name: Privacy on Bitcoin goal: Understand and master the principles of privacy protection when using Bitcoin objectives:

- Define the theoretical concepts needed to understand privacy issues

- Identify and mitigate the risks associated with loss of confidentiality for Bitcoin users

- Using methods and tools to protect your privacy on Bitcoin

- Understand chain analysis methods and develop defense strategies

Protect your privacy on Bitcoin

In a world where the confidentiality of financial transactions is gradually becoming a luxury, understanding and mastering the principles of privacy protection when using Bitcoin is essential. This training course gives you all the keys, both theoretical and practical, to achieve this autonomously.

Today, on Bitcoin, companies specialize in blockchain analysis. Their core business consists precisely in intruding into your private sphere, in order to compromise the confidentiality of your transactions. In reality, there is no such thing as a "right to privacy" in Bitcoin. So it's up to you, the user, to assert your natural rights and protect the confidentiality of your transactions, because nobody else is going to do it for you.

The course is designed to be comprehensive and general. Each technical concept is covered in detail and supported by explanatory diagrams. The aim is to make the knowledge accessible to all. BTC204 is therefore affordable for beginners and intermediate users. The course also offers added value for more experienced bitcoiners, as we delve deeper into certain technical concepts that are often misunderstood.

Join us to transform your use of Bitcoin and become an informed user, capable of understanding the issues around confidentiality and protecting your privacy.

Introduction

Course overview

Welcome to the BTC204 course!

In a world where the confidentiality of financial transactions is gradually becoming a luxury, understanding and mastering the principles of privacy protection when using Bitcoin is essential. This training course gives you all the keys, both theoretical and practical, to achieve this autonomously.

Today, on Bitcoin, companies specialize in blockchain analysis. Their core business consists precisely in intruding into your private sphere, in order to compromise the confidentiality of your transactions. In reality, there is no such thing as a "right to privacy" in Bitcoin. So it's up to you, the user, to assert your natural rights and protect the confidentiality of your transactions, because nobody else is going to do it for you.

Bitcoin isn't just about "Number Go Up" and preserving the value of savings. With its unique characteristics and history, it is first and foremost the tool of the counter-economy. Thanks to this formidable invention, you can freely dispose of your money, spend it and accumulate it, without anyone being able to stop you.

Bitcoin offers a peaceful escape from the yoke of the state, allowing you to fully enjoy your natural rights, which cannot be challenged by established laws. Thanks to Satoshi Nakamoto's invention, you have the power to enforce respect for your private property and regain the freedom to contract.

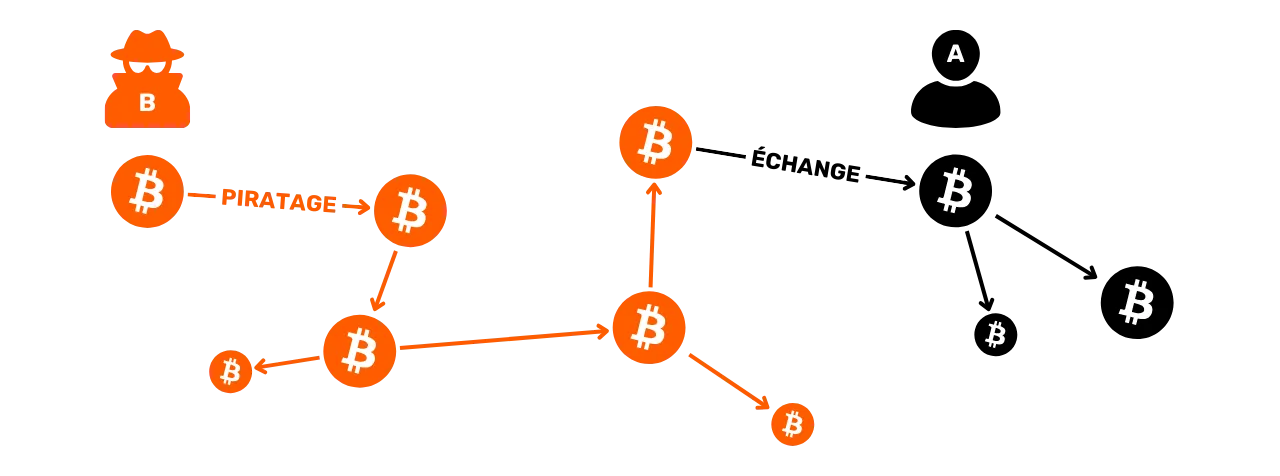

However, Bitcoin is not anonymous by default, which can represent a risk for individuals engaged in the counter-economy, particularly in regions under despotic rule. But this is not the only danger. Since bitcoin is a valuable and incensurable asset, it can be a target for thieves. So protecting your privacy becomes a matter of security too: it can help you prevent hacking and physical assault.

As we'll see, although the protocol offers certain confidentiality protections in its own right, it's crucial to use additional tools to optimize and defend this confidentiality.

This training course is designed to provide a comprehensive, general overview of the issues involved in Bitcoin confidentiality. Each technical concept is covered in detail, supported by explanatory diagrams. The aim is to make this knowledge accessible to everyone, even beginners and intermediate users. For the more seasoned Bitcoiners, we also cover highly technical and sometimes little-known concepts throughout the course, to deepen understanding of each subject.

The aim of this training course is not to make you totally anonymous in your use of Bitcoin, but rather to provide you with the essential tools to know how to protect your confidentiality according to your personal objectives. You'll have the freedom to choose from the concepts and tools presented to develop your own strategies, tailored to your specific goals and needs.

Section 1: Definitions and key concepts

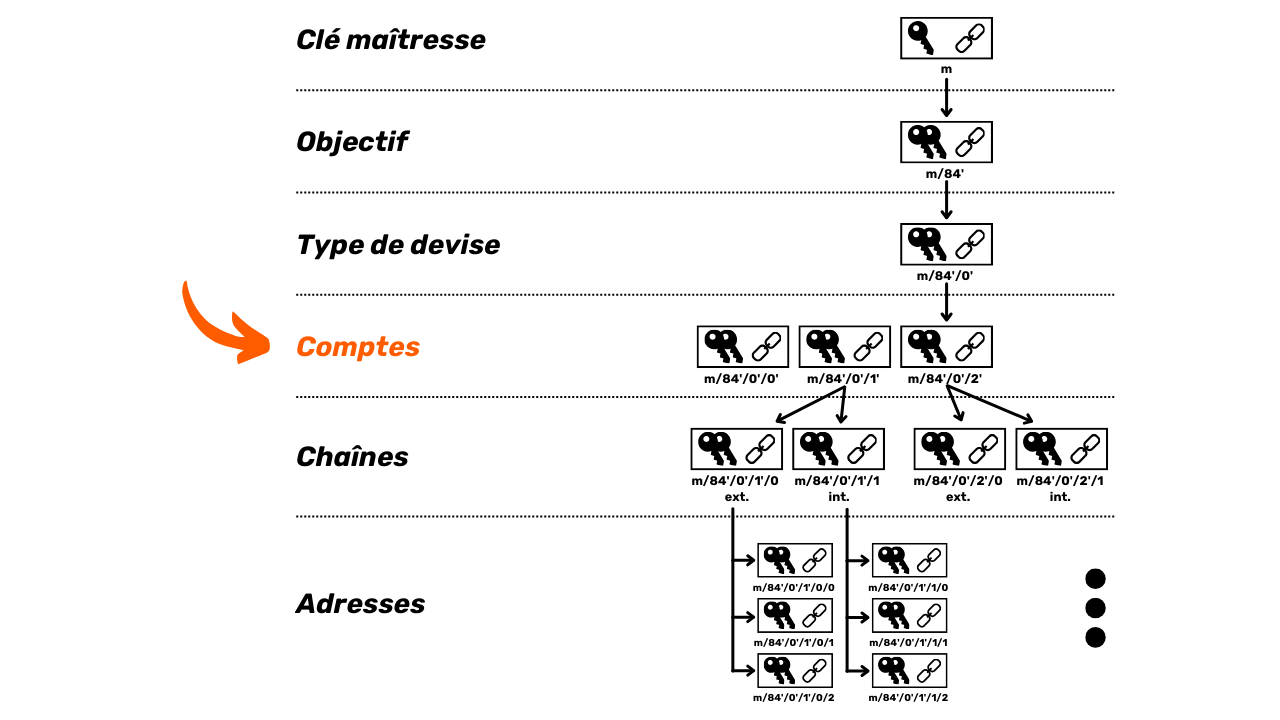

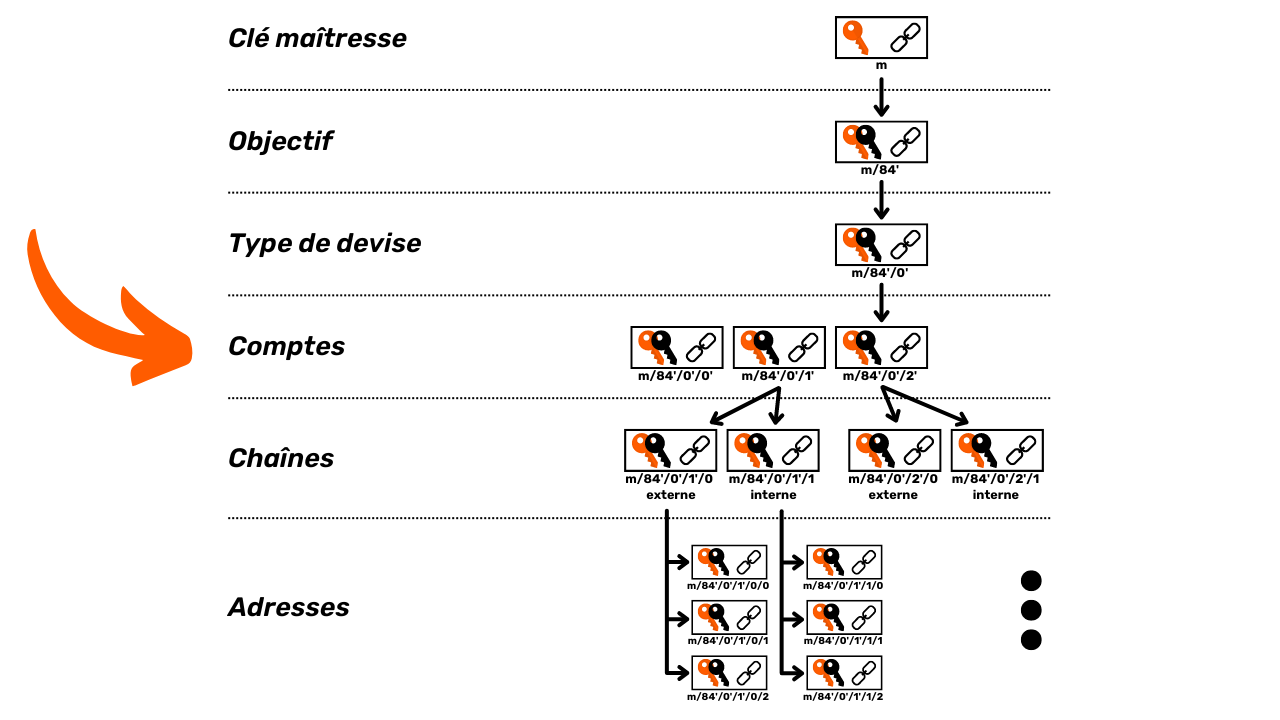

To begin with, we're going to review the fundamental principles governing the operation of Bitcoin, so that we can then calmly tackle the notions relating to confidentiality. It's essential to master a few basic concepts, such as UTXO, receiving addresses and scripting, before you can fully understand the concepts we'll cover in the following sections. We will also introduce Bitcoin's general confidentiality model, as imagined by Satoshi Nakamoto, which will enable us to grasp the associated stakes and risks.

Section 2: Understanding and protecting against chain analysis

In the second section, we look at the techniques used by blockchain analysis companies to track your activity on Bitcoin. Understanding these methods is crucial to strengthening your privacy protection. The aim of this section is to examine attackers' strategies in order to better understand the risks and prepare the ground for the techniques we will study in the following sections. We will analyze transaction patterns, internal and external heuristics, and likely interpretations of these patterns. In addition to theory, we'll learn how to use a block explorer for chain analysis, through practical examples and exercises.

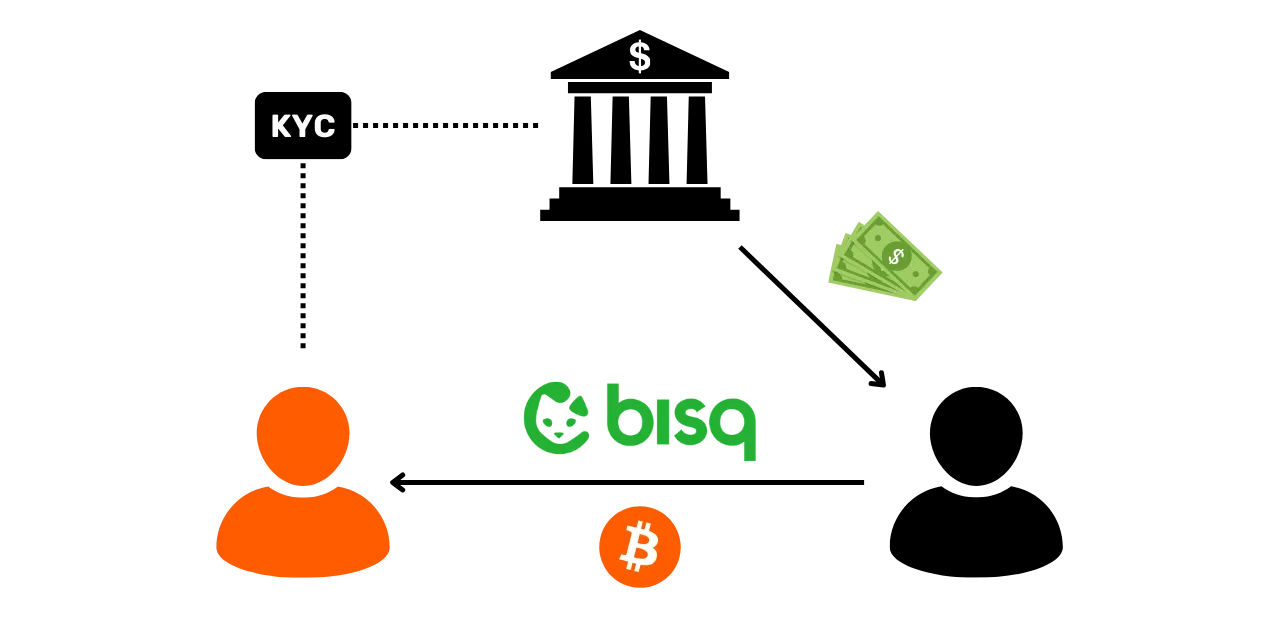

Section 3: Mastering best practices to protect your privacy

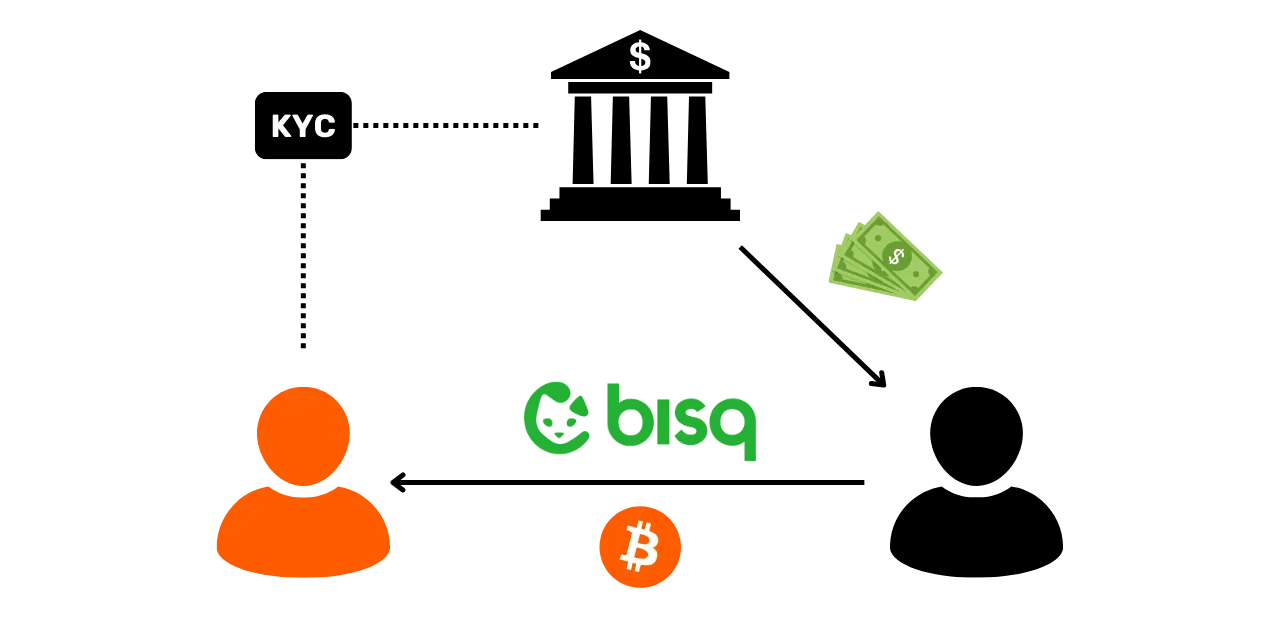

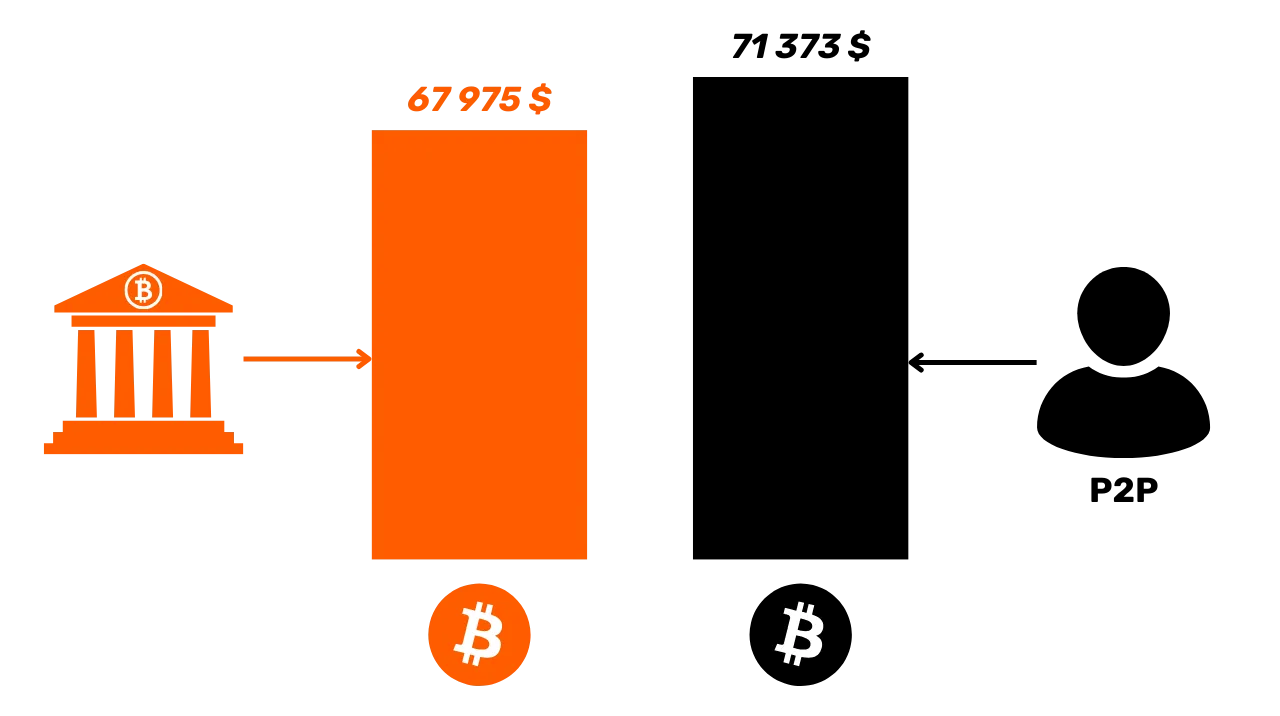

In the third section of our training course, we get down to the nitty-gritty: practice! The aim is to master all the essential best practices that should become natural reflexes for any Bitcoin user. We'll be covering the use of blank addresses, tagging, consolidation, the use of complete nodes, as well as KYC and acquisition methods. The aim is to provide you with a comprehensive overview of the pitfalls to avoid in order to establish a solid foundation in our quest to protect privacy. For some of these practices, you will be guided to a specific tutorial on how to implement them.

