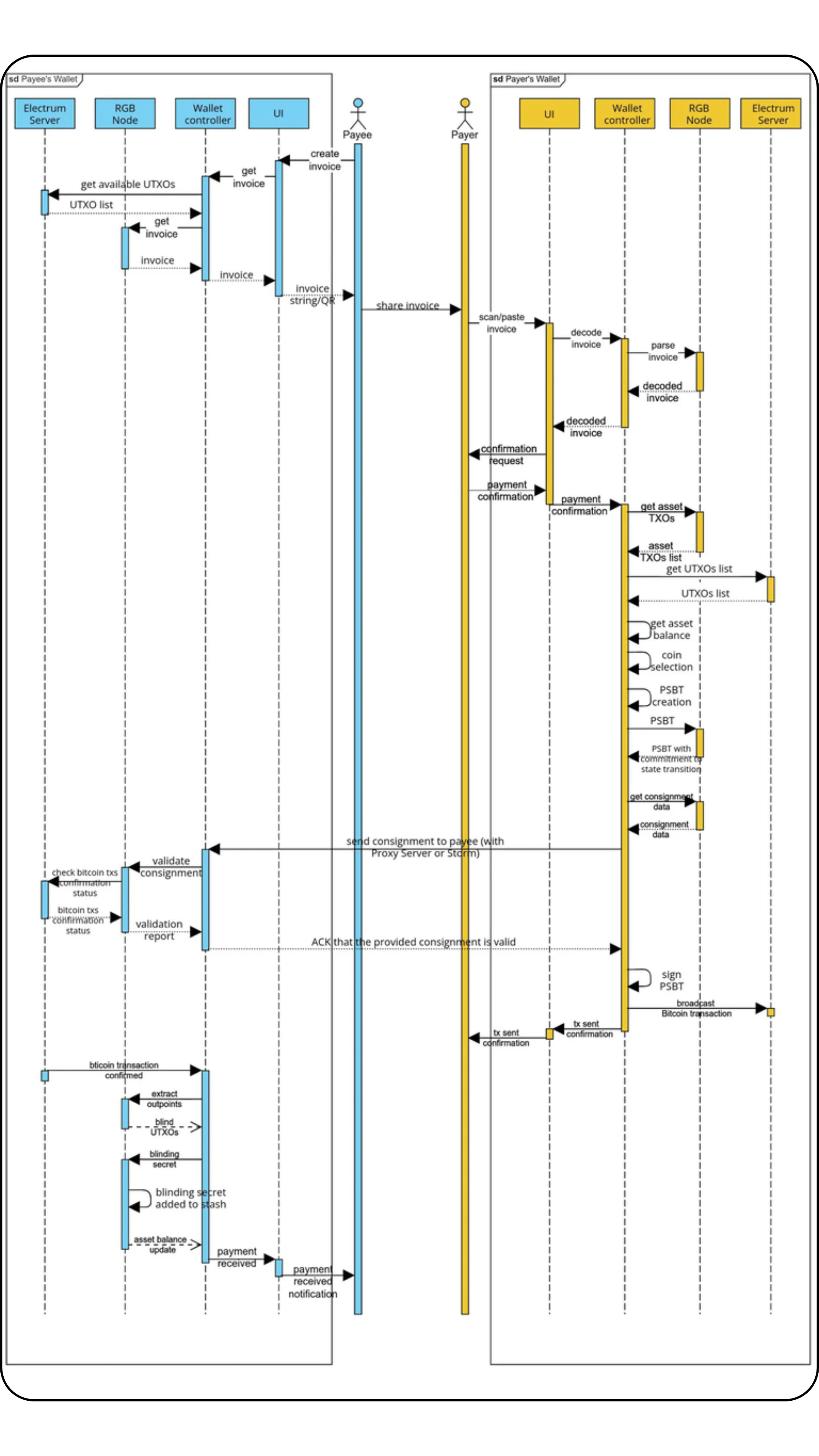

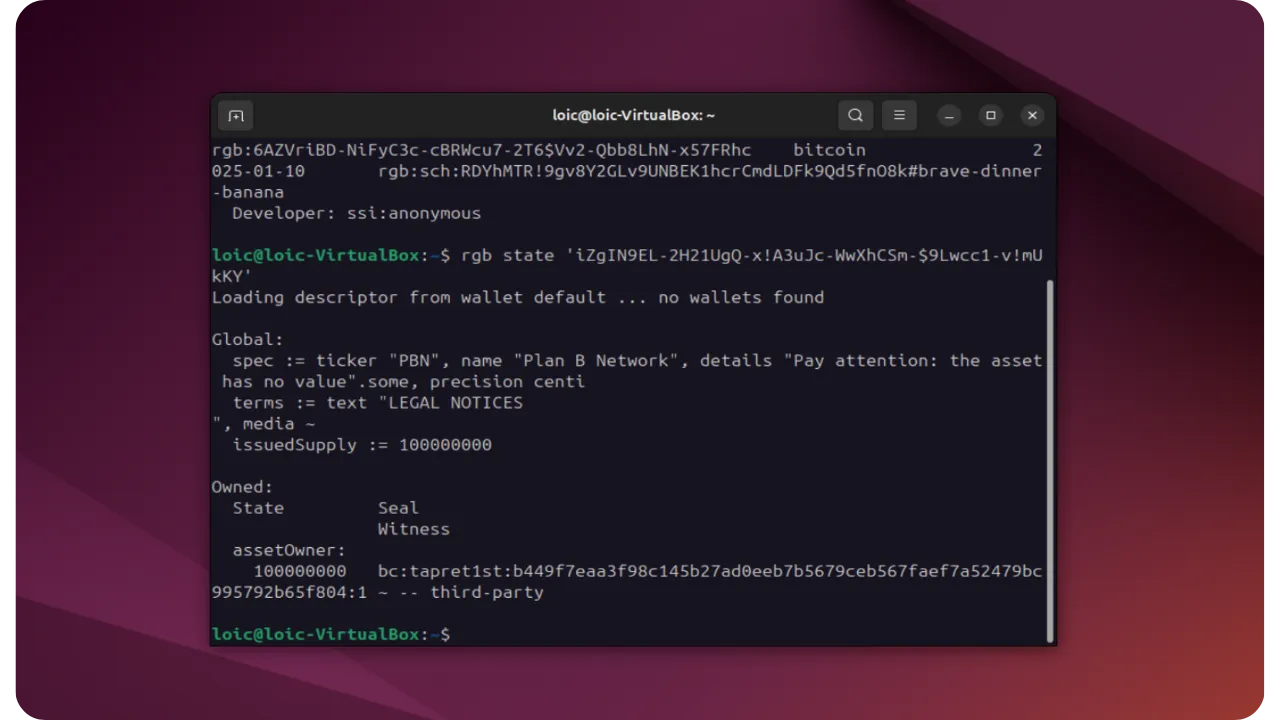

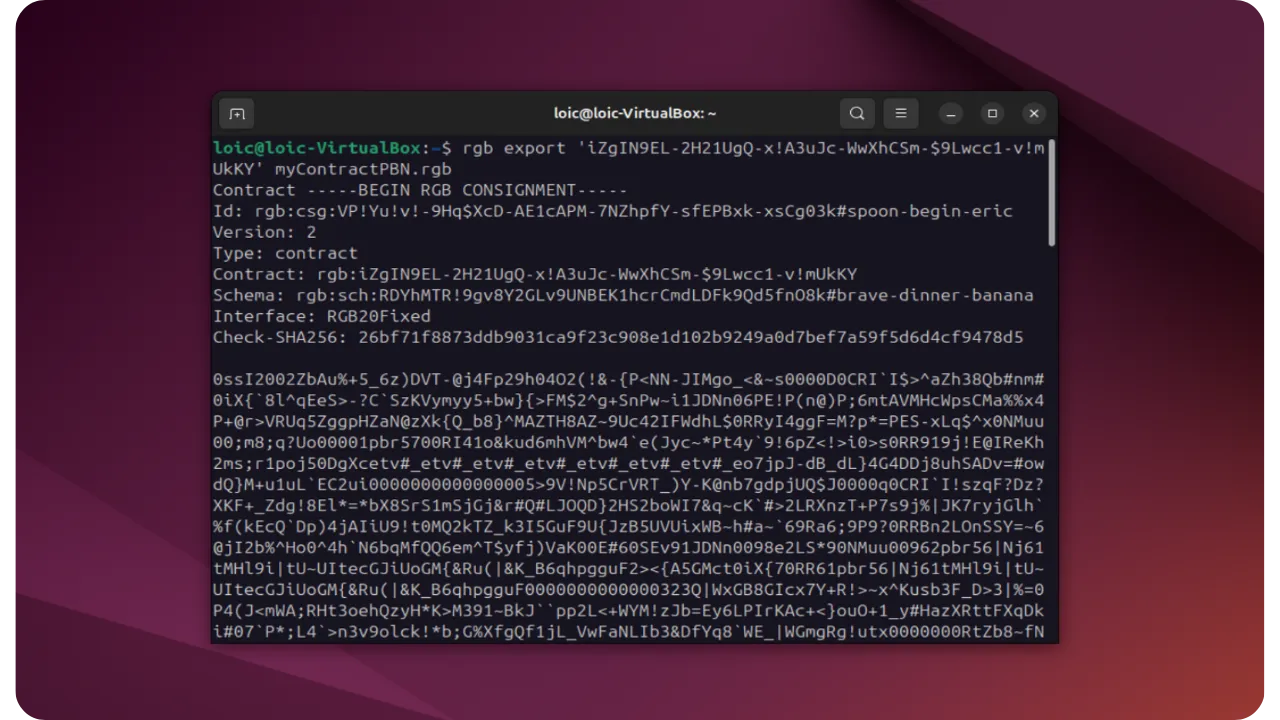

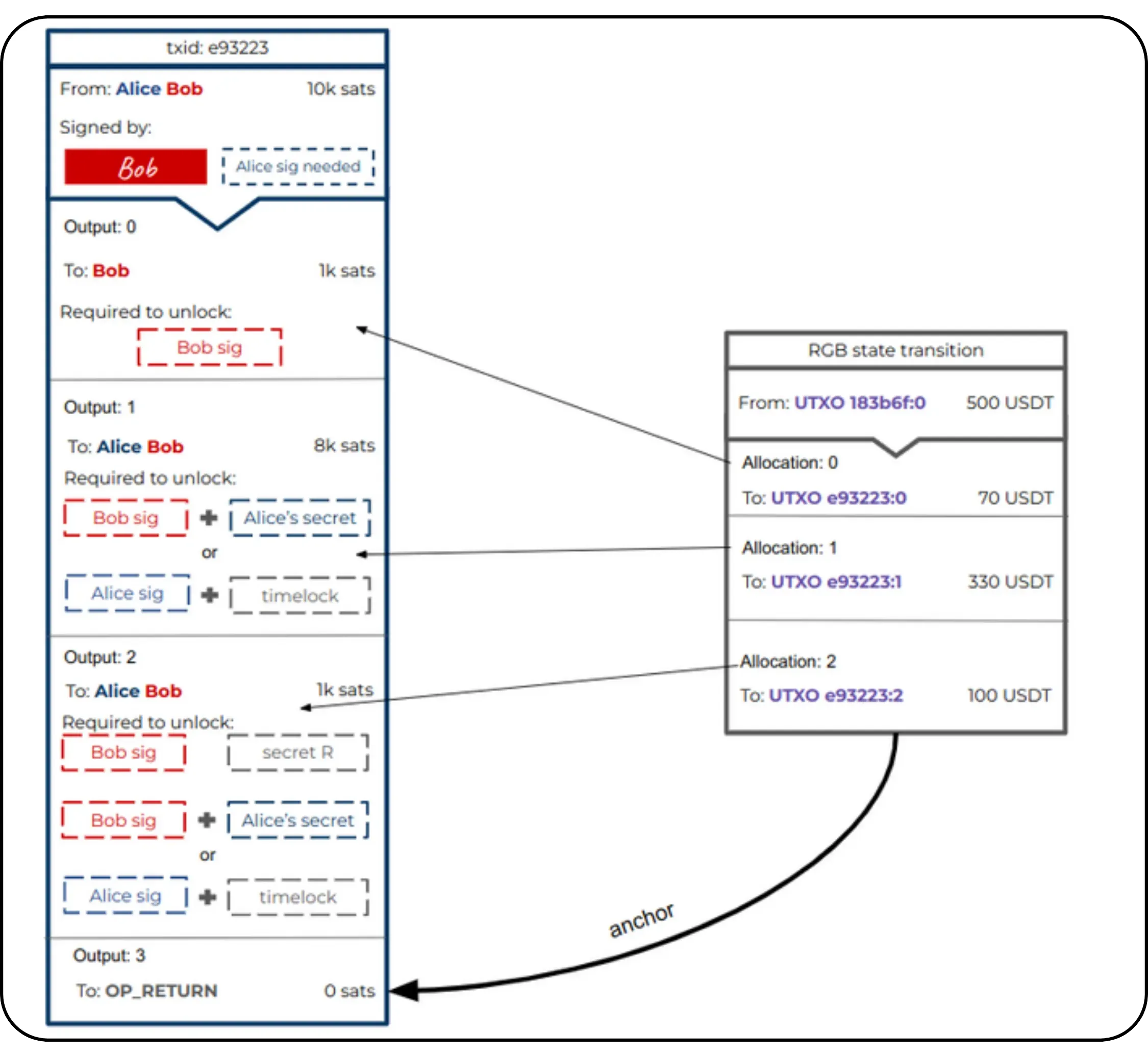

State transitions and their mechanics

The general principle is still that of Client-side Validation, where state data is held by the owner and validated by the recipient. However, the specificity here with RGB lies in the fact that Bob, as recipient, asks Alice to incorporate certain information into the contract data in order to have real control over the asset received, via a hidden reference to one of his UTXOs.