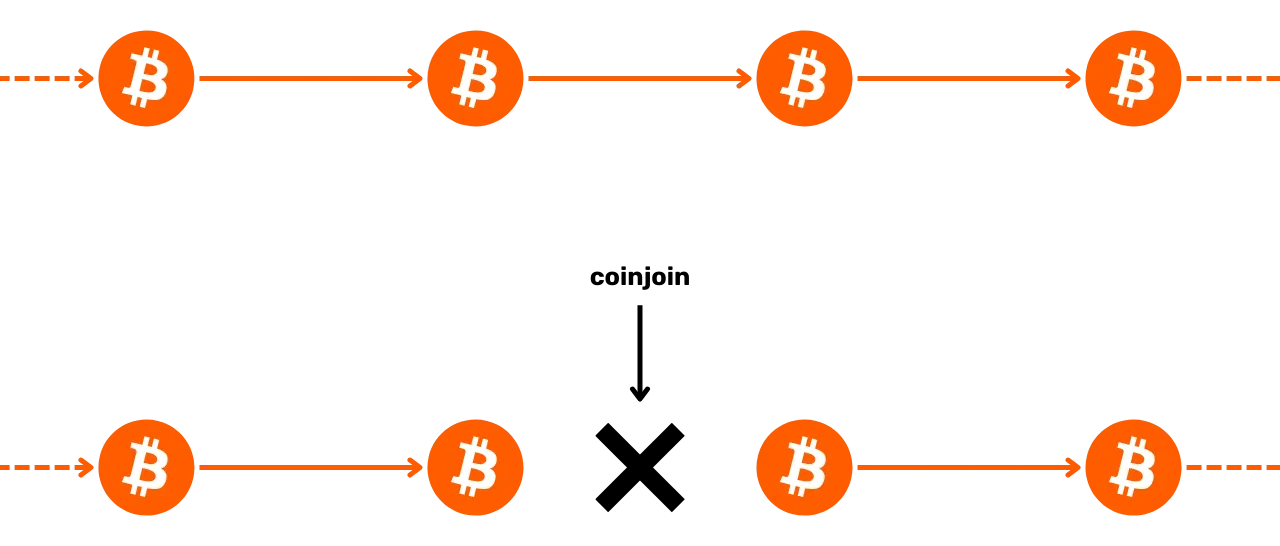

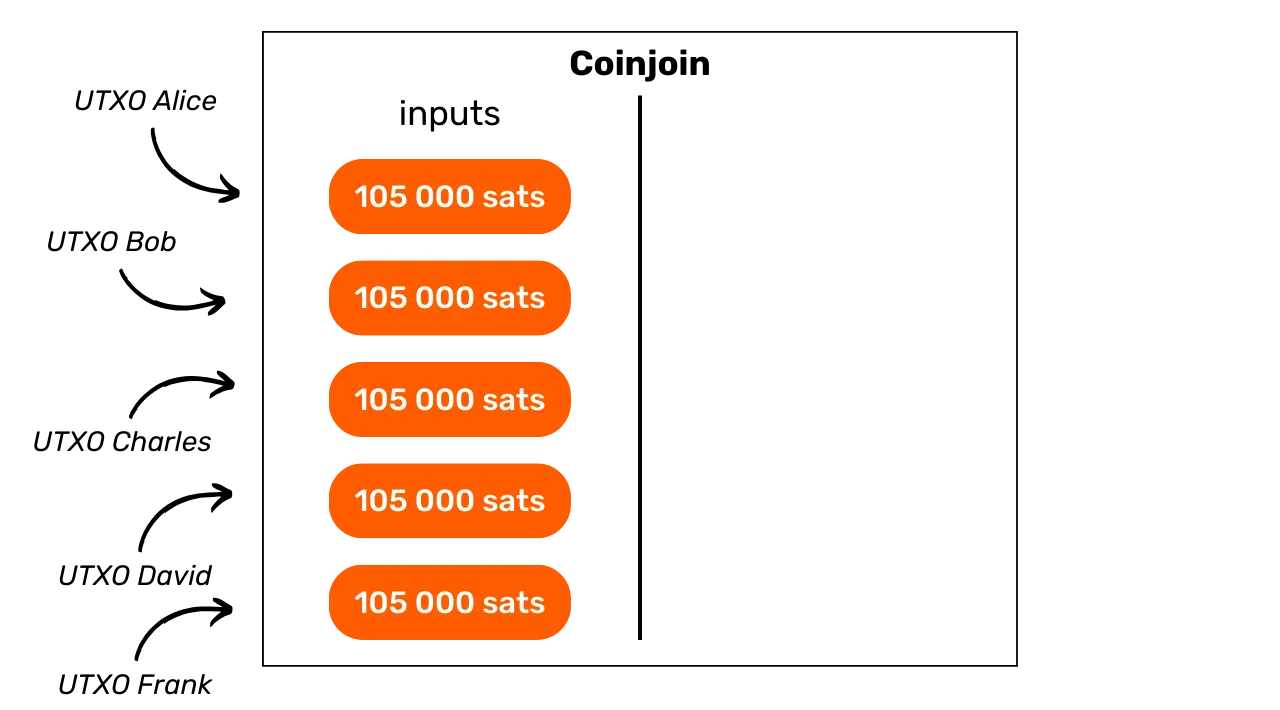

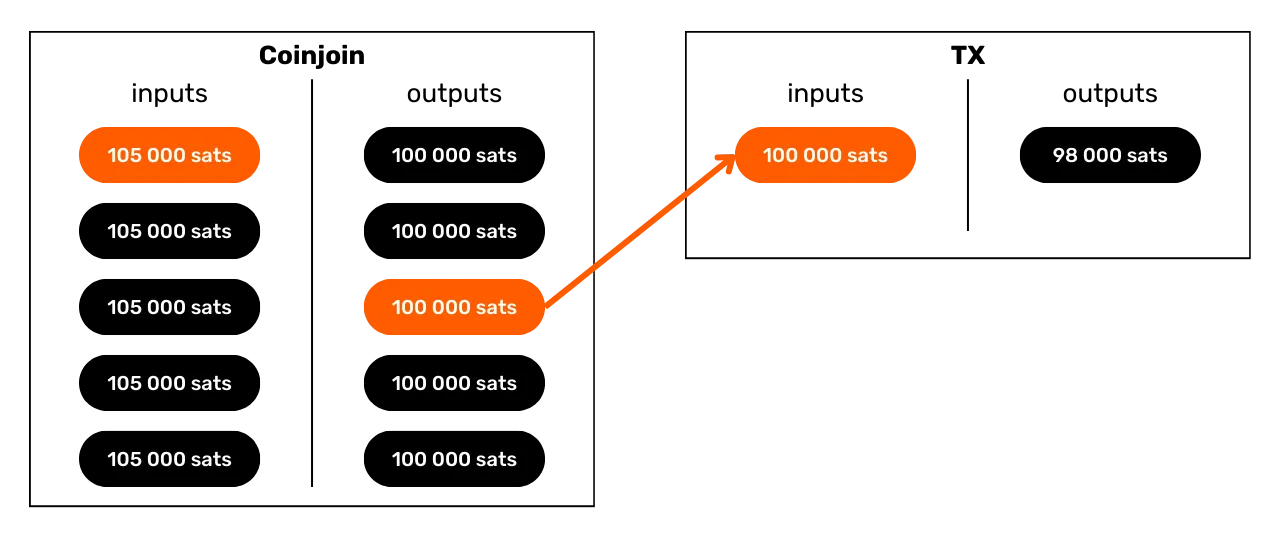

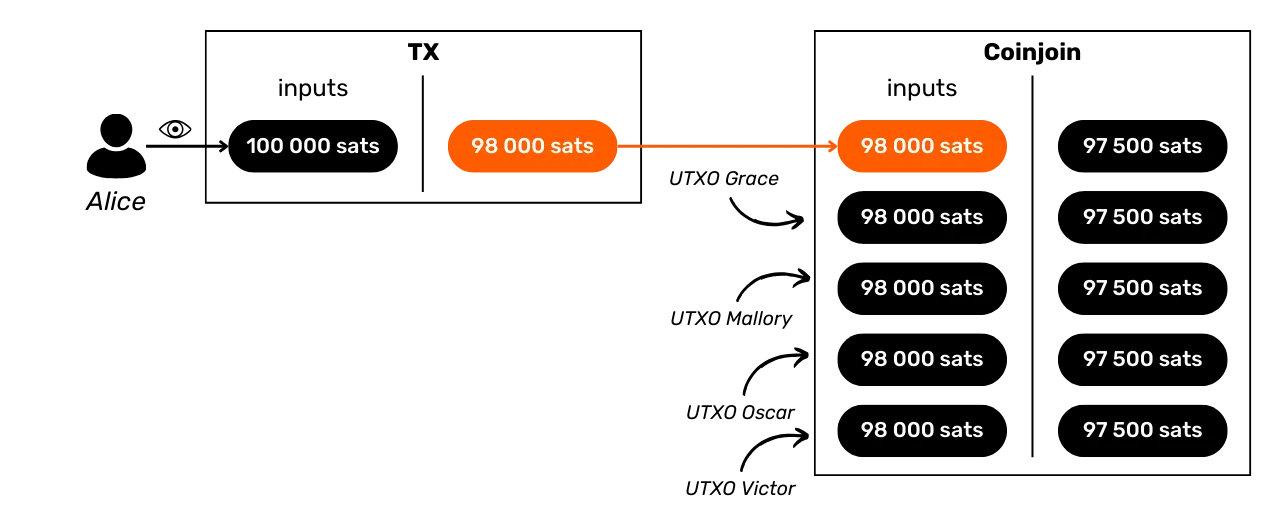

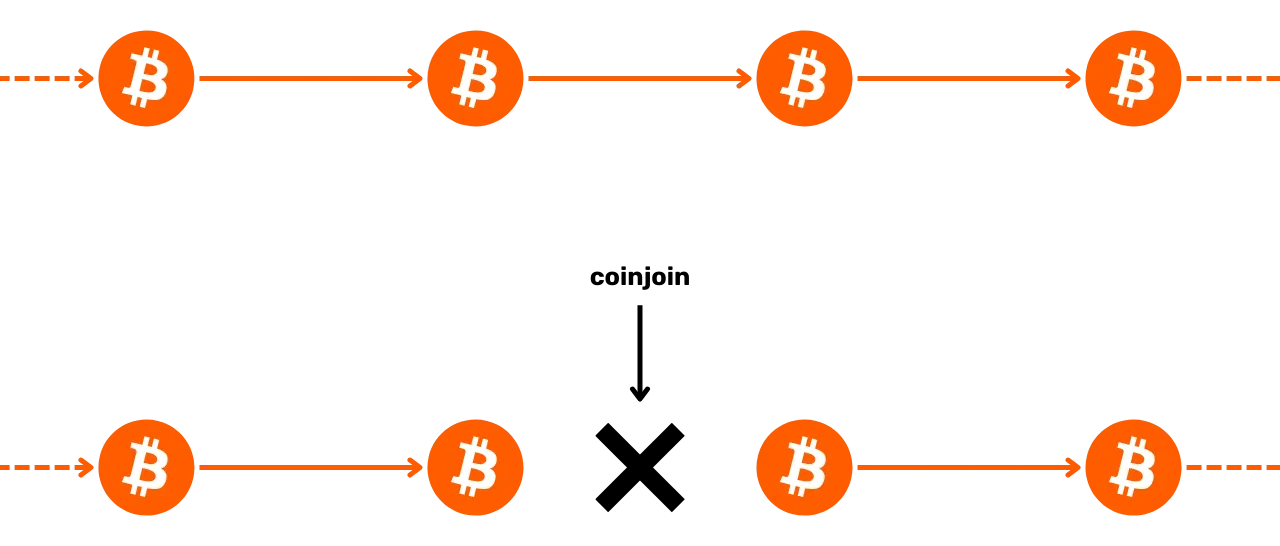

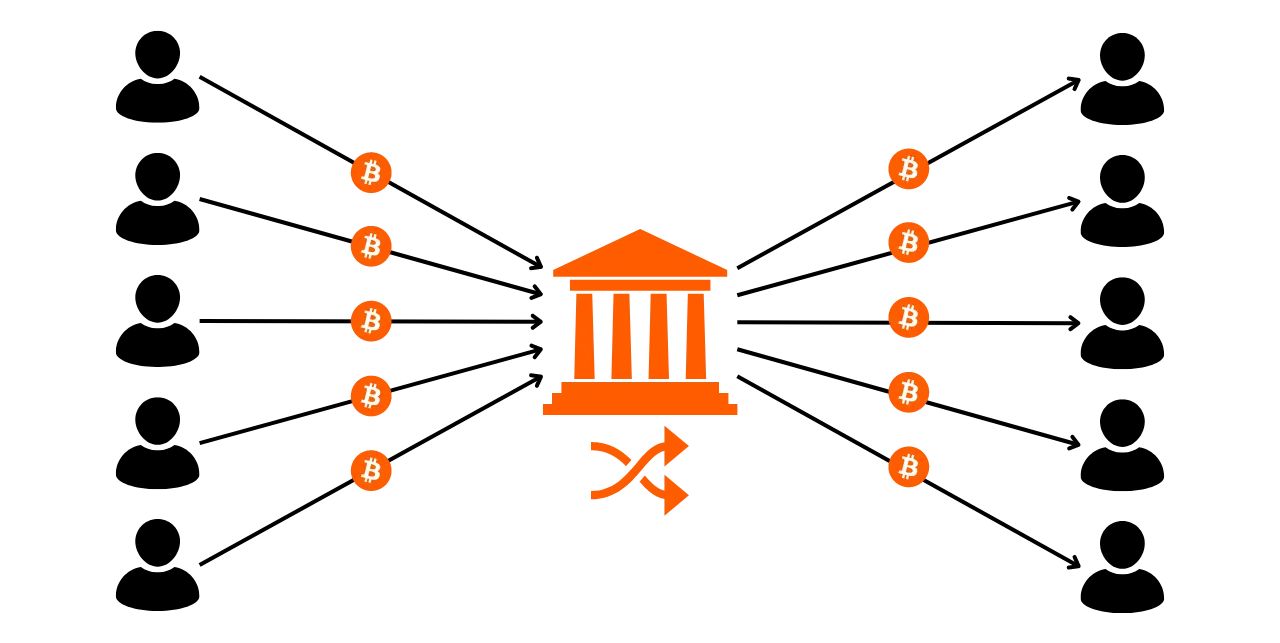

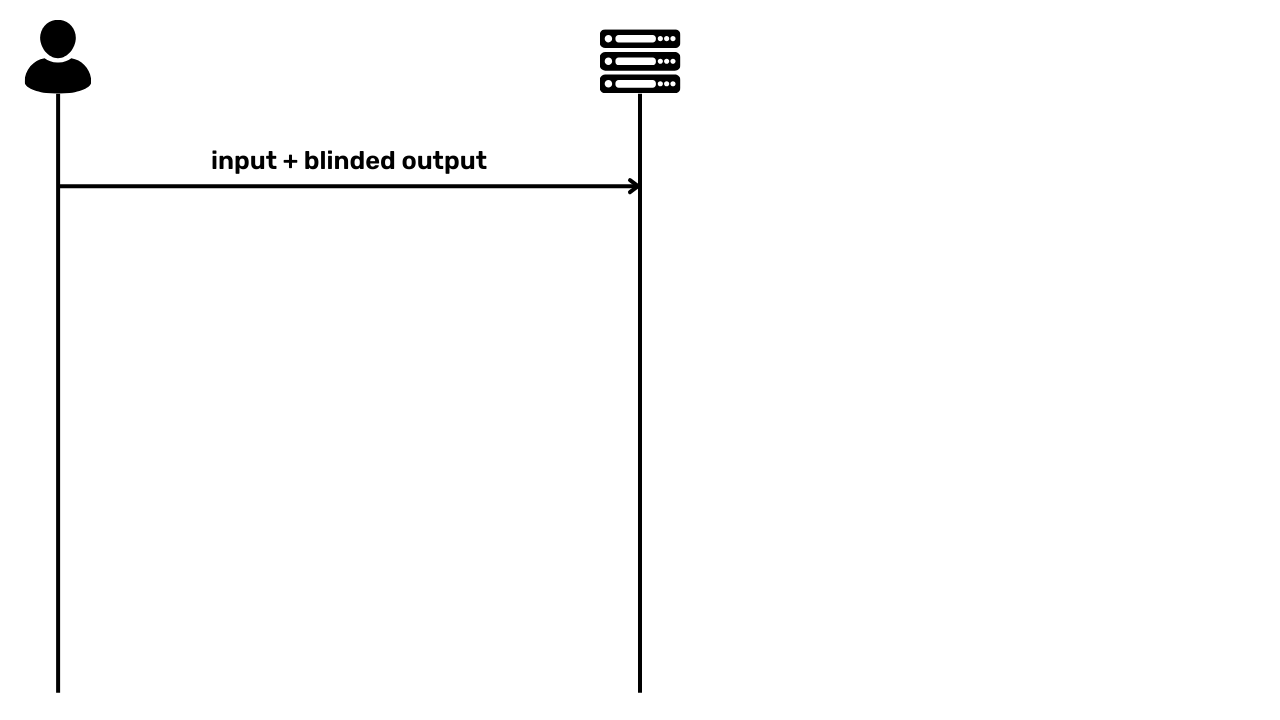

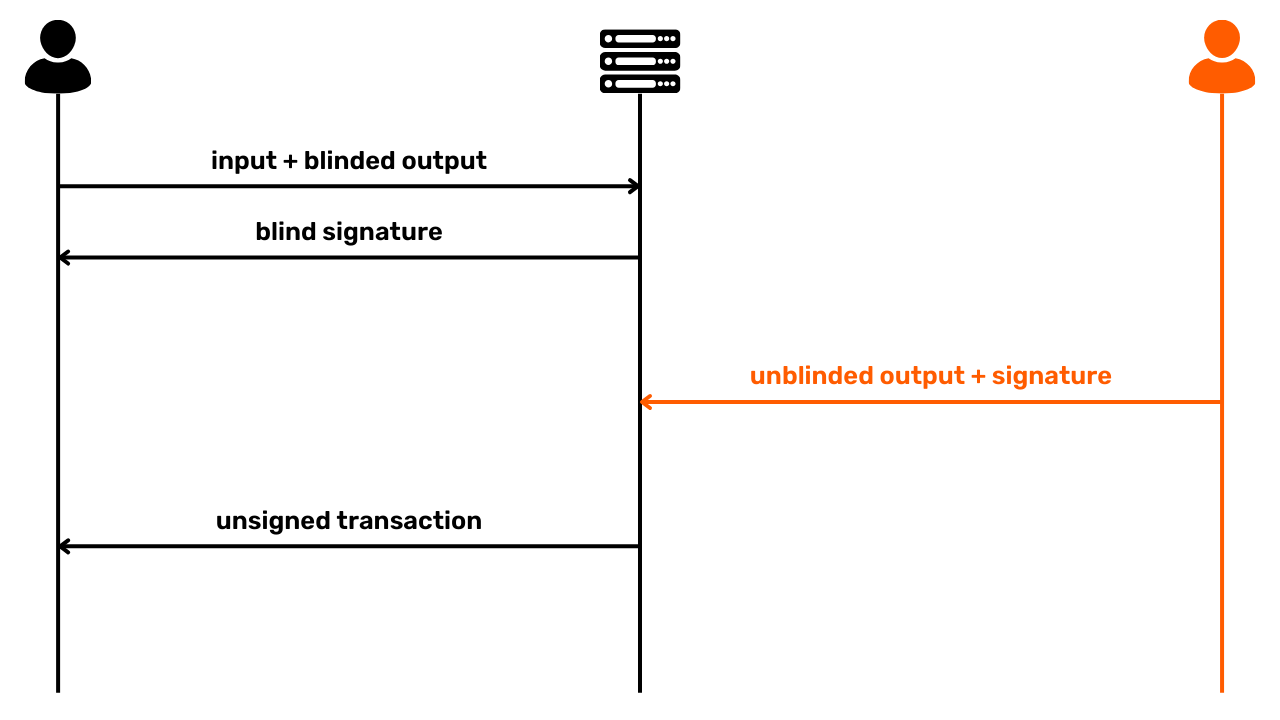

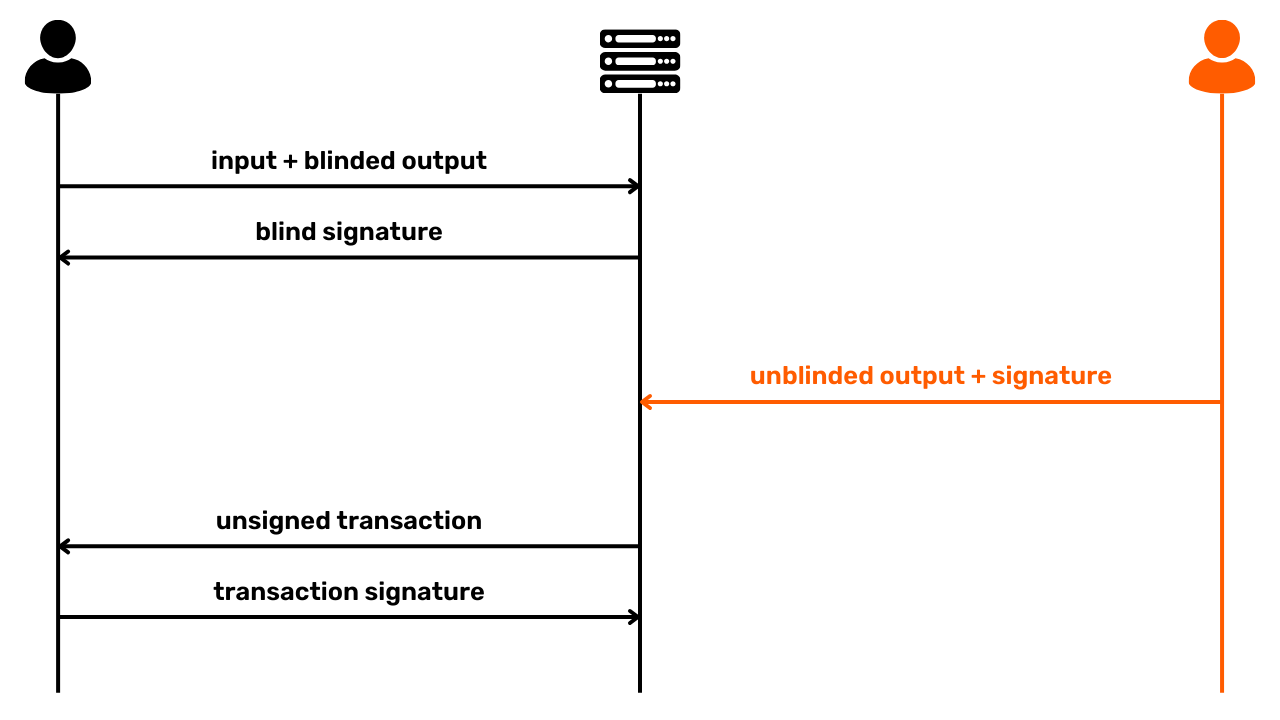

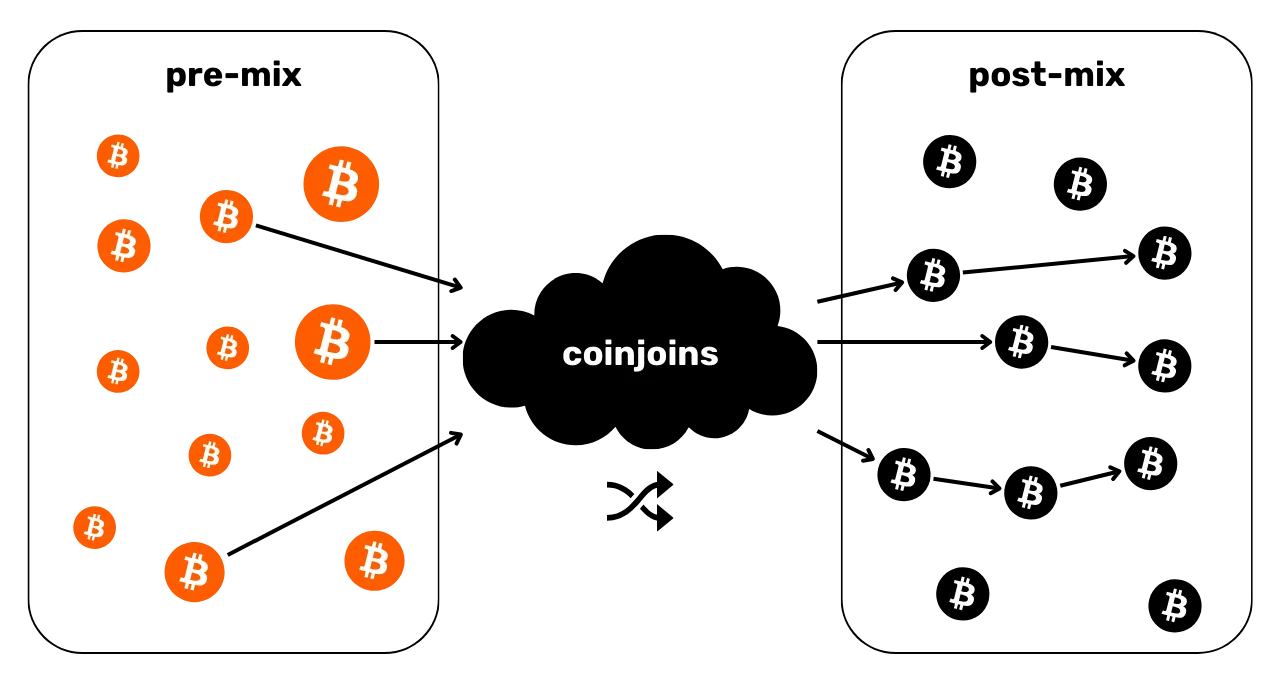

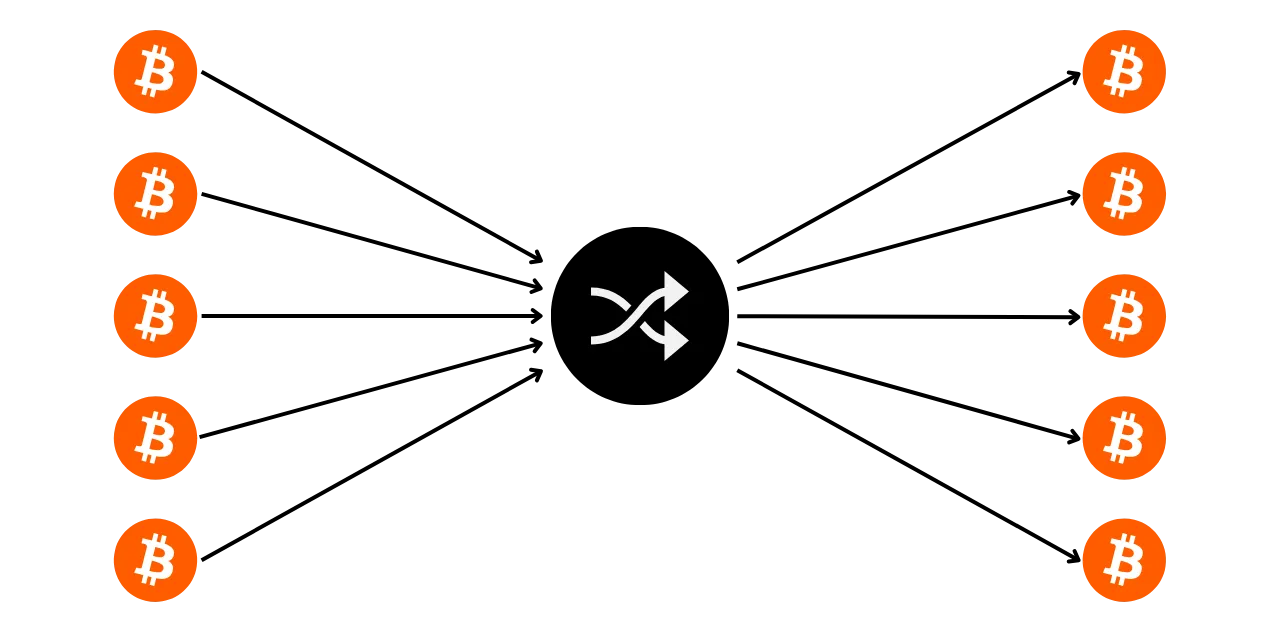

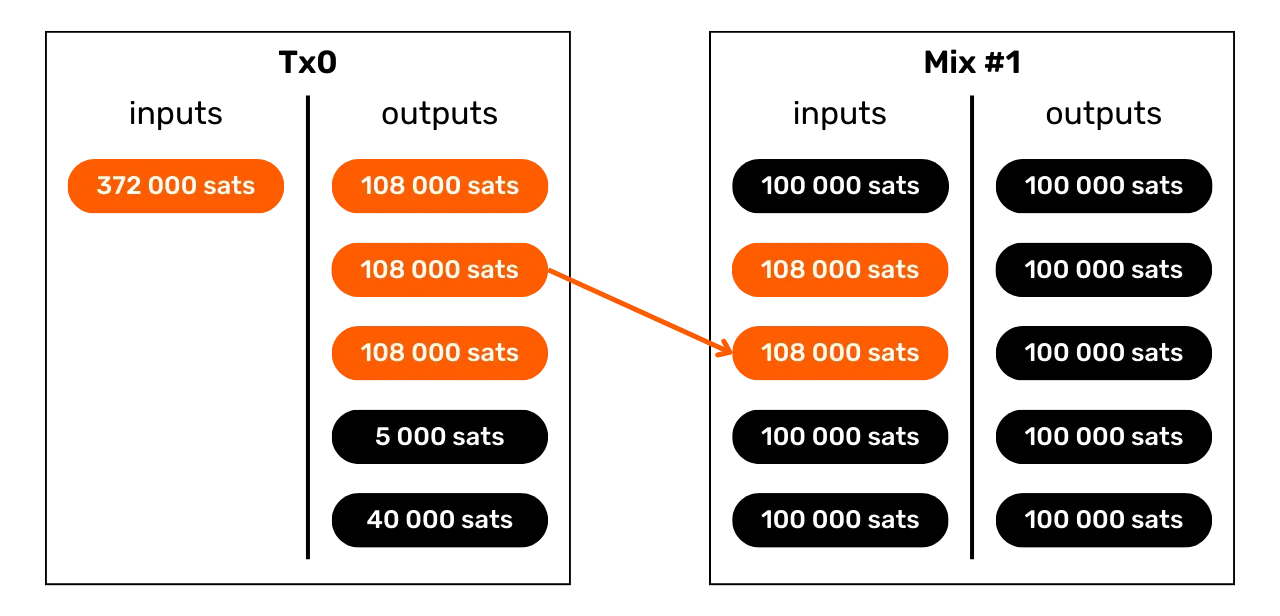

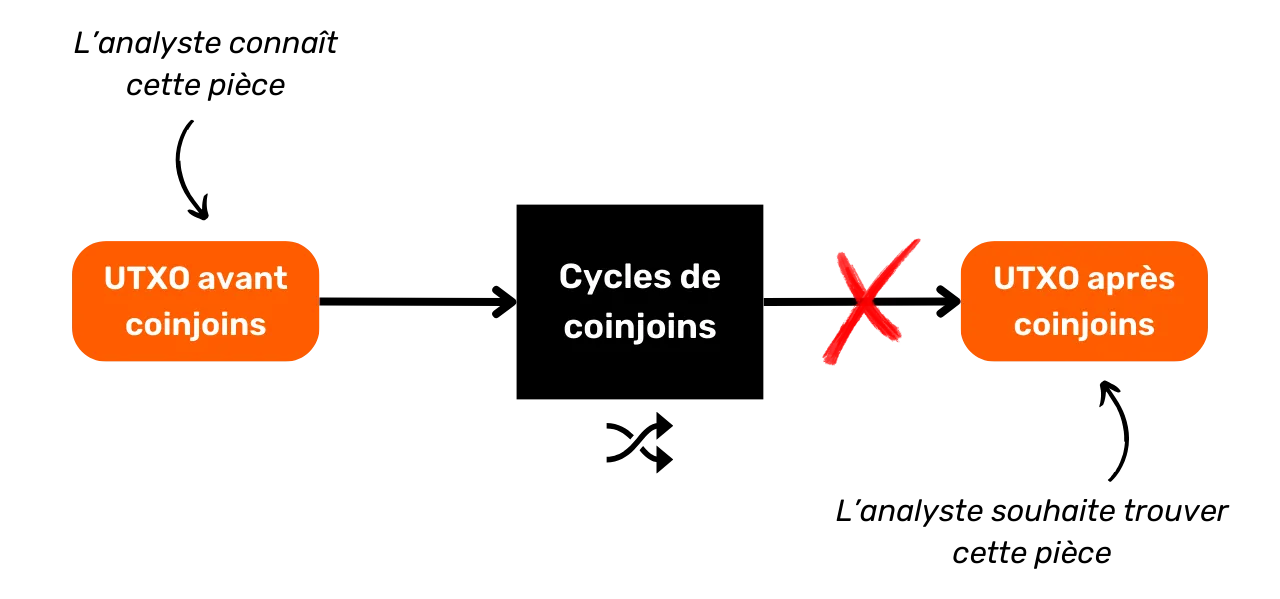

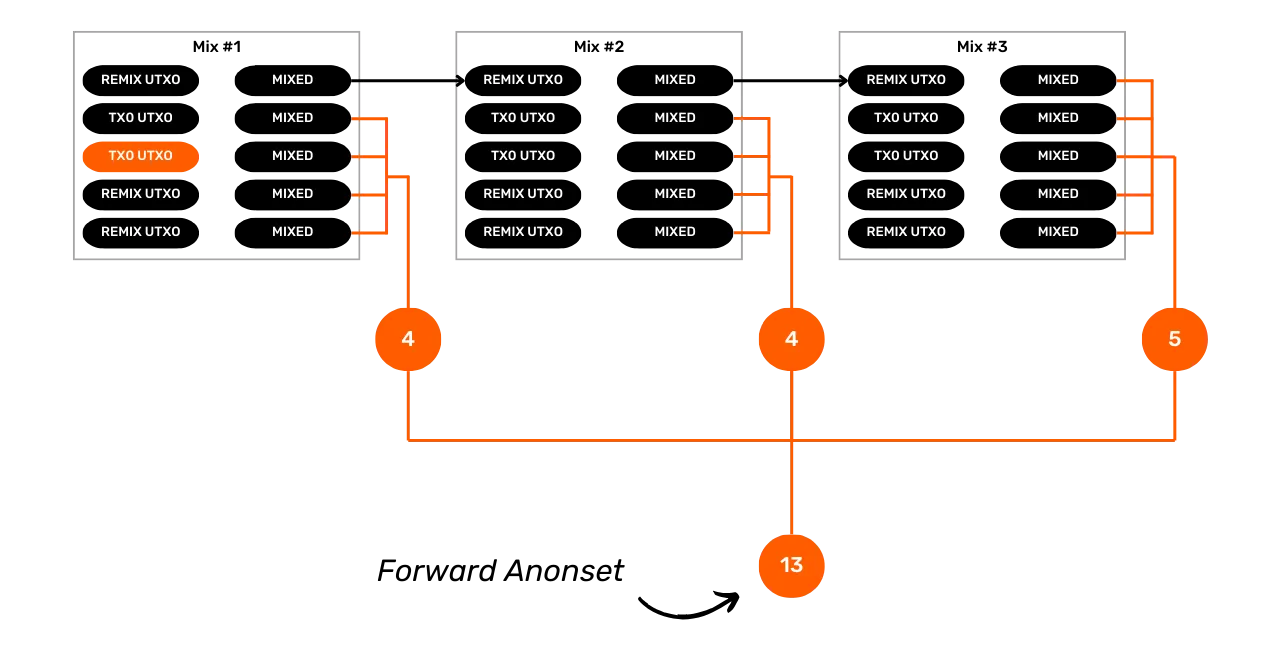

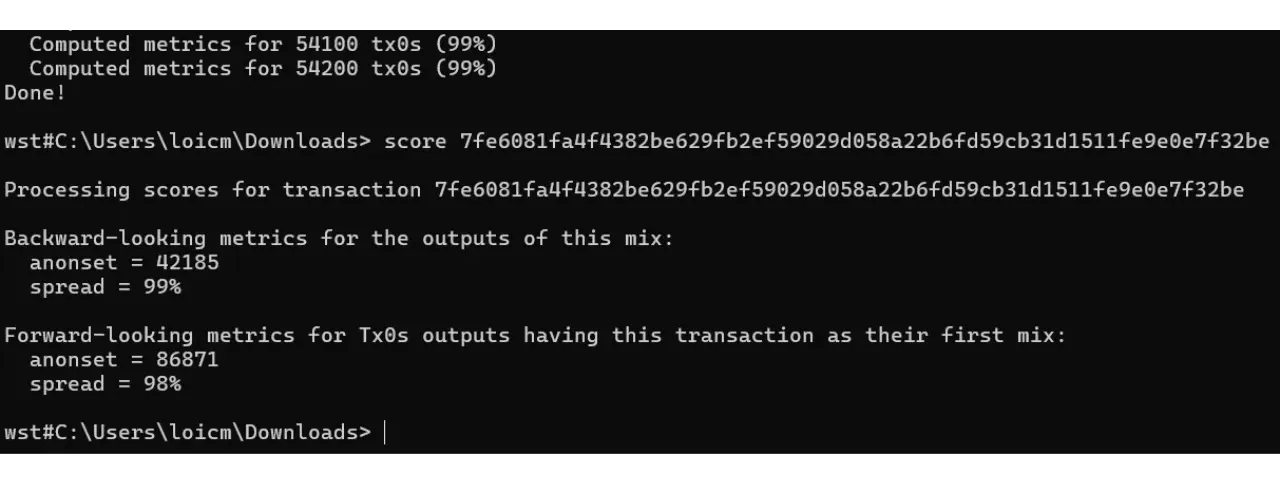

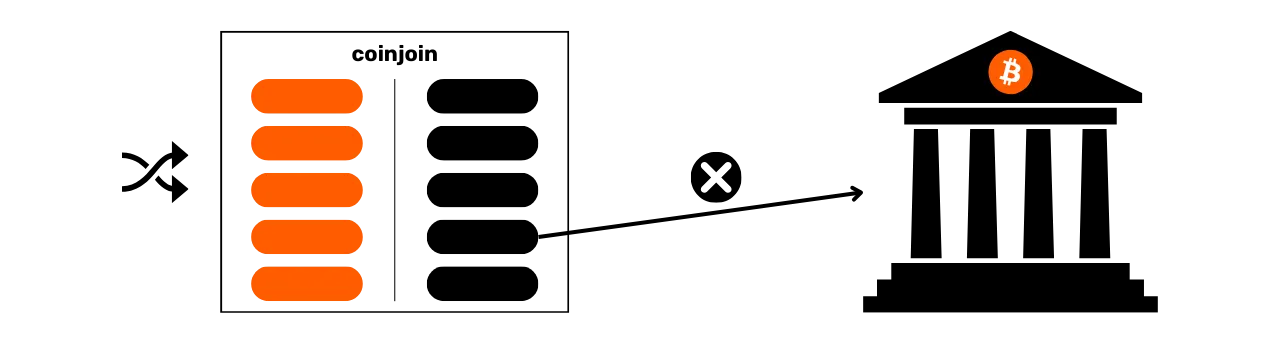

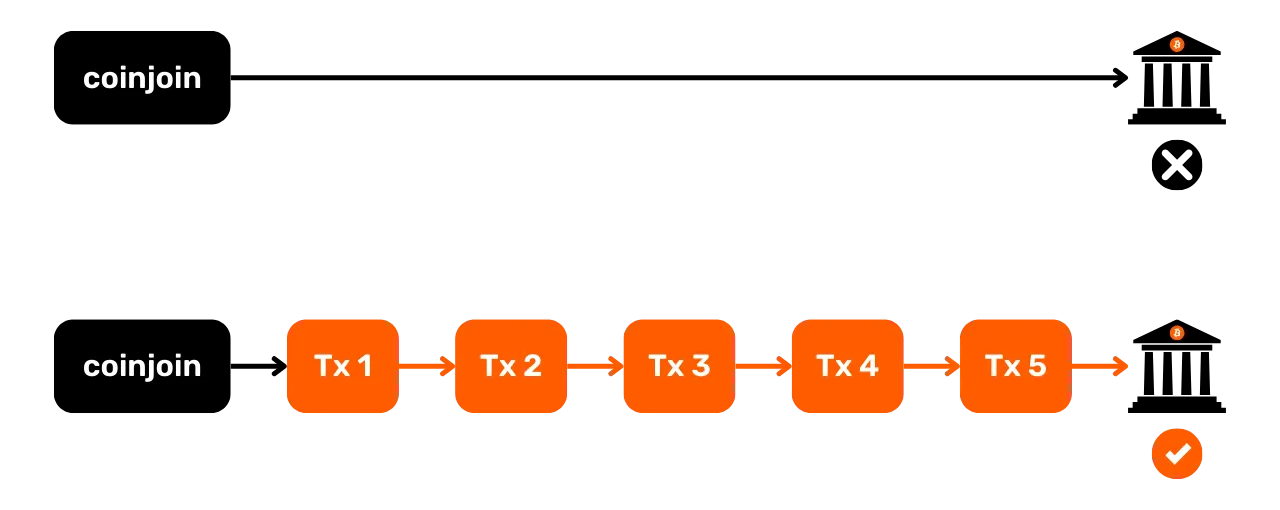

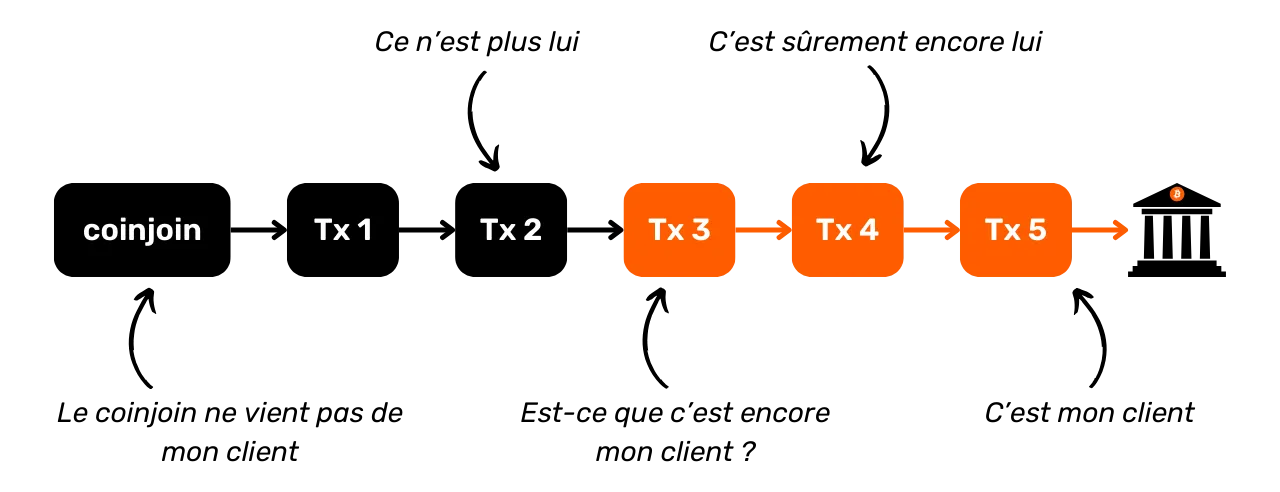

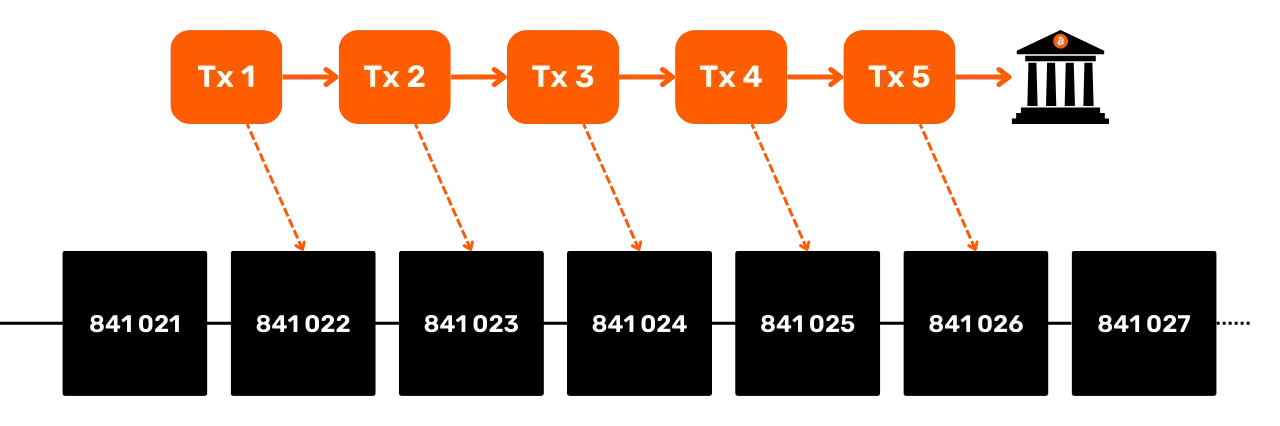

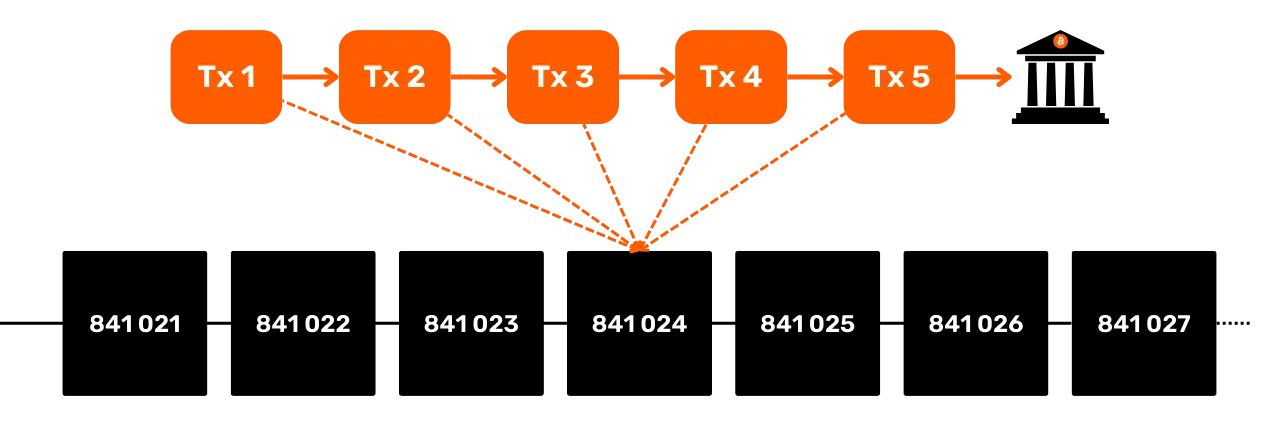

Section 4: Understanding coinjoin transactions

How can we talk about privacy on Bitcoin without mentioning coinjoins? In section 4, you'll find out all you need to know about this mixing method. You'll learn what coinjoins are, their history and objectives, as well as the different types of coinjoin that exist. Finally, for the more experienced user, we'll take a look at what anonsets and entropy are, and how to calculate them.

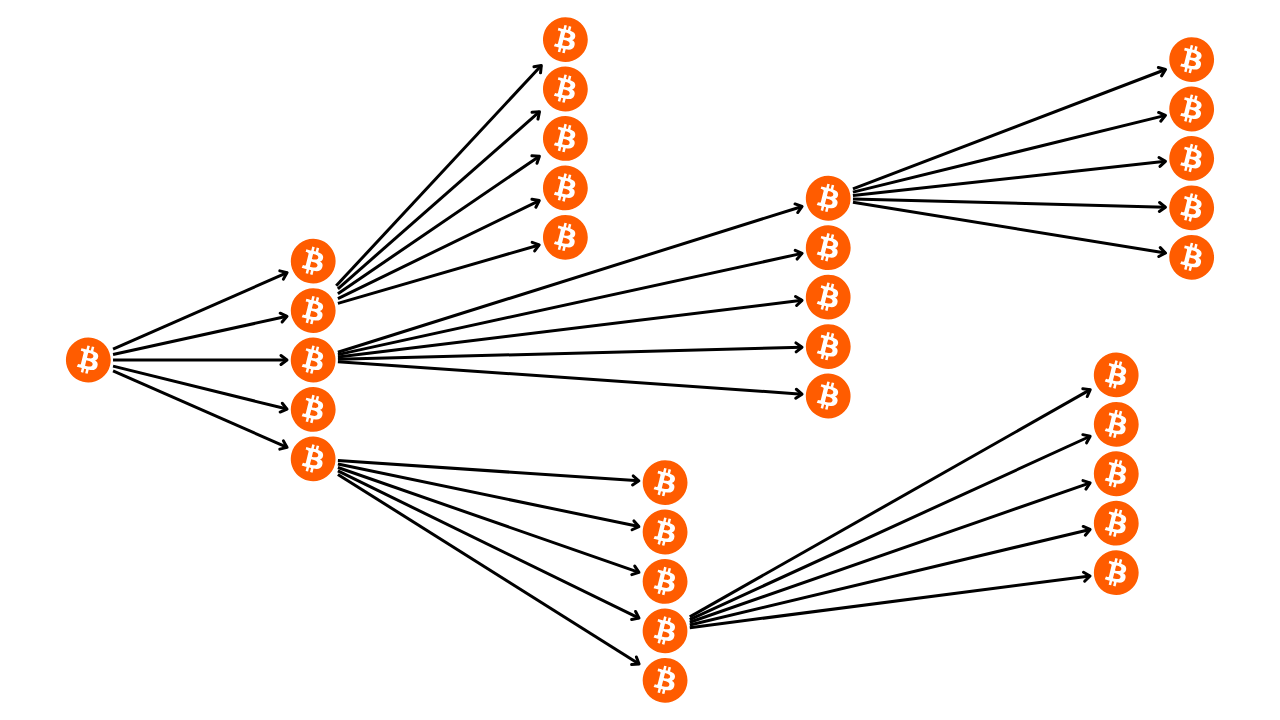

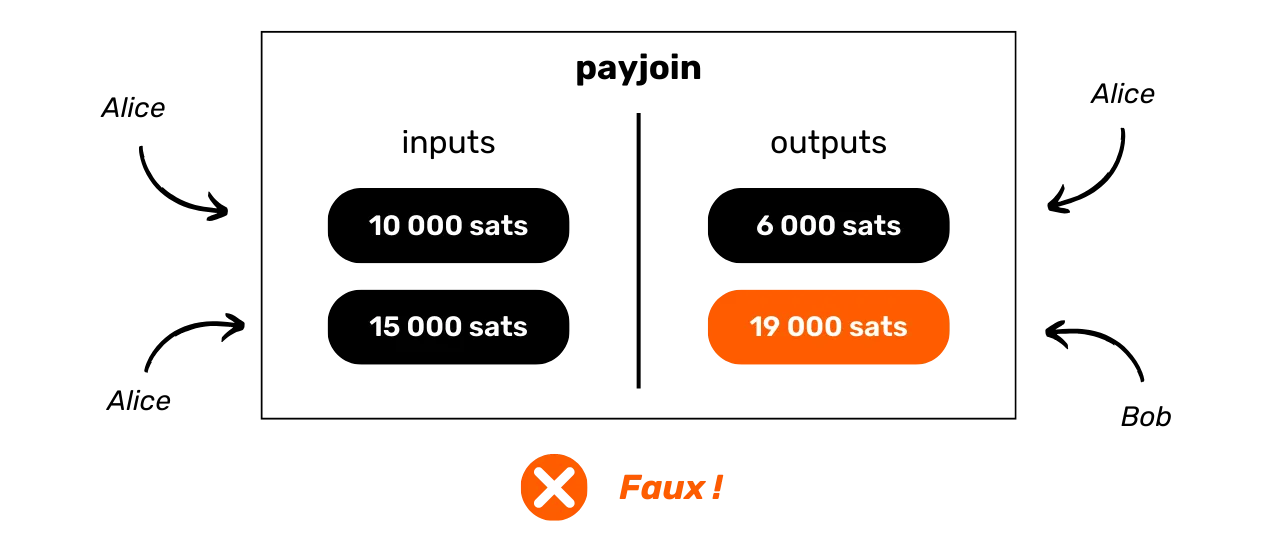

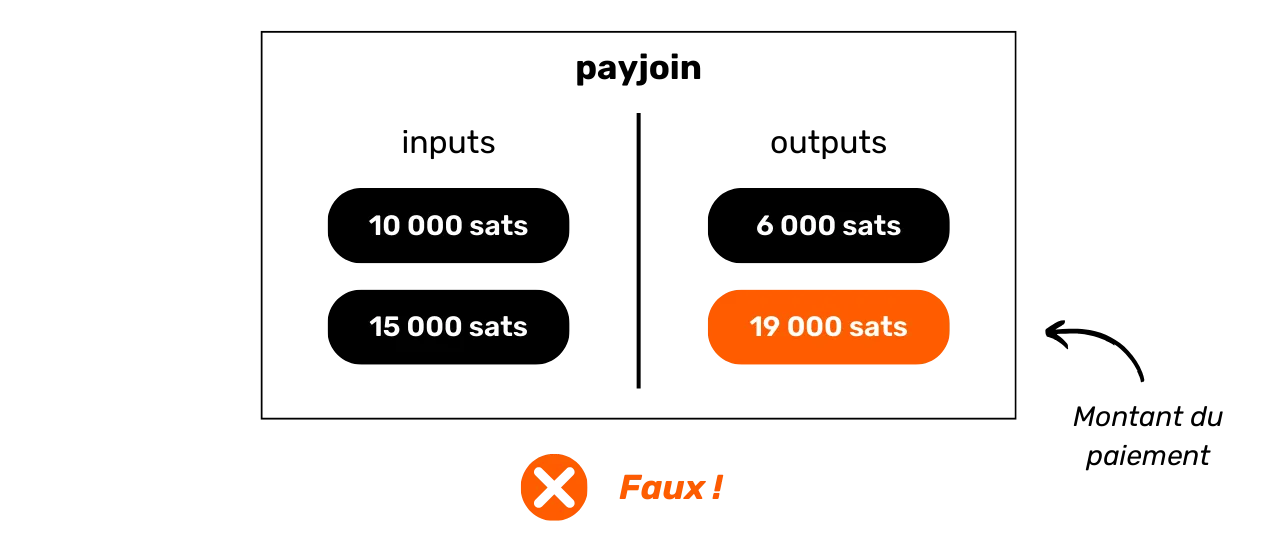

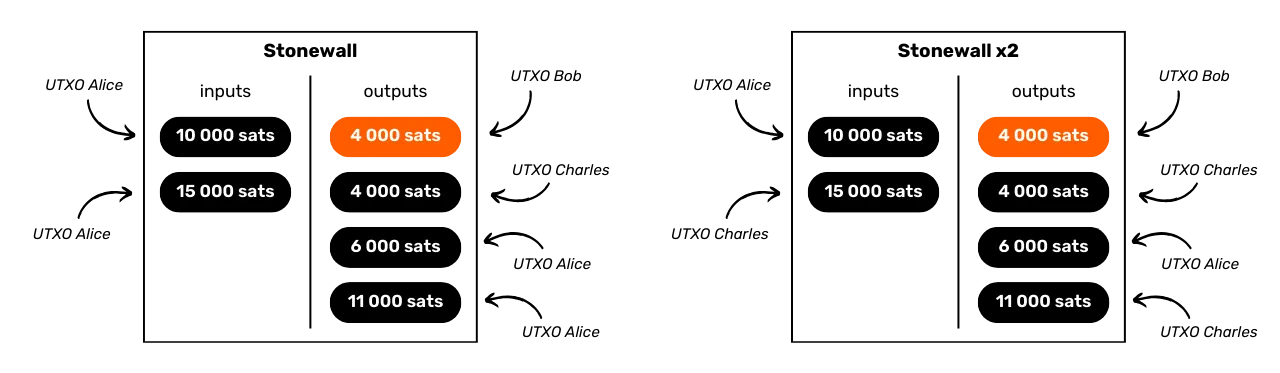

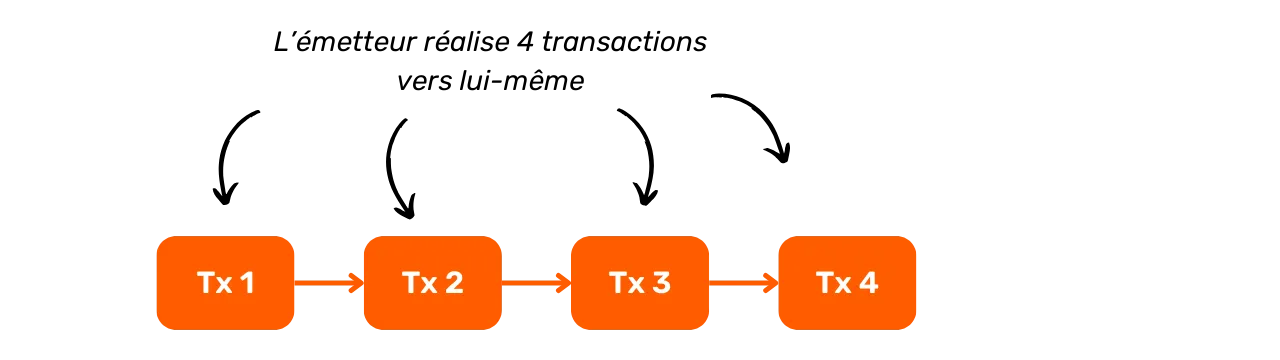

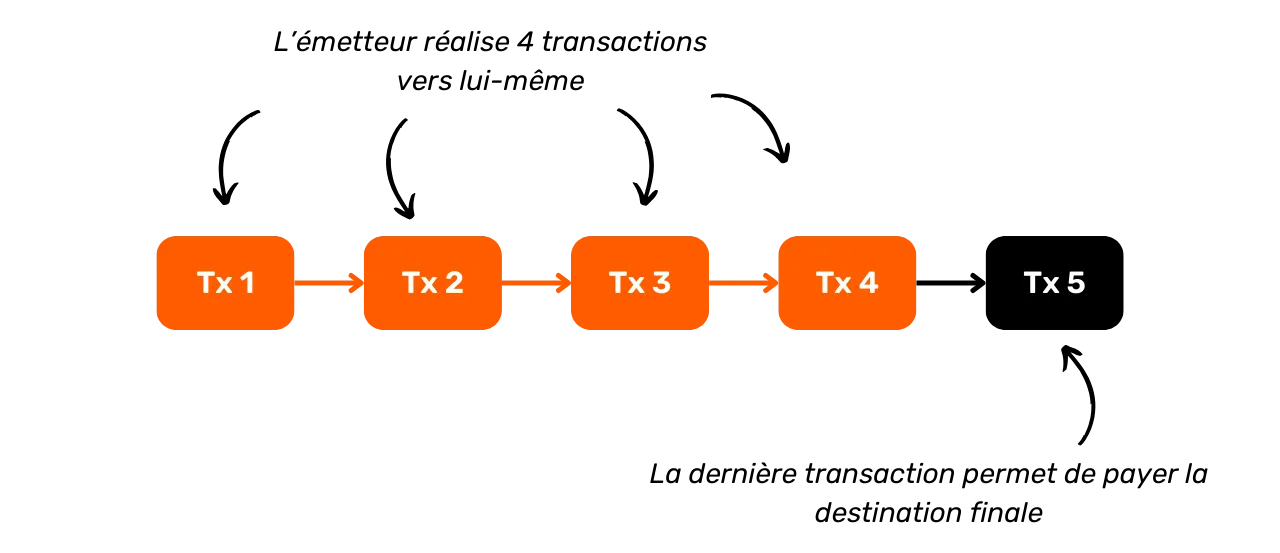

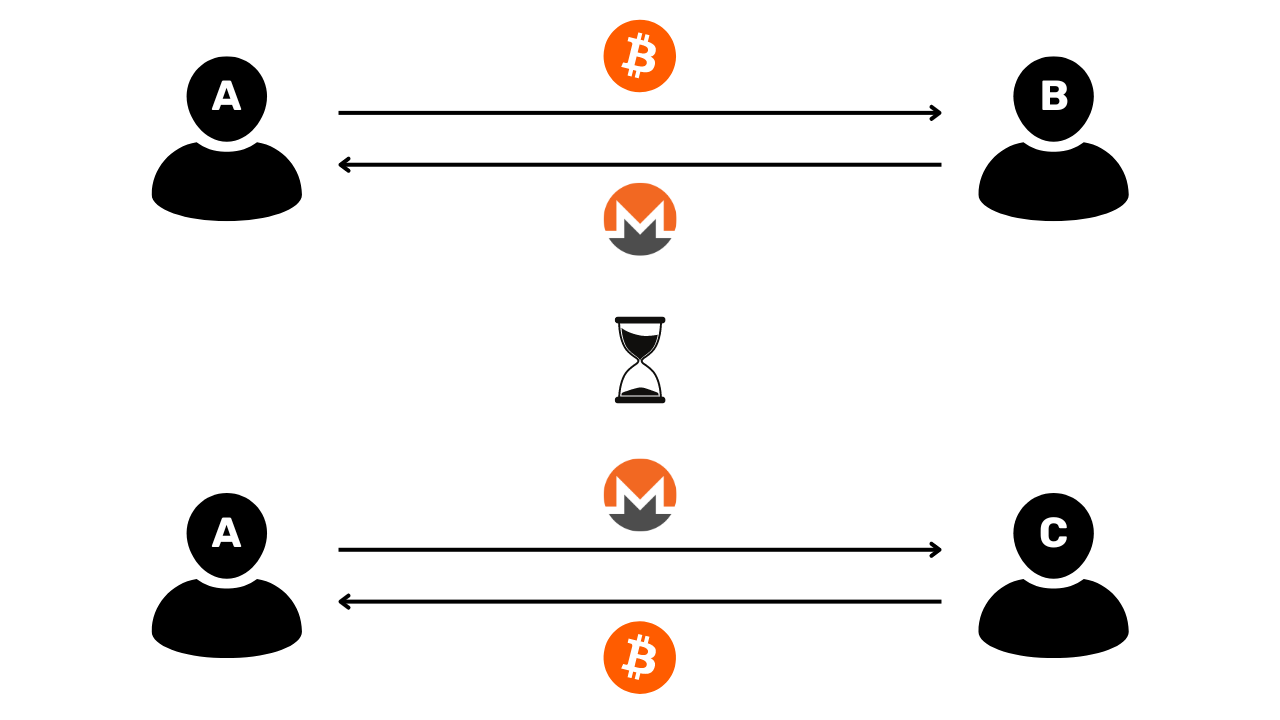

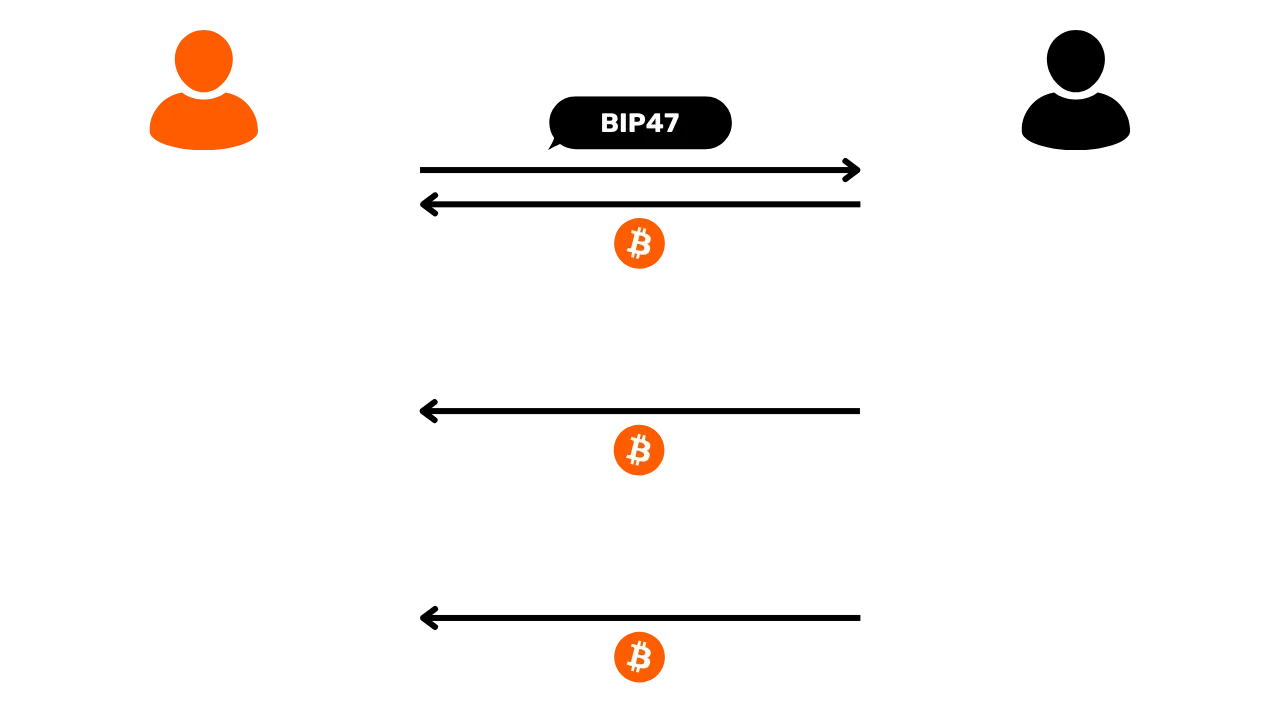

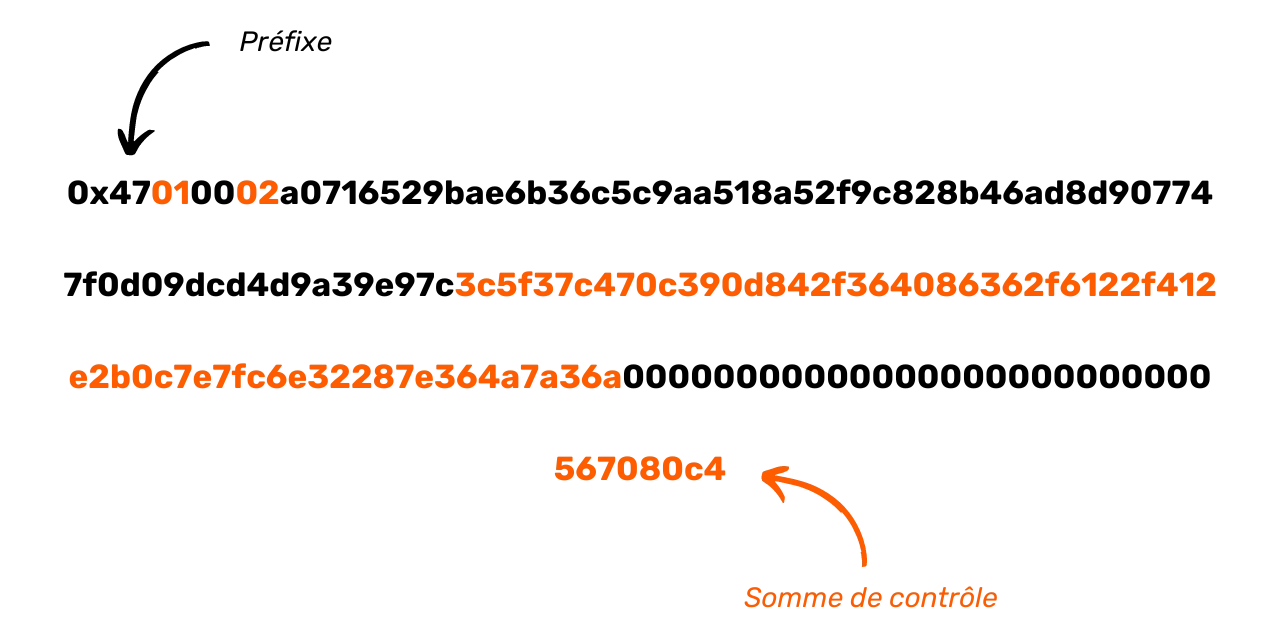

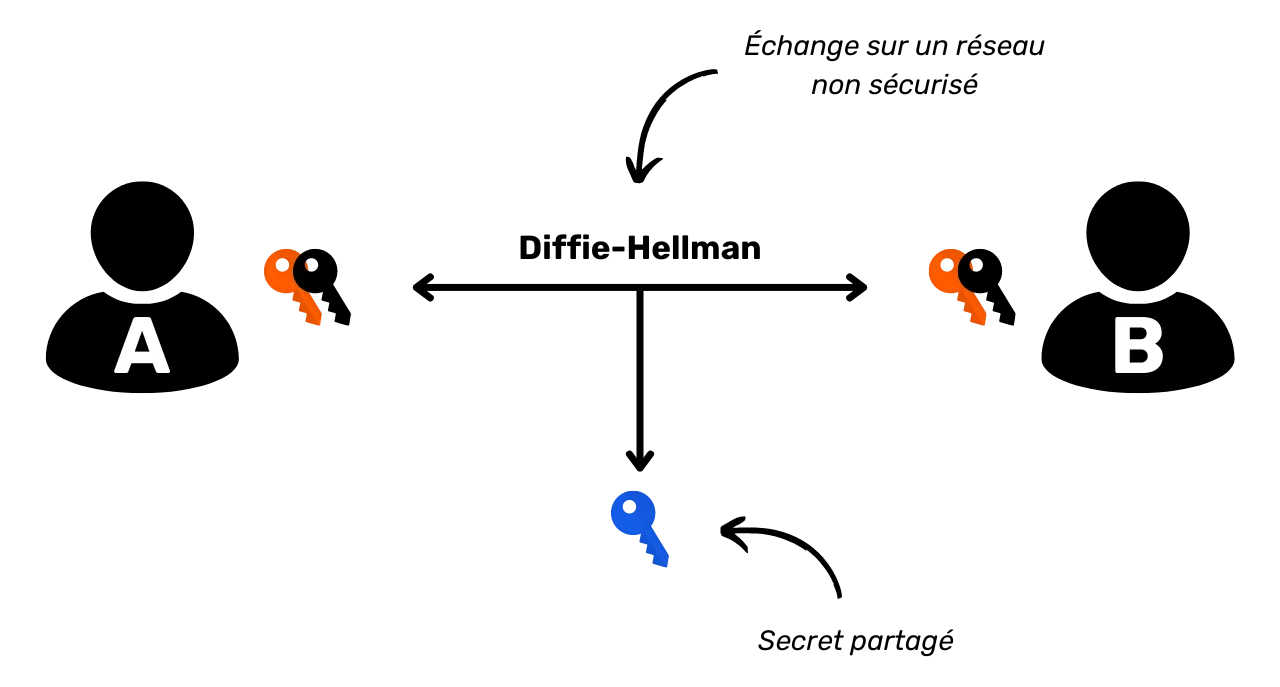

Section 5: Understanding the challenges of other advanced confidentiality techniques

In the fifth section, we'll take a look at all the other techniques available to protect your privacy on Bitcoin, apart from coinjoin. Over the years, developers have shown remarkable creativity in designing tools dedicated to privacy. We'll look at all these methods, such as payjoin, collaborative transactions, Coin Swap and Atomic Swap, detailing how they work, their objectives and any weaknesses.

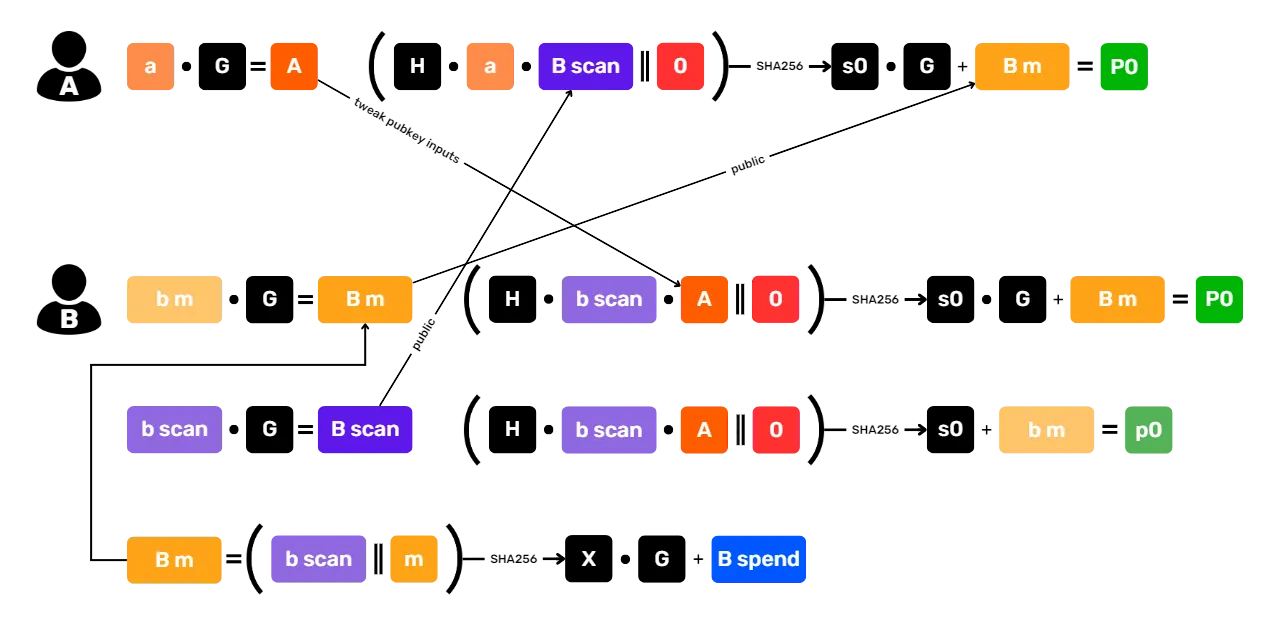

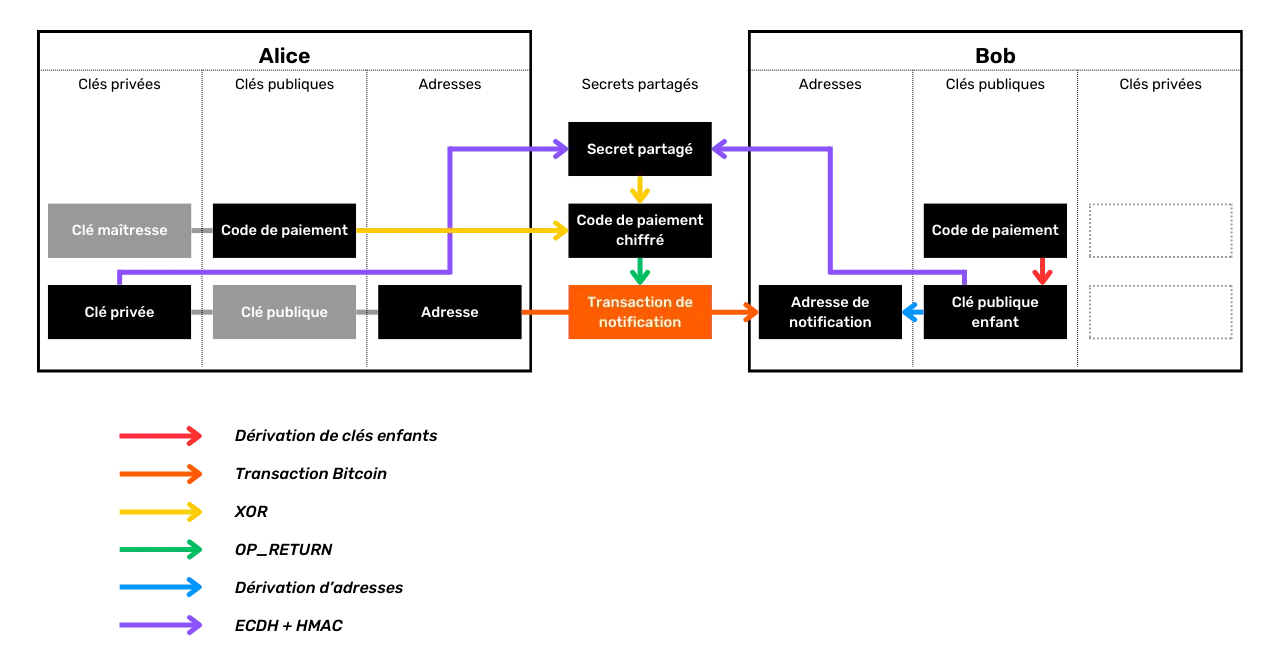

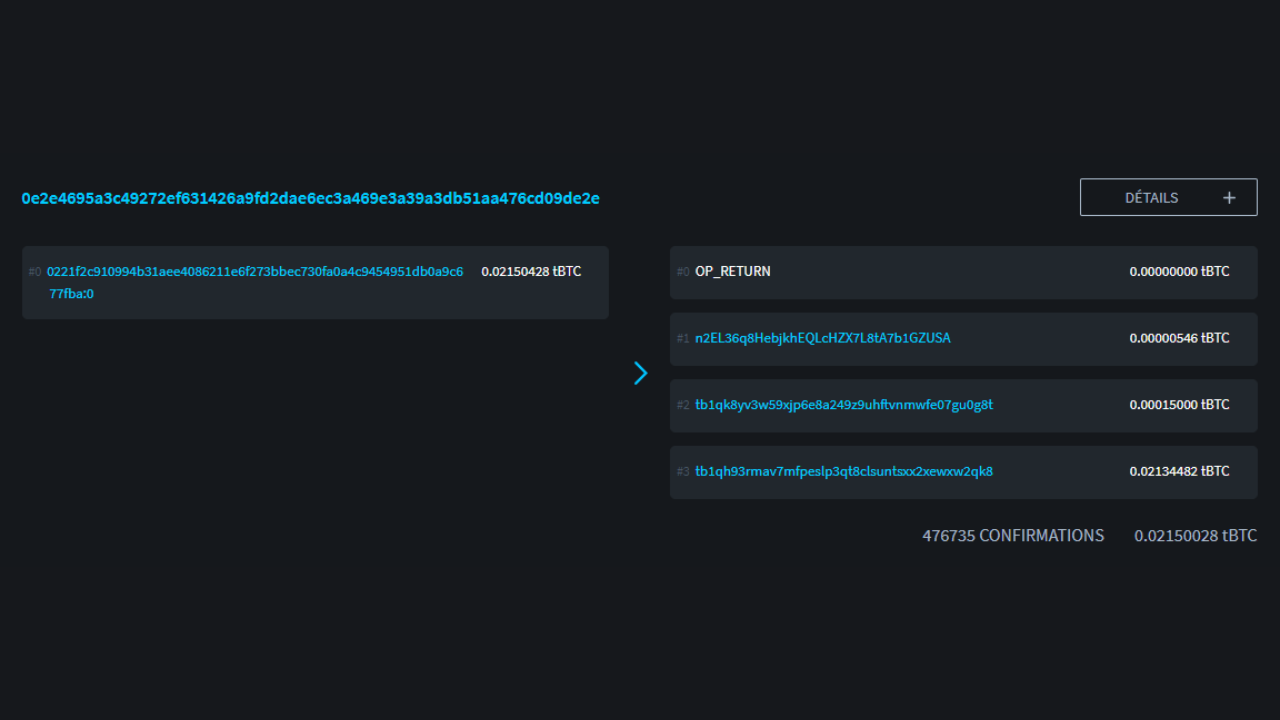

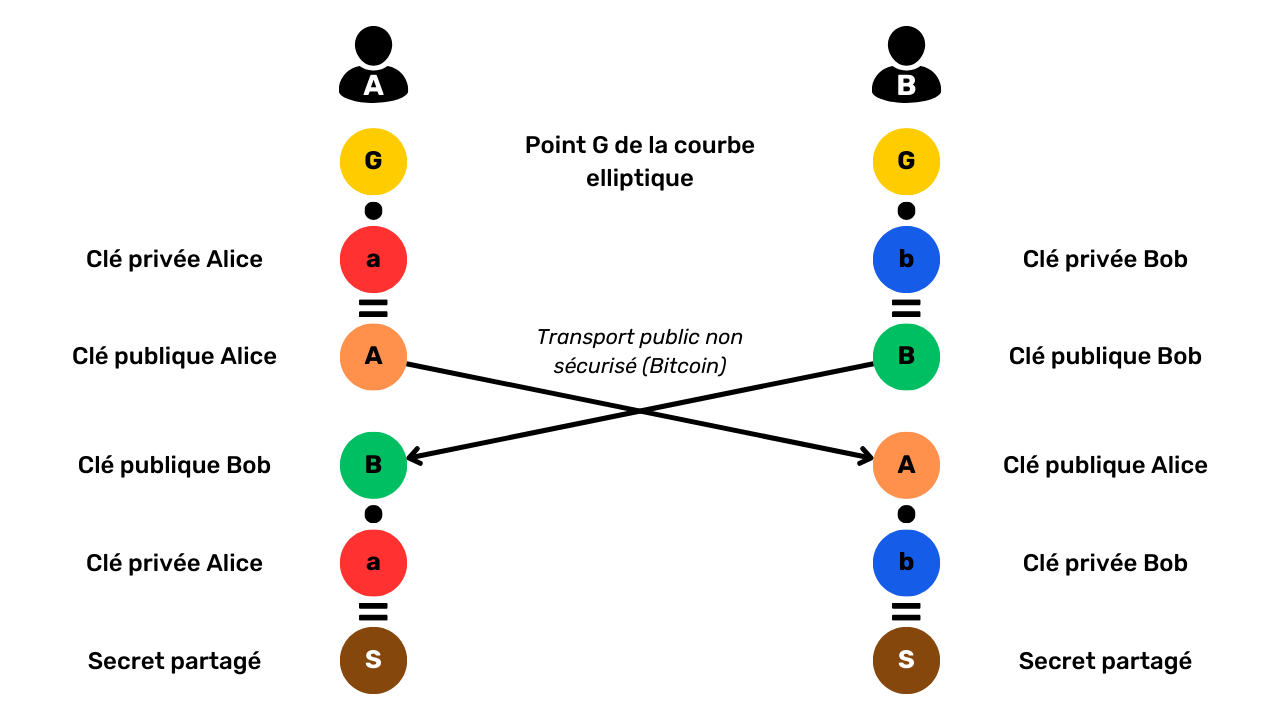

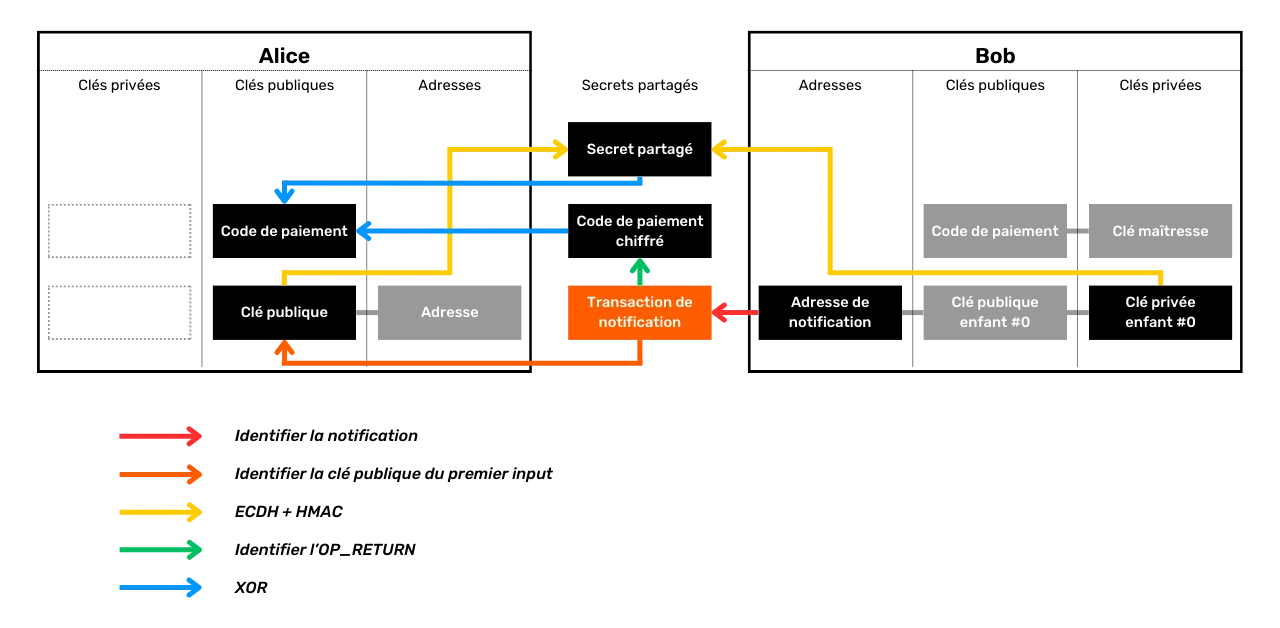

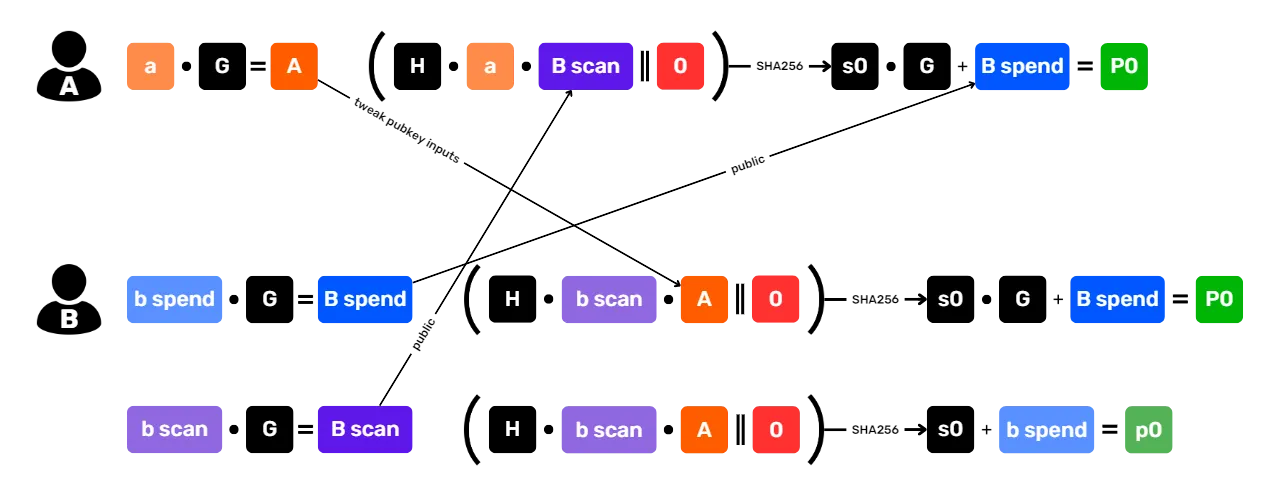

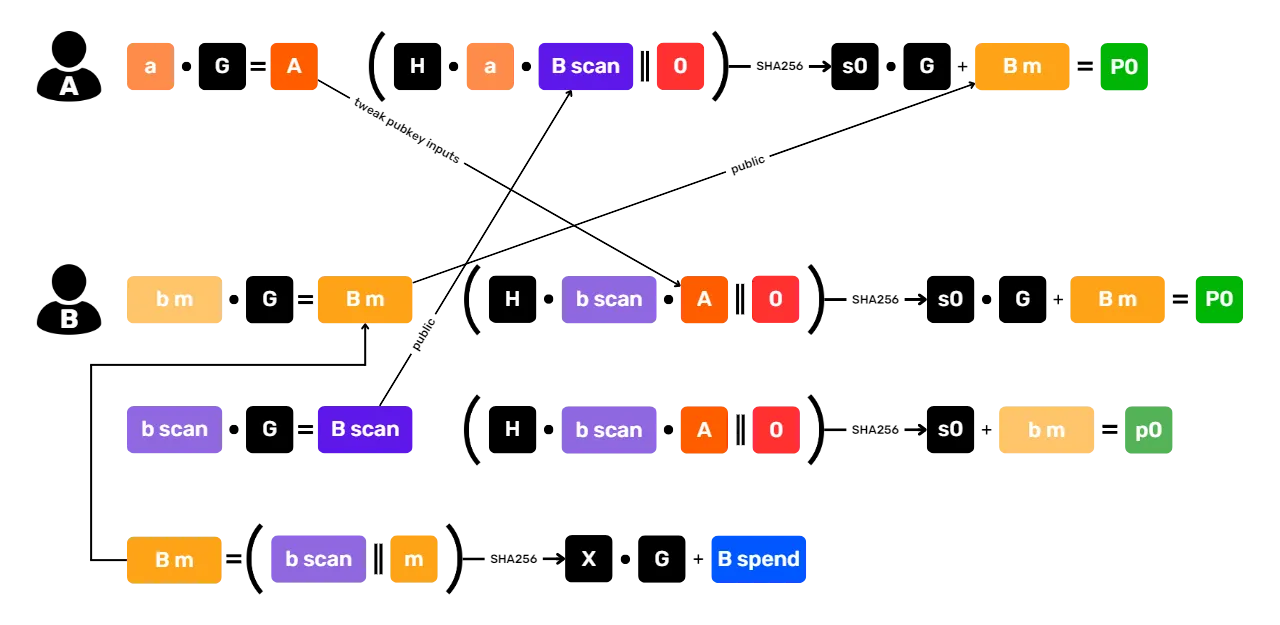

We'll also look at privacy at the level of the network of nodes and transaction dissemination. We'll also discuss the various protocols that have been proposed over the years to enhance user privacy on Bitcoin, including static address protocols.

Ready to explore the intricacies of privacy on Bitcoin? Let's go!

Ready to explore the intricacies of privacy on Bitcoin? Let's go!

Definitions and key concepts

Bitcoin's UTXO model

Bitcoin is first and foremost a currency, but do you actually know how BTC are represented on the protocol?

UTXOs on Bitcoin: what are they?

The Bitcoin protocol is based on the UTXO model, which stands for "Unspent Transaction Output".

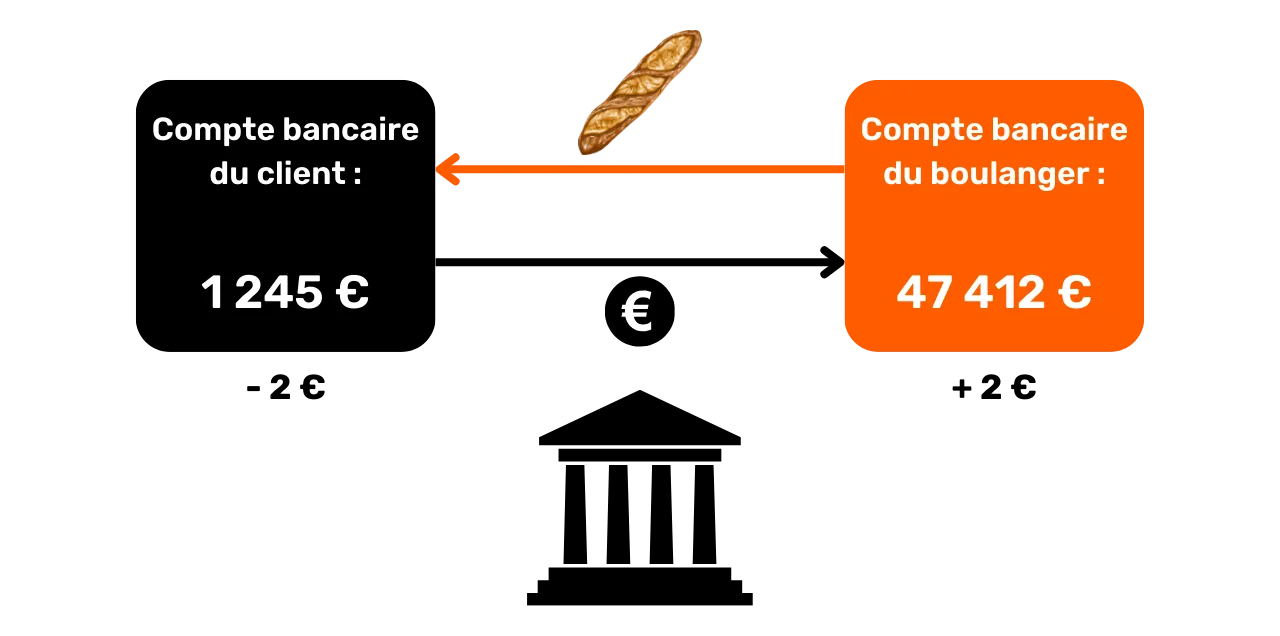

This model differs profoundly from traditional banking systems, which rely on a mechanism of accounts and balances to track financial flows. Indeed, in the banking system, individual balances are maintained in accounts attached to an identity. For example, when you buy a baguette from a baker, your bank simply debits the purchase amount from your account, reducing your balance, while the baker's account is credited with the same amount, increasing its balance. In this system, there is no notion of a link between the money entering your account and the money leaving it, apart from transaction records.

Bitcoin works differently. The concept of an account does not exist, and

monetary units are not managed via balances, but through UTXOs. A UTXO

represents a specific quantity of bitcoins that has not yet been spent, thus

forming a "piece of bitcoin", which can be large or small. For example, one

UTXO could be worth 500 BTC or simply 700 SATS.

**> The satoshi, often abbreviated to sat, is Bitcoin's smallest unit, comparable to the centime in fiat currencies.

1 BTC = 100 000 000 SATS

Theoretically, one UTXO can represent any value in bitcoins, ranging from a sat to a theoretical maximum of around 21 million BTC. However, it is logically impossible to own all 21 million bitcoins, and there is a lower economic threshold called "dust", below which a UTXO is considered economically unprofitable to spend.

**> The largest UTXO ever created on Bitcoin had a value of 500,000 BTC. It was created by the MtGox platform during a consolidation operation in

November 2011: 29a3efd3ef04f9153d47a990bd7b048a4b2d213daaa5fb8ed670fb85f13bdbcf

UTXOs and spending conditions

UTXOs are the instruments of exchange on Bitcoin. Each transaction results in the consumption of UTXOs as inputs and the creation of new UTXOs as outputs. When a transaction is completed, the UTXOs used as inputs are considered "spent", and new UTXOs are generated and allocated to the recipients indicated in the transaction outputs. Thus, a UTXO simply represents an unspent transaction output, and therefore a quantity of bitcoins belonging to a user at a given time.

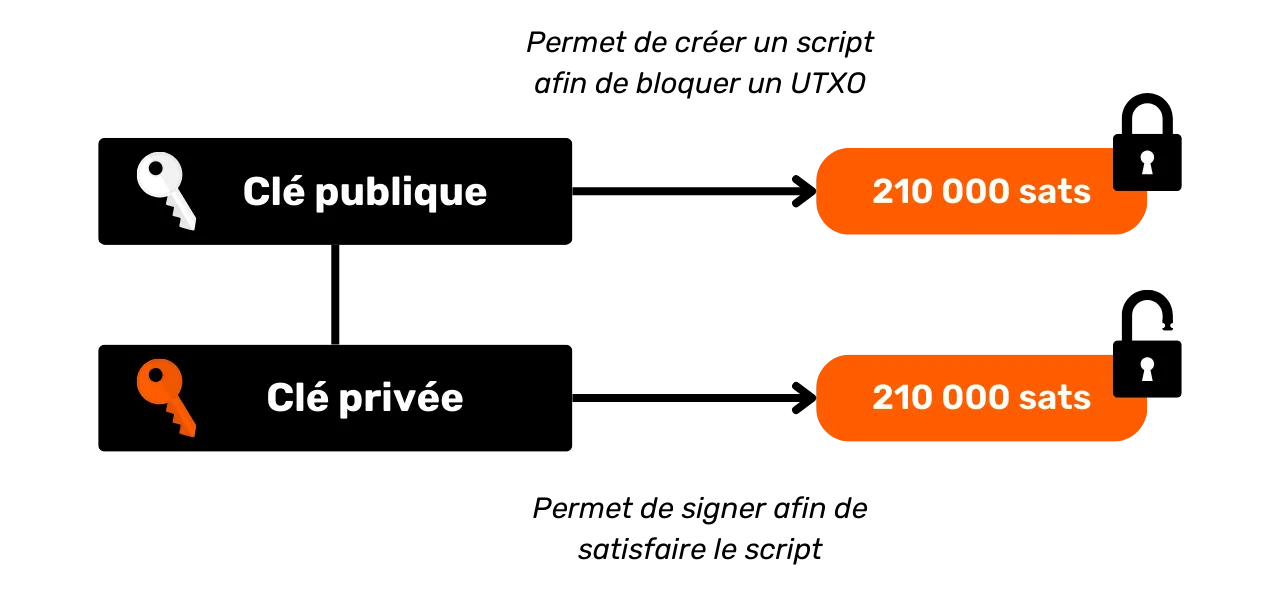

All UTXOs are secured by scripts that define the conditions under which they can be spent. To consume a UTXO, a user must demonstrate to the network that he or she satisfies the conditions stipulated by the script securing that UTXO. Typically, UTXOs are protected by a public key (or a receiving address that represents this public key). To spend a UTXO associated with this public key, the user must prove that he holds the corresponding private key, by providing a digital signature made with this key. This is why we say that your Bitcoin wallet doesn't actually contain bitcoins, but stores your private keys, which in turn give you access to your UTXOs and, by extension, to the bitcoins they represent.

Since there's no concept of an account in Bitcoin, a wallet's balance is simply the sum of the values of all the UTXOs it can spend. For example, if your Bitcoin wallet can spend the following 4 UTXOs:

- 2 BTC

- 8 BTC

- 5 BTC

- 2 BTC

The total balance of your portfolio would be 17 BTC.

The structure of Bitcoin transactions

Transaction inputs and outputs

A Bitcoin transaction is an operation recorded on the blockchain that transfers ownership of bitcoins from one person to another. More precisely, since we're on a UTXO model and there are no accounts, the transaction satisfies the spending conditions that secured one or more UTXOs, consumes them and equivalently creates new UTXOs with new spending conditions. In short, a transaction moves bitcoins from a satisfied script to a new script designed to secure them.

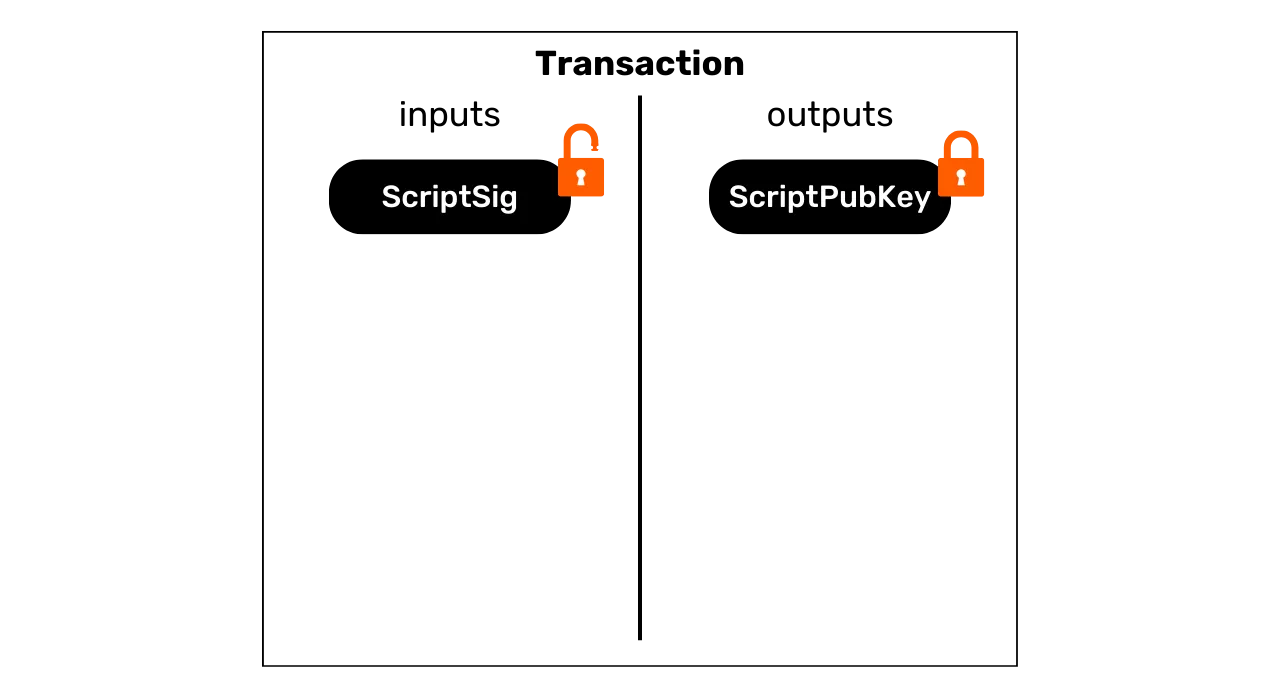

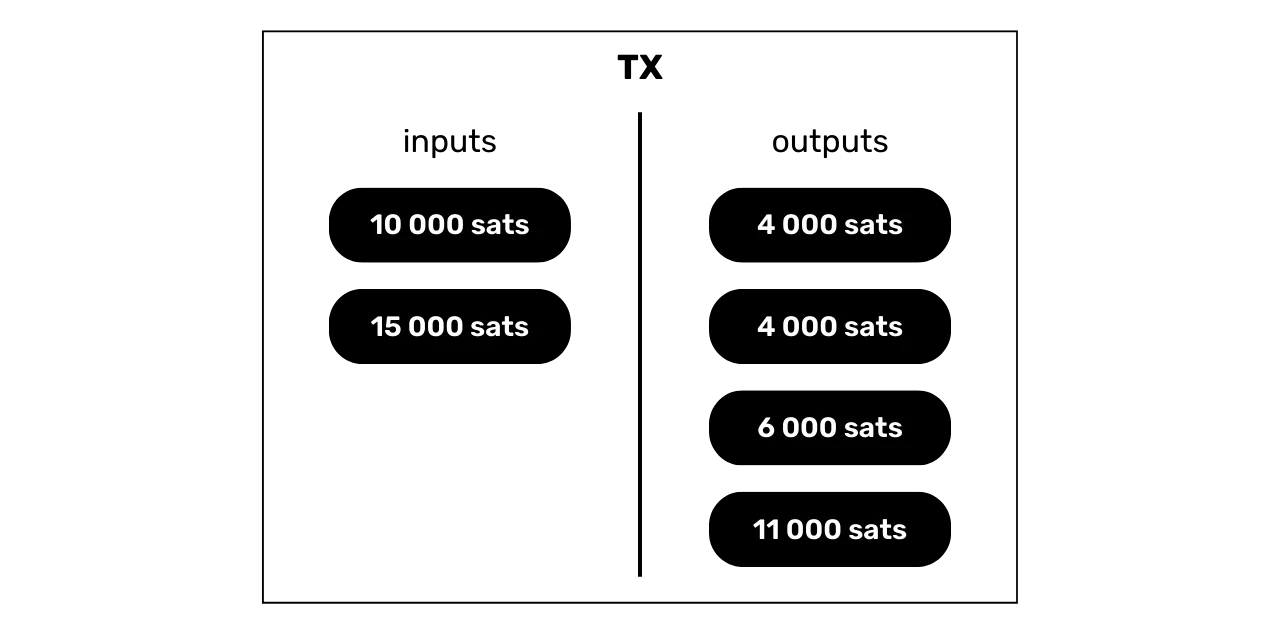

Each Bitcoin transaction therefore consists of one or more inputs and one or more outputs. Inputs are UTXOs consumed by the transaction to generate outputs. Outputs are new UTXOs that can be used as inputs for future transactions.

**> Theoretically, a bitcoin transaction could have an infinite number of inputs and outputs. The only limit is the maximum block size.

Each input in a Bitcoin transaction refers to a previous unspent UTXO. To use a UTXO as an input, its holder must demonstrate that he/she is the rightful owner by validating the associated script, i.e. by satisfying the spending condition imposed. Generally speaking, this means providing a digital signature produced with the private key corresponding to the public key that initially secured this UTXO. The script therefore consists in verifying that the signature corresponds to the public key used when the funds were received.

Each output, in turn, specifies the amount of bitcoins to be transferred, as well as the recipient. The latter is defined by a new script, which usually blocks the newly created UTXO with a receiving address or a new public key.

For a transaction to be considered valid according to the consensus rules,

total outputs must be less than or equal to total inputs. In other words,

the sum of new UTXOs generated by the transaction must not exceed the sum of

UTXOs consumed as inputs. This principle is logical: if you only have 500,000 SATS, you can't make a purchase of 700,000 SATS.