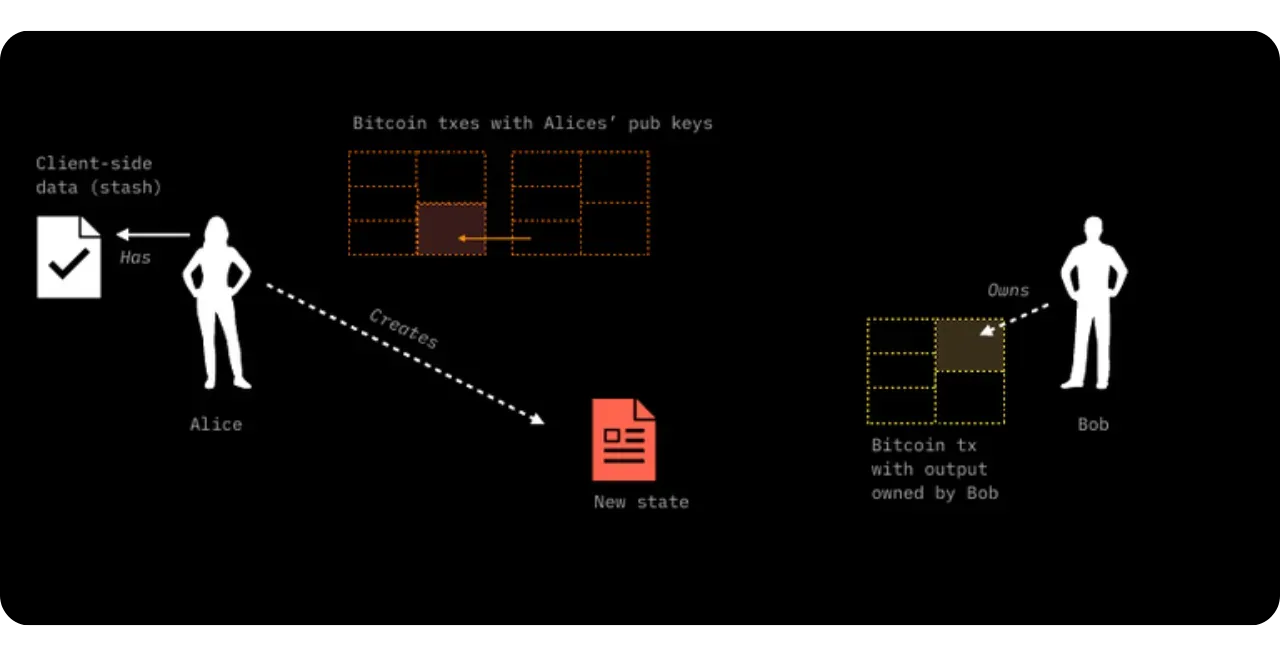

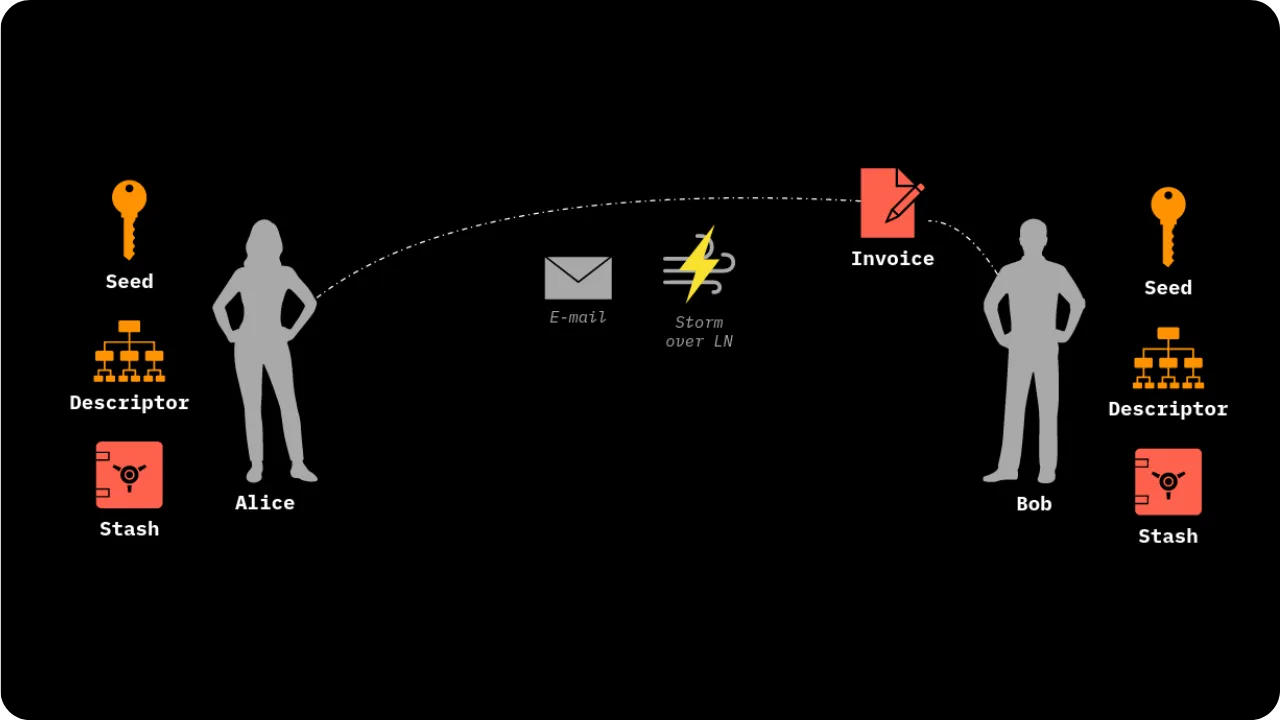

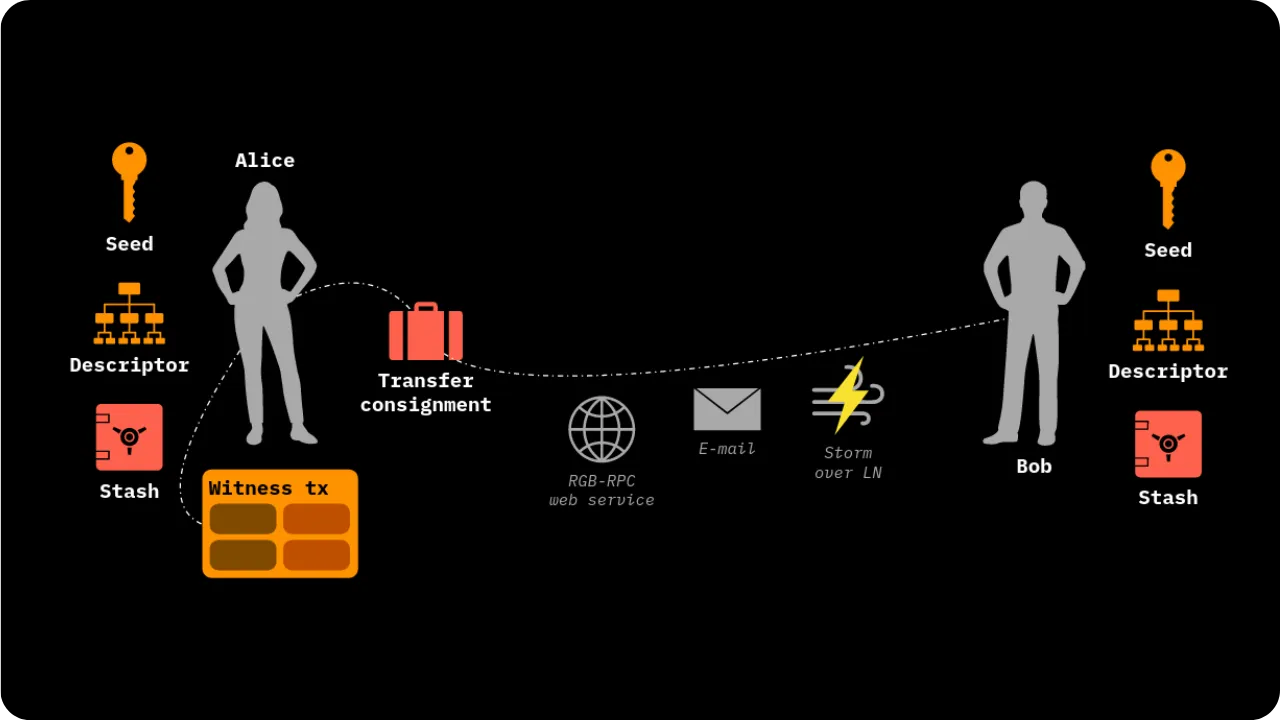

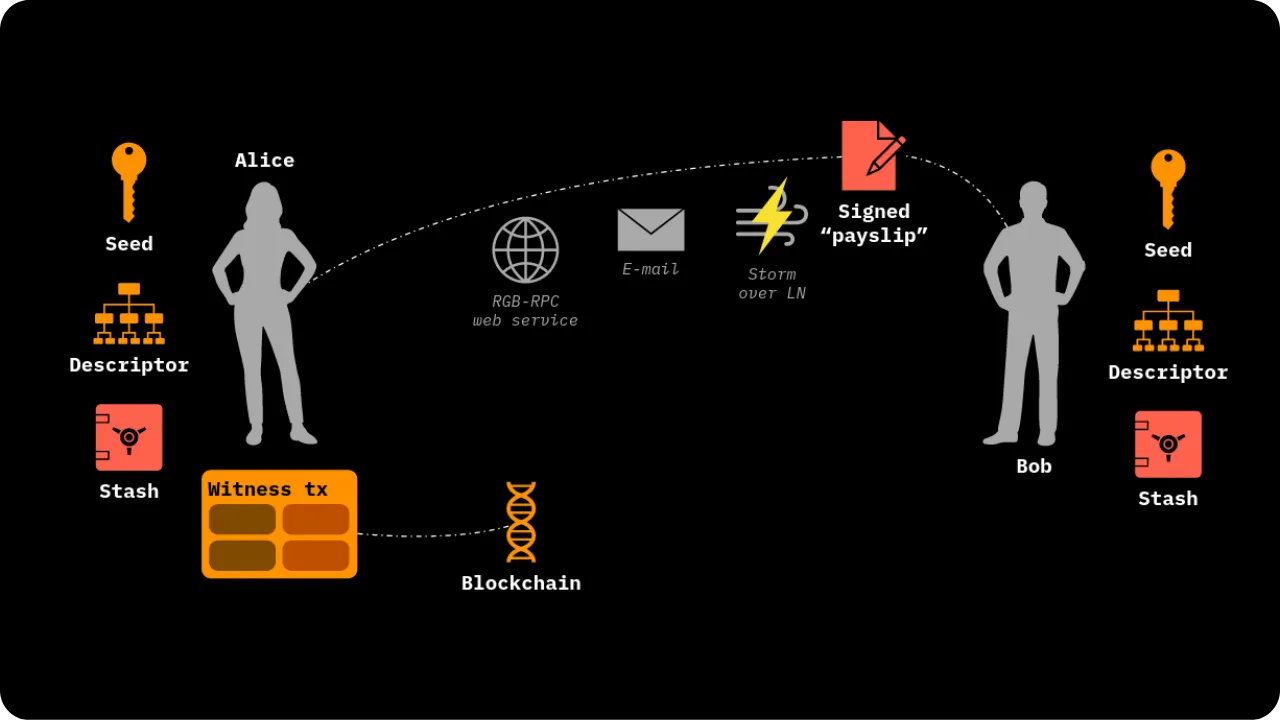

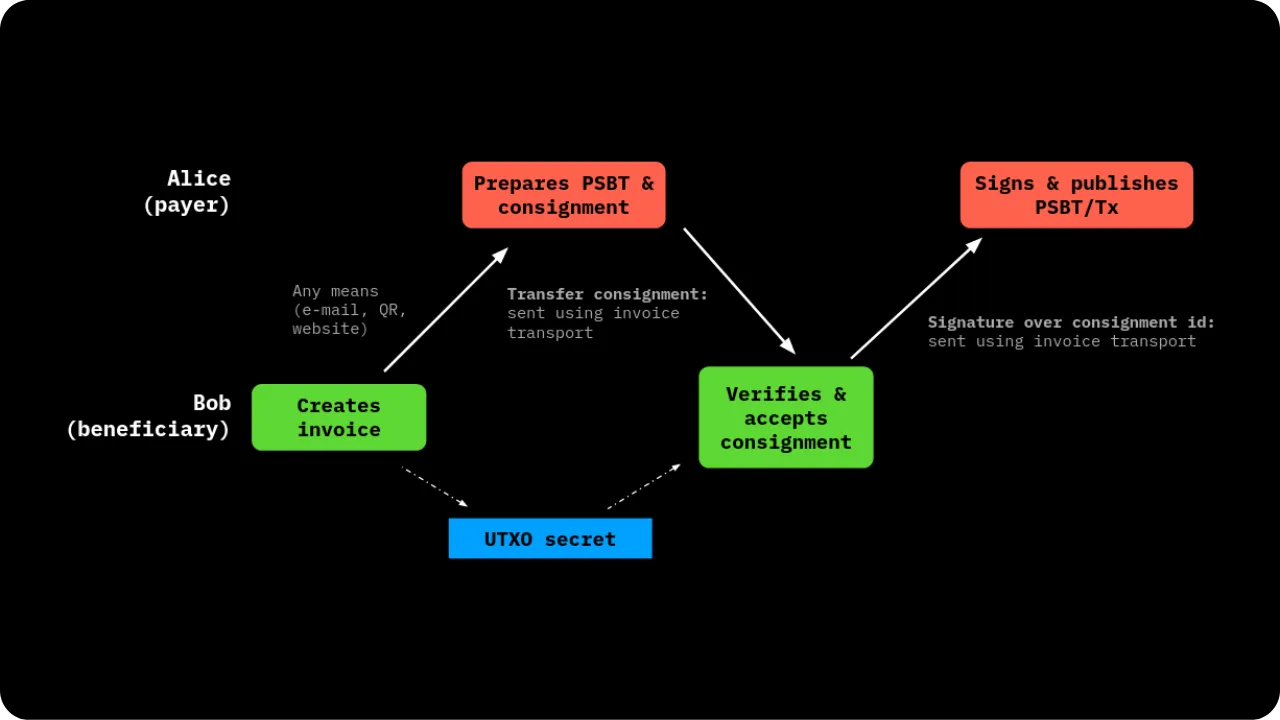