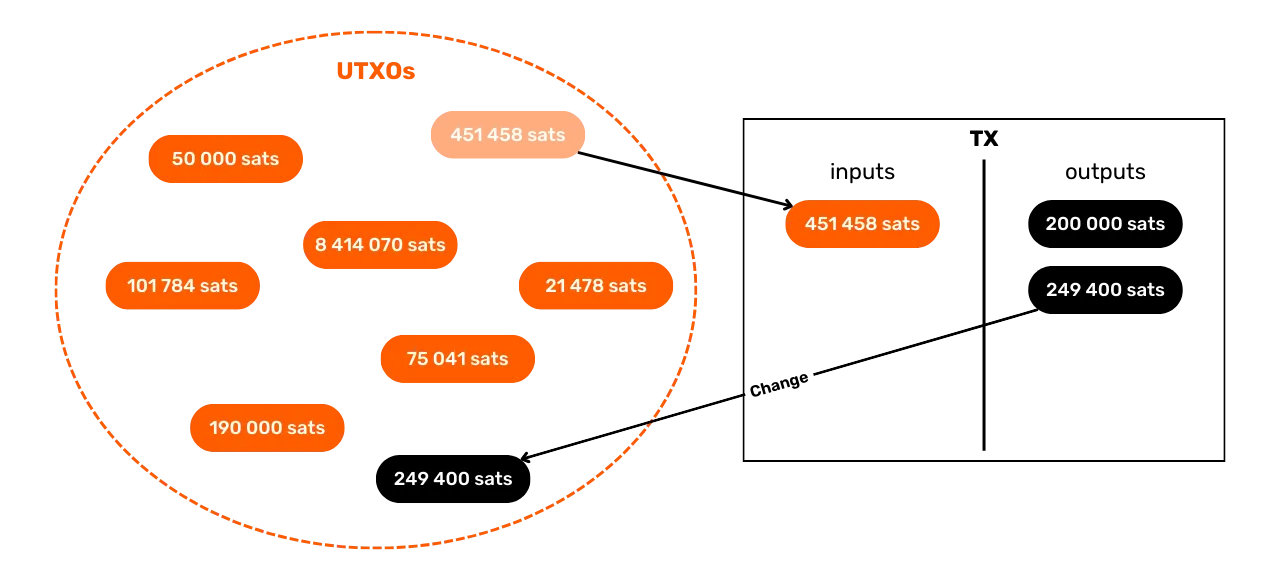

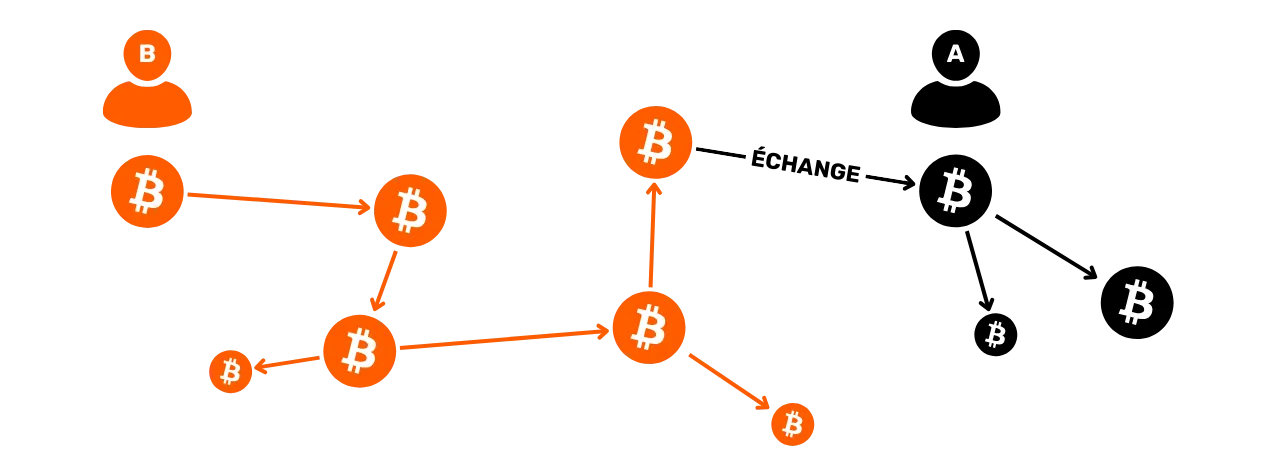

Exchange and merging in a Bitcoin transaction

The action of a Bitcoin transaction on UTXO can thus be compared to recasting a gold coin. Indeed, a UTXO is not divisible, but only fusible. This means that a user cannot simply divide a UTXO representing a certain amount in bitcoins into several smaller UTXOs. He must consume it entirely in a transaction to create one or more new UTXOs of arbitrary values in outputs, which must be less than or equal to the initial value.

This mechanism is similar to that of a gold coin. Let's say you own a 2-ounce coin and want to make a payment of 1 ounce, assuming the seller can't give you change. You would have to melt your coin and cast 2 new ones of 1 ounce each.

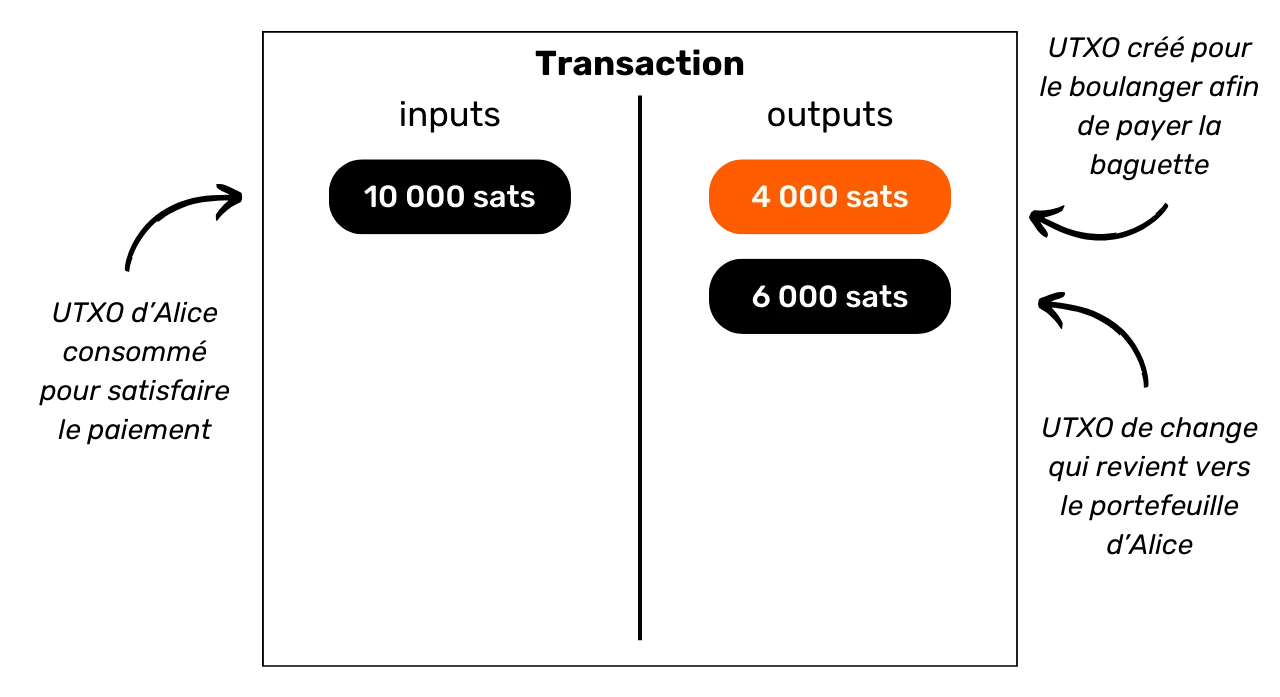

Bitcoin works in a similar way. Let's imagine that Alice has a UTXO of 10,000 SATS and wishes to buy a baguette costing 4,000 SATS. Alice will

make a transaction with 1 UTXO of 10,000 SATS as input, which

she will consume in full, and 2 UTXOs of 4,000 SATS and 6,000 SATS as output. The UTXO of 4,000 SATS will be sent to the baker in

payment for the baguette, while the UTXO of 6,000 SATS will return

to Alice in the form of change. This UTXO, which returns to the original issuer

of the transaction, is known as "exchange" in Bitcoin jargon.

Now let's imagine that Alice doesn't have a single UTXO of 10,000 SATS, but rather two UTXOs of 3,000 SATS each. In this situation,

neither of the UTXOs individually is sufficient to set the wand's 4,000 SATS. Alice must therefore simultaneously use the 2 UTXOs

of 3,000 SATS as inputs to her transaction. In this way, the

total amount of inputs will reach 6,000 SATS, enabling her to

satisfy the 4,000 SATS payment to the baker. This method, in which

several UTXOs are grouped together as inputs to a transaction, is often referred

to as "merging".

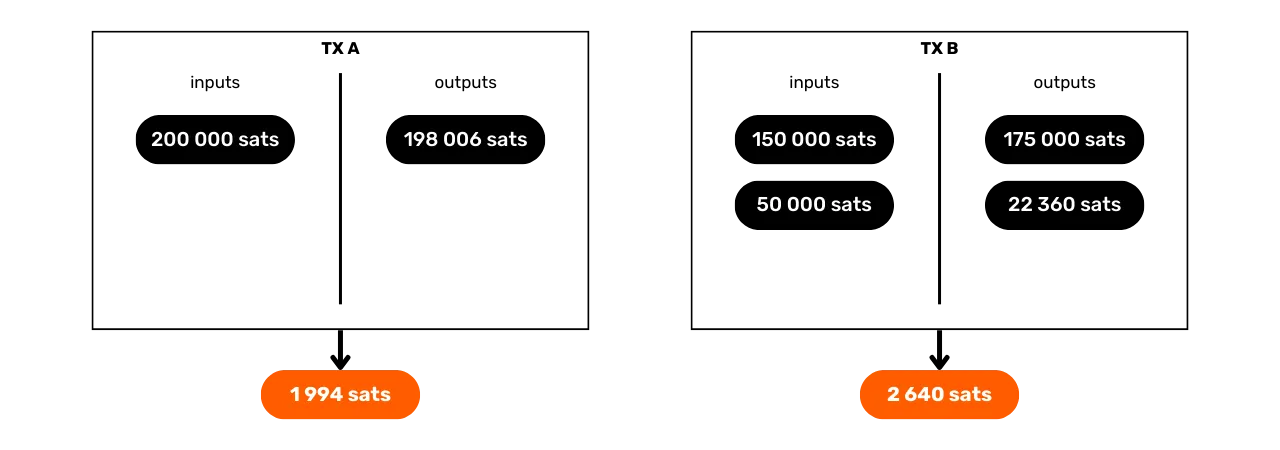

Transaction fees

Intuitively, one might think that transaction costs also represent the output of a transaction. But in reality, this is not the case. Transaction costs represent the difference between total inputs and total outputs. This means that, after using part of the value of the inputs to cover the desired outputs in a transaction, a certain sum of the inputs remains unused. This residual sum constitutes the transaction costs.

Frais = total inputs - total outputs

Let's take the example of Alice, who has a UTXO of 10,000 SATS and wants to buy a baguette at 4,000 SATS. Alice creates a

transaction with her UTXO of 10,000 SATS as input. She then

generates an output of 4,000 SATS for the baker to pay for the

baguette. To encourage miners to integrate her transaction into a block,

Alice allocates 200 SATS in fees. She then creates a second

output, the exchange, which will be returned to her, amounting to 5,800 SATS.

Applying the fee formula, we see that there are indeed 200 SATS left for minors:

Frais = total inputs - total outputs

Frais = 10 000 - (4 000 + 5 800)

Frais = 10 000 - 9 800

Frais = 200

When a miner succeeds in validating a block, he is authorized to collect these fees for all the transactions included in his block, via the so-called "coinbase" transaction.

Creating UTXOs on Bitcoin

If you've followed the previous paragraphs carefully, you'll now know that UTXOs can only be created by consuming other existing UTXOs. In this way, Bitcoin coins form a continuous chain. However, you may be wondering how the first UTXOs in this chain came about. This raises a problem similar to that of the chicken and the egg: where did these original UTXOs come from?

The answer is in the transaction coinbase.

The coinbase is a specific type of Bitcoin transaction, which is unique for each block and is always the first of these. It allows the miner who has found a valid proof of work to receive his block reward. This reward is made up of two elements: block grant and transaction fee, discussed in the previous section.

The coinbase transaction is unique in that it is the only one capable of creating bitcoins ex nihilo, without the need to consume inputs to generate outputs. These newly-created bitcoins are what we might call "original UTXOs".

Block-subsidized bitcoins are new BTC created from scratch, according to a pre-established issuance schedule in the consensus rules. The block grant is halved every 210,000 blocks, i.e. approximately every four years, in a process known as "halving". Originally, 50 bitcoins were created with each subsidy, but this amount has gradually decreased; currently, it is 3.125 bitcoins per block.

As for transaction fees, although they also represent newly created BTC, they must not exceed the difference between the total inputs and outputs of all transactions in a block. We saw earlier that these fees represent the portion of inputs that is not used in transaction outputs. This portion is technically "lost" during the transaction, and the miner has the right to recreate this value in the form of one or more new UTXOs. This is a transfer of value between the issuer of the transaction and the miner who adds it to the blockchain.

**> Bitcoins generated by a coinbase transaction are subject to a maturity period of 100 blocks, during which they cannot be spent by the miner. This rule is designed to avoid complications linked to the use of newly created bitcoins on a chain that could later be rendered obsolete.

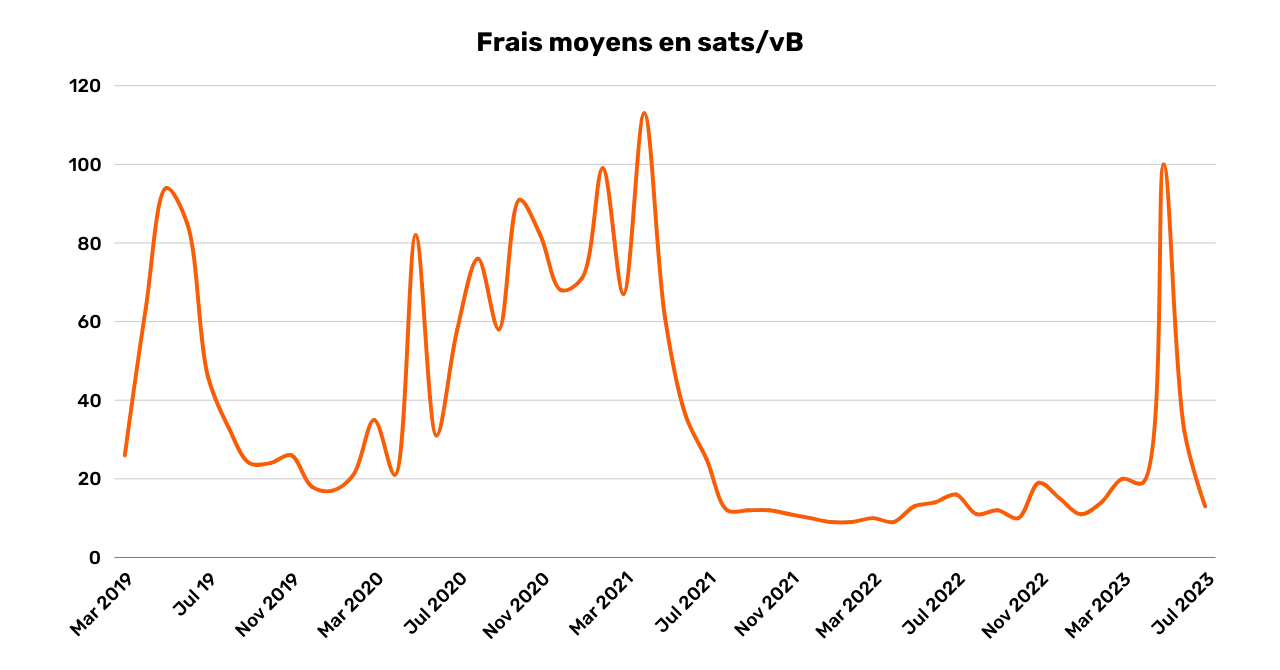

The implications of the UTXO model

First of all, the UTXO model directly influences Bitcoin's transaction fees. Since the capacity of each block is limited, miners favor transactions that offer the best fees in relation to the space they will take up in the block. Indeed, the more UTXOs a transaction includes in its inputs and outputs, the heavier it is, and therefore requires higher fees. This is one of the reasons why we often try to reduce the number of UTXOs in our portfolio, which can also affect confidentiality, a subject we'll be tackling in detail in the third part of this course.

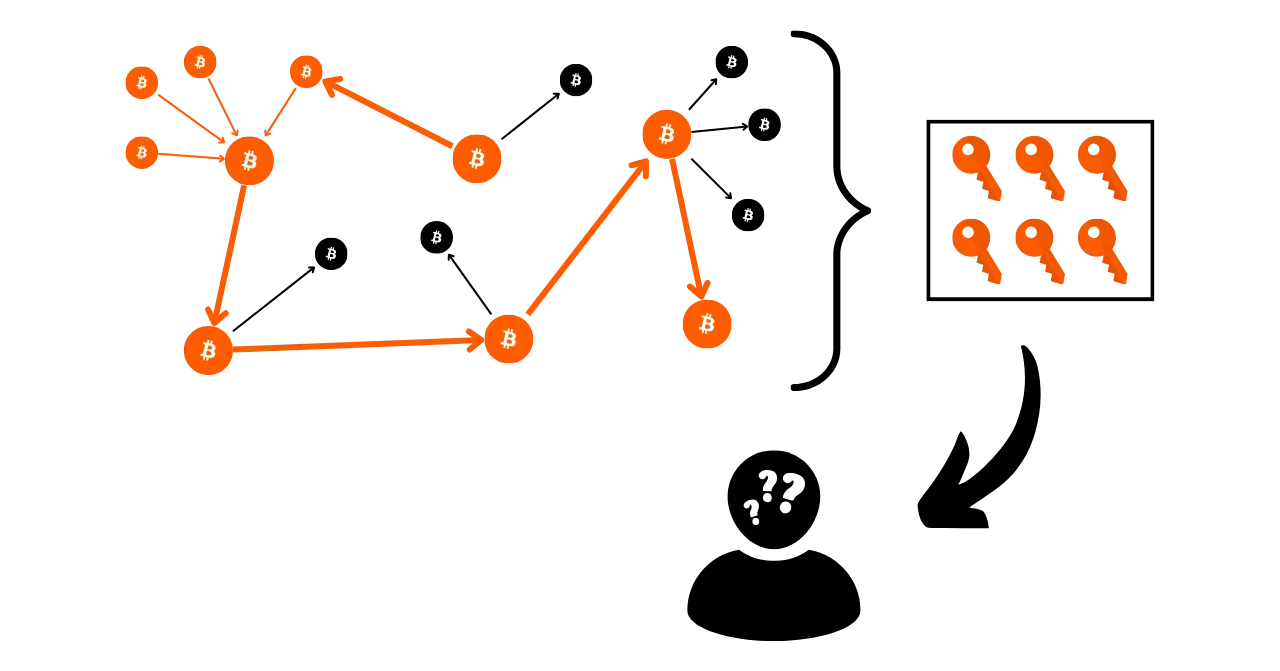

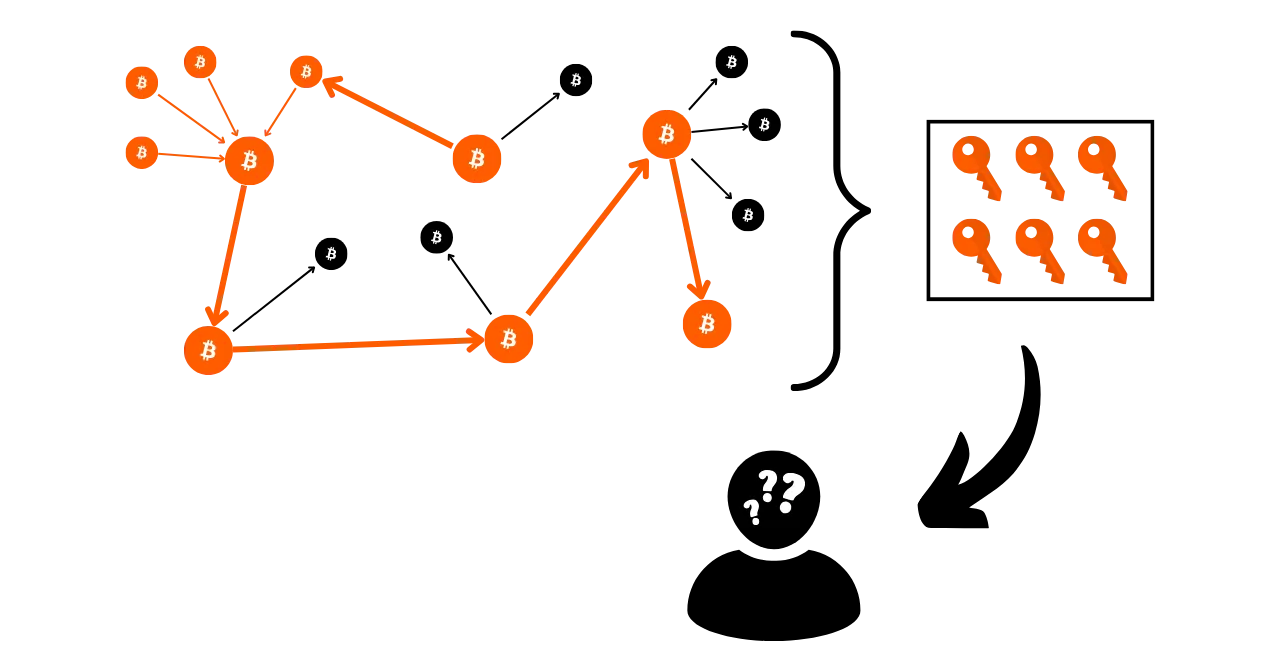

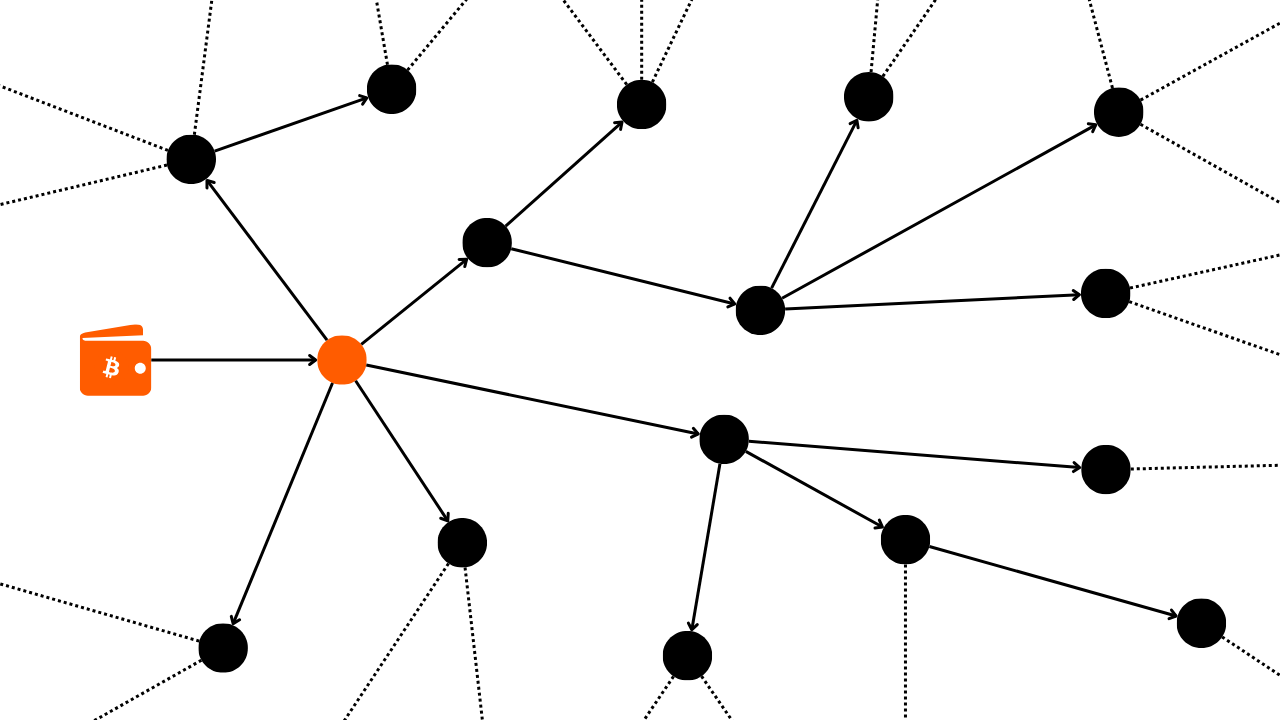

Secondly, as mentioned in the previous sections, Bitcoin coins are essentially a chain of UTXOs. Each transaction thus creates a link between a past UTXO and a future UTXO. UTXOs therefore make it possible to explicitly follow the path of Bitcoins from their creation to their current expenditure. This transparency can be viewed positively, as it enables each user to ascertain the authenticity of the bitcoins received. However, it is also on this principle of traceability and auditability that blockchain analysis is based, a practice designed to compromise your confidentiality. We'll be taking an in-depth look at this practice in the second part of the course.

Bitcoin's privacy model

Money: authenticity, integrity and double spending

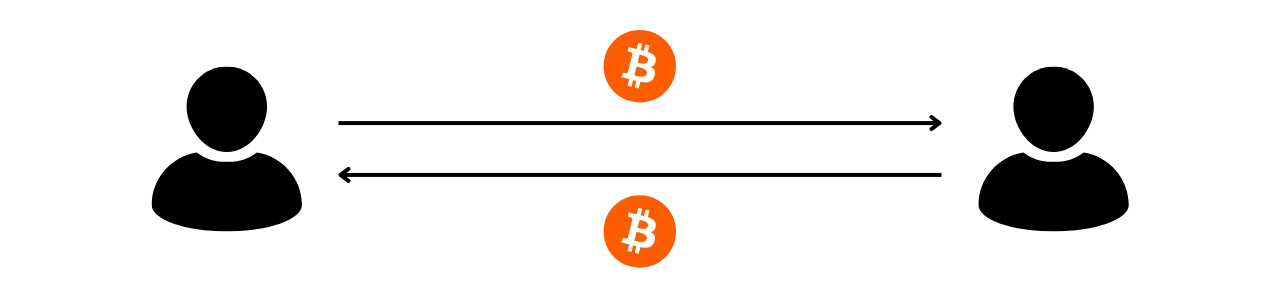

One of the functions of money is to solve the problem of the double coincidence of needs. In a system based on bartering, the completion of an exchange requires not only finding an individual who is giving away a good corresponding to my need, but also providing him with a good of equivalent value that satisfies his own need. Striking this balance is a complex matter.

That's why we use money to move value in both space and time.

For coinage to solve this problem, it is essential that the party providing a good or service is convinced of its ability to spend that sum at a later date. Thus, any rational individual wishing to accept a coin, whether digital or physical, will ensure that it meets two fundamental criteria:

- The piece must have integrity and authenticity ;**

- and must not be double-spent.**

If you're using physical currency, it's the first characteristic that's the most complex to assert. At different periods in history, the integrity of metal coins has often been affected by practices such as trimming or piercing. In ancient Rome, for example, it was common practice for citizens to scrape the edges of gold coins to collect a little precious metal, while saving them for future transactions. The intrinsic value of the coin was thus reduced, but its face value remained the same. This is one of the reasons why the edge of the coin was later fluted.

Authenticity is also a difficult characteristic to verify on a physical monetary medium. Today's techniques for combating counterfeit currency are increasingly complex, forcing retailers to invest in costly verification systems.

On the other hand, because of their nature, double spending is not a problem for physical currencies. If I give you a €10 bill, it irrevocably leaves my possession and enters yours, which naturally rules out any possibility of multiple spending of the monetary units it embodies. In short, I won't be able to spend this €10 bill again.

For digital currency, the difficulty is different. Ensuring the authenticity and integrity of a coin is often simpler. As we saw in the previous section, Bitcoin's UTXO model makes it possible to trace a coin back to its origin, and thus verify that it was indeed created by a miner in compliance with consensus rules.

On the other hand, ensuring that there is no double-spending is more complex, since all digital goods are in essence information. Unlike physical goods, information is not divided up when it is exchanged, but spreads by multiplying. For example, if I send you a document by e-mail, it will be duplicated. You can't be sure that I've deleted the original document.

Preventing double spending on Bitcoin

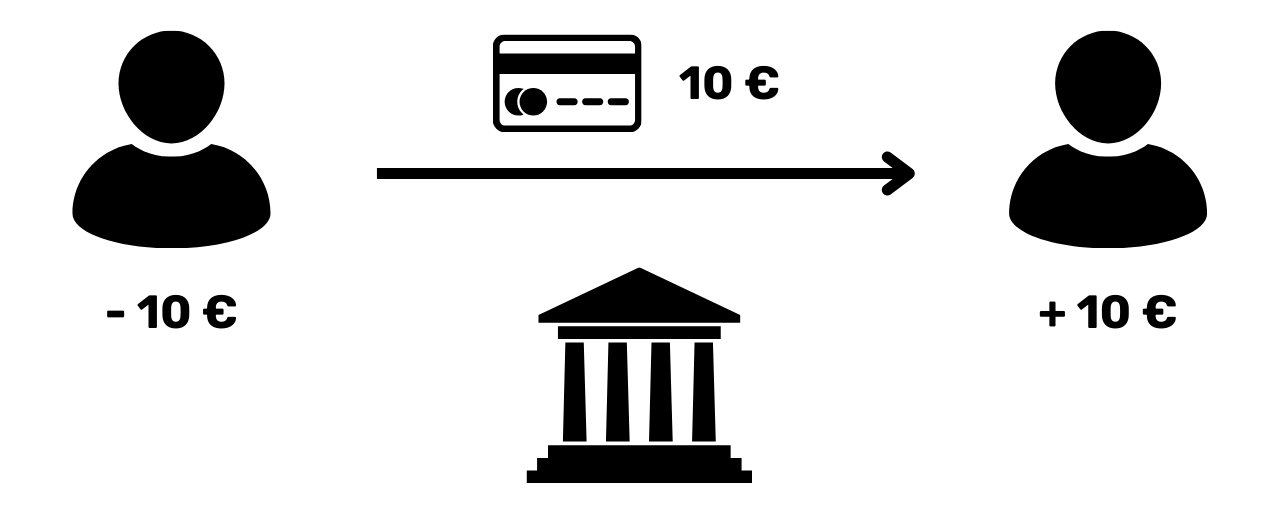

The only way to avoid this duplication of a digital asset is to be aware of all exchanges on the system. In this way, we can know who owns what and update each person's holdings according to the transactions carried out. This is what happens, for example, with scriptural money in the banking system. When you pay €10 to a merchant by credit card, the bank records the exchange and updates the account book.

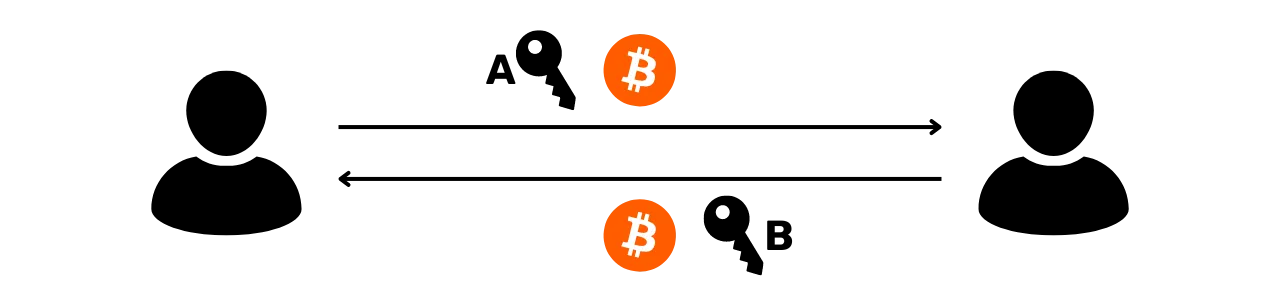

On Bitcoin, double-spending is prevented in the same way. We seek to confirm the absence of a transaction that has already spent the coins in question. If the coins have never been used, then we can be sure that no double spending will occur. This principle was described by Satoshi Nakamoto in the White Paper with the famous phrase:

**The only way to confirm the absence of a transaction is to be aware of all transactions

But unlike the banking model, we don't want to have to trust a central entity on Bitcoin. So all users need to be able to confirm this absence of double spending, without relying on a third party. So everyone needs to be aware of all Bitcoin transactions. This is why Bitcoin transactions are publicly broadcast on all network nodes and recorded in clear text on the blockchain.

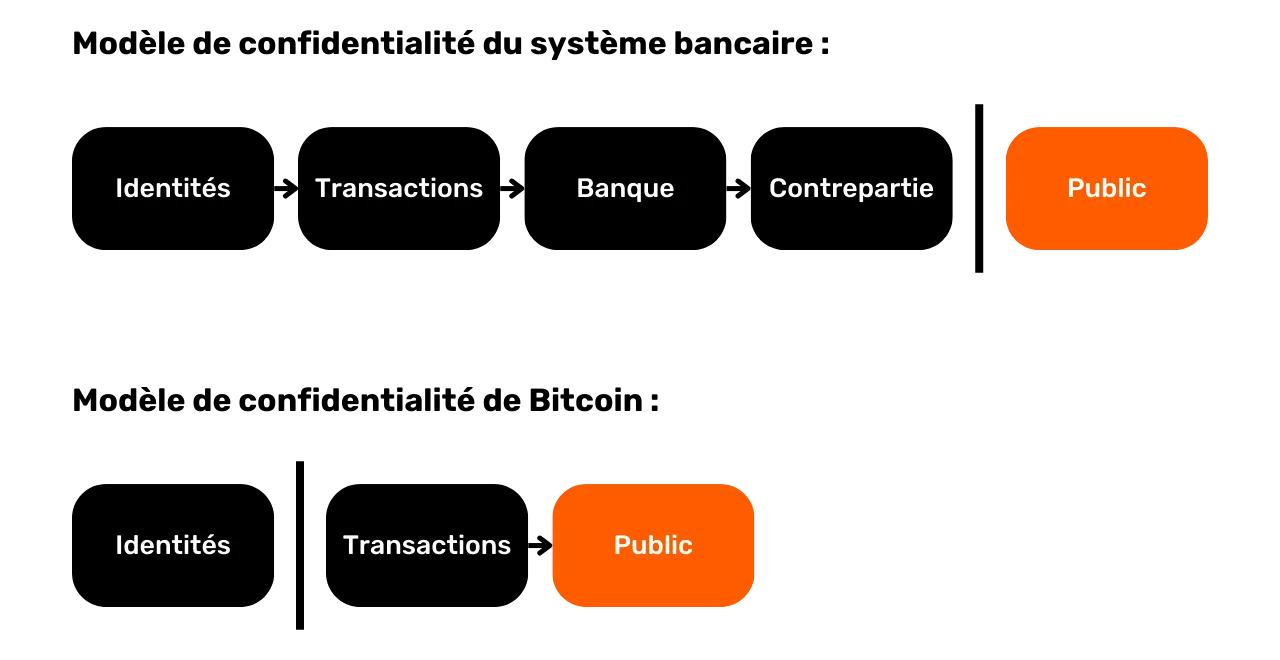

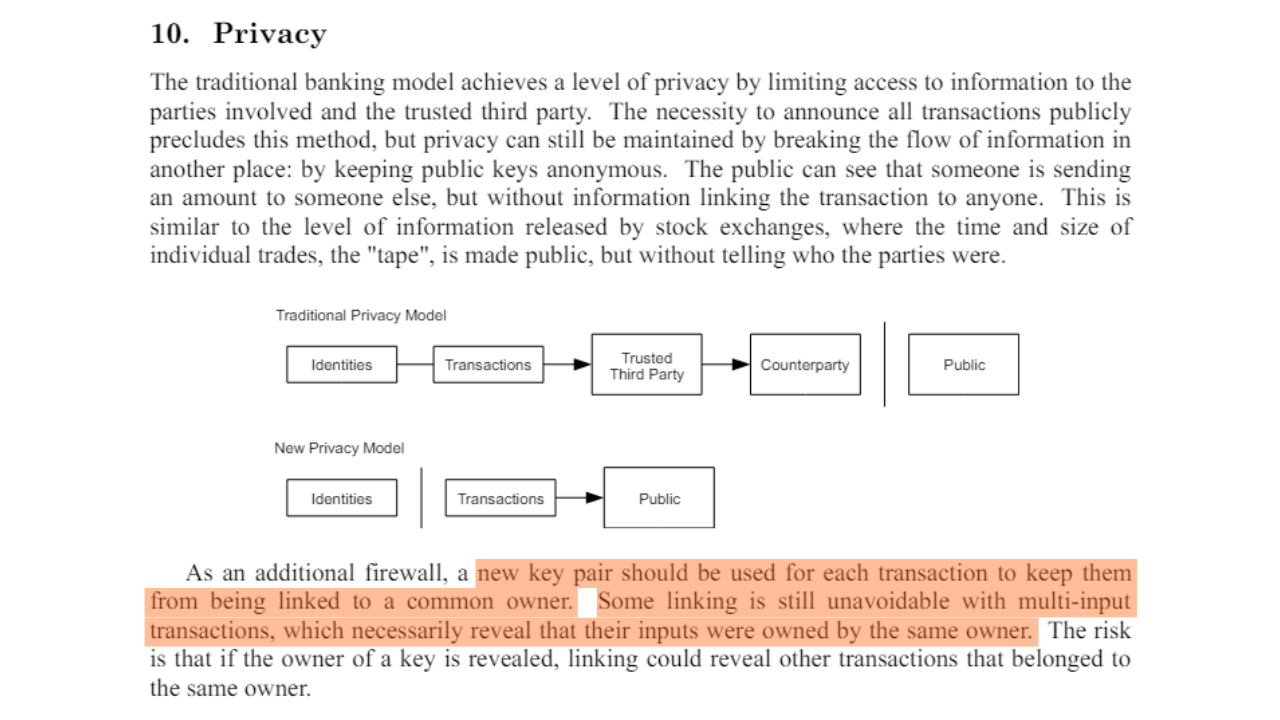

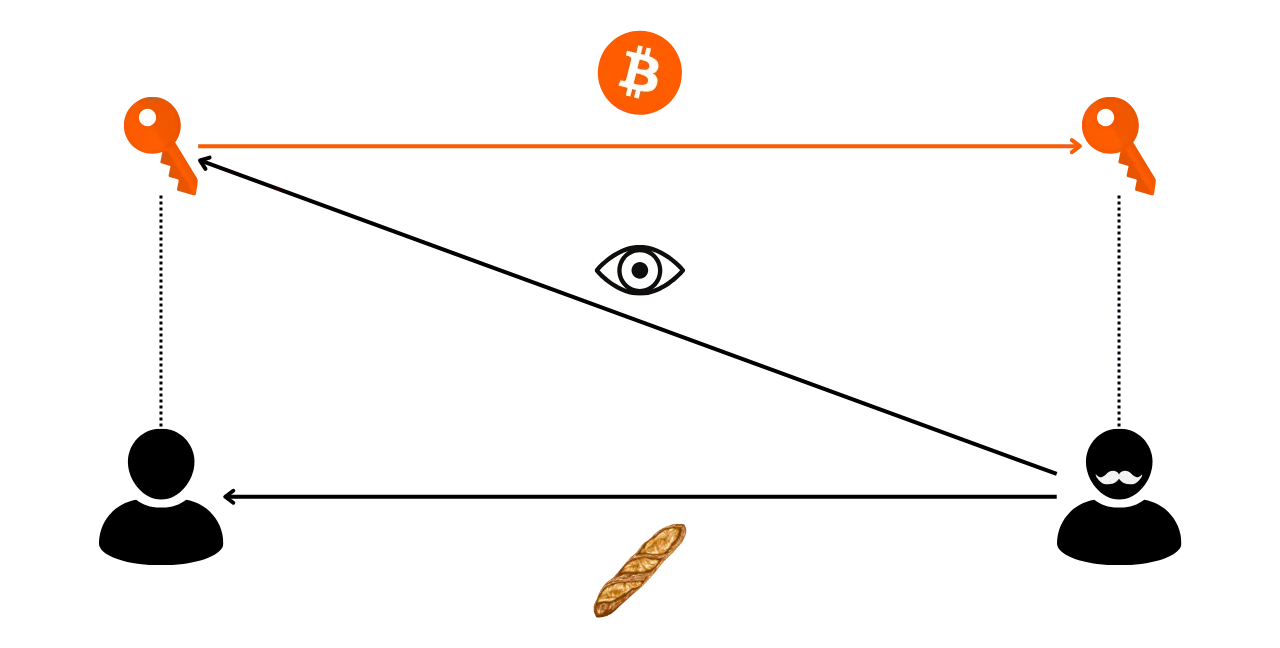

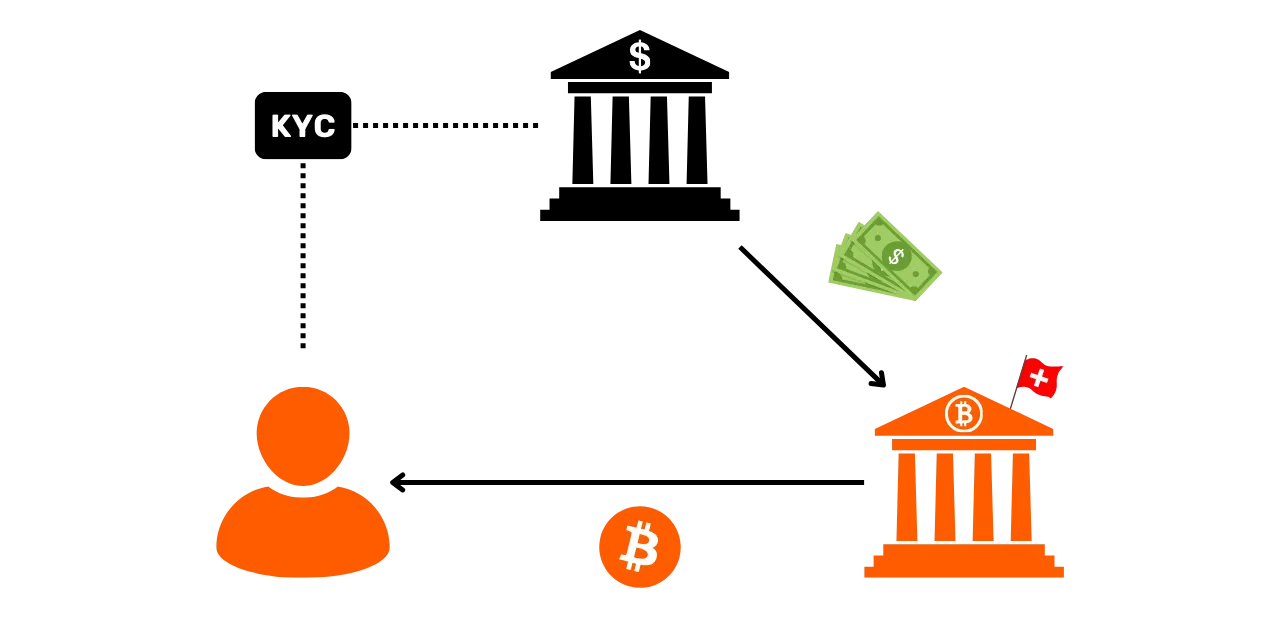

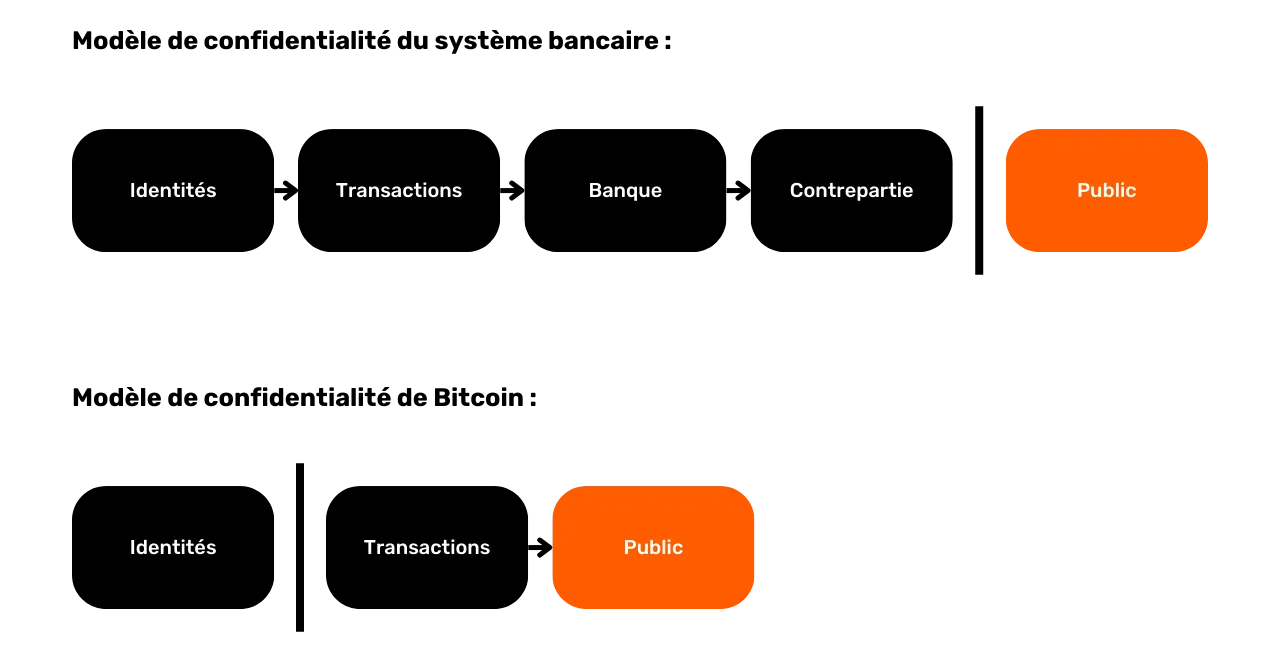

It is precisely this public dissemination of information that complicates the protection of privacy in Bitcoin. In the traditional banking system, in theory, only the financial institution is aware of the transactions carried out. With Bitcoin, on the other hand, all users are informed of all transactions, via their respective nodes.

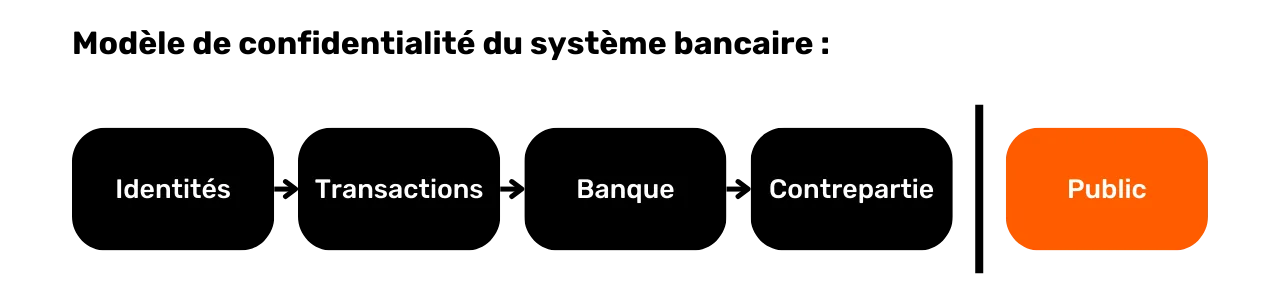

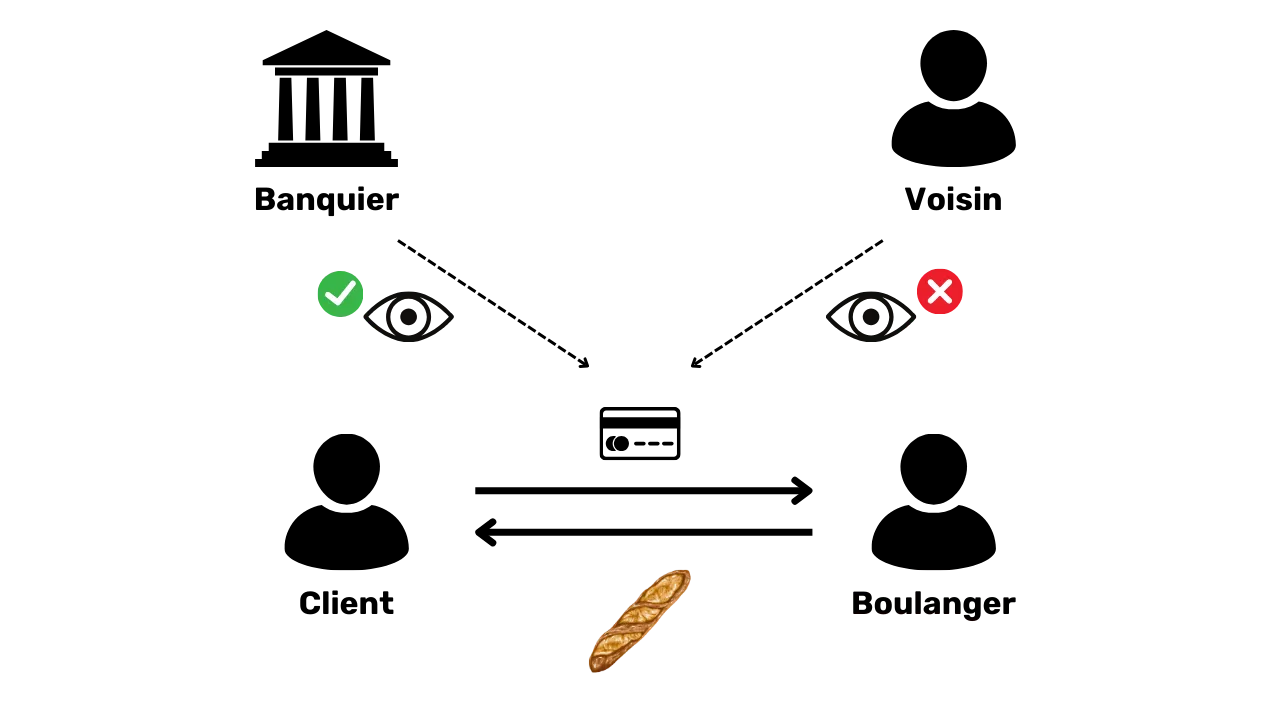

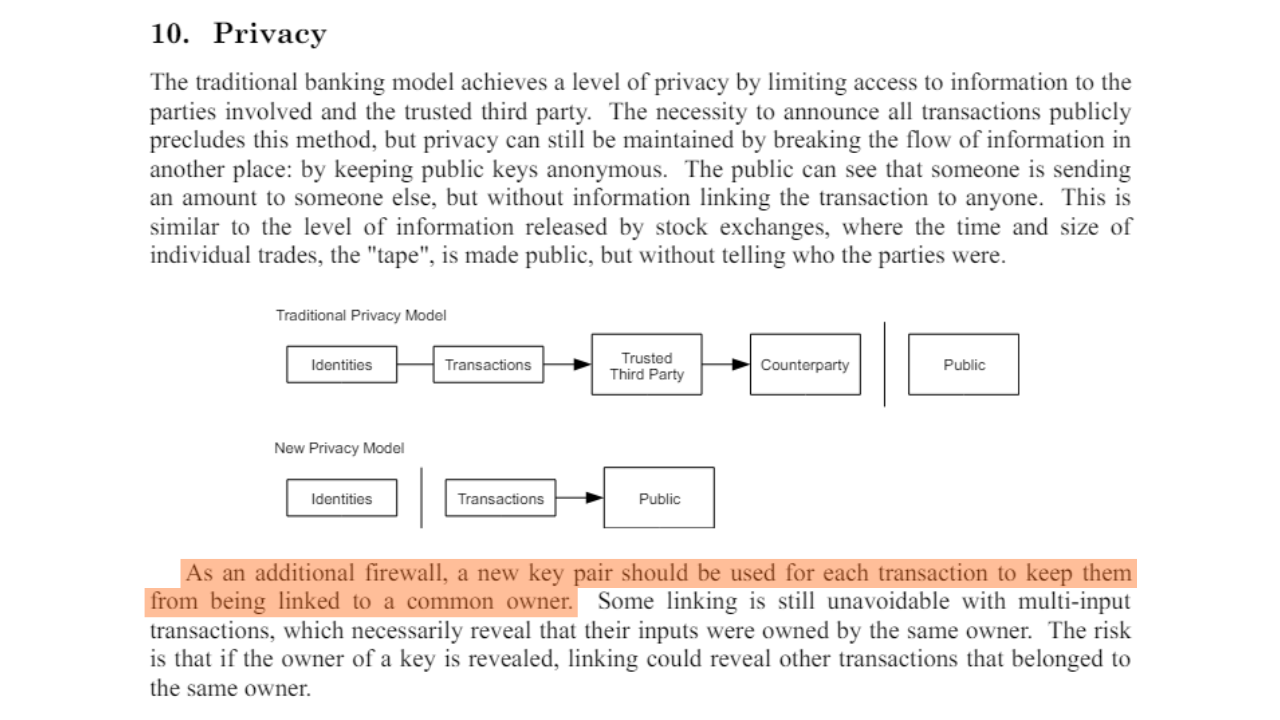

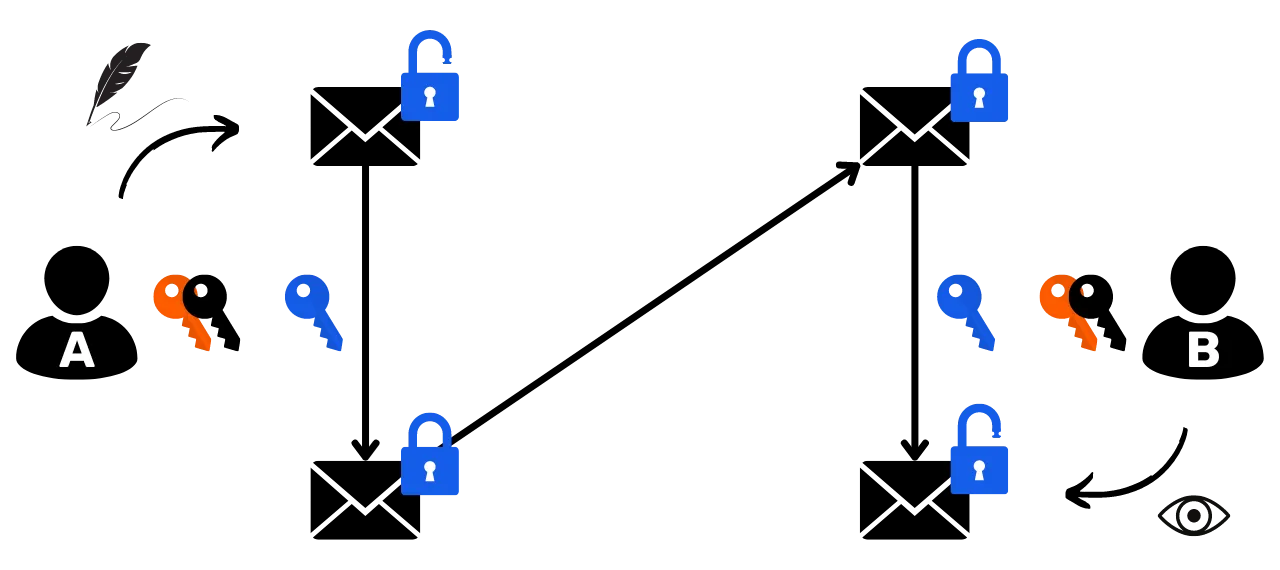

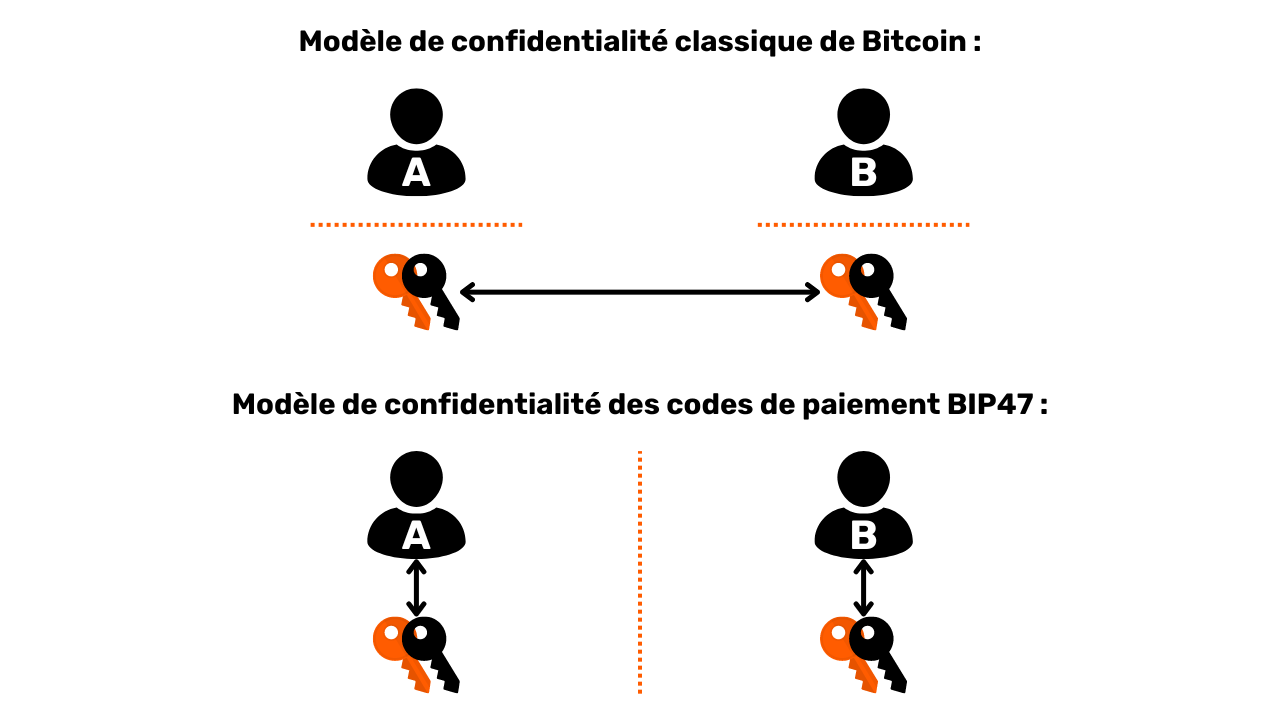

The confidentiality model: banking system vs. Bitcoin

In the traditional system, your bank account is linked to your identity. The banker is able to know which bank account belongs to which customer, and which transactions are associated with it. However, this flow of information is cut off between the bank and the public domain. In other words, it is impossible to know the balance and transactions of a bank account belonging to another individual. Only the bank has access to this information.

For example, your banker knows that you buy your baguette every morning from the local baker, but your neighbor has no knowledge of this transaction. In this way, the flow of information is accessible to the parties concerned, notably the bank, but remains inaccessible to outsiders.

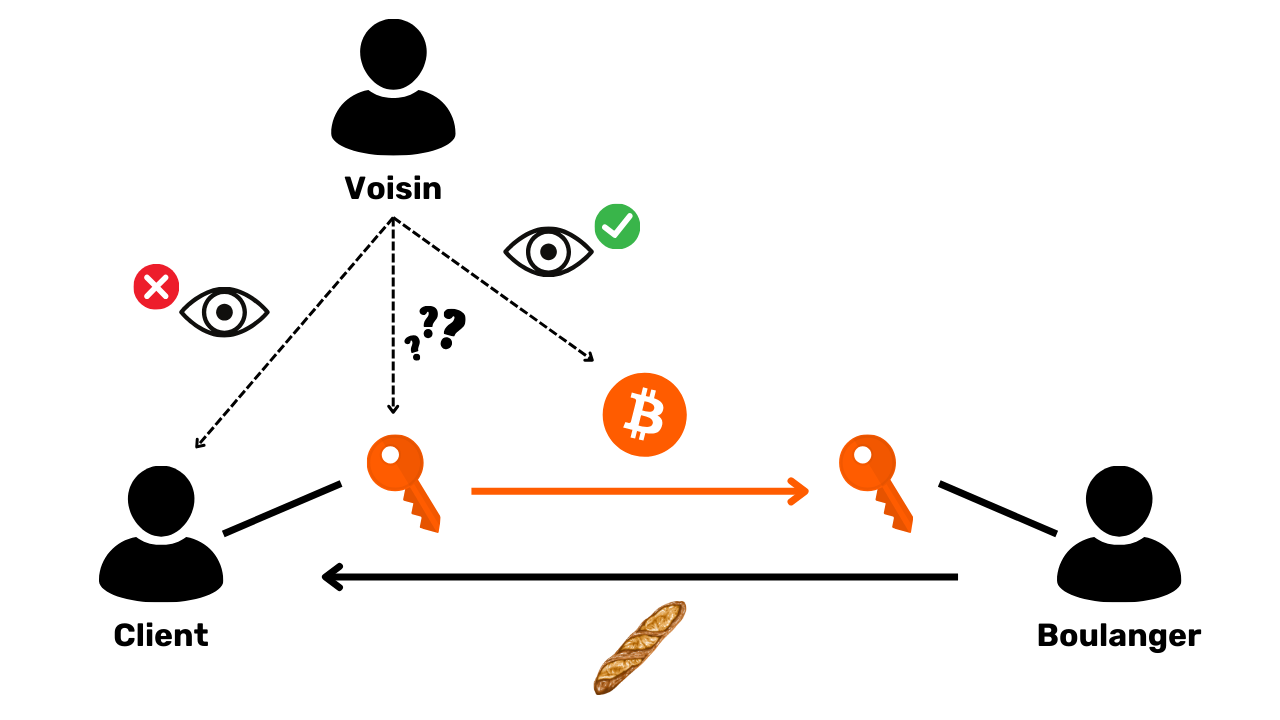

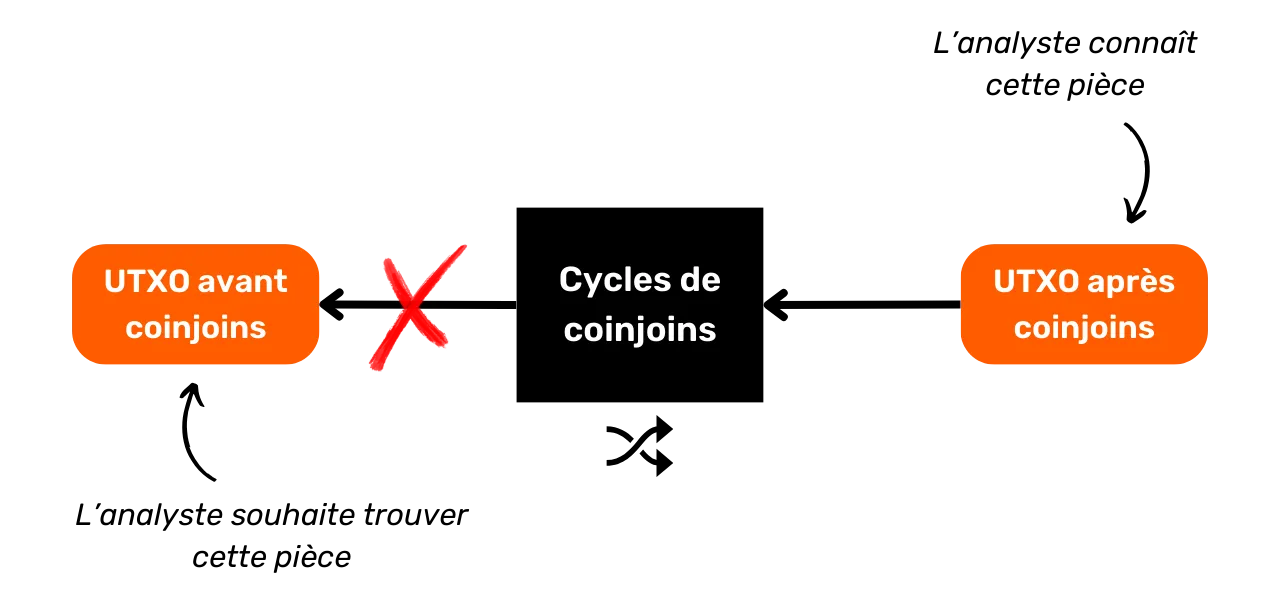

Because of the constraint of public dissemination of transactions that we saw in the previous section, Bitcoin's confidentiality model cannot follow the model of the banking system. In Bitcoin's case, since the flow of information cannot be broken between the transactions and the public domain, the privacy model relies on the separation between the user's identity and the transactions themselves.

For example, if you buy a baguette from the baker, paying in BTC, your neighbor, who has his own complete node, can see your transaction go through, just as he can see all the other transactions in the system. However, if confidentiality principles are respected, he should not be able to link this specific transaction to your identity.

But since Bitcoin transactions are made public, it is still possible to establish links between them to deduce information about the parties involved. This activity even constitutes a specialty in its own right, known as "blockchain analysis". In the next part of the course, I invite you to explore the fundamentals of blockchain analysis, so that you can understand how your bitcoins are traced and better defend yourself against them.

Understanding and protecting against chain analysis

What is Bitcoin chain analysis?

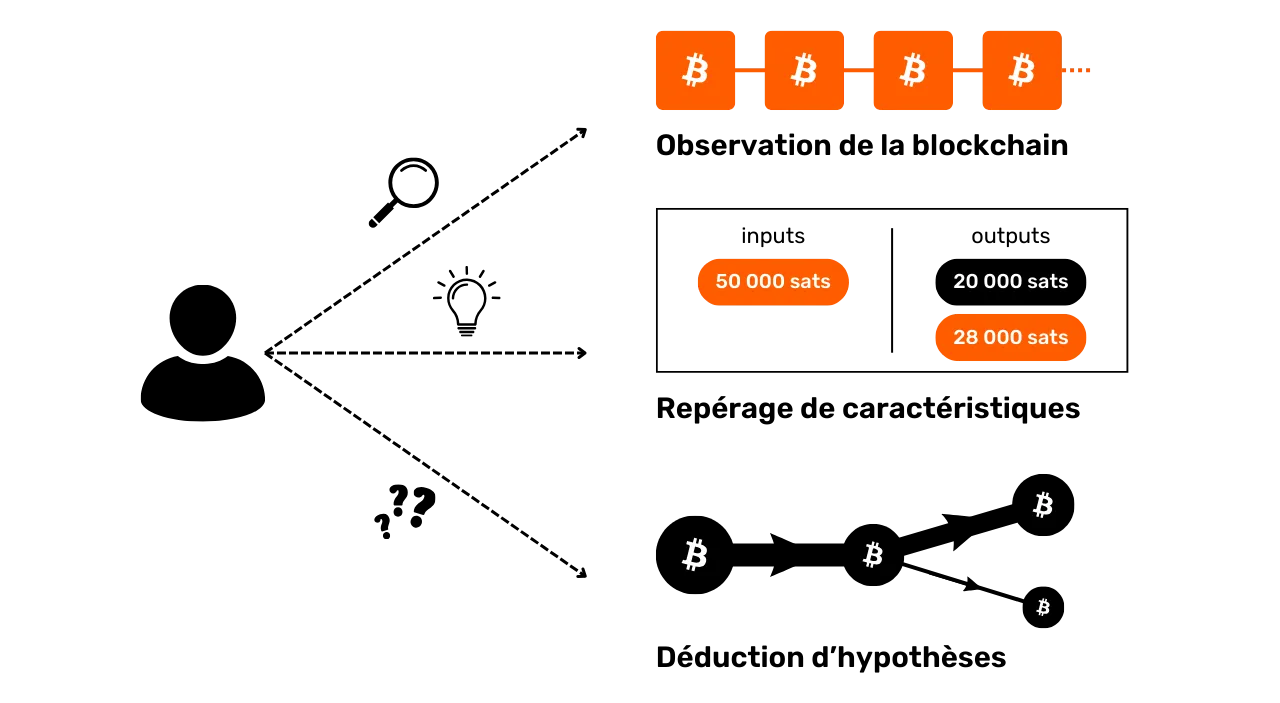

Definition and operation

Blockchain analysis is the practice of tracing the flow of bitcoins on the blockchain. Generally speaking, chain analysis is based on the observation of characteristics in samples of previous transactions. It then consists of identifying these same characteristics on a transaction that we wish to analyze, and deducing plausible interpretations from them. This problem-solving method, based on a practical approach to finding a good enough solution, is known as a "heuristic".

In layman's terms, there are three main stages in chain analysis:

Observing the blockchain ;

The identification of known features ;

**The deduction of assumptions **

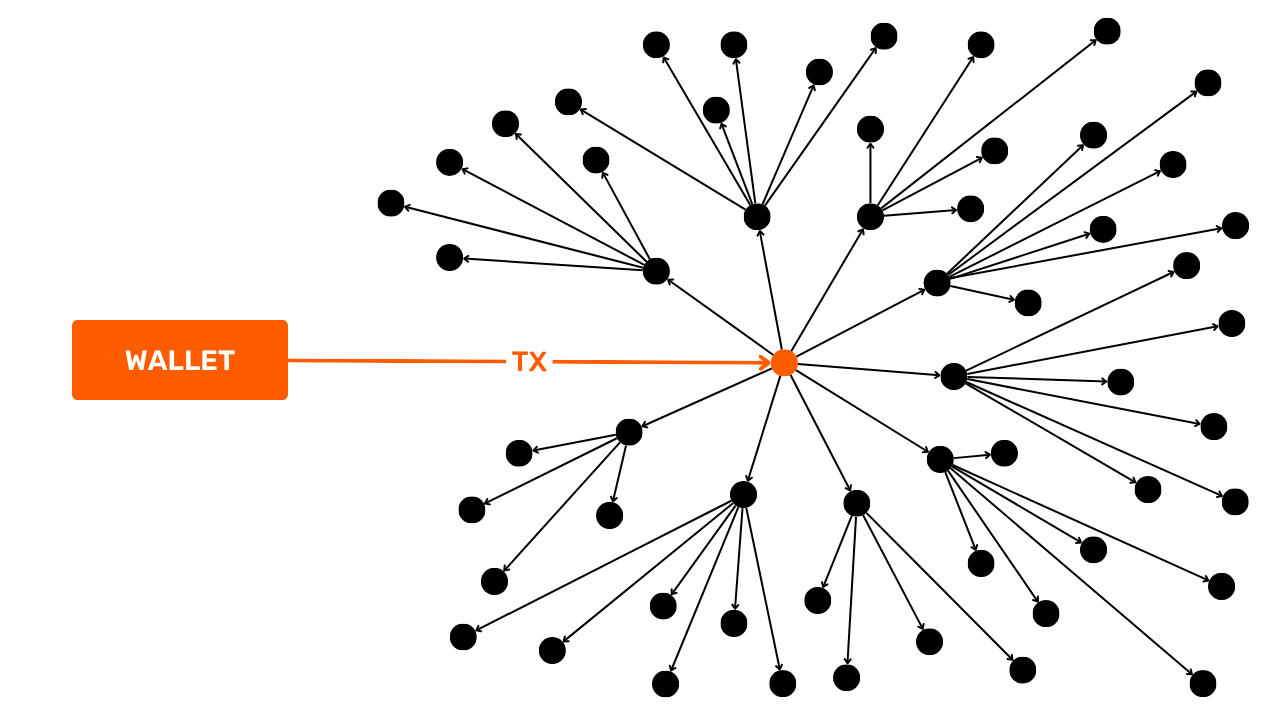

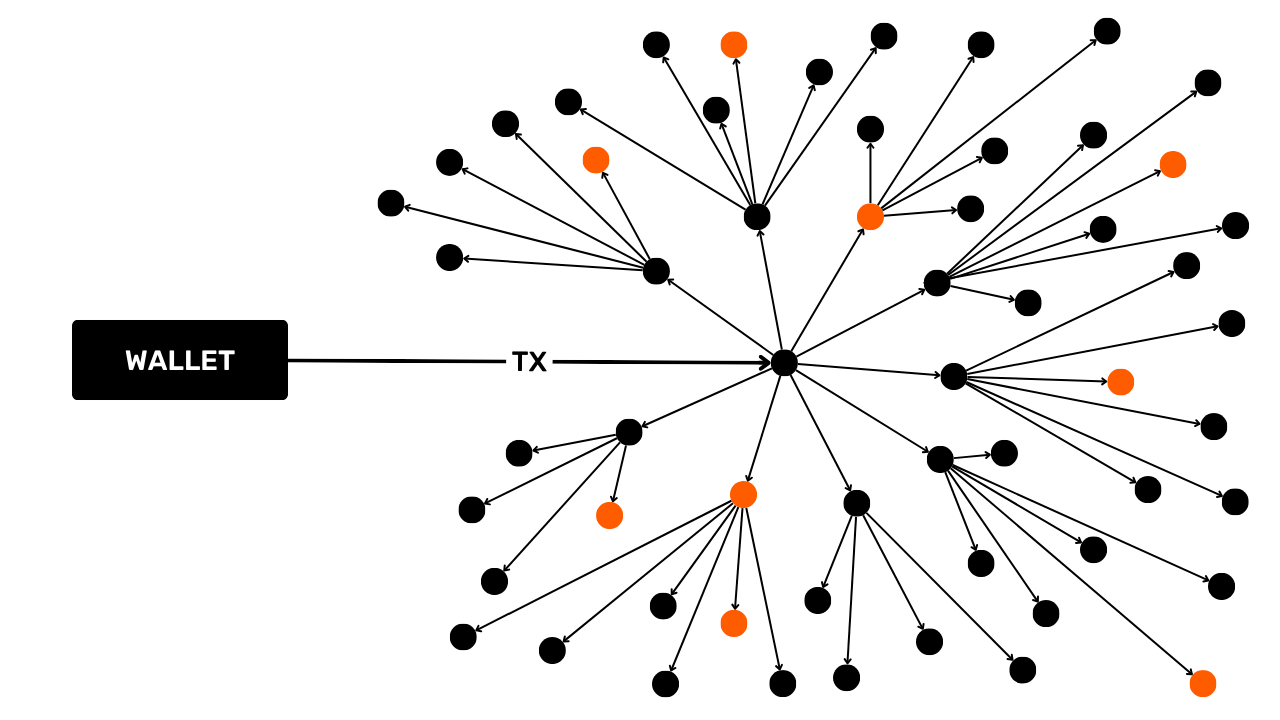

Blockchain analysis can be performed by anyone. All you need is access to the blockchain's public information via a complete node to observe transaction movements and make hypotheses. There are also free tools that facilitate this analysis, such as OXT.me, which we'll explore in detail in the last two chapters of this section. However, the main risk to confidentiality comes from companies specializing in string analysis. These companies have taken blockchain analysis to an industrial scale and sell their services to financial institutions and governments. Among these companies, Chainalysis is surely the best known.

Chain analysis objectives

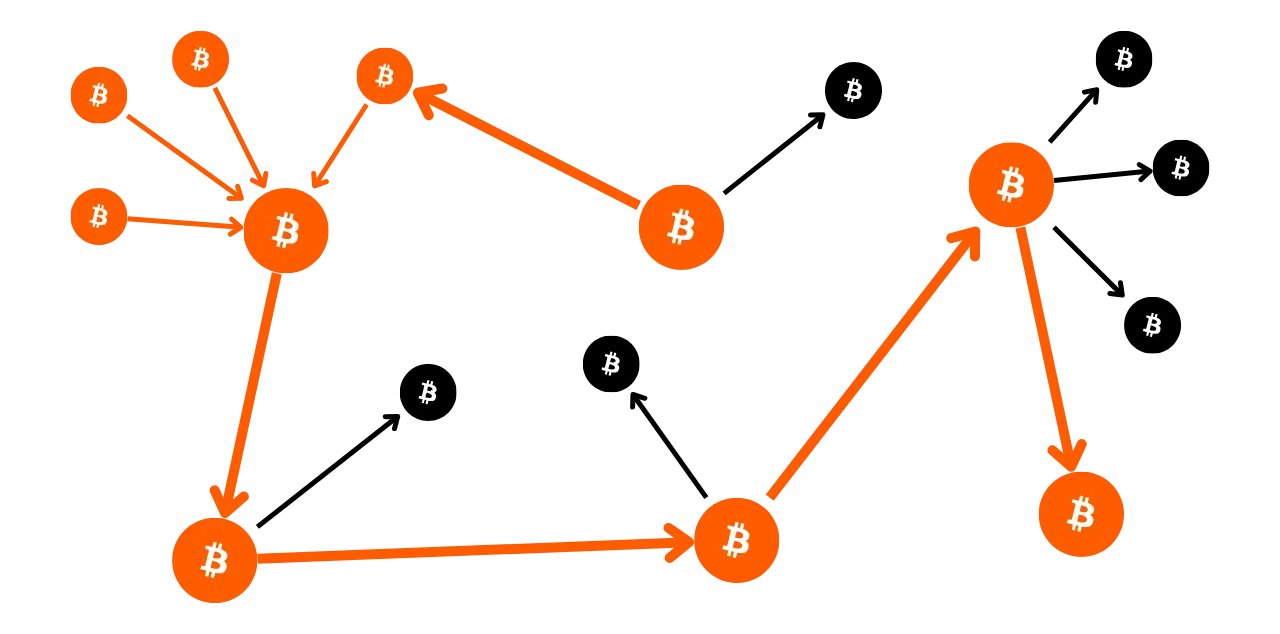

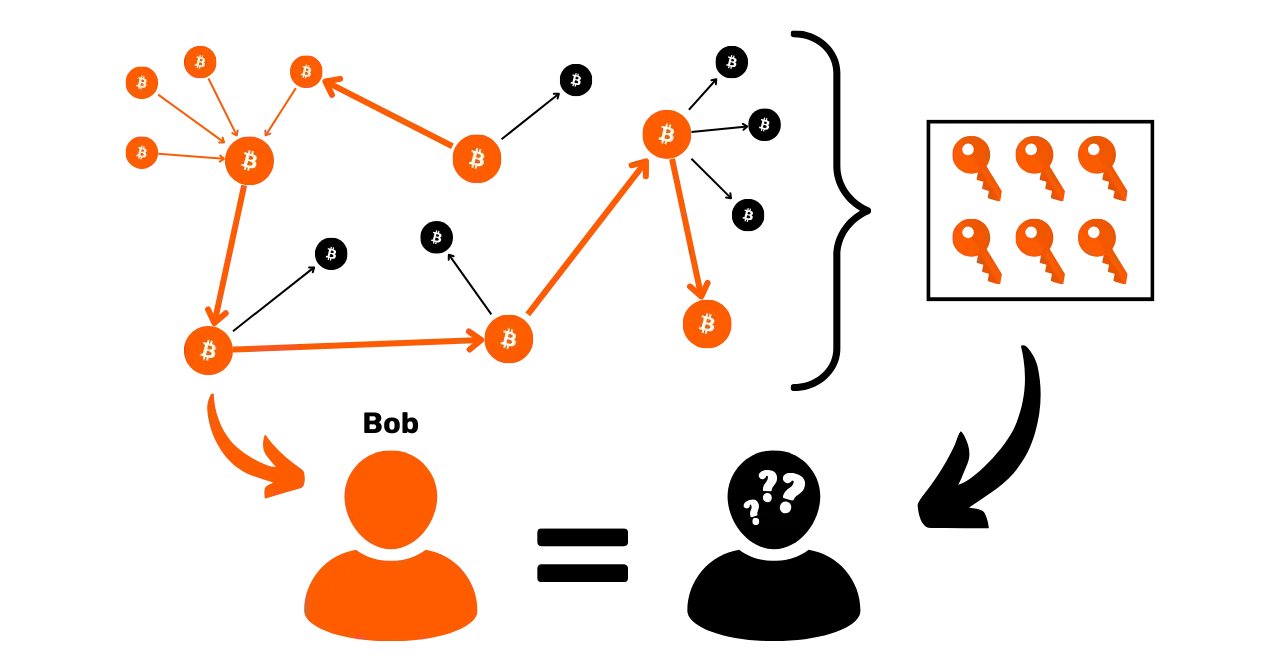

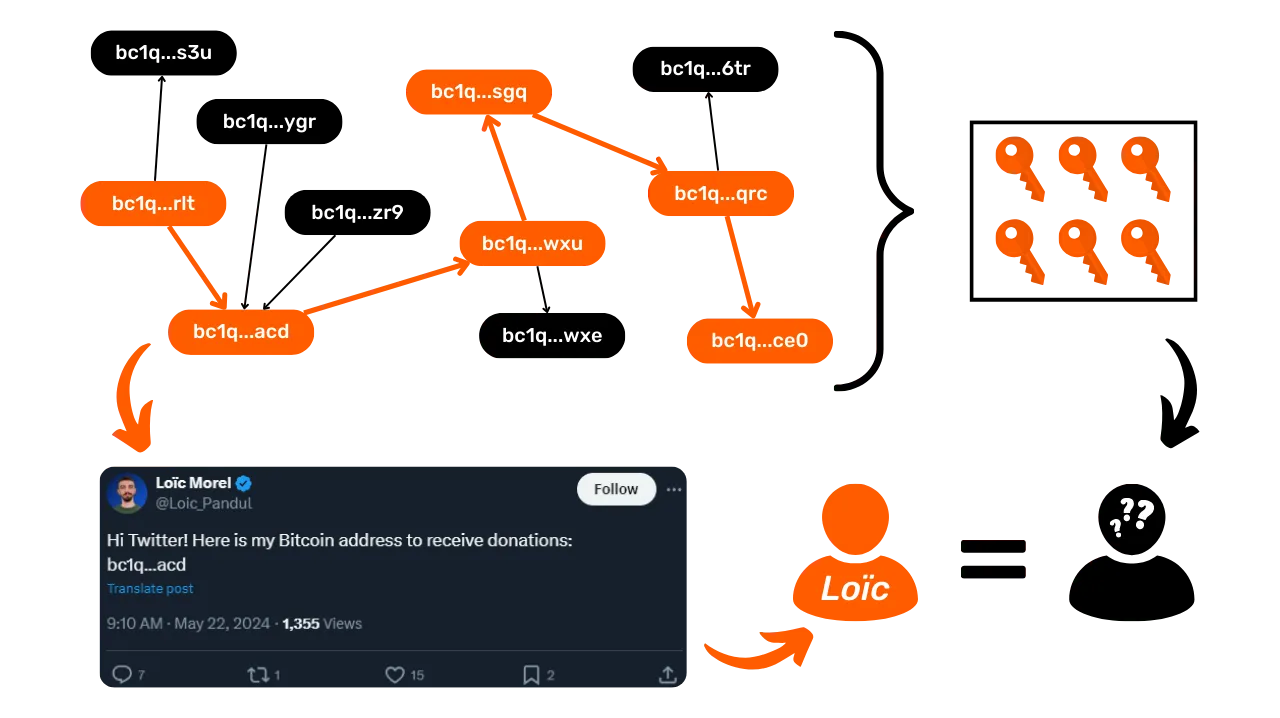

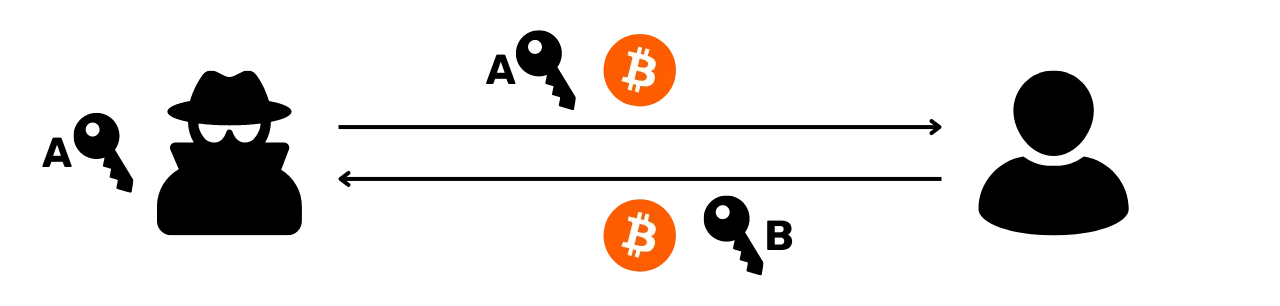

One of the aims of blockchain analysis is to group together various activities on Bitcoin in order to determine the uniqueness of the user who carried them out. Subsequently, it will be possible to attempt to link this cluster of activities to a real identity.

Think back to the previous chapter. I explained why Bitcoin's privacy model was originally based on the separation of user identity from transactions. It would therefore be tempting to think that blockchain analysis is useless, since even if we manage to aggregate onchain activities, we can't associate them with a real identity.