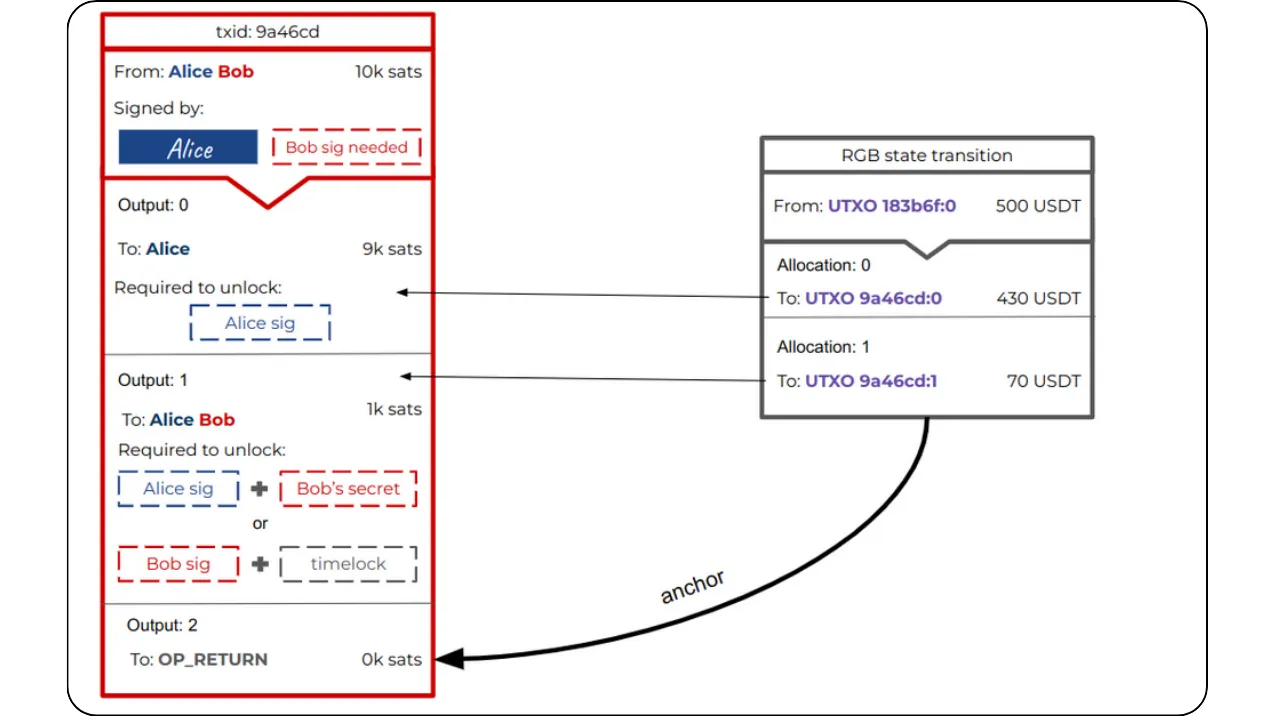

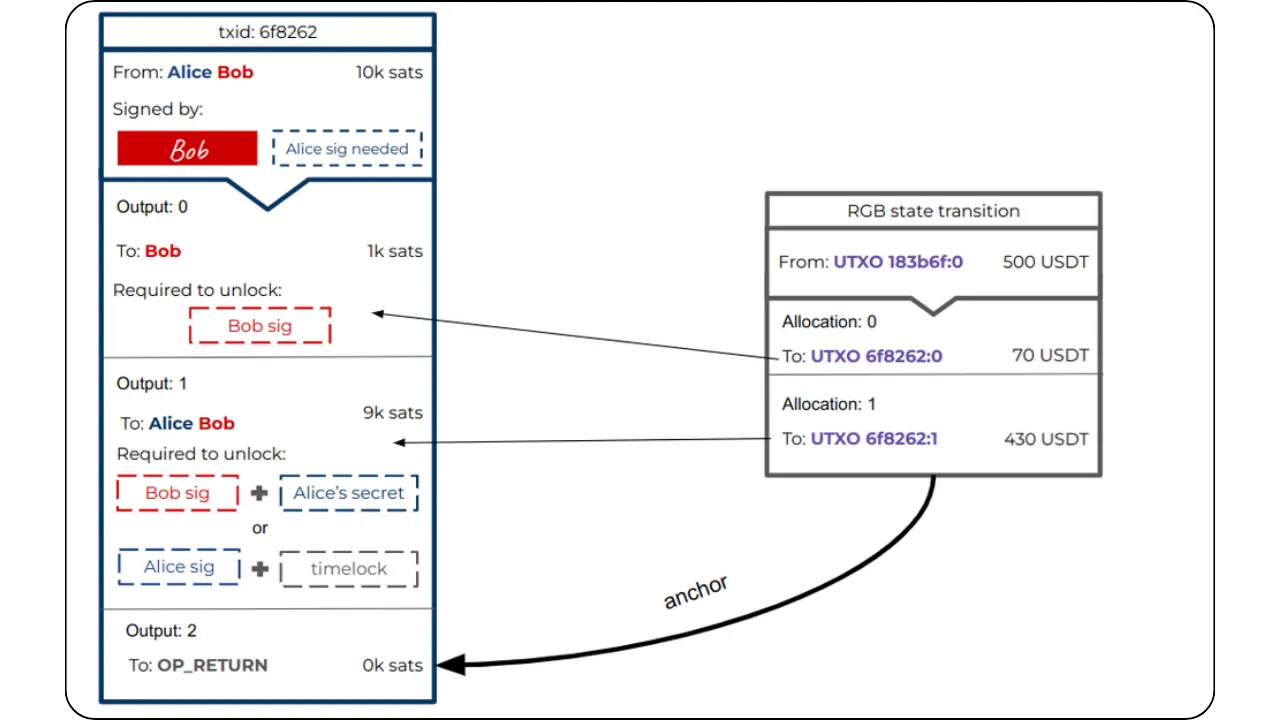

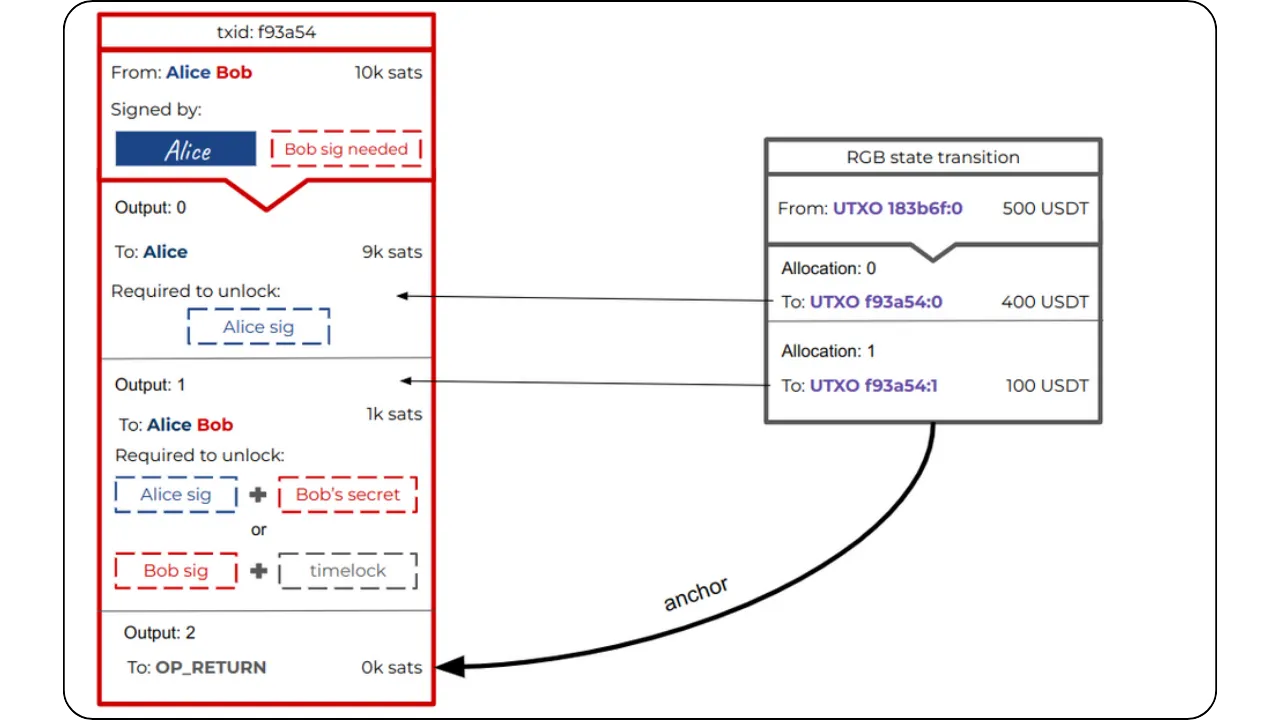