Theoretically, this statement is correct. In the first part of this course, we saw that cryptographic key pairs are used to establish conditions on UTXO. In essence, these key pairs divulge no information about the identity of their holders. So, even if we manage to group together the activities associated with different key pairs, this tells us nothing about the entity behind these activities.

However, the practical reality is far more complex. There are a multitude of behaviors that can link a real identity to onchain activity. In analysis, this is called an entry point, and there are a multitude of them.

The most common is KYC (Know Your Customer). If you withdraw your Bitcoins from a regulated platform to one of your personal receiving addresses, then some people are able to link your identity to that address. More broadly, an entry point can be any form of interaction between your real life and a Bitcoin transaction. For example, if you publish a receiving address on your social networks, this could be an entry point for analysis. If you make a payment in Bitcoins to your baker, he will be able to associate your face (part of your identity) with a Bitcoin address.

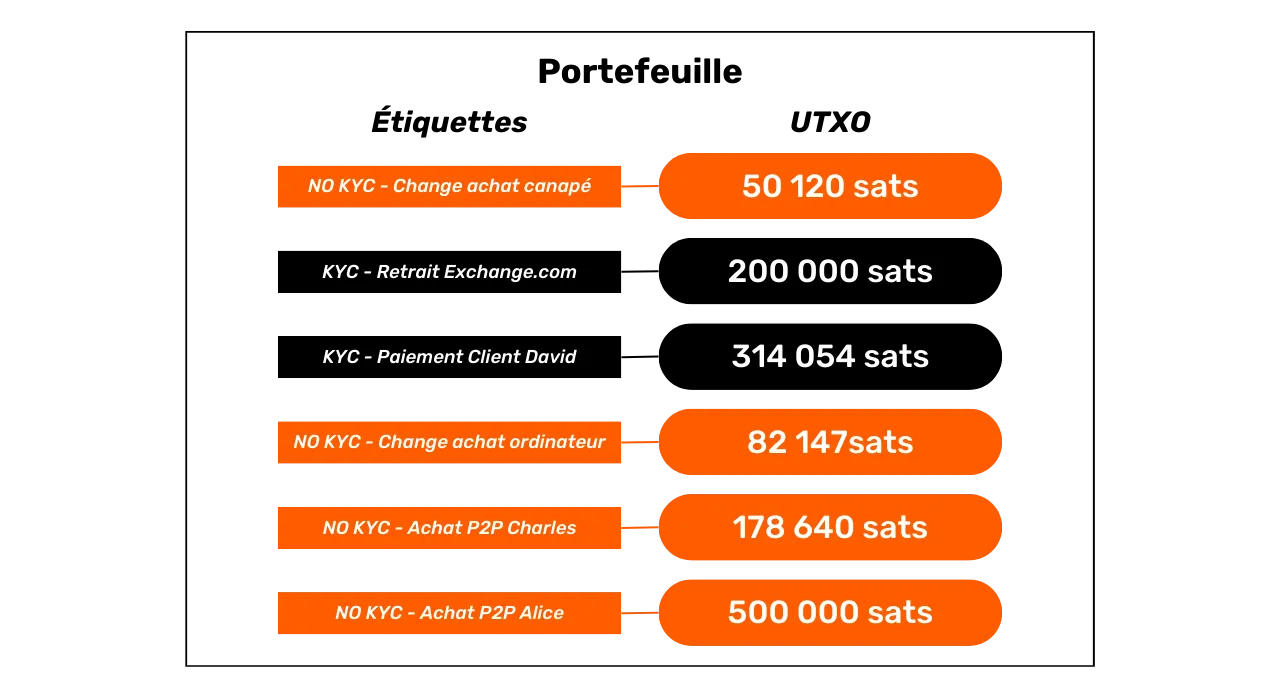

These entry points are virtually unavoidable when using Bitcoin. Although we may seek to restrict their scope, they will always be present. That's why it's crucial to combine methods aimed at preserving your privacy. While maintaining a separation between your real identity and your transactions is an interesting approach, it remains insufficient today. Indeed, if all your onchain activities can be grouped together, then even the smallest entry point is likely to compromise the single layer of confidentiality you've established.

Defending yourself against chain analysis

So we also need to be able to cope with blockchain analysis in our use of Bitcoin. By doing so, we can minimize the aggregation of our activities and limit the impact of an entry point on our privacy.

What better way to counter blockchain analysis than to learn about the methods used in it? If you want to know how to improve your privacy on Bitcoin, you need to understand these methods. This will give you a better grasp of techniques such as coinjoin or payjoin (techniques we'll look at in the final parts of the course), and reduce the mistakes you might make.

https://planb.network/tutorials/privacy/on-chain/payjoin-848b6a23-deb2-4c5f-a27e-93e2f842140f

In this, we can draw an analogy with cryptography and cryptanalysis. A good cryptographer is first and foremost a good cryptanalyst. To devise a new encryption algorithm, you need to know what attacks it will face, and also study why previous algorithms have been broken. The same principle applies to Bitcoin privacy. Understanding blockchain analysis methods is the key to protecting against them. That's why I've included a whole section on chain analysis in this training course.

Chain analysis methods

It's important to understand that string analysis is not an exact science. It relies on heuristics derived from previous observations or logical interpretations. These rules allow us to obtain fairly reliable results, but never with absolute precision. In other words, chain analysis always involves a dimension of probability in the conclusions reached. For example, it may be possible to estimate with varying degrees of certainty that two addresses belong to the same entity, but total certainty will always be out of reach.

The whole point of chain analysis lies precisely in the aggregation of various heuristics to minimize the risk of error. In a way, it's an accumulation of evidence that brings us closer to reality.

These famous heuristics can be grouped into different categories, which we will describe in detail below:

- Transaction patterns ;**

- Transaction-internal heuristics ;**

- Heuristics external to the transaction.**

Satoshi Nakamoto and chain analysis

The first two chain analysis heuristics were discovered by Satoshi Nakamoto himself. He talks about them in Part 10 of Bitcoin's White Paper. They are :

- cIOH (Common Input Ownership Heuristic);

- and address reuse.

Source: S. Nakamoto, "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System", https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf, 2009.

We'll see what they are in the following chapters, but it's already interesting to note that these two heuristics still retain a pre-eminence in chain analysis today.

Transaction patterns

A transaction pattern is simply an overall model or structure of a typical transaction, which can be found on the blockchain, and whose likely interpretation is known. When studying patterns, we focus on a single transaction and analyze it at a high level.

In other words, we're only going to look at the number of UTXO in inputs and the number of UTXO in outputs, without dwelling on the more specific details or environment of the transaction. Based on the observed pattern, we can interpret the nature of the transaction. We will then look for characteristics of its structure and deduce an interpretation.

In this section, we'll look together at the main transaction models encountered in chain analysis, and for each model, I'll give you the likely interpretation of this structure, as well as a concrete example.

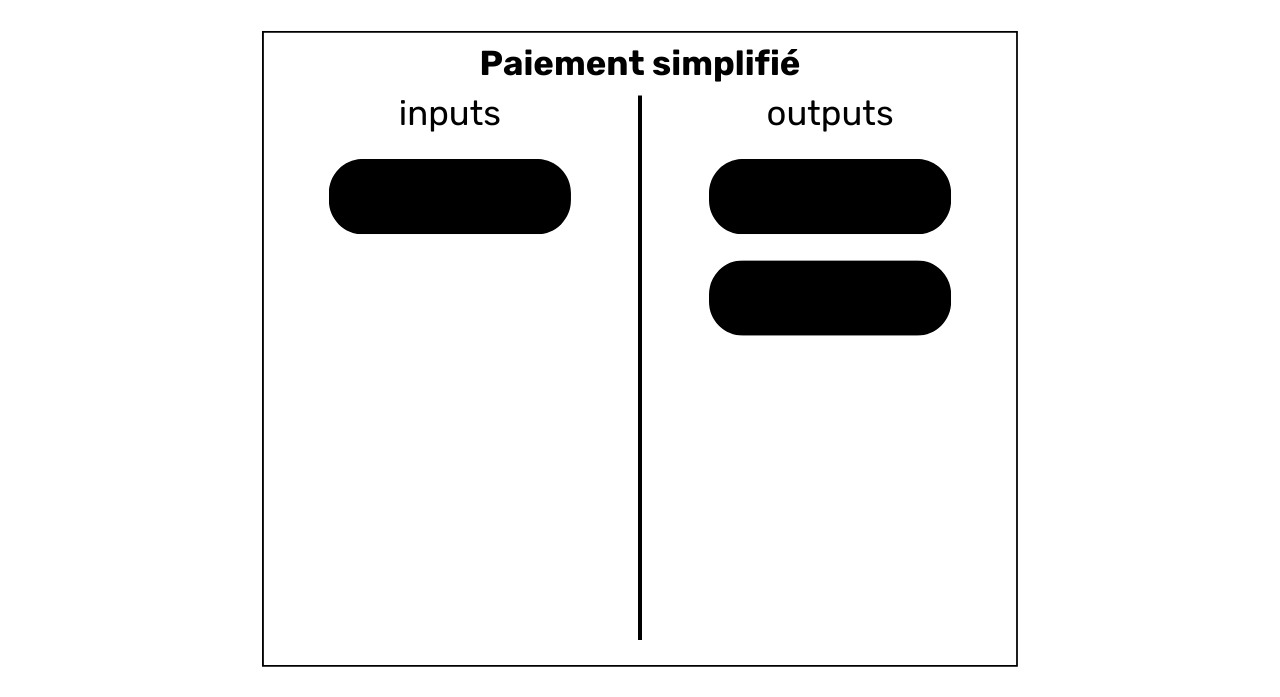

Single shipment (or single payment)

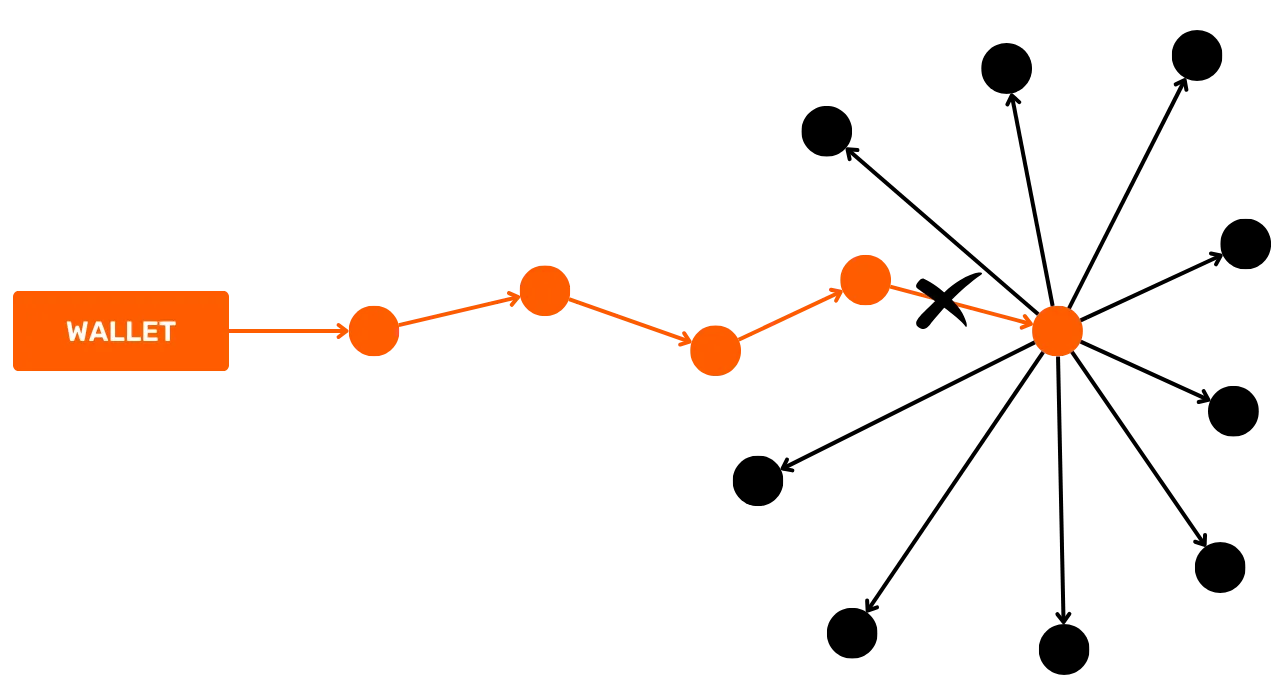

Let's start with a very common pattern, since it's the one that emerges on most bitcoin payments. The simple payment model is characterized by the consumption of one or more UTXOs as inputs and the production of 2 UTXOs as outputs. This model therefore looks like this:

When we spot this transaction structure on the blockchain, we can already draw an interpretation. As its name suggests, this model indicates that we are in the presence of a sending or payment transaction. The user has consumed his own UTXO in inputs to satisfy in outputs a payment UTXO and an exchange UTXO (money returned to the same user).

We therefore know that the observed user is probably no longer in possession of one of the two output UTXOs (the payment UTXO), but is still in possession of the other UTXO (the exchange UTXO).

For the moment, we can't specify which output represents which UTXO, as this is not the purpose of the pattern study. We'll get there by relying on the heuristics we'll study in the following sections. At this stage, our objective is limited to identifying the nature of the transaction in question, which in this case is a simple send.

For example, here is a Bitcoin transaction that adopts the simple send pattern:

b6cc79f45fd2d7669ff94db5cb14c45f1f879ea0ba4c6e3d16ad53a18c34b769

Source : Mempool.space

After this first example, you should have a better understanding of what it means to study a "transaction model". We examine a transaction by focusing solely on its structure, without taking into account its environment or the specific details of the transaction. In this first step, we're only looking at the big picture.

Now that you understand what a pattern is, let's move on to the other existing models.

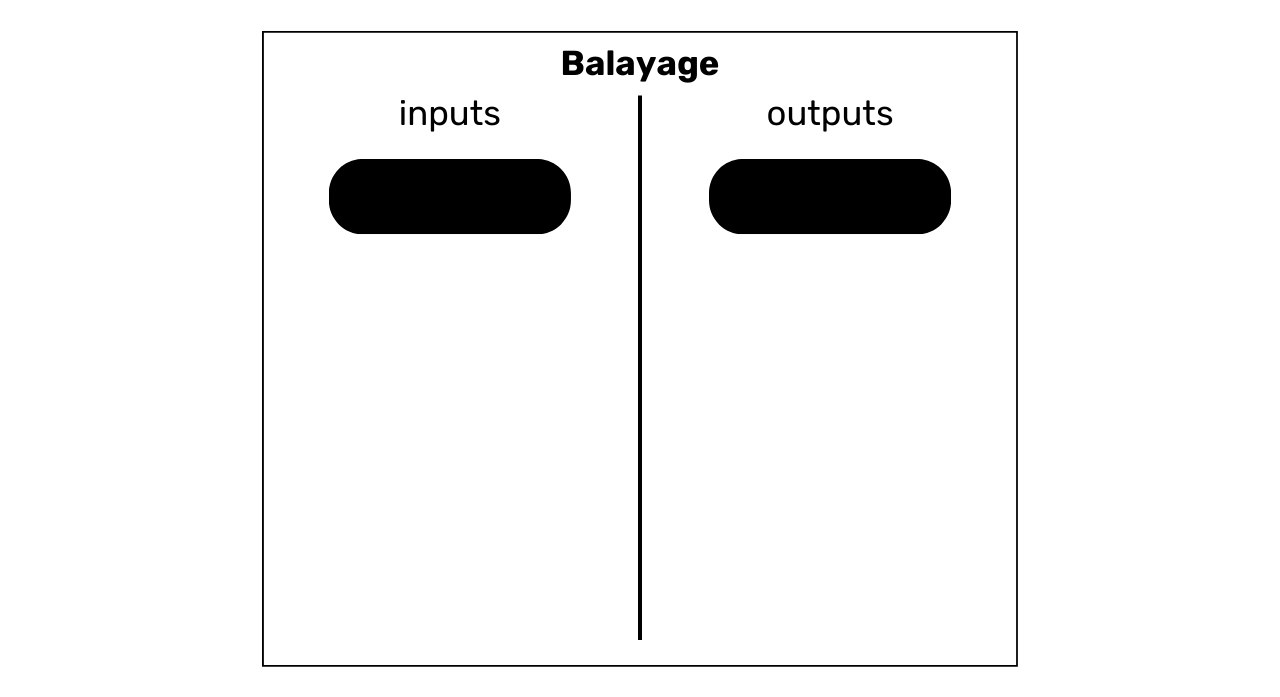

Sweeping

This second model is characterized by the consumption of a single UTXO as input and the production of a single UTXO as output.

The interpretation of this model is that we are in the presence of a self-transfer. The user has transferred his bitcoins to himself, to another address belonging to him. Since there is no exchange on the transaction, it's highly unlikely that we're in the presence of a payment. Indeed, when a payment is made, it is almost impossible for the payer to have a UTXO corresponding exactly to the amount required by the seller, plus the transaction fee. In general, the payer is therefore obliged to produce an exchange output.

We then know that the observed user is probably still in possession of this UTXO. In the context of a chain analysis, if we know that the UTXO used as input to the transaction belongs to Alice, we can assume that the UTXO used as output also belongs to her. What will become interesting later on is to find transaction-internal heuristics that could reinforce this assumption (we'll look at these heuristics in chapter 3.3).

For example, here is a Bitcoin transaction that adopts the sweep pattern:

35f1072a0fda5ae106efb4fda871ab40e1f8023c6c47f396441ad4b995ea693d

Source : Mempool.space

Beware, however, that this type of pattern can also reveal a self-transfer to the account of a cryptocurrency exchange platform. It will be the study of known addresses and the context of the transaction that will tell us whether it's a swipe to a self-custody wallet or a withdrawal to a platform. Indeed, the addresses of exchange platforms are often easily identifiable.

Let's take Alice's example again: if the scan leads to an address known to a platform (such as Binance, for example), this may mean that the bitcoins have been transferred out of Alice's direct possession, probably with the intention of selling them or storing them on this platform. On the other hand, if the destination address is unknown, it's reasonable to assume that it's simply another wallet still belonging to Alice. But this type of study is more in the category of heuristics than patterns.

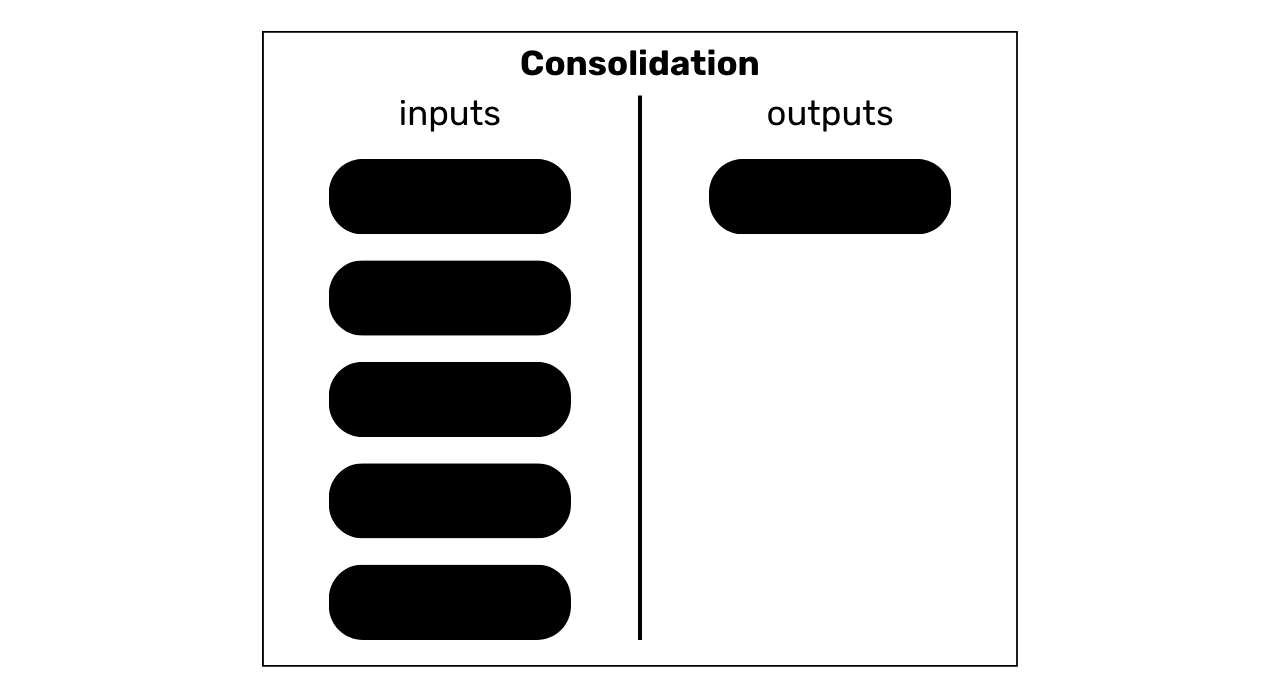

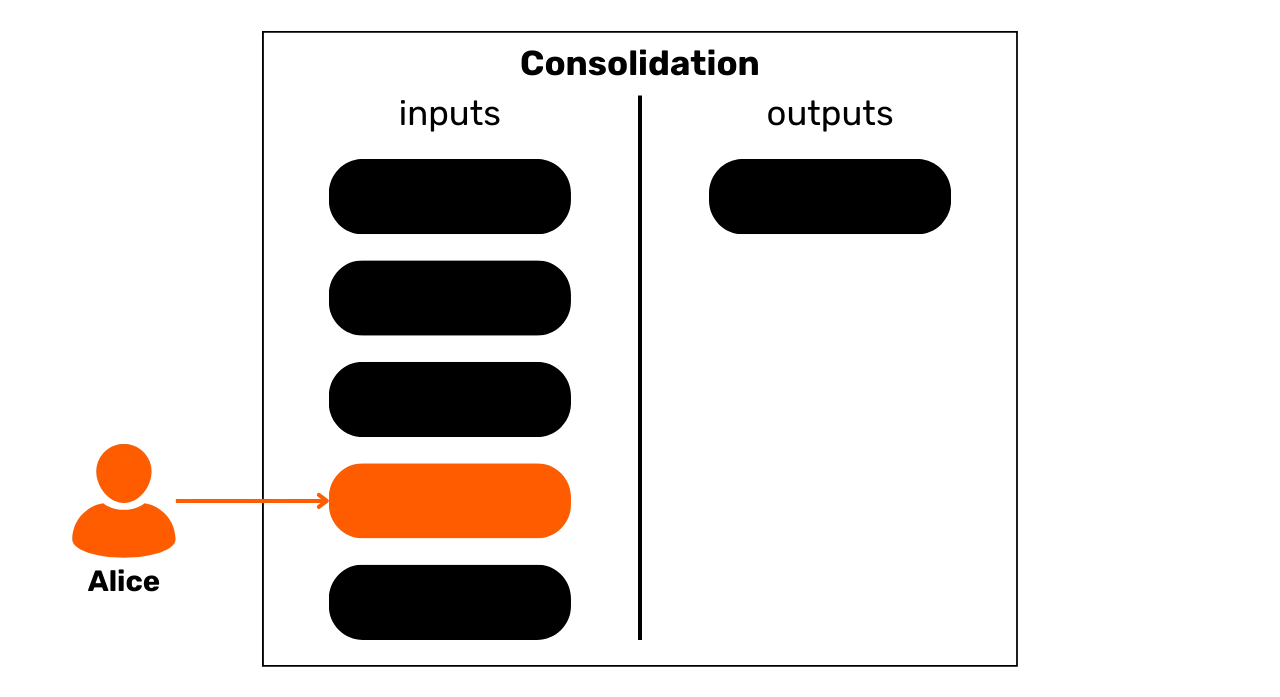

Consolidation

This model is characterized by the consumption of several UTXOs at the input and the production of a single UTXO at the output.

The interpretation of this pattern is that we are in the presence of consolidation. This is a common practice among Bitcoin users, aimed at merging several UTXOs in anticipation of a possible increase in transaction fees. By performing this operation during a period when fees are low, it is possible to save on future fees. We'll talk more about this practice in chapter 4.3.

We can deduce that the user behind this transaction model was probably in possession of all the UTXOs in input and is still in possession of the UTXO in output. So it's probably an auto-transfer.

Like the sweep, this type of pattern can also reveal a self-transfer to the account of an exchange platform. It will be the study of known addresses and the context of the transaction that will tell us whether it's a consolidation to a self-custody portfolio or a withdrawal to a platform.

For example, here is a Bitcoin transaction that adopts the consolidation pattern:

77c16914211e237a9bd51a7ce0b1a7368631caed515fe51b081d220590589e94

Source : Mempool.space

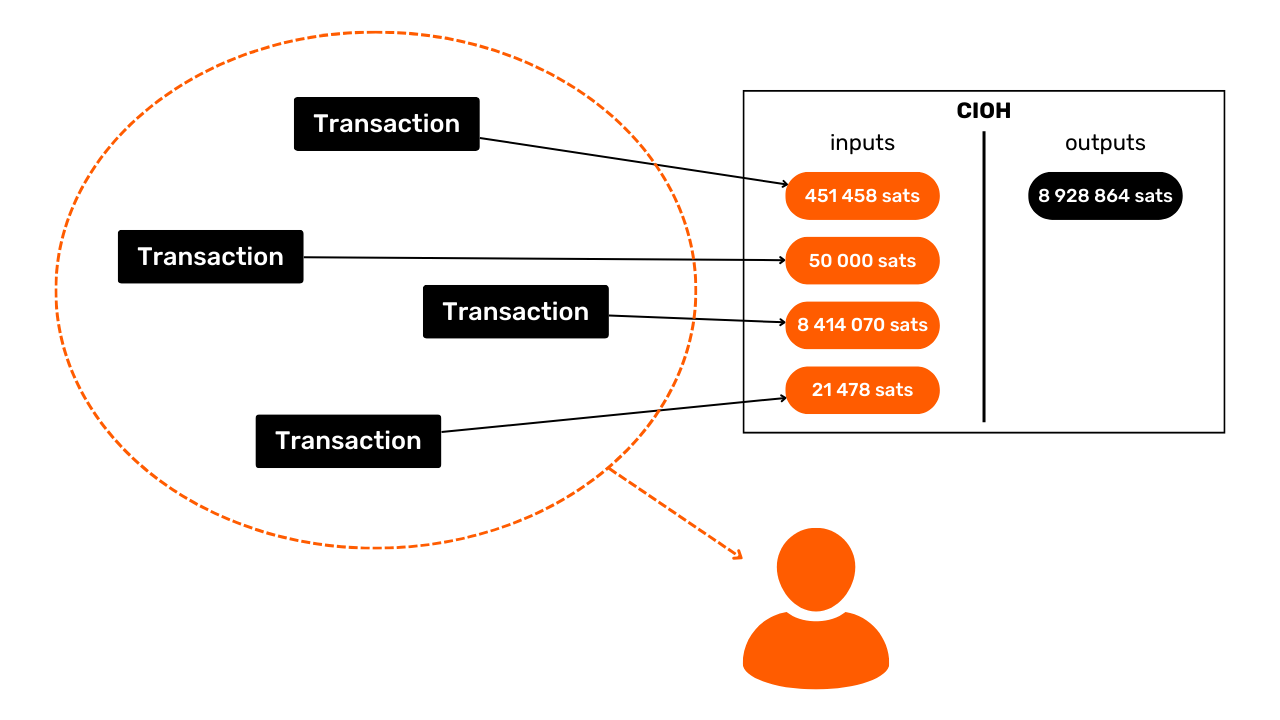

In a chain analysis, this model can reveal a great deal of information. For example, if we know that one of the inputs belongs to Alice, we can assume that all the other inputs and the output of this transaction also belong to her. This assumption would then make it possible to go back up the chain of previous transactions to discover and analyze other transactions likely to be associated with Alice.

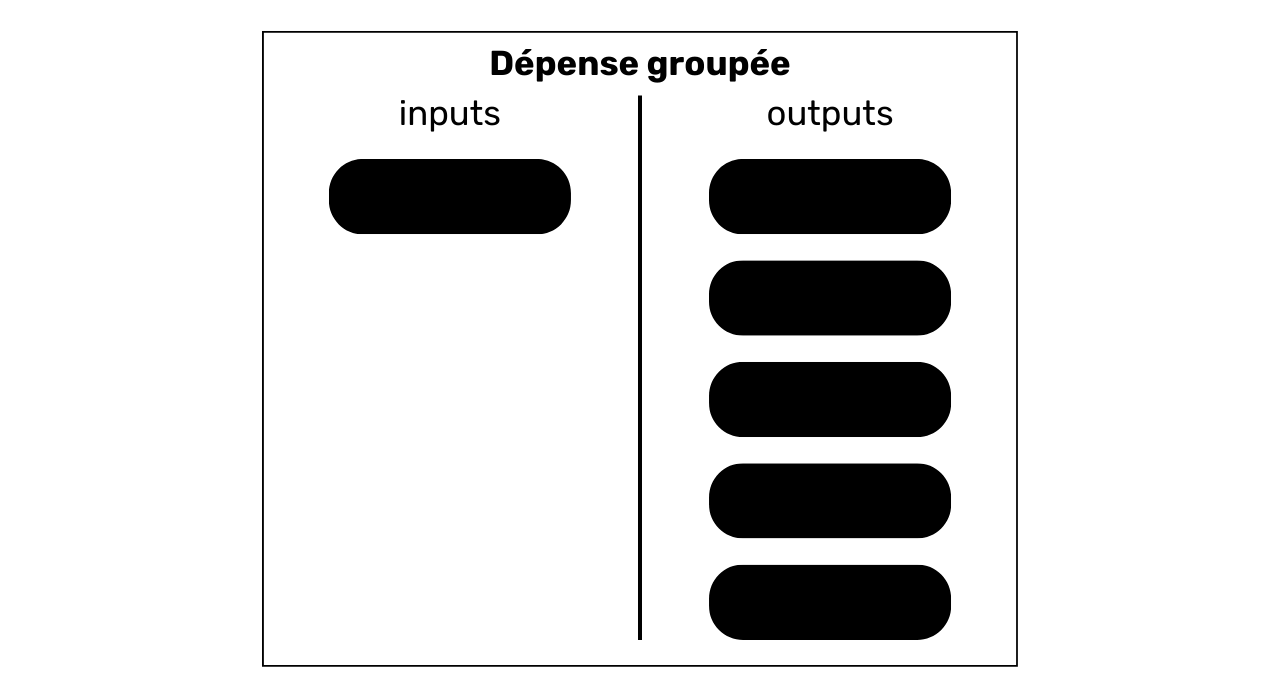

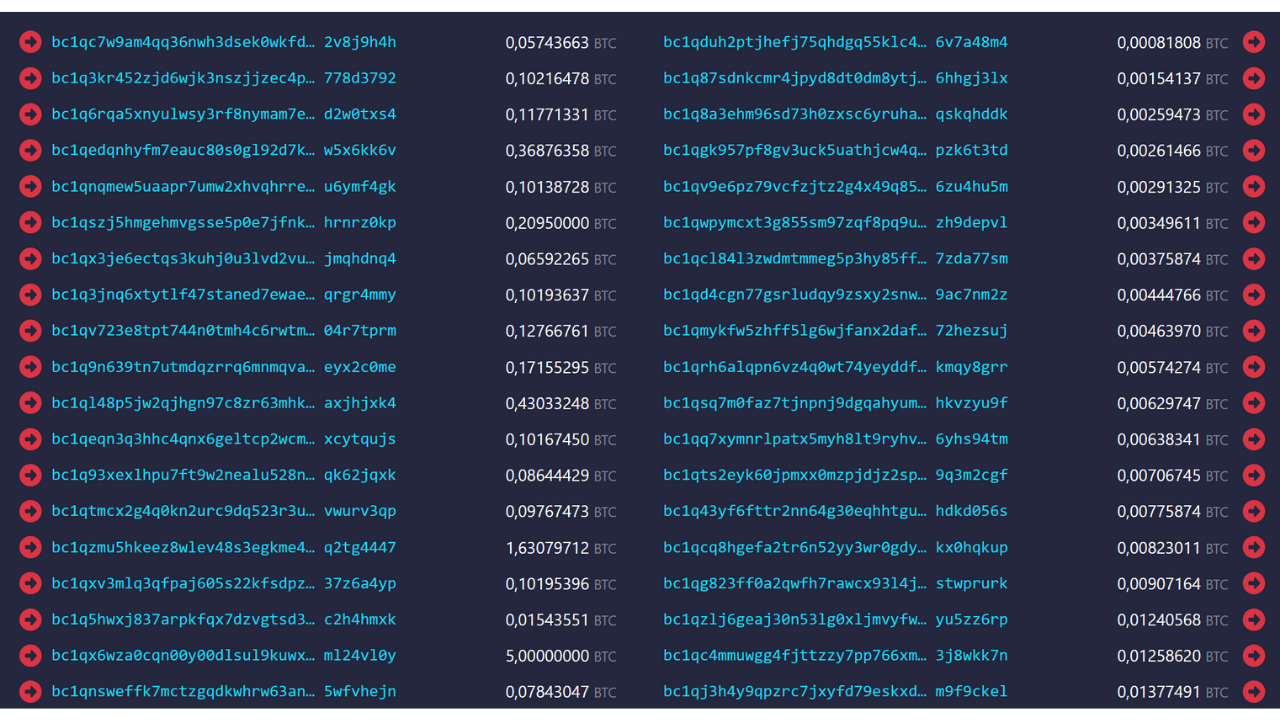

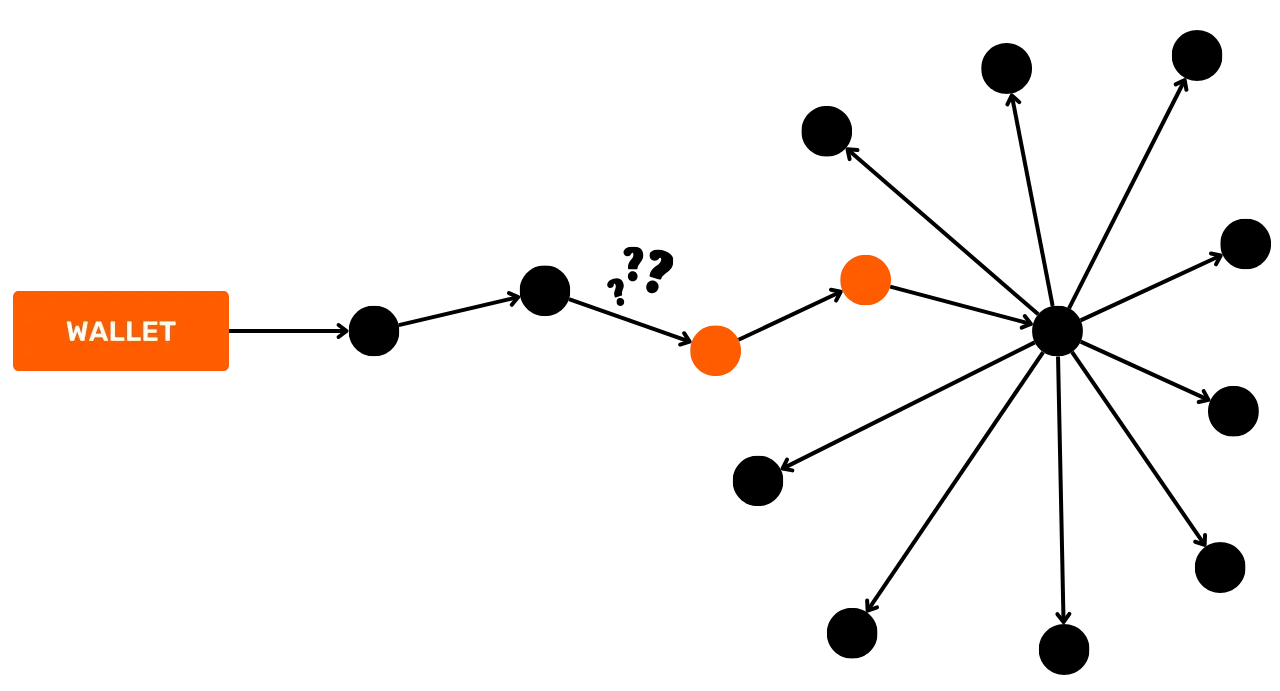

Grouped expenditure

This model is characterized by the consumption of a few UTXOs as inputs (often just one) and the production of many UTXOs as outputs.

The interpretation of this model is that we are in the presence of grouped spending. It's a practice that probably reveals a very large economic activity, such as an exchange platform. Grouped spending enables these entities to save costs by combining their expenses in a single transaction.

We can deduce from this model that the UTXO in input comes from a company with a high level of economic activity, and that the UTXOs in output will disperse. Many will belong to the company's customers who have withdrawn bitcoins from the platform. Others may go to partner companies. Finally, there will certainly be one or more exchanges going back to the issuing company.

For example, here's a Bitcoin transaction that adopts the bundled spend pattern (presumably, it's a transaction issued by the Bybit platform):

8a7288758b6e5d550897beedd13c70bcbaba8709af01a7dbcc1f574b89176b43

Source : Mempool.space

Protocol-specific transactions

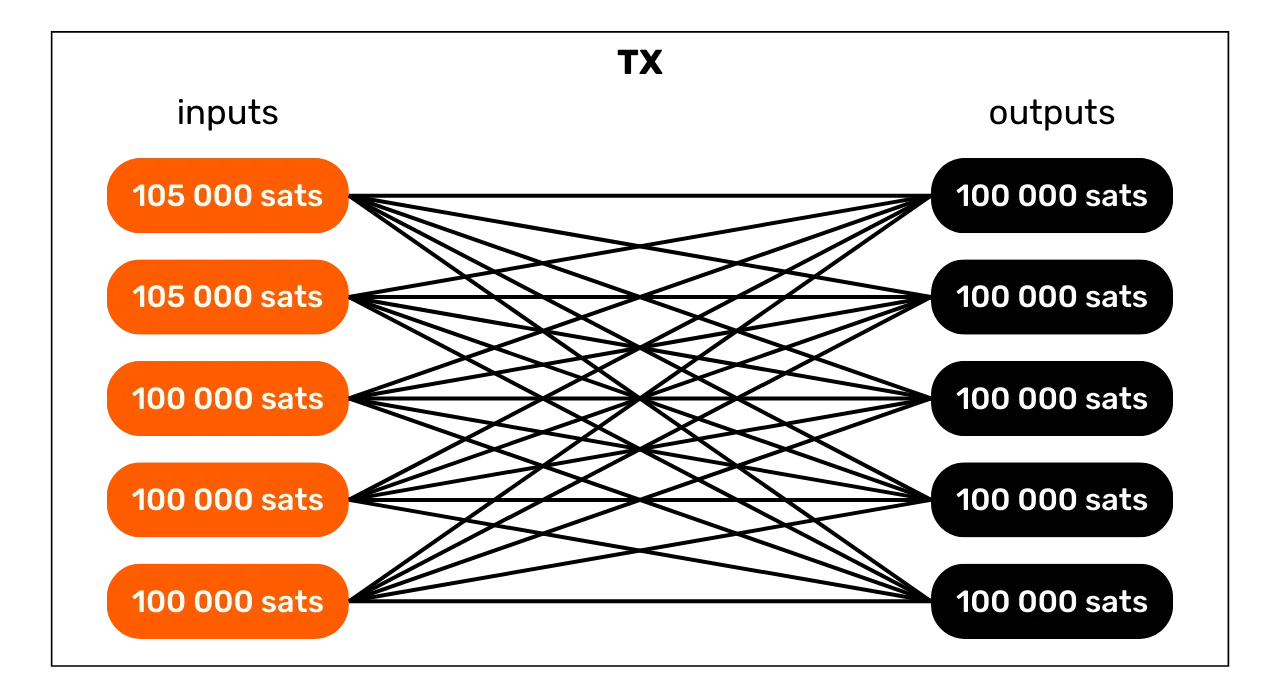

Among transaction patterns, we can also identify those that reveal the use of a specific protocol. For example, Whirlpool coinjoins (discussed in part 5) will have an easily identifiable structure that differentiates them from other, more conventional transactions.

Analysis of this pattern suggests that we are likely to be in the presence of a collaborative transaction. It is also possible to observe a coinjoin. If this latter hypothesis proves correct, then the number of exits could provide us with a rough estimate of the number of participants in the coinjoin.

For example, here is a Bitcoin transaction that adopts the coinjoin collaborative transaction pattern:

00601af905bede31086d9b1b79ee8399bd60c97e9c5bba197bdebeee028b9bea

Source : Mempool.space

There are many other protocols with their own specific structures. For example, there are Wabisabi transactions, Stamps transactions and Runes transactions.

Thanks to these transaction patterns, we can already interpret a certain amount of information about a given transaction. But transaction structure is not the only source of information for analysis. We can also study its details. These internal details are what I like to call "internal heuristics", and we'll be looking at them in the next chapter.

Internal heuristics

An internal heuristic is a specific characteristic that we identify within a transaction itself, without needing to examine its environment, and which enables us to make deductions. Unlike patterns, which focus on the overall structure of the transaction at a high level, internal heuristics are based on the set of extractable data. This includes:

- The amounts of the various UTXOs in and out;

- Everything to do with scripts: reception addresses, versioning, locktimes..

Generally speaking, this type of heuristic will enable us to identify the exchange in a specific transaction. By doing so, we can then perpetuate the tracing of an entity over several different transactions. Indeed, if we identify a UTXO belonging to a user we wish to track, it's crucial to determine, when he carries out a transaction, which output has been transferred to another user and which output represents the exchange, which thus remains in his possession.

Once again, let me remind you that these heuristics are not absolutely precise. Taken individually, they only enable us to identify likely scenarios. It's the accumulation of several heuristics that helps to reduce uncertainty, without ever being able to eliminate it completely.

Internal similarities

This heuristic involves the study of similarities between the inputs and outputs of the same transaction. If the same characteristic is observed on the inputs and on just one of the transaction's outputs, then it is likely that this output constitutes the exchange.

The most obvious feature is the reuse of a receiving address in the same transaction.

This heuristic leaves little room for doubt. Unless he's had his private key hacked, the same receiving address necessarily reveals the activity of a single user. The resulting interpretation is that the transaction exchange is the output with the same address as the input. We can then continue to trace the individual from this exchange.

For example, here is a transaction on which this heuristic can probably be applied:

54364146665bfc453a55eae4bfb8fdf7c721d02cb96aadc480c8b16bdeb8d6d0

Source : Mempool.space

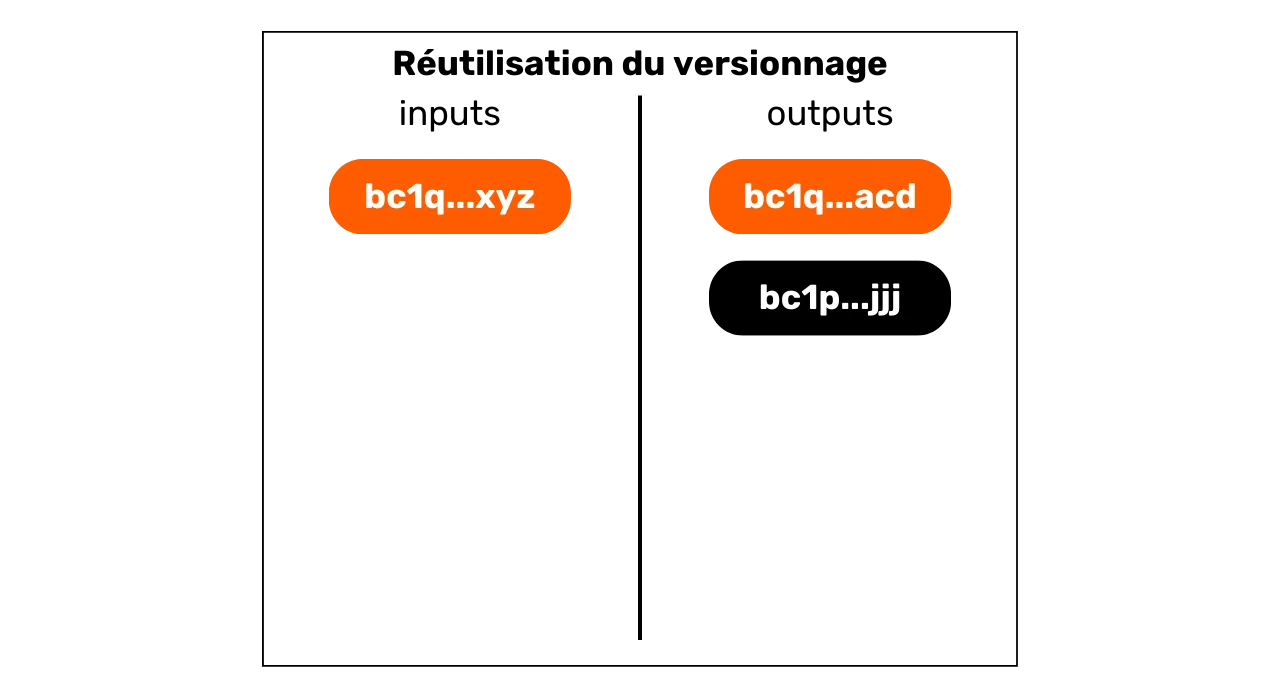

These similarities between inputs and outputs don't stop at address reuse. Any similarity in the use of scripts can be used to apply a heuristic. For example, we can sometimes observe the same versioning between the input and one of the transaction outputs.

On this diagram, we can see that input n° 0 unlocks a P2WPKH script (SegWit

V0 starting with bc1q). Output n° 0 uses the same type of

script. Output n° 1, on the other hand, uses a P2TR script (SegWit V1

beginning with bc1p). The interpretation of this feature is

that it is likely that the address with the same versioning as the input is

the exchange address. It would therefore always belong to the same user.

Here is a transaction on which this heuristic can probably be applied:

db07516288771ce5d0a06b275962ec4af1b74500739f168e5800cbcb0e9dd578

Source : Mempool.space

On the latter, we can see that input no. 0 and output no. 1 use P2WPKH scripts (SegWit V0), while output no. 0 uses a different P2PKH script (Legacy).

In the early 2010s, this heuristic based on script versioning was relatively

unhelpful due to the limited types of scripts available. However, over time

and with successive Bitcoin updates, an increasing diversity of script types

has been introduced. This heuristic is therefore becoming increasingly

relevant, as with a wider range of script types, users divide into smaller

groups, thus increasing the chances of applying this internal versioning

reuse heuristic. For this reason, from a confidentiality perspective only,

it's advisable to opt for the most common type of script. For example, as I

write these lines, Taproot scripts (bc1p) are less frequently

used than SegWit V0 scripts (bc1q). Although the former offer

economic and confidentiality benefits in certain specific contexts, for more

traditional single-signature uses, it may make sense to stick with an older

standard for confidentiality reasons, until the new standard is more widely

adopted.

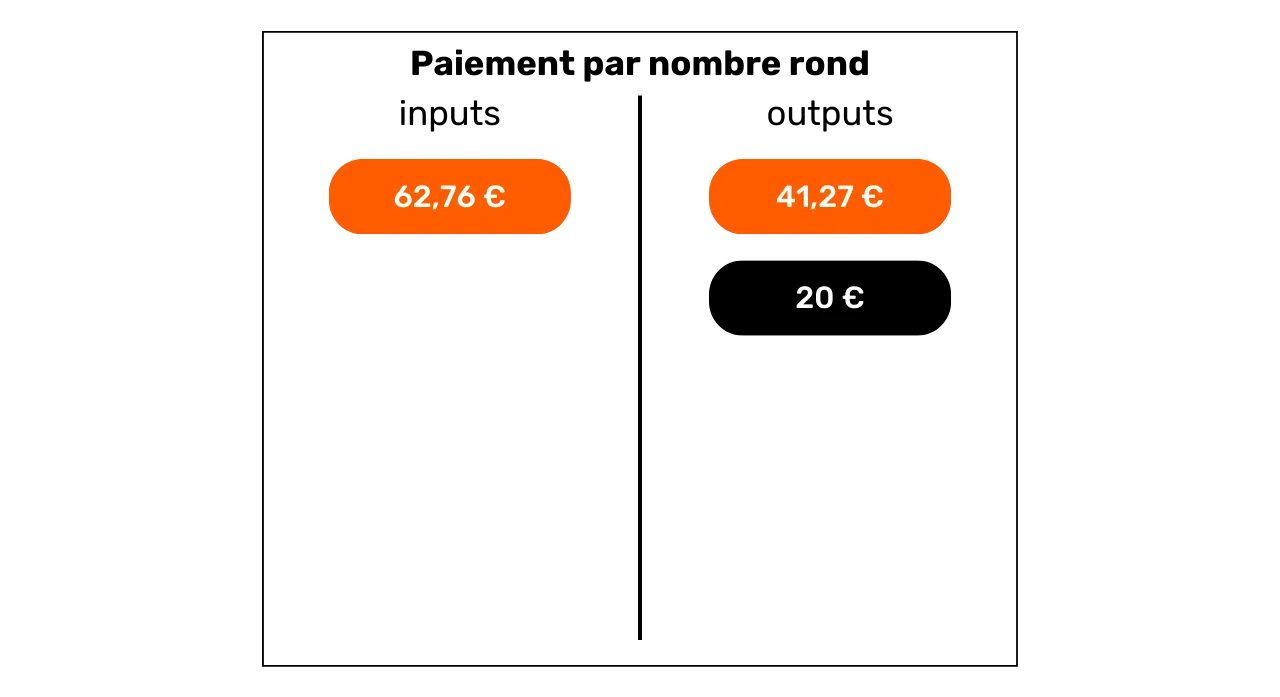

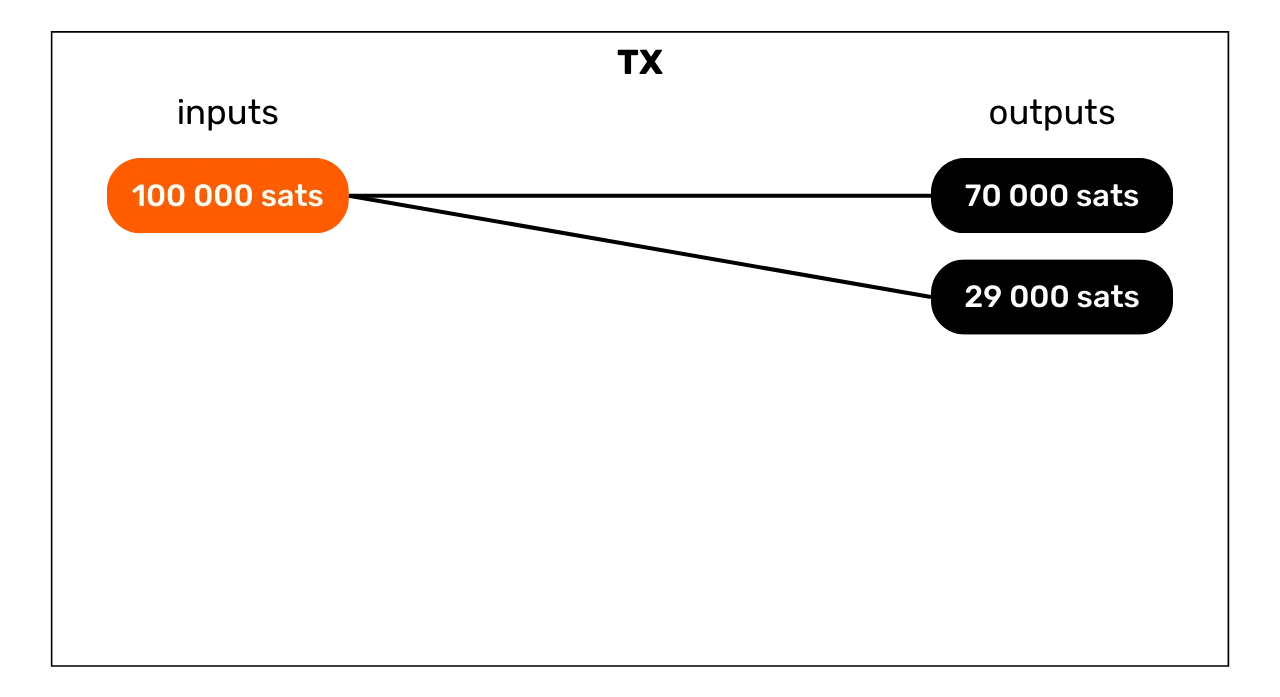

Round number payments

Another internal heuristic that can help us identify the exchange is the round number heuristic. Generally speaking, when faced with a simple payment pattern (1 input and 2 outputs), if one of the outputs spends a round amount, then this represents the payment.

By elimination, if one output represents payment, the other represents exchange. It can therefore be interpreted as likely that the input user is always in possession of the output identified as the exchange.

It should be stressed that this heuristic is not always applicable, since the majority of payments are still made in fiduciary units of account. Indeed, when a retailer in France accepts bitcoin, he will generally not display stable prices in sats. Instead, he will opt for a conversion between the price in euros and the amount in bitcoins to be paid. There should therefore be no round numbers at the end of the transaction.

Nevertheless, an analyst could try to make this conversion taking into

account the exchange rate in effect when the transaction was broadcast on

the network. Let's take the example of a transaction with an input of 97,552 sats and two outputs, one of 31,085 sats and the other of 64,152 sats. At first glance, this transaction does not appear

to involve round amounts. However, by applying the exchange rate of €64,339

at the time of the transaction, we obtain a conversion into euros as

follows:

- An input of €62.76;

- An output of €20;

- An output of €41.27.

Once converted into fiat currency, this transaction can be used to apply the round amount payment heuristic. The €20 output probably went to a merchant, or at least changed ownership. By deduction, the €41.27 output is likely to have remained in the possession of the original user.

If, one day, bitcoin becomes the preferred unit of account in our exchanges, this heuristic could become even more useful for analysis.

For example, here is a transaction on which this heuristic can probably be applied:

2bcb42fab7fba17ac1b176060e7d7d7730a7b807d470815f5034d52e96d2828a

Source : Mempool.space

The largest output

When we identify a sufficiently large gap between 2 transaction outputs on a simple payment model, we can estimate that the largest output is likely to be foreign exchange.

This largest output heuristic is surely the most imprecise of all. On its own, it's pretty weak. However, this feature can be combined with other heuristics to reduce the uncertainty of our interpretation.

For example, if we're looking at a transaction with a round payment and a larger payment, applying the round payment heuristic and the larger payment heuristic together reduces our level of uncertainty.

For example, here is a transaction on which this heuristic can probably be applied:

b79d8f8e4756d34bbb26c659ab88314c220834c7a8b781c047a3916b56d14dcf

Source : Mempool.space

External heuristics

The study of external heuristics means analyzing the similarities, patterns and characteristics of certain elements that are not specific to the transaction itself. In other words, while we previously limited ourselves to exploiting elements intrinsic to the transaction with internal heuristics, we are now broadening our field of analysis to include the transaction's environment, thanks to external heuristics.

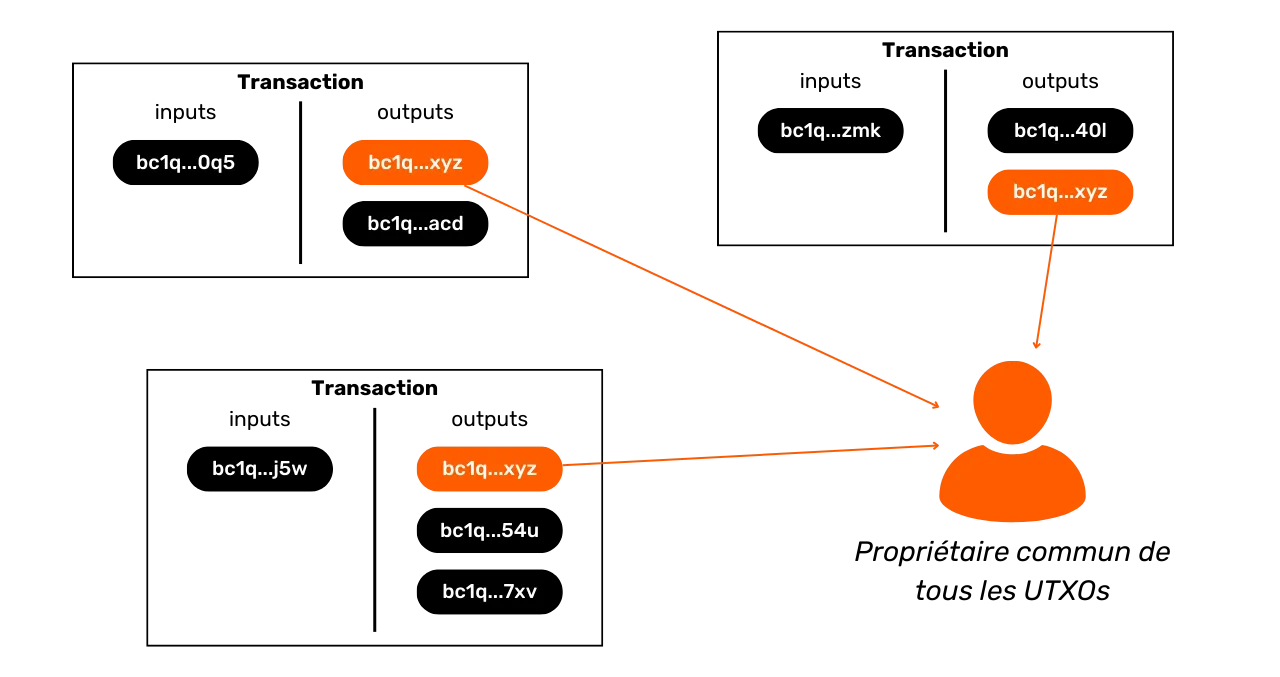

Address reuse

This is one of bitcoiners' best-known heuristics. Address reuse makes it possible to establish a link between different transactions and different UTXOs. It occurs when a Bitcoin receiving address is used several times.

Thus, it is possible to exploit address reuse within the same transaction as an internal heuristic to identify the exchange (as we saw in the previous chapter). But address reuse can also be used as an external heuristic to recognize the uniqueness of an entity behind several transactions.

The interpretation of the reuse of an address is that all UTXOs blocked on that address belong (or have belonged) to the same entity. This heuristic leaves little room for uncertainty. Once identified, the resulting interpretation is likely to correspond to reality. It therefore enables the grouping of different onchain activities.

As explained in the introduction to Part 3, this heuristic was discovered by Satoshi Nakamoto himself. In the White Paper, he mentions a solution to help users avoid generating it, which is simply to use a blank address for each new transaction:

"As an additional firewall, a new key pair could be used for each transaction to keep them unlinked to a common owner."

Source: S. Nakamoto, "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System", https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf, 2009.

For example, here is an address that is reused in several transactions:

bc1qqtmeu0eyvem9a85l3sghuhral8tk0ar7m4a0a0

Source : Mempool.space

Script similarity and wallet imprints

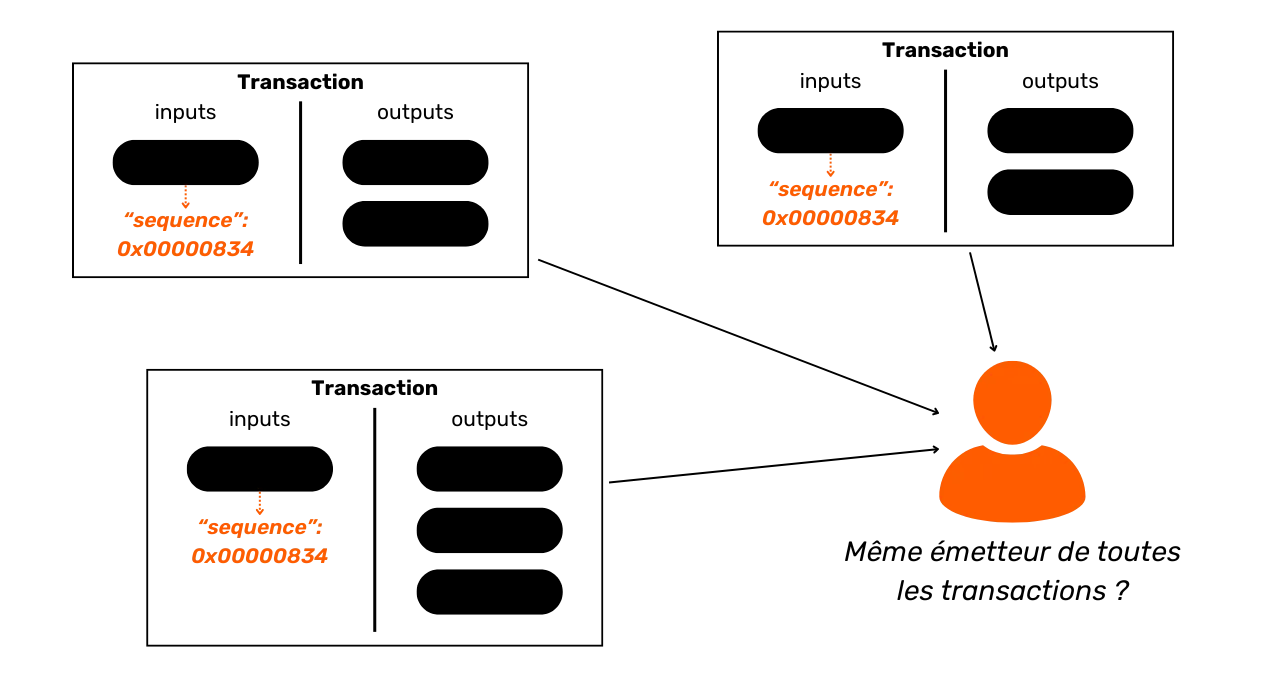

In addition to address reuse, there are many other heuristics that allow you to link actions to the same portfolio or address cluster.

Firstly, an analyst can look for similarities in script usage. For example, certain minority scripts such as multisig may be easier to spot than SegWit V0 scripts. The larger the group we're hiding in, the harder it is to spot us. This is one of the reasons why, on good Coinjoin protocols, all participants use exactly the same type of script.

More generally, an analyst can also focus on the characteristic fingerprints of a portfolio. These are use-specific processes that can be identified with a view to exploiting them as tracing heuristics. In other words, if we observe an accumulation of the same internal characteristics on transactions attributed to the traced entity, we can attempt to identify these same characteristics on other transactions.

For example, we'll be able to identify that the traced user systematically

sends his change to P2TR addresses (bc1p...). If this process

is repeated, we can use it as a heuristic for the rest of our analysis. We

can also use other fingerprints, such as the order of UTXOs, the place of

the change in the outputs, RBF (Replace-by-Fee) signaling, or the version

number, the nSequence field and the nLockTime field.

As @LaurentMT points out in Space Kek #19 (a French-language podcast), the usefulness of portfolio fingerprints in chain analysis is increasing significantly over time. Indeed, the growing number of script types and the increasingly progressive deployment of these new features by portfolio software accentuate the differences. In some cases, it is even possible to identify the exact software used by the entity being tracked. It is therefore important to understand that the study of portfolio footprints is particularly relevant for recent transactions, rather than those initiated in the early 2010s.

To sum up, a footprint can be any specific practice, performed automatically by the wallet or manually by the user, that we can find on other transactions to help us in our analysis.

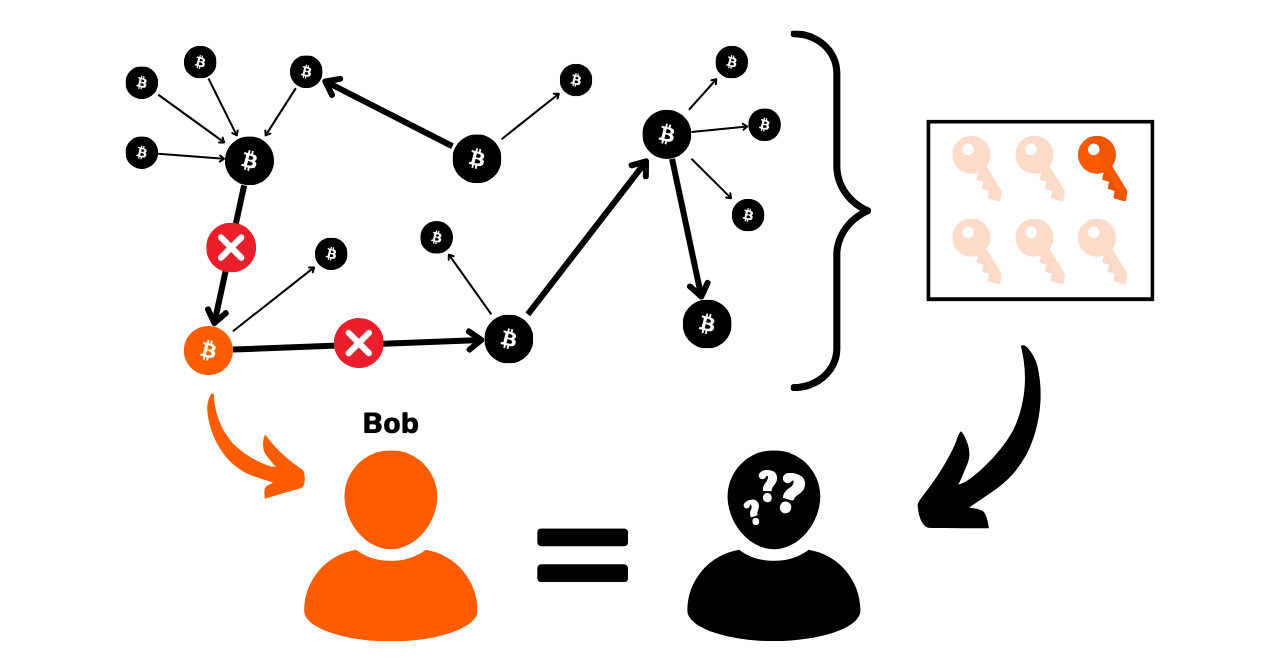

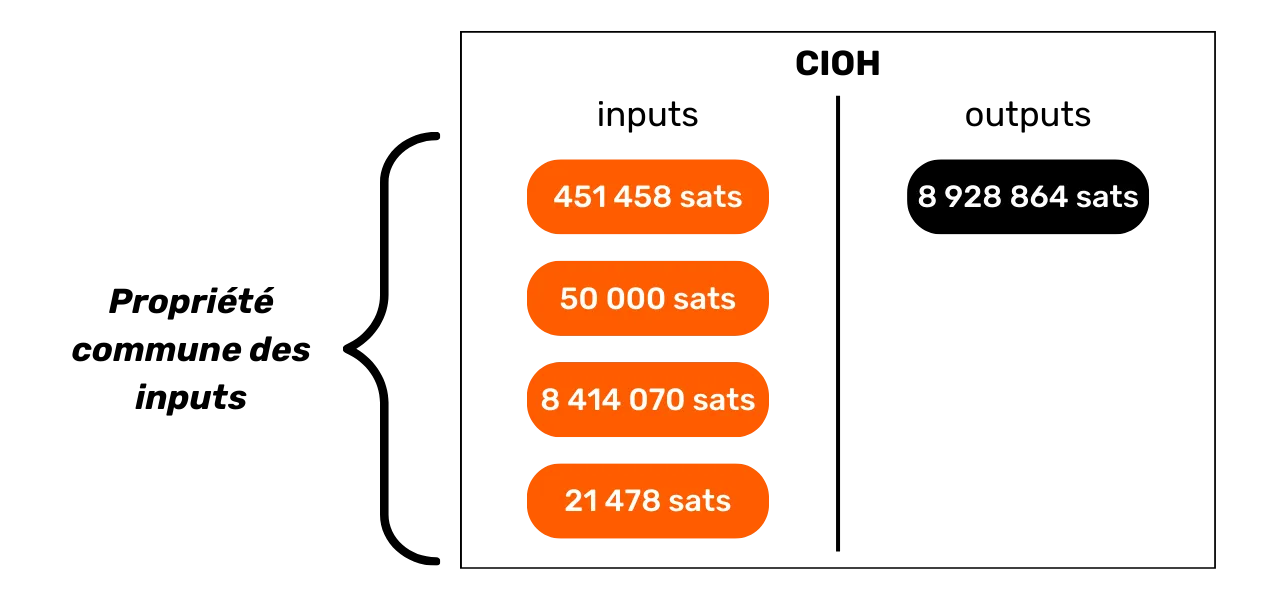

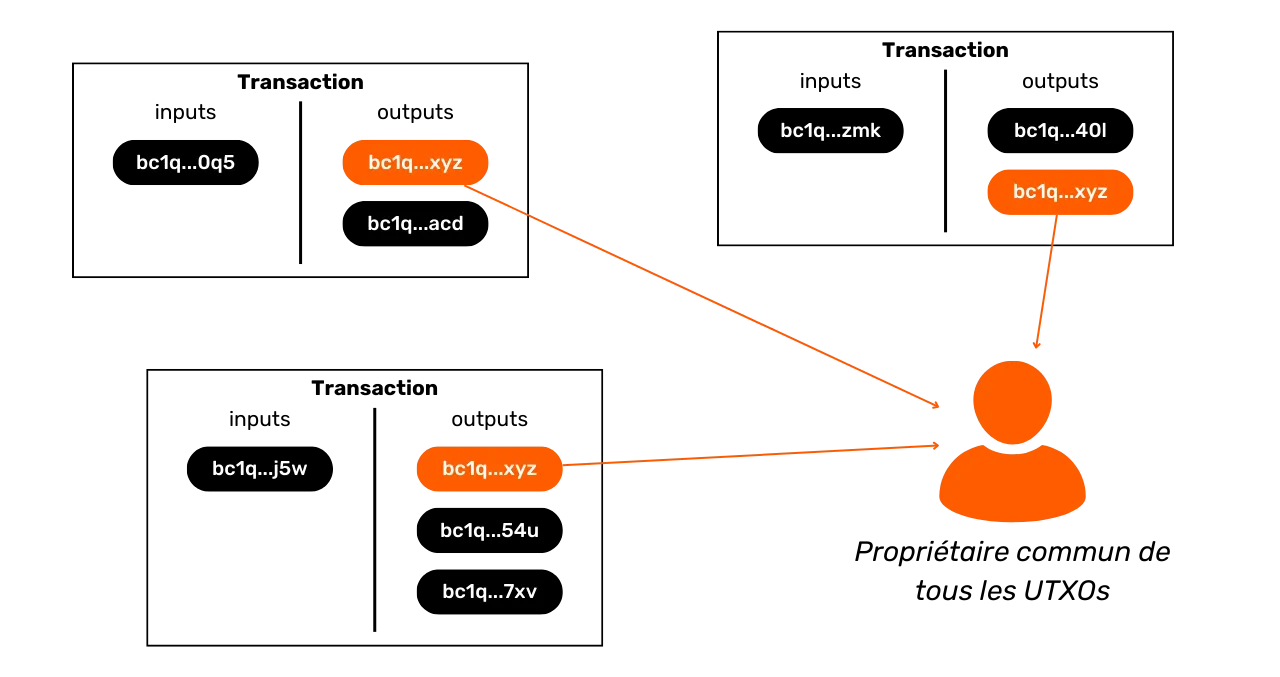

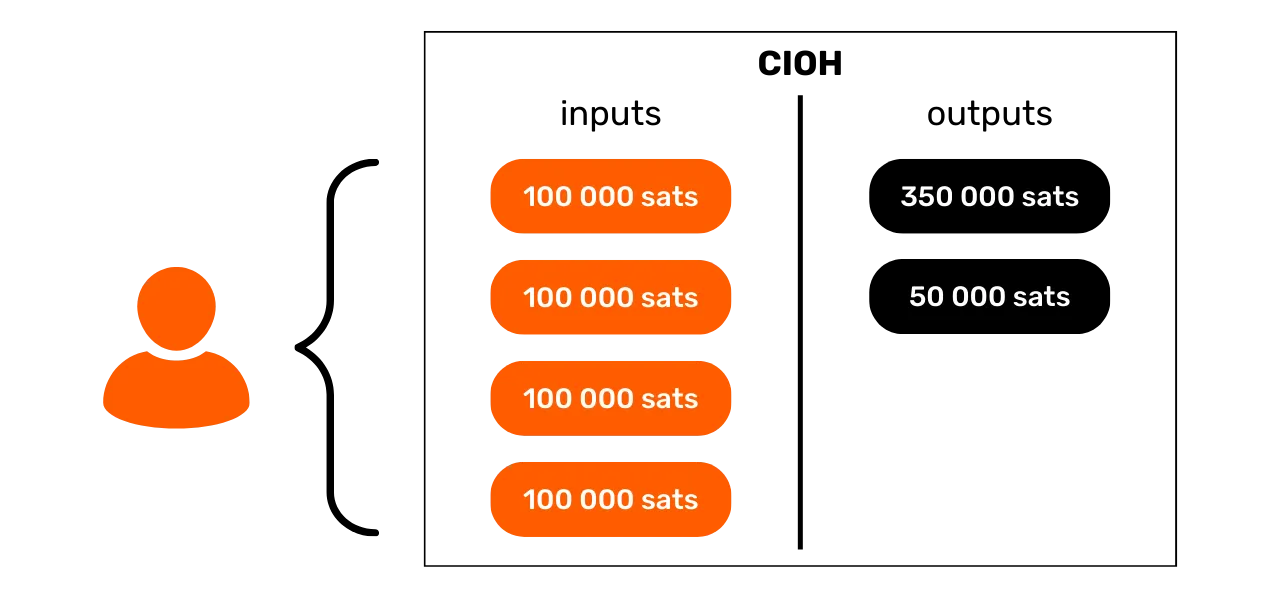

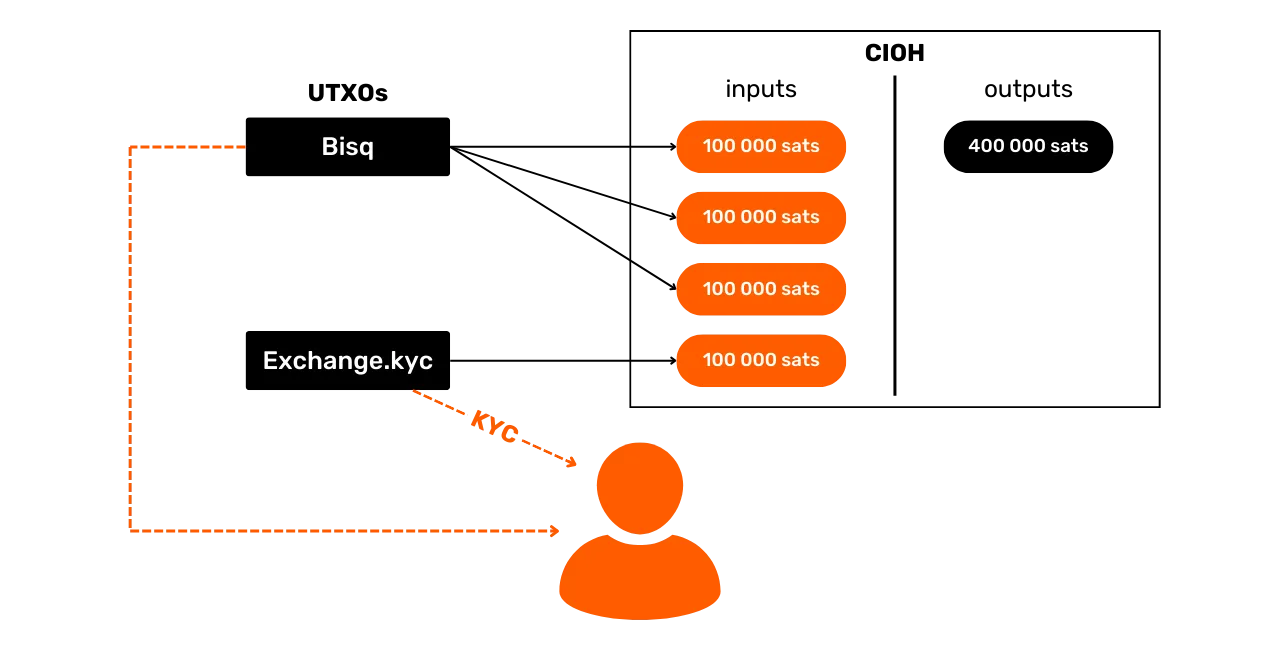

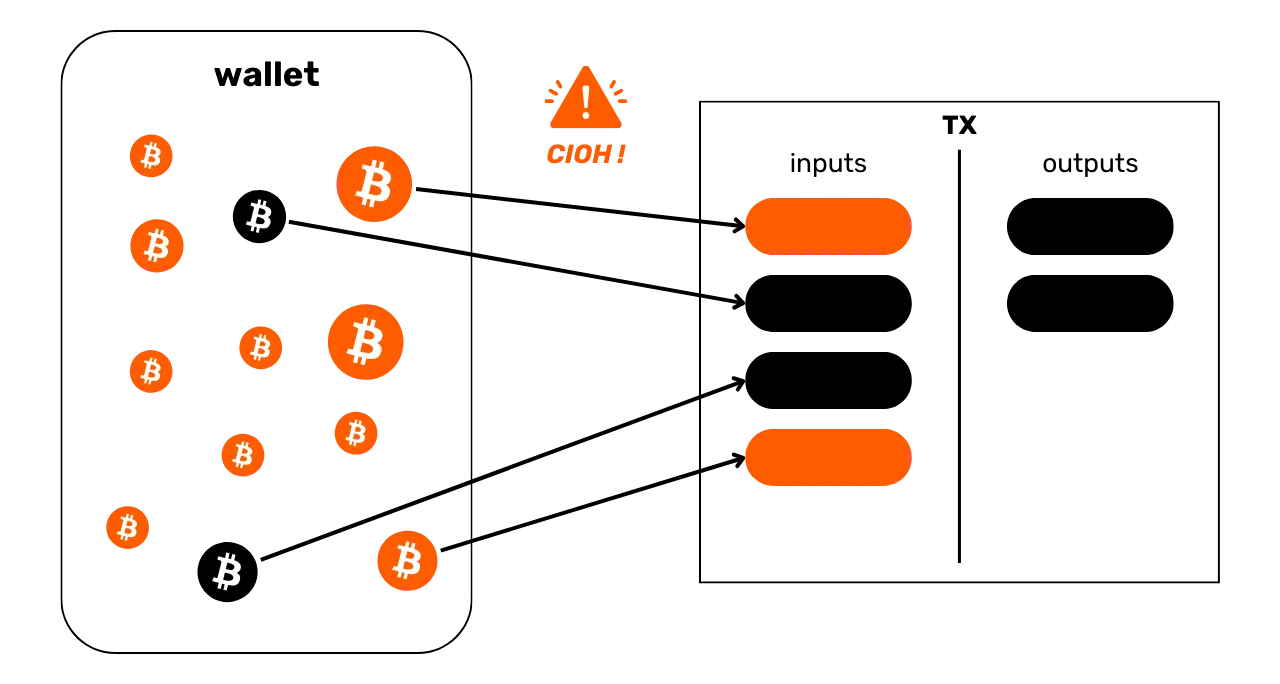

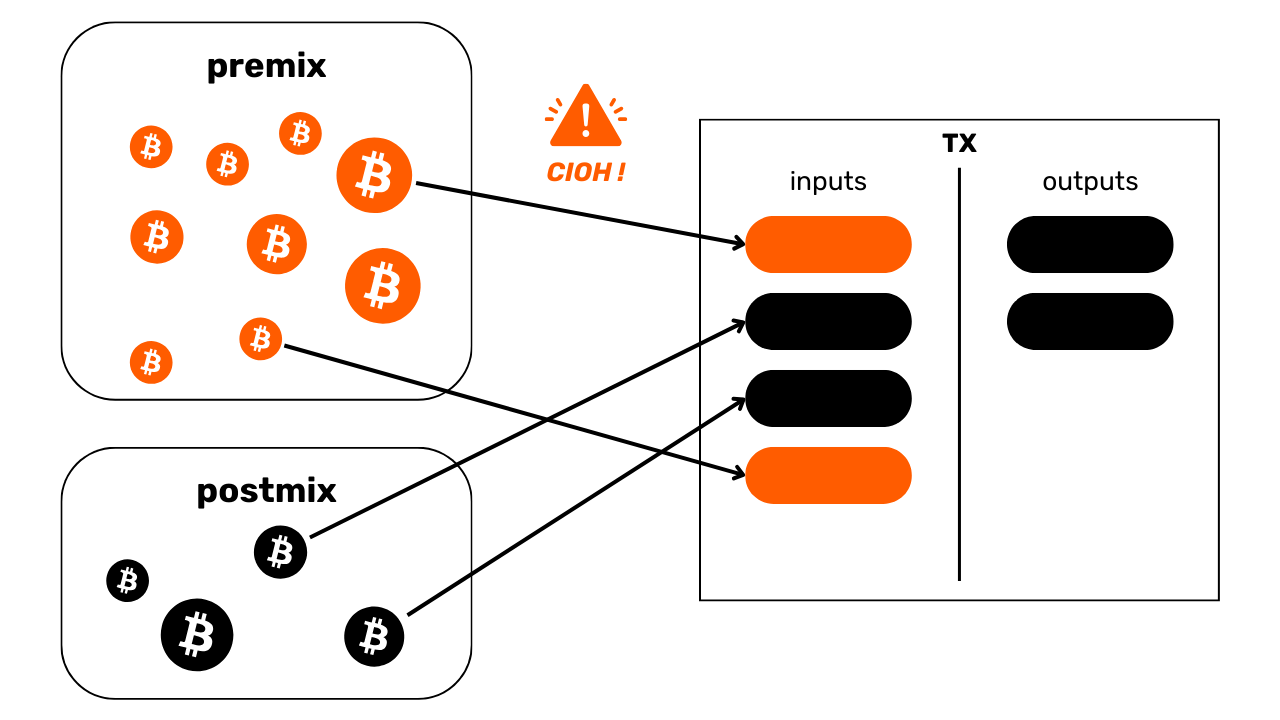

The Common Input Ownership Heuristic (CIOH)

The Common Input Ownership Heuristic (CIOH) is a heuristic that states that when a transaction has multiple inputs, they are all likely to emanate from a single entity. Consequently, their ownership is common.

To apply the CIOH, we first observe a transaction with several inputs. This could be 2 inputs, or 30 inputs. Once this characteristic has been identified, we check whether the transaction fits into a known transaction model. For example, if there are 5 inputs with roughly the same amount and 5 outputs with exactly the same amount, we'll know that this is the structure of a coinjoin. We won't be able to apply the CIOH.

On the other hand, if the transaction doesn't fit into any known collaborative transaction model, then we can interpret that all inputs are likely to come from the same entity. This can be very useful for extending an already known cluster or continuing a trace.

CIOH was discovered by Satoshi Nakamoto. He talks about it in part 10 of the White Paper:

"[...] linking is inevitable with multi-entry transactions, which necessarily reveal that their entries were held by the same owner. The risk is that if the owner of a key is revealed, the links may reveal other transactions that belonged to the same owner."

It's particularly fascinating to note that Satoshi Nakamoto, even before the official launch of Bitcoin, had already identified the two main privacy vulnerabilities for users, namely CIOH and address reuse. Such foresight is quite remarkable, as these two heuristics remain, even today, the most useful in blockchain analysis.

To give you an example, here is a transaction on which we can probably apply CIOH:

20618e63b6eed056263fa52a2282c8897ab2ee71604c7faccfe748e1a202d712

Source : Mempool.space

Off-chain data

Of course, chain analysis is not limited exclusively to onchain data. Any data from a previous analysis or available on the Internet can also be used to refine an analysis.

For example, if we observe that traced transactions are systematically broadcast from the same Bitcoin node, and we manage to identify its IP address, we may be able to identify other transactions from the same entity, as well as determining part of the issuer's identity. Although this practice is not easily achievable, as it requires the operation of numerous nodes, it may be employed by some companies specializing in blockchain analysis.

The analyst also has the option of relying on analyses previously made open-source, or on his own previous analyses. Perhaps we'll be able to find an output that points to a cluster of addresses we've already identified. Sometimes, it's also possible to rely on outputs that point to an exchange platform, as the addresses of these companies are generally known.