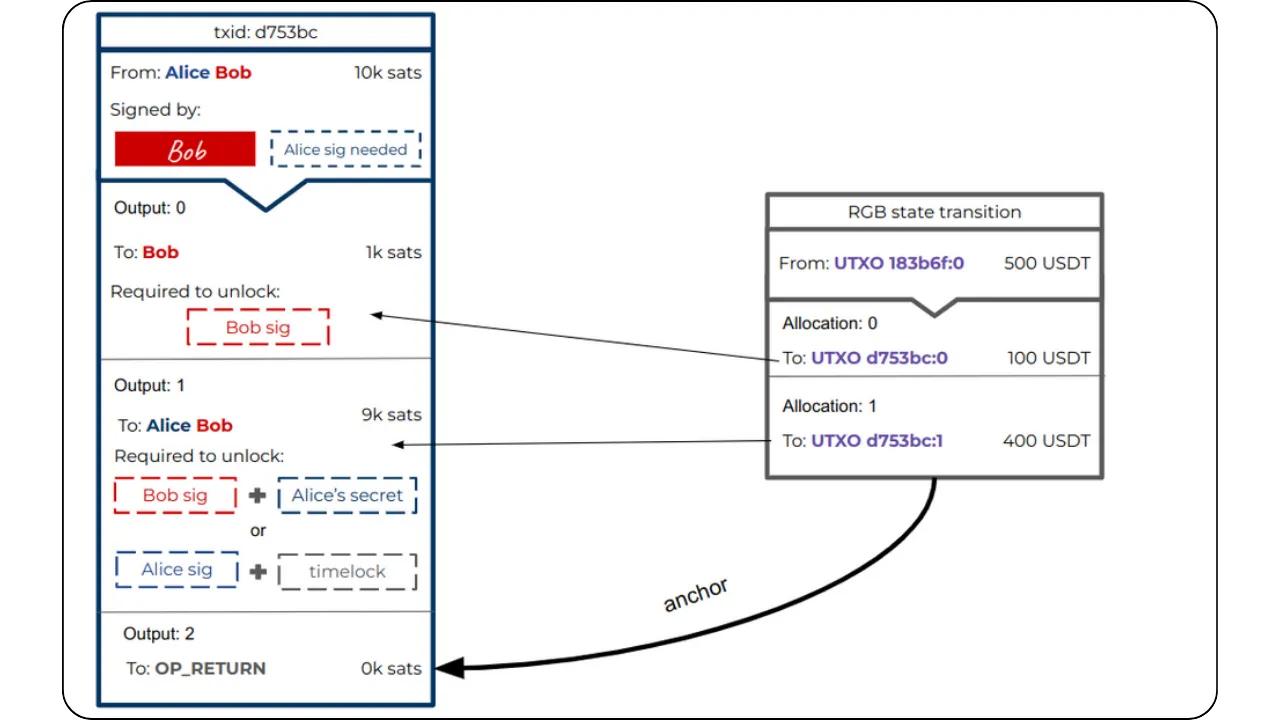

To illustrate the process of a State Transition (which is one of the fundamental Contract Operations in RGB), let's take a step-by-step example of an asset transfer between Alice and Bob:

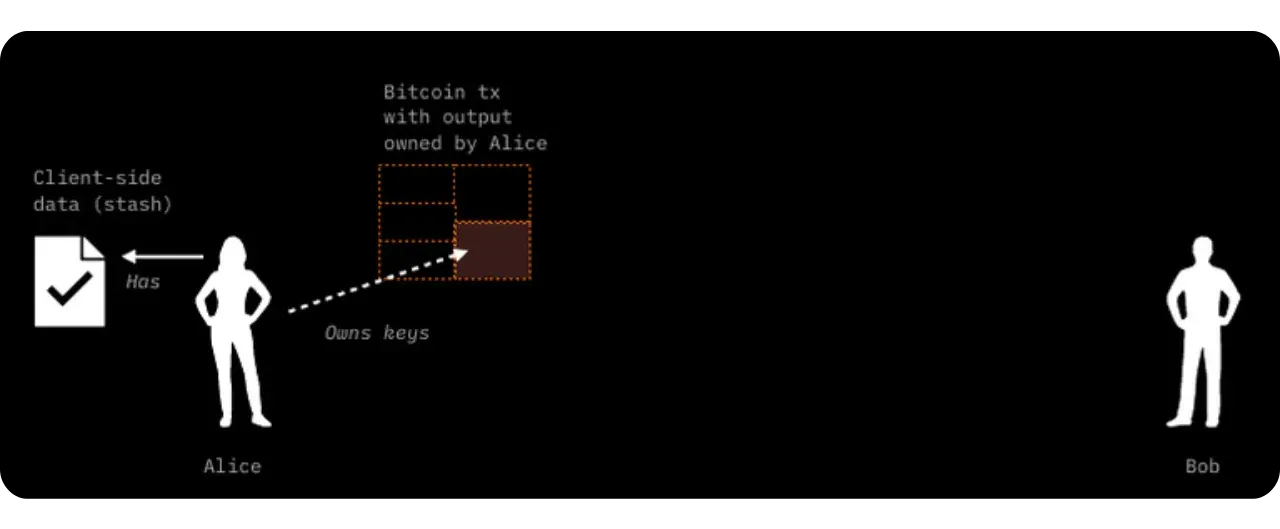

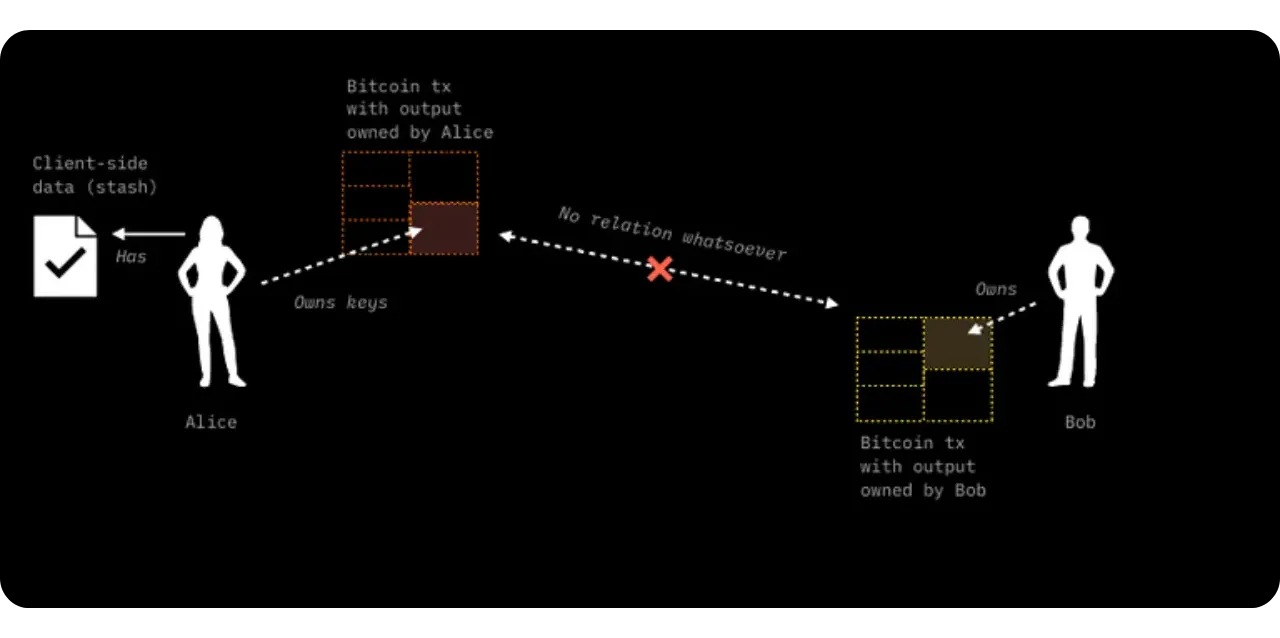

Initial situation:

Alice has a stash RGB of locally validated data (client-side). This stash refers to one of her UTXOs on Bitcoin. This means that a seal definition in this data points to a UTXO belonging to Alice. The idea is to enable her to transfer certain digital rights linked to an asset (e.g. RGB tokens) to Bob.

Bob also has UTXOs:

Bob, on the other hand, has at least one UTXO of his own, with no direct link to Alice's. In the event that Bob has no UTXO, it is still possible to make the transfer to him using the witness transaction itself: the output of this transaction will then include the commitment (commitment) and implicitly associate ownership of the new contract with Bob.

Construction of the new property (New State):