In the same way, you can perform an analysis by elimination. For example, if when analyzing a transaction with two outputs, one of them relates to an address cluster already known, but distinct from the entity we're tracing, then we can interpret that the other output probably represents the exchange.

Channel analysis also includes a slightly more general OSINT (Open Source Intelligence) component, involving internet searches. It is for this reason that we advise against publishing addresses directly on social networks or on a website, whether pseudonymous or not.

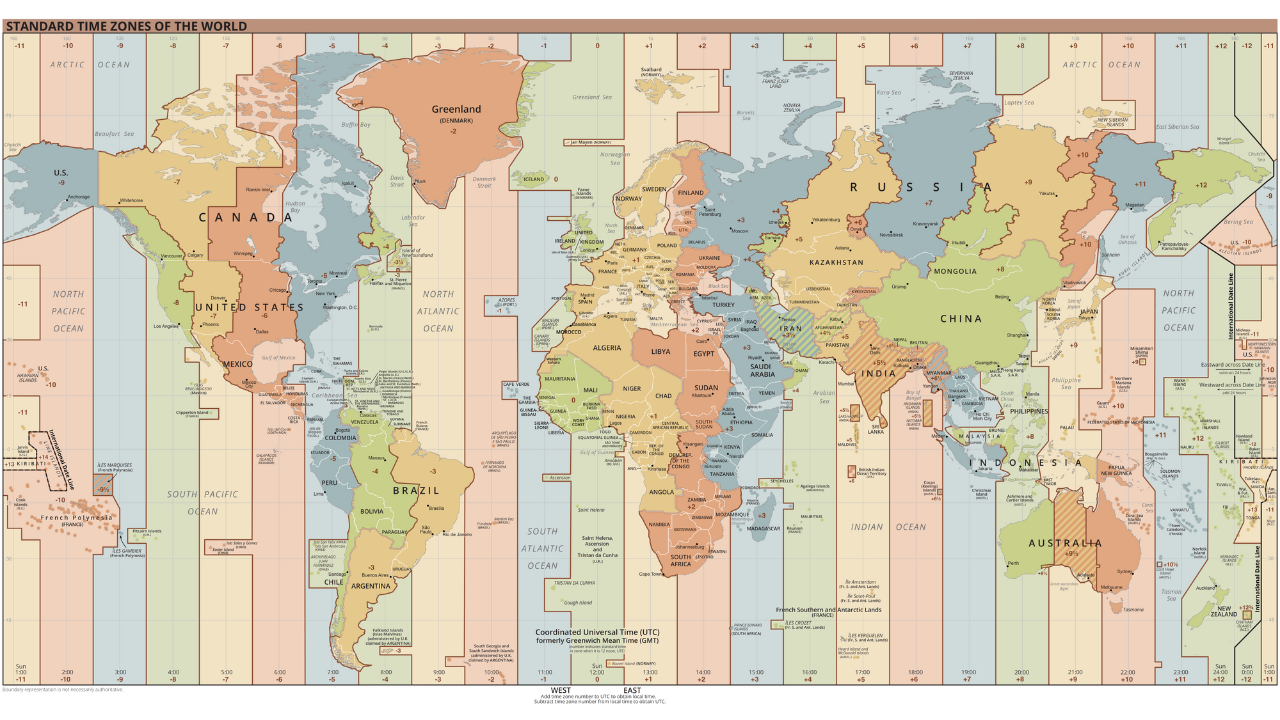

Temporal models

We think about it less, but certain human behaviors are recognizable onchain. Perhaps the most useful in an analysis is your sleep pattern! Yes, when you sleep, you don't broadcast Bitcoin transactions. But you generally sleep at roughly the same time. This is why it's common practice to use temporal analysis in blockchain analysis. Quite simply, this is a census of the times at which a given entity's transactions are broadcast to the Bitcoin network. By analyzing these temporal patterns, we can deduce a wealth of information.

First of all, a temporal analysis can sometimes identify the nature of the traced entity. If we observe that the transactions are broadcast consistently over 24 hours, then this will betray a high level of economic activity. The entity behind these transactions is likely to be a company, potentially international and perhaps with automated in-house procedures.

For example, I recognized this pattern a few months ago when analyzing the transaction that had mistakenly allocated 19 bitcoins in fees. A simple temporal analysis allowed me to hypothesize that we were dealing with an automated service, and therefore probably with a large entity such as an exchange platform.

Indeed, a few days later, it was discovered that the funds belonged to PayPal, via the Paxos exchange platform.

On the contrary, if we can see that the temporal pattern is rather spread over 16 specific hours, then we can estimate that we're dealing with an individual user, or perhaps a local company depending on the volumes exchanged.

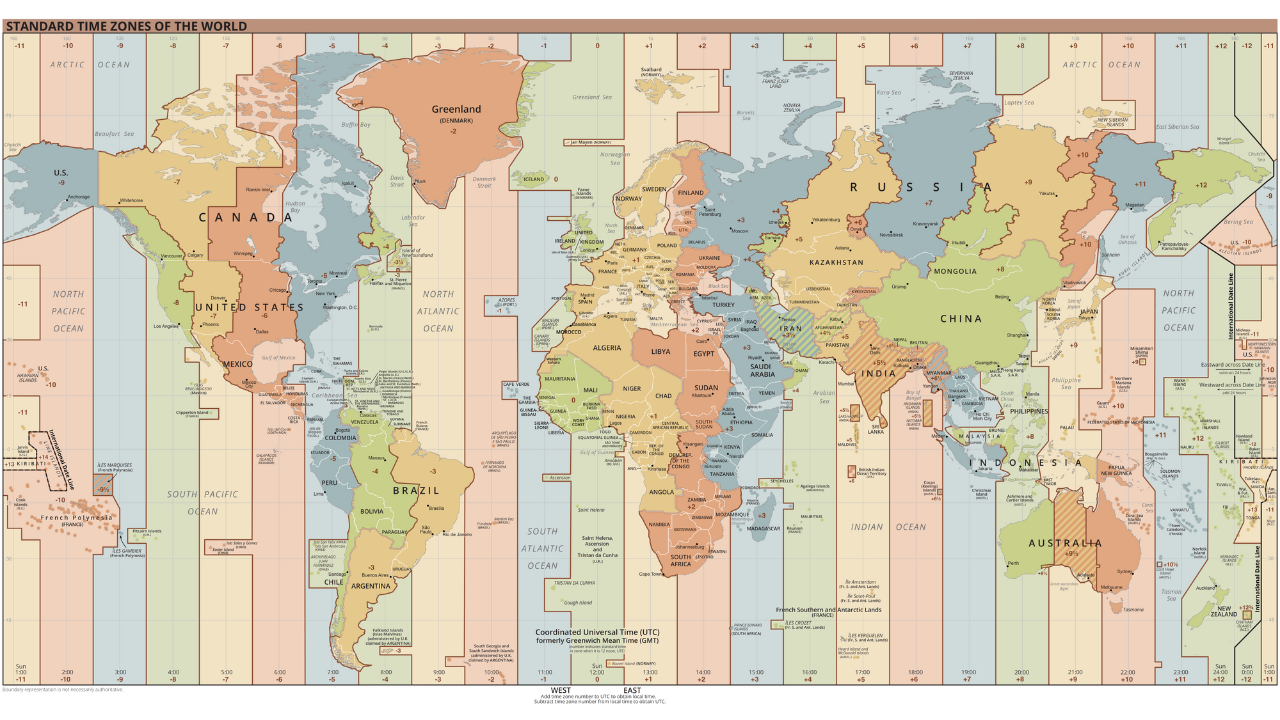

Beyond the nature of the entity observed, the temporal pattern can also tell us approximately where the user is located, thanks to time zones. In this way, we can match other transactions, and use their timestamps as an additional heuristic that can be added to our analysis.

For example, on the multi-used address I mentioned earlier, we can see that transactions, both incoming and outgoing, are concentrated on a 13-hour interval.

bc1qqtmeu0eyvem9a85l3sghuhral8tk0ar7m4a0a0

Source : OXT.me

This range probably corresponds to Europe, Africa or the Middle East. We can therefore assume that the user behind these transactions lives in these areas.

In a different vein, a time analysis of this type also led to the hypothesis that Satoshi Nakamoto was not operating from Japan, but from the USA: The Time Zones of Satoshi Nakamoto

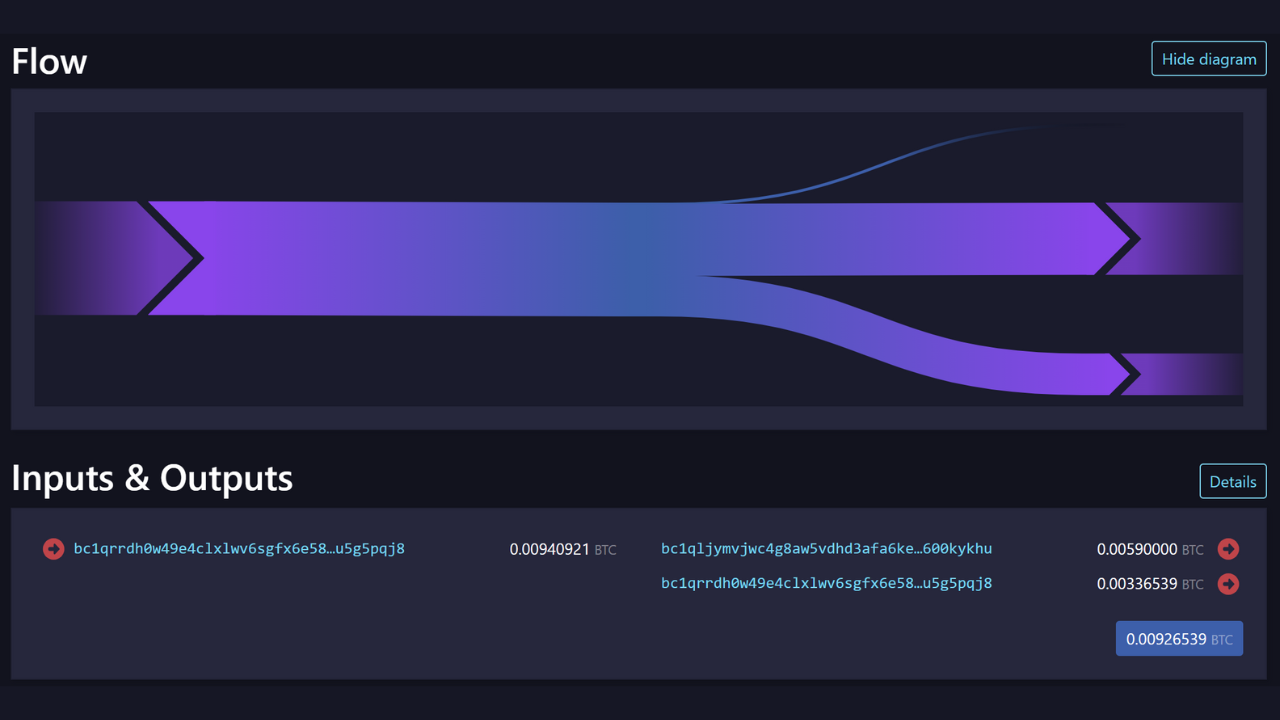

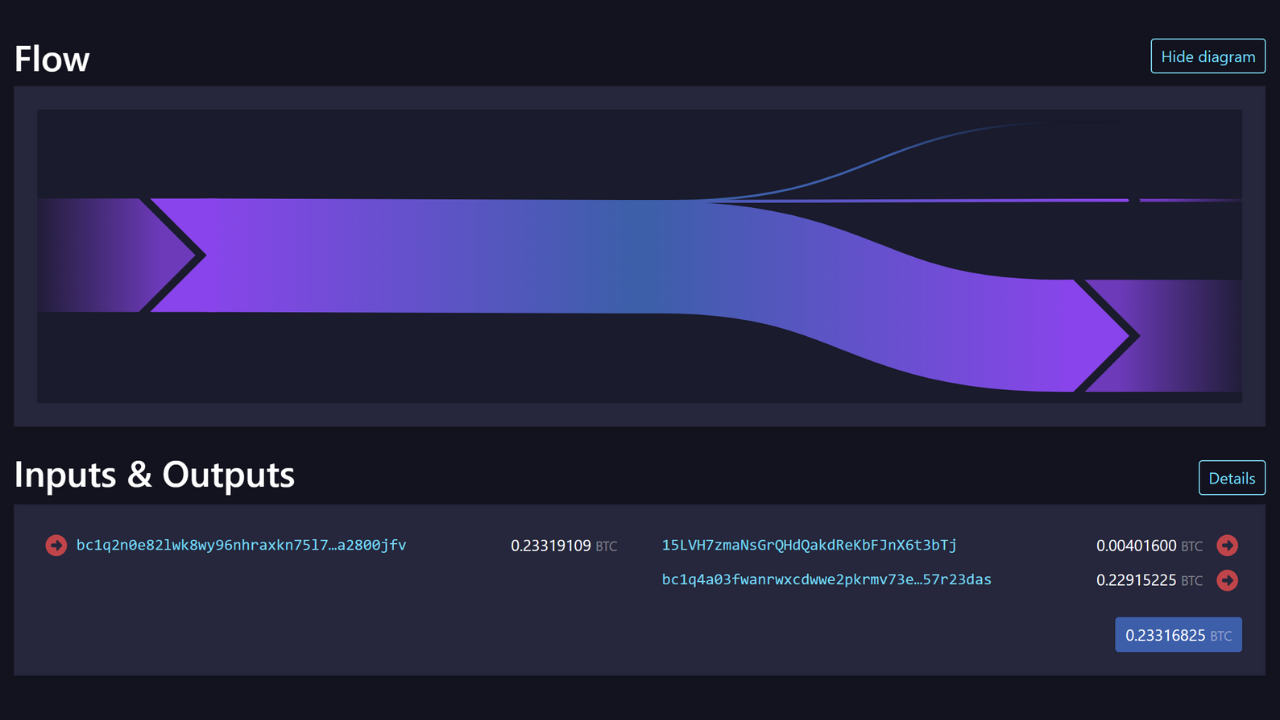

Putting it into practice with a block explorer

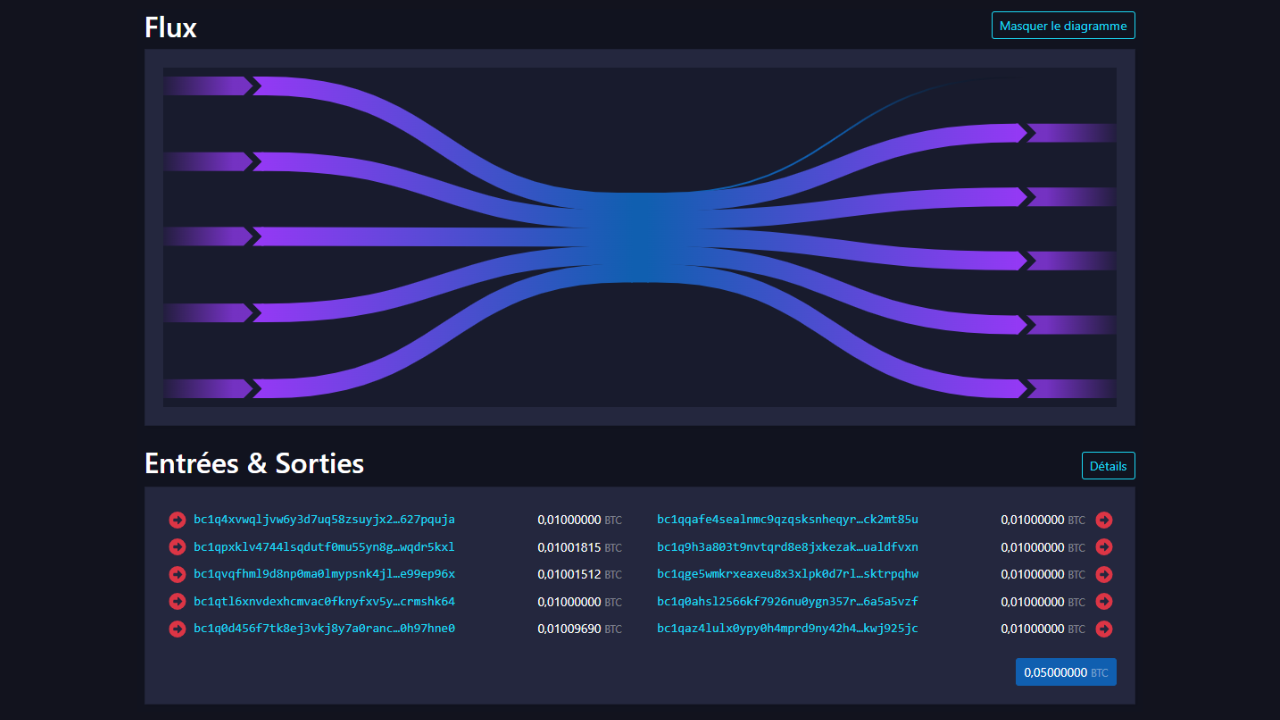

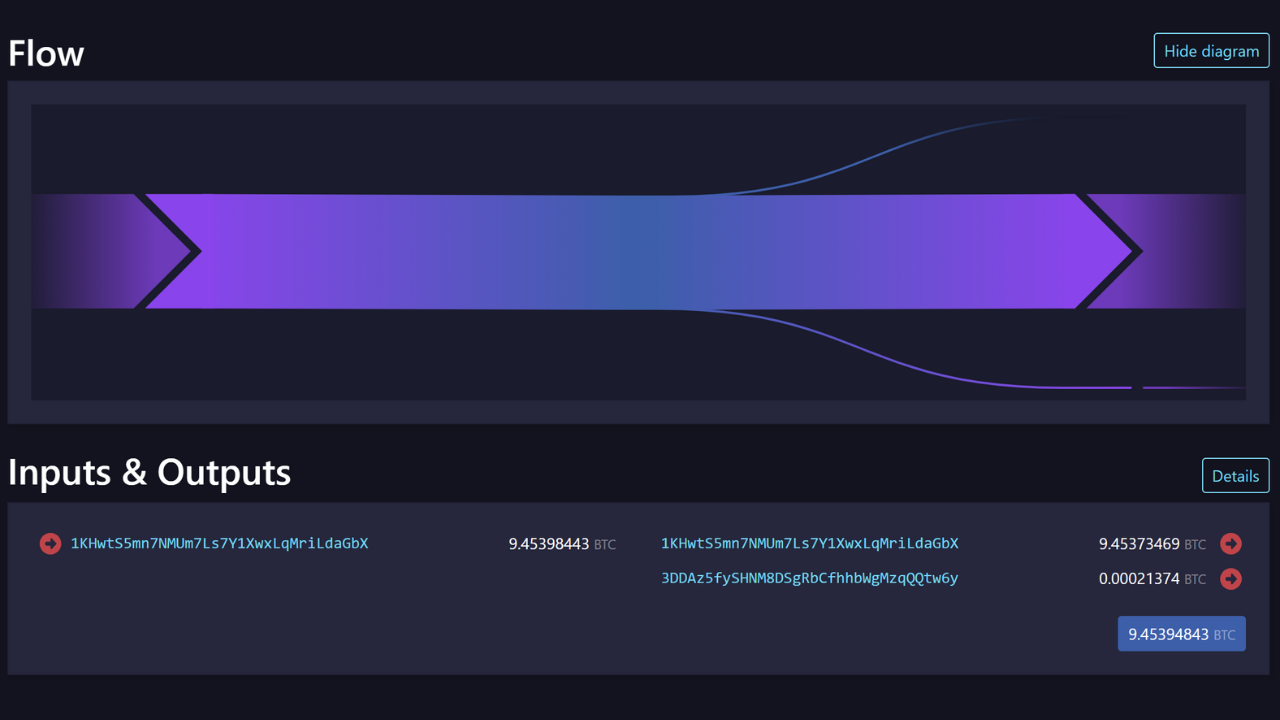

In this final chapter, we're going to put the concepts we've studied so far into practice. I'm going to show you examples of real Bitcoin transactions, and you'll have to extract the information I'm asking you for.

Ideally, to perform these exercises, the use of a professional chain analysis tool would be preferable. However, since the arrest of the creators of Samourai Wallet, the only free analysis tool OXT.me is no longer available. We'll therefore opt for a classic block explorer for these exercises. I recommend using Mempool.space for its many features and range of chain analysis tools, but you can also opt for another explorer such as Bitcoin Explorer.

To begin with, I'll introduce you to the exercises. Use your block explorer to complete them, and write down your answers on a sheet of paper. Then, at the end of this chapter, I'll provide you with the answers so you can check and correct your results.

The transactions selected for these exercises have been chosen purely for their characteristics in a somewhat random fashion. This chapter is intended for educational and informative purposes only. I would like to make it clear that I neither support nor encourage the use of these tools for malicious purposes. The aim is to teach you how to protect yourself against string analysis, not to conduct analysis to expose other people's private information.

Exercise 1

Identifier of the transaction to be analyzed :

3769d3b124e47ef4ffb5b52d11df64b0a3f0b82bb10fd6b98c0fd5111789bef7

What is the name of this transaction's model, and what plausible interpretations can be drawn by examining only its model, i.e. the structure of the transaction?

Exercise 2

Identifier of the transaction to be analyzed :

baa228f6859ca63e6b8eea24ffad7e871713749d693ebd85343859173b8d5c20

What is the name of this transaction's model, and what plausible interpretations can be drawn by examining only its model, i.e. the structure of the transaction?

Exercise 3

Identifier of the transaction to be analyzed :

3a9eb9ccc3517cc25d1860924c66109262a4b68f4ed2d847f079b084da0cd32b

What is the model for this transaction?

Having identified its model, using the transaction's internal heuristics, what output is the exchange likely to represent?

Exercise 4

Identifier of the transaction to be analyzed :

35f0b31c05503ebfdf7311df47f68a048e992e5cf4c97ec34aa2833cc0122a12

What is the model for this transaction?

Having identified its model, using the transaction's internal heuristics, what output is the exchange likely to represent?

Exercise 5

Let's imagine that Loïc has posted one of his Bitcoin receiving addresses on the social network Twitter :

bc1qja0hycrv7g9ww00jcqanhfpqmzx7luqalum3vu

Based on this information and using only the address reuse heuristic, which Bitcoin transactions can be linked to Loïc's identity?

Obviously, I'm not the real owner of this reception address and I didn't post it on social networks. It's an address I took randomly from the blockchain

Exercise 6

Following exercise 5, thanks to the address reuse heuristic, you were able to identify several Bitcoin transactions in which Loïc seems to be involved. Normally, among the transactions identified, you should have spotted this one:

2d9575553c99578268ffba49a1b2adc3b85a29926728bd0280703a04d051eace

This transaction is the very first to send funds to Loïc's address. Where do you think the bitcoins received by Loïc via this transaction came from?

Exercise 7

Following exercise 5, thanks to the address reuse heuristic, you've been able to identify several Bitcoin transactions in which Loïc seems to be involved. Now you want to find out where Loïc came from. Based on the transactions found, perform a time analysis to find the time zone most likely used by Loïc. From this time zone, determine a location where Loïc seems to live (country, state/region, city...).

Exercise 8

Here is the Bitcoin transaction to study:

bb346dae645d09d32ed6eca1391d2ee97c57e11b4c31ae4325bcffdec40afd4f

Looking at this transaction alone, what information can we interpret?

Exercise solutions

Exercise 1:

The model for this transaction is the simple payment model. If we study only its structure, we can interpret that one output represents the exchange and the other output represents an actual payment. We therefore know that the observed user is probably no longer in possession of one of the two UTXOs in output (that of payment), but is still in possession of the other UTXO (that of exchange).

Exercise 2:

The model for this transaction is that of grouped spending. This model probably reveals a large-scale economic activity, such as an exchange platform. We can deduce that the input UTXO comes from a company with a high level of economic activity, and that the output UTXOs will be scattered. Some will belong to company customers who have withdrawn their bitcoins to self-custody wallets. Others may go to partner companies. Finally, there will undoubtedly be some exchange that will go back to the issuing company.

Exercise 3:

The model for this transaction is simple payment. We can therefore apply internal heuristics to the transaction to try to identify the exchange.

I have personally identified at least two internal heuristics that support the same hypothesis:

- The reuse of the same type of script ;

- The largest output.

The most obvious heuristic is that of reusing the same type of script.

Indeed, output 0 is a P2SH, recognizable by its

reception address starting with 3 :

3Lcdauq6eqCWwQ3UzgNb4cu9bs88sz3mKD

While output 1 is a P2WPKH, identifiable by its

address starting with bc1q :

bc1qya6sw6sta0mfr698n9jpd3j3nrkltdtwvelywa

The UTXO used as input for this transaction also uses a P2WPKH script:

bc1qyfuytw8pcvg5vx37kkgwjspg73rpt56l5mx89k

Thus, we can assume that output 0 corresponds to a payment and

output 1 is the transaction exchange, which would mean that the

input user always owns output 1.

To support or refute this hypothesis, we can look for other heuristics that either confirm our thinking, or decrease the probability that our hypothesis is correct.

I've identified at least one other heuristic. It's the largest output

heuristic. Output 0 measures 123,689 sats, while

output 1 measures 505,839 sats. There is therefore

a significant difference between these two outputs. The largest output

heuristic suggests that the largest output is likely to be foreign exchange.

This heuristic further strengthens our initial hypothesis.

It therefore seems likely that the user who supplied the UTXO as input still

holds the 1 output, which seems to embody the transaction's exchange.

Exercise 4:

The model for this transaction is simple payment. We can therefore apply internal heuristics to the transaction to try to identify the exchange.

I have personally identified at least two internal heuristics that support the same hypothesis:

- The reuse of the same type of script ;

- The round post output.

The most obvious heuristic is that of reusing the same type of script.

Indeed, output 0 is a P2SH, recognizable by its

reception address starting with 3 :

3FSH5Mnq6S5FyQoKR9Yjakk3X4KCGxeaD4

While output 1 is a P2WPKH, identifiable by its

address starting with bc1q :

bc1qvdywdcfsyavt4v8uxmmrdt6meu4vgeg439n7sg

The UTXO used as input for this transaction also uses a P2WPKH script:

bc1qku3f2y294h3ks5eusv63dslcua2xnlzxx0k6kp

Thus, we can assume that output 0 corresponds to a payment and

output 1 is the transaction exchange, which would mean that the

input user always owns output 1.

To support or refute this hypothesis, we can look for other heuristics that either confirm our thinking, or decrease the probability that our hypothesis is correct.

I've identified at least one other heuristic. It's the round amount output.

Output 0 measures 70,000 sats, while output 1 measures 22,962 sats. We therefore have a perfectly round

output in the BTC unit of account. The round output heuristic suggests that

the UTXO with a round amount is most likely that of payment, and that by

elimination, the other represents exchange. This heuristic further

strengthens our initial hypothesis.

However, in this example, another heuristic could challenge our initial

hypothesis. Indeed, output 0 is greater than output 1. Based on the heuristic that the largest output is generally

foreign exchange, we could deduce that output 0 is foreign exchange.

However, this counter-hypothesis seems implausible, as the other two heuristics

appear substantially more convincing than the largest output heuristic. Consequently,

it seems reasonable to maintain our initial hypothesis despite this apparent

contradiction.

It therefore seems likely that the user who supplied the UTXO as input still

holds the 1 output, which seems to embody the transaction's exchange.

Exercise 5:

We can see that 8 transactions can be associated with Loïc's identity. Of these, 4 involve the receipt of bitcoins:

2d9575553c99578268ffba49a1b2adc3b85a29926728bd0280703a04d051eace

8b70bd322e6118b8a002dbdb731d16b59c4a729c2379af376ae230cf8cdde0dd

d5864ea93e7a8db9d3fb113651d2131567e284e868021e114a67c3f5fb616ac4

bc4dcf2200c88ac1f976b8c9018ce70f9007e949435841fc5681fd33308dd762

The other 4 concern bitcoin shipments:

8b52fe3c2cf8bef60828399d1c776c0e9e99e7aaeeff721fff70f4b68145d540

c12499e9a865b9e920012e39b4b9867ea821e44c047d022ebb5c9113f2910ed6

a6dbebebca119af3d05c0196b76f80fdbf78f20368ebef1b7fd3476d0814517d

3aeb7ce02c35eaecccc0a97a771d92c3e65e86bedff42a8185edd12ce89d89cc

Exercise 6:

If we look at the model of this transaction, it's clear that it's a bundled expenditure. Indeed, the transaction has a single input and 51 outputs, indicating a high level of economic activity. We can therefore hypothesize that Loïc has withdrawn bitcoins from an exchange platform.

Several factors reinforce this hypothesis. Firstly, the type of script used to secure the UTXO input is a P2SH 2/3 multisig script, which indicates an advanced level of security typical of exchange platforms:

OP_PUSHNUM_2

OP_PUSHBYTES_33 03eae02975918af86577e1d8a257773118fd6ceaf43f1a543a4a04a410e9af4a59

OP_PUSHBYTES_33 03ba37b6c04aaf7099edc389e22eeb5eae643ce0ab89ac5afa4fb934f575f24b4e

OP_PUSHBYTES_33 03d95ef2dc0749859929f3ed4aa5668c7a95baa47133d3abec25896411321d2d2d

OP_PUSHNUM_3

OP_CHECKMULTISIG

What's more, the address studied 3PUv9tQMSDCEPSMsYSopA5wDW86pwRFbNF is reused in over 220,000 different transactions, which is often characteristic

of exchange platforms, generally unconcerned about their confidentiality.

The temporal heuristic applied to this address also shows a regular broadcast of transactions almost daily over a 3-month period, with extended hours over 24 hours, suggesting the continuous activity of an exchange platform.

Finally, the volumes handled by this entity are colossal. The address received and sent 44 BTC in 222,262 transactions between December 2022 and March 2023. These large volumes further confirm the likely nature of an exchange platform's activity.

Exercise 7:

By analyzing the transaction confirmation times, the following UTC times can be identified:

05:43

20:51

18:12

17:16

04:28

23:38

07:45

21:55

An analysis of these schedules shows that UTC-7 and UTC-8 are consistent with a range of current human activity (between 08:00 and 23:00) for the majority of schedules:

05:43 UTC > 22:43 UTC-7

20:51 UTC > 13:51 UTC-7

18:12 UTC > 11:12 UTC-7

17:16 UTC > 10:16 UTC-7

04:28 UTC > 21:28 UTC-7

23:38 UTC > 16:38 UTC-7

07:45 UTC > 00:45 UTC-7

21:55 UTC > 14:55 UTC-7

05:43 UTC > 21:43 UTC-8

20:51 UTC > 12:51 UTC-8

18:12 UTC > 10:12 UTC-8

17:16 UTC > 09:16 UTC-8

04:28 UTC > 20:28 UTC-8

23:38 UTC > 15:38 UTC-8

07:45 UTC > 23:45 UTC-8

21:55 UTC > 13:55 UTC-8

The UTC-7 time zone is particularly relevant in summer, as it includes states and regions such as :

- California (with cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, and San Diego);

- Nevada (with Las Vegas) ;

- Oregon (with Portland) ;

- Washington (with Seattle) ;

- The Canadian region of British Columbia (with cities like Vancouver and Victoria).

This information suggests that Loïc is likely to reside on the west coast of the United States or Canada.

Exercise 8:

Analysis of this transaction reveals 5 inputs and a single output, suggesting consolidation. Applying the CIOH heuristic, we can assume that all the input UTXOs are owned by a single entity, and that the output UTXO also belongs to this entity. It seems that the user chose to group together several UTXOs he owned, to form a single UTXO in output, with the aim of consolidating his parts. This move was probably motivated by a desire to take advantage of the low transaction costs of the time, in order to reduce future costs.

To write this part 3 on chain analysis, I drew on the following resources:

- The series of four articles entitled: Understanding Bitcoin Privacy with OXT, produced by Samourai Wallet in 2021 ;*

- The various reports from OXT Research, as well as their free blockchain analysis tool (no longer available for the moment following the arrest of the founders of Samourai Wallet) ;*

- More broadly, my knowledge comes from various tweets and content from @LaurentMT and @ErgoBTC ;*

- The Space Kek #19 in which I participated in the company of @louneskmt, @TheoPantamis, @Sosthene___ and @LaurentMT.*

I'd like to thank their authors, developers and producers. Thanks also to the proofreaders who meticulously corrected the article on which this part 3 is based, and gave me their expert advice :

Mastering best practices to protect your privacy

Address reuse

Having studied the techniques that can break your confidentiality on Bitcoin, in this third part we'll now look at the best practices to adopt to protect yourself. The aim of this part is not to explore methods of improving confidentiality, a subject which will be dealt with later, but rather to understand how to interact correctly with Bitcoin to retain the confidentiality it naturally offers, without resorting to additional techniques.

Obviously, to begin this third part, we're going to talk about address reuse. This phenomenon is the main threat to user confidentiality. This chapter is surely the most important of the entire course.

What's a receiving address?

A Bitcoin receiving address is a string or identifier used to receive bitcoins on a wallet.

Technically, a Bitcoin receiving address does not "receive" bitcoins in the literal sense, but rather serves to define the conditions under which bitcoins can be spent. In concrete terms, when a payment is sent to you, the sender's transaction creates a new UTXO for you as an output from the UTXOs it has consumed as inputs. On this output, it affixes a script defining how this UTXO can be spent at a later date. This script is known as "ScriptPubKey" or "Locking Script". Your receiving address, or more precisely its payload, is integrated into this script. In layman's terms, this script basically states:

"To spend this new UTXO, you must provide a digital signature using the private key associated with this receiving address."

Bitcoin addresses come in different types, depending on the scripting model

used. The first models, known as "Legacy*", include the P2PKH (Pay-to-PubKey-Hash) and P2SH (Pay-to-Script-Hash) addresses. P2PKH addresses always begin with 1, and P2SH

with 3. Although still secure, these formats are now obsolete,

as they entail higher transaction costs and offer less confidentiality than

the new standards.

SegWit V0 (P2WPKH and P2WSH) and Taproot / SegWit

V1 (P2TR) addresses represent modern formats. SegWit addresses

start with bc1q and Taproot addresses, introduced in 2021,

start with bc1p.

For example, here is a Taproot reception address:

bc1ps5gd2ys8kllz9alpmcwxqegn7kl3elrpnnlegwkm3xpq2h8da07spxwtf5

How the ScriptPubKey is constructed will depend on the standard you are using:

| ScriptPubKey | Script template

| ---------------- | ----------------------------------------------------------- |

| P2PKH | OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG

|

| P2SH | OP_HASH160 <scriptHash> OP_EQUAL |

| P2WPKH | 0 <pubKeyHash> |

| P2WSH | 0 <witnessScriptHash> |

| P2SH - P2WPKH | OP_HASH160 <redeemScriptHash> OP_EQUAL |

| P2SH - P2WSH | OP_HASH160 <redeemScriptHash> OP_EQUAL |

| P2TR | 1 <pubKey> |

The construction of reception addresses also depends on the script model chosen:

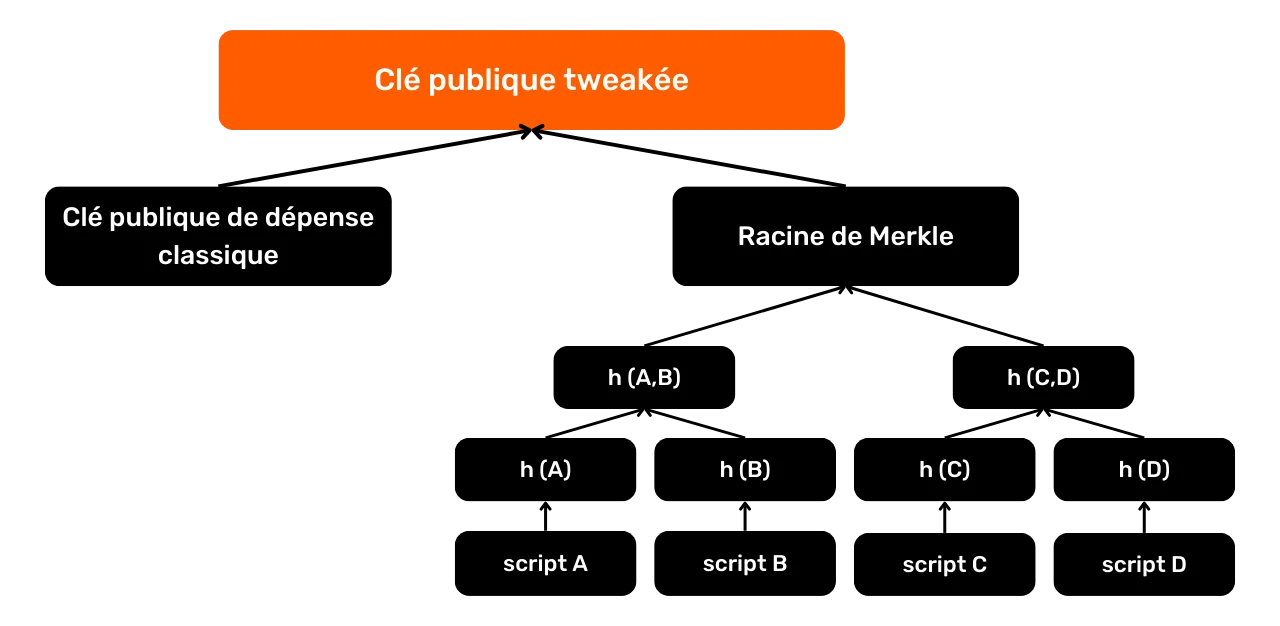

- For

P2PKHandP2WPKHaddresses, the payload, i.e. the core of the address, represents the hash of the public key; - For

P2SHandP2WSHaddresses, the payload represents the hash of a ; - As for

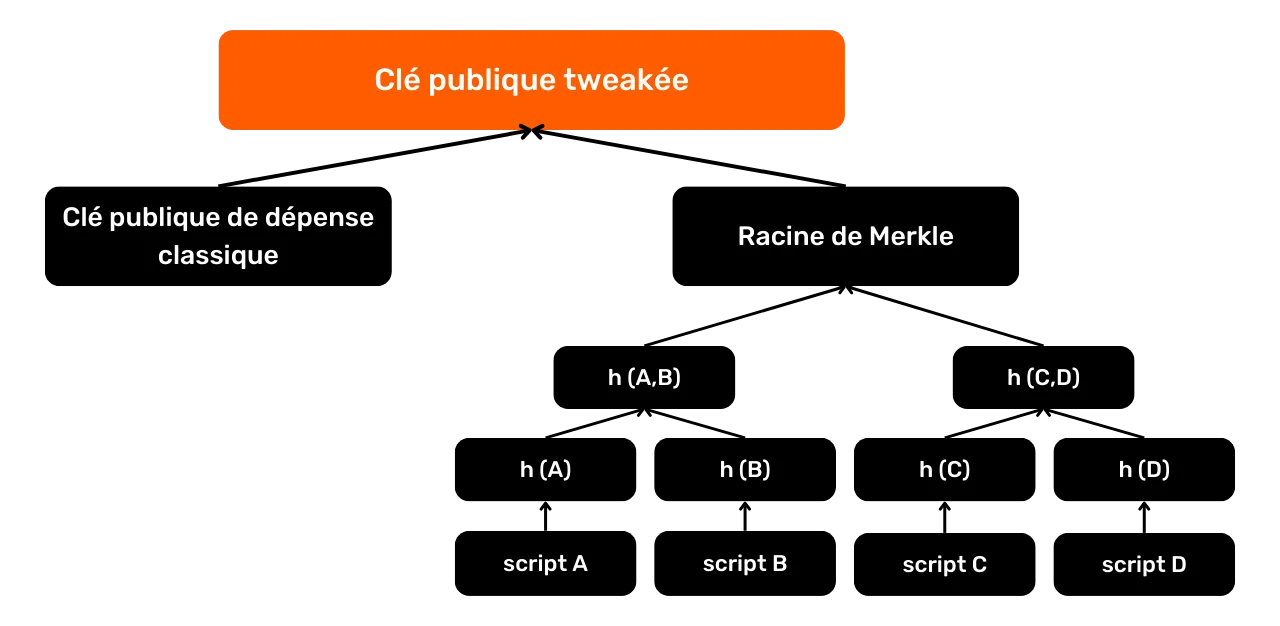

P2TRaddresses, the payload is a tweaked public key. P2TR outputs combine aspects of Pay-to-PubKey and Pay-to-Script. The tweaked public key is the result of adding a classic spending public key with a "tweak", derived from the Merkle root of a set of scripts that can also be used to spend bitcoins.

Addresses displayed on your portfolio software also include an HRP (Human-Readable Part), typically bc for post-SegWit addresses, a 1 separator, and a version number q for SegWit V0 and p for Taproot/SegWit V1. A checksum is also added to guarantee the

integrity and validity of the address during transmission.

Finally, the addresses are put into a standard format:

- Base58check for old Legacy addresses ;

- Bech32 for SegWit addresses ;

- Bech32m for Taproot addresses.

Here is the addition matrix for bech32 and bech32m formats (SegWit and Taproot) from base 10:

| + | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 0 | q | p | z | r | y | 9 | x | 8 |

| 8 | g | f | 2 | t | v | d | w | 0 |

| 16 | s | 3 | j | n | 5 | 4 | k | h |

| 24 | c | e | 6 | m | u | a | 7 | l |

What is address reuse?

Address reuse is the use of the same receiving address to block several different UTXOs.

As we saw in the previous section, each UTXO has its own ScriptPubKey, which locks it and must be satisfied for the UTXO to be consumed as input in a new transaction. It is within this ScriptPubKey that payload addresses are integrated.

When different ScriptPubKeys contain the same receiving address, this is called address reuse. In practice, this means that a user has repeatedly provided the same address to senders in order to receive bitcoins via multiple payments. And it's precisely this practice that is disastrous for your privacy.

Why is address reuse a problem?

Since the blockchain is public, it's easy to see which addresses lock which UTXO and how many bitcoins. If the same address is used for several transactions, it becomes possible to deduce that all the bitcoins associated with that address belong to the same person. This practice compromises user privacy by enabling deterministic links to be established between different transactions and bitcoins to be traced on the blockchain. Satoshi Nakamoto himself already highlighted this problem in Bitcoin's White Paper:

As an additional firewall, a new pair of keys could be used for each transaction to keep them unlinked to a common owner